1

MY FATHER RETURNS

My father says I should write down all about what happened to me last summer when I got planted in that little French mountain town which was probably one of the awfulest sells in the world because nobody there ever had learned a proper language to speak—I mean, a language like the kind of language you and I and sensible folks speak. These Frenchmen in this little French town didn’t know any better than to speak something they called French.

It all started early last summer just after the war in Europe ended. My father had been away for three years. My mother tried to manage the ranch while my father was away fighting. It wasn’t very easy for my mother to do that. You see, my mother is French; she was born in France. She came over here to school where my father met her. She never had much experience with ranches or cattle or horses until my father took her out here to Wyoming.

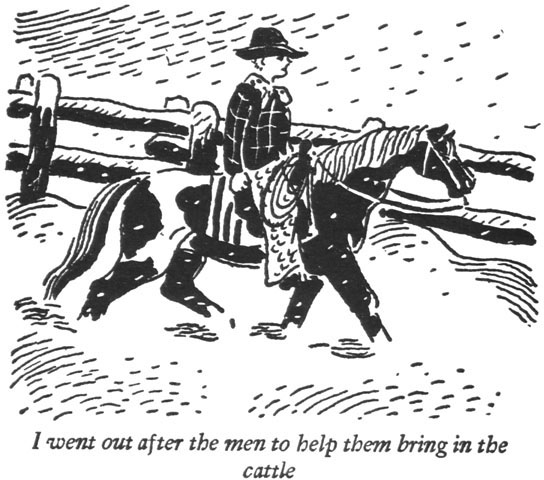

All the same, while my father was away in Europe my mother did what she could to keep the ranch going. We had old Jake Tolliver to help. He is our foreman. He’d been on the ranch when my grandfather was alive. Without Jake, I suspect, we’d never been able to keep the ranch. A year and a half ago I was twelve. That winter we had a lot of snow. Except for Jake and a couple of the older men there was hardly anyone left on the ranch. I knew my mother was worried. So one Saturday, right after the big snow, I figured I was old enough to start earning my keep, especially while my father was away. I saddled up my pony. I went out after the men to help them bring in the cattle from the east range, where the drifts were high.

I don’t know exactly what happened. Maybe it was colder than I thought. Later, old Jake told me they’d had men out looking for me before my pony came in. Luckily, it had stopped snowing. They traced back on the pony’s tracks and got me into the house before midnight. By and by when I woke up I found I wasn’t frozen to death after all but something was wrong with my left leg. I must have fallen off the pony when I got cold and sleepy and didn’t know what I was doing; and I evidently hit a fence post or something sticking up through the snow.

Well, they had the doctor drive out from Piedmont. He set my leg. A month later he came back. He had to set my leg again, because something still was wrong. My mother kept me home from school.

Then, in the spring, my mother took me down to Salt Lake City where they have important doctors. Here, they made more X-rays of my leg. I was worried because I didn’t know then whether I’d ever be able to run or play football or ride a bicycle like the one my friend Bob Collins had bought. Bob’d bought a wonderful second-hand bicycle and painted it red. Probably it was about the fastest thing in the whole country. Ponies are common as dirt in the part of Wyoming where I live, but you don’t come often across red bicycles with a high gear and a low gear like the one Bob Collins owned. It had seemed to me it was the most gaudy bicycle in the world and I pestered my mother to get me one like it.

She explained that right now things were hard on the ranch. That was why, to be honest, I’d wanted to help, thinking maybe if they had another man working on the ranch, such as me, why, things would get enough better for me to have a bicycle like the one Bob Collins owned, with a high gear and a low gear. The low gear was for climbing montagnes—as the French call mountains—and the high gear was for racing.

On the way back home from Salt Lake City I asked my mother how soon I could begin to walk around like anyone else did without having all the hurt and pains in my hip and if she thought maybe by this summer I could ride a bicycle.

I said, “How much longer have I got to use crutches? I can’t do anything with crutches. I don’t like crutches.”

Mother said, “I don’t know if you can ride a bike this summer. Dr. Watkins gave me the name of a man in Chicago and another man in New York. Both of them are supposed to be very wonderful. You don’t exactly have to have an operation. They have to twist the bone just right and I’m afraid it will be rather painful and after that you have to be very brave and make yourself walk without crutches, even if it does hurt—” And then she sort of stopped and looked quick out of the window and I heard her say, as if mostly she was talking to herself, “Oh, Johnny, if your father were only here.”

Old Jake Tolliver, the foreman, met us at the train with the ranch truck. He carried me down, crutches and all, like I was a baby. He must have noticed something in my mother’s face because he didn’t ask her any questions at all on the way home.

For the next couple of weeks it was pretty bad. Most of the time I stayed in my room, going over my coin collection or reading—or not doing anything at all. I told my mother I wasn’t going to see any bone-twisting doctors. I’m afraid I didn’t give her much peace. The fact is, if you want to know, I was plain scared. My mother was gentle, and no one could have been any kinder than she was. Because my father was in the service, mother learned she had the right to take me to an army hospital. Mr. Collins—who was Bob’s father, and an old friend of my father, and sort of looked out for us while my father was away—well, he said that it would save expense if we could find someone just as good as the men the Salt Lake City doctor had recommended. Mr. Collins got busy. He wrote letters. He sent telegrams. He found the Chicago man was almost the best bone specialist in the country. But the man wasn’t in Chicago any more; he was a major, and in the medical corps; he was located at the Letterman Hospital in San Francisco. The very best bone specialist in the country was off somewhere else, over in Europe with the army, so even if we’d have wanted to go to him in New York we couldn’t.

It was all fixed, then, for my mother to take me to San Francisco. Meanwhile, they’d been cabling to my father in France. They’d cabled him about me, so he wouldn’t be concerned when he learned we’d left the ranch—and they cabled him about an idea Mr. Collins had which was to combine the ranches and form a business, with a place for my father as one of the heads of the outfit just as soon as he was released from the army.

But we didn’t get any news back from my father.…

Mother cabled again. So did Mr. Collins. They waited a week—and no reply came. They couldn’t understand that. Mother delayed our trip. They got worried. They knew the war in Europe was ended but they had read in the newspapers how the Germans were still causing trouble with what is called gorilla fighting. Mother, I suspect, was afraid something might have happened to father.

Time stretched out three days—four days—a week. Mr. Collins again drove over. He said maybe he ought to take it up with the War Department; he couldn’t understand it. While he was talking, with mother just sitting there, her face awful pale, we heard thunder from up in the sky.

I can tell you, we don’t have much thunder in Wyoming. When we do have it, we don’t have it usually in late spring. That thunder rose up big and huge—and then we knew it wasn’t thunder. It was a low flying airplane. Mr. Collins said maybe one of the big transports had lost its way and he ran out of the house and mother went to the window and I grabbed on to my crutches and limped for the door.

With a kind of whish and roar to it the thunder went right over our house. Next minute somebody was shooting off revolvers outside. My mother rushed out of the house. Old Jake was yelling. I got as far as the door and accidentally slipped on the rug, the crutches plopping out from under me on each side. I crawled over to get one of the crutches. Then I was crawling over to the other side of the room to get the other crutch. There I was on my hands and knees, like I was still a year old and didn’t know how to walk, when the door opened.

My father walked in. My mother was holding his arm. Her eyes were glistening. He’d flown straight from Washington in an army plane going on to Salt Lake City. The pilot who was flying the plane was a friend of my father and had circled our ranch and come down behind the barn where the meadow is straight and even clear to the crick; and afterwards he took off again for Salt Lake City.

“Hi, Johnny,” said my father, looking down at me. He seemed bigger than I remembered him to be, lots thinner. His hair was gray around the sides. There was a big ugly red scar he never used to have down from his cheek to his chin, nearly. But his eyes were just as laughing as ever. His voice had that same funny deep sound in it I used to remember it had when he’d come up and hint around that we might take a Saturday off to go fishing or for a tramp up into the montagnes.

I was so excited seeing him that I clean forgot about my leg.

I got about halfway to him and my mother, too, when it was like having someone open a trapdoor underneath me. Probably I’d have gone on down clear to China if my father hadn’t given a jump. He grabbed me. He picked me up and carried me to the sofa and laid me down there.

I guess I have to stop now. Tomorrow night I’ll write some more. I’ll tell you why my father hadn’t answered our cables and why he’d come back for only a short time; and what he decided to do, after listening to my mother, and hearing what Mr. Collins proposed to do with the ranches. And, oh, yes, I’ll explain what Dr. Medley said about my leg.