I SHOULD FEEL GOOD ABOUT MYSELF. According an article in USA Today, the average American man in his fifties weighs 199 pounds. Me, I’m usually 185 when I weigh myself first thing in the morning. I’d always thought I was average for my height, gender, and age, but here was proof that I’m 14 pounds lighter. The article piqued my curiosity, leading me to wonder if I’m any lighter now, compared with my peer group, than I was at earlier ages.

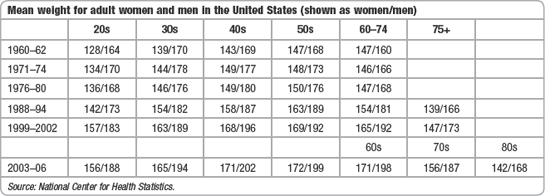

Using data from the National Center for Health Statistics, I put together the following chart. The vertical axis shows the years in which data was collected, and the horizontal axis shows mean weights for American adults by age. (For the statisticians: I refer to “average” weight above, which is how USA Today described the data, while the studies actually show “mean” weight, meaning equal numbers of people weigh more or less than the figures shown.)

What I discovered isn’t particularly impressive. My current weight is 93 percent of the mean for men in their fifties. Over my lifetime I’ve typically been between 91 and 94 percent of the mean for my age at the time of each survey, although I bulked up to 104 percent at one point in my late thirties. This was during my late-to-the-party attempt at bodybuilding, at which I failed pretty spectacularly. But aside from that blip, a lifetime of serious exercise has kept me in more or less the same place, relative to my peers.

I encourage you to run your own numbers; just divide your weight by the mean for your age and gender at each time point. It gives each of us a baseline to keep in mind when we talk about how and why Americans have gotten so freakin’ big in such a short period of time.

TELL ME WHY YOU FRY

That we’ve gotten massive is beyond dispute. That we eat more than we used to is beyond dispute. But in the past few years I’ve seen all of these additional hypotheses suggested as reasons for the girth of our nation:

Those are the big ones. They’re all “true,” in the sense that we can find data to back them up. They all make sense. Most of us have sedentary jobs. We all know the food chain makes the worst stuff cheap and the best stuff expensive. And no one with a mind open to science and reason denies the genetic roots of both behaviors and outcomes. You can’t take a body that’s thick by design—the loving creation of a human life by two people whose DNA tilts toward XXL—and make it thin. Not only is it physiologically impossible to do such a thing without surgery or powerful drugs, it’s stupid and immoral to suggest that all of us should have matching silhouettes. I have a thin mom and a fat dad, and somehow ended up with a narrow frame. Most of my siblings struggle with their weight. Same deck, different cards.

Still, I can’t help but lean toward the “bad choices” hypothesis. It comes closest to matching my experiences and observations. If you’ll indulge yet another of my rambling stories:

I went to a Catholic high school in a semirural part of Missouri. The suburban-sprawl kids like me were a minority. Most of my classmates had deep roots in small towns. Some were farmers. As much as I observed anything beyond girls and sports, I noticed an odd type of couple: a solidly built man married to an obese woman. I can’t recall seeing that in the suburbs; if you saw a mismatch, it tended to be more like my parents, where the male was soft and pot-bellied and the female more concerned with her figure.

Something else I noticed: The farm boys were the biggest and strongest in the school. My football coaches and teammates were anti–strength training but pro-farming. Some of the biggest kids spent their summers throwing hay bales onto flatbed trailers. Some of the skinniest kids (like me) lifted weights. So almost everyone assumed that it took a lot of repetitive work each day to get big and strong, something you couldn’t possibly achieve in a few hours a week in the weight room.

But it wasn’t simply exercise that made the farm kids bigger and stronger. It was the way they ate before and after they worked the fields. Farm kids consumed far more calories than the rest of us, as did their parents. That explains why male adult farmers so often seemed half the size of their spouses; they ate the same way, but the men burned most of it off outdoors while the women (who were hardly sedentary) spent more time indoors. It also explains why I was still skinny despite my work in the weight room. I went home and ate like everyone else in the suburbs. We had our meat, potatoes, and dessert, while my farming peers were eating all that plus biscuits, corn, and butter. Given my age, metabolism, and activity level, I was probably undereating by hundreds of calories a day.

I’ve fallen out of touch with my classmates, but I still get the alumni newsletter, and what I saw in one issue just shocked me. It was a picture of a group of alumnae, most from my era, who’d volunteered for something or other. They were absolutely huge. I doubt if a single one was an actual farm wife, but they’d all managed to grow to that size, if not beyond. These weren’t strangers riding electric carts in Walmart, people we look right past without wondering how they got that way. These were people I once knew, whose potential adiposity wasn’t at all apparent in the 1970s.

I get that humans have the ability to store calories; it’s an evolutionary trait that helped our species survive when food was scarce. In past generations, when it was fashionable to stuff themselves, the upper classes did exactly that. According to Bill Bryson in At Home (a terrific history of how we came to live and eat the way we do), this was a recommended menu for a six-person dinner party in the mid-nineteenth century: mock turtle soup, fillets of turbot in cream, fried sole with anchovy sauce, rabbit, veal, stewed beef, roasted fowl, and boiled ham, followed by a long list of desserts.

While gluttony wasn’t an option for most people, those who could afford the food (along with the household personnel to cook and serve it) ate fantastical quantities. And of course they grew to fantastical sizes. America’s heftiest presidents, ranked by our best guess at their body-mass index, all served consecutively in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: Grover Cleveland, William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt (who was also our most physically active president), and William Howard Taft, who weighed an estimated 340 pounds when he left office in 1913.

This was decades before the invention of fast food.

History shows that people who want to consume massive volumes of food have always done so, as long as they have motive, means, and opportunity. The open question is why people of our generation, who don’t want to eat to excess and desperately want to avoid storing fat, get big anyway. Let’s explore.

NEW RULE #17 • It’s actually kind of hard to gain weight.

There’s a pernicious myth, propagated by health and nutrition professionals who should know better, that weight gain and weight loss are linear processes. Add a single cookie to your daily diet, the public is told, and over time it adds up to dozens, if not hundreds, of pounds. It’s not true. As two Dutch researchers explained in a commentary in the Journal of the American Medical Association, over time your body will adjust to the extra calories, along with whatever weight you gain initially. That amount of food—your previous diet plus the cookie—becomes exactly what your body requires to maintain its new, higher weight. You have a long list of hormones and metabolic processes to stabilize your weight… as long as you don’t add any more cookies to your daily diet.

Even then, it’s kind of hard to supersize. Your body upregulates your metabolism and downregulates your appetite to compensate for any new infusion of calories. The researchers used the example of a twenty-five-year-old male who has a body-mass index of 25, the edge of what we consider overweight. Let’s make him five-foot-ten, 174 pounds. If he kept his activity level exactly the same over the next twenty-five years, he would need to eat an extra 680 calories a day to reach a BMI of 35, the midpoint between “obese” and “Holy crap, is that guy fat.” He would weigh 244 pounds.

You could argue that no one would actually maintain the same activity level while gaining 70 pounds, and I’d agree. But at a higher weight he’d burn more calories with every step, so he could move a lot less and burn the same number of calories he did at 174 pounds.

How much he moves is really beside the point, which is this: We’ve been told for eons that a pound of fat is 3,500 calories, and an extra 500 calories a day should increase your weight by a pound a week. That would be 52 pounds a year, and after twenty-five years we’d be looking at a man who weighed close to 1,500 pounds—three-quarters of a ton.

Do you know someone who weighs more than a thousand pounds? I doubt if I’ve ever met anyone over 500. And yet, all of us know people who weigh at least 70 pounds more than they did a quarter-century ago. Some of you reading this have gained that much, and more.

Which brings us back to the original problem: How did something that should be really hard become the signal feature of our generation?

NEW RULE #18 • We don’t really move less.

Along with the myth that weight gain and weight loss are linear and easily quantifiable is the notion that all of us move a lot less than we used to. I’ve always believed this to be true, despite the fact that I grew up at a time when adults hardly moved at all. My father and the other men of his generation had grown up in the Depression and served in the military. They reveled in their suburban leisure. In my neighborhood you rarely saw a middle-aged man do anything more strenuous than mow a lawn or trim a hedge on a Saturday. Even then, the work was done by mid-afternoon, and the drinking started soon after.

Women certainly moved more than their husbands. Someone had to shop and prepare food for all of us baby boomers, and those ranch houses didn’t clean themselves. But it’s not like they were taking daily Pilates classes.

Research now shows that our generation probably doesn’t move less than our parents’. A 2009 study in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition calculated how much food we had available in the 1970s versus the 2000s, subtracted the amount that’s thrown out or wasted, and showed that weight gain correlates pretty well with the higher volume of food we eat. If anything, their data suggest that we probably move more now; otherwise, the average American adult would be about five pounds heavier.

Moreover, it takes a lot of movement to counteract all that food. Harvard researchers reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association that middle-aged women who gained fewer than five pounds over a thirteen-year period averaged about sixty minutes a day of exercise.

That leaves us with one remaining suspect in the fattening of our generation.

NEW RULE #19 • Tasty food makes it too easy to gain weight, and too hard to lose it.

Weight-loss researchers long ago gave up on the idea that all members of a species react to food in the same way. When they study mice or rats, they genetically modify them to make them more or less susceptible to whatever stimulus they plan to administer. They can’t modify humans, but that doesn’t mean we’re all the same to begin with. An exercise study I quoted in Chapter 4 divided subjects into “responders” and “nonresponders.” It works the same way with nutrition. Researchers know that some people simply respond to food with less inhibition or satiety than others. They’re hungrier, and they eat more before their appetite-control mechanisms kick in.

So which are you? Come on, you know. If you sometimes lose control of yourself when eating, gain weight easily, and hang on to everything you’ve gained, then you’re the human equivalent of one of those obesity-prone lab animals. It’s what you are, and it’s what you’ll always be. Someone who’s obesity resistant, like me, will still gain weight when we eat highly palatable food without restraint. But we’ll also lose it when we stop eating the things that made us fat. I know it’s not fair. As Denis Leary said, “Life sucks, get a helmet.”

NEW RULE #20 • every pound you don’t gain is one you don’t have to worry about losing.

Ask a weight-loss researcher what works for people genetically susceptible to weight gain, and if she’s honest, she’ll say something like this: “Don’t gain weight in the first place.” If it’s too late for that, then you’re stuck with the same old advice you’ve always gotten from people like me: Burn as much energy as you can with your training program, and modify your diet to take care of the rest.

You know what not to eat. You know that highly palatable foods—those engineered to contain unnatural amounts of sugar, fat, and salt—are both irresistible and unsatisfying. You can’t stop eating them once you start. (Most of us are old enough to remember the Lay’s potato chip ads, which used their inability to satiate as a selling point.) That’s true for everyone. Whether we’re talking about snack foods, Big Gulps, movie-theater popcorn, big-chain pizzas, or french fries, we know we can’t stop once we start. The only strategy that works is to avoid those things entirely.

Slightly less obvious is the need to avoid foods that are your personal triggers. A trainer I interviewed for a magazine article advises his clients to “know your Kryptonite.” For me it’s pancakes, donuts, and all the other stuff that falls under the “dessert for breakfast” rubric. I wake up hungry, and if sweets are an option, I’ll eat far more than I can burn off with any amount of activity, including Alwyn’s workouts. For someone else, it might be a couple of drinks. Alcohol is only mildly associated with weight gain, if at all, but its reputation for lowering your inhibitions is well deserved. If your night of drinking typically concludes at the nearest White Castle, the problem isn’t really the sliders and cheese fries. You wouldn’t end the evening there if you hadn’t started at the pub.

Two more ways to control your environment:

My big points are these: