10

New Hope

Assessing Episode IV (1977)

Few films are as venerated—or as vilified—as Star Wars. Its supporters revere it as a model of escapist filmmaking and an exhilarating, inspirational reframing of ancient myth. Writing for The Atlantic in 2011, critic Colin Fleming called Star Wars “the galactic gold standard” and argued that “you can put [it] alongside The Searchers, Bride of Frankenstein, or The Wizard of Oz as an American film masterpiece.” Star Wars regularly finishes at or near the top of the poll when fans are asked to name the greatest movies ever made. On the other hand, Star Wars’ detractors revile the picture, arguing that it served as a catalyst for the dumbing down of popular culture in general and Hollywood in particular. John Simon, film critic for the National Review, summed up the complaints of many Star Wars haters during an appearance on ABC’s Nightline following the release of Return of the Jedi in 1983. “Obviously, let’s face it, they [the Star Wars films] are for children, or for childish adults,” Simon said. “They are not for adult mentalities.” He bemoaned the films’ reliance on special effects, dismissing the series as “a technological whirligig” with “lousy actors,” “ghastly dialogue,” “terrible plotting,” and “miserable characterization.” Opinions between these two camps are so sharply divided that it’s hard to believe these people watched the same movie. Yet the qualities that made Star Wars such a popular sensation are, in large part, the same ones that invited vehement critical backlash.

Images in Motion

They call them motion pictures for a reason. First and foremost among the reasons why Star Wars enchanted moviegoers in 1977 was that it put spectacular pictures in thrilling motion. The film played to all of director George Lucas’ strengths: pictorial composition, rhythmic film editing, innovative sound design, and the wedding of images with music. His dexterity in these areas had been apparent as far back as his student films at USC and was displayed in THX 1138 and American Graffiti. But Star Wars enabled Lucas to apply these skills in conjunction with the next-generation visual artistry of Industrial Light & Magic and the stirring music of John Williams. The results were extraordinary. Nothing had ever looked or moved quite like it.

Audiences in 1977 had never seen anything quite like the dogfighting spaceships in Star Wars.

The film has become so iconic, and has been so frequently copied, that it may be difficult at this distance to appreciate how dazzling a visual experience Star Wars was when it premiered. When the massive Star Destroyer rumbled across the screen, jaws literally dropped—not only because the shot was beautifully rendered but because it immediately drew viewers into the story. The Destroyer roared past with blasters flaring in hot pursuit of Princess Leia’s spaceship, instilling a sense of urgency and establishing that (unlike, say, 2001: A Space Odyssey) Star Wars would value action as much as image. Crisp editing—the picture cuts almost mercilessly from one eye-popping scene to the next—kept the picture crackling with energy. Although not particularly fast by today’s standards, Star Wars was edited at a breakneck pace for a 1977 film. Viewers were held in thrall by a succession of spellbinding and visually arresting sequences, including the Mos Eisley cantina interlude, Leia’s rescue from the Death Star, and the epic space battles. Beyond these showpieces, however, the narrative is punctuated with still more lovely shots— for example, Luke posed against the rugged landscape of Tatooine as the planet’s twin suns sink into the horizon. This moment, like most of the film’s other most powerful scenes, is greatly enhanced by Williams’ evocative score.

The sheer visual power of Star Wars, in and of itself, would have made the film a can’t-miss event for many moviegoers. Some critics looked askance at ILM’s technical wizardry, or at least at the way Lucas so thoroughly integrated it into the film. “Special effects are like the tail of the dog, which should not wag the whole animal,” Simon groused. “When you have a film that’s 90 percent special effects you might just as well be watching an animated cartoon.” But what the detractors failed to appreciate was the virtuosity with which those effects were employed—how seamlessly integrated and fluidly edited they were, and how beautifully they were mated with Williams’ music. Later filmmakers would find it simpler to match ILM’s work than Lucas’. Take, for instance, Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), which offered equally impressive visuals but remained a turgid, tedious misfire.

Story and Performance

In other respects, as Lucas readily admits, Star Wars was less successful. “From a technical point of view—my own point of view—I don’t think it’s altogether that well-made a movie,” the director told Starlog magazine in 1981. The skeptics are correct that Star Wars is not a work of sublime artistry, subtlety, or depth. But it wasn’t meant to be. It’s the grandchild of Flash Gordon, not Citizen Kane. Judged apples-to-apples with its forebears, Star Wars looks very good indeed. “One of Mr. Lucas’ particular achievements is the manner in which he is able to recall the tackiness of the old comic strips and serials he loves without making a movie that is, itself, tacky,” wrote Vincent Canby, film critic for the New York Times, in his review of the film.

Star Wars instantly became the new standard-bearer for spacefaring action-adventure. Lucas took the muscle from vintage sci-fi serials and discarded the fat and connective tissues. Star Wars plays like a highlight reel, rushing headlong from one thrilling incident to the next, devil take the exposition. Niceties like scientific plausibility were beside the point. Devising a clever plot and sketching fully realized characters wasn’t part of the calculus either, which is why Lucas had such difficulty writing the screenplay. His script is lumpy, with holes in story logic, thinly sketched characters, and tin-eared dialogue. But the story merely serves as a framework on which to hang the picture’s breathtaking set pieces. The Millennium Falcon’s battle with the TIE fighters, for instance, was one of Lucas’ primary inspirations for the entire project. While atypical, this manner of constructing a screenplay was hardly unprecedented or invalid. Alfred Hitchcock often worked the same way. Hitch constructed the rest of North by Northwest (1959) around two showstopping scenes—the crop duster attack and the Mount Rushmore finale.

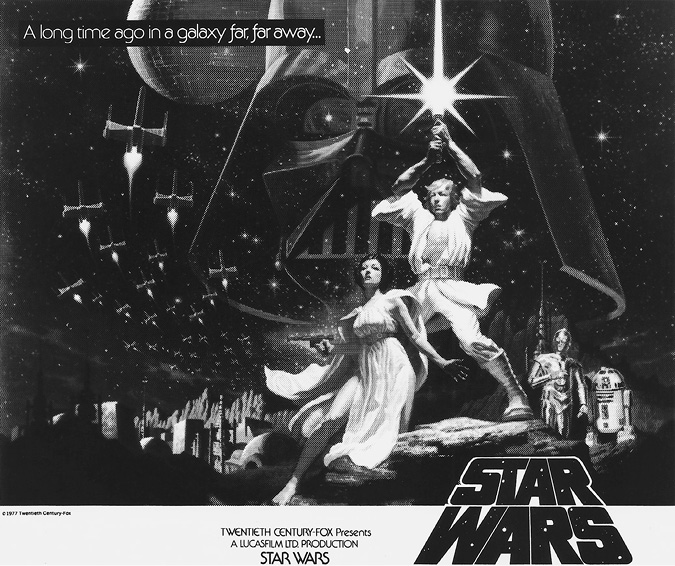

This newspaper ad slick was based on the original, now-iconic, one-sheet movie poster that announced Star Wars.

Critics also overstate the deficiencies of the film’s cast. Mark Hamill, Harrison Ford, and Carrie Fisher may not deliver finely nuanced portrayals, but they fully inhabit their characters, which is an accomplishment given Lucas’ frequently awkward dialogue. It may represent a triumph of casting more than performance, but Hamill the earnest naïf, Ford the skeptic, and Fisher the Hollywood princess serve the film well and have wonderful chemistry as an ensemble. It’s impossible to imagine anyone else playing Luke Skywalker, Han Solo, or Leia Organa.

As Obi-Wan Kenobi, Sir Alec Guinness doesn’t approach his finest work, but he easily tosses off the movie’s best performance. Guinness anchors Star Wars, lending dignity and credibility to the universe Lucas is creating, and his presence enhances the work of all his cast mates. His matter-of-fact interactions with C-3PO, R2-D2, and Chewbacca help sell the idea that Laurel & Hardy robots and giant “walking carpets” are commonplace things. As Threepio, Anthony Daniels delivers another of the film’s best performances, remarkable for both its distinctive physicality and his delightful comedic delivery. The actor’s work is even more impressive because it was accomplished under almost unendurable circumstances, especially in Tunisia. The composite performance of David Prowse and James Earl Jones as Darth Vader is also startlingly effective. Vader became the breakout character of the film, even though he was on-screen for just 12 of the movie’s (original) 121 minutes. Peter Cushing shines in his brief appearance as Grand Moff Tarkin, playing against type as an icy, pitiless villain. (In his horror films, Cushing was most often cast in sympathetic roles.) Even Peter Mayhew, buried under fur and makeup as Chewbacca, brings vitality and personality to what could have been a thankless part, through his body language and wonderfully expressive eyes.

The Future of the Future

Heading into the summer of 1977, Twentieth Century-Fox executives figured they had a sure-fire science fiction blockbuster in the bag—but it wasn’t Star Wars. It was Damnation Alley, a postapocalyptic thriller based on an acclaimed novel by Hugo- and Nebula-winning author Roger Zelazny, starring rising heartthrob Jan-Michael Vincent and the stalwart George Peppard. Helming the production was Jack Smight, a reliable hitmaker whose previous two films—Airport 1975 (1975) and Midway (1976)—had earned a combined $90 million, both ranking among the ten highest-grossing films of their year. Yet, while Star Wars did record business, Damnation Alley, which cost $17 million ($6 million more than Star Wars) failed to recover its production expenses. Damnation Alley failed, primarily, because it simply isn’t a very good movie. Its screenplay, which veered away from the source material, is inane (Zelazny disowned the film), and its visual effects are clumsy. But there was something larger working against the picture.

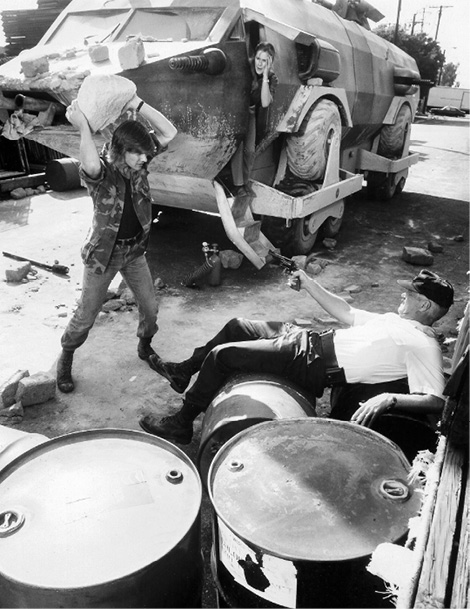

Jan-Michael Vincent, left (with rock), and George Peppard, right (with pistol), costarred with Dominique Sanda (background) in Damnation Alley, a postapocalyptic thriller that Twentieth Century-Fox expected to be a summer blockbuster. Released in the wake of Star Wars, Damnation Alley flopped.

The release of Damnation Alley, originally slated for a month after Star Wars, was postponed so it wouldn’t compete with Fox’s surprise smash. By the time Damnation Alley finally appeared in late October, however, audience tastes had changed. Following Star Wars, Damnation Alley seemed hopelessly out of date—and not just because its visual effects were laughable. Damnation Alley belonged to an earlier era of screen SF, one that had reached an abrupt end.

The renowned 2001 had earned the genre new critical acceptance, but with respectability came a desire by filmmakers and an expectation from audiences that sci-fi cinema would approach serious issues (nuclear proliferation, pollution, overpopulation, rising violence, etc.) in serious ways. As a result, the major science fiction films of the early and middle 1970s were relentlessly downbeat and usually dystopian. These included No Blade of Grass (1970), A Clockwork Orange, The Omega Man, Silent Running (all 1971), Soylent Green (1973), and Rollerball (1975). Lucas’ THX 1138 (1971) was among the many smaller-budget films of the period to depict a grim future for humankind, along with pictures like Death Race 2000, A Boy and His Dog (both 1975), and others. Fox issued its fatalistic Planet of the Apes sequels and Andrei Tarkovsky made his dour Solaris (1971) during this era. Logan’s Run (1976), although presented as a lighthearted adventure, took place in a future where people are sentenced to die when they reach age thirty. Hollywood had seen the future, and it sucked. It was taken as a given in these films that life would only worsen as the decades and centuries wore on, and that some sort of apocalypse—nuclear, environmental, or political—was inevitable.

Star Wars changed the orbit of mainstream sci-fi. The major SF films released between Star Wars and Return of the Jedi (1978–83) were lighter in tone, with less emphasis on social messaging and greater investment in action-packed or horror-tinged thrills: Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978), Superman: The Movie (1978), Superman II (1980), Superman III (1983), Alien (1979), Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982), E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), and The Thing (1982). And that list omits the torrent of blatant Star Wars knockoffs that flooded theaters during those years (see Chapter 13). Even the dystopian pictures released during this era—such as Mad Max (1980), Escape from New York (1981), and Blade Runner (1982)—were less preachy and more adventure oriented. Issue-based “pure science fiction” films like those of the early 1970s grew increasingly rare. This stuck in the craw of some hardcore SF fans, who appreciated the more erudite, literary turn the genre had taken earlier in the decade. They resented Star Wars—which Lucas never claimed as true science fiction, usually referring to the movie as a “space fantasy”—for setting the genre back, intellectually.

It’s true enough Star Wars shoulders much of the responsibility for this radical shift in the tone and style of science fiction movies. Its unprecedented financial success—not only in terms of box office returns, but also in ancillary revenue streams such as merchandising and publishing—put dollar signs in the eyes of every executive in Hollywood. Rival studios immediately launched a frantic search for similarly exploitable properties. Pictures like Soylent Green weren’t what they were looking for. However, the extraordinary profitability of Star Wars didn’t create a change in moviegoers’ appetites; a change in moviegoers’ appetites enabled Star Wars to achieve its extraordinary profitability. It was simply the right film for its moment.

New Hope

The science fiction films of the early 1970s reflected their times, an era scarred by war, race riots, terrorism, a global energy crisis, and social and political upheavals of all sorts. In America, economic inflation, ongoing antiwar protests, more strident civil rights and “women’s liberation” movements, and growing ecological activism roiled the country, while the “credibility gap” of the Vietnam War years, followed by the Watergate scandal, created lingering mistrust of government and skepticism that the United States, as a nation, retained any sort of moral compass. Cynical films like M*A*S*H (1970), Chinatown (1974), Dog Day Afternoon (1975), and Network (1976) became major hits. Even the escapist entertainments of the era were relatively grim—disaster movies like Airport (1970) and The Poseidon Adventure (1972), and rogue cop films like Dirty Harry and The French Connection (both 1971).

By the late ’70s, however, audiences were growing weary of misery and cynicism. They wanted more upbeat fare, as the popular and critical success of Sylvester Stallone’s feel-good boxing drama Rocky signaled in 1976. All four of the 1977 blockbusters (Star Wars, Saturday Night Fever, Smokey and the Bandit, and Close Encounters of the Third Kind), like many earlier 1970s movies, featured corrupt, absent, ineffectual, or conspiratorial authority figures. But they also featured underdog everymen (and everywomen) who triumphed in the end. They were various types of escapist fantasy. Star Wars outdid the others because it offered something in addition to escape: reassurance.

Star Wars didn’t acquire the retronym A New Hope until its 1981 rerelease, when the Episode IV subtitle was added to the film. But it was a perfect name for the picture, since the new hope of the title could refer both to the triumph of the heretofore downtrodden rebels in the film and to the emotional invigoration the movie provided audiences. In an era (and a genre) rife with doom and gloom, Star Wars shined like a beacon of positivity. But this wasn’t the optimism of some literary science fiction, reflecting the conviction that new technologies could solve society’s problems. Nor was it anything like Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry’s belief in the perfectibility of the human species. In fact, it wasn’t anything new or forward-looking at all.

Although on the surface, the two films could hardly seem more different, Star Wars stemmed from the same impulse that led Lucas to create American Graffiti. “This is my next movie after American Graffiti and, in a way, the subject and everything . . . is the very same subject that American Graffiti is about,” Lucas said in his audio commentary for Star Wars.

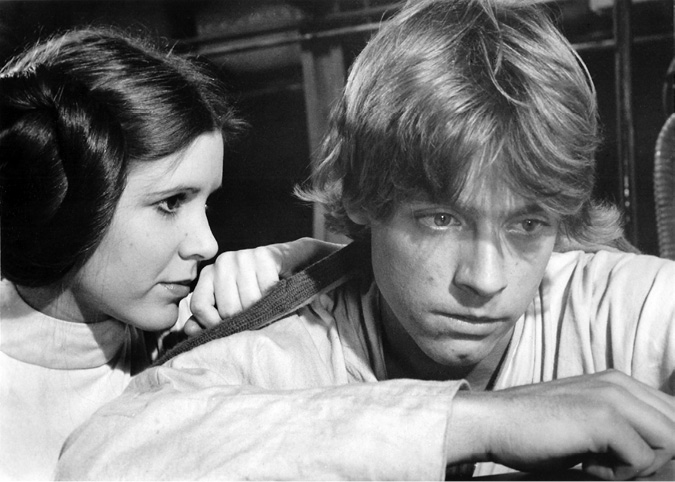

Tender character moments generally aren’t a strength of Star Wars, but the movie features one when Princess Leia (Carrie Fisher) comforts Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) following the death of Ben Kenobi.

In 1974, Lucas told Film Quarterly interviewer Stephen Farber that the defeatist attitude of THX had been a mistake. “All that movie did was make people more pessimistic, more depressed, and less willing to get involved in trying to make the world better,” Lucas said. “So I decided that this time [with Graffiti] I would make a more optimistic film that makes people feel positive about their fellow human beings.” Graffiti transported viewers back to 1962. It was the year America became involved in the Vietnamese civil war, and the beginning of the end for America’s postwar economic boom, although few people recognized those things at the time. From a mid-’70s perspective, 1962 could be remembered as the last gasp of the Good Old Days, before President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, before America began to rip itself apart. Star Wars reflected the same 1962 worldview as American Graffiti, inspired as it was by the kinds of movies that the kids in American Graffiti would have watched in movie theaters or on television, the kinds of movies Lucas watched when he was one of those Graffiti kids.

In ’62, straightforward, good-guys-versus-bad-guys Westerns, war movies, and adventure stories didn’t seem corny or ironic. “My main reason for making it [Star Wars] was to give young people an honest, wholesome fantasy life, the kind my generation had,” Lucas told Time magazine in 1977. “We had Westerns, pirate movies, all kinds of great things. Now they have The Six Million Dollar Man and Kojak. Where are the romance, the adventure, and the fun that used to be in practically every movie made?” Indeed, if Star Wars had existed in 1962, it would have fit nicely at movie theaters alongside fare like The Longest Day, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and Dr. No.

Star Wars moved beyond the bittersweet nostalgia of American Graffiti by undergirding the picture’s moral outlook with a mythic story structure and classically archetypal characters. This made the story and its message seem timeless, like the expression of some eternal truth. Lucas, in his interview with Farber, described his values as “all that hokey stuff about being a good neighbor, and the American spirit and all that crap. There is something in it.” Star Wars offered affirmation that such old-fashioned ideals still held meaning and relevance.

A pivotal yet sometimes overlooked factor in Lucas’ treatment of this material is that, unlike many of the copycat space operas that followed it—including, ironically, the 1980 remake of Flash Gordon—Star Wars never condescends to its inspirations. The snobby critics who lambasted Star Wars might have gone for the picture if Lucas had treated it as some sort of smirking inside joke. But there is nothing spoofy or tongue-in-cheek about it. It is a straightforward, heartfelt story that could be taken at face value. This appealed to viewers, if not reviewers.

Although its ethics can’t be categorized as entirely conservative (see Chapter 29) or even overtly political, Star Wars struck a chord with the American public by harkening back to the sincere and uncomplicated outlook of a bygone era. Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign struck many of these same notes. Reagan, calling for a return to the kind of fundamental morals and simplistic policies that guided America during what might be thought of as the American Graffiti era, captured the White House. Once in office, his administration mined the Star Wars phenomenon in more overt ways. Reagan, a Cold War hard-liner, referred to the Soviet Union as “the Evil Empire” in a 1983 speech. That same year, Reagan unveiled the Strategic Defense Initiative—a proposed system to protect the United States from nuclear attack by placing interceptor missiles on orbital satellites—which Senator Ted Kennedy labeled “Star Wars.” Although this sobriquet was intended derisively, Reagan’s supporters loved it, and the moniker stuck. Defending his “Star Wars” idea in 1985, Regan quipped, “If you will pardon me stealing a film line, the Force is with us.” An irritated George Lucas attempted to sue two conservative advocacy groups who were promoting SDI using the “Star Wars” nickname. The lawsuit failed. By then, Reagan had been reelected in a historic 1984 landslide, the ballot equivalent of Star Wars’ box office returns.

Conservative politicians including Margaret Thatcher (center) took the public’s embrace of Star Wars as a signal that voters wanted a return to old-fashioned, black-and-white ideas and policies.

All of which disproves the final complaint frequently lodged against Star Wars by its critics during the late 1970s: that the movie is childish and vacuous. In their 1979 book The Movie Brats: How the Film Generation Took over Hollywood, authors Michael Pye and Linda Myles followed a lengthy interview with Lucas with a dismissive appraisal of the director’s most famous work: “Star Wars has been taken with ominous seriousness. It should not be. The single strongest impression it leaves is of another great American tradition that involves lights, bells, obstacles, menace, action, technology and thrills. It is pinball on a cosmic scale.”

Pye, Myles, and many other critics accused Star Wars of being a movie with nothing to say. In actuality, Star Wars simply wasn’t saying what its detractors wanted to hear. It was, however, delivering a message that a growing percentage of the American public wanted to believe.