17 The Norconian

Work resumed at the Disney studio on Monday as usual, and Babbitt flipped his drawings of Goofy in the new Mickey-Donald-Goofy cartoon, The Whalers.1 He animated nearly every Goofy scene in that cartoon and, as usual, took up huge quantities of screen time. Now he liberally used live-action reference for Goofy, choreographing his movements before his pencil even touched the paper.

Babbitt was proud to have developed this technique, but he was the only animator who relied on it for the shorts. As the younger art-school graduates like Frank Thomas and Woolie Reitherman continued to climb up the studio ladder, Babbitt struggled to remain relevant.

He wasn’t the only one. Norm Ferguson, the Pluto specialist who had introduced personality animation to the Disney studio, sometimes found himself unable to draw without incredible effort.2 Fred Moore, the Mickey Mouse specialist who discovered squash-and-stretch, often found himself in a depressive rut, needing emphatic compliments or sometimes turning to alcohol.3 Bill Tytla, the most experienced fine artist of the cohort, became so sensitive that a slight critique on his drawing ability could crush him for “a week, maybe two.”4

Meanwhile, the younger animators seemed to glide effortlessly through their assignments. When Ferdinand the Bull5 went into production, puckish art-school graduate Ward Kimball handled the bullfighter scenes with impish delight. For the parade into the bullring, Kimball caricatured Disney animators as the banderilleros. Fred Moore’s caricature waddled in like a toddler. Tytla’s caricature (a picador) looked like a Cossack on a horse. Babbitt’s caricature marched in like a pugilist, jaw protruding and fists swinging.6

In life, Babbitt and Tytla were drifting apart. Bill and Adrienne married on April 21, 1938, and he chose Joe Grant as his best man. Grant had worked his way up since 1933 and now was head of the Character Model Department. Following the wedding, the Tytlas began making plans to move to La Crescenta, California.7

Babbitt’s closest friendship was disintegrating before his eyes.

The Snow White artists patiently awaited their profit-share bonuses as the film made huge returns all over the world. In May, Walt and Roy made enough money from Snow White to pay back their bank loans. For the first time in two years, the studio was out of debt.8 Walt immediately bought a new house in North Hollywood for his parents, Elias and Flora. Next, Walt would give his staff the greatest party they had ever seen.

On May 10 a new story outline appeared on the bulletin boards. It looked like all the other outlines for short cartoons still in the story phase. This “short” was called “Walt’s Field Day.” Beneath that was written, “Characters: Entire studio personnel and one guest per person. Locale: Lake Norconian Club. Time: June 4, 1938—from 10:00 AM on.”

The memo laid out plans for an adults-only day outdoors, followed by a dinner and dance. Eight Disney employees volunteered for the Field Day Committee to help organize the event, including Ward Kimball, Hal Adelquist, and Art Babbitt.9 It appeared to be the perfect time for Walt to announce the distribution of the Snow White bonuses to his employees.

Saturday, June 4, the Disney employees and their friends drove the ninety minutes to the luxurious Lake Norconian Club. It was furnished with fifteen badminton courts, fifteen Ping-Pong tables, twenty-five horses for riding, ten horseshoe pits, a lake for boating, a pool for swimming, and grounds to play all sorts of games. A handful of donkeys grazed in the fields.

All day there were organized competitions in golf, badminton, Ping-Pong, horseshoes, swimming, volleyball, baseball, touch football, foot races, and rowing, with trophies promised to the winners. Then came the cocktail hour, followed by a lavish dinner and dancing in the grand ballroom with a live orchestra. The Disney employees had booked the hotel rooms to capacity.

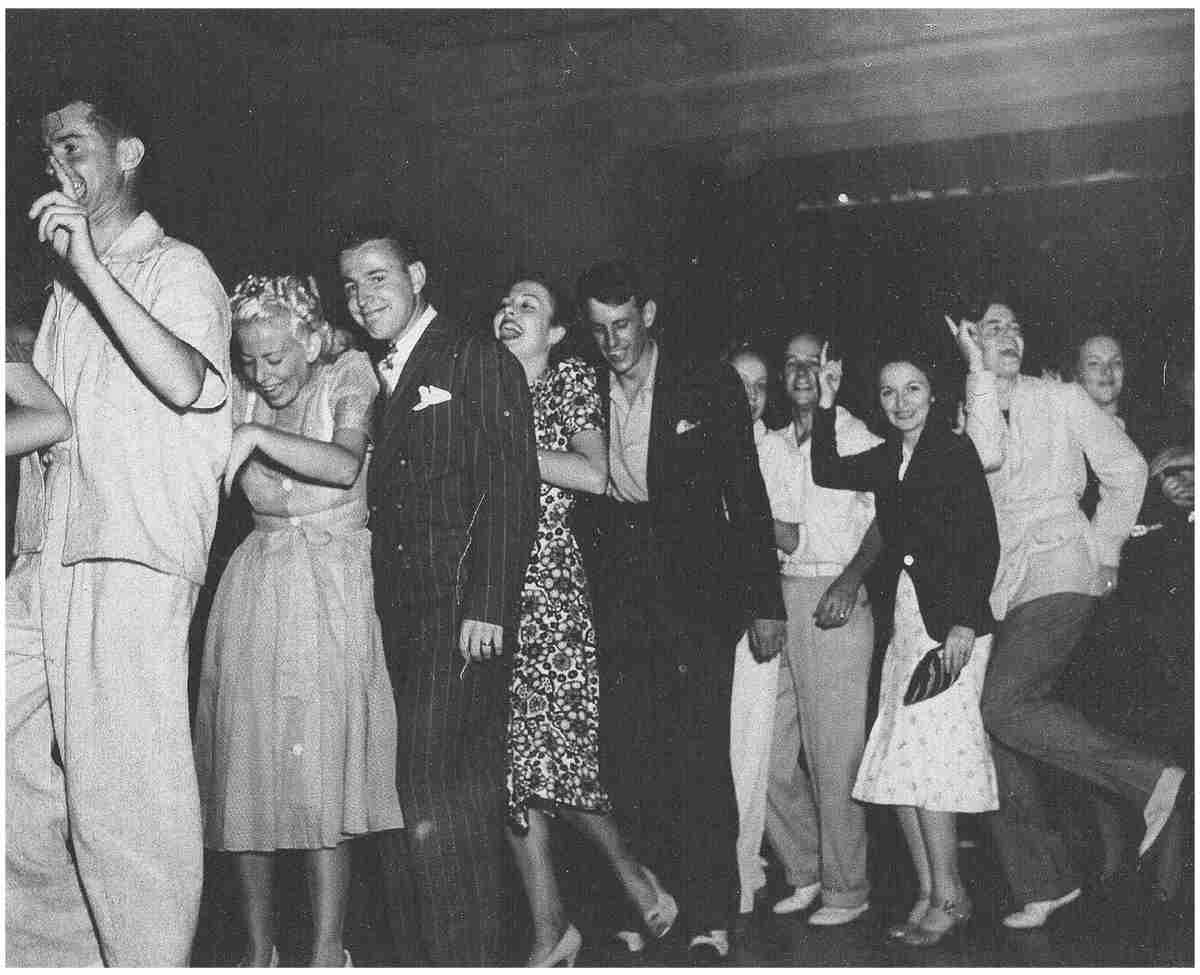

Party at the Norconian, June 4, 1938. Marge Babbitt is at center, in front of artist Willis Pyle.

At 11:30 that evening, the band paused as head story man Ted Sears took the stage. He announced the winners of the day’s events.10 There were cacophonous cheers. Then Walt himself took the stage—the moment that everyone had been waiting for. Those late hours and unpaid overtime on Snow White, the success of the film, all added up to those promised bonuses.

Walt began by outlining the company’s new direction toward feature films. He addressed the exciting new productions in the pipeline, including Bambi and Pinocchio. He said he hoped that this day would invigorate everyone for the work that lay before them. And with a closing pleasantry, he took his seat.11

There was confused, nervous applause. The live band resumed its set as scheduled. The Disney employees looked at one another, wondering where the bonuses were and if this party itself was the bonus. The room was now tainted with shattered expectations. The drinking increased. The tension grew. “For two years, all of us had been under terrible pressure, working long hours day and night to finish Snow White,” remembered one of Babbitt’s inbetweeners. “Something just snapped.”12

Someone rode one of the horses into the hotel lobby. Other drunken men and women climbed onto the field donkeys and tried to ride them. And still others began throwing each other into the pool, fully clothed.13

Soon, one artist recalled, “there were naked swim parties, people got drunk and were often surprised what room they were in and who they were sleeping next to when they awoke the next morning.”14 Another artist recalled couples swapping partners.15 Fred Moore drunkenly tumbled out of the hotel’s second story balcony onto a shrub, unscathed.16

Walt and Lillian Disney drove off, disgusted, leaving the wake of chaotic employees behind them. He never mentioned the party again, and in his presence, neither did they.

The talk about eventual bonuses did not die down, but there was work to be done. Pinocchio desperately needed an overhaul, and Art Babbitt, Bill Tytla, and Fred Moore were all called in to redesign Geppetto.

New voice actors were cast. German-born actor Christian Rub would play Geppetto. Babbitt listened to the recording of Rub’s voice—soft and kindly—and began sketching.

He realized the animators had been going about Geppetto all wrong. The character was not a crotchety hermit but a soft-hearted papa. Babbitt injected the warmth of Rub’s voice into his new designs, giving Geppetto a full head of hair, a mustache, and a leaner, bent frame. He submitted the designs, to the supervisors’ approval. Hal Adelquist, now the chief assistant to Pinocchio director Ben Sharpsteen,17 requested Babbitt lead a meeting on Geppetto’s redesign with the animation assistants.18

The changes in Babbitt’s design of Geppetto had one striking aspect: whether conscious or not, Babbitt had redesigned the character with the physical characteristics of his own father.

In July 1938 Dave Hand proposed an intricate new lecture program to Walt: the low-level artists would attend lectures by the mid-level artists, the mid-level artists would attend lectures by the top-level artists, and the top-level artists would be lectured by professional artists (including muralist Diego Rivera, writer Alexander Woollcott, and architect Frank Lloyd Wright.)19 In addition, a Development Board would be formed to give written critique of each Disney artist, thereby sharpening their specializations. Walt gave it his OK.20

During that year, one of the supervising directors on Pinocchio offered Babbitt a promotion—from supervising animator to sequence director.21 But Babbitt passed on the offer. He preferred doing his own animation with his assistants, not managing a cadre of others. Nonetheless, as a supervising animator (along with Tytla and Moore), he now shared the same rank as the younger art-school graduates like Frank Thomas and Woolie Reitherman.22

On June 28, 1938, the Los Angeles Examiner had announced that Walt Disney would distribute 20 percent of Snow White’s earnings to his eight hundred employees, each bonus representing about twelve weeks’ wages. The artists were ecstatic.23

By the end of the summer, the trade papers were reporting that Snow White had grossed $2 million,24 on the way to being the most successful film of its day. However, Roy Disney posted a curt memo on the bulletin boards discouraging taking the trade papers’ figures too seriously. “That was a tactical error,” recalled an animator, “because we all knew that, in this area at least, trade papers are fairly accurate.”25

Neither Roy Disney nor Gunther Lessing offered either a bonus delivery date or an amount. Word spread that the bonuses were never coming at all.26

Finally that summer the Snow White bonuses were distributed. Compared to the fat bonuses for the short cartoons, the Snow White bonuses were a pittance. Some of the artists received an amount equal to or smaller than they had received for the shorts. Some artists received none at all. “There was more confusion and hostility,” an artist recalled. Even Walt’s most loyal animators thought this was poorly managed.27

Babbitt earned no bonus for Snow White.28 Whatever formula that had earned Babbitt large bonuses on shorts was now gone, without explanation.

In late August, The Whalers was released, prominently featuring Babbitt’s Goofy animation. Babbitt received no bonus for that either.29

While the bonus fiasco flickered through the animation ranks, Walt was consumed with other, grander things. In his office, he and Roy held maps and construction plans, budgeting them against the company checkbook. Walt envisioned an animation campus, a streamlined plant specifically built for cartoon production—the only one of its kind in the world. On August 31, he and Roy put their first deposit down for a fifty-one-acre plot in Burbank. This would be the site of the new Disney studio.

By early September 1938 Pinocchio was back on track.30 Jiminy Cricket had just been added, and Pinocchio himself was reshaped to be much more likeable. The story was still an epic narrative, but the completed storyboards now fit Walt’s recipe for movie magic.

By the end of September, Walt was selecting music for a new feature film he was calling “The Concert Feature.” The idea for the Sorcerer’s Apprentice short had expanded the previous March into a pastiche of classical music–inspired animation. Famed conductor Leopold Stokowski would enthusiastically conduct the Philadelphia Orchestra to accompany the animation.31 Employees walking through the main building could hear the classical music played throughout the hallways as ideas were brainstormed and stories crafted.

The studio chose classical pieces that were rich with visual opportunity. Different ideas filled the pushpin boards for each musical number, including Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite. Eliminating the Christmas motif, story artists began interpreting the melodies through nature. Thistles and orchids would perform the Russian Dance, and lizards would perform the Chinese Dance while mushrooms acted as lamplighters. (The lizards would eventually be replaced by mushroom dancers.)32

The artists often had to halt their progress to attend an anti-union “information seminar” by Vice President Gunther Lessing. He repeatedly warned the staff about joining an independent union like the Screen Cartoon Guild. He said that the animation artists “on the outside” of Disney walls needed unions to protect them because they were untalented and lazy. Many of the Disney artists who heard this had once worked “on the outside” and still had friends in those studios. They also had no personal investment in Lessing, whose way of speaking was “too slick, too facile, and too arrogant.” To previously uninformed staff, these seminars began educating them about the Guild’s existence.33

The Guild was growing its numbers and succeeding in signing up animators where the IATSE had not. Bad press also weakened the IATSE—on September 7, Willie Bioff was charged with having accepted a bribe in 1936 from Joseph Schenck, the 20th Century-Fox mogul. Even at the time of the transaction, it had alarmed the public, not only because of its enormous sum of $100,000 but also because of the pretext—this was a loan toward an alfalfa farm.

The charge opened up an examination of all of Bioff’s business dealings going back to his 1936 arrival in Hollywood. A regional labor board director began to investigate. Bioff immediately retreated from his post as IATSE’s West Coast representative and relocated to New York, biding his time until things cooled down.34

Bioff’s self-imposed exile did not stop the IATSE from claiming to represent Disney employees, even while the Federation of Screen Cartoonists claimed them. On September 21, the National Labor Relations Board finally investigated the Federation’s petition for recognition and issued a legal hearing. Notices for the hearing were sent to all the unions that had ever staked a claim at Disney—the IATSE, the Federation, and the Screen Cartoon Guild.35

Lessing responded to the notice on behalf of the Disney company: He denied that the Federation—the group that he and Babbitt had formed—represented the majority of the employees, and therefore it could not be recognized. He argued that enforcing the National Labor Relations Act would deprive some Disney employees (i.e., management) certain civil rights. He asked that the petition be dismissed.

It was not. The National Labor Relations Board hearing took place on October 24. Lessing represented the Disney company, and Leonard Janofsky and Babbitt represented the Federation.36 Seven separate attorneys represented various local branches of the IATSE.37 The Screen Cartoon Guild did not attend, honoring its noncompetitive agreement with the Federation.

Of the 675 total employees at the company at that time, 602 of them worked in animation production. Janofsky produced the Federation’s 588 union membership cards.38

A final verdict would arrive in the months to come. Until that verdict, Lessing refused to recognize the Federation as the Disney studio’s union.

On October 25 Dave Hand submitted his final draft of the “Development Program Plan of Operation”; it would hold classes on subjects like Story Construction, Timing, Pantomime, Composition, and Caricature. There were three skill levels. Group A—the highest—had nine names, including Bill Tytla, Fred Moore, and Norm Ferguson, as well as younger art-school grads like Frank Thomas and Woolie Reitherman. Babbitt was placed in Group C.39

Management did not share Hand’s low opinion of Babbitt. On October 27 Babbitt’s contract was renewed at $200 a week, still among the highest-paid artists at the studio.40

In November,41 a nineteen-year-old named Bill Hurtz had just completed a year of training under Don Graham. He was thrust into Babbitt’s animation unit, and for $25 a week he worked as one of Babbitt’s animation assistants.42 Hurtz was terrified and a little starstruck. He remembered first seeing Three Little Pigs years ago in a local cinema and reading Babbitt’s name under the art displayed in the lobby.43

Walt Disney was increasingly dubbed a manufacturer of happily-ever-afters. He had revived the orphaned Snow White from her coffin and was currently bestowing Pinocchio the soul of a real boy. These make-believe children touched death. The theme of tragedy and redemption hung heavy in Walt’s heart, even before the events of Saturday, November 26, 1938.

The new house he had bought his parents was a death trap. The furnace had a gas leak and had been poisoning Flora and Elias Disney. They both collapsed at the house from asphyxiation. Walt’s father was barely alive when the ambulance arrived.

Walt’s mother, however, was already dead.

It was the worst event that Walt had ever experienced. The news was quietly passed to the staff who worked closest with Walt, which would have included Babbitt. Babbitt knew what it was like to lose a parent under tragically avoidable circumstances. His own father’s injury and premature death had hardened Babbitt against the travails he encountered in life.

Unfortunately, the same would prove to be true for Walt.