2

THE MAN WITH THE CROOKED BEARD

On Saturday I heard the news.

We were going to France! All of us. My mother and my father—and me. It was like falling off a horse again to hear such a thing as that. Falling off a horse? A house. A whole skyscraper.

You see it happened this way: Almost a year ago, my father had been pretty badly hurt when a German shell exploded near him. He’d written us he’d been in the hospital but we never realized it had been anything very serious. He’d almost lost an eye and he would carry that scar on his face the rest of his life.

After he recovered, he wasn’t strong enough to go back to his outfit—and I guess, not being able to rejoin his men nearly killed him. But anyway, after he was released from the hospital he was transferred from his outfit to Paris. He had to work on what he called “liaison”—which is a French word, I think—helping our army staff in Paris tie in their plans and actions with the British and French. My mother’s family name was Langres. Her mother and father had died when she was a little older than I am now. She’d come over here to live with an uncle in New York, who was an importer, and go to school; but her brother had been too young for any traveling, only a baby then, so he’d stayed in France to be brought up by friends of the Langres.

I’d never seen my oncle—as the French call it—Paul; but by now he was about twenty. This may seem like a roundabout way of explaining something but it isn’t. Even though my oncle Paul was only fifteen or sixteen when the Germans took over France, he had managed to escape from the pre-engineering school he was attending in Paris and run away to the montagnes and join other Frenchmen who kept on fighting. Toward the end of the war, my father told me, my oncle Paul had done some flying, even.

Well, when my father went to Paris, he ran into Paul who had been hurt and had been in a French hospital and now was out, acting as a French liaison officer between the French command and the Americans.

Although my oncle Paul was the only man remaining of the Langres family, he had important friends in the French army, who had been friends with my mother’s father—that is, my French grandfather who’d been a colonel, too, only in the last war. In addition my oncle Paul knew how to speak the English language that people like me and my father and my mother and everyone else I knew spoke before I was taken over to France. He introduced my father to his friends.

As a result, I gather my father found he had a whole barrel of new friends in Paris. Some of them were pretty high up. Consequently, when the American army heard about that, they said that was helpful. They kept him on his new job. They never did let him go into Germany with his outfit. After the Germans quit they asked him to keep on, and help clean up all the details that follow any war. They gave him a furlough of one month to return home; and the reason he hadn’t ever replied to our cables was, first, he planned to surprise us; and second, when mother’s and Mr. Collins’ last cables were sent, he was on the way to us.

He told my mother he was expected to stay in France for at least another year. You can guess that news made my mother pretty sad. But he told her he had more news for her: With the war ended now for nearly a half year, ships and airplanes were beginning to take regular passengers back and forth, between our country and Europe. He said he’d talked with Washington, D.C. There wasn’t any objection if mother and I bought tickets and went over to Europe and took a house in Paris and lived there to be with him.

Another thing, he said, when he’d learned about my leg, he’d discussed it with the army doctors over there. There was a colonel named Colonel Melvon, in the medical corps, in Paris. Father knew him. And, father said, this Colonel Melvon was supposed to be the greatest expert on bone surgery and bone troubles we had. At that, my mother started smiling. This was the same doctor that the doctor in Salt Lake City had said I should see in New York. So before coming back, my father had talked with Colonel Melvon and arranged for him to look at my leg and see what was wrong providing my mother and I came to France.

And that was the news.…

You never saw such a stirring in all your life. Of course, my mother had known we were going for nearly a week. My father had arranged with Mr. Collins about the ranch. Everything was attended to. On Sunday we even had a big dinner with half the county there, I guess. But all that time I’d been doing a power of thinking.

One thing, until my father returned and I knew we were going on the trip, I hadn’t ever thought of my mother as being French.

Sometimes when I’d see her out of my window, watching her swinging along toward the barn or toward the corral, holding my father’s hand, it was almost like seeing two other people down there and not my own father and mother. I can’t exactly explain. They’d be laughing and talking away, sometimes in this new funny language they had together; and, it was as if somehow they were a couple of kids not so much older than I was, and they were all interested and wrapped up in themselves and their own plans, and they forgot they had me, too, that I belonged with them. I’m not explaining very well, I know. The fact is, of course, with my father gone away for three years I’d gotten too used to hanging on my mother’s apron string. After having that accident with my leg, I was cottoned to and sort of babied. Although I don’t like admitting it in writing, I’d not only been spoiled but lost a lot of my gumption.

Anyway, I had the sense of this strangeness. It was coming to me, along with the idea of being uprooted and taken over to France where some fellow over there was going to twist my leg around.

Finally, I told my father I didn’t reckon I wanted to go. I told him that the day before we were going to take the train. He didn’t say much. He just looked down at me, with that scar red and jagged on the side of his face. He looked down and studied me for a long time, maybe three or four minutes. It sort of scared me. His eyes weren’t even laughing. Presently he said something so queer I didn’t understand it then—and it was a long time before I did.

He said, “Johnny, did you ever realize a war can cause casualties away from the front line as well as on the front line? That is one of the things so terrible about a war. It can reach out and hit behind the lines where soldiers are fighting. Sometimes it can reach clear back and hit a man’s home and hurt the people in his home he loves best. In a way, Johnny, you’re a casualty of war, too.”

I said, “Me?” and tried to laugh because I thought he was joking but he wasn’t joking. He was quiet and serious. I said, “Thunder. I just fell off my pony. That isn’t like being shot at.”

He said, “It’s more than just falling off a pony. In the hospital in France I saw men a lot sicker than I hope you’ll ever be and they hadn’t even been touched by bullets. They’d been wounded but you couldn’t see any wounds on them, Johnny. They’d been hurt inside of them, by the war. In a way, something like that has happened to you. We’ve got to get your leg fixed but that isn’t the important thing.” He started smiling. “We’ve got to get you to want to run on your leg, even if it hurts you to run for a time. We’ve got to get you to want to see new people and have new experiences instead of depending on your mother and me, and staying shut up in a house and—” He halted a minute. Then he said, “We’ve got to work out some way for you to go on your own again and not be afraid, just like when you weren’t much higher than my knee and you set across the room on your first steps with neither your mother or me holding you, although both of us were scared you’d fall and hurt yourself.”

I said, “I bet if I had a bicycle I could pedal around and—”

He laughed, “Maybe we’ll fix it for you to have a bicycle, Johnny, someday, but not right now.”

We took the train Monday with everyone at Piedmont to see us off. I can’t tell you how I felt as I saw the montagnes slip away behind us, and all the land and the meadows and the town go off toward the horizon.

We got to New York and stayed at a big hotel. I never saw anything of New York except through the windows of our taxi and through the windows of my room. My father had some army doctors come and look at me. They handled my leg. I don’t like to tell how I acted. It’s all right to say I was nervous and excited, I suppose, as an excuse—but it was more than that. What I wanted was to be back in my own room on the ranch with my mother bringing up my food and reading to me and feeling sorry for me and making everything easy, or with Bob coming over, and being sympathetic, and letting me have my own way because his father’d told him I was sick.

I upset my mother, too. For about the first time I can remember, my mother and father nearly quarreled. My mother said, “But, Richard—” which is my father’s name. “But, Richard, those Army doctors were very rough with him. After all, Johnny’s only a little boy.”

“A little boy?” said my father, his voice going kind of queer. “He’s almost thirteen, and in another three or four years, the way he’s starting to shoot up, he’ll be bigger than I am. Those doctors weren’t rough on him. They were busy. They came up here to look at him as a favor to me, my dear.”

“Perhaps,” my mother said, “we shouldn’t plan to go to France with you, Richard. Perhaps we’ve made a mistake to do this with Johnny.”

My father got a gray sort of sadness in his face. “I’ve been gone a long time, haven’t I?” he said; and that was all he said.

He walked out of my room. My mother looked at me and went out. After a little while she came back and she looked at me again. Her voice wasn’t quite as soft and sweet as it generally was when she said, “Johnny, these last three years while your father has been away, I have tried to do the best I can for you. But if ever I hear you shout and scream again, just because a doctor is trying to examine your leg, and say it was all your father’s fault because he came back and made you leave Wyoming—if ever” she said, “you do such a thing again, I won’t speak to you. I’ll never speak to you. We’re going to France. I want to go to France. Even if you don’t seem to, I want to be with your father!”

After that, somehow, something changed between my mother and me. She remained just as sweet and pleasant as ever, but it was as if a thin curtain or shade had been pulled down between us. The worst part of it was, I blamed my father for it. I know it was wicked of me to think that—but I couldn’t help it. I lay in that bed in New York, most of the time alone while my mother and father were running around in New York, having a gay time for all I knew. I thought how much better it had been back in Wyoming before my father returned, when the whole house and ranch more or less circled around me.

Well, we stayed about four days in New York. Afterwards, my father went to Washington. From there he flew to France. My mother and I had two more days of it, and it was pretty dismal. I wanted to go back home. I said if she’d agree to go back home I’d even let her take me to San Francisco where the doctors there could tinker with my leg.

On that subject she spoke a lot more sharply than she ever did before my father came home. She said it was silly for me to talk that way. I was big enough to understand there wasn’t anything so dreadfully wrong about my leg that couldn’t be fixed. It could go on this way for six months or a year, possibly, maybe two years. There was a chance I’d grow out of the trouble. She and my father had talked about it together, before he departed. The thing was, it wasn’t good for me to stick to bed all the time and wait to see whether I’d grow out of the trouble. The operation wouldn’t take very long; in the hands of a top-notch specialist, the job was simple and—she said—it hadn’t ought to hurt too much. It wouldn’t hurt—she said—nearly as much as my father had been hurt. By having it done in France, we could all be together instead of having the family split up once more. She thought I should be glad to go to France. She didn’t understand why I acted this way.

I turned my face away from her when I said, “Nobody likes me any more.”

Well, you’d have thought that might have brought some sort of response because I felt as low as dust. Do you know what happened? She laughed. Yes sir, my own mother. She laughed. I never heard such a heartless thing.

It was because my father had come back and filled her head with ideas about France and the two had made plans of their own, leaving me out. There I was sick, practically alone in New York, in bed, my leg hurting, wanting sympathy and kindness and maybe a big dish of chocolate ice cream or a promise from my mother I’d get a bicycle—and all that happened was my own mother laughed at me.

Perhaps if I died, they’d think back and feel sorry and wish they hadn’t acted as mean as they had. After I died, I’d probably haunt them. It would serve them right.

I nearly did die, too, on that boat, although nobody but I realized it. I never have been so almighty sick in my life as I was on that boat going to France. Sick? Now I’m writing it down, even at the thought of how sick I was, I turn green around the gills and wish I hadn’t eaten so much tonight for supper.…

The ship’s doctor said I had to expect a touch of seasickness. He said he guessed almost everyone had it now and then. That man was the most casual person about sickness I ever did see. He seemed to think being seasick was something ordinary and cool like having a case of measles or scarlet fever or something on an even lower level.

At least my mother worried. She changed around when she saw I was likely to die and stayed up with me all the second night. I think maybe she had melted enough to promise a bicycle if I hadn’t gotten hungry and told her, the third day, what I wanted was a couple of pieces of that mince pie and some ice cream they were serving for dinner. You’d think a proper mother would realize, wouldn’t you, that a fellow can still be sick enough to die, maybe, and yet be starving to death, particularly for hot tantalizing mince pie?

Anyway. It was a mistake asking for the mince pie. I can see that now. Mother’s eyes flashed sparks. She said she understood better than ever what Richard—that is, my father—my mother wasn’t like some mothers who go around saying “your father” in the same tone of voice they’d say “your bicycle” or “your trousers need scrubbing,” or “your teacher is coming to dinner,” but she called my father Richard when she was speaking about him to me as if he was somebody important and real and human and—come to think of it—he was all of that. Where was I?

Oh yes. She said she understood better than ever what Richard meant about me needing to get well all the way through.

She said she hated wars. She said she hated wars for many reasons. One of them, not the least, was that wars split up families and did things to families but the Littlehorn family—which was our name—was one family that wasn’t going to be licked by a war. When she said that she put down her foot hard. She said, “Do you understand, Johnny Littlehorn? Your father wasn’t licked. I’m not going to be licked. And you’re not going to be licked.”

I didn’t get any mince pie that night. I didn’t get mince pie or a promise to be given a bicycle. When I was sick again that night and yelled for her, where she was sleeping in the next stateroom, do you know what she did? She closed the door. That’s what she did. She closed the door. Although I yelled some more she kept the door closed, and I got so mad I guess I forgot I was seasick. The rest of the night I just thought about how my mother and my father were changing on me, and felt sad and sorry for myself, and homesick, with the ship we were on going up and down, creaking to itself, sloshing through the almighty blackness toward a place hundreds and hundreds of miles away.

My father met us at a town called Cherbourg. I won’t try to tell you what a French town looks like yet, because I was too scared and worried about what was to happen to me to care anything for French towns or the special smells that French towns seem to have. They lugged me on a train which was less than half the size of our trains, with a little engine up front; and we got to this city that was Paris. They carted me out to a hospital and I was there for nearly two weeks.

Father and mother had taken rooms in a big hotel. After two weeks I was moved to one of these rooms in the hotel. The doctor who had worked on me, a little short white-headed man, Colonel Melvon—he came to the hotel a day or so later.

This time, though, he was in uniform. He didn’t have his white clothes on. And somehow the hands didn’t look as terrifying as I’d remembered them from those days in the hospital. They were still big, but they looked worn and thin, with brown spots on the skin. They were old hands. The yell slid back down into my throat and vanished. I found he was kind of smiling at me, and he said, “Johnny, I’ve come to tell you good-by. I’m on my way home. Are you feeling any better?”

He was smiling still more. Something in his eyes seemed to reach out to me. It was as if there was a special secret between him and me. He knew I was lying to him. He knew I didn’t feel any better and never expected to feel better and the pain and hurt would always be in my leg, forever and ever.

He bent over and said, “I want to tell you something. That’s why I came. Johnny, your leg is as good as an old man can ever make it. I can’t do any more. From now on it depends on you whether you’ll be able to run as well as you used to run. I can’t help you. Your father, he can’t help you. Your mother can’t help you. If anything,” he said, and he said it thoughtful and slow, “if anything, they’ll hinder your getting well, Johnny. That’s a funny thing for me to say, isn’t it?”

I didn’t answer.

He wasn’t talking so much to me now, I could see, as to my mother and father who were in the room listening.

He said, “If they try to help you too much, they’re liable to prevent you from recovering completely. They can’t baby you, Johnny. If they do that, you’re done for. You’ve got to want to get up. You’ve got to want to walk and run, no matter if it hurts like blazes. You’ve got to want to run and jump and make that leg of yours adjust itself to acting like a normal leg again and make that brain of yours realize the same thing. Good-by, Johnny. Good luck.”

I blamed Colonel Melvon for the decision my father and my mother reached. My father was to go to England for a couple of months—not right away, but in a few weeks. He and my mother talked over what Colonel Melvon had said. They concluded England wasn’t the place for me. I should be in the country, with sunshine and trees and grass. My father would have to stay in London.

They proposed sending me down to St. Chamant, in the middle of France. The first I heard of it was a few days later. My mother opened up the subject to me. She said she’d received a letter from her brother, Paul Langres. He was finishing his military work. He was in a city called Rouen, somewhere north of Paris, and planned to come to Paris in a week or so to see us, just as quickly as the military people would allow him to go. He was eager to see all of us. He’d written, after visiting us, he planned to return to St. Chamant, where he and my mother had been born. He hadn’t been back to St. Chamant since the war had started. He wanted to stay there during the summer and part of the fall to rest and work on one of his projects and he suggested perhaps we’d like to go with him.

Well, that had given my mother an idea. She’d written to ask him if I could go with him and stay with him in St. Chamant. Of course, I protested. I wanted to be with my parents. My protests didn’t do much good. My father thought it would help me. A day or so later, mon oncle wrote back and said he’d be delighted to take me.

I complained I wouldn’t be able to walk or move—and I’d be a bother to him. By now, you see, I’d become accustomed not to move. As long as I remained in bed or stuck to a chair, it was all right. And all I wanted was to go home. I didn’t even receive any enjoyment when my father brought home a collection of German coins for me. You can see how low I was.

The only friend I had was the hotel porter, Albert. My father had hired him to wheel me around Paris, hoping I’d pick up and find more interest in life once I got out of the hotel room. I told Albert how I might have to leave my parents and go down to a little no ’count French village. Albert spoke English, although he didn’t speak it very well. He was fat with tiny eyes and puffed like a leaky kettle as he pushed my wheel chair.

“I’d rather die than be shoved off to St. Chamant,” I said.

“St. Chamant?” he said, stopping.

“That’s the name of the place,” I said.

“St. Chamant?” he said once more, his voice having a squeaky sound to it. “You say it iss St. Chamant, Master Littlehorn?”

I said, “Sure. My mother was born there. She was a Langres.”

“A Langres?” he said, the same way he’d said the name of the town, as if he was echoing me.

I twisted around at him. His mouth was open. I said, “My uncle’s Paul Langres. He ought to be here in a couple of days. You don’t know him, do you?”

“Know him? Ah, no,” said Albert, giving my chair a jerk as he started pushing it. “For why should I know him?”

“You haven’t ever been to St. Chamant?” I asked, hoping he had.

He shook his head. He said he’d never heard of it before. A little later he explained he’d been surprised to hear I was going because he enjoyed wheeling me in the chair and that seemed a reasonable explanation too. I said I wasn’t sure I was going. I was going to get out of going if I could and he supported me in that. He said he didn’t believe a lame boy such as me would enjoy being away from his parents. Well, that didn’t hit me exactly right. I allowed I could exist without my mother and my father for a couple of months. But he went on and sympathized and pitied me and I began to feel sorry for myself. That night I argued louder than ever against going.

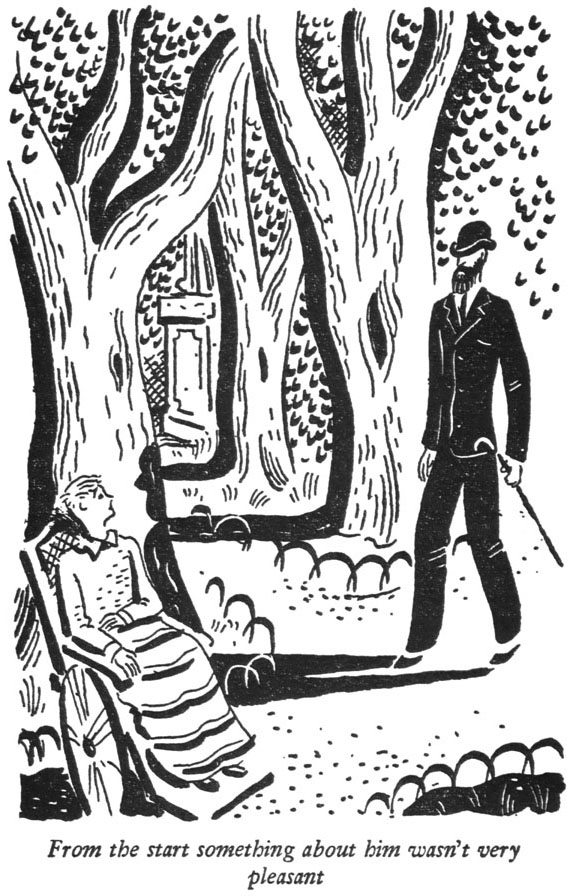

The following day Albert wheeled me into a little parc. He asked to be excused a few minutes. He said he wanted to buy some tobacco across the street. A tall man happened to walk by me and went on and returned and sat on one of those iron benches the French have in parcs. He was one of the tallest men I’ve ever seen, all bones, with a white face and a beard that was lopsided. I mean, it grew thicker on one side than the other. He had greenish eyes. He watched me with those greenish eyes. They made me uncomfortable. I wished Albert would hurry back.

He noticed my legs and my crutches. Pretty soon his eyes became soft and round. He hunched over toward me, the dark cloth of his suit wrinkling on him. I wanted to draw back. From the start something about him wasn’t very pleasant although he did his best at first to be easy and friendly. “Bon jour,” he said, in a voice soft as mucilage.

I said, “I don’t speak French.”

At that, his eyes opened wider. “Don’t you now?” he said, in English just as good as mine. “I’m surprised at that, my young friend. If I had a son as intelligent as you appear to be, I’d quickly teach him French and take him with me and show him a good time instead of foisting him off with a stupid hotel porter.”

It never occurred to me to ask him how he knew I was with a hotel porter.

My first feeling against him changed as he continued talking. He said he had a son who was lame, too. His son was in Marseilles. Telling me about his son more or less broke the ice between us. He said he was here in Paris on business and felt lonesome. He didn’t like the people in Paris. I replied I didn’t either. He smiled, all the sharp yellow teeth showing. Just for a second again I had that odd feeling toward him—but right away it passed. I forgot it as he told me how easy it was to learn French. “Now, take what I said. I said ‘bon jour’ to you. That means ‘good day.’ ‘Bon’ is ‘good’ and ‘jour’ is ‘day.’ You observe how easy it is? Bon jour. You say it.”

So I said “good day” in French. I said, “Bon jour.”

“There,” he said, very cheerful. “It is easy?”

Albert seemed to be taking his time getting tobacco. We must have talked about fifteen minutes. The tall man said his name was Mr. Fishface—that’s right. I didn’t think I’d understood, either. He repeated it, calm and placid. He didn’t appear to realize it was a funny name. He spelled it for me: “Fischfasse,” which was French. I don’t think he knew it was an almighty funny sort of name in our country. I managed not to laugh, though.

He said his son was coming to Paris in a few weeks. He hoped we could meet. His son was fifteen years old and knew English. Of course, that pleased me. Then—I remembered. I said I didn’t think I’d be here. He lifted his eyebrows.

“My parents want to shove me off to St. Chamant with my uncle,” I told him.

“Oh,” said this Mr. Fischfasse. “St. Chamant? You and your uncle will live there?”

“I expect so. I don’t want to go, though.”

“Ah,” said he, “no wonder. A dull little place.”

“You’ve been there?” I asked.

“No,” said he, “no, I have not been there. But I have friends who have passed through it. I am surprised any parents would send their boy there.”

“My mother was born there,” I explained. “Her family had a castle there or something. I expect my uncle and I will live in the castle.”

I don’t know why I stuck that part in about the castle. I shouldn’t have. It was stretching the truth considerably; and later I paid for it. But he had kind of sneered when mentioning the town my mother came from. I didn’t like that. I wanted him to realize my mother’s people and where she lived were important, even if the town wasn’t.

“You’re going to live—” He broke off. He got up, joint by joint. “I must go now. Perhaps if you are here tomorrow we shall see each other again, Mr. Littlehorn. I will teach you a few more French words and you’ll surprise that good father of yours.” Then, he said, “Bon jour,” and off he went.

I replied, “Bon jour,” and waited for Albert to arrive and take me back to the hotel.

That evening, I started to tell my mother and my father I’d run into a Mr. Fischfasse, but they never let me finish. My mother said, “Why, Johnny. You mustn’t call people names like that.”

I said, “I can’t help it. That’s his name. He looks like a fish, too.”

My father laughed. “Johnny, don’t let that imagination of yours run away with you.”

I said, “But I did—”

My father laughed again. “You’ve been cooped up in bedrooms for so long you’ll be seeing giants and monsters, too, if you don’t be careful.”

And my father and mother got to talking, again, about shunting me away from them. I didn’t care to hear any more about it. I dragged off to my bedroom. Here, I tried playing with my coins. When my mother came in to put out the lights, I asked, “Did you live in a castle in St. Chamant?”

She halfway smiled. “It wasn’t a castle, Johnny. But it was a very wonderful house. I haven’t seen it for years. Paul hasn’t either since the Germans attacked France. I hope they haven’t hurt our house too much. I shall want you to see it. Good night.”

I tried my French on her. “Bon jour,” I said.

This time she smiled all the way around. “Why, Johnny. Bon jour. But when it’s night, you don’t say ‘bon jour.’ You say ‘good night’ or ‘bonne nuit.’”

I tried that on my father a little later. He understood it and grinned and replied, “Bonne nuit, Jean.”

I asked, “What’s that last word?”

He said, “Jean?”

I said, “Yes sir. That one.”

He answered, “That’s you. ‘Jean’ is your name in French. ‘Jean’ is ‘John.’”

Well, that did it.

I didn’t mind trying a couple of words in the lingo but when I heard the French had gone and changed my own name to Jean it was too much. I was through talking French. I was finished. I said, “Father, can’t we go home now?” I said, “Please.”

He stopped smiling. His face got the same tired gray look it had before we started saying “Bonne nuit” to each other. He shook his head. “I’m sorry,” he said. “The government has made me an officer in the army and I have a duty and I can’t run from that duty, can I? If I’m ordered to report to London on the Allied Aviation Committee it’s my duty to go and not complain. I’m sorry.” He shook his head and said, “I’m very sorry, Johnny.” He turned off the light and shut the door. He’d sounded sorry, too. I won’t ever forget how sorry he’d sounded. It was as though I’d done something to make him sorry.

I couldn’t go right to sleep. I thought about the French changing my name into “Jean” and how queer names were and about Mr. Fischfasse and all at once I remembered he’d known my name. He’d called me “Mr. Littlehorn.” I couldn’t understand that. He hadn’t ever seen me before. I hadn’t told him my name, either. I couldn’t get over it. I was bothered. I went to sleep and had dreams about him, only he was like something made out of dry wood in my dreams, about a mile high, his white face stuck on top of the sticks, like a dead fish.