28 Willie Bioff and Walt Disney

For a little man from Chicago, Willie Bioff held considerable power in Hollywood. By 1941 he controlled the workflow of thirty-five thousand people in the movie industry. Bioff could single-handedly order hundreds of studio employees to halt production or projectionists to stop playing that studio’s films. It was a two-pronged attack that threatened most Hollywood studios with bankruptcy. Sound technicians, camera operators, electricians, property men, teamsters, plasterers, utility workers, special effects technicians, and projectionists were all dues-paying members of the IATSE. As a wielder of unequaled power, Bioff had audience with the top brass of Hollywood.1

One of them was Joseph M. Schenck, the chairman of the board of 20th Century-Fox. Schenck, a long-faced man in his sixties, had been making deals with Bioff ever since the Chicagoan arrived as IATSE’s West Coast representative. That business relationship had been profitable for both. Bioff wouldn’t call a strike, and Schenck would thank Bioff with gifts to his personal bank account. It was a perfect arrangement.

Then in early 1941 Schenck was arrested for tax evasion. The movie mogul had tried to claim a loss when filing his taxes in 1935 and 1936. His trial began on March 3 and was to run several weeks. When the prosecutor, US attorney Mathias F. Correa, began exploring Schenck’s papers, he discovered something interesting—the extent of Schenck’s generosity to Bioff. There were enormous sums changing hands in 1936 and 1937, including a gift to Bioff of $22,000 in stock shares of 20th Century-Fox, and his $100,000 “alfalfa farm” loan. If Fox was just one of the major studios in Hollywood, then Bioff was earning far more than a labor leader’s $3,000-a-year salary.2

On around April 4 Correa started interrogating industry executives about their own gifts to Bioff. He discovered that the kickbacks were often in the form of cash (paid in $100, $500, and $1,000 bills) and dividends, but there were also Oriental rugs, draperies, furnishings, and other merchandise, as well as tens of thousands of stock shares. Some of the gifts were from known sources, like 20th Century-Fox and RKO, though many others were anonymous. On April 29, twelve days after winning his tax-fraud case against Schenck, Correa charged Bioff with tax fraud. Bioff had underreported $185,000 of earnings in 1936 and 1937 and owed $85,000 to the US government. It was the same charge that had landed Al Capone in prison years before. Now it looked like Bioff had followed in the footsteps of the big boss.3

The IATSE leader was arrested and placed on a $5,000 bail until his trial. Bioff’s court date was slated for July, but IATSE president George Browne was able to negotiate for a delay until September. It didn’t really matter to Correa; while on bail, Bioff couldn’t leave the state. For three more weeks Correa continued assembling a second, much larger case against Willie Bioff as well as against George Browne.

The news of that second case broke in the afternoon on Friday, May 23. Bioff and Browne were each indicted on charges of extortion and conspiracy. It was what Hollywood had been clamoring for. The story was so explosive that Variety, which had finished its morning print run for the week, rushed out a special edition that night. Willie Bioff and George Browne would have their day in New York federal court. A conviction could earn them each a thirty-year prison sentence. Bioff didn’t relent. “You can say for me that I am completely surprised,” he said. “I don’t know anything about the charges contained in the New York indictment. I never extorted a dime from anybody.”4

Correa put off the income tax trial indefinitely to bring Bioff and Browne to trial for extortion and conspiracy. He also arranged to conduct the prosecution personally. On May 27 in Chicago, George Browne surrendered to a US marshal. Smiling cheerfully, Browne told reporters, “I never committed a crime in my life.” The trial date was set for August 18 for both men.5

At his arraignment at New York federal court the morning of Thursday, June 12, Bioff was charged with collaborating with George Browne to extort $550,000 from Warner Bros., Paramount, Loew’s, and 20th Century-Fox. Bioff naturally pleaded not guilty. Correa voiced his fear of his own witnesses’ safety, and the judge agreed, warning Bioff, “I want it clearly understood that if any witnesses are molested in any form, either by telephone calls or personal communications, bail will be revoked forthwith and the defendant incarcerated.”6

Bioff explained to the press that the real reason for union corruption in Hollywood was “members of the Communist party.”7

Bioff was asked about gangsterism in the film unions, but he refused to answer. A reporter asked, “Is that all you want to say?”

Bioff barked, “That’s all!”8

On the night of June 13, Bioff flew back to California and returned to his ranch in the San Fernando Valley. He was there waiting on June 29 when Walt Disney arrived.

Immediately following Walt’s secret meeting in the Valley,9 the Disney strikers began seeing strange things. Anonymous lies were dropped to the press that the strike was already settled. SWEEPING VICTORY FOR CARTOONISTS IN STRIKE SETTLEMENT WITH DISNEY, read the Weekly Variety headline.10 Additionally, Walt Disney Productions released a notice that all strikers had to file an “application for reinstatement” within three days if they wanted to keep their jobs.11 This was on the heels of the Communism accusations made by the Committee of 21 against strike leader Herb Sorrell. The Disney strikers were shaken.

In the afternoon of Tuesday, July 1, nine guests arrived at Bioff’s mahogany-paneled mansion. Four were top Disney management, led by Roy Disney and Gunther Lessing. The other five were representatives from the American Federation of Labor (AFL), led by Aubrey Blair.12

In their alliance with Aubrey Blair and the AFL, the Disney strikers had overlooked one fact: George Browne, IATSE president (and Bioff’s partner), had been elected the vice president of the AFL.13 This demonstrated just how far the IATSE’s reach was.

Bioff’s home suggested sensitivity and culture, but mostly opulence. It was surrounded by alfalfa flowers and contained a knotty pine library filled with rare books. There were expensive Chinese vases and a kidney-shaped swimming pool. It was not the typical home of a professional union representative.14

Willie Bioff greeted his guests from Disney and the AFL, and together they drafted a proposal to end the Disney strike. Bioff always had the IATSE projectionists in his back pocket, and now was his chance to use them.

The Disney strikers were unaware of this AFL-Bioff-Disney negotiation. At the Screen Cartoonist Guild headquarters, Herb Sorrell, George Bodle, and the other strike leaders had prepared their own twenty-four-point proposal. These points included a pay scale with set increases, overtime pay, severance pay, a grievance committee, a screen-credit committee (Disney’s short cartoons were the only ones in Hollywood without screen credit), twelve days of sick leave, a union label on all Disney films, full retroactive pay for strikers, and a guarantee of fifty weeks of employment per year. Further was this stipulation: “Female employees shall receive equal pay for equal work and shall be accorded equal opportunity for advancement with male employees.”15 When Herb Sorrell read the terms, he received thunderous applause.16

At 6:30 that evening, Aubrey Blair and the other AFL leaders arrived at the Guild headquarters. The AFL offered the Guild a blanket agreement that would affiliate them with the IATSE. As an act of good faith, the AFL promised that Disney would sign a contract within twenty-four hours, or else all IATSE theater projectionists would stop running Disney films. But there was a catch: Herb Sorrell and George Bodle had to withdraw from negotiations. If they failed to agree, the AFL would sever its support for the Guild, the Painters Union with which it was affiliated, and the Disney strike.17

Sorrell had been loyal to the Guild, going so far as donating some of his salary to the Disney strike. Now, however, it looked like his presence was obstructing a possible settlement. For the sake of the strike, he said he would bow out. “If the IATSE had a method of settling it, it would be all right, and [I told them] that I would retire from the picture,” said Sorrell. “I only wanted to see them get what they had coming, and I did not want any part of it.”18 (Babbitt alone voiced a counterproposal: for the loyalists to be levied a 50 percent penalty on the salary they earned during the strike.19 Just like his epithets at the microphone, this would have denigrated the non-strikers.)

The strikers accepted Sorrell’s resignation and agreed to the terms of the contract. Babbitt and the other Guild negotiators rode in two of the AFL leaders’ cars to the signing location. All previous AFL meetings had been held at the Roosevelt Hotel, but the cars did not stop there, instead continuing toward the San Fernando Valley. The strikers inquired where they were going. Only then did the AFL leaders reveal that the contract would be signed at Willie Bioff’s ranch.

At the next opportunity, the Guild members in one car leaped from the vehicle and returned to Guild headquarters.20

The two Guild members in the other car did not bail. One of those two was Babbitt.21 Soon he found himself pulling up in front of Bioff’s mansion, where he saw Willie Bioff flanked by Gunther Lessing and Roy Disney.

Bioff had heard that Babbitt liked the outdoors, and he offered Babbitt his full salary if he were to stay out of the way, and “go camping” indefinitely.

Babbitt rejected the offer. He said he had enough money.22

Bioff grew furious. He demanded that Babbitt go along; otherwise Bioff would “take over” the Guild and the entire Disney studio.23

Babbitt didn’t budge.

With negotiations at a deadlock, Babbitt was driven back to the Guild headquarters.

That night the strikers held an emergency mass meeting. For the first time, strikers were pulled off the twenty-four-hour picket line. Sorrell chose to be absent. “I did not show up at the meeting that night, purposely,” said Sorrell, “and everyone wanted to know where I was. Aubrey Blair told them that I had got disgusted with the strike and that I was through.”24

There was considerable conflict and confusion as to why Bioff was involved at all. Booing filled the room. When it was time to vote on the AFL-Bioff proposition, the strikers unanimously rejected it. They voted “not to enter into any agreement to which Bioff was a party.”25

Roy Disney, Gunther Lessing, and chief engineer Bill Garity drafted an open letter to be published over Walt’s name, and placed a full-page ad in Variety on July 1:26

To My Employees on Strike:

I believe you are entitled to know why you are not working today. I offered your leaders the following terms:

(1) All employees to be reinstated to former positions

(2) No discrimination

(3) Recognition of your Union

(4) Closed Shop

(5) 50% retroactive pay for the time on strike—something without precedent in the American labor movement

(6) Increase in wages to make yours the highest salary scale in the cartoon industry

(7) Two weeks’ vacation with pay

I believe that you have been misled and misinformed about the real issues underlying the strike at the studio. I am positively convinced that Communistic agitation, leadership, and activities have brought about this strike, and has persuaded you to reject this fair and equitable settlement.

I address you in this manner because I have no other means of reaching you.

WALT DISNEY27

The next day, Variety printed another full-page ad with key words in bold:

Dear Walt:

Willie Bioff is not our leader.

Present your terms to our elected leaders, so that they may be submitted to us and there should be no difficulty in quickly settling our differences.

Your Striking Employees.28

Inside the studio, Roy Disney and Gunther Lessing called a company-wide meeting, informing the staff that the Guild rejected their offer. Lessing emphatically blamed the Guild, saying, “Every time we think there is a chance of a settlement they come back with outlandish proposals to upset everything. . . . They’re just using this Bioff stuff as a stall and an excuse.”29

Some strikers traveled to Herb Sorrell’s home. They wanted his help in fighting Bioff, and they hoped to woo Sorrell back to the strike. In doing so, they would risk losing the AFL’s valuable support not only for Sorrell but also for the Painters Union and the Guild. Sorrell agreed to rejoin the strike.30

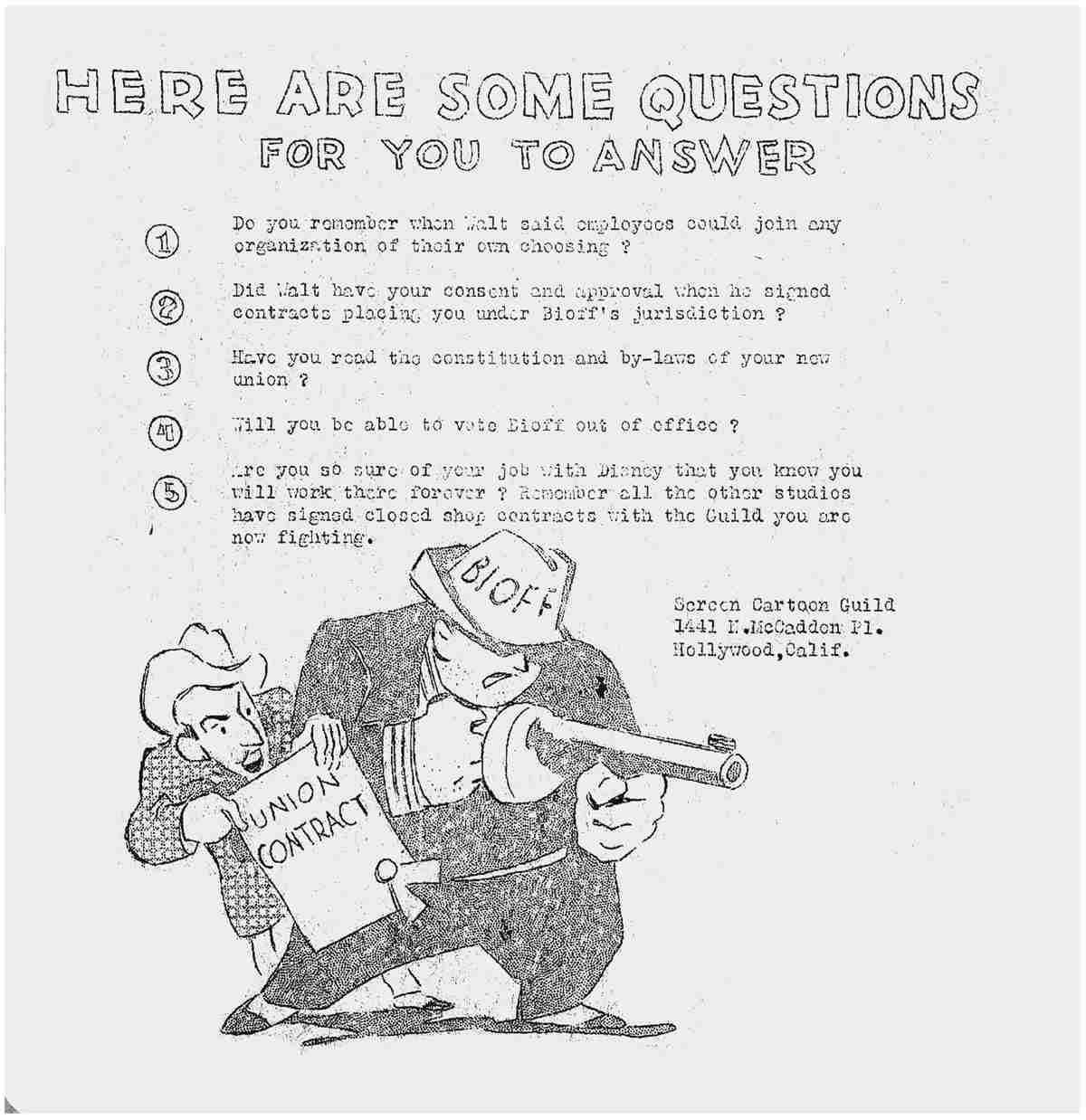

The strikers had facts to set straight and distributed handbills of Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse emphatically stating, “Disney Artists Still on Strike Despite Rumors” and “The Boycott is Still On!” As loyalists entered the front gates, the strikers handed out flyers that asked, “Do you know about the ‘negotiation’ meeting for which Walt and his new ‘chum’ waited in vain last night? . . . Bioff is our common enemy!” The strikers had an updated slogan: “Walt Cannot BIOFF Us!”31

A Disney strike flyer from July 11, 1941, caricaturing Walt and Willie Bioff.

Bill Littlejohn released a statement from the Screen Cartoonists Guild: “The strikers were never offered the terms advertised in the papers by Disney. Apparently the terms had been discussed only by Disney and Bioff.”32 The company revoked the closed-shop offer it had made. “We’re going ahead and make cartoon comedies without the strikers,” Lessing said. “Whenever we have met the union demands they have made new ones until the thing is ridiculous.”33 However, this did not mean that Bioff was completely out of the picture.

The strikers sought support from all allies. To the Teamsters’ Local 683, the Guild distributed a flyer stating, “If Bioff reestablishes his hold on motion picture labor it is the end of democracy, of honesty, and of decency in our trade union.”34 Notices of support began pouring in. AFL-affiliated unions nationwide continued to honor the Disney boycott. The Screen Actors Guild derided the Disney-Bioff alliance and donated $1,000. Even the Milk Drivers and Dairy Employees donated $250.35 When news of Disney’s collaboration with Bioff reached New York, clergy from Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish faiths wrote letters in protest.36

Bioff used the situation to petition for a delay in his prosecution. For his part in the Disney labor dispute, he was (as his lawyer called him) an “indispensable man.”37

On the evening of Friday, July 4, crowds gathered in front of Hollywood’s Pantages Theater and RKO Hillstreet Theatre for Hollywood’s first screening of The Reluctant Dragon.38 These additional screenings would bring in desperately needed revenue while helping with the studio’s public image.

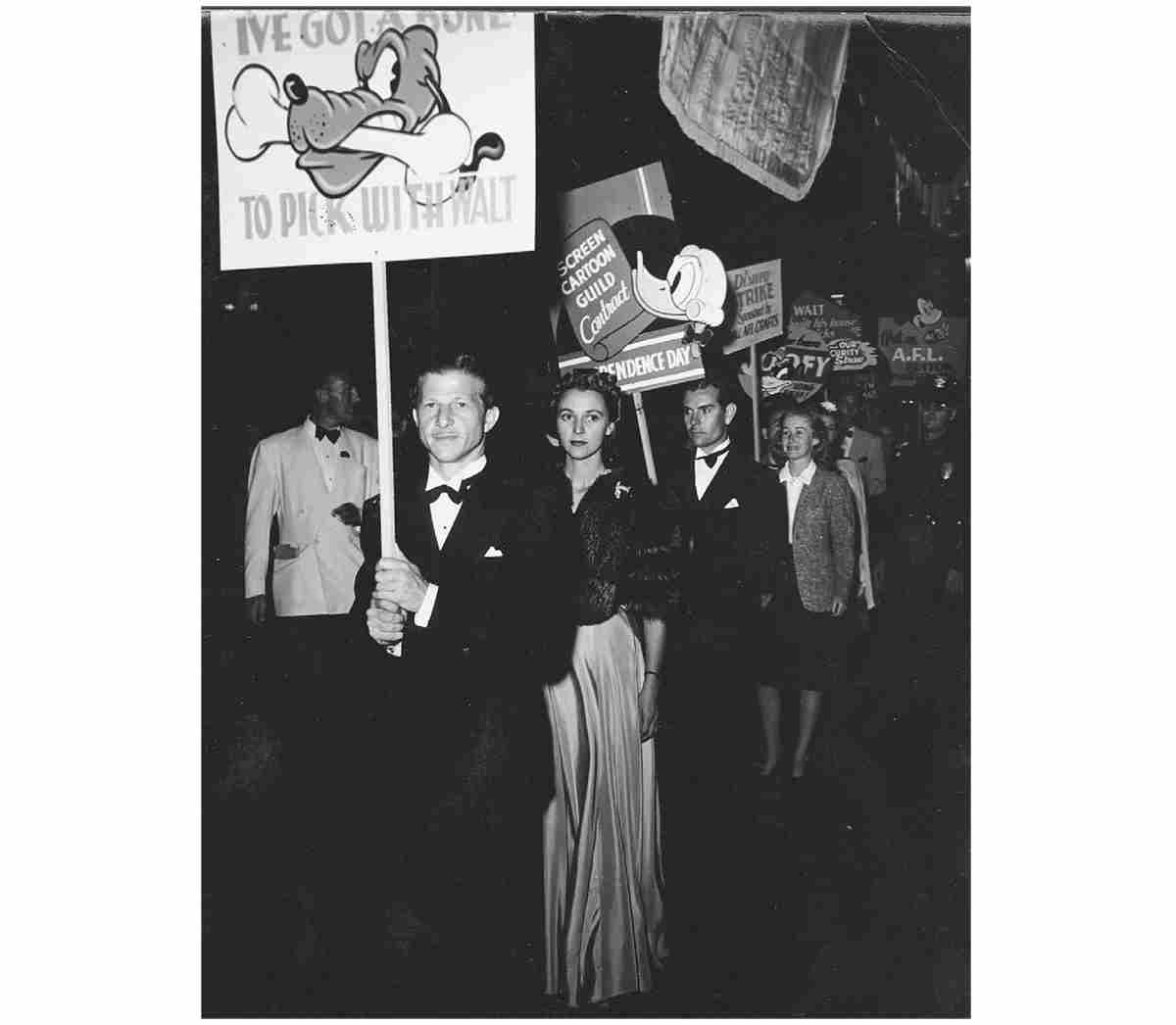

Soon chauffeured vehicles pulled up. A car stopped in front of the crowded theaters’ entrances, and out stepped Disney artists in formal eveningwear. Casually, the artists reached into the cars and pulled out their picket signs.

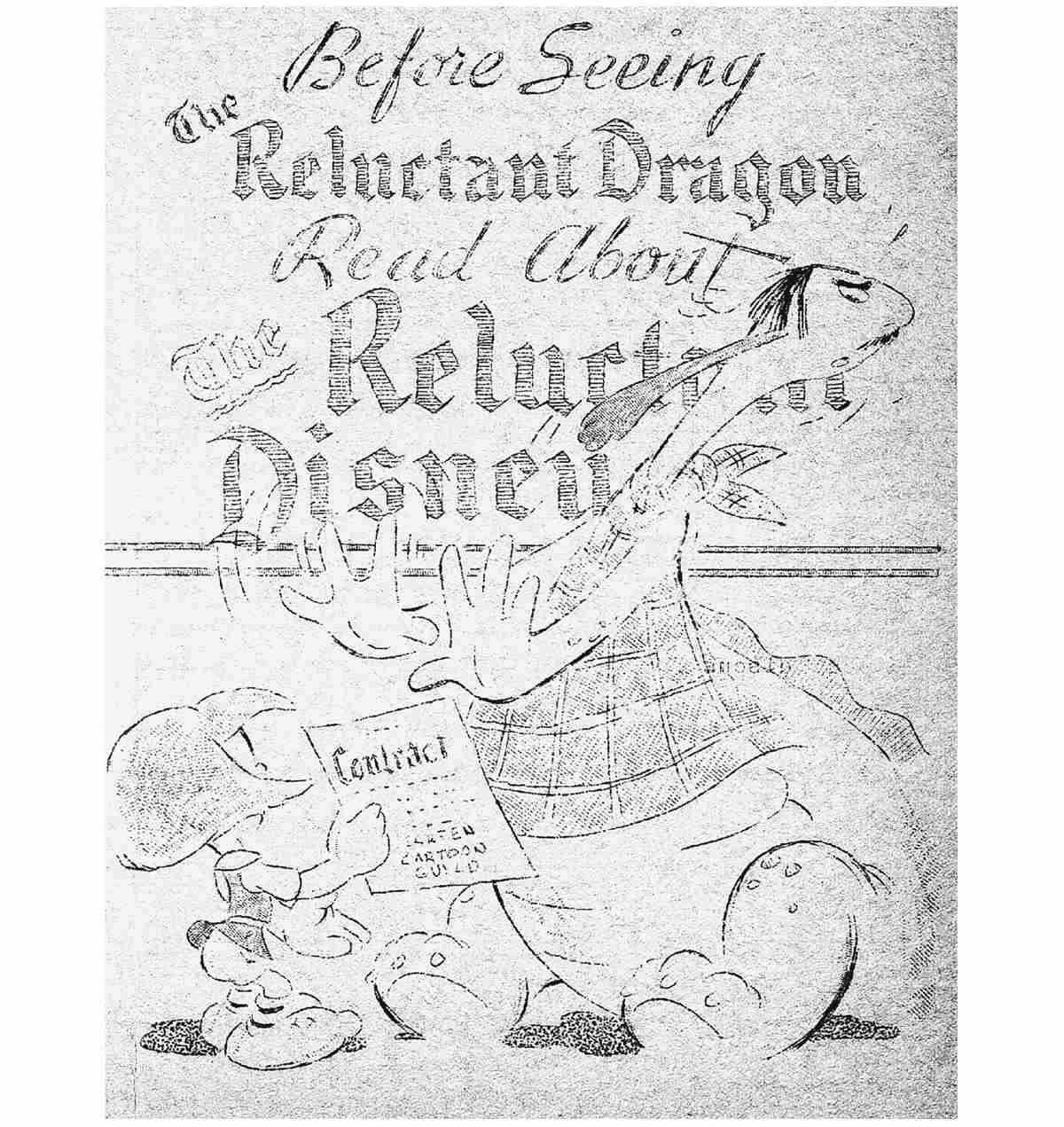

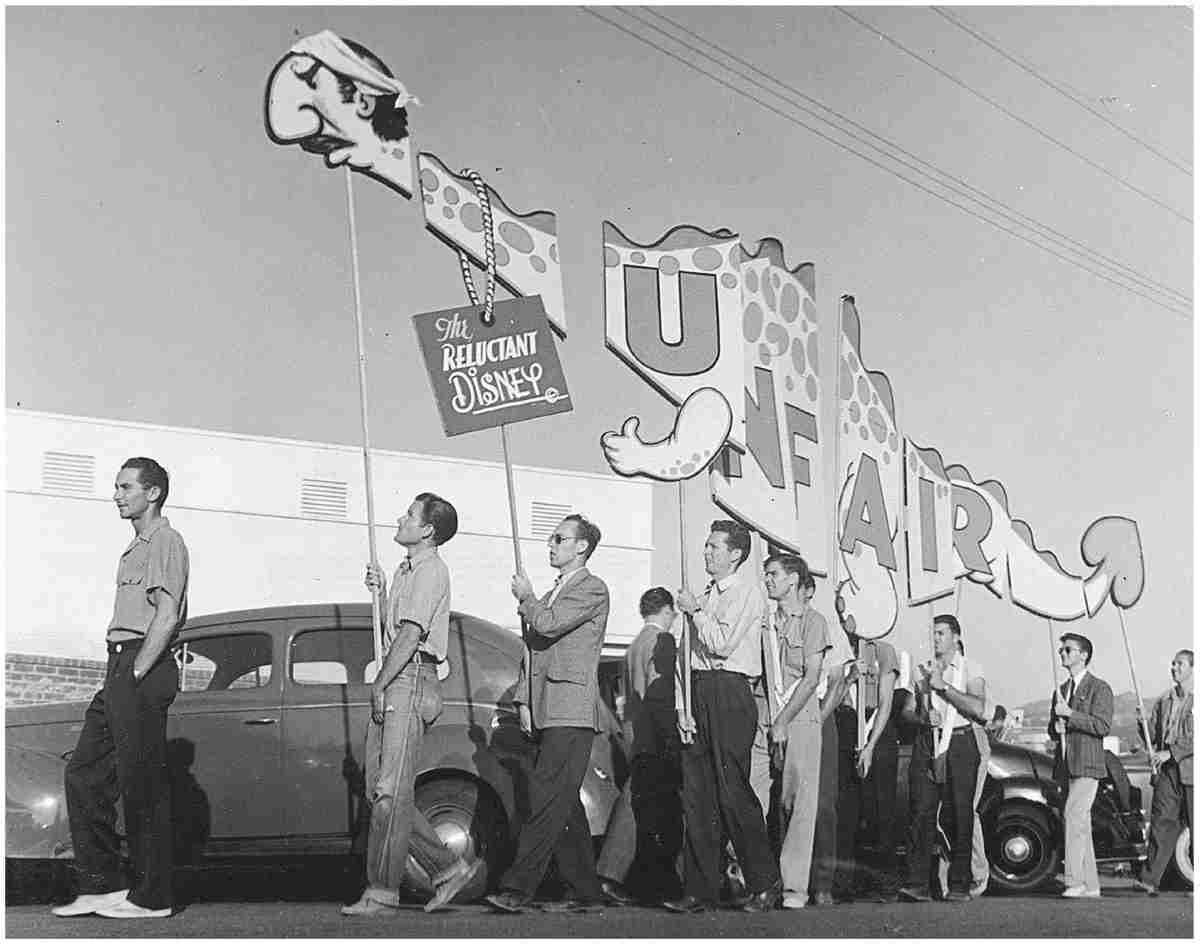

Disney strikers masquerading as chauffeurs continued to drop off other strikers dressed for a gala premiere. Picket signs with familiar Disney characters graced the air—along with new signs shaped like the Reluctant Dragon. The most elaborate sign constituted ten separate segments, requiring that many strikers to march in queue. It depicted an enormous dragon with the word UNFAIR across its side and Walt’s caricatured head bearing the label THE RELUCTANT DISNEY. One striker impersonated a radio emcee and interviewed the picketers with a microphone.39 Strikers handed newly mimeographed leaflets with illustrations of a Walt-dragon refusing to sign a union contract. “Walt is still the RELUCTANT DISNEY!!!”40

The Los Angeles premiere of The Reluctant Dragon at the RKO Hillstreet Theatre and its black-tie picket led by Babbitt, photographed by striker Kosti Ruohomaa, July 4, 1941.

The reviews were also colored by the strike. Box Office Digest called The Reluctant Dragon an industrial film “to sell the stockholders.”41 A half-page review in the Weekly Variety embedded this op-ed: “A curious coincidence is the relapse of ‘The Reluctant Dragon’—planned two to three years ago—at this particular time, when Disney’s studio employees are on strike. Dr. Goebbels couldn’t do a better propaganda job to show the workers in Disney’s pen-and-ink factory a happy and contented lot doing their daily chores midst idyllic surroundings.”42

The cover of a four-page leaflet distributed at theaters playing The Reluctant Dragon.

Support for the strikers’ anti-Bioff position rolled in like a tidal wave. At the start of the following week, Babbitt addressed the strikers: “I would say that our chances of winning are 100% because we have never been more solid!”43

Pickets continued with doubled fervor. Strikers marched outside the Carthay Circle Theatre, where Fantasia continued its record-breaking run, and outside the two theaters showing The Reluctant Dragon. The women of the strike arranged a phone-calling campaign to Disney’s switchboard and to theaters showing The Reluctant Dragon. “Keep their lines busy all the time,” they wrote. “Ask your friends to help you do just that.44”

Herb Sorrell remembered that the Disney company took drastic measures. “Mr. Disney, when he could not get any police from the city, decided to hire fifty private police from outside the city,” he said. “We almost came to blows there.”45 With the help of Burbank police, Sorrell had the private officers confined inside the property line.46

Bioff’s goons arrived, unmistakable in flashy clothes and torpedo-style cars, threatening the speaker at the strikers’ microphone. A non-striker who saw this wrote “that anyone who tries to fight those [IATSE] leaders is risking his job and perhaps his life.”47

It was an uncomfortable situation for all parties. Bioff had his fingers in Walt Disney Productions; now he tried to dictate to Walt the terms of a contract with Disney employees. He used his signature ploy: threatening to stop all IATSE projectionists from playing Disney films. Artists on strike was one thing, but even his non-strikers knew that without projectionists, “Walt is helpless.”48

At that time, Walt tried to reason why he enlisted Bioff: “Believe me, he honestly tried to settle the thing peacefully. All he got out of it was a kick in the chin and I’m telling you the deal was not a bargain for me.”49

Then the colossus swooped in. Some strikers had reached out to the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), the AFL’s rival. The CIO had dominated the industrial unions of the Midwest but aspired to expand into entertainment crafts as well, and offered to back the Screen Cartoonists Guild both financially and morally.

Herb Sorrell politely turned down the CIO. For now, the strikers were still part of the AFL.50

Clearly, Sorrell and the Guild were certain that Disney and the AFL would come to their senses and abandon Willie Bioff. That thought was soon dashed. On Tuesday, July 8, Bioff was spotted entering the building where the AFL’s western director had an office. Shortly afterward, Roy Disney, Gunther Lessing, and Bill Garity also entered, followed by AFL representative Aubrey Blair, the IATSE’s international representative, and heads of eight local unions under the IATSE’s control. These unions—the Teamsters, the Soundmen, the Electrical Workers, the Plasterers, the Laboratory Workers, the Utility Workers, the Projectionists, and the Cameramen—had all honored the Disney strike for six solid weeks.51 Their involvement accounted for ninety-eight souls on the picket line, according to the studio.52 (The Guild counted twenty-one.)53

By the time the meeting was over, each of these eight local unions had been ordered to sign blanket contracts and return to work. As reported by the press, the IATSE’s pretense for this act was “cleaning out Commies and curb any CIO muscle-in attempt.”54 The Disney camera operators would resume filming Disney animation, and the laboratory workers would begin processing one hundred additional Technicolor prints of The Reluctant Dragon.55 In a final blow to the Guild, the AFL called off the Disney boycott.56 No longer would the AFL support the Disney unit of the Screen Cartoonists Guild.

The Disney strikers were in a panic. They feared that the IATSE might now issue a charter for their own cartoonists’ union. The irony was head-spinning: the very purpose of forming an independent cartoonists’ union had been to block Bioff at Disney, and now it appeared that Disney would use Bioff to block them—the independent union!

The Guild meeting that evening continued well past midnight. Sorrell and the leaders explained that this was a single hang-up and they expressed unwavering confidence in their eventual triumph. After all, the Guild still had Disney’s twenty-six striking film editors on their side.57

The next day, Wednesday, July 9, the IATSE ordered the film editors back to work. Filing past the pickets on Thursday, the editors apologized to the striking cartoonists.58

“The defection of certain Bioff-dominated unions did not change the situation,” announced Bill Littlejohn.59 “The demands of the union are the same as they were six months ago. We have never had an opportunity to present our proposals to Walt because he, in violation of the Wagner Act, has consistently refused to meet with his employees. Apparently Walt prefers to deal with Willie Bioff.”60

The National Labor Relations Act (or Wagner Act) listed five unfair labor practices. The Disney company had already been charged with three: coercing employees, dominating the formation of a labor organization, and discrimination in regard to tenure of employment. Now attorney George Bodle charged the company with a fourth: refusing to bargain collectively with the employees’ representative.61

While Roy Disney and Gunther Lessing were facilitating this defection, Walt was at a particular standstill. The US Office of Inter-American Affairs was prepared to bankroll Disney for its research trip to Latin America. This was part of the government’s “Good Neighbor” program to combat the spread of Naziism in the Americas. It was a remarkably fortuitous deal. The group’s arrival in Argentina was originally planned to coincide with Fantasia’s premiere in Buenos Aires, but the strike had delayed that. The federal government refused to move forward with the plan while the strike remained unsettled.

Desperately, Walt called a local government agent, US labor arbitrator Stanley White, to see if he could settle the strike.62 “The government wanted me to go to South America,” said Walt in 1942. “That is why we agreed to arbitration.”63

As opposed to conciliation or mediation, arbitration would decide once and for all. Washington quickly dispatched White to the Disney studio. Walt was ready for the US government to settle it.

The Disney strikers carrying their ten-segmented RELUCTANT DISNEY sign, photographed by striker Kosti Ruohomaa.