NUTRITIONAL NEEDS VARY according to breed and age, whether or not a cow is lactating, whether the weather is warm or cold. Cattle can do well on many types of feeds as long as the feed contains sufficient nutrition and is provided in adequate amounts.

When raising beef cattle, you turn forage into meat. Pasture grass, a bale of hay, a scoop of grain — all become energy for body maintenance and warmth on a cold day. These foods are building blocks for growth as the animal matures, reproduces, and puts on weight. Five main types of nutrients are needed for life and growth: energy, protein, vitamins, salt and other minerals, and, of course, water.

Energy. The main group of energy nutrients is carbohydrates. Sugars and starches are simple carbohydrates — found in grain feeds such as corn, oats, and barley — that are easy to digest. These feeds have high energy value for their weight and volume. Cellulose, one of the main types of fiber in plants, is a complex carbohydrate. Hay and grass contain a lot of cellulose. Because it is more difficult to digest than starches or sugar, cellulose has lower energy value; but since ruminants can digest large amounts of cellulose in the rumen, it can provide adequate energy for beef animals.

Fats are another type of energy nutrient, but the energy in fats is much more concentrated than that in carbohydrates. Fats are not easily digested by the ruminant and should never make up more than 5 percent of the ration. A natural diet of forages contains very little fat.

Energy is the most important part of the diet. Protein, vitamins, and minerals are wasted unless energy requirements are met first. Forage (especially pasture, which the animal harvests himself by grazing) is always the most economical source of energy.

Energy is usually expressed as percentage of total digestible nutrients (TDN) in the ration. TDN content in grains is more concentrated and higher than TDN in fibrous forage (pasture and hay).

Proteins supply building material for muscles, bones, blood, organs, skin, hair, hoof and horn growth, and production of milk. During digestion the proteins are broken down into amino acids (the nitrogen-containing subunits of protein), which are absorbed into the bloodstream and carried to all parts of the body, where they are recombined to form body tissues. If an animal is fed more protein than needed for growth, tissue repairs, or milk production, the nitrogen is used as an energy source and the balance is discarded in urine. Since feeds high in protein (alfalfa hay or supplements) cost more than other feeds, feeding an animal more protein than it needs is a waste.

Protein for young animals, lactating cows, or cows in late pregnancy can be supplied by good legume hay such as alfalfa or clover, green pasture grasses, or high-quality grass hay. Protein supplements include cottonseed meal, soybean meal, and linseed meal. A beef animal doesn’t need protein supplements as long as he has good hay or pasture.

Vitamins are needed in small amounts and are necessary for health and growth. Green pasture, alfalfa hay, and good grass hay are sources of carotene, which the animal converts into vitamin A (stored in the liver). Other needed vitamins are provided in feed or created through digestion, except for vitamin D, which is necessary for bone growth and mineral balances. Vitamin D is formed by the action of sunlight on the skin. No animal will be short on vitamin D unless he spends all his time indoors in a barn or shed.

Vitamin E is important for muscle development; a deficiency (along with selenium deficiency) can lead to white muscle disease in young calves. Vitamin E is found in natural feeds. Vitamin K is important for blood clotting; it, too, is found in feeds or created in the rumen. B vitamins are important for energy metabolism and the health of red blood cells. Vitamin C is an antioxidant that protects cell membranes. Because microbes in the rumen synthesize water-soluble vitamins (C and B vitamins), the beef animal will never be lacking unless there is a health problem, such as disrupted rumen digestion.

Minerals are needed in very small amounts but are essential to life processes. Sodium, chlorine, and potassium are crucial to fluid balance in body and bloodstream. Iron is an important part of red blood cells; without it the blood could not carry oxygen. Bone formation and milk production depend on calcium and phosphorus. Because they occur naturally in forage and grain, minerals are usually supplied in feed. However, minerals need to be supplemented in certain circumstances. Some regions where feed is grown are short on copper or selenium, for instance, making the pasture grazed, and the hay or grain harvested in those areas, also short on these minerals.

Salt contains two important minerals, sodium and chlorine — the only minerals not found in grass or hay. Always provide salt, in block form or loose. Salt is the only mineral cows have the nutritional wisdom to eat at a level to meet their needs. Care must be taken in providing other minerals; if cattle don’t need them you are wasting money, and overdose of certain minerals can be harmful. A mineral supplement mixed with loose salt can be used if feeds are deficient in certain minerals. Trace minerals (needed only in tiny amounts) include copper, iron, iodine, cobalt, manganese, selenium, and zinc.

Phosphorus supplementation is most important when cattle graze year-round. Phosphorus deficiencies are most likely to develop in cows kept for long periods on dry grass or crop residues. Phosphorus level in most harvested forages (hay) is adequate, especially for dry cows, unless it’s very poor quality hay. The time to supplement is when they are kept on dry grass a long time or milking heavily.

Whether or not certain minerals need to be added to cattle diets depends in part on feed quality (maturity of hay at harvest and the condition of the hay at harvest, such as whether it was rained on before baling), types of feed, and storage time (whether hay is fresh or old). One of the most important factors, however, is the mineral content of the soil in which it grew. Providing adequate minerals for livestock is essential to their health, disease resistance, fertility, growth, and weight gain, among other things.

A mineral supplementation program must be designed with all of the above factors in mind and may need to be altered during the year as livestock needs change or feed sources and quality vary. Sometimes no supplements are needed, but in other situations a supplement is crucial to a herd, and without it, the stockman is courting disaster. Adequate levels of copper, zinc, manganese, and selenium, for example, are crucial for a healthy immune system and for optimum reproduction. The most important time to supplement trace minerals is during the last 60 days of pregnancy, when the fetus’ immune system is developing, and during the 60 to 90 days after calving until the cow is rebred.

Cows don’t have the nutritional wisdom to balance their diet to meet mineral requirements; the belief that cows eat minerals because they need them is false. They eat them because they want the salt mixed with them, or because they taste good because of a flavoring agent.

Consult with your vet or a livestock nutritionist to design a mineral supplementation program that will work for your herd. The proper amounts of needed minerals can be added to loose salt or given via injection (such as Multimin, which contains copper, zinc, manganese, and selenium). A good injectable product is often the best way to make sure each animal gets the proper dose, since some individuals won’t eat the salt/mineral supplement and others may consume too much.

The cost of a proper mineral supplement program is small compared to the cost of trying to resolve a “wreck” due to mineral deficiency. Serious problems, such as disease, low conception rates, calving difficulties, and poor weight gains, can all be caused by an inadequate or improper mineral program.

Cattle, sheep, and goats are ruminants: cud-chewing animals with a stomach that has four compartments. Cattle burp up hurriedly eaten feed and rechew it more thoroughly later. Plant-eating animals must have a way to break down cellulose and other fibrous material. Ruminants have the most efficient digestion system for handling plant material.

The ruminant stomach has four compartments: rumen (paunch), reticulum (honeycomb), omasum (also called “manyplies” because of its numerous folds or plies, which are like pages of a book), and abomasum, or true stomach, which is similar to the human stomach. Rumen and reticulum work together as a fermentation vat; abomasum works as true stomach, secreting the same enzymes and acids found in animals with a simple stomach.

Cattle and other ruminants have four-part stomachs:

1. Rumen, a large storage area for feed where bacteria help break down roughage

2. Reticulum (honeycomb), where walls catch foreign material that could injure the digestive system (also called the “hardware stomach”)

3. Omasum, where liquid is removed from the food

4. Abomasum (true stomach), where digestive juices are secreted to finish breaking down the feed

Cattle have no top incisors (front teeth) — just a hard dental pad at the front of the top jaw. Grass and other forage is cut off with the lower teeth biting against the dental pad or with tongue wrapping around the grass and a swing of the head breaking off the mouthful of feed. The strong tongue pulls feed into the mouth.

A cow chews food only enough to moisten it for swallowing, eating a lot in a hurry. After being swallowed, food goes into the rumen. When the animal has eaten his fill, he finds a quiet place to chew the cud. He burps up a mass of food along with some liquid (which helps it come back up), swallows the liquid, then chews the mass more thoroughly before swallowing it again and burping up more. Rechewed food goes into the omasum (third stomach), where liquid is squeezed out, and then goes into the abomasum (fourth stomach).

If you teach an orphan calf to drink milk from a bucket, much of the milk’s nutritional value is lost because the milk goes into the rumen. If he is fed with a nursing bottle or nipple bucket, however, the calf’s sucking reflex creates a direct pipeline into the true stomach where nutrients can be absorbed.

When a calf is born, his rumen is not developed enough to digest fibrous food; the calf functions as a monogastric (single stomach) animal, digesting milk. The rumen begins to develop only after he begins to eat solid, fibrous food. Most beef calves start eating forage in the first week of life and are chewing the cud by 2 weeks of age. To start functioning as a ruminant, the calf also must come in contact with microorganisms and get his own microbes started in the rumen.

Even after they start digesting hay and grass in the rumen, calves continue to digest milk in the true stomach (abomasum). Digestion of milk in the true stomach instead of the rumen is so important to the health and growth of the calf that nature makes sure milk goes into the true stomach even after the rumen is fully developed. When the calf nurses, a signal from the brain causes a fold in the front part of the reticulum to roll over and form a tube that becomes a temporary extension of the esophagus. The milk flows down this “esophageal groove” into the abomasum, bypassing the rumen completely.

In the healthy rumen, microbes thrive in a fluid environment, breaking down, digesting, and creating by-products from feed. For any given kind of feed, a particular pattern of microbes will arise, since some digest fiber and some digest starches. When grain is added to the diet, acidity increases; this limits the bacteria and protozoa that digest cellulose — they need a neutral pH and cannot tolerate an acid environment.

When the animal is fed grain regularly, cellulose-digesting microbes are replaced with starch-users that thrive in the acid environment. To have efficient digestion, the ruminant must have a healthy population of the right kind of microbes to use the type of feed eaten. Any changes should be made gradually. If cattle are fed both fiber and starch intermittently, the microbe population is in constant turmoil; there won’t be the proper amount of either kind of microbe, resulting in inefficient utilization of both types of feed. The rumen needs enough of the starch-digesting microbes to process the grain, or you are wasting your time and money feeding grain.

CORRECTING ENERGY DEFICIENCIES

Cows need energy to do well and have high conception rates, but too often this is interpreted as needing to feed grain, which is inefficient and expensive. To correct an energy deficiency on poor forages, do not feed more energy as concentrates, but make sure protein supply is adequate. A cow can produce all the energy she needs from very poor forages, but she must have enough protein — to feed the rumen microbes — to do it.

The best way to use poor forage (poor pasture, low-quality hay, or even straw) is to add a little protein such as alfalfa hay or a protein supplement. This allows the microbe population in the rumen to increase and thrive, enabling the cow to digest more fiber. She can thus eat more total roughage and turn it into energy more efficiently.

Rumen microbes need adequate protein to function properly. If cattle eat low-quality (dried out, overly mature) grasses or other forages very low in protein, they don’t get enough protein to meet the needs of rumen microbes and their population declines. Then the cow’s ability to digest low-quality forages decreases. If her source of energy is forage, and there’s a reduced population of fiber-digesting bacteria, she can’t eat as much (and loses weight) since it piles up in the rumen and is not swiftly or adequately processed.

Forage (pasture, silage, hay) is the most natural feed for cattle. Ruminants do very well on forage but don’t grow quite as fast or get fat as quickly as when they are fed grain. Many young cattle are finished in feedlots on grain to save time and total feed. If grain-feeding can take an animal to slaughter readiness before going through another winter (on hay), it can be cheaper. But pasture is the most abundant and cheapest feed for other cattle.

Green pasture supplies cattle with all the necessary nutrition and energy; by grazing lush grassland, they take in adequate protein, energy, vitamins, and minerals (unless soils are very low in certain important trace minerals; see page 88). An exception might be early spring grass just starting to grow — making fast growth in which plants have high water content and lower percentage of actual nutrients by weight and volume. Quality of pasture depends on a number of factors, including:

Type of plants grown

Type of plants grown

Level of maturity of plants at harvest

Level of maturity of plants at harvest

Adequate moisture during growth

Adequate moisture during growth

Soil fertility

Soil fertility

If properly grown, cut at the right time (while plants still have high nutrient content, before mature and dry), properly cured, and carefully stored to prevent weather damage, hay can be excellent feed for cattle, supplying all necessary nutrients. Legume hay has more protein than grass hay, and some grasses have more protein than others. Good grass hay cut while green and growing can have a higher protein content than legume hay cut late. For optimal quality, hay should be cut before it is fully mature (before legume bloom stage and before heading out of grass seeds). If you cut hay when about 15 percent of the plants have bloomed, you get better volume and still have good quality. Good hay is green and leafy with small, fine stems.

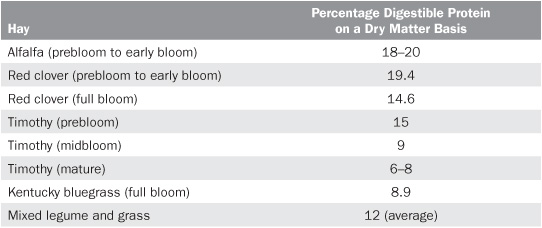

DIGESTIBLE PROTEIN

Native grass hay has energy values comparable to legumes if harvested at the same stage of maturity, but about half the protein. Legumes such as alfalfa may have 50 to 60 percent total digestible nutrients (TDN), whereas mature grass hays have 45 to 50 percent TDN. Grass hay can be lower in phosphorus and is always lower in calcium than alfalfa. But a combination hay made up of alfalfa and grass is better for beef cows than straight alfalfa hay.

Amount of hay needed for an animal varies depending on age and size, body condition, and so forth. Evaluate the condition of the animals and decide whether they are wasting hay or cleaning it up. If hay is unpalatable (e.g., coarse or moldy) or wet, some waste will occur even if cattle aren’t getting enough to meet their needs.

For maximum hay production, plants need adequate nutrients — which may mean using fertilizer, commercial or natural. Cattle manure makes the best fertilizer; clean out corrals once a year and spread the manure over fields and pastures. Hay should be harvested when plants are high in nutrition content, just before they mature and produce seedheads. Total harvest yield may be a little higher after it is fully mature, but protein and digestibility will be lower.

Hay must be properly dried before it is baled and stored; if baled too green it will mold and may ferment, heat, and start a fire. Hay baled too dry will lose nutrients and leaves. Plants contain about 60 percent moisture or more when cut and must be dried to 12 to 16 percent for safe baling and storage. (The actual drying percentage varies with haying and storage conditions.)

Haystack cover: A row of bales down the center of the stack gives a slope to the tarp, so moisture will run off.

Alfalfa (green or fed as hay) is good feed for calves or young cattle, lactating cows, and pregnant cows in late gestation. But they don’t need straight alfalfa because they don’t need that much protein, and rich alfalfa with no grass or other forage to dilute it can cause digestive problems, diarrhea, and bloat. A mix of grass and alfalfa is usually safer and healthier than straight alfalfa. On alfalfa pastures, feed a bloat preventive to keep from losing cattle.

Don’t feed dairy-quality alfalfa hay to beef cattle. It’s much richer than they need, and the risk for bloat is great. It’s also the most expensive alfalfa. For beef animals, feed first-cutting alfalfa if it’s the only roughage source, since it contains some grass and can be an ideal ration. Second- or third-cutting is just alfalfa; it grows back faster than grass. It has more protein than needed and should not be fed by itself. It is an ideal supplement, however, for poor-quality forages such as dry pastures, poor hay, or even straw. Cattle can do well on a mix of straw and alfalfa.

To avoid bloat, feed alfalfa with a high-fiber feed, don’t let alfalfa leaves build up in a feed bunk, allow plenty of space for all animals to eat at once (so some won’t overeat), and never let hungry animals eat leafy alfalfa or they’ll load up the rumen too quickly. Be cautious using wet alfalfa pastures or feeding wet alfalfa hay. Lush alfalfa (especially if just a few inches tall and very palatable and tender) can quickly cause bloat, especially in early morning if there’s dew or frost is on the plants.

Make sure alfalfa hay is not moldy or dusty. Some molds can cause respiratory problems or abortion in pregnant cows. Avoid stemmy, coarse alfalfa. Protein and nutrition is mainly in the leaves, so stemmy hay is less nutritious and low in protein. Cattle won’t eat it well; coarse stems are hard to chew.

SILAGE AND HAYLAGE

Corn silage (made from the entire corn plant) and haylage (legume or legume/grass hay made into silage when cut green) make good feeds. Silage has a high moisture content; 3 pounds (1.3 kg) of corn silage or 2 pounds (0.9 kg) of haylage contain as much dry matter and nutrients as a pound of good hay. Silage and haylage are stored wet and green, and nutrient qualities are preserved by fermentation.

There are two kinds of feed — forages, high in fiber (more than 18 percent) and low in TDN; and concentrates, low in fiber and high in TDN. Concentrates are dense, with more energy — more TDN — for their volume. They are also more expensive than forages but have a higher percentage of easily digested carbohydrates.

CHECKING BALED HAY

Open a bale to examine maturity, texture, color, and leafiness. Also check for weeds, mold, and nonedible foreign matter such as baling twines or wire. Alfalfa hay loses its food value much more rapidly than grass hay when overly mature because most of the nutrients are in the leaves and not the stems. Mature plants have longer, coarser, and more fibrous stems; they may have already bloomed or gone to seed. Stem size and pliability (texture) greatly affect palatability and digestibility.

Check proportion of leaves to stems; leaves are always higher in nutrients. If alfalfa leaves have shattered (too dry when baled) or are not attached to stems, there will be a lot of waste when fed. The leaves will fall to the ground or be lost in the snow where cattle cannot lick them up.

Bright green indicates good harvest conditions and adequate vitamin E and carotene content. If hay gets too dry it loses most of its vitamin E. Hay can be analyzed chemically to determine nutrient value (crude protein and minerals). Borrow a drill from your county agent to sample a bale. The forage sampler tool fits a half-inch drill or hand brace and is drilled into the end of the bale. The sample can be sent to a laboratory for testing. You might need a chemical analysis if you know that a particular deficiency exists in your herd and are trying to provide feeds to correct it, or if you want to test weather-damaged hay or identify excessive nitrates (which can cause poisoning). Check trace mineral levels in hay, as well as the amounts of other elements such as iron, sulfur, and molybdenum that can tie up the trace minerals in such a way that the body cannot use them.

Concentrates include corn, oats, barley, grain sorghum (milo), and wheat; dried distillers grains and corn gluten; wheat bran and beet-pulp (by-products of food processing); protein supplements such as oilseed meals; and liquid supplements (these usually contain molasses and urea, a synthetic protein, along with minerals and vitamins).

When feeding concentrates, remember that not all grains weigh the same. Feeding by quarts or gallons can get you in trouble. Weigh feeds, find out how much your scoop or bucket really holds in terms of weight for a particular feed, and recheck it when changing feeds. Making a change in a steer’s ration without adjusting for weight, for instance, may lead to digestive problems.

If pastures are dry and hay quality is poor, cattle may not get necessary nutrition unless you add supplements. Many cow herds must be supplemented through winter. In northern areas, this means full feed if grass is frozen, snowed under, or dried up; in southern climates it may just mean a supplement for what is missing in forage. In the Southwest, supplements may be necessary when hot or dry weather causes grass to become dormant and lose nutrition.

Supplements are sometimes needed not just because forage has become low in nutrients, but also because cows are eating less. As fiber levels increase with deteriorating forage quality, more of the woody part of the plant is left. As this type of fiber builds up in the rumen and slows down passage of feed through the animal, less space is left in the digestive tract. The animal cannot eat as much feed per day. So cattle are eating feed of low nutritional value and less of it. They lose weight unless supplemented.

Cows without enough energy milk poorly and don’t breed back. But a high-energy, grain-based supplement is inefficient, expensive, and detrimental to cows on poor pastures. Do not feed highly palatable grains and concentrates — cows will just hang around feeding areas waiting to be fed, spending less time grazing and increasing the amount of supplement needed. Because grain supplements are more palatable than dried-up grass, cattle want the supplement instead and eat less grass.

Grain supplements change the rumen microbe population, reducing the ability to digest fiber. If you supplement pasture with grain, cows eat less grass (wanting grain instead). Protein supplements more effectively augment poor-quality grass pasture.

With a protein supplement, cows will eat as much as 50 percent more low-quality forage or even 70 percent more poor-quality hay, but they must have adequate forage to supply the carbohydrates for energy. If you are wintering dry pregnant cows, this increase in feed consumption can enable them to maintain body weight. Always use natural protein (such as alfalfa or other high-protein plant matter) to supplement low-quality forages. Nonproteinnitrogen sources such as urea are not utilized as effectively by cows eating low-quality forages.

If you have a lot of protein-deficient pasture, choose supplements high in rumen-degradable protein like soybean meal, cottonseed meal, or distillers grains. But if cows need more energy, use supplements composed of bran feeds that increase energy without limiting forage use. If short on grass, use traditional supplements based on cereal grains, which decrease the cow’s forage intake without reducing total energy.

Alfalfa hay is an economical protein supplement for cows in late pregnancy or after calving. Beef animals fed a pound of alfalfa hay per 100 pounds (45 kg) of body weight are getting most minerals and vitamins needed, if the alfalfa is grown on good soil. Alfalfa has a high level of calcium, important for young cattle and lactating cows. It’s a good source of carotene (which cattle convert to vitamin A), vitamin E, and selenium, unless the alfalfa was grown on selenium-deficient soils.

PROTEIN ANALYSIS

Protein levels in feeds are measured by amount of crude protein, as determined by a laboratory analysis measuring amount of nitrogen. This is different from digestible protein. A beef cow needs feeds with crude protein content of 9–10 percent. Green, growing grass may have crude protein content of 10–20 percent, but when grass dries out it may drop below 8 percent. The difference between 6 and 10 percent crude protein is vast. Below about 4 percent crude protein, nothing is digestible. The 4 percent that shows up as protein in the laboratory analysis is just the nitrogen combined with the woody portion of the plant. So grass with just 6 percent crude protein has only about 2 percent digestible protein. A grass with 10 percent crude protein has about three times more digestible protein.

PRECAUTIONS WHEN FEEDING GRAIN SUPPLEMENTS

When feeding high-energy grain supplements, there is risk of acidosis if cattle overeat. Acidosis occurs when an acid environment is created in the rumen. Spread the supplement among the cattle so each one gets an equal share.

Overeating this type of supplement may cause liver abscesses, caused by mild cases of acidosis. A liver abscess may not be a problem in a steer being fattened, since he’ll be butchered before the problem becomes life-threatening, but it can be a serious situation in a herd of cows.

If feeding a grain or energy supplement on fall or winter pastures, the best time of day to do so is sundown. The worst time is early morning when cattle are hungriest; they prefer to eat the supplement and are slow to start grazing. Winter days are short, and you want the cattle to graze as much as possible. The purpose of a supplement is to maximize the forage available, but if you feed in the morning, the cattle come to expect the handout, go to the feeding area first thing in the morning, and may stay until noon, not grazing until afternoon.

Giving energy supplements after cattle have done their grazing for the day not only maximizes grazing but also reduces the risk of acidosis since they aren’t so hungry (less apt to overeat on the supplement) and the rumen is less likely to make a pH change, because it is already full. The feed already in it dilutes the grain.

In severely cold weather cattle don’t start grazing until the warmest part of the day. To get them stimulated to graze sooner, “jump-start” them with a little hay.

Protein blocks, or lick tubs if used properly, can be self-feeding. The best type of block is one that limits overconsumption with special binders or unpalatable ingredients along with a degree of hardness so cattle cannot eat the block rapidly but must lick it instead. Salt is sometimes used to limit consumption, but many animals eat too much of the block and drink more water to balance the excess and flush it out of the body. Blocks with large amounts of grain or grain by-products are too palatable and cause cattle to overeat. With the proper types of block or a lick tub, you can put out a two-week supply near water, where cattle will lick for a while when they come to drink and then go back to grazing.

If you don’t have good pasture, sort your herd into groups for different feeding, because their needs are not the same.

Growing heifers. Replacement heifers must gain at least 1.5 pounds per day to be large enough to breed as yearlings. If heifers grow too slowly, they won’t mature soon enough to breed on schedule. Good crossbred heifers grow enough on high-quality roughages alone (good grass hay and alfalfa hay mixed), but straightbred heifers don’t have the hybrid vigor and feed efficiency. Some of them may only gain adequately if feed is supplemented.

Lactating cows during breeding season. These cows need the most nutrients. Cows eat nearly 50 percent more hay when nursing calves and preparing to cycle and breed as they do in late pregnancy. On full feed a 1,200-pound (544 kg) cow will eat 25–28 pounds (11.3–12.7 kg) of hay per day before calving, and about 38 pounds (17.2 kg) per day after calving. The two most critical periods in the cow’s year are the 50 to 60 days just before calving and the 80 to 100 days after calving. Shortchanging a cow on feed quantity or quality at this time may reduce calf vigor and growth, milking ability, and increase risk of scours and length of time before she cycles. Shortchanging her in the 3 months after calving may prevent her from breeding back. If cows calve when they can be on green pasture afterward, feeding takes care of itself. But if cows calve at a time that requires nonpasture feeding during lactation and breeding, be prepared to provide nutritious hay.

Calves on pasture (creep-feeding). You can provide feed for calves in a “creep” — an enclosed area where calves can get in to eat but cows cannot. In some situations, this method is advantageous, such as with fall-born calves when pastures are poor for lactating cows, or when cows must be fed hay. Creep-feeding can also be beneficial during drought when green feed is short, or for first-calf heifers’ calves or very old cows if they’re not milking as well as the rest of the herd. The extra feed might even be profitable with large-framed cattle or calves with great genetic growth potential, enabling them to be a lot larger at market.

But in many instances, creep-feeding does not pay or is detrimental. Sometimes it costs more for feed than the extra pounds are worth at the market. If your cows milk well, pastures are good, and grain prices (and cattle prices) are typical, you don’t need the added expense and labor of creep-feeding. And replacement heifers should never be creep-fed: extra fat in the udder takes up space that would otherwise be used by developing mammary tissue, severely reducing their milking ability.

Calves at weaning. The best situation is to wean calves on green pasture. If you are weaning in a corral and feeding hay and grain, be aware of how the calf’s rumen functions. Even though he’s been eating roughages and now has a functional rumen, stress can interfere with proper digestion because rumen microbes die and the calf cannot digest roughages well. Without enough microbes to break down fiber, the hay he eats just stays in the rumen.

WINTER FEEDING

A cow needs extra roughage to keep warm in winter or body fat is depleted to create energy to keep warm. Extra roughage (more grass hay, or even straw) keeps her warm; digestion and breakdown of cellulose create heat energy. Good alfalfa supplies protein, but grass hay provides more heat energy. If a cow is cold she will do better if given all the roughage she can eat (and a little alfalfa or protein supplement to enable her to efficiently digest it) than if fed straight alfalfa hay. The colder it is, the more grass hay or straw she will eat.

If a cow has winter hair she will do fine on a maintenance ration unless the temperature drops below 20°F (−7°C). When temperatures go below this point (and remember to figure in wind-chill factor) she needs more energy to keep warm. During cold weather, increase the feed 1 percent for each degree of temperature drop below 20°F (−7°C). If temperature drops to zero, her requirements increase about 20 percent — 1 percent for each degree of coldness below her critical temperature (temperature at which she feels cold and needs more heat energy).

A wet storm can also increase nutrient requirements even if it’s not severely cold. A cow’s critical temperature is higher when she’s wet and loses insulation value of her hair. A cow suffers more cold stress in wet weather than in dry cold. Cows that have lost weight or are losing weight are very susceptible to cold stress, so keep track of body condition as you winter your cattle and during the changeable, stormy weather of spring.

If the newly weaned calf is in a corral, make sure his feed is palatable and easy to digest. For this reason, some farmers start calves on grain immediately at weaning. Even though calves must learn to eat it (unless they have been creep-fed) and may not eat much at first, the grain can be quickly digested because it passes through to the true stomach, where it is more fully digested than in the rumen. Remember that it takes a calf 2½ to 3 weeks to adapt to a grain ration.

But after the calf is over the stress of weaning and his rumen starts functioning normally again, remember that a high grain ration can cause acidosis. Always include some roughage during the weaning process — preferably fine and leafy palatable hay. Problems can be avoided by weaning on green pasture. If you don’t have that option, try to reduce stress and provide feeds the calf is most likely to eat. Wean on fine, immature grass hay rather than straight alfalfa.

WIND-CHILL INDEX FOR CATTLE

To convert Fahrenheit values to Celsius use this formula: