After the arrest of Maurice Southgate, Stationer’s radio operator and assistant organizer, Amédée Maingard, and Pearl split the enormous Stationer network into three sections. Pearl took the northern part of the Indre department, which she renamed Marie-Wrestler circuit after two of her code names. It is believed that, at this point in time, Pearl’s image was placed on German “wanted” posters (see note on page 167) in the Montluçon area with a large monetary award offered for her arrest.

While initiating her second wave of Resistance work immediately following the Battle of Les Souches, Pearl stayed with the Trochet family, Monsieur and Madame Henri Trochet—whom Pearl affectionately referred to as Grandpa and Grandma Trochet—and their son. Then, while still taking her meals with the Trochets, she lived in the woods with Henri—who worked under Pearl as her second in command—and the men of the Maquis, who knew her by the code name “Pauline” (the name of one of Pearl’s childhood dolls). Immediately after D-day, realizing that the Allies now had a good chance of winning the war, there was a flood of volunteers who joined whatever Maquis groups they could find—especially those with leaders who could, like Pearl, keep them supplied with weapons.

Although during training in London Pearl had expressed alarm at the idea of liaising with a leader who controlled a 1,000-strong Maquis group, she soon became the leader of an even larger group herself. Shortly after D-day, the Marie-Wrestler circuit prevented numerous German troops and munitions from reaching the Normandy coast by staging constant acts of railroad sabotage. At one point, Pearl passed on to London information that led to the RAF bombing of a German train of 60 tanks of gasoline that had been headed for Normandy. The destruction of the tanks delayed numerous German troops from reaching the coast.

From June 12, we stayed at Doulçay, a farm near Maray, with Monsieur and Madame Henri Trochet and their son André. Madame Trochet cooked and we had a room overlooking the back of the farm. Farms had rather rudimentary comfort in those days: you had to use a pitcher to wash and there was no loo [toilet]. When we had nothing to do we helped Monsieur Trochet harvest crops because it was summer. But we were not very good at it; we were very amateurish farmers.

Grandma Trochet hardly ever talked and was always very gentle, but she knew exactly what she was up to. She managed the farm with skill and without making a fuss about it. But Monsieur Trochet had a very strong personality. He was a typical man of Berry. He had an enormous moustache and always had a hat screwed onto his head. Maybe he had a cold tummy because he always wore a cummerbund over his trousers. He loved hunting and fishing, so it was actually his wife, Madame Trochet, who worked the farm. She took care of the animals and everything to do with the house. Grandpa Trochet did all the heavy work outside. They had 250 acres in all, some crops, some woodland, there was a large vegetable garden, about 20 cows, goats, chickens, and Muscovy ducks.

One day his car wouldn’t start so Monsieur Trochet took me to Mennetou station with the neighbor’s horse and cart. And you don’t have to believe me, but the horse stopped all on his own in front of the bistro before reaching the station. When I asked Grandpa Trochet if he was going to visit us in Paris, he didn’t want to. He replied “I’m not goin’ there, you’se only drink water.”

He didn’t even use much water to wash himself—it was done so quickly. One day he had something wrong with his teeth, I don’t know what. There was a dentist in the Maquis, he broke a drill on Grandpa’s teeth they were so hard. He used a finger to brush his teeth, once to the right, once to the left—all brushed. It was the same for everything he did. All right, I’ll wash, but is it really necessary?

He had an amazing sense of humor and a sensational way of telling stories with his accent. I can’t imitate him. He also cheated a bit at cards. One day I saw his wife playing with him. I whispered to her, “Be careful when you play, he cheats.” She replied, “Yes, me too, but he doesn’t know it.” They were an amazing couple.

The Battle of Les Souches left us in a hopeless state—we had nothing left, no weapons and no radio. The Krauts had pinched everything except the money I had hidden under my bed in a cocoa tin. I managed to take it with me when we were attacked. If I remember rightly we had about 500,000 francs [see note on page 168]. In any case it was a large amount because it lasted for a long time. Because we had no radio, the only way I could contact London for more supplies to be parachuted was by going to Saint-Viâtre on the other side of the demarcation line across the Cher River, to meet Philippe de Vomécourt [known by his SOE code name, “Saint Paul”], who could send a message via radio.

Pierre Chassagne, a former member of the Adolphe subnetwork, knew where I could find someone in Saint-Viâtre who could help me get in touch with Saint Paul. Around June 14, Pierre came to Doulçay and we cycled north to Saint-Loup to cross the Cher. I took off my shoes, carried my bike on my shoulders, and waded across over some damned sharp stones.

Shortly after we had arrived in Saint-Viâtre we decided it was time to have lunch. We stopped on a bank along the side of the road to eat our sandwiches—Madame Trochet must have made them. Then I noticed a front-wheel-drive vehicle coming from the left toward us; the engine made a very characteristic, familiar noise. I recognized the registration number; it was Monsieur Hay des Nétumières’s car with Germans inside. I said to Chassagne, “Now it’s Saint Paul’s turn to be attacked.”

He left me sitting on the bank and went into Saint-Viâtre to make contact. When he reached his contact, he was told the Germans had come to attack Saint Paul’s Maquis. But the Maquis had dispersed just in time. The car we had seen was probably carrying officers leading the way for the trucks of soldiers. But our trip to Saint-Viâtre was a waste of time because I still had no way of contacting London.

Two days later, Chassagne came to me and said, “I’ll go alone, give me the message.” I gave him the message, which he hid in the bike’s saddle support. After Saint Paul had received it, he came to visit me in Doulçay disguised, as usual, as a gamekeeper. He said Germans always respected uniforms. And he was so well disguised that I didn’t recognize him at first!

He had transmitted my message to London, and on June 24 we received a large parachute drop on a piece of land we called “whale”—all our landing sites had the names of fish or marine animals. The equipment was parachuted next to Grandmont farm, near the Trochets, on Monsieur Hennequart’s land. Three planes were used to carry the supplies—we needed to be completely rearmed.

We received hand grenades, Stens [machine guns], plastic explosives, and so on. Usually when drops were taking place, there weren’t many people around for security reasons—we had to avoid going to and fro across the countryside. But this drop was an exception. It was our first big drop after D-day and we spent two days and one night just distributing arms to the Maquis leaders in our sector. I didn’t even have time to wash during those two days.

When we were re-equipped we contacted or recontacted everyone willing to help us—in Genouilly, Vatan, Graçay, Dun-le-Poëlier. I often met Alex, the local FTP leader, and spent nearly all my time liaising with the different resistance groups.

Immediately after the Battle of Le Souches we had 20 Maquis at most working with the Stationer network. Now volunteers came flooding in: locals, boys from youth camps, and a few who had been commandeered for the STO [Service du travail obligatoire, the compulsory work service, still operating in 1944] who didn’t want to go to Germany and so joined the Maquis.

The men’s motivation was to chuck the Germans out. Full stop. Very few of them were married; they were mainly youngsters who were old enough to do their military service. These boys didn’t want to join the Communist Maquis, so they came to us. They had learned that we could supply arms.

Within a very short time there were at least 150 of us, and soon after that there were about 1,500. At the end we had about 3,500 men. You can’t imagine how much humility I learned from those men. We were dealing with the most down-to-earth farm workers, but there was also an intellectual elite.

One day I said to Henri, “We can’t carry on like this; a large group such as this needs to be organized.” So we divided them into four Maquis groups: each one had a leader and its own territory. It was an exceptional situation because I, who had worked as a courier, organized them and had the idea of dividing the Nord-Indre Maquis [north Indre, the Marie-Wrestler network] into four subsections.

The first subsection was led by “Comte” [Roland Pérot]; the second by “Parrain” [real name not known] at first, then by “Robert” [Camille Boiziau]; the third by Georges Prieur then by “Emile” [Emile Goumain]; and the fourth by “La Lingerie” [Paul Vannier]—we gave him this name because had an underwear manufacturing business in Reuilly.

The main thing was to stop the Maquis from becoming a completely disorganized shambles. I was in charge, but it was not easy for me because I hadn’t been trained for this role. In practice the four subdivisions operated very well and were well supplied. In all, 150 tons of arms were parachuted by 60 planes. The Amicale [group of former resisters from the Norde-Indre and Cher Valley Maquis] still consider me as their leader but only because I was in a very special position when the four sections were formed. In other words, we started organizing these Maquis, we had set it up.

But finally, on July 25, after I had asked repeatedly for a military commander, to my great relief one arrived. He was an army captain called Francis Perdriset. Until then Perdriset and his wife and daughter lived in Châteauroux [the capital of Indre, where the regional leaders of the AS and the FFI had secret headquarters]. He worked near Le Blanc for the Resistance and had been a Maquis instructor long before D-Day.

But when he came to us he wanted to allocate ranks to the maquisards: sergeant, adjutant, and so on. He was an officer in the French army and immediately wanted to organize us as such. I said, “Look, they’re all volunteers. I’m not sure it’s a good idea giving them ranks as if they were in an army. There are four subsectors, each with a leader. It’s up to each leader to decide how to organize his Maquis.”

We couldn’t act as an army: get up at a fixed time, do a certain thing, clean the courtyard. Absolutely nothing could be planned in advance. However, we continued to cooperate with Francis, and he didn’t change the organization of the four Maquis groups. Each military commander gave instructions to the men. I don’t know exactly what they did as I was never mixed up in this. The Maquis role was to harass German troops; they fought the Germans who were passing through the area. There were at least four, five, or six battles—or rather skirmishes—with the Germans. I don’t know exactly how many. That was their job, not mine. I let them get on with it; they didn’t report to me.

I was in touch with London via our radio operator, requesting arms and money for all the Maquis groups we now regularly visited. I did what I could to keep them all supplied while ensuring we didn’t order too many, but though I had this key position I tried to keep a low profile. One of the maquisards wrote a poem and called me “L’Arlésienne” of the Maquis because I could never be seen [L’Arlésienne is the name of a famous French play where the title character never appears]. One thing that really makes my blood boil is hearing people say, “She was in the war, bang-bang-bang, she blew up trains and all sorts …” It’s just not true. All I did was to visit and arm the resisters.

The D-day landing was the turning point in our work. For a start, there was no more Gestapo, at least in the region where I was based at the time—the north of Indre and the Cher Valley. The Gestapo and the German army were two completely different things. Secondly, open warfare began. We could fight. It was the period when the Maquis had to prevent the Germans first getting to Normandy and after that, from returning to Germany.

As far as I was concerned working with the Maquis after D-Day was much less tiring and stressful than the clandestine period, when I was working as a courier. I could never have been a spy; it’s not in my nature at all! Although I needed a false identity and a false profession, the false cover just enabled me to do my job. To be a secret agent is to be someone else and to have to look for information, sometimes in a completely dishonest way. That’s something I’m not comfortable with—acting and doing things on the sly.

I held the purse strings with Henri and Monsieur Gaëtan Ravineau [a member of the Maquis who later became chief treasurer and paymaster]; London didn’t send me much money in the beginning, I suspect because I was a woman. Because I was asking for lots of arms at this point they must have deducted that I had a fair-sized team with me, so they sent more money. Some of the lads who joined our Maquis had families to care for, so we had to give them something. Francis Perdriset decided to give them, I think, 20 francs a day each, which wasn’t bad in those days. Twenty francs a day for almost two months made quite a tidy sum at the end. The men had to eat, so they had to find a cook, buy food, and so on. Quite a lot of farms supplied food. When necessary, the Maquis requisitioned things: food, bicycles, money, or provisions in exchange for vouchers, which were to be reimbursed after the war.

I had a good relationship with everyone with whom I worked. We were friendly and I never argued with anyone. But then again no one ever questioned what I said—only Alex. I never argued with him, either, but he did his own thing. We were submerged by all the chaps joining us who didn’t want to work with him. He was very political; his FTP all wore uniforms with a red star that identified them as Communists.

The first time Philippe de Vomécourt [“Saint Paul”] came to see us in Maray by bicycle, I asked him to visit Alex with me to try and persuade him to remove the stars because if they were captured by the Germans wearing those uniforms, they wouldn’t have any chance of coming out alive. It was my caring streak; it was completely idiotic putting human lives at risk out of sheer pride. Philippe de Vomécourt accompanied me to Alex’s tent, but it was all in vain. But though the FTP were often in conflict with the Germans, they were never arrested.

His group did their job: guerilla war, destroying railway tracks. Whatever I tried to discuss, all he wanted were arms, arms, and more arms. That’s the way it went. I knew I wouldn’t be able to do anything with him, but he was in the middle of our sector; we had to put up with him. He had a lot of respect for me, I’m sure of it, but that’s all. He never left his tent. He was in the woods and if he needed to see me I had to go to him. He and I also exchanged letters daily. His messenger dropped them in a tree trunk hole. Henri or I went to collect the messages and at the same time left one for him. They were put in a bicycle tire inner tube to protect them from the rain.

Francis [Perdriset] came to live with us in Doulçay, as did Mercier, his assistant who was a lieutenant in the French Air Force. At the time we decided to sleep in the woods. There was a little wood nearby and we set up tents made out of nylon parachutes. To set up the first tent, we attached the top of a parachute to a branch and spread out the cloth. It wasn’t bad until it rained, when we realized the inside was full of steam. The drops of water transformed into a sort of drizzle. I said to Henri, “This isn’t very practical; we’ll have to put a second parachute over the first, with a gap of about six inches. Maybe the drops will run down the inner one.”

We tried it and it worked. We also put up a parachute-tent for Francis and his assistant, one for an office—they had a type-writer—and one for visitors who couldn’t make it back to their base. We slept on the ground, on straw supplied by Monsieur Trochet in sleeping bags of a kind, made with more parachutes. We were there until we went to the Gâtines Forest.

Sometimes I’m asked if being surrounded by so many men was difficult for me, but I never had any trouble, or problems with them, never. The men called me “our mother” and they still do. At that time I wasn’t old enough to be their mother—I was 29, whereas most of them were about 20—but I was indeed older than them. I suppose they looked on me as an older sister. Also, I had come to help them although I wasn’t French; that had something to do with the way they treated me. And everyone knew that Henri and I were together. They always respected us. The first time Grandpa Trochet saw us, he thought, Those two look like they’re well and truly together.

During this time girls were often used as couriers. For example Anne and Monique Bled, some couriers I knew, would sometimes cycle all the way from Blois to Valençay. Monique even told me not so long ago that she made that 30-mile trip nearly every day. That takes some cycling. They probably needed weapons near Blois as well, maybe some weapons were sent there. But I do know she came with messages, to see Boiziau, I think. It was all for the benefit of their father, Monsieur Bled, who was in an FTP Maquis near Blois.

As much as possible, she didn’t carry written messages. Sometimes, however, she slipped them into the handlebars of her bike or into the satchel, using the paper to wrap up some item or other. But that was rare. She wasn’t yet 17 when she told her father she wanted to do this. He would not accept it. Then one day, at the end of December 1943, she said to him, “Listen, you say that we are little girls, but who would be suspicious of little girls? On the contrary, that might be very useful?”

The idea had its way—nobody ever suspected them. One time, though, the Germans stopped her because they wanted her bike. One of them chased her onto a side road, and she said she never had so much courage for pedaling! You understand, he had a grenade in his hand. That reassured her, because she said to herself, If he throws the grenade, he kills the girl, but he doesn’t get the bike. You see the little things one depends on! Later she went through some sticky patches and her family was nearly arrested by the Gestapo. She had the same sort of problems as I did with the resistance.

On August 4, when we were still at the Doulçay farm with the Trochets, Comte, who led one of the Maquis, came to find us at the farm to tell us that the evening before he had received a parachuted Jedburgh mission team. Jedburgh teams were composed of three men, including one Frenchman, and were parachuted behind enemy lines after D-day to help groups needing to liaise with England. They were also meant to coordinate the Maquis’ actions in order to back the Allies.

When Comte told me about this mission, I said, “What? I don’t know anything about this.”

“That’s why I came to tell you, but we don’t know what to do with them. And the three of them are in uniform.”

“I must see them because I don’t understand what is going on at all.”

The next day or the day after, Major A. H. Clutton, an Englishman, arrived at the farm. He was a middle-aged man who had fought at Verdun during the First World War. He was parachuted on August 4 near Vatan along with an English radio operator called T. S. “James” Menzies and a Frenchman called J. Vermot, his assistant, whose code name was “Brouillard” [fog]. I don’t know why they decided to send this tall chap in uniform; it was dangerous because there were still Germans about. Anyway I introduced myself by saying, “What are you doing here?”

“And what about yourself?” he replied.

“I’m afraid I’ve been here quite a while. I’m SOE, I was parachuted in; we have four Maquis groups here.”

That’s how we met each other.

Pearl (far right) and her sisters with Lucy, a World War I Belgian refugee who lived for a time with the family, circa 1919.

Pearl, circa 1926.

Pearl (first row, fifth from left) with her troop of Girl Guides (English Girl Scouts), circa 1924.

Pearl (far left) with her mother and sisters, circa 1927.

Pearl and her sisters, all dressed in their WAAF uniforms, before Pearl left for France in 1943.

Pearl, circa 1932.

Pearl in her WAAF uniform before she left for France in 1943.

Henri (standing, fourth from left) with several of the other French POWs at Steinfel D Stalag XII B, May 1941. A German guard on the far right.

Pearl, circa 1944.

Pearl’s railway pass that she used while working as a courier and that identified her as Marie Vergès.

Pearl’s false birth certificate.

Henri’s false ID card identifying him as Jean Gauthier, a farmer.

Les Souches château after the war, as the Germans left it. They returned to the area two days after the Battle of Les Souches and burned much of the estate, including the château.

In Valençay, 1944, after France was liberated. Left to right: the Duke of Valençay (who owned the château where Pearl and Henri stayed when the Maquis were in the Gâtines Forest), Princesse Radziwill, Pearl, Francis Perdriset.

With Captain Francis Perdriset leading, Pearl marches in the Liberation of Valençay, France, with the Maquis, September 24, 1944. To her left is Major A. J. Clutton, head of the Jedburgh Team, and to her right is his assistant, J. Vermot (“Broullard”). Courtesy of Daniel Boutineau

Group of resisters in 1944 after France was liberated. Left to right: Jimmy Menzies (the radio operator for the Jedburgh team), Robert Knéper, Henri Cornioley, Francis Perdriset, Roland Perot (“Comte”), Pearl.

Pearl in 1944.

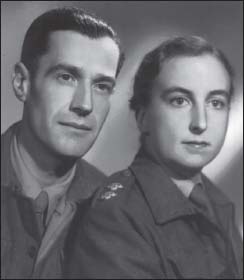

Pearl in 1945.

Henri in 1945.

Pearl and Henri in 1944.

Pearl in New York during the American lecture tour, February 1946. She’s pointing to the Marie-Wrestler section of the Stationer network on a map.

Pearl and Henri at the inauguration of a Resistance memorial (the Bruneval Memorial), circa 1947.

Left to right: Pearl; Maurice Buckmaster, head of the SOE’s F Section; and Yvonne Cormeau, another agent of the F Section, several decades after the war. They are standing in front of Wanborough Manor, one of the places where SOE agents trained.

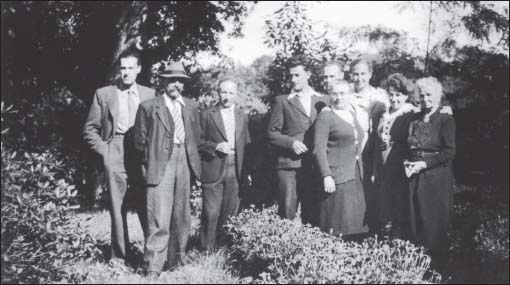

At the Trochets’ farm near Maray sometime after the war. Henri is on the far left. “Grandpa” Trochet is standing next to Henri wearing a hat. André Trochet, their son, is wearing an open shirt and is standing next to his mother, “Grandma” Trochet. Pearl is standing behind and to the right of Grandma Trochet. Everyone else in the photo is unidentified.

Pearl when Hervé Larroque interviewed her in 1995.

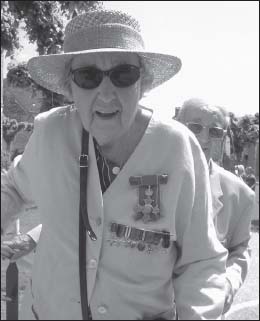

Pearl during a ceremony in Levroux (Indre), France, May 20, 2004.

Pearl and other former SOE agents standing in front of the SOE memorial in Valençay, France, during a ceremony honoring SOE agents, May 6, 2005. Left to right: Henri Diacono, Jacques Poirier, Pearl, Bob Malouboer.

Pearl with Queen Elizabeth II at the British Embassy in Paris, April 2004, after the queen had awarded Pearl with the CBE (Commander of the British Empire) “for services to UK French relations and to the history of the Second World War.” Upon presenting the award to Pearl, the queen said, “You’ve waited a long time for this.”