After Pearl finally arrived, the Stationer circuit had approximately 20 members who were headed by an SOE-trained group of four: Maurice Southgate, leader/organizer; Amédée Maingard, radio operator and assistant organizer; Jacqueline Nearne, a courier who parachuted in with Maurice in January 1943; and Pearl.

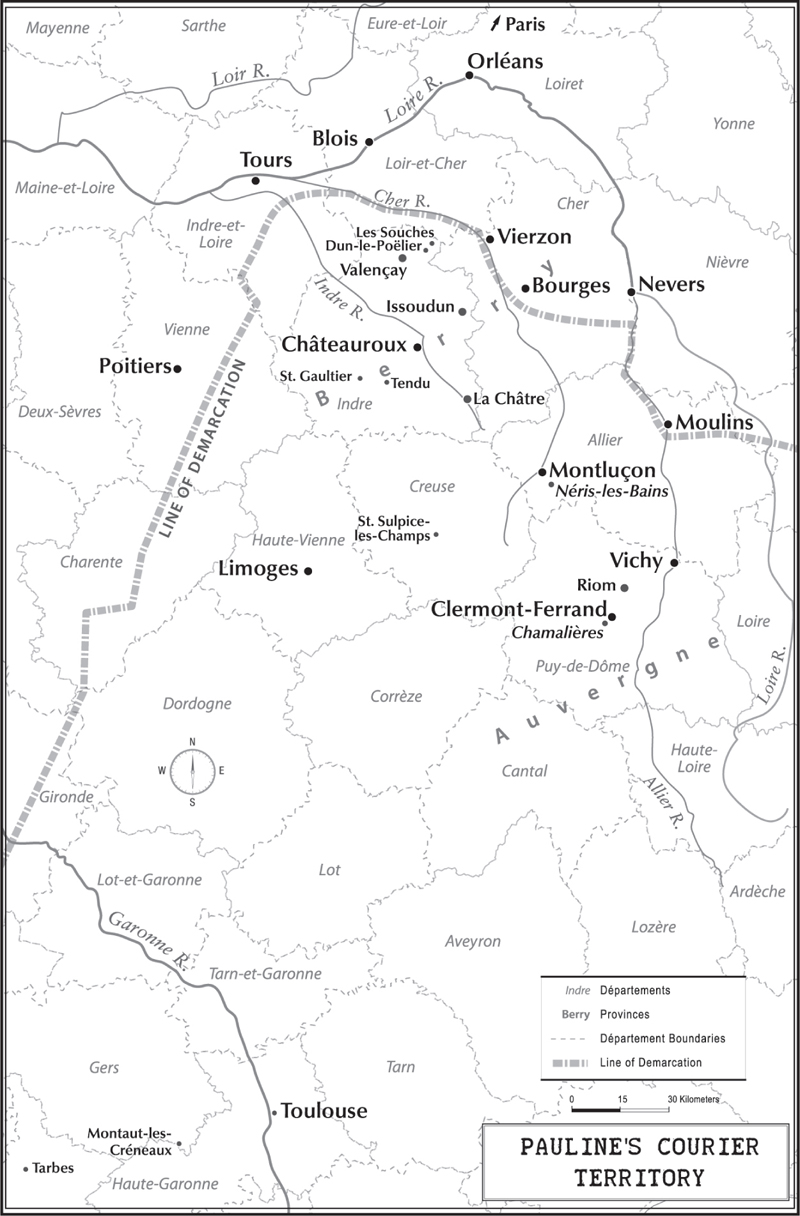

The area covered by Stationer was large partly because it worked closely and cooperated—liaised—with several nearby Resistance networks. Sometimes Pearl’s courier work overlapped with liaison work with these networks on behalf of Stationer. The Stationer network had liaised most closely with the Headmaster network, and a few months before Pearl’s arrival, Headmaster’s leaders had been arrested. Stationer filled in the gap, making the work of the already large network even larger and the trips for its couriers longer. By the time Pearl landed in France, Stationer was assisting Headmaster’s Maquis groups under the leadership of Henri Ingrand in Auvergne and Jacques Dufour (code named “Anastasie”) in the Dordogne region, near Limoges.

Because they worked out in the open, couriers were greatly at risk for capture, interrogation, and death if they were found with Resistance materials. This is why many couriers, Pearl included, tried to memorize their information when they could. But sometimes it was not possible to memorize everything: although addresses, messages, and even timetables for parachute drops and agent pickups could be memorized, sometimes couriers had to transport more complex items such as grid references, maps, or items that couldn’t fit into a pocket.

Although all SOE agents entering occupied countries acquired new identities—including a new name, a new personal history, and a pretense of new employment—that they had to memorize until the details were second nature, couriers perhaps had an especial need of them since they were constantly out in public.

I worked as a courier under Maurice Southgate for seven months. He was incredibly security minded. He was so strict about security that when he sent me somewhere, he never explained the whys and wherefores. He never used one word more than was necessary. He would tell me where to go, who to see, and what to say, and I never tried to find out more. If I had been arrested and interrogated, I had absolutely no background information about my work and, except occasionally, I didn’t need any.

For instance, when I asked him where I had landed he replied, “Luant,” but it wasn’t Luant at all, it was Tendu. I discovered that much later. He said this most likely to protect Monsieur Chantraine, who owned the land where I parachuted.

One day Maurice said to me, “Go to Poitiers, we haven’t had any news from … “ and he gave the name of someone I didn’t know. “Go to the bursar’s office at this address. You don’t need to speak to anyone, go past the desk and straight to the first floor.”

I left Montluçon for Poitiers. I must have arrived in the morning because I was there all day. Well, I got to the address, went in, and was walking past the concierge who was talking to someone at the desk when he asked, “Where are you going, Madame?”

“I’m going to the bursar’s office.”

“Get out of here,” he whispered, “the Gestapo’s here!”

“Maybe, but we haven’t any news from … I’d like some news—”

“I’ve told you, get out!”

That was a close shave! If the concierge hadn’t been there, I’d have walked straight into the trap.

I didn’t get the information I went there for—the only time that happened—and the other minor problem was there were no return trains before the evening. I had to spend all day there and didn’t know anybody. In fact, it’s the only day when I could be a tourist. I must have visited every church in Poitiers, and there are plenty of them!

I always memorized my messages; I never, ever had anything written down. But one day, this got me into a real mess. Maurice told me to see Madame Cochet in Chamalières. She was General [Gabriel] Cochet’s wife, the former chief of staff of the French Air Force who was in England with de Gaulle. She was to be flown to England in a Lysander [a small aircraft especially used for clandestine missions during World War II]. Maurice told me her address and I thought I had remembered it.

When I arrived in Clermont-Ferrand there was a curfew. I waited until the curfew was over before leaving the station, but unfortunately there was a tramway strike. I had to walk all the way to Chamalières [a mile away]. When I got there, I went to what I thought was the right address. I knocked on the door: “I would like to see Madame Cochet, please.” A rather sleepy man answered, “Don’t know her.”

“But she’s expecting me.

“No, she’s not here.”

Then he asked something that made me think he was in the Resistance as well: “Who sent you?”

“Geneviève.”

“No. Not here.”

I wandered down the street thinking, It’s impossible, I’m sure it’s the right house.

In fact I had got it completely wrong! I thought that I had totally messed up the mission. I didn’t know what to do. In desperation, I went to sit on a bench, still thinking, What am I going to do?

Suddenly, I saw Madame Cochet leave the hairdresser’s, just on the other side of the street! She lived at the beginning of the street while I remembered a number at the end; I’ve no idea why. I was so relieved. This incident taught me never to forget anything.

This is another example of a mission, one I did with Jacques Hirsch, a Jewish member of the Resistance. I could never have managed to do it alone. We had to transport a direction-finding device for pilots. It was packed into two enormous suitcases and was to be set up in a chimney in a farmhouse. The farmer was supposed to operate the device after hearing a special message on the BBC. It helped pilots find their way when they were flying south.

Jacques Hirsch first had to find the farm and find someone who was willing to do the work—night work. The equipment was dropped by parachute miles away from the farm Jacques had found. Then we took care of transporting it to its destination, always traveling by train. We took a great risk that policemen or soldiers might demand to look inside the cases.

All Jacques’s family was involved in the Resistance. They had a daughter and two sons—Pierre, who was Maurice’s second radio operator, and Jacques, with whom I often worked during the clandestine period. The girl was also in the network; she was an occasional courier for Maurice.

An apartment rented by Jacques’s parents in Toulouse was my base when I was there. His parents ran a ready-to-wear clothes shop in Paris. They took refuge in a small village called Saint-Sulpice-les-Champs. Sometimes we also stayed there. They also lent us money. Maurice would have a prearranged message broadcast by the BBC, which guaranteed they would be reimbursed after the war.

Jacques was an incredibly anxious man. I always admired him for his bravery, because his fear didn’t stop him doing the job. To start with, he was rejected by the army because he was Jewish, then he went to study Roman law at Toulouse University. In his final exam he got 19.5 out of 20. He had an extraordinary memory; he read the train timetables so many times for our work that he knew the official railway timetable by heart.

One day Maurice said to me, “Some parachutists have just arrived. They have money for the network; go and collect it. Go to La Châtre. There’s no password; we don’t know anybody there and nobody knows you. Just in case there’s a problem, you can say that Robert sent you. Sort it out.”

I arrived at the address he had given me in La Châtre—it was a grocer’s shop and bistro. There was a lady behind the counter. I said, “Good morning, is Monsieur Langlois in?”

“No, my husband’s away today.”

“I really need to see him. Money has arrived on behalf of Robert. I’ve come to collect it for our network.”

“Well he’s not here. I don’t know anything about it.”

“Can I come back later?”

“You can come back tomorrow.”

“No, I can’t come back tomorrow because I have to come by train from Montluçon.”

There were only three trains a week, so I couldn’t return until the day after.

Two days later, I returned to La Châtre from Montluçon. When I entered the bistro, I saw Madame Langlois’s expression and thought, Oh dear, I’m in for trouble. I sensed it immediately.

A man whom I had never seen before entered through a side door. He said, “Good morning, Madame.”

“Good morning, Monsieur.”

“I’m Robert. I don’t know you.”

“Indeed, well I don’t know you either.”

“Follow me.”

He led me up a spiral staircase into a room where I noticed a door ajar. He asked me to sit down and started interrogating me. We didn’t work for the same network, so he didn’t know any of the people I knew and vice versa. After a number of other questions I could not answer, I started to panic. Deep down I was wondering what on earth I was going to do. I didn’t want to play my trump card for the sake of the network’s security. Finally, when all other attempts had failed, I said, “Do you know Octave?”

“No.”

“Octave is Monsieur Chantraine!”

“Ah, yes.”

“I was parachuted to his farm on September 23.”

At that moment, four or five chaps came out of the next room. Robert was convinced that I was in Pétain’s militia, the Milice [the Milice Française, or French militia, that worked for Vichy France and against the Resistance], and to avoid putting his men at risk, he had everything prepared to pop me off. He wrote about this incident in a magazine published on the Resistance immediately after the war. The magazine was edited in Châteauroux and called The Bazooka. He wrote an article explaining that he had planned to strangle me. If I had not managed to convince him with the last name, I don’t know how I would have got out of it—I really don’t know how. If I hadn’t known Chantraine … Being killed by another resister, that would have been the end!

I had no personal means of transport, but I used something very practical—an annual rail card. Maurice discovered that it was valid for the set routes we needed to use. It was quite expensive but worthwhile because there were many travelers, very few trains, and long queues [lines] at the ticket offices. You even needed a special ticket for some trains. With the annual rail card you didn’t queue and you could get on the trains reserved for travelers with the pass.

I usually traveled at night so I didn’t get much sleep, but there weren’t as many controls then. For long journeys, such as the one I did quite frequently from Toulouse to Riom, I left at 7 PM and didn’t arrive until 11 AM the next morning. Sometimes I would take a “couchette,” but only for part of the journey because I had to change trains. I was very surprised when I first used a couchette because men and women were mixed up together in the same compartment. There were four couchettes in a compartment; we slept on the top or the bottom bunk. And this was first class, the way I always traveled.

When I took the train I always had a collection of pro-German magazines in French. There was one called Signal, another Carrefour—that kind of magazine. Only one person ever spoke to me, because I didn’t look French. I looked German, especially as I did my hair in the German style, in a plait around my head.

When I was on the move, I had nowhere to cook and I didn’t eat in small bistros but in restaurants that obtained their food from the black market. They were all over France and anyone could go if you had the right introduction—but it was also dangerous, for you never knew who would be inside.

When I was in Clermont-Ferrand I ate at the Brasserie de Strasbourg where all the extras were black market-supplied. Food in France was scarce, but we agents were always supplied with enough money to live—and eat—decently. The French gendarmerie [regular French police] controlled the black market. Some were accomplices and closed their eyes to certain things. However, when they went to Gare Montparnasse in Paris, to control the black market, that was another story! These gendarmes would seize black market products for themselves.

A lot of people went to Villedieu-les-Poêles in Normandy to get food. It was obvious what the travelers getting off the trains were up to. They all had such big suitcases they had to drag them along—you could almost see the blood from the meat dripping out. An enormous number of gendarmes would wait for these trains from Normandy. They would let two or three people go by; then they would stop one. They would ask what was in the case and the people had no choice, they had to open it. So they were fined and the goods were confiscated.

My false identity when I was working for Maurice was Marie Jeanne Marthe Vergès, who was someone else’s real identity. Jacques Hirsch had taken me to a village called Montaut-les-Créneaux. The local mayor showed me the births and deaths register and told me to choose a name. Marie Jeanne Marthe Vergès was slightly older than me. She had completely disappeared. It was a real identity, but nobody knew what had happened to the girl.

My cover was this: I was posing as a representative for Isabelle Lancray, a cosmetics firm that my future father-in-law had established with a partner. I had official papers and everything I needed. I don’t need to add that I didn’t have time to do much selling! The cover story was mainly for all the traveling and identity controls. You had to be able to answer the first basic questions. It also helped me to rent the room in Montluçon. I left publicity brochures in the room and the landlady saw me coming and going at completely irregular hours but she thought I was a representative.

On only one occasion did I have the impression that someone suspected that I was not really a cosmetics representative. It was just before D-day, during my last train journey from Montluçon to Paris. The journey had been an absolute nightmare because on top of the usual problems, many train lines had been blown up. I had spent all night changing trains. Toward the end of the journey, when we were near Paris, I was sitting on top of the toilet in the water closet as there was nowhere else to sit. I was sleepy, the train was overcrowded; it was dreadful. A man had been watching me for quite a while and without warning he said, “What do you do for a living?”

“I’m a representative for beauty products.”

“Well it doesn’t look like it; you’re not wearing any makeup this morning.”

“Do you think I feel like putting makeup on after the night I’ve just spent?”

I’m sure he suspected something strange about me. But I actually never wore any makeup and, apart from that one incident, I was never questioned about it.

Until D-day, we didn’t need the whole French population with us, if only for security reasons. The smaller and tighter the network, the better. Ours covered a territory which, in my opinion, was far too wide [between Paris, Vierzon, Châteauroux, Montluçon, Clermont-Ferrand, Limoges, Toulouse, Tarbes, and Poitiers.]

Our liaison missions forced us to be continually on the move. It took a huge amount of time. I have no idea what Jacqueline Nearne did; she arrived before me and was Maurice’s other courier. I have absolutely no idea, even though she was there for over a year.

Our work consisted of forming small groups all over the place, so that on D-day the groups could expand and help the Allies. That’s what happened in the north of Indre and the Cher valley.