TWO

ENSLAVED WOMEN BECOMING FREEDWOMEN

The Civil War and Reconstruction

IN APRIL 1866, a white man named M. C. Fulton confronted a vexing problem that threatened the viability of his cotton plantation located not far from Augusta, Georgia. During what should have been one of the busiest times of the year—the planting season—the married freedwomen on Fulton’s place refused to go into the fields. Instead, he charged in a letter to a federal agent, these women were “as nearly idle as it is possible for them to be, pretending to spin—knit or something that really amounts to nothing[,] for their husbands have to buy them clothing.” Fulton hoped that he would get a sympathetic hearing from the agent, who represented the United States Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, created by Congress to oversee the transition between slavery and freedom among southern black people. Fulton was both puzzled and alarmed by the freedwomen’s withdrawal from field labor: “Now these women have always been used to working out & it would be far better for them to go to work for reasonable wages & their rations—both in regard to health & in furtherance of their family wellbeing.” By staying at home and having their husbands support them, the planter observed, the women severely diminished his labor supply, and their absence from the fields “must affect to some extent the present crop.” Fulton considered the wives of his male workers “bad examples to those at work . . . [and] often mischief makers,” but he did not judge them in exclusively racialized terms, for, he claimed, “Poor white women . . . have to work—so should all poor people.”

1

It is entirely possible that the bureau agent to whom Fulton sent his letter responded in a way that pleased the planter, by coming to the plantation and giving Fulton’s workers a stern lecture about the virtues of field labor for women and men alike. Many agents aimed to put into practice a view common among white Northerners, whether missionaries, Union military officials, Republican politicians, or transplanted migrants newly arrived in the South. These whites believed that, now that the Civil War had destroyed the institution of slavery, it was essential that black men and women return to the cotton, rice, and sugar fields. As “free” laborers, the former slaves should be bound not by the institution of bondage but by labor contracts negotiated annually with a landlord. According to this view, black women “worked” only when they labored under the watchful eye of a white person in a field, or in a kitchen, but not when they cared for their own families at home. Missing from this equation was the fact that black women’s domestic duties—as caretakers of children and producers of clothing and foodstuffs—nourished and sustained the South’s labor force; in addition, their household labor lessened a landlord’s obligations to supply cash, furnishings, or credit for the goods and services that wives and mothers provided on a routine basis.

For the former slaves, the Civil War destroyed the institution of bondage but opened a new fight for dignity and full citizenship rights. The conflict claimed as many as 700,000 lives; 620,000 northern and southern soldiers died, as did thousands of enslaved laborers forced to toil on the Confederacy’s defenses. The war, initially fought over the preservation of the federal union, gradually evolved into a struggle against slavery and for freedom—the right of all individuals for self-determination. Throughout this era of military and political upheaval, though, black women demonstrated that they would seek to put the interests of their families first. To the extent that they could, freedwomen took control of their own productive energies in ways that thwarted the intentions of planters, the policies of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and the prejudices of white Northerners and Southerners in general. As Fulton fumed, the black wives and mothers stayed at home with their children, working at housekeeping and childcare rather than planting cotton. Yet even bureau agents feared that the “evil of female loaferism”—the preference among wives and mothers to labor on their own terms and to attend to their own households—threatened to subvert the South’s free labor experiment. Like the Irish and French-Canadian immigrant women who toiled in New England textile mills to help support their families, freedwomen were considered by whites exempt from the middle-class feminine ideal of full-time domesticity. Still, the irony did not escape the notice of one Yankee journalist: Of a planter who had come south from the North, employing freedwomen in 1866, the journalist wrote disapprovingly, “An abolitionist making women work in the fields, like beasts of burden—or men!”

2For their part, southern planters could not reconcile themselves to the fact of emancipation; they believed that “free black labor” was a contradiction in terms, that blacks would never work of their own free will. An unpredictable labor situation therefore required any and all measures that would bind the freedpeople body and soul to the southern soil. Black women—at least some of whom had reportedly “retired from the fields” in the mid- 1860s—represented a significant part of the region’s potential workforce in a period when planters’ fears about low agricultural productivity reached almost hysterical proportions. Ultimately, southern whites embraced an authoritarian labor system, alternately accommodating, cajoling, and brutalizing the people whom they had once claimed to care for and know so well. Thus by the end of the Civil War, it was clear that the victorious Yankees and the vanquished Confederates agreed on very little when it came to rebuilding the war-torn South; but one assumption they did share was that black wives and mothers should continue to toil under the supervision of whites.

3Freed blacks resisted both the northern work ethic and the southern system of neoslavery: “Those appear most thriving and happy who are at work for themselves,” noted one perceptive observer. The full import of their preference for family-based systems of labor organization over gang labor becomes apparent when viewed in a national context. The industrial North was increasingly coming to rely on workers who had yielded to employers all power over their working conditions. In contrast, sharecropping husbands and wives retained a minimal amount of control over their own labor and that of their children on both a daily and seasonal basis. Furthermore, the sharecropping system enabled mothers to divide their time between field- and housework in a way that reflected a family’s needs. The system also removed wives and daughters from the reach of lacivious white supervisors. Here then were tangible benefits of freedom that could not be reckoned in financial terms.

4As workers or potential workers, freedpeople assumed the roles of political actors in an era marked by clashes over land, labor, and political rights. Because the former slaves preferred to labor in kin groups rather than gangs, the black family of necessity became enmeshed in larger questions about justice on the southern countryside; indeed, the relations between (working) husbands and (“nonworking”) wives, and between parents and school-age children became subjects of larger debates about southern economic recovery and the status of freedpeople in general. Therefore it is difficult to disentangle family life—and the choices of, and constraints upon, black women in particular—from partisan political contests that pit Republicans against Democrats in the postbellum South. Although black women did not gain the right to vote when their menfolk did in 1867, they nevertheless participated in the great political debates of the day in their roles as workers and as fully engaged members of freed communities.

Emancipation was not a gift bestowed upon passive slaves by Union soldiers or presidential proclamation; rather, it was a process by which black people ceased to labor for their masters and sought instead to provide directly for one another. Control over one’s labor and one’s family life represented a dual gauge by which freedpeople measured true freedom. Blacks sought to weld kin and work relations into a single unit of economic and social welfare so that women could be wives and mothers first and laundresses and cotton-pickers second. The experiences of black women during these years revealed both the strength of old imperatives and the significance of new ones; in this regard their story mirrors on a personal level the larger drama of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

IN PURSUIT OF FREEDOM

The institution of slavery disintegrated gradually. It cracked under the weight of Confederate preparations for war soon after cannons fired on Fort Sumter in April 1861, and it crumbled—in some parts of the South many years after the Confederate surrender—when the former slaves were finally free to decide whether to leave or remain on their master’s plantation. The effects of military defense strategy on the lives of blacks varied according to time and place; before the war’s end a combination of factors based on circumstance and personal initiative opened the way to freedom for many, but often slowly, and only by degrees. Throughout the war, many enslaved workers remained alert to the dangers and the opportunities posed by military conflict and social upheaval. For women, the welfare of their children was often the primary consideration in determining an appropriate course of action once they confronted, or themselves created, a moment ripe with possibilities.

5Three individual cases suggest the varying states of awareness and choice that could shape the decisions of enslaved women during this period of violence and uncertainty. In 1862 a seventy-year-old Georgia bondswoman engineered a dramatic escape for herself and her twenty-two children and grandchildren. The group floated forty miles down the Savannah River on a flatboat and finally found refuge on a federal vessel. In contrast, Hannah Davidson recalled many years later that she and the other slaves on a Kentucky plantation lived in such rural isolation—and under such tyranny—that they remained bound to a white man until the mid-1880s: “We didn’t even know we were free,” she said. Yet Rosaline Rogers, thirty-eight years old at the war’s end and mother of fourteen children, kept her family together on her master’s Tennessee plantation, even after she was free to leave: “I was given my choice of staying on the same plantation, working on shares, or taking my family away, letting them out [to work in return] for their food and clothes. I decided to stay on that way; I could have my children with me.” But, she added, the arrangement was far from satisfactory, for her children “were not allowed to go to school, they were taught only to work.”

6The logic of resistance proceeded apace on plantations all over the South as slaveholders became increasingly preoccupied with the Confederacy’s declining military fortunes. On a Mississippi plantation, Dora Franks overheard her master and mistress discussing the horror of an impending Yankee victory. The very thought of it made the white woman “feel lak jumpin’ in de well,” but, Dora Franks declared, “from dat minute I started prayin’ for freedom. All de res’ of de women done de same.” Enslaved workers did not have to keep apprised of rebel maneuvers on the battleground to take advantage of novel situations produced by an absent master, a greenhorn overseer, or a nervous mistress uncertain how to maintain the upper hand. Under these conditions, black women, men, and children slowed their work pace to a crawl. “Awkward,” “inefficient,” “lazy,” “erratic,” “ungovernable,” and “slack” (according to exasperated whites), they left weeds in the cotton fields, burned the evening’s supper to a crisp, and let the cows trample the corn.

7Eliza Andrews, daughter of a prominent Georgia judge and slaveholder, expressed disgust when, a few days before the Confederacy’s surrender, Lizzie, the family cook, stated emphatically that she would not be willing to prepare a meal “fur Jesus Christ to-day,” let alone for two of her mistress’s special friends. Aunt Lizzie and other enslaved women seemed to be fully aware of the effect their “insolence” had on mistresses “who had not been taught to work and who thought it beneath their standing to soil their hands.” Safely behind Union lines, a Tennessee refugee told of an apocryphal encounter between her mistress and General Ulysses S. Grant: “Den she went back to the general, an’ begged an’ cried, and hel’ out her han’s, and say, ‘General dese han’s never was in dough—I never made a cake o’ bread in my life; please let me have my cook!’” On some plantations, the startlingly open recalcitrance of female slaves seemed to portend greater evils, as white parents and children whispered in hushed tones about faithful old mammies who might spy for the Yankees and cooks who could “burn us out” or “slip up and stick any of us in the back.”

8Their chains loosened by the distractions of war, many enslaved men and women challenged the physical and emotional resolve of whites in authority. For the vast majority, however, the war itself only intensified their hardships. As the Confederacy directed more of its resources and manpower toward the defense effort, food supplies became scarce throughout the region. Black men and women registered the effects of war when they were forced to abandoned familiar routines and grow corn instead of cotton. Planters and local government officials, anxious in the midst of black (and even white) rebels on their own soil and uncertain about the future of their new nation, reacted brutally to isolated cases of real and imagined insubordination. The owner of a Georgia coastal plantation was so infuriated by the number of his slaves who had fled to Union lines that he took special precautions to hold on to his prized cook; he bound her feet in iron stocks so that “she had to drag herself around her kitchen all day, and at night she was locked into the corn-house.” Refugees arrived in Union camps with fresh scars on their backs told of masters and mistresses unleashing their bitterness on “blobber-mouth niggers [who] done cause a war.”

9During wartime the responsibility for the care of children, the ill, and the elderly devolved upon enslaved women to an even greater extent than had been the case during the antebellum period. The services of white physicians were diverted away from plantations; before the war they had tried to keep the enslaved labor force “sound,” and now they must attend to wounded and dying soldiers on battlefields and in hospitals. Black women healers stepped into the breach, utilizing their own folk methods and medicines to minister to the ill in the quarters.

10Confederate military mobilization and the lure of Union lines wreaked havoc on the already fragile ties that held families together. Efforts to restrict slave mobility prevented husbands from visiting their “broad” wives on a regular basis and discouraged cross-plantation marriages in general. Confederate impressment policies primarily affected enslaved men, who were put to work on military construction projects and in army camps, factories, and hospitals. The practice of “refugeeing” highly valued workers to the interior or to another state also meant that the strongest, healthiest men were taken away from plantation wives and children. On a western North Carolina plantation, a Confederate mandate that planters help feed the troops placed almost unbearable demands on young, old, and female enslaved workers, now forced to fill the places of black men impressed by the army. The effects of both refugeeing and impressments transformed slave communities in southwest Georgia, with long-standing members forcibly transported to Savannah and newcomers crowding plantations. One former bondsman later recalled that, when he was thirteen years old, his wartime master “put so much work on me, I could not do it; chopping & hauling wood and lumber logs.” Some husbands and fathers made a bold bid for freedom, in some cases returning to free loved ones and spirit them away to safety—or at least to Union territory. Many freedwomen struggled to provide for their dependents while facing new and harsh demands from whites. These challenges tested the limits of a newfound freedom for wives and mothers.

11At times in different parts of the South, the approaching Union army provided black workers with both an opportunity and an incentive to flee from their masters. Soon after the Union forces took control of the South Carolina Sea Islands, Elizabeth Botume, a newly arrived northern teacher, observed a refugee mother and her three children hurrying toward a government steamer: “A huge negress was seen striding along with her hominy pot, in which was a live chicken, poised on her head. One child was on her back with its arms tightly clasped around her neck, and its feet about her waist, and under each arm was a smaller child. Her apron was tucked up in front, evidently filled with articles of clothing. Her feet were bare, and in her mouth was a short clay pipe. A poor little yellow dog ran by her side, and a half-grown pig trotted on before.” From other parts of the South came similar descriptions of women travelers balancing bundles on their heads and children on their backs. These miniature caravans exemplified the difficulties faced by single mothers who ran away and sought protection behind Union lines.

12To women like the Louisiana mother who brought her dead child (“shot by her pursuing master”) into a Yankee army camp “to be buried, as she said,

free,” Union territory symbolized the end of an old life and the beginning of a new one. But it was an inauspicious beginning. Crowded together, often lacking food, shelter, and medicine, these human “contraband of war” lived a wretched existence. Moreover, in 1863 the refugee settlements—and virtually any areas under federal control—became targets for northern military officials seeking black male conscripts. Black men wanted to defend their families and fight for freedom, and almost a quarter of a million served the Union war effort in some formal capacity—half as soldiers, the rest as laborers, teamsters, craftsmen, and servants. More than 110,000 black men from the Confederate states alone—14 percent of the black male population aged eighteen to forty-five—fought with the Union army. However, the violent wrenching of draftees from their wives and children caused great resentment among the refugees, especially those in the Georgia and South Carolina low country in the spring of 1863. The women of one camp, wrote Elizabeth Botume, “were proud of volunteers, but a draft was like an ignominious seizure.” The scene in another one “raided” by Yankee soldiers hardly resembled a haven for the oppressed; wives “were crying bitterly, some looked angry and revengeful, but there was more grief than anything else.”

13Whether southern black men volunteered for or were pressed into Union military service, the well-being of their families remained a constant source of anxiety for them. Wives and children who remained behind in Confederate territory on their masters’ plantation, and even some of those who belonged to owners sympathetic to the northern cause, bore the brunt of white men’s anger as the peculiar “southern way of life” began to recede. In Kentucky, Frances Johnson, whose husband was a Union soldier, reported that in 1864 her master had told her, “All the ‘niggers’ did mighty wrong in joining the Army.” One day the following spring, she recalled, “My master’s son . . . whipped me severely on my refusing to do some work for him which I was not in a condition to perform. He beat me in the presence of his father who told him [the son] to ‘buck me and give me a thousand’ meaning thereby a thousand lashes.” The next day this mother of three managed to flee with her children and find refuge with her sister in nearby Lexington. In another case a Missouri slave woman wrote to her soldier husband, “They are treating me worse and worse every day. Our child cries for you,” but added, “do not fret too much for me for it wont be long before I will be free and then all we make will be ours.” In a Union camp in Virginia, a Union officer observed that black soldiers remained aware of the abuse suffered by their wives still enslaved: “A large number of them have families still remaining in servitude, who are most shamefully and inhumanely treated by their masters in consequence of their husbands having enlisted in the union army.” Accounts like these impelled black soldiers to demand that the federal government provide their loved ones with some form of protection.

14In an effort to stay together and escape the vengeance of southern whites, some families followed their menfolk to the front lines. However, soldiers’ wives, denounced as prostitutes and “idle, lazy vagrants” by military officials, found that the army camps offered little in the way of refuge from callousness and abuse. The payment of soldiers’ wages was a notoriously slow and unpredictable process, leaving mothers with responsibility for the full support of their children. The elaborate application procedures discouraged even qualified women from seeking aid from the Army Quartermaster Department. A few wives sought jobs as laundresses and cooks in and around the camps, but gainful employment was not easy to come by during such chaotic times. Women fugitives found work in Union hospitals, but as nurses they were rarely granted the status or wages—and later pensions—accorded white women doing similar kinds of work. Meanwhile, not only did many families lack basic creature comforts in the form of adequate clothing and shelter; they were at times deprived of what little they did have by Union officers who felt that the presence of black wives impaired the military efficiency of their husbands. At Camp Nelson, Kentucky, in late 1864, white soldiers leveled the makeshift shantytown erected by black women to house their children and left four hundred persons homeless in bitterly cold weather. Such was the treatment accorded the kin of “soldiers who were even then in the field fighting for that Government which was causing all this suffering to their people.”

15Although many women had no choice but to seek food and safety from northern troops, often with deeply disappointing or even horrific results, others managed to attain relative freedom from white interference and remain on or near their old home sites. In areas where whites had fled and large numbers of black men had marched—or been marched off—with the Union army, women of all ages grew crops and cared for each other. For example, several hundred women from the Combahee River region of South Carolina made up a small colony unto themselves in a Sea Island settlement. They prided themselves on their special handicrafts sent to their men “wid Mon’gomery’s boys in de regiment”: gloves and stockings made from “coarse yarn spun in a tin basin and knitted on reed, cut in the swamps.” Together with men and women from other areas, the “Combees” cultivated cotton and potato patches, gathered ground nuts, minded the children, and nursed the ill.

16Such demonstrations of self-sufficiency amounted to political statements of defiance and determination among black fugitives. Indeed, within the context of armed conflict, news of a group of black men and women peacefully tilling the soil could strike fear in the hearts of low-country planters; such was the case when black refugees and fugitives established a colony on St. Simons Island, off the coast of Georgia, in the summer of 1862. Union officials initially encouraged the effort, which they believed could serve to provision Union troops in the area; wrote Commander S. W. Godon (aboard the

Mohican in St. Simons Sound) to his superior, Flag-Officer DuPont: “Such a colony, properly managed, would do much good.” And indeed the colonists set about growing crops and marketing foodstuffs and their own services to seamen in the area. Noted DuPont of the “contrabands”: they “work for us in many ways and are very useful, and we pay them ten dollars a month and a ration.” A list of “tariff of prices” charged to customers reveals black people

qua provisioners for the Union navy and entrepreneurs in their own right. The tariff also suggests the eagerness among former slaves to put a specific price on goods and services they had provided their masters free of cost, and under duress. Among the foodstuffs they sold were milk (four cents a quart), corn (five cents per dozen), terrapins (ten cents each), watermelons (ten to fifteen cents each), chicken eggs (twelve cents per dozen), turtle eggs (five cents per dozen), as well as okra, beans, whortleberries, cantaloupes, and squash. The St. Simons colonists also raised chickens, trapped rabbits, and caught shrimp and fish, all of which they sold to seamen. Black laundresses charged fifty cents per dozen articles of clothing (“when soap and starch furnished”). By midsummer the colony consisted of six hundred men, women, and children.

17At the same time, the significance of St. Simons went beyond the obvious mutual advantage to both parties, buyers and sellers of goods and services. The colonists chose a leader from among themselves, Charles O’Neal; he was later killed in a skirmish with rebels on the island. In their attempts to establish a self-sufficient settlement, the colonists also brought together family members separated during slavery and the war. A Union chaplain, the Reverend Mansfield French, solemnized long-standing relationships as legal marriages, and presided over baptism ceremonies that included not only nuclear families but also “children presented by relatives or strangers, the parents being sold.” Susie Baker, a literate fourteen-year-old refugee from Savannah, started a school on the island: “I had about forty children to teach, besides a number of adults who came to me nights, all of them so eager to learn to read, to read above anything else.” The Reverend French made periodic appearances in the school to lecture the pupils on “Boston and the North,” among other subjects.

18Yet the colonists’ industriousness did not always mesh with federal officials’ notions of black people’s labor. The former slaves desired to control their own productive energies; they resisted orders from white men, and they concentrated their efforts on subsistence activities and not on cultivating staple crops such as cotton. DuPont acknowledged the blacks’ “great dislike to do the work they have been accustomed to—that seems to make their condition the same as before. They will sit up all night and fish and catch crabs and go and catch horses and wild cattle and cross to the mainland on sculls and go and get corn and so on”; but they sought to free themselves of the enforced pace of fieldwork. This impulse— toward self-direction and away from slavery—foreshadowed the development of freedpeople’s settlements throughout the South after the war.

19For women who had accumulated modest amounts of household goods and other forms of property before or during the war, their first encounter with Union troops was hardly reassuring. Toward the end of the conflict, the federal armies lived off the land and appropriated food, clothing, household goods, and mules and horses from black and white Southerners alike. Into Yankee saddlebags and stomachs went the fruits of black people’s labor for themselves. Rebecca Smith, a free woman of color in Beaufort County, South Carolina, lost pots, pans, and bedding to Union troops. When Sherman swept through Georgia from Atlanta to Savannah in late 1864, he authorized his troops, and specially appointed “bummers,” to raid homesteads of all kinds in search of the provisions needed to keep his army of 60,000 well fed with the stores of honey, lard, rice, and chickens accumulated by enslaved workers along his route. Among the objects of Sherman’s rapacious bummers were the black women of Savannah who had profited from wartime demands for lodging and food. Together with her partner, Moses Stikes, Binah Butler cultivated a seven-acre garden in the city; they paid their respective masters a certain amount for the privilege. Together they “worked there two years raising all kinds of Garden

truck for the market” and selling chickens. They also managed to stockpile fifty bushels of potatoes and 2,500 pounds of fodder and hay.

20The end of the war signaled the first chance for large numbers of blacks to abandon the slave quarters as a demonstration of liberty. Asked why she wanted to move off her master’s South Carolina plantation, the former slave Patience responded in a manner that belied her name: “I must go, if I stay here I’ll never know I’m free.” An elderly black woman turned her back on the relative comfort of her mistress’s home and chose to live in a small village of freed people near Greensboro, Georgia, so that she could, in her words,

“Joy my freedom! ” These and other freedwomen acted decisively to escape the confinement of the place where they had lived as enslaved laborers. In the process they deprived the white South of a large part of its black labor supply.

21Amid the dislocation of civil war, then, black women’s priorities and obligations coalesced into a single purpose: to escape from the oppression of slavery while keeping their families intact. Variations on this theme recurred throughout the South, as individual women, in concert with their kin, composed their own hymns to emancipation more or less unfettered by the vicissitudes of war. Though the black family suffered a series of disruptions provoked by Confederates and Yankees alike, it emerged as a strong and vital institution once the conflict had ended. The destiny of freedwomen in the postbellum period would be inextricably linked to that of their freed families.

BLACK WOMEN AS “FREE LABORERS,” 1865-1870

Soon after he assumed the position of assistant commissioner of the Louisiana Freedmen’s Bureau in 1865, Thomas W. Conway stated his policy regarding families of southern black Union soldiers. The northern federal agent found distressing the reports that former slaveowners near Port Hudson had, “at their pleasure,” turned freedwomen and children off plantations “and [kept] their pigs chickens and cooking utensils and [left] them on the levee a week in a starving condition.” Still, he remained firmly convinced that the government should not extend aid to soldiers’ dependents; Conway wanted the “colored Soldiers and their families . . . to be treated like and expected to take care of themselves as white Soldiers and their families in the north.” Moreover, the commissioner observed, the bureau “could not compel the planters to retain those women if their husbands were not on the place, unless contracts had been made with them.” He appreciated the sacrifices that black soldiers had made for the “Noble Republic,” but with their wages from military service (no matter how meager or unpredictable), “and the amount which can be earned by an industrious woman,” he saw no reason why their families could not “be maintained in at least a comfortable manner.” The freed people needed only to demonstrate “a little economy and industry” and they would become self-supporting.

22Viewing emancipation through a prism of their own self-interest, whether defined in ideological or material terms, whites in general showed a profound lack of understanding about the values and priorities that animated black men and women during the era of the Civil War. When Mobile came under Union control, a white woman, Ann Quigley, scornfully noted a dramatic change in the demeanor of black workers: “The insolence of servants is intolerable & those who have been treated with the greatest kindness, are the most insolent & ungrateful. . . . They have become so worthless, so demoralized.”

23During the first fearful months of freedom, black families searching for loved ones and those seeking refuge in the city came in for much bitter criticism from whites who claimed the former slaves were wandering around the countryside aimlessly, avoiding work and creating havoc. Gradually many freedpeople returned to the general area where they had been enslaved in an effort to provide for themselves, and to claim, if possible, the lands upon which their forebears had labored and died. The degree to which the antebellum elite remained in power varied throughout the South. Nevertheless, the failure of the federal government to institute a comprehensive land confiscation and redistribution program, combined with southern whites’ systematic refusal to sell property or extend credit to the former slaves, meant that the majority of blacks would remain economically dependent upon the group of people (if not the individuals) whom they had served as slaves. The extent of black migration out of the South during this period was negligible—and understandable, considering the lack of job opportunities for blacks elsewhere in the country. Most freedpeople remained in the vicinity of their enslavement; the proximity of kin groupings helped to determine precisely where they would settle.

Many whites felt that blacks as a “race” would gradually die out as result of their inability to care for themselves and work independently of the slaveholder’s whip. The eagerness with which blacks initially fled the plantations convinced these white men that only “Black Laws” limiting their freedom of movement would ensure a stable labor force. The Yankees’ vision of a free labor market, in which individual blacks used their wits to strike a favorable bargain with a prospective employer, struck the former Confederates as a ludicrous idea and an impossible objective.

24When it came to reconstructing southern society, Northerners were not all of the same stripe. But Republicans, and those in positions of political authority generally, tended to equate freedom with the opportunity to reap the profits from one’s own toil, regardless of whether one owned land or worked for wages on someone else’s land. Yankees conceived of the contract labor system as an innovation that would ensure the production of cotton necessary for the New England textile industry, and protect blacks against unbridled exploitation at the hands of their former masters. If a person did not like the terms or treatment accorded by an employer, he or she should look for work elsewhere, thereby (it was assumed) encouraging die-hard rebels to conform to enlightened labor practices. In time, after a thrifty household had accumulated a little cash, it could buy its own land and become part of the independent yeomanry. To this end northern Republicans established the Freedmen’s Bureau, which oversaw contract negotiations between the former slaves and their new masters.

25The contract system was premised on the assumption that freedpeople would embrace gainful employment out of economic necessity if for no other reason. Still, the presumed baneful effects of generations of enslavement on blacks’ moral character led Bureau Commissioner Oliver O. Howard to express the pious hope that, initially, “wholesome compulsion” would lead to “larger independence” for the masses. “Compulsion” came in a variety of shapes and sizes. For the Yankee general stationed in Richmond and determined to get the families of black soldiers off federal rations, it amounted to “hiring out” unemployed women or creating jobs for them in the form of “a grand

general washing establishment for the city, where clothing of any one will be washed gratis.” He suggested that “a little hard work and confinement will soon induce them to find employment, and the ultra philanthropists will not be shocked.” In another case, after just a few months in the Mississippi Valley, one northern planter concluded that “many negro women

require whipping.” Indeed, even many “ultra philanthropists,” including the northern teachers commissioned to minister to the freed blacks, believed that hard manual labor under the supervision of whites would refresh the souls of individual black women and men even as it restored the postwar southern economy.

26The bureau’s annual contract system proved ill-suited as a means for the former slaves to achieve true freedom. Workers were required to sign up for a year’s stint on January 1, and to remain with the same employer until December 31. Yet the calendar year did not jibe with the growing season, with its busy weeks in the spring and late fall; at dispute then were the slack periods when black families wished to work on their own, while planters were demanding that they repair fences, clear brush, and perform other duties not directly related to crop cultivation. Contracts often stipulated that families were forbidden from keeping chickens or tending gardens, an effort to render the household completely dependent on the supplies extended on credit by the landlord. Northern officials assumed that workers would exercise their right to leave a place when the contract expired, failing to anticipate that many landlords kept their workers in debt from one year to another, forcing them at gunpoint to labor to pay off the debt. Even families that did leave a plantation at “reckoning time” found that other employers down the road instituted the same exploitative labor policies. The Northerners’ idea that planters would compete for workers through fair and reasonable working conditions and wage practices found no favor, or practical application, among white landowners.

If few enslaved women ever had the luxury of choosing between different kinds of work, freedwomen with children found that economic necessity bred its own kind of slavery. Their only choice was to take whatever work was available—and that was not much. Despite the paternalistic rhetoric of the antebellum period, planters quickly adjusted to a postwar calculus based on postwar financial considerations. Gone were the professions of concern for all the black members of “our family,” including nonproductive workers such as the very young and the very old. In their place were demands only for the able-bodied, forcing freed mothers to make agonizing choices. These dilemmas surfaced during the war, and continued well after it. In Mississippi, the enslaved domestic Elsy had to choose between living with her husband, who lacked the means to support her and their four children, and with her mistress. She decided to remain with the white woman and earn wages, prompting her husband to complain that “she waits on the [mistress] and none of the others do; that she behaves as if she was not free.” For understandable reasons, women who had to support their children were more likely to remain on a plantation after the war compared to those women who could count on the support of their husbands or other family members.

27Field-hands and domestic servants who decided to stay on or return to their master’s plantation needed the children’s help to make ends meet; at times it seemed as if only seasoned cotton-pickers would be able to eat. In May 1866, “a worn, weary woman with 11 children, and another, with three,” spent ten days in the forest near Columbus, Georgia, before entering the city to seek assistance. “We was driv off, Misses, kase wese no account with our childer,” they told two sympathetic northern teachers. In like manner, a mother of five, evicted from a North Carolina farm by a white man who declared their “keep” would cost him more than they could earn, responded that “it seemed like it was mighty hard; she’d been made free, and it did appear as if thar must be something more comin’.” Prized by antebellum planters as reproducers of the enslaved workforce, black women with children were now reviled as parasites, a drain on the resources of the postbellum plantation.

28Virtually all black women had to contend with the problem of finding and keeping a job and then depending upon white employers for payment. The largest single category of grievances initiated by black women under the Freedmen’s Bureau “complaint” procedures concerned nonpayment of wages, indicating that many workers were routinely—and ruthlessly—defrauded of the small amounts they had earned and then “run off the place.” (See Appendix A.) Few southern planters had reserves of cash on hand after the war, and so they “fulfilled” commitments to their employees by charging prices for supplies so exorbitant that workers were lucky if they ended the year even, rather than indebted to their employer. Presley George Sr., near Greensboro, North Carolina, made a convenient settlement with two of his field-hands, Puss and Polly, for their performance as free laborers during 1865. Here are their final accounts:

| Due Presley George by Polly: |

| For 4¾ cuts wool @ 75¢/cut | $3.50 |

| 22 yds. cloth @ 50¢/yd. | 11.00 |

| 5 yds. thread @ 50¢/yd. | 2.50 |

| Boarding one child (who didn’t work) for 5 months | 12.00 |

| 10 bushels corn @ $1.00/bushel | 10.00 |

| 30 bushels corn @ $1.00/bushel | 30.00 |

| TOTAL | $69.00 |

| Due Polly by Presley George: |

| For 3 months’ work “by self” @ $4.00/month | $12.00 |

| For 4 months’ work by son Peter @ $8.00/month | 32.00 |

| For 4 months’ work by son Burrell @ $4.00/month | 16.00 |

| For 4 months’ work by daughter Siller @ $2.25/month | 9.00 |

| TOTAL | $69.00 |

| Due Presley George by Puss: |

| For 6 yds. striped cloth @ 50¢/yd. | $3.00 |

| 1¾ cuts wool @ 75¢/cut | 1.25 |

| 10 bushels corn @ $1.00/bushel | 10.00 |

| TOTAL | $14.25 |

| Due Puss by Presley George: |

| For 4 months’ work @ $3.50/month | $14.0029 |

Polly and Puss had signed contracts with Presley George under the bureau’s wage labor agreement system, but that act of faith on their part hardly guaranteed them a living wage, or even any cash at all. The bureau recommended that cotton field-hands receive a monthly wage ($10 to $12 per month for adult men, $8 for women) and that employers refrain from using physical force as a means of discipline. However, thousands of freed blacks contracted for rations, clothing, and shelter only, especially during the period from 1865 to 1867. Employers retained unlimited authority in using various forms of punishment, physical and otherwise, and felt free to disregard the agreements at the first sign of recalcitrance on the part of their laborers. In these contracts, prohibitions against movement on and off the plantation were routine; blacks had to promise to “have no stragling about their houses and not to be strowling about at night,” and they needed written permission to go into town or visit relatives nearby. The bureau tolerated and even in most cases approved these harsh and restrictive terms. As the teacher Laura Towne noted, “enforcement” of the contracts usually meant ensuring that “the blacks don’t break a contract and [then] compelling them to submit cheerfully if the whites do.”

30The bureau arranged for the resolution of contract disputes, and agents often made unilateral judgments when one party sued with a complaint; in other cases arbitration boards or military courts handed down decisions. Word traveled quickly among whites when officials particularly sympathetic to planters’ interests opened their offices for business. For example, Agent Charles Rauschenberg, stationed in Cuthbert, Georgia, had little free time once he responded energetically to charges like the one Ivey White lodged against his field-hand Angeline Sealy: “Complains that she is lazy and does not pick more than 35 to 40 lbs. cotton per day.” The verdict: “Charge sustained—receives a lecture on her duties and is told that if she does not average from 75-100 lbs. cotton per day that a deduction will be made from her wages.” Most Northerners in positions of formal authority during the Reconstruction period detested southern planters as Confederate rebels but empathized with them as fledgling capitalists attempting to transition to a “free labor” contract system. Moreover, few Union officials were inclined to believe that freedwomen as a group should contribute anything less than their full muscle power to the rebuilding of the region’s economic system.

31High rates of geographical mobility (as blacks moved about the southern countryside, in and out of towns, and to a lesser extent, to the southwestern part of the region) make it difficult to pinpoint with any precision the number of black women in specific kinds of jobs immediately after the war. Charlie Moses’s mother moved the family from one Louisiana farm to another in search of work; “We jus’ travelled all over from one place to another,” he recalled. Freedwomen accepted any work they could find; in Columbia, South Carolina, they took the places of mules and turned screws to press cotton. The seasonal nature of agricultural labor meant that families often had to locate new sources of employment. When the cotton-picking season ended, for instance, Mingo White and his mother cut and hauled wood on an Alabama plantation. Many women had no choice but to continue working as field-hands cultivating staple crops for white landowners, their former masters.

32Other freedwomen relied on their cooking, gardening, dairying, and poultry-raising skills in an effort to make money as petty tradeswomen. In Aiken, South Carolina, a roving Yankee newspaper correspondent noted with approval that a black woman given fifty cents one day had appeared the next selling cakes and fresh fruit purchased with the money. Some women peddled berries, chickens, eggs, and vegetables along the road and in towns. During the difficult winter of 1865, a Charleston open-air market was “presided over” by “eyesnapping ‘Aunties’” who sold their produce from small stalls.

33Others tried to turn their special talents into a secure means of making a living. Nevertheless, former slaves were too poor to pay much for the services of midwives and seamstresses, and whites at times did not pay at all. Most freedwomen had to piece together seasonal or part-time labor in any case. Even the small number of literate women who aspired to teaching, an estimated half of all teachers of the freedpeople in 1868, had to rely on the fortunes of local black communities, most of which were unable to support a school on a regular basis. Susie Baker King (married to a Civil War veteran) taught pupils in Savannah soon after the war; she and other independent instructors could hardly compete with a free school operated by a northern freedmen’s aid society, the American Missionary Association (AMA). As a result, she was eventually forced from teaching into domestic service. A tiny number of teachers did qualify for aid from the Freedmen’s Bureau or a private group like the AMA. In Georgia between 1865 and 1870, for example, perhaps seventy-five freedwomen received a modest salary for at least a few months from a northern source. However, New Englanders eager to help the cause of freedpeople’s education preferred to commission white teachers from the northern and midwestern states.

34Although blacks remained largely dependent upon whites for employment and supplies, strikes and other forms of collective action among workers began to surface soon after the Yankee invasion of the South. During the busy harvest season in the fall of 1862, female field-hands on a Louisiana sugar plantation in Union-occupied territory engaged in a slow-down and then refused to work at all until the white landowner met their demand for wages. The men on the plantation also struck within a week. The planter, fearful that his entire crop would be lost if it were not cut and processed immediately, finally agreed to pay them. And in 1866, the “colored washerwomen” of Jackson, Mississippi, organized themselves and established a price code for their services. Though the strike in June of that year was unsuccessful, it suggested the potential inherent in group solidarity where black women predominated in an industry—in this case, laundry work.

35Slowly and grudgingly some whites began to learn a basic lesson of Reconstruction: Blacks’ attitudes toward work depended on the extent to which they were free from white supervision. Edward S. Philbrick, a shrewd Yankee planter masquerading as a missionary on the South Carolina Sea Islands, marveled in March 1862 over the ability of former slaves to organize themselves and prepare hundreds of acres for planting cotton “without a white man near them.” (Under the same conditions the Irish would not have shown as much initiative, he thought.) Frances Butler, daughter of the renowned actress and abolitionist Fanny Kemble but more similar in temperament to her slaveholding father, Pierce, returned to the family’s Georgia estate in 1866. The young woman soon discovered that the elderly freedpeople were “far too old and infirm to work for me, but once let them get a bit of ground of their own given to them, and they become quite young and strong again.” She had discovered that the aged Charity—“who represented herself as unable to move”—walked six miles almost every day to sell eggs (from her own chickens) on a neighboring plantation. And there were other women who derived newfound physical strength from self-reliance. A woman helping to “list” her family’s small plot of land on James Island, South Carolina, startled a northern observer with her “vehement” declaration: “I can plough land same as a hoss. Wid dese hands I raise cotton dis year, buy two hosses!”

36In their desire for household self-determination, blacks defied bureau agents and northern and southern planters alike, challenging both the northern ethos of individualism and the southern imperative of staple crop agriculture. And ultimately the annual contract system failed to yield the benefits anticipated by either group of whites. Northerners underestimated the extent to which black people would be prevented from accumulating cash and acquiring property. On the other hand, Southerners had not counted on the leverage wielded by workers determined to pry concessions out of them in the form of days off and garden privileges, and to press their own advantage during times of labor shortages. Some of this leverage assumed the form of meaningful political power at the local and state levels; for example, South Carolina rice workers (as members of the Republican Party) played a vital role in that state’s political process until Reconstruction ended in 1877. In making certain decisions about how family labor was to be organized, black people not only broke with the past in defiance of the white South, they also rejected a future of materialistic individualism in opposition to the white, middle-class North.

37

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF BLACK FAMILY AND COMMUNITY LIFE IN THE POSTWAR PERIOD

The Northerners’ hope that black workers would be able to pursue their interests as individuals did not take into account the strong family ties that bound black households together. More specifically, although black women constituted a sizable proportion of the region’s labor force, their obligations to their husbands and children and kin took priority over any form of personal self-seeking. For most black women, then, freedom had very little to do with individual opportunity or independence in the modern sense. Rather, freedom had meaning primarily in a family context. The institution of slavery had posed a constant threat to the stability of family relationships; after emancipation these relationships became solidified, though the sanctity of family life continued to come under pressure from the larger white society. Freedwomen derived emotional fulfillment and a newfound sense of pride from their roles as wives and mothers. Only at home could they exercise a measure of control over their own lives and those of their husbands and children and impose a semblance of order on the physical world.

At the same time, black women engaged in protopolitical activity when they withdrew from fieldwork, protested exploitation at the hands of employers, and lent their support to grassroots campaigns on behalf of landownership and civil rights. They remained deeply engaged in the momentous question of the day—the true meaning of freedom. That question resonated in the cotton and rice fields of the South, and in the kitchens of white women, no less than in the halls of Congress.

Though the black family emerged as a durable and vital institution after slavery, the strains of war took a tremendous toll on relations between husbands and wives, parents and children. For many households and individuals, the transition between bondage and freedom was a wrenching one, provoking disputes over property, over the custody of children, and over the reciprocal obligations of family members to one another. Some women took advantage of local Freedmen’s Bureau courts to file grievances against abusive husbands or other kin whom they felt had wronged them. Not surprisingly, the dislocations of war in the form of migrations, forced and otherwise, and the reconstitution of families prompted marital difficulties not easily resolved. Some partners refrained from formalizing marital arrangements initiated under slavery, instead preserving informal bonds—but in the process rendering more problematic a whole host of contested issues related to social relationships and property ownership.

38Nevertheless, as soon as they were free, most blacks attempted to set their own work pace and conspired to protect one another from the white man’s (and woman’s) wrath. Plantation managers charged that freedpeople, hired to work like slaves, were “loafering around” and “lummoxing about.” More than one postwar overseer, his “patience worn plum out,” railed against “grunting” blacks (those “pretending to be sick”) and others who sauntered into the fields late in the day, left early to go fishing, or stayed home altogether; “damd sorry work” was the result. Modern economic historians confirm contemporary estimates that by the 1870s, the amount of black labor in the fields had dropped to one-quarter or one-third pre-emancipation levels.

39This fact does not mean that all black women throughout the South were refusing to work, however. We have seen that many single women, especially those with children, continued to toil for whites, in some cases on the same plantation for their former master or mistress. In addition, women in specific crop economies sought to adjust their own work patterns in response to current or historic grievances. For example, in the sugar parishes of Louisiana, black wives constituted a supplemental force and went out into the fields during the busiest seasons, in contrast to their husbands, who labored for wages on a full-time basis. In Mississippi freedwomen broke from their slave past of gang labor and remained alert to wage-earning opportunities that varied with the season of the year—as hoers or as pickers of cotton, or as laundresses. Near Columbus nearly every wife took in washing, receiving nine dollars each month in return, her boiling kettle a testament to her desire to earn money and at the same time care for her children at home. In low-country South Carolina, black women continued to plant and harvest rice, but they refused to do mudwork, the cold and disagreeable wintertime tasks. In response, planters had to hire Irish immigrant day laborers from Charleston and Savannah .

40Thus withdrawal of black females from full-time labor in the fields—a major theme in both contemporary and secondary accounts of Reconstruction—constituted a “radical change in the management of [white] households as well as plantations” and proved to be a source of “absolute torment” for former masters and mistresses (in the words of a South Carolina newspaper in 1871). The female field-hand who labored day in and day out, all year long under the ever-watchful eye of an overseer came to symbolize the old order.

41Employers made little effort to hide their contempt for freedwomen who “played the lady” and refused to join male workers in the fields. To apply the term “ladylike” to a black woman was apparently the height of sarcasm; by socially prescribed definition, black women could never become “ladies,” though they might display pretensions in that direction. The term itself had predictable “racial” and class connotations. Well-to-do white ladies remained cloistered at home, fulfilling their marriage vows of motherhood and genteel domesticity. But black housewives appeared “most lazy”; in the words of disapproving whites, these women stayed “out of the fields, doing nothing,” demanding that their husbands “support them in idleness.” At the heart of the issue lay the whites’ notion of productive labor; black women who eschewed work under the direct supervision of former masters did not really “work” at all, regardless of their family household responsibilities.

42In their haste to declare “free labor” a success, even Northerners and foreign visitors to the South ridiculed “lazy” freedwomen working within the confines of their own homes. Hypocritically—almost perversely—these whites questioned the “manhood” of husbands whom they charged were cowed by domineering female relatives. South Carolina Freedmen’s Bureau agent John De Forest, for example, wrote that “myriads of women who once earned their own living now have aspirations to be like white ladies and, instead of using the hoe, pass the days in dawdling over their trivial housework, or gossiping among their neighbors.” He disdained the “hopeless” look given him by men told “they must make their wives and daughters work.” George Campbell, a Scotsman touring the South in 1878, declared, “I do not sympathize with negro ladies who make their husbands work while they enjoy the sweets of emancipation.”

43Most southern and northern whites assumed that the freedpeople were engaged in a misguided attempt to imitate middle-class white norms as they applied to women’s roles. In fact, however, the situation was a good deal more complicated. First, the reorganization of female labor resulted from choices made by both men and women. Second, it is inaccurate to speak of the total “removal” of women from the agricultural workforce. Many were no longer working full-time for a white overseer, but they continued to labor according to seasonal demands of the crop, and according to the needs and priorities established by their own families.

An Alabama planter suggested in 1868 that it was “a matter of pride with the men, to allow all exemption from labor to their wives.” He told only part of the story. Accounts provided by disgruntled whites suggest that husbands did often take full responsibility for deciding which members of the family would work, and for whom: “Gilbert will stay on his old terms, but withdraws Fanny and puts Harry and Little Abram in her place and puts his son Gilbert out to a trade,” reported Mary Jones, a Georgia plantation mistress, in January 1867. Before the war, her clergyman husband had exhorted his enslaved workers to marry and be faithful to their spouses; now the family responsibilities assumed by black husbands and fathers appeared to threaten the material well-being of white households. At the same time, there is good reason to suspect that wives willingly devoted more time to childcare and other domestic matters, rather than merely acquiescing in their husbands’ demands. A married freedwoman, the mother of eleven children, reminded a northern journalist that she had had “to nus’ my chil’n four times a day and pick two hundred pounds cotton besides” under slavery. She expressed at least relative satisfaction with her current situation: “I’ve a heap better time now’n I had when I was in bondage.”

44The humiliations of slavery remained fresh in the minds of black women who continued to suffer physical abuse at the hands of white employers, and in the minds of their menfolk who witnessed or heard about such acts. It was not surprising then that freedmen attempted to protect their womenfolk from rape and other forms of assault; as individuals, some intervened directly, while others went to local Freedmen’s Bureau agents with accounts of beatings inflicted on their wives, sisters, and daughters. Bureau records include the case of a Tennessee planter who “made several base attempts” upon the daughter of the freedman Sam Neal (his entire family had been hired by the white man for the 1865 season). When Neal protested the situation, he was deprived of his wages, threatened with death, and then beaten badly by the white man and an accomplice. As a group, men sought to minimize chances for white male-black female contact by removing their female kin from work environments supervised closely by whites.

45At first, cotton growers persisted in their belief that gangs afforded the most efficient means of labor organization because they had been used with relative success under slavery and facilitated centralization of control. Overseers had only to continue to force blacks to work steadily. However, Charles P. Ware, a Yankee cotton agent with Philbrick on the Sea Islands, noted as early as 1862: “One thing the people are universally opposed to. They all swear that they will not work in a gang, i.e., all working the whole, and all sharing alike.” Freed men and women preferred to organize themselves into kin groups, as evidenced by the “squad” system, an intermediary phase between gang labor and family sharecropping. A postwar observer defined the squad as “a strong family group, who can attach other labour, and bring odd hands to work at proper seasons”; this structure represented “a choice, if not always attainable, nucleus of a ‘squad.’” The squad usually numbered less than a dozen people (seven was average), and performed its tasks under the direction of one of its own members. In this way kinship patterns established under slavery coalesced into work relationships after the war. Still, blacks resented an arrangement under which they continued to live together in old slave quarters grouped near the landowner’s house and lacked complete control over the work they performed in the field. And black women played a pivotal role in the emergence of families and households as units of economic production after the war.

46In the late 1860s this tug of economic and psychological warfare between planters determined to grow more cotton and blacks determined to resist the old slave ways culminated in what historians have called a “compromise”—the sharecropping system. It met the minimal demands of each party—a relatively reliable source of labor for white landowners, and, for freedpeople (more specifically, for families), a measure of independence in terms of workplace decision making. Sharecroppers moved out of the old cabins and into small houses scattered about the plantation. Fathers and husbands renegotiated contracts around the end of each calendar year; families not in debt to their employers for equipment and fertilizer often seized the opportunity to move in search of a better situation. By 1870 the “fifty-fifty” share arrangement under which planters parceled out to tenants small plots of land and provided rations and supplies in return for one-half the crop predominated throughout the Cotton South .

47The cotton sharecropping system helped to reshape southern class and gender relations even as it preserved a backward agricultural economy. The linking of personal financial credit to crop liens and the rise of debt peonage enforced by criminal statutes guaranteed a large, relatively immobile labor force at the expense of economic and social justice. In increasing numbers, poor whites would come under the same financial constraints that ensnared black people. Before the war, white women of modest means had helped sustain self-sufficient households by keeping gardens, producing cloth, and engaging in other tasks similar to those of the colonial housewife. After 1865, many of these households had to rely on loans from creditors who insisted on crops of cotton as a “lien” on the debt. Poor harvests bankrupted these small farmers. With the descent of these previously independent households into landlessness and tenancy, women were drawn into the cotton fields to pursue single-mindedly the largest crop their family could produce.

48Although data from 1870 presents only a static profile of black rural households in the Cotton South, it is possible to make some generalizations (based on additional forms of evidence) about the status of freedwomen five years after the war. The vast majority (91 percent) lived in rural areas. Illiterate and very poor (even compared to their poor white neighbors), they nonetheless shared the mixed joys of work and family life with their husbands, children, and nearby kin. Fertility rates declined very slowly from 1830 to 1880; the average mother in 1870 had six or seven children. The lives of these women were severely circumscribed, as were those of other family members. Most of the children never had an opportunity to attend school—or not with any regularity—and began to work in the fields or in the home of a white employer around the age of ten or twelve. Young women found it possible to leave their parents’ home earlier than did the men they married. As a group, black women were distinguished from their white neighbors primarily by their extreme poverty and by the greater reliance of their families on the work they did outside the realm of traditional domestic responsibilities. (See Appendix B.)

49Within the limited public arena open to blacks, the husband represented the entire family, a cultural preference reinforced by demographic and economic factors. In 1870, 80 percent of black households in the Cotton Belt included a male head and his wife, a proportion identical to that in the neighboring white population. (Future commentators who posited that female-headed households revealed an unbroken line between slavery and the twentieth century were mistaken.) In addition, most of the husbands were older than their wives—in more than half the cases, four years older; in one out of five cases, at least ten years older. Thus these men exercised authority by virtue of their age as well as their gender.

Landowners, merchants, and Freedmen’s Bureau agents acknowledged the role of the black husband as the head of his family at the same time they encouraged his wife to work outside the home. He took “more or less land according to the number of his family” and placed “his X mark” on a labor agreement with a landowner. Just as slaveholders had dealt opportunistically with the slave family—encouraging or ignoring it according to their own perceived interests—so postbellum planters seemed to have had little difficulty adjusting to the fact that freedmen’s families were structured “traditionally” with the husband serving as the major source of authority. Patrick Broggan, an employer in Greenville, Alabama, agreed to supply food and other provisions for wives and children—“those who do not work on the farm”—“at the expense of their husbands and Fathers,” men who promised “to work from Monday morning until Saturday night, faithfully and lose no time.”

50Freedmen’s Bureau’s guidelines mandated that black women and men receive unequal compensation based on their gender rather than their productive abilities or efficiency. Agents also at times doled out less land to families with female (as opposed to male) household heads. Moreover, the bureau tried to hold men responsible for their wives’ unwillingness to labor according to a contractual agreement. For example, the Cuthbert, Georgia, bureau official made one black man promise “to work faithfully and keep his wife in subjection” after the woman refused to work and “damned the Bureau” saying that “all the Bureaus out [there] can’t make her work.” Left unstated in these contracts was the assumption that black women’s domestic labors—tending gardens and keeping chickens for example— provided substantial support for families and thereby lessened landlords’ need to provide much in the way of cash compensation for a year’s labor.

51A sharecropper usually purchased the bulk of the family’s supplies either in town or from a rural local merchant, and arranged to borrow or lease any stock animals that might be needed in plowing. He received direct payment in return for the labor of a son or daughter who had been “hired out.” (A single mother who operated a farm might have delegated these responsibilities to her oldest son or another male kin relation, or tried to assume responsibility for them herself.) Finally, complaints and criminal charges lodged by black men against whites often expressed the grievances of an entire household.

Thus the gendered division of labor that had existed within the black family under slavery became more sharply focused after emancipation. Wives and mothers and husbands and fathers perceived domestic duties to be a woman’s major obligation, in contrast to the slave master’s view that a woman was first and foremost a field- or houseworker and only incidentally the member of a family. Now women also worked in the fields when their labor was needed as gauged by husbands and wives. At planting and especially harvest time, they joined other family members outside. During the late summer and early fall, some would hire out to white planters in the vicinity to pick cotton for a daily wage. Seasonal fluctuations in labor patterns extended to men as well. In areas where husbands could find additional work during the year—on rice plantations or in phosphate mines or sugar mills, for example—they left their “women and children to hoe and look after the crops.” Yet in general, women’s agricultural labor partook of a more seasonal character than that of their husbands.

52The fact that black families depended heavily upon the fieldwork of women and children is reflected in the great disparity between the proportion of working wives in Cotton Belt white and black households; in 1870 more than four out of ten black married women listed jobs, almost all as field laborers. By contrast, fully 98.4 percent of white wives told the census taker they were “keeping house” and had no gainful occupation. Moreover, about one-quarter (24.3 percent) of black households, in contrast to 13.8 percent of the white, included at least one working child under sixteen years of age. Rates of black female and child labor are probably quite low, since census takers were inconsistent in specifying occupations for members of sharecropping families. In any case, statistics indicate that freedmen’s families occupied the lowest rung of the southern economic ladder; almost three-fourths of all black household heads (compared to 10 percent of their white counterparts) worked as unskilled agricultural laborers. By the mid-1870s no more than 4 to 8 percent of all freed families in the South owned their own farms.

53The rural paterfamilias tradition exemplified by the structure of black family relationships after the Civil War did not challenge the value and competence of freedwomen as field-workers. Rather, a distinct set of priorities determined how wives and mothers used their time in terms of housework, field labor, and tasks that produced supplements to the family income. Thus it is difficult to separate a freedwoman’s “work” from her family-based obligations; productive labor had no meaning outside the family context. These aspects of a woman’s life blended together in the seamless fabric of rural life.

Slavery, Civil War, Reconstruction

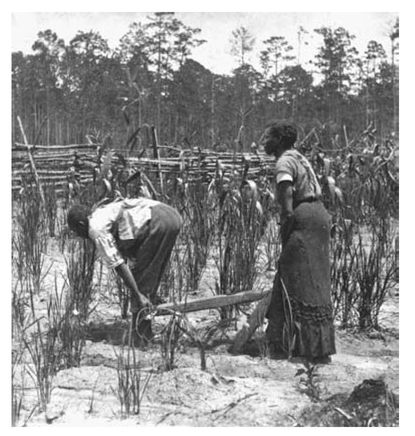

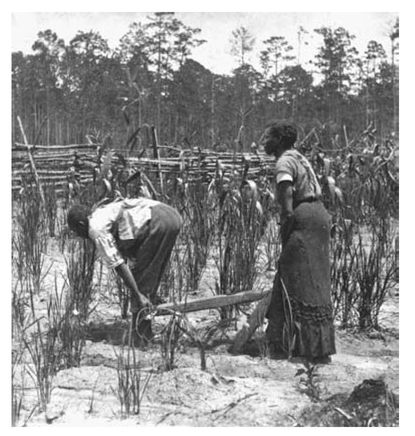

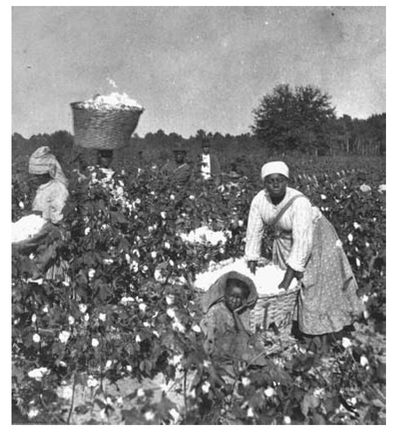

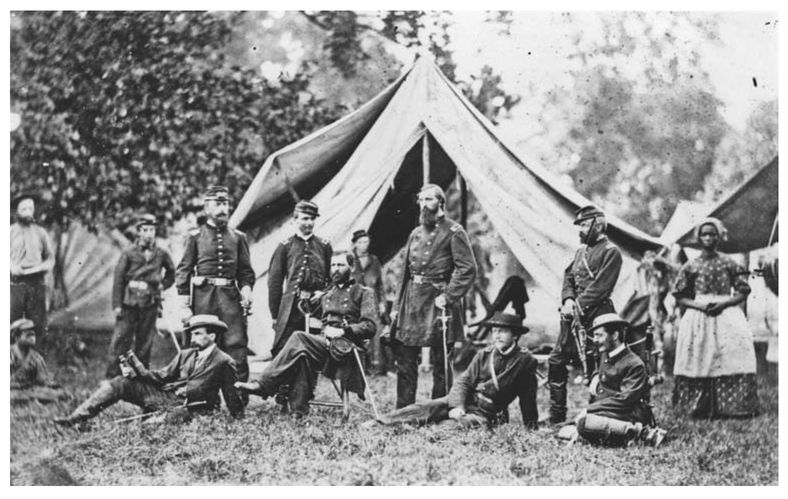

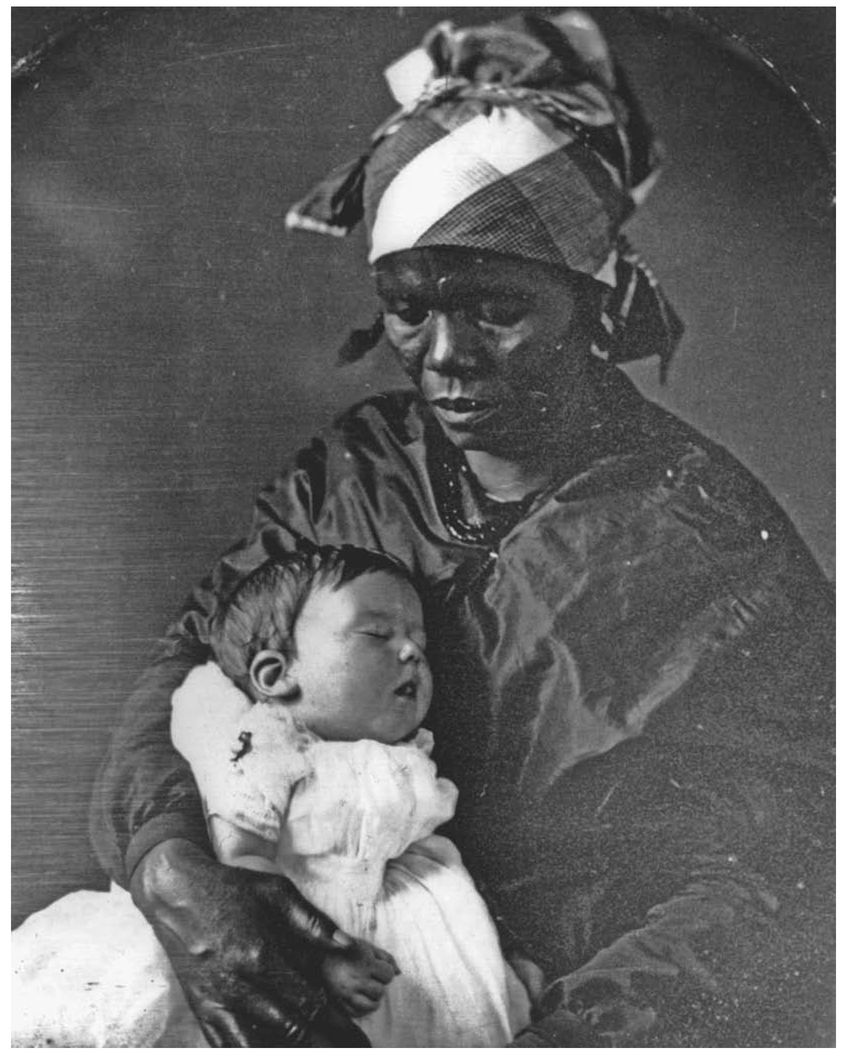

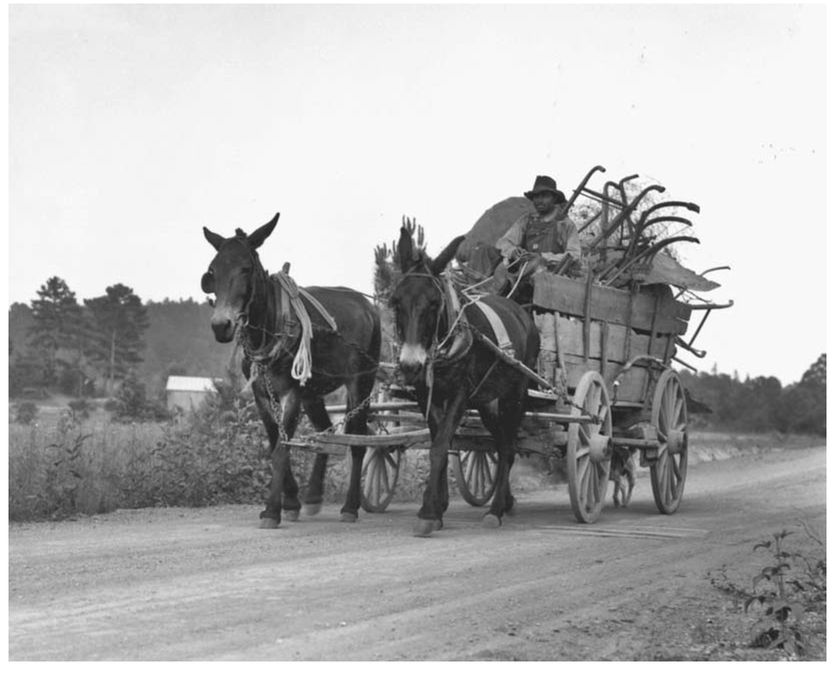

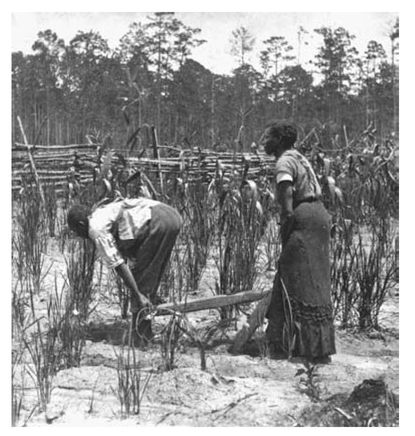

As enslaved workers and as freedwomen, black wives and mothers labored for white masters and mistresses even as they sought to provide for the everyday needs of their own families. Most enslaved women toiled in the fields for a great part of their lives (1). They formed an integral part of the labor force within the cotton economy that dominated the South’s staple-crop system of agriculture throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (2). During the Civil War, the advance of the Union army left intact the broad outlines of black women’s work. Some worked as servants (3) or laundresses for soldiers in military camps (4), where patterns of enforced deference to white men resembled those on antebellum plantations. For families who sought refuge behind Union lines, life remained hard and uncertain. With slavery abolished and the last cannon silenced, an enduring image of black womanhood remained etched in the minds of white southerners—that of a servant who responded to the daily demands of white people of all ages (5). The postbellum sharecropping economy was characterized by high rates of residential mobility within a circumscribed area, as families sought out a new landlord, and a better contractual arrangement, after the annual “reckoning” at the end of December (6).

1. Enslaved man and woman plowing rice in the soft soil of the Georgia low country. Photo by O. Pierre Havens. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

2. Enslaved workers of all ages picking cotton. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

3. Union General Fitz John Porter and his staff of officers, with servant. Headquarters of the Fifth Army Corps, Army of the Potomac, Harrison’s Landing, Virginia (1862). Photo by Mathew Brady. National Archives.

4. “Contraband of war” at Union army camp, Yorktown, Virginia (1862). Library of Congress.

5. Enslaved nurse with white baby (c. 1845). Massachusetts Historical Society.

6. A sharecropper on the move. National Archives.

Since husbands and wives had different sets of duties, they needed each other to form a complete economic unit. As one Georgia black man explained to George Campbell in the late 1870s, “The able-bodied men cultivate, the women raise chickens and take in washing; and one way and another they manage to get along.” When both partners were engaged in the same kind of work, it was usually the wife who had stepped over into her husband’s “sphere.” For instance, Fanny Hodges and her husband wed the year after they were freed. She remembers, “We had to work mighty hard. Sometimes I plowed in de fiel’ all day; sometimes I washed an’ den I cooked.” Cotton growing was labor-intensive in a way that gardening and housework were not, and a family’s ability to obtain financial credit from one year to the next depended upon the size of past harvests and the promise of future ones. Consequently the crop sometimes took precedence over other chores in terms of the allocation of a woman’s energies.

54Age was also a crucial determinant of the division of labor in sharecropping families. Participation in household affairs could be exhilarating for a child aware of her own strength and value as a field-worker during these years of turmoil. Betty Powers was only eight years old in 1865, but she long remembered days of feverish activity for the whole family after her father bought a small piece of land in Texas: “De land ain’t clear, so we ’uns all pitches in and clears it and builds de cabin. Was we ’uns proud? There ’twas, our place to do as we pleases, after bein’ slaves. Dat sho’ am de good feelin’. We works like beavers puttin’ de crop in.” Sylvia Watkins recalled that her father gathered all his children together after the war. She was twenty years old at the time and appreciated the special significance of a family able to work together: “We wuked in de fiel’ wid mah daddy, en I know how ter do eberting dere ez to do in a fiel’ ’cept plow.”

55At least some children resented the restrictions imposed by their father who “raised crops en made us wuk in de fiel.” The interests of the family superseded individual desires. Fathers had the last word in deciding which children went to the fields, when, and for how long. As a result some black women looked back on their years spent at home as a time of personal opportunities missed or delayed. The Federal Writers Project Slave Narrative Collection contains examples of fathers who prevented daughters from putting their own wishes before the family’s welfare during the postbellum period. Ann Matthews told a federal interviewer: “I didn’t go ter schul, mah daddy wouldin’ let me. Said he needed me in de fiel wors den I needed schul.” Here were two competing “needs,” and the family came first.

56The status of black women after the war cannot be separated from their roles as wives and mothers within a wider network of kinship. Like poor people in general, blacks in the rural South relied upon kin and community in ways that defied the liberal ethos of unfettered individualism. Local communities shaped people’s everyday lives. Indeed, more than one-third of all black households in the Cotton Belt lived in the immediate vicinity of people with the identical (paternal) surname, providing a rather crude—and conservative—index of local kinship clusters. As the persons responsible for child nurture and social welfare, freedwomen cared not only for members of their nuclear families, but also for dependent relatives and others in need. This post-emancipation cooperative impulse was a legacy of a collective ethos developed under slavery, but also a characteristic of all kinds of impoverished rural communities.

57The former slaves’ attempts to provide for one another’s needs appear to have been a logical and humane response to widespread hardship during the 1860s and 1870s. Nevertheless, whites spared from physical suffering, including southern elites and representatives of the northern professional class, often expressed misgivings about this form of benevolence. They believed that any able-bodied black person deserved a “living” only to the extent that he or she contributed to the southern commercial economy. Blacks should reap according to the cottonseed they sowed, the rice they planted, the sugar cane they harvested. Soon after she returned to her family’s Sea Island estate in 1866, Frances Butler thought there was nothing else “to become of the negroes who cannot work except to die.” In this way she masked her grief over the death of slavery with professed concern for ill, young, and elderly freedpeople. But within a few months she declared with evident irritation, “It is a well-known fact that you can’t starve a negro.” Noting that about a dozen people on Butler’s Island did not work in the cotton fields and so received no clothes or food supplies, the white woman admitted that she saw “no difference whatever in their condition and those who get twelve dollars a month and full rations.” Somehow the field-workers and non-workers alike managed to take care of themselves and one another by growing vegetables, catching fish, and trapping game. Consequently they relied less on wages paid by their employer. The threat of starvation proved to be a poor taskmaster in compelling these freedpeople to toil for Frances Butler.