22 The Guild and Babbitt

BABBITT REFUSED TO PARTICIPATE any longer in the Federation, which was now campaigning to sign up as many Disney artists as possible. Bill Roberts, still acting as president, had prepared new blank membership cards.

Technically, Roberts himself was now a supervisor, ranking him among management and therefore ineligible to join a union. Nonetheless, studio supervisors soon appeared with stacks of Federation membership cards and handed them to the lower-level artists, including one of Babbitt’s assistants.1 This coercion was deliberately in violation of the National Labor Relations Act. If the Federation wouldn’t take labor law seriously, perhaps someone else would.

The Screen Cartoonists Guild got wind of these coercive tactics and soon sent orders to the studio to cease and desist. On the afternoon of January 4, 1941, Roberts had a secret meeting with a few of Walt’s most loyal supervising artists at one participant’s home. There was a Guild spy at the studio, he said, and the group debated who it could be. They suspected Norm Ferguson.2

On January 9 the Guild began its campaign to organize Disney. Sorrell and the AFL drafted flyers, printed at the AFL’s expense, and gave the flyers to newsboys hired to distribute them at the Disney gate.3 These papers answered questions like “How can I show an interest in the Guild without endangering my job?” and “If I have already signed a Federation card does that bind me to vote for it?” (It didn’t.) The flyers also emphasized how affiliation with the AFL strengthened the Guild. The handouts invited all Disney employees to an evening seminar on Thursday, January 16.4

The afternoon before that seminar, the Federation convened in the local high school auditorium. To everyone’s exasperation, nothing was accomplished, and no plans were laid out. “What a bunch of amateurs,” commented one artist.5

The Guild’s meeting included several speakers: AFL representative Aubrey Blair, Screen Cartoonists Guild attorney George Bodle, and Guild business manager Herb Sorrell, as well as representatives from the Screen Writers Guild and the Screen Office Employees Guild. By the end of the meeting, it was confirmed by the press that a “big majority” of Disney workers had signed up with the Guild.6

This did not sit well with Walt’s most loyal artists, including director Wilfred Jackson and a group of the art-school graduates, like Woolie Reitherman and Frank Thomas. They sought help from their boss, though Walt resisted. “I explained to them that it was none of my concern, that I had been cautioned to not even talk with any of my boys on labor,” Walt said in 1947. The delegation said that they did not want to follow Herb Sorrell, and they proposed a studio-wide election to vote for their preferred union.7

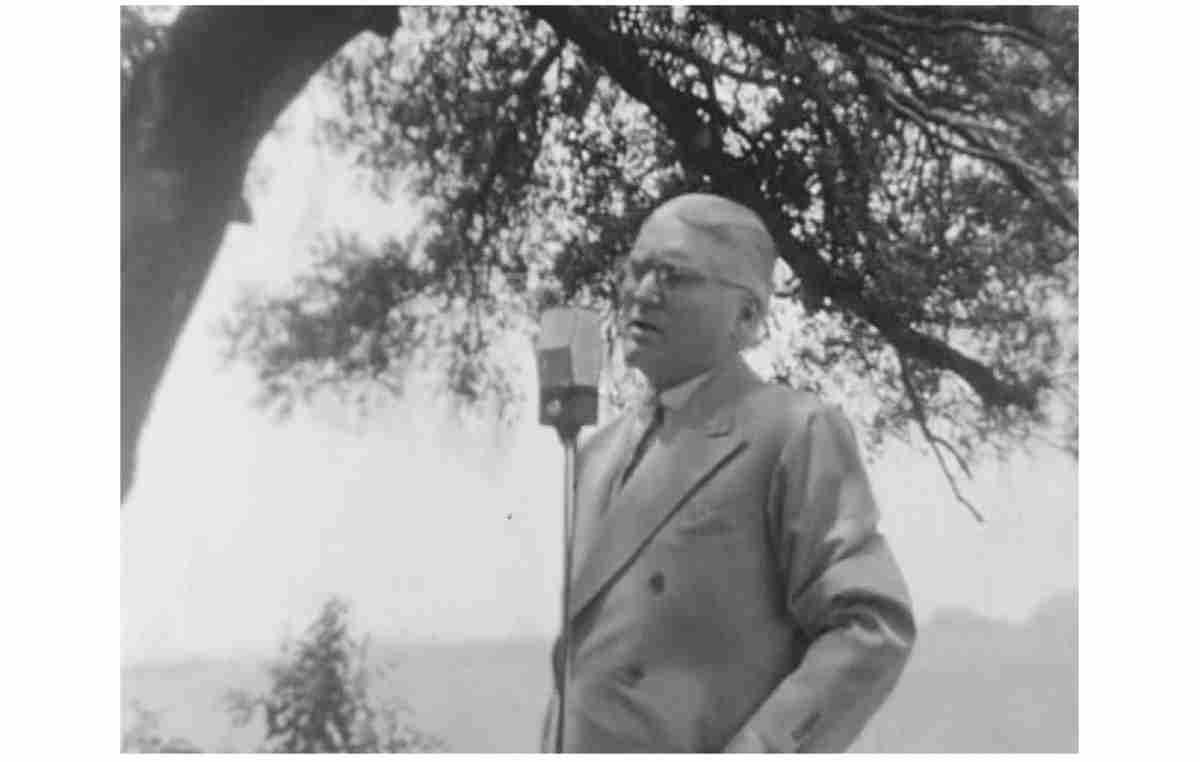

AFL representative Aubrey Blair. Image captured by striker Ray Patin.

An election, Walt concurred, would be a clear decider. The Guild agreed to this and filed a petition with the National Labor Relations Board asking for one. A resolution appeared to be imminent.

Meanwhile, Walt was preparing for the general release of Fantasia. It was advertised as a once-in-a-lifetime experience, accessible in only select theaters in the United States and with premium ticket prices. The studio had conceived of a new auditory experience called “Fantasound.” Special speakers installed around the theater played recordings of eight synchronized audio tracks. Chief engineer Bill Garity traveled to twelve major cities across the United States to supervise the installation of Fantasound units in those theaters.8 Over lunch, Walt told a group of his loyal animators that installing the Fantasound system cost $1,200 per theater but that union trouble with engineers in New York inflated the cost to $25,000. “He doesn’t mind the employees of the studio getting together and organizing,” wrote one of the animators at the time, “just so long as they aren’t told what to do by some outside bleeder.”9 (The twelve Fantasound units would end up costing the studio $480,00010—around three-quarters of the cost of Dumbo.)11

At the editor’s bay, The Reluctant Dragon feature required some live-action reshoots. It was for a sequence in an animation room where Norm Ferguson, Fred Moore, and Ward Kimball ham it up. The script had Kimball on camera drawing Mickey, but a rewrite changed the character to Goofy. On January 23, Babbitt was brought in as a hand-double to draw Goofy. In the completed film, the live hand in the brief shot is Babbitt’s.12

By the end of January, Disney management executed a new tactic to settle labor disputes. They put a labor specialist, a bombastic bootlicker named Anthony O’Rourke, on the company payroll.

Since 1934 O’Rourke had been an impartial chairman of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, drafting agreements between employers and employees. He professed having settled three to five cases daily. He said, “I told Mr. Walt Disney . . . that I would attempt to straighten out the confused labor conditions existing there, on two conditions: The first one was that I would decide all the cases in the same way that I act as impartial chairman for the Garment industry; and, second, that the decision would be final and binding. . . . Mr. Disney said, ‘That is exactly what I want.’”13

Soon a flyer appeared on the Disney bulletin boards advertising open meetings with “guest speaker Anthony G. O’Rourke” for all creative employees. At the foot of the flyer, its sponsor was printed in bold: THE FEDERATION.14

In these meetings, O’Rourke described his system for judging labor disputes, which he called the “impartial machine.” It consisted of a five-person court—two representatives from management, two from the employees, and an “impartial chairman.” “It insures just and equitable treatment of all grievances—large and small,” O’Rourke stated. This was accompanied by a reminder that the National Labor Relations Board had already designated the Federation as the sole union for Disney employees.15

In Hollywood, Columbia Pictures’s animation studio, Screen Gems, began negotiations with the Guild for a union contract.16 The Guild represented the forty-four artists at Screen Gems and, with MGM, two of the top six studios. Still unorganized were Warner Bros. animation, George Pal Studios, Universal Studios animation, and Disney. These six shops employed roughly 1,500 animation artists, including around 630 at Disney alone. Immediately, the Guild began its second campaign for Disney membership.

Babbitt was seething more than ever. The hiring of O’Rourke revealed that the Federation and the Disney company were in cahoots. He coolly decided how to return fire at the Federation, Lessing, and the studio all at once. And he had the ear of the AFL.

On February 3, the AFL filed a charge of unfair labor practice with the National Labor Relations Board against Walt Disney Productions, declaring that Disney “interfered with, restrained and coerced its employees and dominated and interfered with the operation and administration of the Federation of Screen Cartoonists.”17

Herb Sorrell withdrew the petition for an election. He argued that since the Federation was a company-dominated union, it was illegitimate. If the Federation unit at Disney did not disband, the AFL threatened to place Disney on the Unfair/Do Not Patronize list, prompting a boycott of Disney films and merchandise. The Labor Relations Board opened an investigation to determine the legitimacy of the Federation.18

This propelled the right-wing, Hearst-controlled press (like the Los Angeles Examiner) to call Sorrell a Communist. Gunther Lessing ensured that Walt saw this, and soon Walt was convinced. He held a meeting with his Personnel Department, noting, “I know that the head of the Painters’ local is a Communist. That is why they came out in the papers and gave him hell after he said they would boycott us.”19

The relaxed campus culture of the studio was slipping away. Tight budgets had caused the company to monitor the artists by the minute. Adelquist called it the “Control System.” Female secretaries, called “Control Girls,” stood outside each animation unit with time cards tallying the hours spent working and the hours spent idle. This was to determine the cost of each film, and the artists were trusted to fill them out accurately. The time cards were sent to the Time Office and processed on an early IBM machine. Idle time was reported to Adelquist, who saw that Babbitt consistently left his “idle time” space blank.20

The studio reported a $140,000 profit in the first fiscal quarter, thanks to revenue from Fantasia and with three more feature films—Dumbo, The Reluctant Dragon, and Bambi—slated before the year’s end. On paper the studio looked financially sound.21

Nevertheless, on Thursday, February 6, Walt’s office issued an urgent memo to all employees: “Statistics prove that the footage output of the plant for the past six weeks has dropped 50%. . . . The Company recognizes the right of employees to organize and to join in any labor organization of their own choosing, and the Company does not intend to interfere in this right. HOWEVER, the law clearly provides that matters of this sort should be done off the employer’s premises and on the employees’ own time. . . . This is an appeal to your sense of fairness and I trust it will be sufficient to remedy the matter. Sincerely, Walt.”22

This memo rankled even some of Walt’s more loyal artists. One remembered, “This appeal to our ‘sense of fairness,’ coming from the man who had reneged on his promise to pay us twenty percent of his profits from Snow White.”23

Additionally, it didn’t appear that the company truly recognized the right of employees to join in any labor organization of their choosing. Gunther Lessing stated publicly that same day, “The Federation of Screen Cartoonists was certified to us two years ago by the labor board as bargaining agent for the employees and until the NLRB certifies someone else we will continue to recognize it.”24

It was clear what the Disney Guilders had to do. If Lessing was claiming to obey the Labor Relations Board’s old ruling, then they needed a new ruling. The Guild had to get certified by the Labor Relations Board.

That night the Guild held a mass meeting at Hollywood’s Roosevelt Hotel studio lounge. Speakers included Aubrey Blair of the AFL, Guild attorney George Bodle, Herb Sorrell—and Art Babbitt. What made this meeting momentous, however, were speeches by two of the country’s most celebrated thinkers, Donald Ogden Stewart and Dorothy Parker. (Both had protested alongside Sorrell in February 1940, and both were members of the Screen Writers Guild.)

Parker’s speech held particular punch. She talked about working for the women’s suffrage movement more than two decades before, and recently fighting a company union alongside the Screen Writers Guild. “I think the two words company union form the filthiest phrase in the language,” she said. “Our Screen Writers Guild is going strong now. But—it took more than seven years. That’s what I wanted to say. That’s the ugly warning. Don’t throw away seven years.”25

Just as the Screen Cartoonists Guild had an MGM unit and a Warner Bros. unit, the leaders of the meeting planned to form a Disney unit. The next meeting was scheduled for the following Monday, February 10, at 8:15 PM.

On Monday morning, Disney management posted a memo on the bulletin board: “IMPORTANT MEETING TODAY! Place: Theater. Time: 5:00 o’clock. Subject: Talk by Walt.”26 All production staff were required to attend.

As the artists entered the large theater, Walt positioned himself near a microphone, where he was being recorded. At thirty-nine years old, Walt did not consider himself a public speaker. There was nervousness in Walt’s voice as he read from his fifteen-page script:

“In the twenty years I have spent in this business, I have weathered many storms.” Walt then talked about his life of struggling to make animation “one of the greatest mediums of fantasy and entertainment yet developed.”

Babbitt was in the audience. He, too, had been part of the medium’s development—from the art education that evolved into a Disney art school, to the character analysis that endowed characters with personality, to the live-action reference that analyzed movement.

Then Walt described how the war in Europe had eliminated half the market. “There are certain individuals who would like to blame the executives of the company for not foreseeing this calamity that was caused by the war in Europe. I think that is unfair. I ask you to look at what happened to France. I ask you to look and see what England and America are doing now, frantically trying to prepare themselves. If they didn’t know, with all their ways of finding out, the true condition of things over there, how can anyone hold us responsible?” Walt went on to describe how much paid vacations and sick leave were costing the company.27

Walt had spoken to his artists from the lens of a businessman, and they filed out of the meeting feeling more polarized than ever. What Walt did not express to his artists were his own feelings about the future. He didn’t level with them. Pinocchio and Fantasia had yet to recoup their costs, and the studio was quickly sinking back into debt.

There was a huge turnout at the Screen Cartoonists Guild meeting that night, with the Guild counting more than 250 Disney members. The official Disney unit of the Guild was formed and its officers nominated. Babbitt was nominated for chairman. The deciding election for officers would be held by mail-order ballots to be opened during a meeting on February 18.28

Soon after the nomination was made public, Lessing invited Babbitt to his home for dinner. “We had a drink or two and talked a little bit about everything,” said Lessing.29 Then he asked if Babbitt was going to accept the Guild’s nomination. Babbitt replied that he would.

Lessing told him that the lower-ranked people he was fighting for weren’t worth it. He added that if Babbitt were smart, he would make sure that he suddenly became too “sick” to accept, or just go away for a few days. Otherwise, Lessing cautioned, he was going to get himself into a lot of trouble.30

Trouble or not, the Guild was rising in numbers. Walter Lantz, the animation producer of Universal Pictures, was preparing to sign with the Guild. There was one hiccup, though: half of Lantz’s artists had formed a company union called the Walter Lantz Employee Association. This was oddly parallel to Disney, except that with Lantz, negotiations progressed steadily, and the Guild triumphed without a strike.31

On Tuesday, February 18, at the big Guild meeting, Babbitt was elected chairman of the Disney unit. Hilberman was elected secretary. (In addition, the vice chairman was airbrush artist Phyllis Lambertson, and treasurer was animator Tom Armstrong.) A tentative union contract was discussed and submitted to the committee.32

Another issue was also discussed, settled, and put into action—and it would not bode well for Lessing and Babbitt’s friendship.

Gunther Lessing must have thought he was doing great as a labor specialist. Starting Monday, February 24, he put forth a new pay scale for the Ink & Paint Department. (The wages still started at $16 but could grow by $2 or $2.50 every three months to $37.50—barring termination.)33

Then on Wednesday, February 26, Lessing found a shocking carbon-copied letter on his desk. It was from Guild president Bill Littlejohn and addressed to the head of the Painters District Council, requesting severe action against the Disney company. Littlejohn charged Disney with refusing to negotiate with the Guild, deliberately scheduling work meetings in conflict with Guild meetings, and attempting to revive a defunct company union. Therefore, the Guild asked the council to adopt the resolution to put the Disney company on the official Unfair/Do Not Patronize list of all AFL affiliates throughout the country. It was another boycott threat.

Lessing immediately called Howard Painter, the Federation’s new lawyer, and asked if the Guild’s Disney unit had authorized this. Painter didn’t know, so Lessing summoned Babbitt into his office and asked him directly. Babbitt replied that he knew nothing about it. Lessing asked him if a boycott was a fair tactic, and Babbitt played dumb. Later that day, management officials called Babbitt into a conference, and Babbitt repeated his response.

The next day at the studio, Babbitt had a different story. He told a Federation chairman (possibly Bill Roberts) that twenty-five members of the Guild’s Disney unit, including himself, had approved the resolution.

This infuriated the Federation supporters, and bulletins from both the Federation and the Guild bombarded the bulletin boards. The Disney company posted a bulletin headlined, IS DISNEY BOYCOTT IN HANDS OF MGM GUILD?34 Another read, ARE THESE 25 TO JEOPARDIZE YOUR FUTURE AND THAT OF YOUR 1100 FELLOW EMPLOYEES?35

Lessing’s handbills may have been meant to sow doubt in the Guild’s leaders, so Babbitt posted a bulletin of his own: “CALM DOWN BOYS!! Mr. Lessing is a nice guy and a very smart attorney. He should be able to recognize his own tactics.” As opposed to all of his previous posts, this one was boldly signed ART BABBITT, adding a derisive “P.S. May I compliment the Federation on its very close cooperation with the studio attorneys.”36

Now when Walt saw Babbitt pass by, his eyes followed Babbitt. Walt whispered to his staff that this top animator had become a “Benedict Arnold.”37