Degrees of Gray in Philipsburg

The streets of Philipsburg do indeed seem laid out by the insane. Beyond West Broadway pavement gives out, and from then on the roads and streets are a seasonal affair, running with mud or bleached by dust or silent under new snow. Many of the streets that cut through town barely qualify as such; they are paths beaten in the grass, two tracks where trucks lurch over rocks with a clatter of bad linkage, roads of gravel or red cinder that skirt empty pastures and a few last houses until they head, somewhat pointlessly now, into the hills and mountains where men once worked. One can imagine many things about these evocative streets, and in some ways that’s all that remains, imagination haunting a town where even history, usually the last to leave, has given up and gone away. One can imagine, for instance, that the roads are the ripped seams of a civilization, rents in the fabric that have led to a general unraveling, to the vacant storefronts and faded signs and a rusting school bus, still yellow, inexplicably parked in front of a hotel whose last guest signed his name to the register, one vanished afternoon, years ago. Perhaps the bus died there, the children walked to school that morning, and it was convenient and reasonable—since weeds had already grown up around the red brick steps and the windows were gone and the hotel, it was agreed, by some vague assent, was never coming back—to leave the bus where it was, like the carcass of a whale washed to shore. Time would take care of it, as it had the hotel. Now the bus has no windows, and who knows what became of the children. You don’t see many of them on the streets of Philipsburg.

One can imagine the roads—somehow the word streets implies too much, is too elaborate—as the relics of haste and ambition, of a boom in silver that lasted a few short years, until the Repeal—and that word, repeal, seems fitting for a town whose future was never in its own hands—disrupted the hurried energy, and in fact crimped the flow of time generally. Houses had been flung up on the hillsides, and there was some need to connect them, but the original roads were probably platted by the tramping of tired men. That weariness, that exhaustion, is inscribed in the roads to this day. Things of course changed, but in some ways time reversed direction and began running backward, seeking the past as water does low level. But nostalgia, where loss finds rest, hasn’t really taken root. Philipsburg’s rival from the boom era, Granite, several miles back in the woods, higher and colder and more remote, is a ghost town now, the last resident, holding out as he worked a small claim, having died seventy years ago. You can walk those streets and still find the infirmary and the bank vault and the music hall and, pointedly, down a gully, the obligatory red-light district that always seems to follow wherever the work men do is an insult to their bodies. Presently someone is trying to rebuild the town, hoping to attract tourists, and on most Sundays in the summer, a few desultory visitors wander with a photocopied map through stands of stunted pine, looking, somewhat puzzled, at walls of leaning brick or the fairly intact stone house of the superintendent. Some of the shacks where miners lived still have their sad beds shoved into a corner, although those shacks are so small they seem to be made up solely of corners. A black stove, a chair by the window, and the space is filled. The size of these clapboard shanties doesn’t suggest children, and it’s as if the future, even from the beginning, was something you would have to establish in another town. The past was Granite’s destiny from day one, and when the mines shut down for good, what was left of that past was packed up and moved in carts three miles down the mountain, settling in Philipsburg.

Entitling a poem or story or essay is harder than naming a child. The privilege of place is almost like a law of primogeniture, with the title inheriting the entire work, and along with that legacy comes the burden, the implied promise, of carrying the weight of the piece to the end. You want to avoid the didactic as well as a too vaguely allusive reference that will read portentously. Joyce named things well—“The Dead,” A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Ulysses—suggesting by example that simplicity and a certain cool aim at the center of a work is the way to go. Hugo’s title goes that way, and yet I’ve always liked it, in part, because shadings of gray refer to weather, and weather is mentioned only once, obliquely, in a line of the poem where, even then, the accent falls on another word. This seems characteristic of a poet who is both blunt and self-effacing: the poem avoids wallowing in its most obvious mood. But while we’re promised degrees of gray, like a chromatic study in painting, we descend through the poem, down through the broken self and ruined history and a stanza of questions with no satisfying answers, until we arrive at the final lines, in which, suddenly, a slender girl’s red hair lights the wall. To a point, in other words, where the color red is the hero of the poem. Hugo is an honest writer, and his title is honest, I believe, but the light and youth and especially the vivid red, discovered down at the bottom of everything, is the one note in the poem that has always put me in a questioning, objecting state of mind. I’ve always felt—just vaguely, like a hitch in my reading—that Hugo pulled the red out of his hat.

After the onslaught of loss, both personal and historical, do we really believe a good lunch and an aesthetic perception settles the matter? Does red (and, by inference, poetry) save? Quite possibly poetry salvages nothing except language itself, and even that project of reclamation is up against poor odds. Poetry is not a social program and it’s not easily accessible to everyone, despite its ancient mnemonic role and the currency of certain opinions by primitivists of the New Age. Nor is poetry liturgical, composed of sacramental language and containing a central mystery that can be approached, shared, and repeated, then made portable and evangelized and kept alive through ritual until its power rivals governments. The Pauline hopes of poetry recur now and then—in Shelley or Brodsky, for instance, or Edward Hirsch—but they don’t result in many converts. Reading poems remains a cult practice of the few, and it’s hard to imagine an art form further in temper from the reality of Philipsburg. Hugo’s red might be epiphanic and passing, one of those visions we expect a poet to access, an insight confirming our solitude rather than rescuing us from it, but if this is so, does he really touch the ruin so richly itemized in the rest of the poem? Hugo’s no aesthete, and he means for this red to be a real outcome, an inevitable result of looking directly at the degrees of gray. Because he’s a poet, we have to take him at his word. Hugo says there’s salvation in poetry, a saving, moreover, discovered at the bottom of ruin, and he’s also suggesting, I think, that you must fall to find it.

I don’t want to bog down in the exegetical rigging of real criticism, the cumbersome quoting, the whole vast tackle of arcane and specialized language that takes poetry further toward silence. Hugo’s poem doesn’t require it. It’s written in free verse, sprung from the inner clock that keeps time in metrical poetry, and so the lines read like regular sentences, denser but not all that different from the ones in a daily newspaper. The poem’s not fragile. You can beat on it. It’s got good traction. Paraphrased, its four stanzas go like this:

1. You’re fucked.

2. We’re all fucked.

3. Why?

4. Let’s eat lunch.

It isn’t easy to say your life broke down. It isn’t easy to say in conversation and expect anyone to listen, and it’s desperately hard to say in poetry or prose and expect anyone to read. From my own experience I know the result, most of the time, is laughable. On a personal level, the problem seems to be that we know these things happen, but we don’t ultimately know why they do, and anyone who steps forward too ready with phrases from pop psychology or offering details from personal history is either missing the deeper point or airing gripes. The problem for the poet is one of expression; nothing is quite so false, in writing, as the heartfelt confession. Irony in its least waggish form, scrubbed of cynicism, is necessary—a certain cool, a distance, the slight masking that occurs whenever the writer separates from his subject. Hugo’s solution is to go for blunt, and most of this poem trades in symbols that batter the obvious, from broken-down cars to crazy streets to churches and jails and a prisoner, not knowing what he’s done, who stands in for the state of the soul. The symbolism here is too much in the public domain, too shared for this to be a private excursion. Even if you wanted to, you couldn’t wring a proprietary solitude from it. When Hugo says your life broke down, that’s either metonymy or synecdoche, but we get the point, that its absent term is a car, and we accept it because of the banged-up humor and his refusal to be pretty about it. The directness is disarming, and it serves the subject—even our most durable, readily available solutions have failed. These symbols create a loneliness and isolation because their communal function has failed, but we still recognize their ghostly hopes as our own. In a single stanza Hugo sweeps up the whole of Western civilization. There are plenty of mouths, but the kiss that really eludes us is the good one—failed love. The streets are nuts, they either don’t go anywhere or, if they do, all the destinations are dead ends—failed thought. Churches are kept up, but a church qua building is only a maintenance problem, no longer in the business of salvation—failed spirit. The hotels haven’t lasted, and the jail’s already lived out its Biblical allotment of years—failed alibi, law. You’re a wreck, but you’ve come to a place that’s an even worse mess—failed individual, society.

The auxiliary verb might subtly, brilliantly alters the universe, so that the you is not the poet addressing himself, or not strictly. If, instead, Hugo writes: You came here Sunday . . . then we’re into confining facts, confessional accounts, moving a step away from the poem as written, with its broad, inclusive you, toward the self as a dead end, seeking private salvations. The you would then become the poet or a character standing in for the poet, and in any case, whatever hope or possibility the poem holds would be bracketed by the past tense, framed inside personal history, absorbed into a character whose formation was completed some time ago—into a world, in other words, that occurred, once and for all, prior to the poem. The perfect past would isolate the poet from his poem, quarantining the ruin to a time and place that’s already been safely escaped; the poem would be the artifact left behind by an experience, losing an element of risk. Using the auxiliary might shifts the tone. We enter the poem through supposition, and are given, like an allowance, a small sum of uncertainty, to spend wisely or foolishly. By rescuing the first line from a finished past tense, might hints at a future, particularly in the sense that anything unknown belongs to an expectant time. It plants a seed of probability or possibility, even advisability. The word’s brassy note rings like a harmonic, its long vowel sound finally flicking light against the wall. But how do we get there?

In this first stanza, the lines are typically short and flat, somewhat immobile, and the one line that departs from the pattern, the longest and most fluent, is about movement, particularly walking and acceleration. It’s as if the poem panics inside its contracted space. Pathetically, it wants to go somewhere. The syntax is an echo of the sense, and there’s fear and alarm in the sentence, a struggle between understanding and action, capturing a moment of awareness and the ensuing paralysis, when flight is the right impulse but the urge has atrophied and there really isn’t anywhere to go. Each hurried clause is like a frightened, fading footstep. And then the urge dies, the brief flight stops, and the sentences, abrupt as walls, return to their immobility. The prisoner is always in—a curious phrase, in that he doesn’t seem to be held against his will. He doesn’t need to be. Awareness is gone, and with it, freedom. His imprisonment is a condition. He’s bound to a cell by “not knowing,” which isn’t a defect of mind, but of comprehension, one we all share regardless of native gifts. That the prisoner lacks understanding might serve as a legal argument for his innocence, but no ruling, for or against, will release him from history.

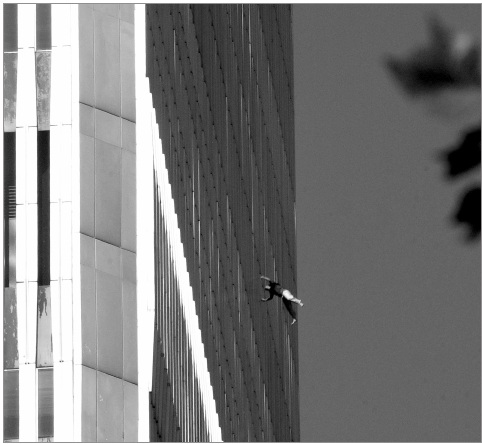

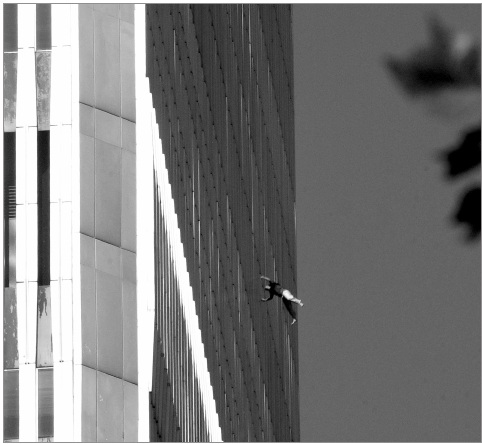

Philipsburg is located in the Flint Valley, a valley so open and wide all movement along the highway feels annulled, and on the morning of September 11 nothing here changed. The vast space seemed to cancel out even conversation, and there was no rush to talk about the attack in New York. I’m not now inclined to fill this silence with supposition, to hazard guesses about the particular quality of the quiet in Philipsburg, except to say I felt it myself. While I can imagine people in New York or Boston or Omaha stunned by fear and outrage, that wasn’t my situation, and I remember standing outside that morning, looking across the valley where already, in the higher elevations, snow had fallen, and feeling nothing, not horror or disgust, not shock or anger. A branch snapped by a surprising June snow, a dry hummock up the hill where fox denned in winter, these things held my attention, standing out, strange and real, in the nearby world. It may be true that we are ultimately saved from total loss, as Czesław Miłosz has written, because there’s nothing to do but stare at the green leaf fluttering in the wind. Much of the news, as a form of expression, made little sense to me. People were saying our lives would never be the same again, a phrase turning naïvely around a moment that space, which is heartless, and nature, which is indifferent, would never share. Not even history agrees, and part of what made discussion so difficult was the intrusion of the historical into a romance, a confusion of genres we find particularly galling. Hawthorne called romance “a legend prolonging itself,” whose hostile enemy is contact with history. Without any real conscious intention, I would find myself seeking a sense of that contact, turning to the work of Miłosz and Joseph Brodsky, writers who, knowing firsthand the horror of history, struggled between silence and noise to make their poems. But before that, days, a week after the attack, as voices emerged, as newscasters spoke, as opinions were aired, with noise becoming the norm, I found a photograph of a falling man that seemed to restore a necessary silence, and I pinned a copy to my wall. It seemed to me a place to begin, the only place.

Whereas prison, well, what is it, really? A shortage of space compensated for by an excess of time.

—Joseph Brodsky

Brodsky’s equation is just, I think, but you can tinker with the terms and arrive at other prisons, other compensations. This picture also brings us to a prison, one without a shortage of space; in fact, there’s a sudden, horrifying excess, a terrible liberation, with time in short supply.

In this moment the falling man’s time on earth is a spatial concern, and he has more in common with a stapler than he does with you or me. Natural laws explain why he’s dropping, and a formula can easily calculate the rate of his descent. A man of roughly that weight, from roughly that height, in that specific gravity, arms and legs spread, reaches a terminal velocity of 125 mph, beyond which there’s no further acceleration. Terminal velocity—of the man, a stapler, a raindrop—is the square root of [(2 x W) / (Cd x r x A)].1 That’s the irresolvable contradiction in this picture, a man subject to mechanistic forces, a life obedient to an indifference—although obedient is a somewhat dead metaphor here, since rebellion or refusal is impossible. One might wonder if he jumped or not, a last act of volition, a final insistence on self, but either way falling is the consequence. In falling, he’s lost connection, he’s ripped free from every relation, to his love and work and family, to his own biography, to the choice he made that morning about what shirt to wear. The descent strips him of every cherished thing, even our regard, and one thinks of Auden’s Old Masters who understood the position of human suffering, “how it takes place / While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along,” and the amazing boy from Breughel, falling out of the sky, seen by a ship that “had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.” The falling man is falling because that’s what things do, and in some awful way it’s not remarkable.

Just the same, there’s an abstract purity to the picture, in the geometry of sky and building, that strangely suspends the man in a constructed space, entirely drained of time, so that one imagines him there forever. The composition is immaculate, even icily harmonious. In the picture’s arrested moment you get a pure feel for the falling man’s incomprehension, his emptiness, but in the days following the attack, obviously, this sensation would become intolerable to survivors, to the witnesses we were turned into, and the point of view would shift, the images would progress. Something was needed to distinguish the falling man from a fluttering scrap of paper, from the nothing of his silent descent. The pristine space began to blow with dust and fill with debris. Attention was focused on the broken hierarchy, the jumbled ruin. An accessible idea of heroism, Homeric but not tragic, occupied the human void, and suddenly firemen loomed up and moved across the foreground of the new images. “The savagery of the struggle for existence,” Miłosz has written, “is not averted in civilization,” and now we knew this, possibly. But a hasty gloss of evolution from primitive to modern was improvised, phoenixlike, out of the ashes, and contra the terrorists, who seemed to have reduced a symbol of at least one kind of civilized aspiration to a barbaric rubble. Rebuilding began in a rudimental, dark, superstitious state where blind luck or chance either saved or did not save. Later, it turned out that God was with the people who survived and the people who perished were now with God, a tautological tidiness that always breaks my heart, tearing at an old longing for universal justice. Faces were shown, names mentioned, chronologies elaborated, stories told, helping to rehabilitate the present scene, applying a patch to the moral sense. An ideal civitas emerged, so that, looking into the shadowy precincts of Wall Street, where certainly some of the dead were embezzlers, no mention was made of precisely the sort of intrigants who would, later, populate stories about Enron. It’s almost too obvious to state, but in a random sample of any three thousand people, some will be beating their children, others will be addicted to heroin, and others still will be caught in the midst of affairs that would, left to run their course, damage families and undo to some degree the social fabric. But this was a new polis—from which those folks were now symbolically banished. Sincerity worked like a conduit for connection. What might have been viewed as a great equalizer, falling on the just and unjust alike, visited on the rich and the poor, the fair and the homely, black and white, instead rose out of the wreckage with a perfectly familiar face, looking quite the same as life before. Hierarchy was restored, and hatred with it. Enemies were declared, war was in the offing, and now the falling man, not knowing what he’d done, was descending through—or perhaps into—the medium of history, which sits between all of us and oblivion.

There has been considerable reflection on the origins of the phenomenon known as individualism, on Byronic despair—the revolt of the individual who considers himself the center of all things, and their sole judge. No doubt, it was the contents of the imagination itself which forced this to happen, as soon as hierarchical space began to somersault. Anyone who looks into himself can reproduce the course of the crisis. The imagination will not tolerate dispersal and chaos, without maintaining one Place to which all others are related, and, when confronted with an infinity of relationships, always relative only to each other, it seizes upon its sole support, the ego. So why not think of myself as an ideal, incorporeal observer suspended above the turning earth? [Italics mine.]

—Czesław Miłosz

Hatred organizes space—think of Dante’s Inferno, the structure of which is partly animated by personal enmity—and in the gray waste of the Philipsburg in Hugo’s poem, it’s the principal supporting business. The contracted, hating ego restores hierarchy, creating an armature for the emotions, organizing a defense of the inner life while it’s attacked from outside. But hate and rage are emotions we summon to survive a crisis, and the acute phase can’t be sustained for long. The adrenal medulla can’t hack it. The surge of epinephrine is meant to peak and subside and pass entirely with the passing of the injury or threat. Without relief the nerves blunt, and even if the emergency remains, a numbing settles in obdurately; and that’s the harmed, sinking, downward passage, from hatred to boredom, captured in the second stanza of the poem. Hugo moves in a quick line or two from rage and hatred to boredom, and I think he’s right to push the association. Here, the hatred is against history, the mere unfolding of life, its indifferent or brutal or oblivious progress, against which the spiked rage can’t strike out. It’s a grievance against ghosts, a grievance against what’s gone—or even, more accurately, against the sheer “going” of life everyone suffers. No wonder that in these ruined Western towns you so often find revivals along the lines of Hawthorne’s legend prolonging itself, the sorry romance of the spurned, yearning to occupy the dramatic center once more by suspending time. The main drag in Philipsburg is either ruined or vacant or shabby or somewhat tartly gussied up, but these are all guises of the same settled arrangement, the same hierarchy. Hatred’s destination is boredom, and boredom is perhaps a rebellion against time; it’s the finished putting up a fight with the end. Boredom is, at any rate, a more habitable space, long-term, than history.

The British psychologist Adam Phillips calls boredom “that most absurd and paradoxical wish, the wish for a desire,” and defined as such, boredom isn’t fixed by distraction, by bars or restaurants, but by the arrival of a feeling of anticipation. I know for myself boredom involves a spatialization of time; the forwardness goes out of life, and I wait, and in waiting time becomes a place—not a particularly good one, but a place nonetheless, with the minutes and hours, the days and months piling up indifferently. For phenomenologists, this kind of repetition isn’t a property of time but of space, and then it’s more aptly called “redundancy,” when things exceed what’s necessary. In boredom you take on some of the character of an object, becoming lifeless and inanimate, lacking flow, and the more the time sense is rendered into space, the more isolated you become—isolated by becoming extraneous. The spooky intimation behind boredom, the whispered secret of it, is death, a final draining of time, when at last all the living belong exclusively to space. In boredom, we become victims of a sameness within a hierarchy whose original principle of design was a now-forgotten, vestigial loss of proportion—which is an aesthetic problem, the problem of arranging parts harmoniously within a whole.

What is worse, time, always strongly spatial, has increased its spatiality; it has stretched infinitely back out behind us, infinitely forward into the future toward which our faces are turned. . . . Today I cannot deny that in the background of all my thinking there is the image of the “chain of development”—of gaseous nebulae condensing into liquids and solid bodies, a molecule of life-begetting acid, species, civilizations succeeding each other in turn, segment added to segment, on a scale which reduces me to a particle.

—Czesław Miłosz

When hit by boredom, go for it. Let yourself be crushed by it, submerge, hit bottom. In general, with things unpleasant, the rule is, the sooner you hit bottom, the faster you surface. [Italics mine.]

—Joseph Brodsky

To fall and hit bottom life has to give up its hold on the horizontal, its restriction to the same level in a now-tedious hierarchy. For this, there’s no choice but to descend, if only because hatred, that forgotten structure inside boredom, has already failed in its attempt to rise above history and circumstance. Upward progress is a social or economic idea, but from literature and, to an extent, religion, we know going down holds a lot of life’s interesting possibilities. If up isn’t an option, then down is the obvious alternative; it’s even desirable. Down is the direction poetry travels on the page, anyway, and poets have tended to follow their pens. For contrast, the etymology of the word prose means to go forward, generally straight forward, and there’s nothing internal to a sentence that limits its length or sideways nature. Paragraphing arranges ideas logically, but for that one could imagine a codex like an accordion, the folds expanding laterally. Even punctuation isn’t really about organizing or shaping the inherently horizontal character of prose. Periods, commas, and colons regulate the breath, and well-written prose always includes, in its long or short rhythms, a kind of pulmonary function; reaching into these vital rhythms, good prose can, like breathing exercises in yoga, inhabit the visceral life of a reader. Conceivably prose could be written on ribbons hundreds of yards long, winding the reader and testing his lungs in another way, but we bind and store it in books, mainly, so that doesn’t happen. The quotidian tendency of prose is either to satisfy an immediate disposable need or to point beyond itself, toward a distant, receding horizon of information. It’s the écriture of choice for assembling bicycles and analyzing wars, and the difficulty for a writer, the danger, is that his words, failing to capture a cadent, living pulse, will lose meaning in the vastness of other words. If a piece of prose aspires to art, it must close itself off, setting in motion sympathetic vibrations and gaining, as with any enclosure, resonance.

Poetry’s orientation is not primarily horizontal but vertical. It goes across, left to right, but mostly it goes down, top to bottom, and that descent is dictated from within. Though our language for prosody has largely shifted to a discussion of stresses, we still listen for feet and measure in meter the distance a line travels. The syllables in a haiku might be the exception to this idea of poetry’s descent, but you’d lose the stillness in space if all seventeen were strung like clothesline across the page. While a haiku hangs, suspended in air, hexameter hits its beats and heads down, line by line, and it’s easy to imagine an idea of descent and depth coming to a stymied poet by simply staring disconsolately at the page. The etymology of verse means “to turn” or “return,” and if the trick in prose is to overcome its diffuse and vague and ubiquitous presence, the trap for poetry is hermeticism, its tendency toward the occult, the ease with which it turns in on itself and, going down, abandons or forfeits its participation in the upper world. Still, poetry has no choice about its generally chthonic direction. Even a democratic poet like Whitman, resisting hierarchy’s vertical axis with his broad, barbaric yawp, eventually descends. Down is where poetry is, and whatever poetry has to say, whatever it can deliver, is down there too.

In a trope typical of him, at least in this poem, Hugo monkeys with the expected syntactical arrangement, wrenching new emphasis from fairly accessible language; playing with inflection is a way he has of torquing a phrase, and he does it twice in the second stanza. Let me look at the second instance first. The mill “in collapse / for fifty years that won’t fall finally down” gives us the adverb in its most active form. Finally doesn’t idle in an ancillary place, taking up slack because the right verb wasn’t available. In fact, for a word without a verbal form (except the somewhat bureaucratic finalize), finally, as Hugo writes it, is as close as you’re going to get to a sense of the desire inside the downward trajectory of falling. Somehow the down here, the collapse, is being propped up, penultimately supported by an old, useless structure, and finally is the hope or possibility of falling, the fulfillment of fifty years of need. Positioned just above a stanza composed entirely of questions, the line suggests that the mill, slumped in desuetude, must give way before a bottom can be revealed. The end of Pburg (as locals call the town) or history or gray isn’t really the end—there’s something below. But to get to it the landscape’s first got to be leveled, the kilns and the mill razed, the horizontal world abandoned.

“All memory resolves itself in gaze”—this is the second instance of oddly inflected syntax, and it’s an interesting choice. Omitting the expected article creates a slight hitch in the reading, compelling attention, and compresses the word gaze, making it do the work of both noun and verb, mixing stasis and action, fusing space and time—the word is like a pivot, and the entire stanza turns on the phrase, bringing us to a fatal form of memory, an arrested, fixed memory that is now the only thing preventing total collapse, while at the same time offering gaze—gazing—as an action that might release the hold memory has on the horizontal. It’s at this point in the poem that Hugo begins the move toward the salvational hopes of language, of poetry itself. He’s down low, but not low enough yet to find his poem.

It seems to me a poet of Hugo’s skill and knowledge can’t possibly write this line without hearing the allusion to Orpheus. This is the heart of the poem, this is where it is. It happens quickly, reading like a toss-off, without a glance back, but I believe it’s there. Gaze shows up in a similar passage in The Merchant of Venice, also about Orpheus, also about the poet’s power to alter the quality of perception: “Their savage eyes turn’d to a modest gaze / By the sweet power of music: therefore the poet / Did feign that Orpheus . . .” Orpheus, whose lyre is now among the stars, is the figure of the poet and the poet’s work. Nothing can withstand the charms of his music. Beasts are softened and lose their ferocity, stolid oaks move closer just to hear, rocks relax their hardness. Here it’s probably worth mentioning—actually, it’s vital to understanding—that Hugo’s poem sits on top of the pastoral tradition, and certainly could be looked at as a failed bucolic. The poem seems to turn by shorthanding this rich, deep tradition. In Virgil’s Georgics the story of Orpheus shows up strangely, in a treatise on bees, but has the passing character of a fertility myth. That the “green” in Hugo’s poem is only “panoramic” at this point indicates how far from the regenerative power of all these vegetable myths Philipsburg is: there’s no real sustenance in a panorama—or, as they say in Montana, you can’t eat the scenery.

More important to Hugo’s poem than the wide horizontal panorama is the idea of descent and depth implied in the Orpheus myth. Both are orders of vision, but they offer different things. Ovid gives Virgil’s Orpheus a fuller treatment, the one people are familiar with, in which Eurydice, after her wedding to the poet, flees a seducer (Aristaeus, another poet and, not surprisingly, a beekeeper, who will subsequently suffer an apiary disaster) and is bitten by a snake and dies. Orpheus descends into the underworld to reclaim his bride. Along the way a fairy feeds him roasted ants, a flea’s thigh, butterflies’ brains, mites, a rainbow tart, all to be washed down with dewdrops and beer made of barleycorn—indicating, fabulously, the earthy depth of the poet’s descent. In the underworld, as in the upper air, Orpheus sings his grief, and ghosts shed tears, Sisyphus sits on his rock to listen, Ixion’s wheel stops its ceaseless revolving, Tantalus forgets his thirst, and the Furies, just this once, cry. But on his way back to the world, in an exact, cautionary lesson about one of the perils of artistic creation, Orpheus turns around, hoping to reassure himself, and loses his wife, who reaches out for a last embrace as she’s drawn back toward death. Orpheus gives it another shot, but the underworld, whether in Chicago or Hades, is famously unforgiving, and second chances aren’t available. In mourning, Orpheus seems to sicken with ennui, yet plays his lyre, wooing the inanimate world, wresting emotion from the trees and rocks, but eventually, forgoing women and loving boys, he’s torn apart during a Bacchanalia by jealous Thracian maidens, and his severed head floats down the Hebrus, while his lyre, his poetry, is flung to the heavens.

If what distinguishes us from other members of the animal kingdom is speech, then literature—and poetry in particular, being the highest form of locution—is, to put it bluntly, the goal of our species.

—Joseph Brodsky

What’s the deal with a poet who fills an entire stanza, fully a fourth of his poem, with questions? Part of it’s just Hugo’s standard battering style—where a single question might do, he pounds out a whole stanza—but again that style serves the subject. The heavy questions hammer away and demolish the mill that won’t collapse. That Hugo’s prosodic fist is big and blunt only makes it more suitable for the job. Each question—about the persistence of love, the pain of defeat, the scorn preventing desire—undercuts not only the binding failures of Philipsburg but also the poem’s earlier assertions, turning us toward a kind of metacreation. The best way to come at this understanding is through the poem’s back door. Desire in this stanza has an anachronistic, distinctly World War II flavor, with its blondes, booze, and jazz, and you sense Hugo’s own swaggering, wounded self, his own haunting self-doubt, his own town, Seattle, needing to die inside. Suddenly it’s no longer 1907 but 1947, and Hugo is back from the war, reaching down into a pain and hope that’s personal. That’s fine; it’s his poem, after all. This slight historical warp is partly about Hugo’s generous self-effacement, anyway; but it’s also an oblique admission about the stake he has in the poem. In seeking hope for Philipsburg he begins to find hope for himself or, more accurately, for his poem. Here’s the motivation, the stirring of desire, the first turn toward feeling necessary again. In much the same way that the myth of Orpheus elaborates a secondary tale about the act of creation, Hugo too gives us a poem about the making of poetry. The poem offers, somewhat covertly, an allegory of the poet’s soul, caught in the terrifying process of creation. Why would anyone write a poem in this wrecked world? And really, how could they? Massive doubt, failed love, shitty thoughts, empty spirit, a dead history compelling a transfixed vision, these are devastations that might overwhelm and silence anyone; and silence, for a poet, is a prison. It’s where the descent hits bottom, it’s where the poet either faces or does not face all the risks of failed comprehension. It makes sense that Hugo would discover his reason for writing in a stanza so completely expressive of doubt. The critical difference between a poet and a regular citizen is that the poet seeks this realm; it’s where he works, where his office is.

So, why questions? Everything in this stanza could be written using the indicative, flatly observed, or the ragging, hortatory imperative of a coach, urging us on. One answer might be that questions imply an auditor, the presence of another, and a stanza full of them suggests, by reaching out, some break in the isolation. Perhaps the questions are meant to prod an answer, but I kind of don’t think so. Answers are as transient and foolish as we are, and poets generally aren’t in the solution business. In fact, if you’re a poet and you’re going to pose questions, they’d better approach the unanswerable. Why? Is it that only questions without answers are worth asking? Is it that the muse needs courting and doesn’t usually go with know-it-alls and wise guys? Is it that questions salt and preserve life, keeping the mystery fresh? Is it that any descent that hopes to claim our attention and hence a place in the record books is asterisked by answers, as if the poet, cheating, hadn’t really touched bottom? In poetry, is the irritable reaching after answers (or certainties, as Keats put it) paradoxically just a type of doubt, a doubt about poetry itself? If rock bottom, if total bust for a poet is silence, then the questions must be unanswerable, without remedy, to provoke the central event, which is language. Answers are the end of speech, not the beginning, and if language is the main draw in poetry, silence is the occasion for it, the ground of renewal. Questions precede speech; they’re language tensely coiled, expectant.

In the second stanza, the word hatred repeats, and now in the third stanza, it’s ring we hear twice. It’s an excellent, nearly echoic repetition, it rings, but it’s also a curious choice; every connotation I can think of is almost purely positive. Clarity and resonance, calling, summons, proclamations, talk, producing sound, vibration, sonority—all meanings that counter the unanswerable questions, the testing of silence in the stanza. In my reading the aural quality of the word creates tension, making music of a different tenor than the literal subject. My ear hears something my eye doesn’t quite see. The sound of ring rides on the surface of the stanza, separating from it somewhat. Whereas hatred draws us down into the core of the poem, ring begins to lift us out of it. Down deep in this stanza of questions, we hear a ringing, and it becomes possible to understand that Hugo’s questions, their Orphic summons, aren’t calling for an answer; they’re calling for poetry.

How can one write poetry after Auschwitz?

—critic Theodor Adorno

And how can one eat lunch?

—poet Mark Strand

“Say no to yourself ”—if only Orpheus had, if only he’d refused the unsure, doubting, rearward glance, he’d have spent that first night back in the upper air abed with his bride. Instead, his hesitation breaks the lyric charm and condemns Eurydice to death. The temptation, in art as well as life, is to fall back on old forms, to attempt an impossible repetition, giving yourself over to the sort of redundancy that has always been the defining feature of the underworld, where time is either a torment or means nothing because the iterations are endless and unvarying. Hell is crowded not because sinners are commonplace but because incompletion is the norm. Orpheus, descending, charms the underworld, he moves it toward an uncharacteristic stillness and rest, but in ascending, it’s as if his hesitation, his glance back, were suddenly an affliction no different from the thirst of Tantalus or the labor of Sisyphus. Because he looks back, losing his bride, his work remains unfinished, forever, and the sorrow he can’t overcome results in a sort of hypnotic hindsight. “Saying no” is necessary; it too is part of the process of creation. After saying yes to the descent, saying no is how the poet emerges. Perhaps another way of articulating this is to say that a new yes must be found, the courage of the descent sustained until it’s completed. In a poem the future, or the next couple dozen words anyway (which to a poet is the same thing), is the poem. The need is finally aesthetic. Hugo’s final stanza is a return to speech, referenced phrasally throughout: “say no, he says, you tell, you’re talking.” But the return is premised on not looking back, on avoiding the gaze that tempts and paralyzes memory. Unlike Orpheus, the poet here says no and, in true Western fashion, gets the girl, who happens to be slender, with red hair that lights the wall.

It’s not the sort of refusal it might first seem—seemed to me, anyway. It’s not a turning away, an opting out of history, an easy escape. To push the metapoetic reading, the car, that absent term from the first stanza, still runs, as does life, but on this newly accessed level of understanding, I think it’s also fair to say that another of the missing, implied terms is poetry itself. Poetry is the vehicle that broke down and brought Hugo here, to the degrees of gray, but it still runs, and the proof is the poem itself. The poem is what the poet brings back, that’s his fortune, his Eurydice. You can imagine these words lost among broken symbols, dragged off by history, sunk in silence, but that isn’t what we have. Not answers but aesthetic pressure completes the poem. In the end, it doesn’t matter that the light reveals a wall that will likely never come down entirely. “Let us not look for the door, and the way out,” Camus wrote, “anywhere but in the wall against which we are living.” The irony, the slight undertone pulling at Hugo’s last word, tempers the jubilance with a doubt, but suggests that in this prison, shared by all, life is still possible. Fortuna is sometimes depicted wearing a blindfold, and the light in the final line really refers to the act of seeing. It’s about optics more than opportunity. The poem is the light.

Tonight was the Fourth of July, and another order of light was at work, flaring in the sky over these same streets. It was a disorganized display, mostly people in their backyards firing rockets that shot up, burst, fell, and faded, somewhat emptily, in this vast valley. I walked to town because I needed to double-check the streets of Philipsburg and square what I saw with the falling man’s incomprehensible descent. I wanted to think just a little more about Hugo and the place of poetry in the face of terrible things. I stopped by a green house above Main Street where, all last winter, dogs fought over the carcasses of several deer. I remembered the rib cages marbled red and white with blood and fat and the ruts of stained red snow where the warring dogs dragged the bones, but when I passed by tonight I saw the house had been boarded up, the tenant gone in a going that doesn’t really hold much mystery, not here in Philipsburg. What’s another absence, another vacancy? But if this uncelebrated loss means nothing I can’t see how the falling man’s descent acquires true significance either. Consensus isn’t an answer. Mining towns in Montana or Kentucky that have collapsed over the course of a century have suffered a descent as murderous as a moment in New York, but history has hidden those deaths and numbed the witnesses and litanized their loss under the rubric of progress. In the case of Philipsburg, only a poet spoke out, from his own isolation, to say something about the devastating pain.

Still, ruin, nearly as much as a good poem, is strangely enduring. The hills behind Philipsburg are full of things that have failed to remain upright. Poets might not save, but the clichés surrounding September 11 didn’t stop anything either, and in this sense the score, in the game of language, is decisively on the side of poetry. If forced to choose between failures, poetry is probably the better one. The difference between the truth and a cliché is the difference between what we really know and what we’ve all heard about. That diversity is good is a slogan we’ve all heard, but it has expressive limits—it’s not OK to fly jets into office buildings—and so what does it really mean? For me, borrowing from Isaiah Berlin, another writer intimately aware of history, diversity (or plurality) is an answer to the central twentieth-century historical problem of radical subjectivity. Accumulating enough subjectivities—setting them against each other—is as close as we’re going to come to objectivity, and this is why agreement is problematic: What’s the point of being right if it’s only safety in numbers? The history of being right and how wrong it’s turned out to be is a long one. By this measure the terrorists were wrong—such empty holiness is almost too much to bear in mind—but when being right provides comfort, when the sensation of it is pleasant, when it allays anxiety or lends security, then it seems to be doing the job of ignorance. If we’re right, then the nature and quality and burden of being right is our issue. Now it seems time to argue for the tragic or the absurd, for anything that tempers and draws limits. Sometimes contradiction can’t be resolved away and then it becomes the new reality and there’s no way out. The falling man is enormously sad and insignificant; he is everything as well as nothing. The only way into his descent is through our solitude. Patriotism’s just a rag we fly over the silence.

In Mimesis, Erich Auerbach’s book on the representation of reality in Western literature, he talks of the shift from antiquity to a New Testament style of realism. “To be sure,” he writes, “we must not forget that the transformation is here one whose course progresses to somewhere outside of history, to the end of time or to the coincidence of all times, in other words upward, and does not . . . remain on the horizontal plane of historical events.” I wonder, was our understanding of September 11 little more than a Christian homily, an escape from history, a romance secularizing the divine or lifting the legend out of the ruin—is that where it all went? All through the writing of this I thought of Shelley, who at eighteen sent copies of a pamphlet on atheism to every professor at Oxford. He believed a university dedicated to open discussion and the free exchange of ideas would be interested. He was kicked out. Next he went to Ireland, planning to begin a major rehabilitation of all mankind by organizing the Irish into a “society of peace and love,” perhaps a doomed enterprise. Next he was off to Wales, again with a pamphlet, this one called “A Declaration of Rights.” He enclosed copies in dark-green bottles that he sealed with wax and cast into the ocean; other copies he floated aloft, to be blown inland on balloons. Is it reasonable to think Shelley was eternally part of mankind in his solitary foolish hope at sea’s edge? That his solitude was the mark of a deeper, broader inclusion? Or is this just poetic fancy? Watching the fireworks made me wonder. In general I don’t care for activities—fireworks or football or movies—where large groups of people gather and look at the same thing. This is probably just a queerness of temperament. Maybe I don’t like crowds. Regardless, the fireworks rose up, pulsing in our local cosmos. On the way home I stopped to watch the show with some kids who were heaped under blankets while the parents handled the pyrotechnics. Each explosion eclipsed the sky with dazzling colors and froze the onlooking, upturned faces like a strobe. All the kids kept pointing up, the way astonished kids will, as if I might not know where to look.

From The Spirit of History

When gold paint flakes from the arms of sculptures,

When the letter falls out of the book of laws,

Then consciousness is naked as an eye.

When the pages of books fall in fiery scraps

Onto smashed leaves and twisted metal,

The tree of good and evil is stripped bare.

When a wing made of canvas is extinguished

In a potato patch, when steel disintegrates,

Nothing is left but straw and cow dung.

I rolled a cigarette and licked the paper.

Then a match in the little house of my hand.

And why not a tinderbox with a flint?

The wind was blowing. I sat on the road at noon,

Thinking and thinking. Beside me, potatoes.

—Czesław Miłosz

1 Where W = weight, Cd = drag coefficient, r = density, and A = frontal area.