CHAPTER 2

THE HEIRLOOM VEGETABLE TODAY

There have always been seed savers of one sort or another in this country. One of the most well known in recent times was John Withee in Massachusetts, who during the 1970s established the Wanigan Associates Collection, assembled from some four hundred collectors, of old-fashioned bean varieties. Withee was inspired by a passion for beans and by a fear that many of his old-time favorites would disappear. His collection of more than 1,100 bean varieties is now housed at Heritage Farm in Decorah, Iowa, and maintained by Seed Savers Exchange.

Unfortunately, individuals with Withee’s foresight and energy have been the exception rather than the rule. The conscious effort to organize this type of conservation gardening into a unified purpose outside government-funded projects has occurred only within the past forty years, although there have been pioneering efforts that date back a century. The most famous of these is the Vavilov Institute, established in 1895 at Saint Petersburg, Russia. It is named after one of its most famous plant geneticists, Nikolai I. Vavilov (1887–1943).

Vavilov was interested in the preservation of genetic diversity, and his work with heirloom plants in this area has greatly influenced the thinking of all groups involved in the heirloom seed movement. Vavilov focused on the genetic diversity of agricultural crops and their wild relatives. Seeds were gathered and stored in scientifically controlled environments called gene banks. This was augmented by botanical gardens that maintained nonconsumable plants.

Genetic diversity is the slight genetic variation that appears in “open-pollinated” plants, those pollinated by natural means such as insects, rain, dew, or wind. Genetic diversity may express itself in varying shades of green in the leaf coloring of a certain cabbage variety, or in the shape of different tomatoes on the same plant. Sometimes it expresses itself in unseen traits, such as resistance to virus or, in corn, with higher starch content in the dry seed. Genetic diversity is what ensures the survival of a species when it is subjected to stress, such as disease or adverse environmental conditions, allowing it to adapt to changing climates.

Vavilov’s example was replicated by governments in most parts of the world because gene banks were directly tied to matters of state. Rare or important species—for example, crops crucial to a national economy—could be preserved in gene banks and used as a basis for continued improvement. The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) supports several gene banks with this mission in mind. The basic method for preserving seed to ensure its long-term viability is to freeze it. In its simplest terms, a gene bank is a deep freeze that holds plant life in limbo until it can be studied or grown out again to refresh the seed. Unfortunately, because gene banks are usually government funded and linked to scientific research, they are not readily accessible to the gardeners who may want to obtain rare seeds and grow them. Gene banks do not see their mission in a commercial light. Seed sales not only would place them in direct competition with seed companies but could easily become an added bureaucratic burden, sidetracking them from important research. Shortage of government funding, however, is changing this attitude.

The Institut für Pflanzengenetik und Kulturpflanzenforschung, a state-sponsored gene bank at Gatersleben in the former East Germany, is now forming working agreements with such private seed-saving organizations as Seed Savers Exchange in Decorah, Iowa, and Arche Noah in Schiltern, Austria. Many heirloom vegetables, such as the Riesentraube Tomato (shown here), now in circulation among members of these two organizations, can be traced to Gatersleben. Of course, a number of American seed savers are also accessing USDA collections in this country, and this is greatly expanding our heirloom vegetable lists. The Puhwem and Sehsapsing (shown here) corn came from seed obtained directly from the USDA.

Meskwaki Red Dent is an Iowa heirloom originating from the Meskwaki Nation.

GENETIC DIVERSITY AND ENVIRONMENTAL ACTIVISM

Genetic diversity is one of the cornerstones of the heirloom seed movement. Just as it expresses itself through a broad spectrum of concerns, so there are several types of gardeners drawn to it, from those with complex philosophical readings on the meanings of the earth and mankind’s role here to outspoken critics of agribusiness and government.

Alan M. Kapuler’s former Peace Seeds, which became part of a collaboration with Seeds of Change under the name of Deep Diversity, produced heirloom-seed catalogs based on the theories of botanist Rolf Dahlgren, whereby all plant life is organized into major kinship structures and “coevolutionary layouts” resembling genealogical fan charts. Plants are selected for molecular properties, biodiversity, and their role in providing amino acids essential to building proteins. Diet and nutrition are therefore embedded in such holistic approaches, a reordering of philosophical priorities oftentimes at odds with the old Judeo-Christian worldview.

The usefulness of the heirloom vegetable in fulfilling certain spiritual sensibilities finds its expression across the board among American seed savers, from the followers of Rudolf Steiner, whose biodynamic agriculture is essentially a theory of nutrition based on soil-building techniques, to born-again Christians who come to Jesus in their gardens. Without taking a position on any of these views (other than what I have already stated in my introduction), I think it is essential to point out that it is this very diversity of purpose that gives the seed-saving movement its continuing energy; as with plants, diverse ideas fertilize one another. What we cannot afford is a monocultural perspective. It was monocultural thinking that caused the potato famine. We study its agony in history books, but have we learned its lesson?

Most of the varieties of potatoes being raised in Europe and North America up to the 1840s were genetic clones of a handful of potatoes brought out of South America during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A clone is a plant (or animal) that is genetically identical to its parent. We make clones of potatoes because we cut up the tuber and raise new plants from these pieces, rather than from seed. We do the same when we take grafts from fruit trees. Clones of this kind are not really heirlooms; they are living history, genetic replicas of their ancestors.

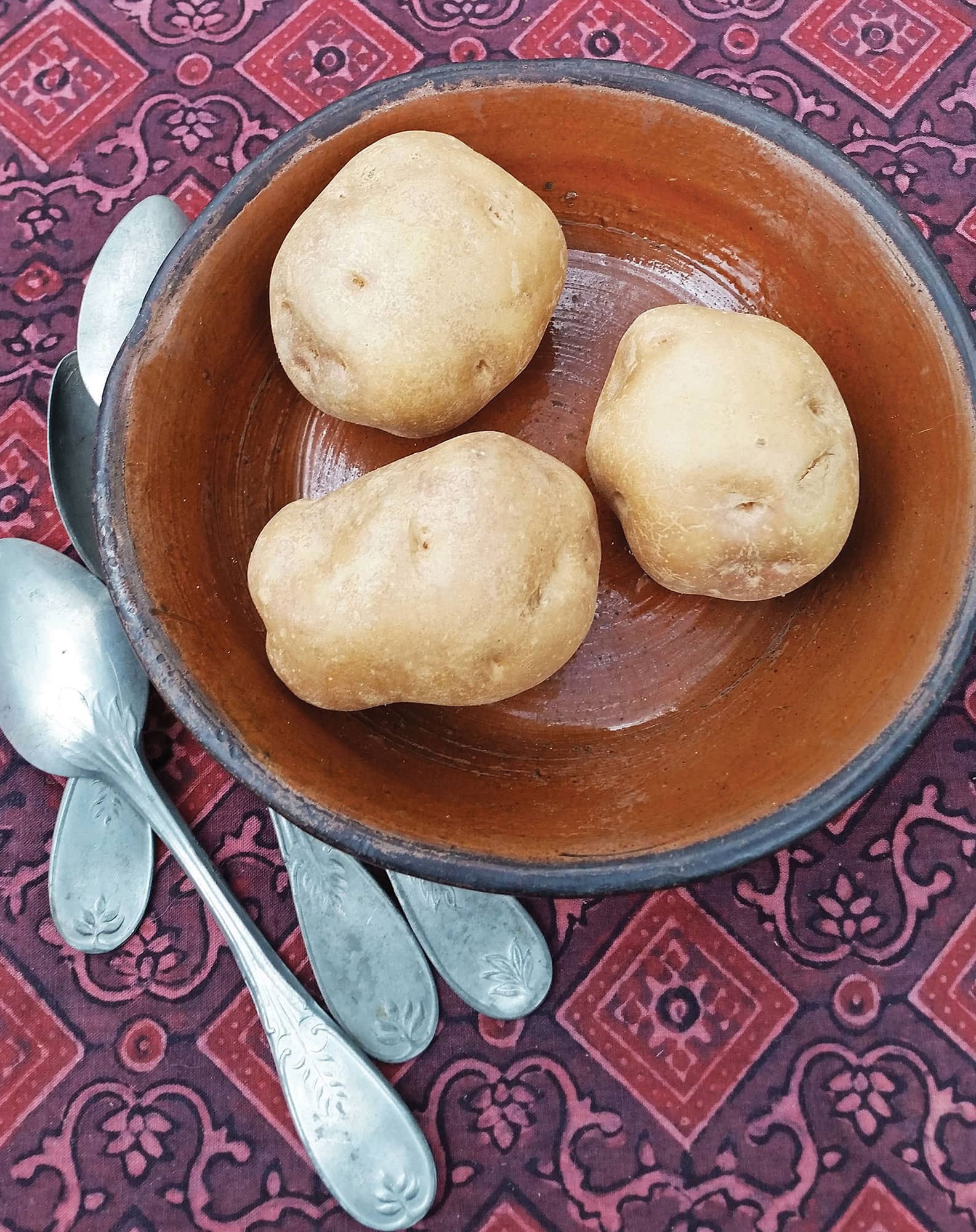

The problem with the clone potato population in the 1840s lies in the fact that because the potatoes were so closely related, they all carried the same genetic strengths and weaknesses. The disease that struck the European potato fields, decimating the crop almost overnight, originated in Mexico. Mexican potatoes, over years of exposure to the disease, had produced strains of plant more resistant to it. The South American potatoes had not. Thus, in a very short period of time, the potatoes were wiped out due to their narrow genetic base, and millions of people starved. The heirloom potato that caused the great Irish potato famine was The Lumper, depicted in the photo at right.

Today, the hybrid vegetables that are being promoted over the old heirloom varieties contain the genetic weaknesses of monocultural cultivation. While it is true that geneticists can carefully breed hybrids to be resistant to certain known diseases, that Huge Unknown—the newly mutated virus—may undo their handiwork overnight. This has become especially frightening to some gardeners, and there is a strong grassroots movement to grow heirloom vegetables as a hedge against massive crop failures in the future. Part of this movement are a number of small seed companies (listed here) that cater to the heirloom market and are continuously reintroducing exciting old varieties from their trial gardens. Seeds Blüm was even generous enough to send me seed samples or some vegetables a year or so in advance of their release to the public. That sort of cooperation, and a sincere willingness to help, is a common bond among seed savers. Support for the small seed companies is one way to help keep food production in the hands of the consumer.

The Lumper is a pre-1770 variety that became almost universal in Ireland. For lack of biodiversity, this is the potato that failed in the 1840s and caused the Great Famine.

The great fear among European gardeners was that the European Parliament would pass certain legislation brought up as draft law in 1988. This was the Legal Protection of Biotechnological Inventions act, which stated that plants, animals, and human genes would be patentable, and that farmers would not be able to save seed from their crops and freely reuse this seed for crops the next year. Patented crops and livestock would require annual royalties—as high as 80 percent of the original seed cost—from any offspring. The public outcry against this was enormous, and in the spring of 1995 the law was voted down, but the political situation in Europe is still unsettled, and it is against the law to sell seed for plants that are not on national seed registers. This includes a vast number of heirlooms not presently sold by commercial seed houses. Not even the Henry Doubleday Research Association in England, a nonprofit foundation, can sell seed from its collections to help underwrite its stated mandate.

With a similar specter of legislated extinctions hovering over us, American activism against the “patenting of life,” as it is called in Europe, has assumed large-scale proportions. Even the Christian right has gotten involved, because the environment is viewed as God’s work, and there are clear scriptural mandates to respect and maintain it. However, the most direct counterattack has come from brilliant plant breeders such as Tom Wagner in California, who created a large number of tomato varieties the old way and released them through his tiny Tater Mater Seed Company (now out of business). His cross between two heirloom tomatoes, Yellow Fig (shown here) and Evergreen, resulted in Green Grape, one of the most popular small tomatoes today. Another of the Wagner creations is Green Zebra. With Alice Waters promoting his tomatoes at Chez Panisse, her restaurant in Berkeley, and produce farmers taking up the cause, this type of genetic guerrilla warfare can quickly undermine the profitability of such patented bioengineered vegetables as the Flavr Savr™ tomato, which has been marketed under the brand name MacGregor’s, the true Dorian Gray of the tomato kingdom.

Sustainable agriculture has been another venue of resistance to agribusiness, with small-scale farmers providing local markets with an array of specialty produce unavailable through long-distance shipping. Biointensive minifarming is one new name for it. It focuses less on standard farming techniques than on new ways to coax large harvests from small areas of ground.

The Common Ground Garden and Mini-Farm at Willits, California, has been taking the lead in promoting small-scale agriculture, not to mention its heirloom seed offerings through the Bountiful Gardens catalog. Through its publications, workshops, and interns from Third World countries, much attention is focused on intensive farming techniques useful to anyone involved with kitchen gardening: compost crops, double-digging, hexagonal plant spacing, manual tools, and such traditional ethnic growing methods as lazy bed gardening, from Ireland. Lazy beds are built up above ground level, and the soil is deeply worked, with yields similar to those of the raised gardens of the Pennsylvania Dutch.

ETHNOBOTANY AND THE AMISH VEGETABLE

In an article about the Landreth & Sons seed company, which appeared in the Pennsylvania Farm Journal (1853, 136), a description of the firm’s “Bloomdale” trial farm near Philadelphia provided a fascinating glimpse into the state of horticulture in this country in the years preceding the Civil War. In 1853 Landreth devoted fifty acres to peas, an impressive figure but not altogether surprising given the Victorian love for peas of all sorts. More startling, Landreth reported sending four tons of vegetable seeds to India, and similarly large quantities to California, New Mexico, South America, and the West Indies. Today, seed collectors are traveling through India, South America, and the West Indies in search of “native” varieties. In fact, many of these heirloom vegetables may have started in seed packets from somewhere else more than a century ago.

Simple purity or life close to the land, whether of the peasant in Thailand, the Hopi Indian in New Mexico, or the Amish farmer in Iowa, has enormous appeal to Americans alienated by the complexities of modern urbanized living. This yearning for rustic simplicity is evident everywhere in our attitudes to rural life in general, and in the way we present food in restaurants and magazines, not to mention in mass media advertising. The “natural” foods of the tropical rain forest, the “purity” of crops tilled by the American Indian, the sacred character of the Amish commitment to the land—these are recurring themes of an intensely appealing kind and express themselves everywhere in the seed-saving movement.

Indeed, one of the earliest uses of the term heirloom in connection with seed saving came from an American Indian context. An article on “Indian Vegetables” in Meehan’s Monthly (October 1892, 156) noted that a reader of the magazine in Tennessee living near a community of Cherokees had obtained a snap bean from a chief named Silver Jack and that the bean was being maintained as an “heirloom.” Unfortunately, Silver Jack’s snap bean was not described in enough detail to connect it to a variety known today, unless by some coincidence it happens to be the Jack’s snap of Seed Savers Exchange. Otherwise, it may be extinct or preserved under another name.

It is easy to overromanticize the American Indian role in seed preservation, even though evidence may seem quite compelling. The forced removal of peoples from their historical lands, the collapse of one group into the other, and the predominance today of the largely nomadic Great Plains cultures as an overarching symbol of the American Indian have taken their toll on the original diversity of Native American foods and foodways. Yet there are some bright spots.

Quaker relations among the Iroquois between 1795 and 1875 have recently been explored by Professor Carol Karlsen of the University of Michigan. Implicit with the cultural impact of Quaker attempts to bring education and progressive farming methods to the Iroquois was the distribution of seed. It is difficult to know whether the Scotia, or Genuine Cornfield Bean (shown here), of the 1820s was a commercial introduction to the Iroquois or a native variety improved by American seedsmen. Likewise, the Delaware Indian Turtle Bean is also the Fisherbuhn of the Pennsylvania Dutch, and the Dutch Caseknife (shown here) of Europe, a very old European variety, incidentally.

In their Description of a Journey and Visit to the Pawnee Indians (1914; the trip occurred in the spring of 1851), Moravian missionaries Gottlieb Oehler and David Smith took pains to describe the Pawnee way of life. Yet they did not make detailed reports on Pawnee ethnobotany, the plants used by the Pawnee as food and medicine. They do not even provide confirming evidence that the very beautiful brown-speckled Pawnee Bush Bean (shown here) now so popular among seed savers is actually an original Pawnee variety. The bean’s botanical traits—compact bush, uniform pods, lack of runners—all point to the intervention of sophisticated plant breeding. When this bean is grown side by side with a number of old European bush varieties, there are startling similarities that suggest it probably was introduced (or reintroduced) to the Upper Midwest by German settlers in the 1850s or 1860s. Only where Native Americans have lived in relative isolation from white contact can we be more certain of the plant origins.

Gary Nabhan’s award-winning research among the desert peoples of the Southwest is often cited as a model for the collection and documentation of native plant species. Nabhan is a true ethnobotanist fully committed to carrying the seed exchange back to the peoples of origin, especially in the Sonora Desert, where he engages in research. Most important to growers of heirloom plants, Nabhan was one of the founders of Native Seeds/SEARCH in Tucson, Arizona. This organization publishes seed catalogs for plants from the Sonora region and is directly involved in helping native peoples reclaim their traditional food cultures.

In the same way that Indian earth connectedness has fascinated modern American gardeners, “Amish” has been absorbed into the vocabulary of seed saving. Varietal names such as Amish paste tomato or Amish Walking Onion for the tree onion indicate not so much an Amish-bred vegetable as an approved seed source for the plant, for the word Amish implies a relationship to the land, a source unspoiled by pollution, chemical fertilizers, and unethical farming practices. Very few Amish have been involved in commercial plant breeding. I can only think offhand of Isaac N. Glick of Lancaster, who was not only in business at the turn of the last century but also made significant contributions by developing or promoting a number of new vegetable varieties. Glick introduced his Eighteenth Century beet, a long, dark red beet with bright green leaves, in 1906. He also offered many heirlooms still popular today, such as Stowell’s Evergreen Corn (shown here), Early Snowball Cauliflower, Icicle Radish (shown here), Hackensack Melon (shown here), Golden Ball Turnip (shown here), and Champion of England Pea (shown here). The Glicks are still in business, and to them I owe a special debt of gratitude for my greenhouse.

The Nanticoke Winter Pumpkin is a rare variety preserved by the Nanticoke Indians from the Maryland Eastern Shore.

However, the Amish are great seed savers, and many old vegetable varieties have been preserved in their gardens. Because these vegetables often come down without their original names, they acquire backyard designations that can seem confusing to anyone trying to sort out plant histories. A classic example of this is the well-known Brandywine Tomato (shown here), which was developed not by an Amish farmer, as popular legend would have it, but sent out into the world by the Johnson & Stokes seed company of Philadelphia. The real Amish vegetables come from seed collectors such as Rebecca Longenecker of Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania. She has supplied me with a wonderful selection of seeds garnered from her Amish neighbors, including the Hersh Sugar Pea, an unnamed soy bean, and the Gross Nanny Green Pole Bean (shown here). The pole bean is the same as von Martens’s Halbrothe Kugelbohne (1869, 76); the dwarf form is called the Beautiful Bean in the Beans of New York (Hedrick 1931, 76) and the Zuiker Boon from the Cape of Good Hope. In England it is popularly known as the Pea Bean and is still sold by some seed houses. It appears to be a very old cross between the white marrow pea (shown here) and the Red Cranberry Pole Bean (shown here). In the United States, small marrow beans were often called pea beans.

The Landis Valley Museum near Lancaster, Pennsylvania, has undertaken a massive project to collect and document the ethnobotany of the Pennsylvania Germans and their North American diaspora. Many of the discoveries of the Heirloom Seed Project are now available through an annual seed catalog that includes a fascinating array of heirloom plants. Landis Valley has been responsible for introducing several rare Pennsylvania Dutch heirloom vegetables into seed-saving networks, including the Red Brandywine Tomato and the Amish Nuttle Bean (shown here). The museum’s primary focus, however, is the periodization of its plant collections—that is, placing the vegetables and fruits in their correct historical settings. Landis Valley is an open-air museum, a collection of houses replicating a farm village, and as such it is only one of a large number of historic sites in this country that view heirloom vegetables as living antiques.

THE HISTORICAL GARDENER

The Skansen movement in Sweden during the 1890s gave birth to the concept of the open-air museum re-creating peasant life as a metaphor of cultural identity. Entire villages were reconstructed, with historic buildings dismantled and reassembled to establish a mood and setting reminiscent of the formative years of the nation’s persona. Not surprisingly, at the heart of these buildings were kitchens, dark, smoky rooms where ladies in archaic garb prepared dishes on an open hearth symbolic of the cultural struggle between life on the land in former times and the enticements of today’s well-stocked supermarket.

Skansen is now a term in many languages for an open-air museum. This concept has translated itself into historical sites in the United States, from towns such as Mystic, Connecticut, and Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia to Pleasant Hill of the Shakers in Kentucky and restored Spanish missions in the Southwest. In each case there is a historical interest in the kitchens, in the foods prepared, and in the gardens that supplied the households with produce. The promotion of women’s studies and the study of various functions of women in traditional farming societies have greatly added recent momentum in heirloom gardening as a study in period vegetables.

The National Colonial Farm at Accokeek, Maryland, began raising colonial farm crops of the Chesapeake region more than twenty years ago. Old Sturbridge Village at Sturbridge, Massachusetts, began collecting New England heirloom vegetables, including varieties disseminated by the Shakers, well before the US bicentennial. The bicentennial caused many American gardeners to reassess their historic roots, encouraging a renewed interest not only in early American life but also in the various ethnic communities that cultivated distinctive kitchen gardens in the nineteenth century. As a result, heirloom gardening in this country has become far more complex than in England, for example, because of the large number of overlapping cultural histories that make up our national character.

As a case in point, I could offer Hans Buschbauer’s Amerikanisches Garten-Buch (1892), published as a guide to the German-American kitchen garden in the Upper Midwest. When one reads through this book, it becomes obvious that the author has accommodated his garden ideas to North American conditions. He recommends just as many well-known commercial American vegetable varieties from the 1880s and 1890s as older, more traditional ones. Indeed, telltale woodcuts from the Vilmorin Le Jardin potager (1885) creep into his text, and there are certainly touches of up-to-dateness in his discussions of Defiance lettuce (very much talked about at the time) and crosnes (Stachys affinis), a root vegetable from Asia that had only been introduced to American gardeners in 1889. Thus the ethnic sketch of Buschbauer’s kitchen garden became a very mixed bag of vegetables indeed.

Recently the Monticello Foundation has taken an interest in Thomas Jefferson’s mountaintop vegetable garden, a terraced affair with a spectacular view toward the southeast. Jefferson’s gardening interests are well documented, and the names of the varieties of vegetables he grew can be located in early garden sources. To bring this aspect of Jefferson’s daily life into better focus for visitors to his house, an extensive plant collecting program has been undertaken. It supports itself financially in part through the sale of plants and seeds with Jeffersonian associations. Under the recent direction of Peter Hatch (now retired), it has been highly successful.

Because of the nature of seed saving and the genetic shifts that occur in plants propagated this way, it is difficult to find vegetables dating from Jefferson’s period (pre-1826) that exactly match those that he grew at Monticello. In fact, documented vegetable varieties predating 1800 are even rarer and may not number more than a few hundred. This is not many, considering that there are today several thousand tomato varieties, and this does not even begin to touch the numbers of such vegetables as fava beans, peas, or radishes. In any case, Monticello has become a leading force in the preservation and dissemination of early American plant varieties, especially with an eye toward their documentation and their role in Jefferson’s garden schemes.

SEED SAVERS EXCHANGE

The heirloom seed movement in this country has now coalesced into a unified effort for all the reasons I have just discussed: concern about the environment; a new interest in food history; and a sense of loss over disappearing plant varieties, perhaps with terrifying implications for the future. A small group of gardeners sharing these concerns organized in 1975 under the oversight of Kent Whealy, then of Princeton, Missouri. Thus Seed Savers Exchange was born.

Seed Savers Exchange is now the largest grassroots organization of its kind in the United States. It has relocated to Heritage Farm at Decorah, Iowa, established extensive seed collections, and has been involved in gathering threatened plant varieties in the former Soviet Union, and indeed in all parts of the world. The exchange has undertaken an active publication program, and many books, such as Suzanne Ashworth’s Seed to Seed (1991), may be considered among the most useful of their kind, whether for raising heirloom vegetables or simply for gardening pleasure.

Some members of Seed Savers Exchange (SSE) also maintain large seed collections of their own, such as special collections of corn, sweet potatoes, or squash. My own Roughwood Seed Collection, begun in 1932 by my grandfather, is the largest private seed collection in Pennsylvania, with an emphasis on heirlooms from the mid-Atlantic states. Over four hundred heirloom varieties from the Roughwood Collection have gone into the SSE archive. Other members have built seed collections around a specific region or time period. These satellite collections contribute samples to the seed collection at Heritage Farm and in many cases help maintain the seed purity of certain endangered varieties. Nearly all of the satellite collections offer their seeds only through the annual SSE seed listing; thus, membership in the organization becomes a membership in a vast worldwide network of interlinked seed savers. With a little patience, it is possible to locate almost any known heirloom vegetable, provided that it is not extinct. Every vegetable profiled in this book is available through Seed Savers Exchange or through the specialized seed firms listed here.

Buena Mulata is one of the most popular peppers in the Roughwood Seed Collection. It was acquired in the 1940s from American folk artist Horace Pippin.

Seed savers in other countries, in particular Arche Noah at Schloss Schiltern in Austria, have modeled their seed organizations after Seed Savers Exchange. Arche Noah has been concentrating on heirloom vegetables from German-speaking Europe as well as from the former Iron Curtain countries of Eastern Europe. Under the old Communist governments, considerable money was devoted to preserving traditional foods at open-air museums and gene banks, but now that the money is gone, and with no funding in sight, Eastern Europe is losing large amounts of rare genetic material every year. The task that Arche Noah has cut out for itself is enormous; the name that this organization has chosen for itself (Noah’s Ark) could not be more appropriate.

Some seed organizations have evolved quite independent of Seed Savers Exchange, but now cooperate closely with it. The most famous of these is the Heritage Seed Programme at the Ryton Organic Gardens, Ryton-on-Dunsmore, near Coventry, England. This seed collection, first organized in 1958 by horticulturist Lawrence Hills, was named in honor of Henry Doubleday, a nineteenth-century English Quaker. The Henry Doubleday Research Association (HDRA) is the parent organization that oversees the various projects at Ryton. Like Heritage Farm in Decorah, Iowa, Ryton Organic Gardens are open to the public. More than 18,000 members of the seed program at HDRA receive a selection of free heirloom seeds every year as part of their membership privileges. I have added a number of unusual plants to my collection in this manner.

Lacking in all of these efforts, however, is one essential element. While much time and effort have gone into preserving seed of heirloom vegetables, no one has undertaken extensively to identify and document their histories or their many culinary uses. Oral history and folkloric tales are sometimes useful in piecing together the underlying reasons for why a given heirloom vegetable was saved, the Cherokee Trail of Tears Bean (shown here) being a prime example. We would understand more clearly the relationship such heirlooms had to one another—black pole beans arranged into related botanical groups, in the case of the Cherokee bean—and why these variant forms were developed if we had access to some type of plant genealogy. Surprising things come to light when we explore in depth plant histories such as that of Stowell’s Evergreen Corn (shown here) and why it got that name. The plant profiles in the following chapter are intended to fill this need.