9

CHARLES VEUT VOIR L’AVION DE MON ONCLE PAUL

The following jour it was sunny and warm again after last nuit’s rain. Soon as I had breakfast, I headed for the workshop. I took my crutches, mostly by habit. Halfway there I decided I wasn’t going to depend on crutches any longer. If I could descend a montagne without crutches, I didn’t require them on a level rue—street. Mon père had promised me the bicycle avec the high gear and the low gear on condition I was able to walk two miles as well as any other boy could.

By now the time I had to meet that condition was almost a third gone. I figured it was more than two miles from the ruins to le village. I’d gone that far—yes. But I hadn’t met the condition mon père had set. I’d fallen. I’d been helped by Charles and Suzanne—as well as by the kicks from Monsieur Capedulocque. Afterwards, I’d been tuckered out, and stiff as a board. Even so, just getting down the montagne proved to me I still had a chance. My leg was getting stronger. The best thing to help it grow stronger was to stop using crutches. So, I made the rest of the way on my own feet.

Right away, inside the workshop I noticed the workmen were gone. Only mon oncle and le forgeron remained. Sunlight streamed through the windows upon the outstretched wings. By now, the framework to the two wings was nearly completed. If you can imagine a big “V” laid flat on the hard brick floor, the point of the “V” toward the door, you’ll begin to understand how mon oncle’s avion appeared—in French they’d say, I’avion de mon oncle, or—the airplane of my uncle. You can’t beat those French to figure the most awkward way in the world to say something. Same with everything else; the house of my mother, instead of my mother’s house; the pig of the mayor, instead of the mayor’s pig.

Each side of the “V” was a wing. Each wing was about seventeen feet long and six feet wide. The result was like the framework to the most enormous butterfly you ever saw. According to mon oncle an avion built in this fashion, without a tail, practically flew itself. At nuit I’d heard him say, sometimes, he could plant a baby in his avion and shove the avion off, and that baby would be as safe and comfortable as in its own bed. Mon oncle was dead serious, too, when he claimed that. Naturally, every jour I was in a fever of impatience, hardly able to wait to see the avion done and tried out.

This morning mon oncle and le forgeron were occupied attaching spruce ribs to the longerons of the right wing. Four ribs were placed within every foot, all cross-braced with spruce battens and piano wire drawn tight by big turnbuckles. In that shaft of sunlight the partially completed wing stretched out from wall to wall of the workshop. Already it looked like a wing, even without the linen cloth covering which went on last.

“Bon jour, Jean!” called le forgeron in his big booming voice. Mon oncle was holding one of the ribs in his hand while he adjusted a wooden clamp. He gave me a quick smile. I waited until he was finished. He ruffled his black hair. I asked where the other workmen were.

“Oh, the ouvriers have quit,” he said carelessly. “It is of no importance.”

Le forgeron shoved his beard up over the left wing and rumbled, “Jean, tu vois? Pas d’ouvriers. Ce sacré Monsieur Capedulocque!”

The blacksmith had said there weren’t any workers—something I’d already remarked—and blamed the mayor. I asked mon oncle, “You don’t mean the mayor prevented them from coming?”

Mon oncle shrugged. “It is no matter. The mayor has offered them higher wages to work in the vineyards. I shall save my money by having them go. We shall not permit that mayor to see that he annoys us, because it would only please him the more.” He picked up another rib, glancing at me over his shoulder. “He shall not beat us, never! That mayor wishes to be clever. He wishes to wait until he zinks we forget about his dead pig, too. Then he will attempt to surprise us with more trouble. You watch. But we will be ready for him.”

I asked why the mayor had it in for us all the time. Was it simply because he hadn’t been able to buy the Langres property and because I’d accidentally shot his cochon? I didn’t understand. Mon oncle showed his white teeth. He said perhaps it was because the mayor was easily disturbed and enjoyed showing his authority, and I wasn’t to worry—but I did worry.

Mon oncle showed me how I could help, screwing the wooden clamps. He said I could take the place of one of the workmen; and I did, too. But even though I didn’t speak about it again to mon oncle, I worried and wished I could think of some way to stop the mayor from trying to plague us. It seemed to me if I hadn’t ever seen that confounded Nazi knapsack and pistol and excited the village and stirred up trouble that perhaps the mayor wouldn’t be so angry with mon oncle.

For the next few jours nothing much happened. The mayor didn’t say anything more about the cochon I’d shot and I hoped he’d forgotten it. Mon oncle received a letter from his friends in Paris, thanking him for the information that a Nazi might be hiding round about St. Chamant. They said it wasn’t anything to be disturbed about. After the war, quite a few Nazis had hidden away in the montagnes of central France, afraid of being captured. The letter assured mon oncle all efforts were being made by the authorities to handle the situation—and that was all that could be done.

Mon oncle gave a grimace when he finished translating it. “There you are, mon neveu. There is nothing to do but wait.”

A little shiver passed down through me as if a cold wind had blown up and vanished. I said, “I’d think le village would be worried.”

“It would be worried,” he replied, “if that mayor was not such a pighead and was more interested in protecting his town than in proving you and I are fools.”

There you are. As long as that Nazi remained hidden and didn’t cause any trouble, le village would go on thinking I was a muddlehead, and mon oncle was a worse muddlehead for believing me. Of course, I didn’t exactly want that Nazi to sneak down on le village at nuit and cause trouble, but—

Anyway, for a time nothing happened. It rained a lot, too. That kept us inside the hotel or the workshop. I didn’t have much of an opportunity to practice walking for a week. I helped mon oncle. While I helped I studied over in my head all that had happened to me, from Paris to St. Chamant, and it seemed to me there ought to be a means to prove to le village that up on la montagne somebody who was dangerous, armed with a pistol, was hiding.…

During that time, we rigged up the controls. We covered the wings with linen and varnished the linen until the cloth was tight as a drumhead over the ribs. I hoped mon oncle might find an opportunity to take me across the montagne where he said the Meilhacs lived. But without workmen he was too busy. He was concerned, too, I guess, more than he let on to me, because it was taking longer to build the avion than he’d expected. His money was running short. Often at nuit I’d hear him playing his flute behind the closed door of his room.

A couple of postcards arrived, signed by my father and mother. They were walking through Scotland. If I needed to reach them in an emergency, I was to have mon oncle cable the American Embassy in London; the Embassy knew how to locate them within a day or so. But there wasn’t any emergency. I decided the mayor wasn’t going to cause the trouble mon oncle had anticipated, either, about the cochon I’d accidentally shot.

Nothing happened. Nobody hummed under my window. The nuits were empty and peaceful. When I wasn’t helping mon oncle I learned French from little Philippe Graffoulier in order to write that letter to my mother. From him I learned to say, for example, “it is not.” The French are certainly peculiar. They have two words for our “not,” sticking “ne” or “n’” in front of the verb, and “pas” behind. Very queer. If I was to say, “the airplane is broken” I’d say: “L’avion est cassé.” But to say, “the airplane is not broken,” I’d have to say: “l’avion n’est pas cassé.” And, “the airplane is not going to fall” would be: “L’avion ne va pas tomber.” French can be perplexing.

On Wednesday, Suzanne Meilhac bicycled into le village to market for her mother. We had lunch together. We tried to talk to each other and laughed and I had more fun, that noon, than I imagined anybody could have with a girl. By gestures and by words she managed to make me understand that Charles was working from dawn until nuit in the vineyard in an effort to obtain a large enough crop to prevent the mayor from taking their place.

When she mentioned the mayor, she scowled. She drew down her mouth. Almost, for a second, she looked like he did. We both laughed. Madame Graffoulier had fixed a special lunch for Suzanne. Suzanne ate everything before her, as if she was tremendously hungry. When she finished, Madame Graffoulier put more vegetables in Suzanne’s basket as a gift; and Suzanne thanked her and her eyes glistened a little as if she was so pleased she was nearly ready to cry.

I tried to tell Suzanne I’d come to see them soon as I could. When she bicycled off I wished my leg was strong enough to have gone with her. After she left le village seemed suddenly lonesome and deserted.

Then, all at once, on a Friday morning, the mayor and his lawyer came into the workshop. They had a long argument with mon oncle. When they finished talking, I saw mon oncle was doing the best he could to contain his temper.

He turned to me to translate. He explained the mayor wanted 2000 francs for his dead cochon. That was nearly a hundred dollars. Mon oncle said even for a trained truffefinding pig it was an outrageous price. Before I could say a word he swung his nose around at the mayor. In a voice like a nail sliding over glass, not at all loud, but with something in it that made you shiver, he answered in French. I didn’t understand but I saw that little fat mayor’s face slowly become purple.

wanted When mon oncle had finished speaking the mayor bellowed. The mayor roared. He pointed at me. He roared some more. He said “assassin” several times, so I knew he was referring to me. Mon oncle folded his arms. He listened. He cocked his head. Almost—looking at him—you’d take him to be polite and deferential. All he said was, “Bah! Je n’ai pas peur!” which meant: “Bah! I have not fear!”

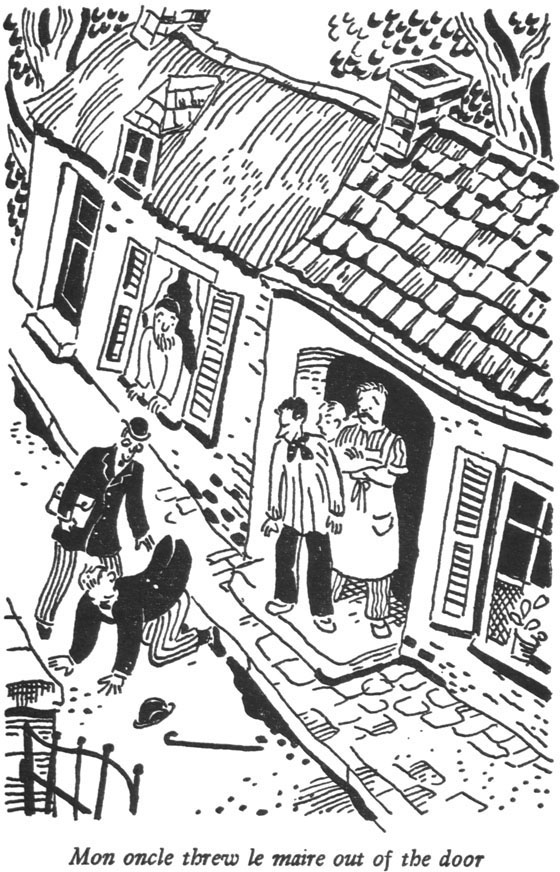

That knocked the wind out of the mayor who was trying to threaten him. The lawyer tried speaking. The mayor—le maire, as the French call it—got so angry he couldn’t wait for the lawyer to finish. He stuck out his hand and grabbed mon oncle’s nose—and then twisted it, hard!

Mon oncle became perfectly white with rage. He jumped back. Next he jumped at le maire—the mayor—and picked up le maire by the coat and seat of the pants and threw le maire out of the door. Le maire landed in that same mud ditch in which he’d landed before, with a splash which must have been heard as far away as Paris. The lawyer danced around mon oncle, saying, “Monsieur Langres! Monsieur Langres!” Mon oncle simply looked at him. The lawyer ran to the door and into la rue and helped le maire up and the two marched away, le maire shouting back the most awful sounding French threats ever to be heard. I was glad I didn’t understand them.

Mon oncle felt at his nose. He caught me eyeing him. He winked at me and tapped his big nose and calmly said, “Have no peur, Jean. My nose remains. It will take more than a Monsieur Capedulocque to detach the nose of a Langres!”

Afterwards, le forgeron tugged at his black beard and spoke to mon oncle with a grave, anxious expression on his face. Mon oncle merely laughed. I asked mon oncle what Monsieur Niort had said.

“He zinks the mayor is so angry my festival will be stopped.”

“Festival?” I asked. “Do you mean you are going to have a festival?”

They’d promised him a festival—une fête, in French—on the jour his avion flew. Le village planned to invite hundreds of people from all the towns and cities nearby and mon oncle counted on it, because he expected several rich manufacturers might be attracted, too, to see him voler. He told me, “Le village has made a promise. The mayor cannot back down on the promise.”

He began whistling, as if he’d enjoyed throwing the mayor out of the workshop. By and by le forgeron started chuckling, as if he was remembering the way the mayor had landed in the mud. Pretty soon both were laughing like two kids. In the afternoon the sun came out, bright and hot. Mon oncle told me I’d spent too much time indoors. He packed me off for the afternoon.

As an experiment I decided to see if I could walk to the lower cow field, below le village, and back. The cow field was about a mile away. I started fine. But three-quarters of the distance, my leg gave out on me. It began hurting. I reached the meadow, but I was limping. Here it was, well into the middle of the summer, and I couldn’t even go half the distance I had to go to meet the condition set by my father. I flung myself down into the grass and wondered if ever I’d be able to walk like other boys.

Le jour was beau. It was beautiful. It was fun loafing under one of the trees, the birds chirping. My leg had stopped hurting. Everything was peaceful. I could hear the faraway buzzing murmur of old Monsieur Argeau’s sawmill, east of St. Chamant. I remembered how scared I’d been the first week or so after arriving, imagining I’d seen Monsieur Simonis, imagining he’d tried to climb into my window, and thinking I’d heard Albert humming. All that was gone. It was like a bad dream. After that jaunt of mine up the montagne side with mon oncle, where I’d found the German pistol and shot the cochon—after that, except for le maire causing trouble, everything else had become peaceful and easy. I almost wished everything wasn’t quite so peaceful. If that Nazi whom I knew was up there would only scurry down here a nuit or so, things would start popping. Le village wouldn’t take so much stock in what le maire—the mayor—said every time. They’d have more belief in mon oncle.…

Upon returning, I learned from Madame Graffoulier that Suzanne Meilhac had been in town, marketing. She’d asked for me. When I saw mon oncle I asked if we might go to the Meilhac place one of these days. He said it was something he’d been planning to do. He hadn’t realized so many jours had passed since I’d last seen Charles. He promised to take time out before next week.

At evening, as the men folks trooped back into le village, I noticed they didn’t shout as good-naturedly to mon oncle as they used to. They walked by, avoiding him in the shop, scowling to themselves, whispering. Little Philippe spent about half an hour to make me comprehend what the trouble was. According to what he’d heard from his aunt, le maire had passed word around that mon oncle and I were attempting to cheat him out of the money due him for the dead cochon. You know how stories spread. He was doing his best to blacken the Langres name, never mentioning of course the huge price he’d demanded for his dead cochon.

Just before dinner, when I was upstairs in my room, le maire and his lawyer again waylaid mon oncle, asking him for the money. Afterwards, mon oncle informed me angrily they planned to lay a complaint against him and me and try to stick us in jail, because he’d refused to pay the price.

By now, I didn’t care how much le maire asked. All I wanted was to pay him. I dug out my purse in a hurry. I hadn’t used any of the money mon père had given me. I gave it all to mon oncle and his lean face flushed. He said le maire was robbing us. But, he supposed, there wasn’t anything to do except pay. He walked out of the hotel and a little later returned, glum, his pride hurt. He’d paid a hundred dollars. I had two hundred left. I hadn’t used any of it yet to pay Madame Graffoulier my bill and I wondered when she was going to hand me my account.

Perhaps Madame Graffoulier realized how mon oncle felt. Anyway, she had prepared an especially good dinner for us: potato potage, potato pancakes, fresh lentils in cheese, black bread, real cow butter, and the first meat we’d had for five or six jours.

I don’t believe I’ve ever tasted meat as good as the meat Madame Graffoulier served to us that night. Maybe I ought to explain: In France, and particularly in the part of France where I was staying, which was about the poorest and most backward section of all France, meat was something rare. Even before the war, I’ve learned, they didn’t have meat very often. Chicken and ducks, yes; but fowl wasn’t held to be meat. What we had was regular steer meat, served in long thin slices, covered with garlic sauce. That meat melted in your mouth. I noticed there were tiny black granules in it, a little larger than grains of pepper. At first, I took them to be dirt. I didn’t say anything, mainly because the meat was so good I didn’t care if Madame Graffoulier had dropped a peck of dirt in it by accident.

But the granules weren’t dirt. I happened to taste one. It was like biting into a very solid bit of mushroom. No—not a mushroom. I don’t know that I can explain. If you can imagine a tiny chunk of gelatin, about ten times firmer than gelatin should be made, not having any particular taste at first but leaving in your mouth after you’ve swallowed it a very rich taste of meat—why then, that’s what I had. I must have paused, after swallowing that black granule. I’ll admit I was surprised. The taste remained. It stayed. It filled my mouth. It became the most extraordinary and wonderful taste, fragrant and appetizing. It was as though that small particle had magically enlarged, becoming a whole mouthful of the finest steak ever cooked. I blinked.

For the first time in hours mon oncle’s face relaxed. He ceased looking as grim as he’d been looking. He asked, “Don’t you know what that is?”

I shook my head.

“Truffe!” he said. “Madame Graffoulier has cooked truffes in this meat. It is very good, I zink. Non? You see now why the mayor is so angry when you have killed his trained cochon.”

Good? That nuit when I wrote to ma mère I told her it was one of the best meals I’d had since leaving Wyoming. In my letter to mon père I wrote him I was improving and now could walk about a mile without limping too much and hoped in a year or so if he and my mother—ma mère—ever again went on another walking trip, that I might be strong enough to join them. I said I hoped they were enjoying their trip. I was writing to them steadily, nearly every nuit, even if I knew there’d be a delay in forwarding my letters to them from London.

The next jour someone had tacked up signs all through le village de St. Chamant. With an air of suppressed excitement, mon oncle translated one of them for me. The government was offering a reward of 10,000 francs to be given to anyone responsible for capturing Nazi soldiers or sympathizers supposed to be hiding in the montagnes of the Cantal. He wagged his head. “Now,” said he, “perhaps that will stir them up here in the village, if the mayor isn’t too much of a pighead.”

As we varnished the spars of the avion that morning, I kept thinking about the reward and how wonderful it would be if mon oncle or Charles Meilhac might be able to collect that reward. I asked mon oncle why he didn’t go back up to la montagne and sort of scout around? He gave me a quick grin, replying that he had more important things to do than find a Nazi. But that must have started him thinking about it.

After lunch, instead of returning to the workshop mon oncle sniffed the fresh montagne air. He stretched. He looked at me. With a kind of sheepish expression he asked if I’d like to take a ride up the montagne with him? Did I! That was like asking if I wanted to hunt ducks. Well, he ran up to his room. When he returned his coat bulged as if he’d stuck a gun in a shoulder holster hidden under his coat. I didn’t say anything. However, the thought of mon oncle meeting with a Nazi didn’t, somehow, appear too cheering. I remembered a jour or so ago I’d wished for something to happen. Now I started wishing as hard as possible that nothing would happen today.

He borrowed a bicycle for the afternoon from le forgeron, riding me on the handle-bars. He pedaled by the stone church, whistling, past the cemetery, and out by the big whitewashed tower and house belonging to le maire Capedulocque. Behind the tower and the house, surrounded by a whitewashed wall, were wooden sheds containing ducks and chickens. They clacked and gobbled at us as we went by. A donkey shoved its head over the wall and brayed. Another donkey inside Monsieur Capedulocque’s house stuck its head through a window and looked at us. A cow must have been inside, too, because a cow shoved its head out through another window.

I looked back. There in a third window was le maire himself, scowling, watching us pedal up the lane. Mon oncle glanced back. Mon oncle laughed. “Voici!” he said—meaning, “Here it is,” or “There you are.” He wagged his nose. “The donkey, the cow, and the mayor. All fit company. I zink I do not like le maire Capedulocque one little bit, non!” We followed the path we’d taken a couple of weeks ago in the oxcart. As he pedaled higher, the air became more clear. The trees were green as paint. Mon oncle stopped to rest. We picked black figs; they were sweet and juicy.

I thought we were going to la maison de ma mère. The truth is, I became a shade scared. Even though I was with mon oncle, somehow I didn’t much relish the thought of going to that high and lonesome meadow where the Nazi might be waiting. After going part way on the bicycle, we started walking. Because of my leg, mon oncle went slowly. Once, we halted in a clearing while mon oncle lit his pipe. He told me something of his plans for his avion as we rested. He said if all went well, even without workmen, he and le forgeron would have the avion ready by the middle of the month, a week or so from now. He planned soon to take it up to the meadow on ma mère’s and his land, and set up a big wooden slide for it to glide away from, over le village to the cow field on the other side. I asked if there would be as many as a hundred people at the festival. I looked forward to seeing that festival—or fête, I should say.

“A hundred?” he said. “There would be a thousand, perhaps. Two thousand.” He turned away, his face going a shade darker. “But it has been decided not to have la fête.”

“Not have it?” I cried. He didn’t answer right at once. I said, “That mayor won’t let le village have it?”

“Bah!” said mon oncle. “It is nothing. Two thousand people would be very confusing. Monsieur Capedulocque has told everyone—tout le monde—in le village that my airplane will not fly and that it would be foolish and a waste of time to march up the montagne to see it. Voilà! We do not have la fête.”

Even though he tried to hide his disappointment and joked about it, I could see it was a stunner for him. He’d counted on people coming to see him voler. It meant a lot to him. It might be a chance to sell the avion. I said, “It all goes back to me finding that German gun and shooting the cochon, doesn’t it?”

“Bah!” said mon oncle, again. “It is because the mayor is a pighead.”

I insisted, “If we could only prove someone was hiding up there, wouldn’t that help things? Wouldn’t le village realize its maire was an awful pighead?”

“Ah, perhaps today I will find the Nazi,” said mon oncle, attempting to be cheerful. “Who knows? Viens, Jean. We lose time.”

He fooled me. He didn’t take me with him to see la maison de ma mère. He swung off the path and we trudged over a hill. I thought all the time we were scouting for that Nazi. I began to be scared. My leg started aching. We crossed the other side of la montagne. We didn’t see a sign of the Nazi. But down below on the slopes, I saw a vineyard and a big stone house beyond the vineyard with noble shade trees and flowers in the sunshine. In the vineyard were two figures working. Both of them had red hair.

I let out a whoop. Right away, Charles and Suzanne dropped their hoes. They answered with French whoops. They scampered up the slope. Charles flung arms around me, kissing both cheeks, French style, jabbering away like a washing-machine motor. After him, Suzanne flung her arms around me, as if it was the most natural thing in the world for her to do. It was the first time in my life I’d been hugged by a girl. I ducked back. She only kissed one of my cheeks. As it was, probably I went red as a beet.

Mon oncle waited, smiling to himself. It was the finest surprise anybody could ask for. After greeting me, the Meilhac twins piled questions on to mon oncle. I knew they were questioning him about his avion because I heard that word repeated. Mon oncle kept on smiling, enjoying himself, and answering them. Finally, I heard Charles say, “Je veux voir l’avion, s’il vous plaît.”

I asked what he’d said.

Mon oncle replied, “You know what ‘je’ is, by now?”

I did: “Je” was “I” in French.

He explained, “‘Je veux’ is ‘I wish.’ And ‘voir’ is ‘to see.’ And you know what ‘s’il vous plaît’ is. That is ‘please,’ or ‘if you please.’”

It was like fitting a puzzle together. All at once it was simple. “Je veux voir l’avion, s’il vous plaît,” fitted together perfectly: “I wish to see the airplane, please.”

Next, mon oncle glanced at his watch. He told me he was leaving me with the Meilhac twins for a couple of hours. He’d pick me up around six o’clock. He waved, said “Au revoir,” and trotted off, covering the ground between the vineyard and the forest about ten times faster alone than when he’d come down with me.

I didn’t have time to worry over mon oncle because Charles and Suzanne kept me busy. They showed me the grapevines. In a few more weeks the grapes would be ripe. I said, “Monsieur Capedulocque—” and pointed at the vines.

Suzanne understood. She knew what I was thinking about. She clenched her fist. She frowned. She said, “Monsieur Capedulocque est un cochon!” and explained to Charles. Both of them were worried for fear the mayor would grab their vineyard this fall if the grapes didn’t sell for enough.

By and by I tried out my French. I said, “Je veux voir ta maison, s’il vous plaît.” It worked like a charm. They understood at once I’d said “I wish to see your house, please.” Their maison was down toward the bottom of the mountain, set at one end of a long meadow, with trees planted on each side of what must have been years and years ago a broad coach road. Their maison was perfectly enormous. It had two stone towers and a high peaked slate roof. Most of the windows and doors were now locked or boarded. Around the big house still showed traces of long ago gardens, rose bushes grown wild, pear trees untrimmed and shaggy.

Madame Meilhac was short and jolly, with wonderful red hair, very neat and clean. The way she acted you wouldn’t suspect she cared about being alone in a vast empty house with two children and no money any more for servants. She appeared to think it was a game, like camping out. Most of the rooms were closed off. I had glimpses of furniture covered with cloth, protected from the dust. In one long hall were rows and rows of pictures of Meilhacs, the last one smaller than the others, of a man in a modern army officer’s uniform. Charles simply said, “Mon père.” It was of his father, killed in the war.

All their misfortunes had happened after the death of their father. The Germans had robbed the bank containing the Meilhac money. The Meilhacs had been forced to sell most of their property. Now all they had was this house and the vineyard, with Madame Meilhac trying to keep that. You might have thought they’d be sorrowful. If they were, they never let on. They all were gay and cheerful. You wouldn’t ever have guessed they knew they were poor.

They treated me as if I was a visiting noble or duke. They brought out four slices of thick black bread and spread goat butter on it. Madame Meilhac opened a stone crock. She scratched in it with a wooden spoon. She managed to locate a few grains of brown sugar. She gave me most of the sugar, smiling all the while as though she had a hundred barrels more of sugar hidden away.

I felt so sorry for them I nearly choked, eating that black bread and butter with brown sugar sprinkled on it. But it was a treat for Charles and Suzanne. They licked the crumbs off their fingers. I let on it was a noble treat for me, too. I’d have rather died than have them believe I didn’t appreciate what they were doing to welcome me and to feed me in their maison.

After eating, Madame Meilhac and Suzanne cleared the table. They shoved Charles and me outside. He fetched me another bow and arrow he’d made, saying “peaurouge” a couple of times. It was going on toward late afternoon. He signified he was through working in the vines today. He meant to entertain me; I was his guest. He thought I’d enjoy playing Indian. Well, it struck me funny to play Indian thousands of miles away from home. We crawled up to the vineyard. Charles and I shot his arrow at the vines and whooped and did our best to pretend we were wild Indians—but somehow it didn’t go over.

By and by, without saying anything, we simply stopped playing. Both of us were melancholy. I could imagine Charles thinking about his vines, worrying, hoping le maire Capedulocque wouldn’t take them away this fall. It seemed to me le maire must be the greediest man alive, or the meanest. He was after my mother’s and my uncle’s property up higher in the montagnes, even though there weren’t any vineyards there—and he was after the Meilhacs’, down here. You’d think it was more than just grabbing land. It was as though he was determined to rid le village for good of both the Meilhac family and anyone belonging to the Langres family. I couldn’t understand such hatred. In some respects he was worse than Monsieur Simonis had been—meaner, too.

Once more I got to thinking about le maire, wondering if there wasn’t any way to make le village appreciate what a pighead he was. You know how it is when you moon along, idly, thinking about something, almost dreaming what could happen in your head?

Well, all at once, it appeared to me I’d stumbled upon a solution. I knew exactly how to wake up the entire village to the danger that Nazi was to them. I had discovered a way to excite them and worry them and send them tramping through those montagnes until there wasn’t an inch left for a man to try to hide himself in!