6

LA MAISON DE TA MÈRE

That nuit I wrote my first letters from St. Chamant: one to my mother, one to my father, and a third to Bob Collins, back in Wyoming. I told my father I’d walked all the way from the station and everything was going fine although at present there weren’t any boys my age to play with. I asked him if he’d had time to look at any English bicycles with high gears and low gears.

In the letter to my mother, I wrote about le train and the trip down, although I didn’t mention seeing Monsieur Simonis on the train. The fact is, now I was away from them, I’d had time to think over how I had been acting in the past. I was ashamed. I wanted them to believe I was growing up and recovering from being so easily scared and I was determined to make my letters to them cheerful if I choked doing it. They had worries of their own. I hoped mon oncle wouldn’t write them, either, and inform on me, how I’d been frightened by the wind blowing against a window. I should have asked him not to—and I decided tomorrow to ask him if it wasn’t too late.

I ended my letter to my mother with French words I knew, such as: “C’est bon here in your village de St. Chamant … Mon oncle est giving me leçons in French … Le jour est beau although it rains a lot … Où are you now, in London? … Jean va to bed …” and things like that.

To Bob Collins, back home, I wrote a longer letter. I stretched the truth here and there a shade, I’m afraid, because I wanted him to believe I was having a gaudy time of it. I told him probably I’d fly mon oncle’s avion. I wouldn’t be surprised, from the way I described the avion, too, that he might have obtained an idea a motor was in it.

I went to sleep afterwards, and didn’t have any dreams, either. Along about morning, I awoke. The sky was pale and cold. You know how it is when you awaken very early in the morning, and are still half asleep, the bed warm and comfortable. Probably I was almost dreaming. The front windows were open. As I lay there in bed I imagined I heard someone passing by in the street, humming. That was all. I listened; and the tune hummed sounded familiar. I remembered—all at once. It was the same tune Albert used to hum, meaningless and senseless, when he pushed me in my wheel chair.

Once again, the coldness came over me. I forced myself, this time, to go to the window. I looked out into the cold dim light. All I saw were a couple of men of the village going off to the fields, their rakes and hoes over their shoulders. I felt silly. Anyone of them might have hummed that silly old tune. I crept back into bed, wishing I were well, like other boys, not ready to jump out of my skin with fright at nothing.

I had breakfast downstairs in the big front room. Evidently, mon oncle had already eaten and had gone to work on the avion. The two kids ate with me. We had bowls of brownish mush, topped with goat’s milk. I wouldn’t even have looked at such truck at home. Here, in the montagnes, it must have been the fresh clean air that made a body so hungry. When I was finished, the boy, Philippe, began chattering at me in French. I needed mon oncle to translate, but I couldn’t even ask if he’d gone to work on his avion.

Finally, I remembered. I said, “Où est mon oncle?”—that is, “Where is my uncle?”

Madame Graffoulier answered, very slowly, “Ton oncle est avec le forgeron.” I knew every word except that “avec” and it slipped in like the last piece of a jigsaw puzzle. The only thing it could mean was “with.” My oncle was with the blacksmith.

I nodded. I said, “Bien!”

The boy pointed to himself. “Philippe,” he said.

I pointed to myself and said, “Jean.”

Philippe took my hand. He asked, “Ton oncle va voler?”

I knew that one too. “Your uncle is going to fly?” he’d said. I nodded and replied, “Oui.”

Next Philippe asked, “Tu vas voir ton oncle?”

That “vas” was understandable; it was the same as “va”—which was “is going.” So “tu vas” was “you are going—” but I was stuck on “voir” until Philippe pretended to look all about the room, saying “voir, voir,” at the same time. It came clear. “Voir” was “to see.” He’d asked, “You are going to see your uncle?”

“Oui,” I said, again.

Philippe asked, “Philippe y va, aussi?”

It wasn’t difficult after all. I remembered “aussi” was “also.” And I supposed “y” must mean “there.” So I said, “Oui, Philippe y va aussi.”

Out we went, into the deserted street, Philippe leading me toward the blacksmith shop. As we walked, I pointed down to the street and asked, “Qu’est-ce que c’est que——?”

“Ça?” said Philippe.

That stumped me for a minute. I knew “ça” wasn’t the French for “street” because of the way he put a question after it.

I pointed again at the street.

He understood. “Ah,” said Philippe, mighty pleased. “Ça? C’est la rue.”

“La rue?” I asked. That was what a street was called in France.

“Oui,” said he. “C’est la rue.”

We walked along la rue until we reached le forgeron’s. There was mon oncle talking to Monsieur Niort. “Bon jour, bon jour!” cried mon oncle. He saw Philippe and clapped him on the shoulders. He said something to him in French. Philippe laughed. He pointed to me and explained. Both mon oncle and le forgeron laughed.

Mon oncle said, “Now Philippe teaches you French, aussi?”

I said he’d told me “la rue” was a street but I didn’t understand exactly. Was “street” two words in French, both “la” and “rue”? Well, mon oncle explained that easily. “La” was another word for “the.” That puzzled me. I never knew a language to spell “the” two ways. It meant that in French both “le” and “la” were the same thing? He nodded. “Oui, c’est ça.”

I asked, “What is ‘ça’?”

“‘Ça’?” said mon oncle. “‘Ça’ is ‘that,’ for pointing out something. For example—” He pointed to the street. “Ça est la rue.”

I got it. I said, “Oui, ça est la rue.”

He pointed to a house across la rue. “Ça est la maison.”

I said, “Où est my maison?”

He waggled his long nose. He stepped outside and pointed up la rue toward our little hotel. “Là—there. Là est ta maison. You understand?”

That ended French leçons for this jour. Mon oncle asked how I’d slept last night. I said, “Fine,” not wanting to admit I’d been briefly scared early this morning, thinking I’d heard Albert pass below my window, humming. I inquired if he’d received a letter from the Paris police yet and he said it was too soon, but he expected it before the end of this week. Next, I worked around to asking if he’d written my mother how I’d acted the night before.…

He laughed. “It was such a little thing, already have I forgotten it. I do not think ta mère—your mother—would be interested. We both forget, n’est-ce pas?”

That cheered me a lot. I knew he was on my side. At the far end of the next building a couple of workmen were laying pieces of wood on a table, joining them. Mon oncle explained this was to be one of the wings. Over to one side he showed me a huge brass pan, big around as a cart wheel, filled with hot water. In here he was steaming other sections of wood in order, tomorrow, to clamp them in forms which bent them into the shape of ribs.

All this time he had been regarding me with a peculiar expression on his face. Suddenly he asked, “Where are your crutches?”

Until that moment, I’d forgotten all about them. I’d walked the twenty or so yards from the hotel to the workshop on my own power, being so interested in learning the French words for street and house. A funny thing happened: the minute mon oncle reminded me of my crutches my leg felt weak, and began hurting. The pain got bigger. Probably I had strained it a little. I was scared.

Mon oncle sent Philippe back for the crutches and the rest of the jour I stuck to them, as usual. Late that afternoon, Dr. Guereton dropped in and examined my leg again. He chirped cheerfully and looked over his square glasses at mon oncle and appeared satisfied nothing had been damaged.

In the evening, the men returned from the fields. After dinner, mon oncle had me down with him in the courtyard. Monsieur Niort played on his accordion. By and by, the people there persuaded mon oncle to join in with the flute. All sang French songs and some of the younger women danced folk dances and it was pretty and cheerful and I hated being sent up to bed because it was so late.

In my room, instead of going right to sleep I got out my German coins and wrote Bob another letter, asking him to find out how much German coins might be worth. I told him I was living in a place where people had picked up old Roman coins and I meant to keep my eyes peeled. I’d like to find a Roman coin, myself. The wind made its sound. As I wrote, it seemed to me there was another sound outside, in addition to the wind. I opened the window and looked out. A long shadow flickered against the opposite wall and then it vanished; it was gone. It was as though a man had been standing across from the hotel, looking up at my lighted window, humming to himself.

I got as far as the door to yell to mon oncle and returned. I knew I was wrong to imagine things so easily. I mustered up all my courage. Once again I stared out of the window. All I saw was a pear tree scraping against the wall over there. The moonlight made it throw a shadow. I was glad I hadn’t yelled for mon oncle this time. I got undressed and lay in bed for a time and by and by I got up again and locked all my windows. After that, I went to sleep.

For the next week or so nothing much happened. Nearly every jour now, mail brought a letter from my mother or father. In her last letter, my mother wrote they were hoping to take a little vacation, themselves. My father’s work had progressed more rapidly than he expected. He had asked for a two weeks’ leave to allow him and my mother to take a walking trip through Scotland.

My mother said neither of them would go if it worried me in the slightest to know they might be out of touch with me for a little while. She wanted me to write and let them know. I did, too. It seemed to me both of them had earned a vacation. I said of course I’d like to be with them but I couldn’t do that much walking yet although I hoped to be able to, sometime. I said everything here was going along wonderfully and mon oncle was about a third of the way finished with his avion. They could take the vacation any time they wished. I mailed that letter the next jour and I was pleased I’d recovered enough not to be scared if they went walking in Scotland where I couldn’t telegraph them and receive a reply right away. I hoped they’d go.

Mon oncle and le forgeron were busy with the avion, working like beavers. That boy mon oncle had spoken about—Charles Meilhac—he never did appear. I gave up expecting him. In the daytime the village was deserted. The men were in the fields, the women working in the houses. I did meet more younger kids, but they weren’t much fun. Philippe continued to tag after me as if I belonged to him. At the far end of the street I discovered two girls about my age. But they weren’t interested in me and I wasn’t interested in them. About half the time it rained.

I pestered mon oncle about the letter he was to receive from Paris. He didn’t get it, although time dragged. He wrote a second time, saying perhaps his friend had been away and was too busy to think—“zink,” he said—of writing about a trivial matter such as questioning a hotel porter.

I practiced walking more. I felt better, too. I ceased dreaming about Monsieur Simonis. Mon oncle had asked the mayor about him. But the mayor flew off into a temper. He claimed he never sent a business agent to Paris to buy property—and, privately, mon oncle told me he didn’t believe the mayor. He said the mayor probably had gotten into a rage because he was discovered, and had lied.

From Philippe I learned more French, too, not forgetting the bargain I’d made with my mother—ma mère, I should say. I learned, “Voici Jean!” meant, “Here’s John!” More than once Philippe asked me, “Jean va voir la maison sur la montagne?” Finally, I got on to the fact he was asking if I was going to see the house upon the montagne. That “sur” was French for “upon.”

I was waiting for mon oncle to take me to the house where my mother was born, but he had to apologize and explain that at present he was in the middle of attaching ribs to the wings of his avion, and couldn’t take the time. He promised he’d knock off for an afternoon in just a few jours. He said the waiting wouldn’t be wasted because it gave me time to practice walking and put more strength in my leg. He explained the house and land was up on the montagne. It would require a tolerable climb for us.

Along toward the third week, I received a shock. The letter from mon oncle’s friend in Paris arrived. It was a long letter. After dinner he went up with me to my room and shut the door and admitted the news wasn’t what he expected. The police hadn’t been able to locate Albert. He had vanished. Mon oncle stroked his nose and looked at me, pausing. He said that wasn’t all there was in the letter. I waited, feeling a funny shiver pass through me.

The man, Monsieur Simonis, wasn’t a Frenchman at all, according to the police. According to the description I’d given mon oncle which he had passed on to his friend in the police, Monsieur Simonis was a German agent who’d lived in France and pretended to be a Frenchman. A couple of times they’d almost nabbed him—and each time he had escaped. His real name was Heinrich Simonz.

“Oh,” I said, pretty weakly, too.

The police had a theory I’d brought most of the trouble on myself in Paris by chattering away to Albert during those afternoons, telling him my mother was French and had been born in St. Chamant and had a castle there. They figured Albert was in cahoots with Simonis and that Simonis was pretty desperate and needed money. All Europeans, you know, think Americans are rich. Of course that isn’t so, but Europeans don’t understand. According to the Paris police, Simonis had learned about me from Albert. The two planned to grab me and hold me for money. Simonis had hit upon that excuse to buy my mother’s property, as a chance to see my parents and later on would have come back to them, after nailing me, threatening them with what would happen to me if they didn’t pay and if they went to the police. That was all there was to the whole business. The police said they were sorry they hadn’t learned about it sooner. They didn’t think either Albert or Simonis would go very far before being captured. They thought Simonis had been heading south toward the montagnes, to hide in them, and when he saw us on the same train had jumped off, more scared than anything else.

Mon oncle folded the letter. “Voici,” he said. “I am better at building avions, I zink, than making guesses on police matters.” He smiled. “Ah, and that poor Mayor Capedulocque. I have worried him needlessly. No wonder he was so very angry. I suppose now he zinks somebody else is also attempting to buy our land. He will be very worried. I hope, very much.” The smile broadened. Mon oncle enjoyed thinking about worrying Mayor Capedulocque, who had been causing trouble the past few days, trying to have mon oncle put out of the workshop. He looked at me. “What do you wish to do, Jean? Shall I write to your father?”

I didn’t know what to do. It might spoil their plans for a walking trip if they became concerned about me.

I said, “Maybe you better not write.”

He shrugged. He went out and came back with his flute and sat on my bed and played for a time, almost as if playing to himself, soft and low. Pretty soon he raised his head. “It is better here, n’est-ce pas? Even without a boy your age?”

“Better than Paris,” I admitted.

“In a day or so, too, I zink you will have a friend. I have heard that Charles Meilhac is expected to return very soon.” He wiped off his flute, polishing it. “I will not write. It is not necessary.” He stood. “Tomorrow, I tell you what we will do. We will visit la maison de ta mère. You comprehend? The house of your mother. It is a promise.”

For all these weeks I’d been looking forward to seeing it. That promise drove any remaining concern I might have had about Monsieur Simonis clear out of my head.

I went to bed early and next morning stuffed myself and for a couple of hours hung around the shop and after an early lunch mon oncle looked at his watch and said it was time.

We were to meet a friend of his, Monsieur Taggart, who was going part way up the montagne in an oxcart. The ride would save our legs. As he spoke, I heard a creaking outside the hotel. A big cart halted, pulled by an ox. A man shouted, “Tu viens, Paul?” Mon oncle lifted me up from the table and carried me to the cart and dumped me into the straw and away we went—at no more than two miles an hour. You can’t hurry an ox.

We took the road past the church and Mayor Capedulocque’s place, his hens and ducks squawking at us from beyond the wall. We rolled up and up, the big wheels squeaking. White clouds blew across the blue sky. We reached a cross-roads in the montagne where the path branched in two different directions. Here, mon oncle jumped off. He lifted me down. Monsieur Taggart waved his hand and called, “Au revoir,” which meant “Good-by,” and we answered, thanking him for the ride.

Mon oncle said, “Now, you and I must climb the mountain. In French, you would say, ‘John and his uncle Paul mount upon the mountain—Jean et son oncle Paul montent sur la montagne.’”

But I remained right where I was, hanging on to one side of an old stone wall, protesting I couldn’t mount sur any montagne without my crutches. “Pouf!” said mon oncle, snapping his fingers. “I shall be your crutch, Jean, for a time. You need more confidence, not crutches.”

For about half a mile more, mon oncle and I moment sur la montagne, going through a chestnut and oak forest. At a turn in the little lane, we came around a ridge. Through the trees we had a vista before us, hills and valleys. Five or six miles to the south were tiny houses and steeples of another village, with the silver shine of a river running by the village. Mon oncle stopped. He said that village was Argenta. The river was the river Dordogne.

Two or three thousand years ago, the Romans had made a camp near Argenta, a big camp. They’d stayed there for centuries, lording it over all this part of the country. He took my head and had me sight along his outstretched arm. I saw a kind of round, doughnut-shaped hill which he pointed out, about a mile southwest of le village de St. Chamant. He said that mound of earth was the site of another Roman camp.

That excited me. I said, “Maybe if I do some digging tomorrow, I could find old Roman coins. They’re super-valuable. We’d sell ’em and make money.”

One thing I liked about mon oncle—he didn’t laugh at ideas, even if the ideas were impractical. Perhaps that was because people had laughed at his idea of building an avion. Instead of laughing, he explained Roman coins had been dug up from around Argenta and in the river and from that big mound near St. Chamant. He admitted I might find a coin—but he said it wasn’t likely. Professors from French universities had spent several summers here before the war, with fifty or sixty trained workers, sifting and sorting through everything.

“Come along,” he said cheerfully. “Viens, mon neveu. Viens voir la maison de ta mère!” And he gave me a lift with his arm. In another ten minutes we crossed a flank of the montagne and came into a meadow, rich and green. Tall shade trees lifted up toward the blue sky. Birds were singing. Except for the birds, everything was silent. It was almost like walking into a church. I followed mon oncle, using his shoulder as a support. Without saying anything, we walked through the tall grass. We came upon a brick covered lane, with blackberry brambles grown wild on each side.

Ahead were the ruins of an old maison. Two sides of the walls were standing, with enormous empty windows and a great door. Mon oncle halted. “Voilà,” he said. “Voilà. C’est la maison de ta mère.”

It had belonged to my great-great-great-grandfather. It was hundreds of years old. The Langres family had lived here all that time, generations of them. They had been lawyers and soldiers. Here my mère had been born. Here mon oncle had been born. This great stone house had been what is called a château—that isn’t actually a castle, but it was something like a castle. It had overlooked the valley. Many of the people in the village de St. Chamant had worked for my grandfather; and, I assume, from what mon oncle Paul told me, for my grandfather’s grandfather, too.

When the Germans came down from Paris they had taken the Langres maison. Before they had departed, they had burnt it. I can’t explain how I felt. Mind you, I hadn’t seen this maison before. But the minute I saw the ruins, it was as though I’d been here many times and knew about it. I know that sounds funny. For nearly half an hour we walked around the grounds. Mon oncle explained the reason he was working so hard on his avion was he hoped to sell it for much money and he planned to use the money to restore the maison and the grounds. Just as I wanted my bicycle with the high gear and the low gear and the electric lighting dynamo, so mon oncle also wanted something—he wanted to rebuild the family home. I could understand now. I could understand a lot more things. I wanted him to get his avion completed and sold. No longer was his avion an ordinary glider, not very important. I felt the urgency of what he wanted.

By and by he glanced at his watch. “Ah!” he said. “It is nearly two-thirty. I’m late, Jean. I told Monsieur Niort I would return to the workshop by two-thirty. Instead of taking the path we came up on, I zink I shall descend straight down the mountain. It is quicker.”

“But—” I was worried. “I’m not sure I can descend straight down a mountain without crutches.”

He cocked his head at me, something like a quick lively fox who listens a minute before darting away. He shrugged. “Then you must descend by the path,” said he. “Descend by the path, mon neveu. You will not become lost. You do not require crutches. It is confidence you require. Au revoir!”

“Wait!” I called—but he was gone.

He leaped over the wall and ran toward the trees and vanished. I hadn’t ever expected him to do a thing like that to me.

For about ten minutes I was so stunned I didn’t do a thing. This was what came of having mon oncle and me montent sur la montagne. I simply sat where I was. The breeze was soft and warm. It was the finest jour we’d had yet. I could sight across the meadow to the edge of trees. Beyond the trees, the montagne dropped away, sloping into the valley below. Across to the west was a range of lower montagnes, purple and green in the distance. Voici Jean, I thought—stuck. I got madder and madder.

By and by I grabbed hold of the rough bark of a tree and pulled myself up. Butterflies floated above the flowers. I limped to the stone wall surrounding the ruins. Here I sat for a time, almost forgetting my leg as I tried to imagine ma mère as a young girl, playing in the grounds when the grounds were smooth and even and tended to, with the noble old house high and stately on the side of the montagne. No wonder she had always thought of France and loved it. In a way, I was glad she wasn’t here to see her family’s house—her family’s maison, I mean, destroyed by the Germans.

The big front door was still here. It had pillars on each side. It was almost as if ma mère was waiting for me, on the other side of that door. I never saw such a friendly, inviting door. I slid off the stone wall, taking it easy on my leg, gritting my teeth. I got as far as the door and my leg still stayed whole; it hadn’t dropped off. It hurt, yes. It hurt off and on but at least it had carried me to the door. I decided I’d stay here and wait. After I didn’t show up in le village de St. Chamant, my oncle would begin to worry. I’d teach him a trick, too. He could come for me.

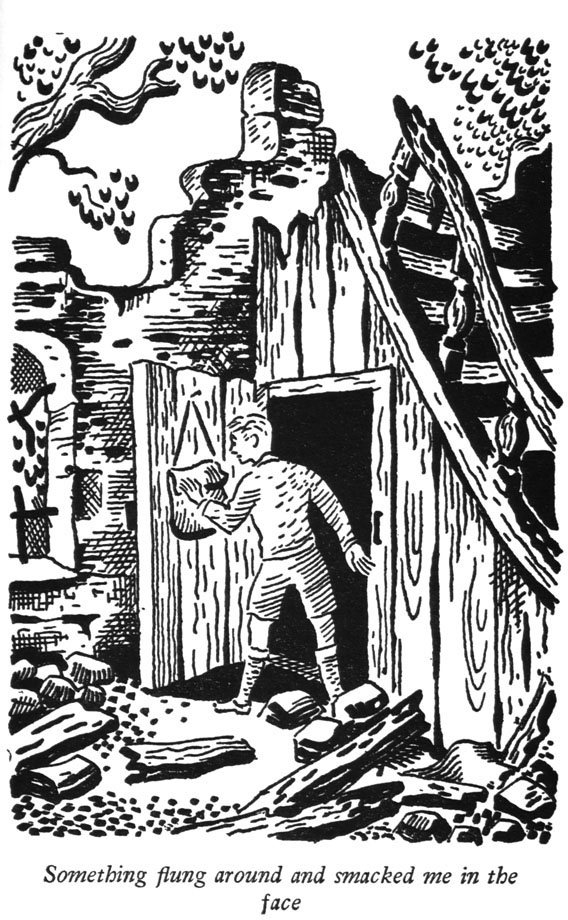

I entered the house, hearing my steps echo. The roof was gone. Part of a big stairway lifted upwards—and ended, abruptly, pointing to the open side. It was sort of fun exploring la maison de ma mère. The wood was blackened from the fire, charred through in places. I followed along the hall, with the sun shining down upon me. I got as far as the stairs and rested and started again around the rear of the stairs. Here, under the stairs was a door. It was on its hinges. The fire hadn’t eaten through it at all. I tried the door; it opened, just as if it had been waiting there for me and was inviting me to open it.

When I opened it, something flung around and smacked me in the face. You can imagine how surprised I was. I wasn’t scared; at least, I don’t think I was. Everything here was so peaceful and friendly, as if I was coming back almost to another home of my own, there wasn’t anything frightening at all about the place. I wasn’t nervous, or anything like that, either. I was mad—sure; but, now I’d determined to teach mon oncle a leçon, I was recovering from being mad.

So, when that thing flung around and hit my face I stepped back, nearly falling, because I’d stepped back on my punk leg. On the other side of the door leading down into the cellar was swinging a dirty gray knapsack. That was what had hit me, swinging around as I opened the door. I thought perhaps this was a knapsack that might have belonged to mon oncle. I looked more closely at it. Words were printed on it. They were foreign words. And—they weren’t French words, either.

One of the words was “Panzergruppe 156.” As if from a long ways off I remembered panzer was a German word from reading about the German panzer columns of tanks in our newspaper back home. If the words were German—why, then this was a German army knapsack! It was like having a cold wind blow clean through me. My hands were shaking when I opened the knapsack. Inside was an old tattered dirty paper-covered book titled “Mein Kampf.” Underneath the title evidently was the name of the author: “Adolf Hitler.” Well, I knew that name all right. Last I’d heard of that name was quite a few months ago when our papers back home had a couple of lines about him on the inside pages saying he was dead, probably having killed himself.

Nothing else was in the knapsack but a whole loaf of French black bread. I touched the loaf of bread, expecting to find it old, solid as a brick. It wasn’t old. It was still soft. It couldn’t have been more than a jour or so old. That meant the owner of this knapsack hadn’t hung it behind the door more than a jour or so ago, perhaps even this morning. Whew! At that thought, I just dropped the knapsack and started to shove out of this place. I didn’t want any Nazi holing up in these montagnes to come upon me; I’d had all the experience with them I needed with that Monsieur Simonis to last me the rest of my life.

I was limping away, when I heard a second and softer clunk. I looked back. The knapsack had spilled open after being dropped. The loaf of bread had rolled out—and do you know what? That loaf evidently had been broken in two pieces when fresh and stuck back together again. The second clunk I’d heard was when the long ugly black pistol hidden inside the scooped out portions of the loaf had rolled on to the charred wooden floor.