SIX

HARDER TIMES

The Great Depression

IN 1930,

Apex News, the publication of Apex Beauty Products Company, told its readers, “No matter how hard times are, people must do four things—eat, be housed, clothed, and look well. The harder times are, the more people stress looks and appearance.” The manufacture, selling, and use of cosmetics and other beauty products remained, according to the

News, a “Depression-proof business,” one that offered unparalleled opportunities for black women seeking to earn a decent living during the deepening economic crisis. The founder of Apex, Sarah Spencer Washington, personified the lucrative nature of the beauty industry, for out of her headquarters in Atlantic City, New Jersey, she built an empire of highly profitable, interconnected businesses; at its height, in addition to publishing

Apex News, her company sold 75 different kinds of beauty products, employed 35,000 sales agents around the United States, and operated eleven beauty schools that produced 4,000 graduates annually, many of whom started their own beauty shops. In building one of the largest black businesses in the country, Washington was confident, “As long as there are women in the world, there will be beauty establishments.”

1With her expansive entrepreneurial and philanthropic impulses, Washington resembled Madame C. J. Walker and other promoters of beauty products, long a mainstay of the black community. These businesswomen were dependent on no white man or woman. During the Great Depression, such enterprises, including product sales, beauty shops, and beauty schools, achieved heightened social and economic significance. Though laundresses and domestic servants earned little, they enjoyed patronizing neighborhood beauty parlors, where they could spend time and money on their appearance, socialize with friends, and support multiple black-owned businesses, including the hairdresser herself and the products she used. At the same time, black beauty-shop owners registered the effects of the Great Depression, for even the most successful—for example, those serving middle-class customers in Harlem—earned only $16 a week, not enough to pay their workers the minimum wage established by new federal legislation. Most black beauticians worked either out of their own homes or out of a small booth in a store, and, in contrast to the reassurances of

Apex News and other publications, barely, or rarely, made ends meet. Regardless of their circumstances, these working women labored for long hours for uncertain pay, and competition for clients was cutthroat. Operators lowered their prices—for example, halving the $1.50 to $2.00 they used to charge for shampooing and pressing—or bartered their services “for food, clothing, or anything else of use to them.” Employees of small shops who managed to hold on to their jobs suffered a dramatic drop in wages, while their hours remained the same.

2Moreover, the nature of the work itself was not always an improvement over domestic service: One Harlem worker remarked, “We learned beauty culture to get away from sweating and scrubbing other people’s floors, and ran into something just as bad—scrubbing people’s scalps, straightening, and curling their hair with a hot iron all day, and smelling frying hair.” And more than one beautician grew weary of hearing the incessant complaints of customers determined to take advantage of a captive audience to rail against their employers; “You’d think on their day off they’d forget their madams,” lamented one beautician, who heard more than she wanted to know from each customer about “what my madam said.” Nevertheless, by the 1920s and the 1930s, the African American beauty business had emerged as one of the few industries controlled exclusively from top to bottom by black women, a fact of considerable political import, especially after World War II.

3“Our people have always known how to season a pot,” goes an African American saying that has special relevance for the period between 1929 and 1941. Depression-like conditions were not new for the vast majority of black Americans, and over the generations they had managed to get by with little in the way of material resources. Nevertheless, 1930s unemployment data reveal that they lost what little they already had more swiftly and surely than did whites. In 1932, the black unemployment rate had reached an estimated, unprecedented 50 percent in some parts of the country. Throughout this decade, black women’s responsibilities increased in proportion to the economic losses suffered by their households; at home and on the job, wives and mothers were called upon to work even harder than they had in better times. At the same time, many women of modest means, in concert with middle-class allies, aggressively pursued their collective self-interest in the cotton fields, in urban neighborhoods, and at the highest echelons of the federal government. In the words of Mary McLeod Bethune, an influential member of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Black Cabinet” and an official of the National Youth Administration, “We have been eating the feet and head of the chicken long enough. The time has come when we want some white meat.” For the first time since Reconstruction, many African Americans held out hope that the combined efforts of the president and Congress would promote meaningful social change.

4At the very bottom of a hierarchical labor force, black men and women lost their tenuous hold on employment in the agricultural, service, and industrial sectors; economic contraction eliminated many positions, and then spurred an unequal competition with whites for the ones that remained. Concentrated in the marginal occupations of sharecropping, private household service, and unskilled factory work, many black women’s jobs had, by 1940, “gone to machines, gone to white people or gone out of style,” in the words of activist-educator Nannie Burroughs. Although the financial needs of black families intensified during the depression, black women’s labor-force participation dropped from 42 percent in 1930 to 37.8 percent ten years later, reflecting their diminished work opportunities. Wherever they did work—on farms, in white households, in the factory, and in their own homes—mothers and daughters found themselves subjected to speed-ups, performing more labor for the same or lesser rewards.

5The complex set of chain reactions that had such disastrous consequences for many Americans, and for black Americans in particular, originated with the stock market crash in October 1929 (though rural folk of both races and northern black people began to feel the effects of economic recession several years earlier). Still, patterns of black women’s work derived not only from mechanistic economic forces during these years; for example, at the national level, the federal government served in some cases as an employer of black women, regulator of their industrial working conditions and wages, and provider of social services and relief. Local white administrators, especially those in southern states, used the federal resources at their disposal to reinforce the caste system, called by some “Jim Crow.” “The job is JIM CROWED, the commodities are JIM CROWED, the very air you breathe under the Adams County Mississippi [Emergency Relief Administration] is contaminated with the parasite of JIM CROWISM,” wrote one exasperated black man to the head of the Labor Department’s Division of Negro Labor in 1935. Throughout this period, President Roosevelt remained hostage to the southern white Democrats who headed key congressional committees. Refusing to embrace antilynching legislation or black civil rights more generally, the president declared in 1933, “First things come first, and I can’t alienate certain votes I need for measures that are more important at the moment by pushing any measures that would entail a fight.” Nevertheless, the real benefits that some black families derived from federal programs, combined with highly visible gestures in the direction of egalitarianism made by Eleanor Roosevelt and a few New Deal officials, were enough to inspire a massive defection on the part of black voters from the Republican to the Democratic Party. In 1936, FDR received more than three-quarters of the black vote, a testament to the fact that northern black voters received their approximate fair share of jobs and relief, in contrast to southern blacks, the overwhelming majority of whom remained disenfranchised and thus powerless to counter the prejudicial decisions of local administrators.

6Labor unions revitalized and inspired by federal legislation in the mid-1930s, and radical political parties and community organizations galvanized by widespread social unrest, also shaped patterns of black women’s work. Black women participated in broader labor and political struggles when they organized coworkers into a union affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), helped to build an organization of displaced sharecroppers, joined the Communist Party, or lobbied on behalf of the newly formed National Council of Negro Women (founded by Mary McLeod Bethune). According to writer Richard Wright, their initial, Depression-era encounters with a more expansive world, one that included in some cases white coworkers, represented for blacks “the death of our old folk lives, an acceptance of a death that enabled us to cross class and racial lines, a death that made us free.”

7Yet Wright’s epitaph for black folk consciousness was premature. Black nationalist and neighborhood welfare coalitions continued in the generations-old African American tradition of cooperation and group advancement. In addition, networks of kin and neighbors assumed critical significance among black women who had fewer resources with which to care for greater numbers of unemployed household members. As Annie Mae Hunt, a domestic, told her children in the 1930s, “You don’t need no

certain somebody. You need

somebody. Somebody. That’s all you need . . . but you got to have somebody that cares.” Together, black sisters, mothers, grandmothers, and daughters relied on one another to get them through these harder times; as individuals many of them demonstrated strength and determination in ways they themselves did not always fully comprehend. The sole support of her three children, an East St. Louis black woman worked for meager wages as a meat trimmer during the day and did all her own housework and provided for a boarder in the evenings; in response to the queries of a government investigator in 1937, she admitted, “I don’t hardly see myself how I make out.”

8Thus black women’s work in the 1930s took place within a matrix of federal action, class-based and black political activism, neighborly cooperation, and personal initiative. However, structural factors related to the American economic and political system inhibited meaningful change in the status of black women, relegated as they were to the fringes of a developing, though crippled, industrial economy. Most New Deal labor legislation targeted the employees of large industrial establishments; these employees were covered by new laws related to unemployment compensation, minimum wages and hours, and Social Security. Left out of these provisions were domestic servants, part-time workers, and agricultural laborers—that is, the vast majority of black men and women. Moreover, legislative measures that did ameliorate the condition of unemployed black working women at times could adversely affect their status as family members; for example, the welfare state provided minimal cash payments for single mothers with dependents, but it injected a new source of tension into marital relationships. In the end, trends related to national and regional economic development, combined with bureaucratic shortsightedness and prejudice, preserved the historic vulnerabilities endured by black women workers. Of the persistence of antiblack discrimination in the 1930s, one trenchant observer noted, “The devil is busy.” But so too were hundreds of thousands of black women wage earners, community leaders, and housewives who faced “an old situation [with] a new name, ‘depression.’”

9

DIMINISHING OPPORTUNITIES IN THE PAID LABOR FORCE

High unemployment rates among their husbands and sons forced many white wives to enter the labor market for the first time in the 1930s. At the same time, black men were experiencing even higher rates of joblessness; their distress caused their wives to cling more desperately to the positions they already had, despite declining wages and deteriorating working conditions. During the Great Depression, most black women maintained only a precarious hold on gainful employment; their positions as family breadwinners depended upon, in the words of one social worker, “the breath of chance, to say nothing of the winds of economic change.” Unemployment statistics for the 1930s can be misleading because they do not reveal the impact of a shifting occupational structure on divergent job options for black and white women. Just as significantly, the relatively high rate of black females’ participation in the labor force obscures the highly temporary and degrading nature of their work experiences. Specifically, most of these women could find only seasonal or part-time employment; persistent forms of discrimination deprived them of a living wage no matter how hard they labored; and they endured a degree and type of workplace exploitation for which the mere fact of having a job could not compensate. During the decade, nine out of ten black women workers toiled as agricultural laborers or domestic servants. Various pieces of federal legislation designed to protect and raise the purchasing power of workers (most notably the National Industrial Recovery Act [1933], the Social Security Act [1935], and the Fair Labor Standards Act [1938]) exempted these two groups of workers from their provisions. In essence, then, no more than 10 percent of gainfully employed black women derived any direct benefit from the new federal policies designed primarily to cushion industrial wage earners against the regular upturns and downswings characteristic of a national market economy. Indeed, these policies were crafted not only by southern congressmen, but also by liberal New Dealers who believed that semiskilled assembly-line workers constituted the backbone of the American economy.

10Despite the rapid decline in a wide variety of indicators related to production and economic growth in the early 1930s, and despite the sluggishness of the pre-1941 recovery period, the numbers and kinds of job opportunities for white women expanded, as did their need to help supplement household income. The clerical sector grew (as it had in the 1920s) and would continue to do so in the 1940s, and in the process attracted more and more women into the workforce and employed a larger proportion of all white women workers. (The percentage of white women who were gainful workers steadily increased throughout the period 1920 to 1940 from 21.3 to 24.1 percent of all adult females.) At least during the early part of the depression decade, unemployment rates in the male-dominated industrial sector were generally higher than those in the female-dominated areas of sales, communications, and secretarial work. But the fact of gender segmentation in the labor force benefited white women, for black women had no access to white women’s work even though (or perhaps because) it was deemed integral to both industrial capitalism and the burgeoning federal bureaucracy. In 1940 one-third of all white, but only 1.3 percent of all black, working women had clerical jobs. On the other hand, 60 percent of all black female workers were domestic servants; the figure for white women was only 10 percent.

11During the 1930s, a public debate over the propriety of working wives raged in city council chambers, state legislatures, union halls, and the pages of popular magazines, indicating that persons on both sides of the question assumed it was a new and startling development. As historian Alice Kessler-Harris has pointed out, “Issues involving male and female roles, allowed to pass unnoticed for generations because they affected mostly poor, immigrant, and single women, assumed central importance when they touched on the respectable middle class.” Few congressmen or labor leaders evinced much concern over the baneful effects of economic dependence on the male ego when the ego in question was that of a black husband. Moreover, white female school teachers, social workers, and factory workers deprived white men of job opportunities in a way that black domestic servants did not. Working wives became a public issue to the extent that they encroached upon the prerogatives of white men at home and on the job.

12

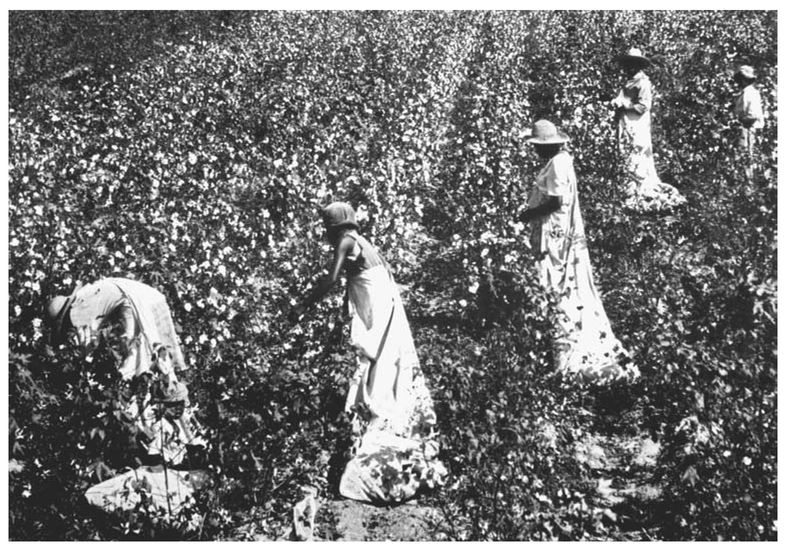

Women Who Daily “Hit the Sun”13: Black Farmworkers in the 1930s

Government programs that sought to limit crop production and raise the price of food had two major effects on black women: First, they hastened the displacement of sharecropping families that were now too costly to furnish (i.e., supply with credit) and that were no longer necessary to the staple-crop economy; and second, they enabled large planters to invest their cash subsidies in farm machinery, in the process reducing tenants and sharecroppers to the status of hired hands. Thus the Depression represented a major turning point in the history of southern farming, as the plantation labor system was transformed from sharecropping to wage labor, and the number of persons who made their living from the land declined rapidly. Of all black working women in 1940, 16 percent were employed in agriculture, down from 27 percent ten years earlier.

14A cornerstone of the early New Deal, the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA, passed in 1933), provided compensation for planters who grew less, and tenants were supposed to benefit from a portion of this allotment. In fact, plantation owners often failed to pass on to their tenants any of the money at all, arguing that the funds should be used to retire the (often concocted) debts of individual families. Others dispensed with the problem altogether by evicting tenants en masse or by “splitting” households to distinguish between productive and incapacitated or youthful members. National welfare policies indirectly encouraged this practice. For example, the Federal Emergency Relief Act of 1933 (FERA) made provisions for the distribution of relief funds by local private and governmental agencies to rural farm families. Thus an owner might agree to contract with individual able-bodied men and women (rather than a family unit) under the assumption that children needed very little anyway and that FERA would take care of the elderly. A confidential FERA report of July 1934 noted that “theoretically, [the average white planter] says that the landowner should maintain his tenants, if able, but actually, since he has had a taste of government relief, he is loathe to give it up.”

15Together, these policies increased the fieldwork and family obligations of rural black women. Household members “dropped” by a landlord might not be “picked up” by a relief program, thus forcing wives and mothers to stretch their skimpy resources and provide for children or elderly kin and neighbors deprived of any direct source of income. As workers, these women found that the value of their labor had decreased, not only in terms of cash earned from the sale of cotton, but also in terms of the basic supplies—food, fertilizer, and equipment—furnished to each household by the landlord. At times new kinds of deprivation had wide-ranging and not fully anticipated consequences. A female sharecropper who testified before a national conference on economic recovery in the mid-1930s noted that her family’s inability to purchase fertilizer meant that the children had no clothes to wear, since she was used to making their “aprons and dresses” from the rough burlap bags fertilizer came in. When it came to clothing the children, fertilizer sacks were better than nothing.

16Furthermore, black women’s status declined relative to that of first, their poorest white neighbors, who were more likely to receive government assistance, and more of it; and second, industrial wage earners. Agricultural labor in the 1930s had an intensive, primitive quality, prompting one sociologist to suggest that “it seems to take a good deal of social pressure to get people to do this work.” Mechanical advances had cut down on the amount of labor required for plowing furrows and hoeing rows of crops, but workers still did most of the harvesting by hand. Stooped over, moving slowly down long rows and picking cotton bolls or worming tobacco plants, or on their knees following a plow and “grabbling” in the earth for potatoes, those women who labored in the fields resembled their early-nineteenth-century foremothers in all but dress; now thinner, short-sleeved cotton dresses had replaced the hot, heavy osnaburgs of the antebellum period.

17In an effort to work their way out of chronic indebtedness, some black farm women took short-term, nearby jobs as wage laborers for the rate of forty to fifty cents a day. A 1937 Women’s Bureau report noted that the female cotton-pickers of Concordia Parish, Louisiana, earned a total of $41.67 annually; most found, or accepted, gainful employment for less than ninety days each year. Those who continued to labor as sharecroppers of course received only a ramshackle room and meager board, but virtually nothing in cash. For some women, the stability and closeness of kin ties compensated for the lack of money. A thirty-eight-year-old mother who had left her husband and returned to her childhood home told an interviewer that though “she usually received nothing at the end of the year [it] was of no importance to her as long as she lived with her mother and brother and sister.” Still, the irony of the situation was unavoidable. In her 1931 study of black female cotton laborers in Texas, Ruth Alice Allen calculated that they produced about one-eighth of the state’s crop yet earned “no return but a share in the family living.”

18Migratory labor represented an extreme form of farm workers’ displacement. During the Great Depression, public attention focused on the white “Okies” who fled dust bowl conditions in the South and Southwest to seek an ever-elusive harvest of plenty on the West Coast. Blacks did not participate in this general population movement to any great extent because of the lack of mass (that is, rail) transportation and because they could not depend upon securing basic services such as food and gas en route in private automobiles. Yet in response to “reduced earnings in their usual work,” family groups, for the first time on a large-scale basis, began to travel up and down the eastern seaboard, living in labor camps while working in Florida orange groves, Delaware canneries, and the fields of New Jersey truck farms. Recorded by the Women’s Bureau in 1941, the story of the “A” family, a young Maryland couple, was typical. In 1939 Mrs. A had worked as a domestic and her husband as an oyster shucker, but “neither of these occupations afforded very full or steady employment.” The next year between March and September they picked berries and canned tomatoes in Delaware, “grabbled” potatoes in Virginia, and harvested cucumbers in Maryland. Nine months of sporadic work had earned them only $330, one-third of which was Mrs. A’s contribution. In their exploitative working and living conditions, seasonal employment, poor pay, and strong commitment to family ties, this husband and wife had much in common with all black agricultural laborers.

19Migrant laborers and sharecroppers did have advocates within the Roosevelt administration. Officials in the Resettlement Administration (1935), and in the Farm Security Administration (FSA) that replaced it in 1937, initiated a number of programs intended to offset the disastrous effects of the AAA on the southern and midwestern rural poor. These officials created and administered cooperative farming ventures, government-sponsored migratory labor camps, low-cost housing projects, and low-interest loans for tenants with an exceptional degree of egalitarianism. Many of these projects benefited black women as heads of households, farm wives, and day laborers. In addition, the documentary photography project sponsored by the FSA preserved striking images of working women for all posterity; these portraits in black and white, which conveyed both the dignity and the desperation of so many housewives, were stark reminders of the physical arduousness of a farm mother’s daily labor. Yet the radical nature of FSA programs provoked the wrath of large landholding interests and budget-cutting congressmen, and so affected relatively small numbers of people. Always understaffed and underfunded, the administration made loans to only a few thousand farmers, compared to the estimated million people driven from the land during the decade.

20However, neither black nor white tenant farmers sat and waited passively for government aid. As early as 1931, the Communist Party helped to establish a Share Croppers Union (SCU) in Alabama, and party workers, like the young black woman Estelle Milner, were distributing copies of the party journal

Southern Worker in the state’s rural areas. This group never had many members, and it was superseded in 1934 by the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU), founded in Tyronza, Arkansas, with the help of the Socialist Party, in response to evictions precipitated by AAA programs. A year later the STFU claimed ten thousand members, at least half of them black, ample proof of its conviction that labor organizing among blacks as well as whites should begin with grassroots activity and not just rhetorical pronouncements from the upper echelons of the party. In its call for cooperative agricultural communities, the union posed an implicit threat to the southern plantation system. The efforts of southern senior politicians, landowners, and law-enforcement and judicial officials to crush the movement by any means possible—harassment, dynamite, and murder were among the tested strategies—provided a measure of that threat. AAA policymakers worked strenuously against the union and even purged its own ranks of its supporters. The STFU therefore lost much of its power after 1936. Years later Ned Cobb, who was active in the Alabama SCU and later imprisoned for his role in it, said that “it was a weak time amongst the colored people. They couldn’t demand nothin’; they was subject to lose what they had if they demanded any more.”

21Nevertheless, during its brief life, the STFU emerged as a vital political organization that relied on the commitment of women and men, blacks and whites. As one member later recalled, “Women were very active . . . and made a lot of decisions.” Naomi Williams, a member of the Gould, Arkansas, local, cultivated a cotton patch of her own, daily picked up to three hundred pounds of a white landowner’s crop, kept a vegetable garden, and taught school for her neighbors’ children. “I done worked myself to death,” she said as she explained to an interviewer why she became active in the union, and she spoke bitterly of the tremendous amount of labor necessary to keep her family together in a society that limited schooling for black children to seven months a year, “and the white kids . . . going to school all kind of every way.” Other black women, like Carrie Dilworth and Henrietta McGee, earned long-lived reputations for their organizing and speaking abilities in the face of violent intimidation. Arkansas wives and mothers participated in the 1935 general strike of cotton-pickers and, together with their families, Missouri “Bootheel” women made national headlines when they camped out along a roadside in the winter of 1939. This mass demonstration did much to bring to public attention the plight of a “poor people in a rich land.”

22In concert with their white neighbors and middle-class allies, black agrarian radicals in the 1930s left a legacy of resistance to their grandchildren but had little impact upon the emerging neoplantation system that relied on the labor of hired hands. All over the South, black families continued to yearn for economic independence, which they defined as a title to their own land, free of debt and government encumbrance. In rural eastern North Carolina, Gracie Turner stretched the $12 her husband earned each month digging up tree stumps on a public works project; she made it “do all it will” for nine people but resented the fact that public works took farmers away from the land: “Able-bodied landers has got no business a-havin’ to look to de gover’ment for a livin’,” she said. “Dey ought to live of’n de land. If ’twas fixed right dey’d make all de livin’ dey need from de ground.” A proud woman with her two feet rooted firmly in the southern soil, Gracie Turner believed that relief should come in the form of structural change, not piecemeal make-work; if the sharecropping system were only “fixed right,” people could make a decent living on their own. During the 1930s, that possibility receded further and further out of sight.

23

Kitchen Speed-Ups: Domestic Service

Contemporary literary and photographic images of a stricken nation showed dejected white men waiting in line for food, jobs, and relief. Yet observers sensitive to the racial-ideological dimensions of the crisis provided an alternative symbol—that of a middle-aged black woman in a thin, shabby coat and men’s shoes, standing on a street corner in the dead of winter and offering her housecleaning services for ten cents an hour. If the migrant labor camp symbolized the black agricultural worker’s descent into economic marginality, then the “slave markets” in northern cities revealed a similar fate for domestic servants. And in fact, the pressures on black women to earn a living increased in proportion to the rise in their menfolk’s unemployment rates. Long accustomed to the role of breadwinner, black women of all ages now assumed even greater responsibility for the welfare of their families.

24“The ‘mart’ is but a miniature mirror of our economic battle front,” wrote two investigative reporters in a 1935 issue of the NAACP’s monthly journal,

The Crisis. A creature of the Depression, the slave market consisted of groups of black women, aged seventeen to seventy, who waited on sidewalks for white women to drive up and offer them a day’s work. The Bronx market, composed of several small ones—it was estimated that New York City had two hundred altogether—received the most attention from writers during the decade, though the general phenomenon recurred throughout other major cities. Before 1929, many New York domestics had worked for wealthy white families on Long Island. Their new employers, some of them working-class women themselves, paid as little as $5.00 weekly for full-time laborers to wash windows and clothes, iron (as many as twenty-one shirts a shift), and wax floors. These workers earned radically depressed wages: lunch and thirty-five cents for six hours of work, or $1.87 for an eight-hour day. They had to guard against various ruses that would deprive them of even this pittance—for example, a clock turned back an hour, the promised carfare that never materialized at the end of the day. As individuals they felt trapped, literally and figuratively pushed to the limits of their endurance. A thirty-year-old woman told federal interviewer Vivian Morris that she hated the people she worked for: “Dey’s mean, ’ceitful, an’ ’ain’ hones’; but what ah’m gonna do? Ah got to live—got to hab a place to steh,” and so she would talk her way into a job by boasting of her muscle power. Some days groups of women would spontaneously organize themselves and “run off the corner” those job seekers “who persisted in working for less than thirty cents an hour.”

25Unlike their country cousins, urban domestics contended directly with white competitors pushed out of their factory and waitressing jobs. The agricultural labor system served as a giant sieve; for the most part, displaced farm families went to the city rather than vying for the remaining tenant positions. The urban economy had no comparable avenues of escape; it was a giant pressure cooker, forcing the unemployed to look for positions in occupations less prestigious than the ones they held formerly or, in the event of ultimate failure, to seek some form of charity or public assistance. The hardships faced by black men—now displaced by white men seeking jobs as waiters, bellhops, and street cleaners—were mirrored in the experiences of their wives, daughters, and sisters who had long worked as domestic servants. A 1937 Women’s Bureau survey of destitute women in Chicago revealed that, although only 37 percent of native-born white women listed their “usual occupation” as domestic service, a much greater number had tried to take advantage of employers’ preferences for white servants before they gave up the quest for jobs altogether and applied for relief. Meanwhile, the 81 percent of black women who had worked in service had nowhere else to go. Under these circumstances, the mere act of hiring a black woman seemed to some to represent a humanitarian gesture. In 1934 an observer of the social-welfare scene noted approvingly, with unintentional irony, that “From Mistress Martha Washington to Mistress Eleanor Roosevelt is not such a long time as time goes. There may be some significance in the fact that the household of the first First Lady was manned by Negro servants and the present First Lady has followed her example.”

26The history of domestic service in the 1930s provides a fascinating case study of the lengths to which whites would go in exploiting a captive labor force. Those who employed live-in servants in some cases cut their wages, charged extra for room and board, or lengthened on-duty hours. However, it was in the area of day work that housewives elevated labor-expanding and money-saving methods to a fine art. General speed-ups were common in private homes throughout the North and South. Among the best bargains were children and teenagers; in Indianola, Mississippi, a sixteen-year-old black girl worked from 6:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. daily for $1.50 a week. In the same town a maid completed her regular chores, plus those of the recently fired cook, for less pay than she had received previously. (A survey of Mississippi’s domestics revealed that the average weekly pay was less than $2.00.) Some women received only carfare, clothing, or lunch for a day’s work. Northern white women also lowered wages drastically. In 1932 Philadelphia domestics earned from $5.00 to $12.00 for a forty-eight- to sixty-seven-hour work week. Three years later they took home the same amount of money for ninety hours’ worth of scrubbing, washing, and cooking, an hourly wage of fifteen cents.

27The deteriorating working conditions of domestic servants reflected the conscious choices of individual whites who took advantage of the abundant labor supply. Social workers recorded conversations with potential employers seeking “bright, lively” domestics (with the very best references) to do all the cooking, cleaning, laundry, and childcare for very little pay, because, in the words of one Pittsburgh woman, “There are so many people out of work that I am sure I can find a girl for $6.00 a week.” Indeed, at times it seemed as if there existed a perversely negative relationship between expectations and compensation. An eighty-three-year-old South Carolina black woman, Jessie Sparrow, resisted working on Sundays because, she told an interviewer in 1937, “When dey pays you dat little bit of money, dey wants every bit your time.” A southern white man demonstrated his own brand of logic when he “admitted as a matter of course that his cook was underpaid, but explained that this was necessary, since, if he gave her more money, she might soon have so much that she would no longer be willing to work for him.” Well-educated black women contended with the machinations of employment agencies that signaled to potential employers that the applicant was white (“L-H-P” stood for “Long Haired Protestant”). In Seattle, Arline Yarbrough entered the job market armed with a high-school degree and training as a typist; yet she found her options so limited—“as soon as they’d [employers] seen we were black”—she ended up piecing together a livelihood, catch-as-catch-can: “little house jobs and baby sitting jobs, which would usually be for a day or two, a week at the most . . . it was a pretty cruel situation.”

28The field of domestic service was virtually unaffected by national and state welfare policies. In the 1930s Women’s Bureau officials sought to compensate for this inaction with a flurry of correspondence, radio and luncheon-meeting speeches, and voluntary guidelines related to the “servant problem.” In her talks on the subject, bureau head Mary Anderson appealed to employers’ sense of fairness when she suggested that they draw up job descriptions, guard against accidents in the workplace, and establish reasonable hours and wages. However, the few housewives privy to Anderson’s exhortations were not inclined to heed them, especially when confronted by a seemingly compliant “slave” on the street corner. Consequently, black domestic workers in several cities, often under the sponsorship of a local Young Women’s Christian Association, Urban League branch, or labor union, made heroic but unsuccessful attempts to form employees’ organizations that would set uniform standards for service; but domestics in general constituted a shifting, amorphous group immune to large-scale organizational efforts. For example, founded in 1934 and affiliated with Building Service Union Local 149 (AFL), the New York Domestic Workers Union had only 1,000 (out of a potential of 100,000) members four years later. It advocated two five-hour shifts six days a week and insisted, “last but not least, no window washing.” Baltimore’s Domestic Workers Union (in the CIO fold) also welcomed all women and remained a relatively insignificant force in the regulation of wages and working conditions. Without adequate financial resources, leaders like New York’s Dora Jones labored to organize women who “still believe in widespread propaganda that all unions are rackets.” As a result, efforts by domestics to control wage rates informally through peer pressure or failure to report for work as promised represented spontaneous job actions more widespread and ultimately effective than official “union” activity.

29During the Depression, a long life of work was the corollary of a long day of work. Black women between the ages of twenty-five and sixty-five worked at consistently high rates; they simply could not rely on children or grandchildren to support them in their old age. The Federal Writers Project interviews with former slaves recorded in the late 1930s contain hundreds of examples of women in their seventies and eighties still cooking, cleaning, or hoeing for wages on a sporadic basis in order to keep themselves and their dependents alive. An interviewer described the seventy-seven-year-old widow Mandy Leslie of Fairhope, Alabama, as “a pillar of strength and comfort to several white households” because she did their washing and ironing every week. Living alone, her children gone, this elderly woman boiled clothes in an iron pot heated by a fire, and then rubbed them on a washboard and hung them on lines so they could be ironed the following day. Such was the price exacted from black women for the “strength and comfort” they provided whites.

30

“On The Fly” in Factories

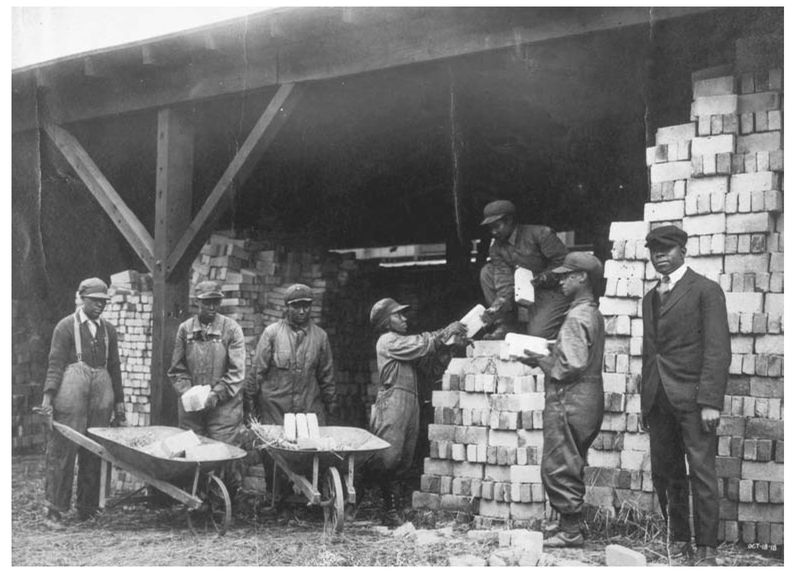

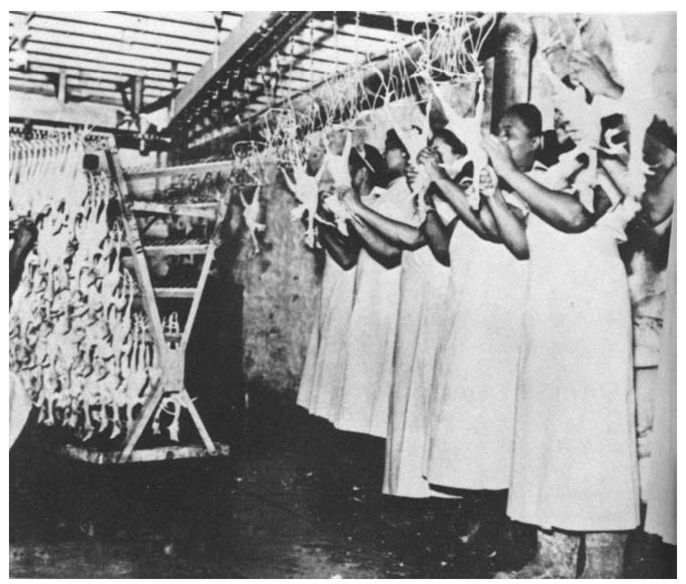

Black women’s preference for factory jobs over domestic service became almost a moot issue during the Great Depression. In 1920, 7 percent of all black female gainful workers were classified as “manufacturing and mechanical employees”; in 1930, 5.5 percent; and in 1940, 6 percent. The fact that black women did not completely lose their weak hold on industrial positions reflected the segmentation of the labor force. Within specific geographical areas, certain jobs were earmarked not only for women, but also specifically for white or black or (in the Southwest) Hispanic women.

31Differentials in earnings, hours, and working conditions mirrored these various forms of segregation. For example, nationwide, black women earned twenty-three cents, and white women sixty-one cents, for every dollar earned by a white male. In Texas factories, the weekly wages of white women were $7.45, while Mexican women took home $5.40 and black women only $3.75. Comparing the hours of Florida female factory employees in 1930, the Women’s Bureau found that black women outnumbered white in commercial laundries and certain food processing plants, and that they took shorter lunch hours and received about one-half the pay compared to white women industrial workers in general. In some establishments, a black woman’s age and weekly hours were inversely related to her compensation; in other words, these employees were actually penalized for their experience and exceptionally long work week. Commenting on the low wages of fifteen to twenty-five cents per hour, and high productivity of southern tobacco stemmers (a traditional black female occupation), one government investigator noted sarcastically in 1934 that employers complained so much about the women’s work habits that “it would seem that it was a charity to employ them, unless one remembered the thousands of pounds of tobacco that they were stemming and sorting.”

32A sustained demand for their product through the early 1930s convinced tobacco manufacturers that it was they who presided over a truly “depression-proof” industry. Yet employers sought to press their economic advantage by imposing additional demands on workers who had no viable alternatives. Federally established minimum-wage guidelines exacerbated this trend. Stemming machines replaced some laborers and placed added strains on others, as if the constant heat, humidity, and stench of the workplace were not enough to make the job nearly unbearable. Interviewed by government officials, one black woman “described herself as crying at the machines because she could not quit in the face of high unemployment.”

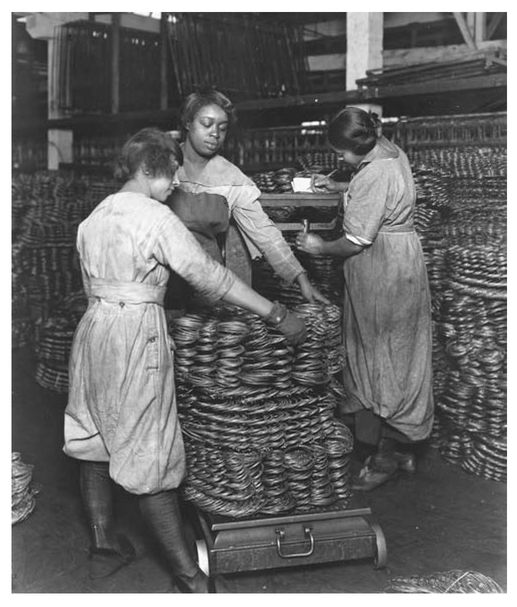

33Conditions were no better in other kinds of establishments characterized by high proportions of black women workers. Commercial laundry employees in New York City toiled fifty hours each week and “it was speed up, speed up, eating lunch on the fly” (that is, while they worked). Those in the starching department stood for ten hours each day “sticking their hands into almost-boiling starch.” Complaints to the boss provoked a thinly veiled warning: “There ain’t many places paying ten dollars a week now, Evie.” The description of one black laundry press operator, published in a 1936 Women’s Bureau report, would have seemed to verge on caricature had it not so accurately illustrated the deplorable work experience of so many women in need: The worker, who had only one leg, leaned on her crutches to depress the foot pedal, throughout the long, steamy day. (The garment industry reserved the position of presser for black women because of the intense heat and because the work required “unusual strength and endurance.”) Burlap bag makers inhaled dirt and lint as a routine part of their job. Meatpacking and slaughtering plants kept black women in the offal and chitterling departments, which were cold, wet, and “vile smelling.”

34This social division of labor was not new to American commercial establishments; the specific tasks assigned to black women had remained the same since they first entered northern factories in the World War I era. By the 1930s, however, it became clear that not only did individual positions lack advancement possibilities, but some jobs themselves (like those of tobacco stemmers) were well on the way to obsolescence. At the same time, federal child-labor legislation enacted as part of the New Deal necessitated the prolonged participation of mothers in the paid labor force. In North Carolina, laws restricting the labor of children under sixteen years of age meant that women often had to replace their offspring in the tobacco factories if families were to make ends meet, since two-thirds of all black households required the income of more than one worker. Under these circumstances the younger a woman’s children, the more likely that she would have to seek and retain gainful employment.

35Because of the nature of their jobs, many black female industrial employees derived no benefits from New Deal wage and hour legislation. Even when black women came under federal guidelines, they did not necessarily enjoy improved wages or conditions. Voluntary National Recovery Administration (NRA) minimum-wage codes set on an industry-wide basis institutionalized a variety of forms of discrimination (they were declared unconstitutional in 1935); workers received more or less pay depending upon their gender, “race,” and geographical location—North-South and rural-urban. The NRA respected prevailing wage differentials that blatantly discriminated against blacks, women, southerners, and rural workers. Thus the black female industrial workers concentrated in southern commercial laundries and tobacco plants made the very lowest wages sanctioned by the NRA. The arbitrary distinctions enshrined by the codes at times led to gross inequities even between groups of black women within the same industry. Tobacco stemmers who worked in commercial factories made a median hourly wage of twenty-five to twenty-seven cents, but those who performed the same tasks in dealers’ establishments (not covered by the NRA) earned only half that much, and usually no more than $6.55 for a fifty-five-hour week.

36In most cases employers found ways to circumvent minimum-wage-maximum-hours legislation that would have had a favorable impact on workers in general and black women in particular. Some steam laundries applied for and received exemptions from the codes on the basis of “labor scarcity” in the industry. Other employers reduced their hours and enforced speed-ups so that their employees would produce the same amount and take home the same weekly paycheck. If pressed on the issue, employers would fire their black women workers and either make do without them or replace them with machines. However, NRA codes ranked as a secondary factor in the displacement of black women; white competition played a much more important role in the process, simply because private industry failed to adhere to the voluntary standards in a way that would have made them effective. In any case, passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which made wage and hours standards mandatory, hardly solved the problem. For example, tobacco companies regarded the act as an incentive to mechanize the stemming operation that black women had traditionally performed by hand.

37The NRA’s Section 7(a) and the Wagner Act had a much less ambiguous impact on the black women they directly affected. These two measures in particular spurred collective action by guaranteeing workers the right to organize and bargain collectively with their employers for the first time in American history. With the implicit backing of the federal government, laborers struggled to revive dormant unions and create new ones equal to the times. Nevertheless, looking ahead to World War II and beyond, it is clear that at least some unions organized blacks out of temporary expediency and not out of principled conviction; the fact that white labor leaders failed to challenge a discriminatory division of labor within their own industries reveals that even black union members would remain in the lowest paying jobs, uniquely vulnerable to layoffs and speed-ups alike.

38During the Depression, the American Federation of Labor persisted in organizing workers on the basis of their skills and pursued a less than aggressive policy in attracting and keeping black members. The history of the Tobacco Workers International Union (TWIU) in Durham, North Carolina, reveals the potentially divisive effects of the AFL’s policies on a workforce composed of women and men, blacks and whites (locals organized their members according to task and then segregated them by skin color and gender). When the TWIU won a major strike against Liggett & Myers in June 1939, the company promptly installed machines in the stemming department, fired a large number of black women, and, for those who remained, cut back the number of workdays to four a week. The union readily sacrificed this group of workers to secure a contract. Annie Mack Barbee, a former L&M worker, spoke for other black women when she recalled, “The very day we quit working up there, here come the machines . . . Here come the machines and the white man was up there putting up signs for the bathrooms—‘White Only’ . . . I didn’t get anything from Liggett & Myers . . . [T]he mass of black women didn’t get a whole lot of nothing from them.”

39What few gains the AFL did make in organizing blacks and whites came at least partly out of a sense of competition with its rebellious stepchild, the Congress of Industrial Organizations, which broke from the parent body in 1935. The CIO waged a series of pitched battles against recalcitrant employers in the steel, auto, and rubber industries, and its emphasis on industry-wide organizing provided a dramatic contrast to the AFL’s exclusivity. The CIO’s major campaigns spilled over into smaller businesses as well, and by 1940 it boasted 3.6 million members. Many of the 800,000 female union members in 1940 belonged to CIO affiliates.

40The International Ladies Garment Workers Union (which joined the CIO later in the decade) had its “racial” consciousness raised during the early 1930s. Mary Sweet, a black presser in the Boston garment industry, refused to participate in a 1933 strike organized by the ILGWU because it would not admit her as a member. Upon the successful completion of the strike, she noted, “Our shop signed a union agreement and the women pressers had to get out. They gave us four months to find other jobs.” However, later the ILGWU asked her to help organize the black women who often served as strikebreakers. She attributed the local’s new openness to orders received from headquarters in New York City, where a coalition of unions had formed the Negro Labor Committee to further the cause of black workers. By 1934 ILGWU locals in New York City, Boston, Chicago, and Philadelphia were integrated and some shops even boasted black “chairladies.” The black dress-pressers in New York’s Local 60 were among the best-paid women in Harlem, with wages of $45 to $50 for a thirty-five-hour week.

41The Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America not only welcomed black women into its ranks, it also spawned an affiliate, the United Laundry Workers (ULW), one of the most successful integrated unions in the 1930s. The ULW had 14,000 members in 1937, many of them black women. Evelyn Macon credited her own newfound militancy to a boss’s order that she and other women in a New York laundry stop singing the spirituals that had distracted them from their slavelike conditions. He “said that was too much pleasure to have while working for his money, and the singing was cut out.” As a result, she said, the workers then had an opportunity to contemplate their “miserable lot”—“that was where the boss made his mistake.” After a few weeks, persistent picketing, combined with less than effective strikebreakers, helped them get a CIO contract, with a thirty-five-cent minimum wage and a five-day week.

42At least some black communities threw their support behind union activities for the first time, impressed with the relative openness of CIO policies and with the uncompromisingly egalitarian rhetoric of the Communist Party. (In fact the Communists conducted several dramatic, successful organizing drives that made full use of black women’s leadership abilities, including the St. Louis nutpickers’ strike against “Boss Funsten” in 1933.) The CIO represented a new era in the history of black women, and its significance went far beyond the number who were members. Black women served to advance the cause of workers’ rights by supporting their husbands’ decision to join and stick by a union. In some cases they helped to form women’s auxiliaries, like the one associated with the Steel Workers Organizing Committee. The Women’s Emergency Brigade played a pivotal role in the 1937 General Motors sit-down strike conducted by the United Automobile Workers in Flint, Michigan. And finally, black wives and mothers benefited materially whenever their husbands and sons won wage increases or job security through their participation in CIO-affiliated unions.

43Nevertheless, the CIO won its greatest gains for blacks who already had jobs, rather than for those systematically excluded from certain kinds of work, prompting one historian to call its policies “aracist.” Especially large and cohesive communities formed their own advocacy groups (like the Harlem Labor Union) when white-dominated locals called upon black support and used it to win jobs for white workers exclusively. Moreover, affiliates’ opportunistic approach toward black women workers would become abundantly clear at the end of World War II, when the interests of black men and white and black women were ignored by many white men in the union hierarchy, from shop-floor stewards to leaders of the internationals. If the CIO promoted a “culture of unity,” that culture was a product of the Great Depression, rather than a long-term, principled commitment to full equality for black men and women workers.

44The success of industrial unions during the 1930s benefited only a small percentage of black workers overall. In contrast, black working women in general found strong advocates from several quarters during the Great Depression, groups that focused on a number of strategies, including vocational training, political advocacy, and organized protests. For example, in founding the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) in 1935, Mary McLeod Bethune, a member of FDR’s “Black Cabinet,” brought together twenty-eight black women leaders, themselves heads of national groups, to form “an organization of organizations.” The initial purpose of this new umbrella group was to coordinate the drive to place black women in federal agencies, but it soon expanded its reach. Bethune, with her stress on the role of government action, and her willingness to embrace the Democratic Party as an agent of change, presented a contrast with Mary Church Terrell, first president of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, who had supported a philosophy of “uplift” and the Republican Party. The NCNW sought to make alliances with other groups, such as the League of Women Voters, and to challenge discriminatory hiring—including the requirement that job applicants submit a photo of themselves—in federal agencies. The group also decried the exemption of domestics and agricultural workers from Social Security and other landmark pieces of social-welfare legislation. Complementing the work of the NCNW was the Ladies Auxiliary of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters—1,500 female relatives of the porters, who came together from scattered regional councils in 1938 to form a national organization. The auxiliary promoted the unionization of black men and women, in contrast to what it considered the middle-class professional bias of the NCNW. Also active were local groups, such as the Harlem branch of the Young Women’s Christian Association, which sponsored a variety of services for black working women, including a trade school and nursing courses in an effort to open the way for more black secretaries and nurses. Yet the barriers to full and equal hiring policies remained seemingly insurmountable. In 1935, Cecelia Cabaniss Saunders, executive director of the Harlem Y, testified before a mayoral Commission on Conditions in Harlem, describing the intransigence of the local telephone company: “We asked for employment of telephone operators at least in the Harlem area. They objected to the voices of the colored girls. We said we had someone with a lovely voice. We asked to have her tried out. The telephone company didn’t agree to that. These girls were reared in New York. No one would know whether they were colored or white.” Faced with such blatant prejudice, the appeals of black women’s advocacy groups would falter in the absence of federal mandates and the legal backing to enforce them.

45

Women’s Wage Work in the Black Community

Black women employed outside of agriculture, domestic labor, and industry represented a diversity of work experiences, not all of which lend themselves to close historical scrutiny. For example, the numbers racket, which offered the hope to many poor people that they could “gain through luck what had been denied them through labor,” served as a major employer in some black communities. During the 1930s, the Chicago numbers business sustained as many as two hundred employees, at least some of them women in white-collar jobs, and boasted a $26,000 weekly payroll. Predictably, though, legitimate businesses operated by blacks suffered losses reflecting their clients’ reduced circumstances; between 1929 and 1935 the sales of black-owned retail stores dropped by 51.6 percent, compared to a decline in the nation’s overall payroll of 32.5 percent. As healers, religious leaders, and entrepreneurs, black women still offered their services to friends and neighbors, but in most cases they had to adjust their fees to bring them in line with the realities of depression life.

46Midwives and older women knowledgeable in folk medicine continued to occupy an honored place in African American culture. Their techniques represented an irresistible mixture of common-sense psychology and time-honored tradition. In the 1930s some midwives still “put a sharp knife under the pillow” of a woman in labor; “they say that cuts the pain.” In Florida, Izzelly Haines prescribed concoctions of onions, gin, boiled mud, and worm-infested “dauber nests” to hasten the expulsion of the afterbirth. Southern midwives delivered up to 85 percent of all babies in parts of that region during the 1930s. Certainly these women were relatively affordable; in Texas even rural doctors charged up to $75 for attending a woman in labor, while the rate for a midwife was usually less than $10. Ultimately, however, “grannies” depended upon their patients for their own well-being, more often than not adopting the attitude of Haines; in 1939, in response to an interviewer’s question, she noted, “As for pay, I takes whatever they give me.”

47The northern ghetto opened some opportunities for female religious leaders to exercise power in a formal sense. Like midwives and grannies, female preachers served as “spiritual advisors” to their followers and as links to a southern past. But their style tended to be flamboyant as they competed with others for storefront “consumers,” their words full of urgency as they exhorted worshippers to confront a crisis born of faithlessness more than economic depression. Here was Harlem’s Mother Horn, attired in silk and presiding over a congregation of four hundred, a “dynamo of action” during old-time fundamentalist services in her Pentacostal sanctuary; or Elder Lucy Smith, “elderly, corpulent, dark-skinned and maternal,” who during the 1930s transformed her tiny meeting place into the prosperous Church of All Nations in Chicago’s Bronzeville. Lucy Smith began her career, she later recalled, “with giving advice to folks in my neighborhood.” But unlike the vast majority of female “confessors,” she had gone on to parlay into worldly success her ability to heal “all kinds of sores and pains of the body and of the mind.”

48More conventional forms of female employment offered limited opportunities for black women during the Great Depression. Only a few nurses found jobs in local hospitals; instead, increasingly those with nursing credentials sought work in public-health agencies sponsored by cities or states. Henrietta Smith Chisholm graduated from Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C., a degree that launched her on a career in public health in the early 1930s. Recalled Smith Chisholm, “Freedmen’s was the only hospital at which Negro nurses could work.” Like teachers, nurses benefited from specialized training that allowed them to earn steadier wages above those of a domestic, and at the same time gain the satisfaction of serving the community, characterized as it was by rigid patterns of segregation. Smith Chisholm noted, “I liked public health very much. This was brand new. . . . [It] was the right field for me because I enjoyed it because it wasn’t all morbidity—you felt like you were giving people help before they got into trouble. We hoped we were. I especially liked the infant and maternity program and worked mostly in infant, maternal, and child welfare clinics.” Her annual salary of $1,620 placed her among the best-paid black professionals during the Depression.

49As black businesses closed their doors or laid off employees, and white-owned ghetto establishments adamantly refused to hire black clerks, secretaries, or salespeople, black men and women launched “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaigns. The struggles in Chicago, Baltimore, Washington, Detroit, Harlem, and Cleveland relied on boycotts sponsored by neighborhood “Housewives Leagues,” whose members took their grocery and clothes shopping elsewhere, or did without, rather than patronize all-white stores. These campaigns captured an estimated 75,000 new jobs for blacks during the Depression decade, and together they had an economic impact comparable to that of the CIO in its organizing efforts, and second only to government jobs as a new source of openings. In the process, women’s energies at the grassroots level were harnessed and given explicit political expression.

50Efforts to win jobs for Harlem residents revealed how the Communist Party in the North both fulfilled and fell short of community expectations during the Depression. Black people embraced the party when it responded to their needs for jobs and better housing—a conditional form of support that inspired mixed feelings in party members. One official later recalled that many of the poorer black women attracted to the organization needed work, “and we had to say to them: ‘The Party is not a sewing club’” (referring to government-sponsored work projects). The party organized shop units among groups of women workers (like the nurses in Harlem hospitals) and helped to open a significant number of jobs for blacks in telephone and federal welfare offices. Yet despite its reliance on charismatic local leaders (including Bonita Williams and Rose Gauldens), it remained dominated by white men and aloof from the intense religious devotion of the black masses. Helen Cade Brehon, recalling her youth in Harlem, suggested that the party’s aloofness from the church also indicated that it “underestimated . . . the importance of our women in the Black community.”

51Women who relied upon public institutions and private businesses within their own neighborhoods for gainful employment during the Depression faced a double dilemma. The faltering enterprises operated by members of their own group needed fewer and fewer employees, while the federal government and white businessmen persisted in hiring whites for the other positions available. Only through collective action could black women and men win those coveted jobs that existed by virtue of their own patronage; the successful community boycotts of the 1930s would serve as a lesson for the next generation of black leaders—a lesson that revealed the economic and political power inherent in ordinary black housewives’ commitment to justice.

The Partisan and Ideological Politics of Public Works Projects

If the labor movement touched only a fraction of all black women workers, it of course offered little solace to the large numbers out of work. For jobless black mothers, wives, and daughters in rural areas and in the city, North and South, the federal government proved to be a most grudging employer of last resort. Indeed, there was good reason to suspect that, left to their own devices, public works administrators would merely reflect the preferences of employers in the private sector. More often—usually—officials used their power to help whites at the expense of blacks. At the same time, some New Deal programs presaged the affirmative action policies of the 1960s and beyond. In 1935 President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 7046, outlawing discrimination by the Works Progress Administration (WPA). In response, Crystal Bird Faucet, a black woman and head of Philadelphia’s Women’s and Professional Project of the WPA, unilaterally raised the quota limiting black women’s participation from one-third to one-half; as a result, three thousand black women, all former relief recipients, benefited from gainful employment. On another New Deal front, the Public Works Administration (PWA) took steps to ensure that local building projects hired black construction workers and that local housing projects awarded black tenants their fair share of units. These initiatives were especially significant in the North, where Democratic politicians had an incentive to appeal to likely black constituents, a consideration irrelevant in the South, where black voters remained systematically disfranchised.

52In assessing the impact of New Deal public works programs on black women, it is difficult at times to separate federal policy from local guidelines, prevailing national (white) public opinion from specific sectional biases. Southern sponsorship of work relief is especially revealing, for white Democrats found themselves in a quandary of sorts as they sought to take advantage of black women’s “free” labor and at the same time cooperate with the private employers of field-hands and domestic servants. (Of course the boundary between public and private employers frequently blurred whenever local administrators relied on black labor in their own homes or fields.) Ultimately these whites were able to use federal funds provided by the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (1933-1935) and the WPA (1935-1941) to reinforce traditional social divisions of labor based on class considerations and racial and gender ideologies.

53The various works programs of the 1930s discriminated against white women and all blacks in terms of the number and kinds of jobs offered to applicants. Policymakers, bureaucrats, and social workers believed that jobs constituted a more dignified and respectable form of aid than direct relief (workers in general agreed) and that employment should therefore benefit men more than women, whites more than blacks. Most projects created heavy construction-type work for men on the assumption that priority would be given to the primary breadwinner in needy families. This policy ignored the wage-earning role of both single and married women and, in particular, severely limited the opportunities for female household heads. As part of his first annual report on “Negro Project Workers” in the WPA, Alfred Edgar Smith, an agency administrative assistant, noted that, during the year, “Some Negro women family heads subsisted on irregular issues of surplus commodities or not at all because of scarcity of projects for their employment.” Between 1935 and 1941, less than 20 percent of all WPA workers were female, and only about 3 percent of all WPA workers were black women, although a higher—and in the South, much higher—proportion of all female family heads on relief were black.

54Few well-educated black women received job assignments commensurate with their talents or professional training. Margaret Walker, Zora Neale Hurston, and Catherine Dunham worked on the Federal Writers Project, and Hurston served as head of the black folklore unit of the Florida FWP from 1938 to 1939. A small number of black women benefited from relatively prestigious social work and clerical positions. For example, the large Washington, D.C., black population was in a favorable geographical location, near the seat of power; in 1938, 162 black women WPA employees were working as clerks and seventy-three as typists. Elsewhere, a handful served as supervisors for segregated projects, but like Jannie F. Simms of Louisa County, Virginia, they often had to rely on direct intervention from sympathetic federal officials in order to get and keep their jobs. Simms owed her appointment as “Garden Director for the Subsistence Garden of Louisa County, among colored people” to Forrester B. Washington, director of Negro work for the FERA. The WPA received well-deserved criticism for reducing skilled and well-educated blacks of both genders to menial labor.

55Over one-half of all women employed by the WPA worked on sewing projects, which required local sponsors to donate materials. In the absence of such a sponsor, black women in impoverished communities like Madison County, Alabama, found all WPA opportunities closed to them. Moreover, the administration of so-called sewing-room “tests” served to reduce the number of eligible black women applicants. Another program for women, “household demonstration training,” provided instruction in domestic skills and supposedly helped to put WPA workers at a competitive advantage in the private job market. In fact, project managers often systematically excluded black women; in 1937 “only white women in St. Louis, Missouri, and white and Mexican women in San Antonio, Texas, were being trained in the Household Training Centers,” while resources for black women remained suspended in a state of “contemplation.” In any case it is unlikely that the few black women who received a certificate from short-term WPA household training programs found their chances for private employment markedly improved.

56Nevertheless, black women preferred public jobs because they usually paid more and required shorter hours compared to private work. Therefore, many southern whites objected to aid of any kind—cash or jobs—that would “take the pressure off the Negro families to seek employment on the farms or in the white households,” under the assumption that the “standard of relief offered would compete too favorably with the local living standards of the Negroes.” Sensitive to these criticisms, southern WPA officials routinely engaged in “clever manipulations” to reduce the wages to which black women were entitled. For example, in response to federally authorized pay hikes, they “reclassified downward” workers so that a “‘raise’ plus their new wages merely equaled their old wages.” New Orleans officials went so far as to allow “two Negro women to share one WPA salary, so that instead of one worker receiving about $39.00 [monthly], two workers received about $19.50 each.” Nevertheless, even this small amount was more than black women could earn as servants.

57Just as the private sector reserved certain kinds of work exclusively for black women, so WPA supervisors created special projects limited to either blacks or whites. For example, St. Louis industrial training programs remained closed to black women because they lacked the requisite “factory experience.” In the South, only black women found employment on the euphemistically titled “Beautification” projects. White administrators in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Virginia, and Texas justified these projects by arguing that they simply required the women involved to do “landscaping, [and] wild flower planting . . . pointing out that this is the only suitable form of employment for these Negro women, since they cannot sew, and ‘cannot expect to get any other type of work when they return to private industry.’” Critics of these discriminatory policies charged that black women, unlike their white counterparts, were forced to perform “men’s jobs” outdoors and that some even had to wear a special uniform “stamping them as some sort of convicts.” From Florence, South Carolina, in February 1936 came a complaint from a local physician that revealed the true nature of the projects in question: “The Beautification Project appears to be ‘For Negro Women Only.’ This project is not what its name implies, but rather a type of work that should be assigned to men. Women are worked in ‘gangs’ in connection with the City’s dump pile, incinerator and ditch piles. Illnesses traced to such exposure as these women must face do not entitle them to medical aid at the expense of the WPA.” In Fayetteville, North Carolina, officials opened a “cleaning project” for black women and at the same time disbanded their sewing group. Thurgood Marshall, assistant special counsel for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, reported that WPA officials transported southern black women workers in open trucks during foul weather and “required [them] to do regular scouring and cleaning work as well as painting and chopping grass at the white schools.” Black female construction workers in Jackson, Mississippi, toiled under the supervision of guards armed with guns. In Savannah, a black mother sent a letter to FDR and told him that white women received indoor assignments while “we are in the wood cutting down three [sic] and digging them up by the roots with grub hoe an pick ax[;] these thing aint fare.”

58At times WPA officials (and welfare administrators in general) served as recruiting agents for local planters who complained that they could not find enough hands to pick cotton and worm tobacco plants. A “Workers Council for Colored” representative in Raleigh, North Carolina, denounced the recent dismissal of all black female household heads from federal jobs programs in October 1937; Mary Albright wrote to Harry Hopkins that the WPA wanted to “make us take other jobs . . . and white women were hired & sent for & given places that colored women was made to leave or quit.” These “other jobs” included forcing mothers to stand in open trucks twenty miles each way, twice a day, to work in tobacco fields “beginning 6 to 6:30 a.m. till 7:30 & 8:00 p.m.”—all for “such poor wages” that they could not possibly support their families. In Oklahoma, a WPA official closed a black women’s work project upon the appearance of “an abundant cotton crop which is in full picking flower.” By way of explanation, he wrote to his Washington supervisors that “these women are perfectly able to do this kind of work and there is plenty of work to do.” Alfred Edgar Smith noted in his report for 1938 that black women in the urban and rural South had been denied WPA jobs because they were told “You can find work in kitchens” or “You can find work if you look for it.” In response to one black woman’s request for aid, a Mississippi official ordered her to “go hunt washings.”

59Because they wielded a certain amount of political influence, black women and men in the North frequently received their proportionate share of Works Progress Administration jobs; in fact, this form of employment “provided an economic floor for the whole black community in the 1930s.” Yet the actions of local federal administrators in the South indicated how little those white men’s attitudes toward black female labor had changed since the days of slavery. Whether they were plantation owners or government officials, they saw black wives and mothers chiefly as domestic servants or manual laborers, outside the pale of the (white) gendered division of labor. During the Depression, southern administrators had access for the first time to large amounts of federal money, which they used on a large scale to preserve the fundamental inequalities in the former Confederate states.

60Domestics’ daughters might have thrilled to the galvanizing power of a Mother Horn, or marveled over photographs of Mary McLeod Bethune in her Washington, D.C., office. But it was the entertainment field that fueled the dreams of black girls who yearned for a life’s work of glamour and triumph. As the keepers of the flame of African American musical tradition, a handful of black female singers were rewarded by listeners both black and white in clubs or at home in front of the radio or Victrola, because, in the words of writer Richard Wright, “Those who deny us are willing to sing our songs.” Hollywood for the most part reinforced stereotypes of black women as mammies, scatterbrains, or tragic mulattoes. Yet the recording industry gave expression to a full range of artistic styles—from the earth-moving spirituals of Mahalia Jackson, to Ella Fitzgerald’s punchy jazz, Lena Horne’s sultry pops, and the worldly blues of Billie Holiday and Bessie Smith. On Easter Sunday 1939, the contralto opera singer Marian Anderson, a granddaughter of former slaves, transfixed the nation with her concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. When the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to let Anderson sing in Constitution Hall in that city—they had a “white artists only” policy—Eleanor Roosevelt resigned her membership in the group and arranged for Anderson to perform at the memorial, which she did to great acclaim. In the public spotlight, surrounded by musicians and their managers, famous black women singers beckoned listeners away from the routine of the white woman’s kitchen and into a glittering world of public adulation. Yet in a song like Bessie Smith’s “Washwoman’s Blues,” the cycle of black women’s work came full circle, as the successful singer reminded herself of the fate from which luck and talent had rescued her. A wailing clarinet serenades the weary laundress: “All day long I’m slavin’ / All day long I’m bustin’ suds / Gee my hands are tired washin’ out these dirty duds.” The rhythm of the piece is slow, laborious, evocative of the work itself. In effect, the song lifted one woman’s sorrows out of their time and place and transformed them into a universal lament of great dignity and beauty.