CATTLE ARE NOT MINDLESS MACHINES that eat and reproduce. How they adapt to handling, feeding, and management practices makes a big difference in how well they do. The more you learn about them and the reasons behind their behavior, the better you can care for them.

Cattle are intelligent and curious, relying not only on instinct but also on figuring things out. They have good memories and a certain amount of adaptability — which makes them very trainable. If you handle them consistently, they learn what to expect from you and what is expected of them.

Instincts and thought processes equip a cow to handle situations like finding the best grass, being alert for predators, defending her calf, or remembering the location of a water source, mountain trail, or hornet’s nest. She may not understand, however, that she must go around a long fence and through a gate to reach hay in the adjacent pasture — until she’s done it once and remembers the gate. Her thoughts are very direct; she can see the hay through the fence, so she wants to go straight to it. But she can learn about gates.

Some cattle are smarter than others. Some are wilder or more nervous; others more mellow and less easily alarmed. Disposition is usually a combination of attitude and intelligence. A nervous or wild individual can be tolerated if she is smart enough to be trainable — to learn that you are not a threat and that if she follows the proper routine she is not going to be hurt.

Cow personality or manageability is a combination of genetics and experiences. How the cow has been handled from calfhood can affect her attitude toward people. A good stockman who handles cattle in a patient, calm manner will have gentler, calmer cattle than the stockman who gets them excited. Cattle never forget a bad experience; if mistreated, they will balk at getting into the same situation again.

1. Understand the survival response. Cattle evolved as prey animals, relying on smell and sight to detect predators and responding to danger by fleeing. They fear any new thing they don’t understand — a deeply ingrained survival response. Their ears are more sensitive (especially to high-pitched noises) than human ears, and their wide-angle vision — eyes set wide apart so each eye sees a different picture and to the rear — enables them to see an approaching predator while grazing.

Cattle are wary of anything new until they see that it’s no threat. They may balk at a shadow, puddle, or anything strange along the trail, by the gate, or on the fence. They may spook at something colorful or an abrupt movement. A strange person standing by the fence or gate, or someone in the field shoveling a ditch, bent over behind the bushes, may cause cattle to balk or spook.

Be aware of things that can scare them, and try to make moving and handling a good experience instead of a bad one. Don’t leave your sweat-shirt on the corral fence or your coffee cup along the chute. Try to see what they are seeing. It may be a reflection off a puddle or windshield, a discarded pop can, a gate chain rattling, a dog at the other side of the corral, people moving up ahead, or the smell of the neighbor’s barbecue on the breeze. Calm cattle look at the things they are afraid of, giving you a clue, whereas wild cattle get excited and try to run back over you to get away.

2. Introduce procedures gradually. The secret to handling cattle is to train them to the way you need to work with them and to all new procedures gradually, in a noncomfrontational manner. Spend time walking quietly among them in their pen or pasture to get them used to you. Introduce new experiences slowly. Walk them through a new facility in a calm manner before they have to undergo any painful procedures. If their first experience in the chute or corral is painful (e.g., branding, dehorning), they may try hard never to go in again. (See chapter 5.)

3. Maximize human-bovine relationships. Human-bovine relationships work well because cattle are social animals and accept a “pecking order” in the herd. They submit to a higher-ranking herd member and can transfer this submission to a human handler. If cattle know and respect you, accepting you as “boss cow,” they will submit more readily to your domination — for example, going through a gate when you insist, rather than running off or knocking you down.

4. Understand pecking order. Pecking order is an important fact of life for herd animals. The bossiest, most aggressive cow is “top cow” — she gets first choice of feed and water. Other herd members fight to determine who is next in the pecking order. Often the most serious fights are among lower-ranking cows trying to move up to a better social position. Top cows rarely have to defend their titles because everyone has learned to respect them. They have mind control over the others. You can use this same control when handling cattle that know and respect you.

Understanding social order helps you manage and feed cattle properly, spreading out feed so lower-ranking cows find space to eat and locating salt and water in accessible spots (not in a fence corner), so dominant cattle can’t hog it and keep timid ones away.

COWS AS PETS

Don’t make the mistake of letting an animal lose respect for you. If you have a favorite cow or raise an orphan that becomes a pet, don’t spoil her. And never make a pet of a young bull. A pet bovine thinks of you as one of the herd, so you must be the dominant one. It’s bovine nature to be bossy and pushy. Don’t let the animal become aggressive, lacking any fear or respect. Stockmen have been killed by pets, especially bulls. If a pet starts shoving or butting with its head, discipline her with a swat or twist an ear. Gain the animal’s trust, but don’t let her lose respect for your dominance.

Cattle’s keen sense of smell tells them much about their surroundings and each other. Smell is more reliable and important to cattle than sight or sound. If a strange odor drifts by on the breeze, cattle are instantly aware of it. Unlike humans, who smell only through the nose, cattle have two areas of odor reception: the nose and the Jacobson’s organ in the roof of the mouth. When smelling, cattle may raise their heads, mouths open, tongues flat and upper lips curled back, inhaling air to sample it with the sensitive roof of the mouth.

When a calf is born and gets up to nurse, he learns the smell of his mother. From then on he knows exactly who she is. A cow knows her calf’s bawl and he knows his mother’s voice, but smell is the most reliable clue for recognition. Even after they’ve located one another by bawling, a calf often takes a quick smell of the cow after running up to her, before he starts nursing — especially if he made a mistake in the past in his overeagerness and was kicked by an indignant herd member. The cow also checks by smell to make sure the calf is her own before letting him nurse.

Cows often leave their young calves to nap when they graze. As calves become older and more independent, cows and calves may get widely separated in large pastures. They often go back to where they last saw each other (the last nursing) as a meeting place. But if the calf has wandered off with other herd members, or the herd has been moved to another pasture, the cow sniffs the fresh trail and follows until she finds them again.

Smell is the most important social sense. Two cows sniff each other before deciding whether to fight. A subordinate cow gingerly smells another cow and then backs off, recognizing a bossier individual.

The bull uses smell to check for cows in heat — whether coming into heat, in strong heat, or going out of heat. Chemical attractants called pheromones signal if the individual is nervous, afraid, relaxed, angry, in heat, and so on. Specific estrous odors are released from the body surface when a cow is in heat.

Smell also helps determine what cattle eat. They are fussy eaters and rely on their noses to tell if feed is good or bad. They don’t like wet hay or grain and often refuse feed that looks perfectly good to humans, just because it smells different.

A cow’s selection of food is partly instinctive and partly learned from experience with various feeds. For instance, a cow that’s never had grain may refuse to eat it. But one that grew up eating grain will eat it readily, even many years later. Calves learn much of their food preference by mimicking other herd members, especially their mothers. A hand-raised calf may not try hay or grain (or water) until several weeks old, not having a role model to copy, unless you stick the feed in his mouth. Orphaned calves often do better if they can live with an older animal to teach them the facts of life about eating. Cattle have other needs associated with grazing:

The need to graze in groups. Yearlings are the most gregarious; where one goes, they all go. In large pastures, cattle often form bonds with other herd members, grazing with a buddy or in family groups.

The need to graze in groups. Yearlings are the most gregarious; where one goes, they all go. In large pastures, cattle often form bonds with other herd members, grazing with a buddy or in family groups.

The need to be in small groups. Cattle are uneasy and restless if separated from the main herd, yet they also need their individual space. If you put too many in a small area, they get restless and do more walking than grazing. They do best in small groups, not confined in small areas within large groups. Ideal pasture rotation and stocking rate will depend on type of grass, climate, terrain, and type of cattle.

The need to be in small groups. Cattle are uneasy and restless if separated from the main herd, yet they also need their individual space. If you put too many in a small area, they get restless and do more walking than grazing. They do best in small groups, not confined in small areas within large groups. Ideal pasture rotation and stocking rate will depend on type of grass, climate, terrain, and type of cattle.

The preference for tender new growth. Cattle prefer tender new regrowth and avoid old, mature plants. Mature, coarse plants are not eaten at all unless there isn’t much feed left in the pasture. Rotational grazing works better for many pastures (allowing more cattle per acre and a healthier situation for plants) than season-long grazing in which preferred plants are continually overused.

The preference for tender new growth. Cattle prefer tender new regrowth and avoid old, mature plants. Mature, coarse plants are not eaten at all unless there isn’t much feed left in the pasture. Rotational grazing works better for many pastures (allowing more cattle per acre and a healthier situation for plants) than season-long grazing in which preferred plants are continually overused.

The need for clean pastures. Cattle won’t graze near manure. In small pastures, fecal deposits may hinder use of some of the grass — nature’s way to limit parasite infestation. Larva that hatch from worm eggs in manure crawl up adjacent plants, ready to be eaten, to reinfest grazing animals. However, cattle will eat grass around the manure of other species such as horses or sheep, whose parasites can’t live in cattle.

The need for clean pastures. Cattle won’t graze near manure. In small pastures, fecal deposits may hinder use of some of the grass — nature’s way to limit parasite infestation. Larva that hatch from worm eggs in manure crawl up adjacent plants, ready to be eaten, to reinfest grazing animals. However, cattle will eat grass around the manure of other species such as horses or sheep, whose parasites can’t live in cattle.

The need for adequate grazing time. Cattle may shortchange themselves on grazing time and lose weight if weather is very hot or cold. In extreme heat, cattle spend more time in the shade and graze at night. In winter, when cattle are cold and days are short, it must be about 20°F (−7°C) or warmer before cattle start grazing in the mornings. They may need hay or supplement to get them going sooner.

The need for adequate grazing time. Cattle may shortchange themselves on grazing time and lose weight if weather is very hot or cold. In extreme heat, cattle spend more time in the shade and graze at night. In winter, when cattle are cold and days are short, it must be about 20°F (−7°C) or warmer before cattle start grazing in the mornings. They may need hay or supplement to get them going sooner.

As days get short and cold, cattle’s use of some pastures may change. This must be considered when managing pasture or assessing amount of feed left in it. Cattle spend less time on shady sides of hills or canyons and stop using them altogether during the shortest or coldest days. Snow is deeper in shaded areas. Even if there is good grass left, cattle may not use it.

The need for hay in cold weather. Cows don’t move around much when it’s cold or windy and don’t like to eat grass with frost on it or push their noses through crusted snow. They won’t eat enough to maintain body condition. But they’ll readily eat an “easy” feed such as hay. Cattle will eat hay or straw even at night in cold temperatures, but they won’t graze under those conditions.

The need for hay in cold weather. Cows don’t move around much when it’s cold or windy and don’t like to eat grass with frost on it or push their noses through crusted snow. They won’t eat enough to maintain body condition. But they’ll readily eat an “easy” feed such as hay. Cattle will eat hay or straw even at night in cold temperatures, but they won’t graze under those conditions.

Stormy weather or heavy rain can reduce grazing time; cattle move to shelter or brush to wait out the storm. But light rain on a summer day encourages grazing; cattle that were lying around will get up and graze if the temperature drops a bit due to light rain. Cattle on green pasture often stop grazing (or eat less) when grass is wet, but cattle on drier grasses increase feed intake when grass is softened up by rain or snow.

Cool, damp weather without wind doesn’t bother them; it reduces their need for water and they may go 24 hours or longer before going to water. They will do more grazing than on a hot day, spreading out and using rough terrain.

COLD-WEATHER BEHAVIOR

Cattle with a good hair coat for insulation manage well in cold climates but still like comfort. Every pasture in windy regions should have some kind of windbreak.

If weather is extremely cold or windy, the cattle huddle in groups, taking advantage of body heat from the herd and sheltering each other from the wind. During a storm, cattle may stand up all night.

They also need good bedding areas. When weather isn’t windy, they’ll lie down in a sheltered place or steal a warm “body spot” from a subordinate cow. On cold nights there’s a lot of jostling for bedding spots if cattle are confined in a small area. But if there is ample space and enough bedding, even the low-ranking cows can find a comfortable place.

Knowing which conditions encourage grazing or hinder it can help you make decisions about pasture rotation, supplementation, stocking rates, or movement to different pastures.

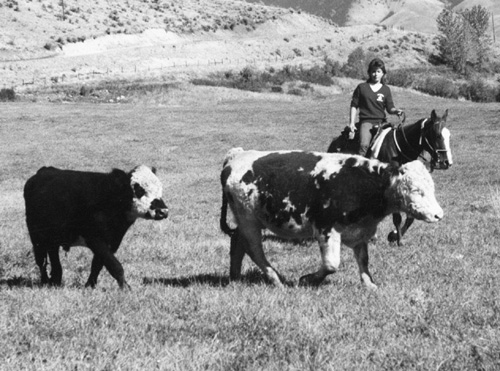

If you know how cattle think and react, you can train them to be manageable. If you will be herding them with horses, get them used to someone riding among them. If they will be handled on foot, walk among them often (especially the young heifers) so they know you, trust you, and respect you. The easiest time to gentle them is at weaning, when they associate you with food. A quick way to gentle weaned calves is to feed them for a few days with a wheelbarrow, taking a bale of good hay among them and scattering it by hand. They soon look forward to seeing you. Their first winter, even if you feed with a pickup, take time to walk past them afterward, talking to them — and you’ll have a herd of gentle heifers instead of flighty wild ones. Also keep in mind the following guidelines:

1. Spend time with them. Talk softly without looking right at them if they’re scared. If you look them in the eye, they think of you as a predator and become more nervous. Pretend to ignore them as you talk or sing softly, putting them at ease. As you discover which ones are wildest or most timid, give them a little more room or move more slowly near them, letting them become accustomed to you.

2. Convey that the herd is the safest place. If you handle them with horses, train them to respect a horse and learn that they cannot outrun one, that it’s futile to try to leave the herd and run off, and that the safest place is in the herd, going in the proper direction. Never let a heifer or young cow run off or hide in the brush when moving cattle. If she gets away with devious behavior, she’ll try it again. If you build a good foundation of respect and educate her while young to learn good habits, she won’t give you as much trouble later.

3. Don’t hurry them. They’ll learn that they are harassed least when staying with the group, behaving themselves. They are herd animals, so it’s easy to train them to stay together. Cattle split and try to run off only if they are frightened, being pushed too hard, or trying to get away from abuse.

When you round up cattle, move them from pasture to pasture, or send them into corrals or through a working pen, move them with the least stress and effort — it will be easier on them and you. Use patience, understanding, and consistency. If you handle them properly, they develop patterns of response that make your job easier.

Stress reduces ability to fight disease, decreases weight gains, inhibits digestion, and increases shrink (temporary weight loss from nervously passing more manure and urine than usual) — an important factor when selling cattle. To avoid bruising, don’t ram cattle through gates or beat on them. Stressful situations make them harder to handle next time, so try to minimize excitement, agitation, and use of electric prods.

Move cattle quietly and sensibly. Too much yelling, chasing, and dogging (sending dogs after them) can get them very excited. They usually don’t fear people, but noise and movement can quickly change that. It takes only a few seconds to upset them but may take 30 minutes to calm them.

Each animal has his own space in which he feels safe. If you come closer than that imaginary boundary, he will move away from you. This “bubble of security,” or flight zone, is much larger for the wilder, suspicious animal than for the trusting individual. Size of flight zone is partly determined by amount and type of contact with people, and inherited temperament (nervous or placid). Excited cattle have a larger flight zone than they have when they are not upset.

LEAVE DOGS AT HOME

Use of dogs can be counterproductive, distracting, or so upsetting to cattle that they are not cooperative. Good dogs are useful when moving cattle in large pastures, but dogs in a corral situation cause more problems than they solve unless the dogs are exceptionally well trained. Most dogs just worry the cattle and put them on the fight. Some cows expend more energy chasing a dog than heading for the corral. And in the corral, a dog may cause a cow to run over you.

With eyes positioned at the sides of the head, a cow sees a different image with each eye — and can move each eye independently to focus on a specific object. Sometimes cows focus both eyes to the front. Cattle have a wide field of vision — about 330 degrees — and can see in every direction except directly behind them.

If you are trying to move cattle without stressing them, pay attention to flight zone and the animal’s signals and intentions. Approach quietly and slowly, giving the animal or herd time to see you and realize you are not a threat. Although cattle have wide-angle vision, they have a blind spot directly behind them and can spook if you come up on them the wrong way; they will be nervous if you go directly behind them where they cannot see you.

Cattle will turn to face you, if you are still outside their security bubble. Their instinct for avoiding danger is to face it and keep a safe distance. You want them to see and recognize you; startled animals take flight, running first and thinking later.

If working cattle in an enclosed space like a corral or alleyway, remember that confined cattle become more nervous and their bubble may be larger; if you get very close they may become agitated, especially if you approach head-on. If you invade a cow’s space when she is cornered, she may panic, try to jump the fence, or run back over you. If cattle in an enclosed space start to turn back, you should back out of the flight zone so they can stay calm. (See chapter 5.)

To move cattle, walk (or ride) on the edge of the flight zone, penetrating it to make them move away from you and getting farther from them to slow or stop them. When they go in the proper direction at the proper speed, ease up as a reward and only press closer again if they stop.

To move a cow forward, approach from behind the shoulder — her point of balance. If you approach ahead of the shoulder, she will turn away or go backward, defeating your purpose. To keep her moving forward, stay to the side at the edge of the flight zone, at a position behind the shoulder. Never follow directly behind; if you approach a cow in her blind spot, she may kick you.

One person can handle gentle cattle, but it helps to have two if you are bringing them very far or into a corral. One person goes alongside the leaders just behind their point of balance, and the other moves along the herd, in a position where the cattle won’t try to go between the front and the rear person. You rarely have to chase cattle; just move up on them to encourage them to go forward in the proper direction. Keep proper distance to get the proper response.

If they start to slow, move closer, putting more pressure on their flight zone so they’ll move again, then veer off at an angle to relieve pressure so they’ll be at ease and not start traveling too fast. Flighty cattle require more playing room than gentle cattle.

With one person ahead of them, calling, and one person behind to herd stragglers, two people can move a lot of cattle easily. Cows follow much more readily and eagerly than they can be driven — with less energy expended by them and by you.

THE BASICS OF MOVING CATTLE

Avoid yelling or running. The cattle will train better.

Avoid yelling or running. The cattle will train better.

Don’t try to move them from the rear; they may run off or stop and turn to look at you.

Don’t try to move them from the rear; they may run off or stop and turn to look at you.

Move them at a slow walk. Concentrate on moving the leaders; where they go, the others follow.

Move them at a slow walk. Concentrate on moving the leaders; where they go, the others follow.

Get the herd moving before steering them in a certain direction.

Get the herd moving before steering them in a certain direction.

Approach at an angle to start them the way you want them to go.

Approach at an angle to start them the way you want them to go.

Once the leaders are moving, move with them, just behind the leaders’ shoulders to keep them moving.

Once the leaders are moving, move with them, just behind the leaders’ shoulders to keep them moving.

The herd will stay together if you work quietly; stragglers usually follow.

The herd will stay together if you work quietly; stragglers usually follow.

Move a group of cattle in the proper direction by putting pressure on the “flight zone” of the leader.

Once the leader is moving, follow just behind the leader’s shoulder to keep the animal moving.

Some bulls don’t herd their cows, but many do, especially if there’s another bull in the next pasture. He herds his cows away from the fence, to a corner away from the other bull. He dominates his cows, even the ones that at first try to run off to defy him. Soon all he has to do is run back and forth snorting, and they respond by grouping and being herded. Cattle are used to a pecking order and submitting to dominant individuals.

Even working cattle on foot, you can accomplish the same thing if cattle have been trained to respect you. Cows won’t be hard to handle if they’re accustomed to you, since they know they cannot succeed in being devious. They could outrun you if they wanted to, but generally don’t try if they respect you as they do the bull when he herds his cows. They accept you as boss, especially if they’ve never been allowed to get away with running off. If a cow decides to run instead of going to the gate, she’ll still respect you if you’ve trained her properly. Usually all you have to do is make a short run to start heading her off, speaking to her firmly, and she’ll change her mind and head for the gate.

This type of respect is gained from handling cattle from the time they are young — being firm and consistent but not abusive — and culling any wild or dangerous individuals that do not learn to respect you.

Most accidents with cattle happen when trying to force one to do something she doesn’t understand (she becomes agitated and panics), or when a cow considers you a threat to her calf. The cow generally won’t attack (especially if she knows and respects you), but she can accidentally hurt you in efforts to get away if you press them too closely.

Always have an escape route in mind — enough room to dodge aside if an animal backs into you or turns around and runs back. Even a gentle cow may kick if you come up behind and startle her, and a nervous or defensive cow will kick if she feels threatened when you get too close. Cows have a greater range of side motion when kicking than a horse does; you are not out of range when standing beside a cow. She can kick you if you are anywhere behind her front shoulder.

When working cattle it helps to know them, to try to predict their actions and be prepared for what they might do. Some become insecure when being worked and are apt to panic or become aggressive. Some are not aggressive but may hurt you if you’re in the way. An old placid cow may shut her eyes to avoid a flailing whip, walking right into you by accident. Two fighting animals may not see you at all and smash you into the fence as one pushes the other. A protective mother with a young calf may become aggressive when upset. In fact, some cows can be more emotional and dangerous than bulls.

If taking cattle a long way, let them drift at their own speed in a long stride rather than in a big, tight bunch. It is their nature to follow a leader single file; this will stress them least and avoid the problem of a big bunch milling around on a trail or roadway with no leaders.

If you’re afraid of them, they’ll quickly take advantage of you. No one who is actually afraid of cattle should ever work them in a corral. There is no need to be afraid of cattle. If you have a dominant attitude, they respect you and won’t charge at you.

You may be able to predict a cow’s actions by reading her body language. Cattle are long-necked and front-heavy, relying on head and neck for balance and directional control of body movement.

If a shoulder drops slightly, she is about to turn to that side.

If a shoulder drops slightly, she is about to turn to that side.

If the skin rolls or twitches in the shoulder, she’s getting prepared to turn quickly to that side and perhaps spin around.

If the skin rolls or twitches in the shoulder, she’s getting prepared to turn quickly to that side and perhaps spin around.

You can tell from eyes and head position if an animal is scared or angry. A steady stare often means aggression; the animal may charge if you give her an excuse. Rapidly moving eyes mean she’s afraid or nervous. Slowly moving eyes mean you’re being evaluated as a potential threat. An animal that slings his head is giving a warning; this is an aggressive action, and if you move he may charge. An animal with head held low is very aggressive and poised to charge, ready to hit you with his head. An animal with head above shoulder level may be nervous or frightened, whereas head held at normal (shoulder) level indicates the animal is unconcerned — not feeling threatened — or still evaluating whether you are a threat. An animal that doesn’t face you, keeping his rear end toward you, is either frightened and wanting to flee or unconcerned and not needing to keep an eye on you.

If an animal makes aggressive gestures, hold your ground and stare him down (unless you are too close to his personal space — in that case, slowly back up). Do not run. Aggressive cattle always charge at movement. Stand still and project your most dominating thoughts; you are the boss! If you must move, move slowly. If you convey your dominance to the animal before he charges, he may not follow through with aggressive action. Have a stick or whip — a weapon of some kind — when working with potentially aggressive animals; this can give you a psychological upper hand. Not only will they hesitate to charge if you have a weapon, but you will feel more confident — they can sense it and are less apt to charge at you.

If an animal does charge, yell. A high-pitched scream will often deflect or interrupt the charge because cattle have sensitive ears. A scream may distract the animal so you can dodge and get to the fence. Cattle move away from high-pitched noises.

The best way to avoid being hurt is to handle cattle properly (less chance of getting them frightened, upset, or on the fight), handle them enough to train them (so they know you and know what to expect from you, and accept you as “boss”), and select for good disposition and calmness when building your herd. Any unmanageable or truly mean animals should be culled.