Two

SPORTING BEGINNINGS

Many tourist parties have enjoyed skiing and other sports.

—The Littleton Courier, February 16, 1911.

Woodland expeditions for men and women in the early 20th century often included skiers along with the more numerous folk on snowshoes.

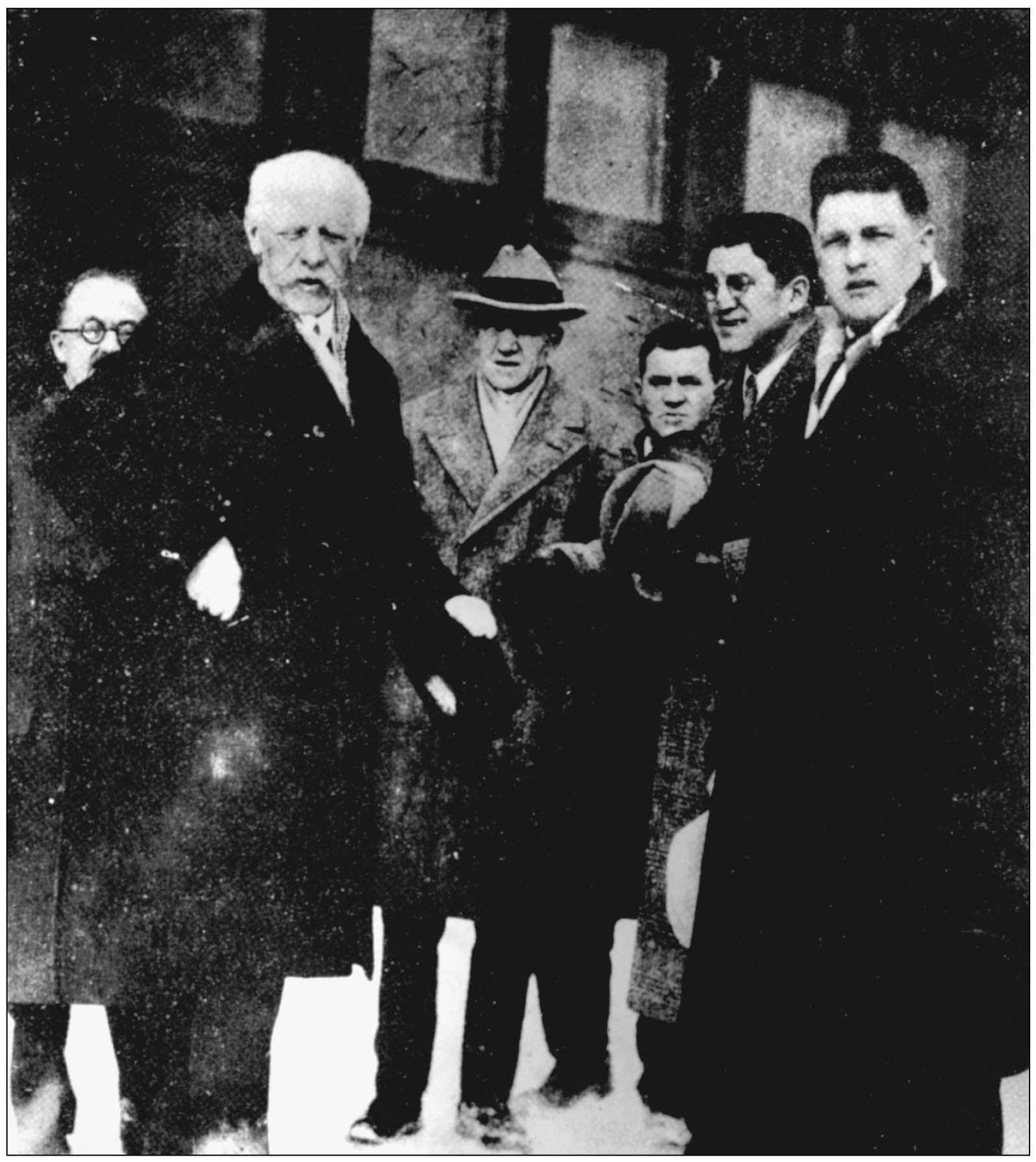

The most important early center for skiing in the state was Berlin. Norwegian immigrants formed a club, which came to be called the Nansen Club in honor of famous Norwegian explorer Dr. Fridtjof Nansen (second from left), seen arriving in Berlin in 1929. Forming the greeting committee are, from left to right, John Graf, Evan “Jack” Johnson, Councilman Ramsay, Mayor Dr. McGee, and Alf Halvorsen, who did so much to promote Berlin skiing.

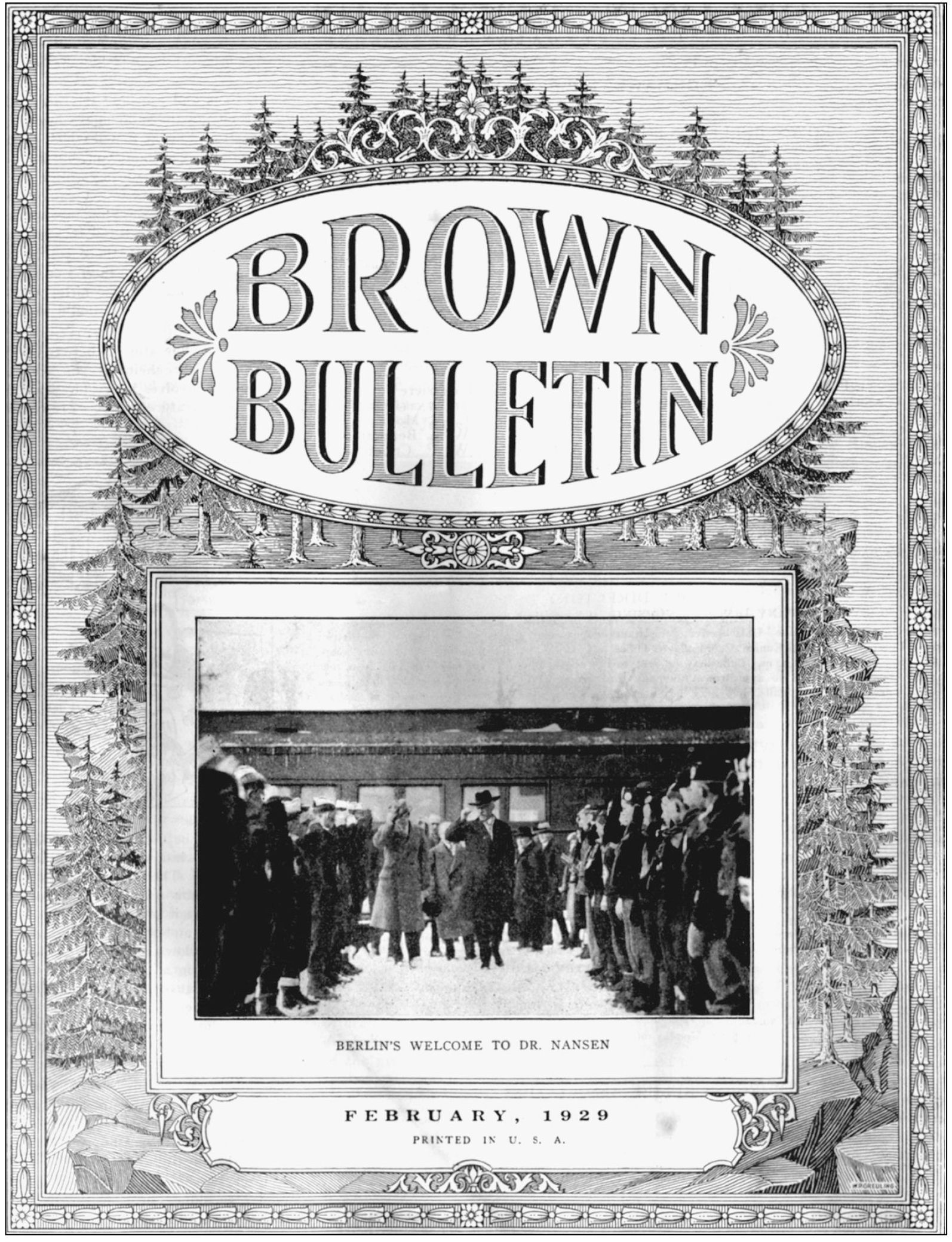

Dr. Fridtjof Nansen was greeted by the Nansen Club Juniors at the Berlin railroad station. The logging company’s magazine made much of his visit in February 1929.

This is a formal picture of Dr. Fridtjof Nansen with the Nansen Club Juniors all wearing their club sweaters and hats.

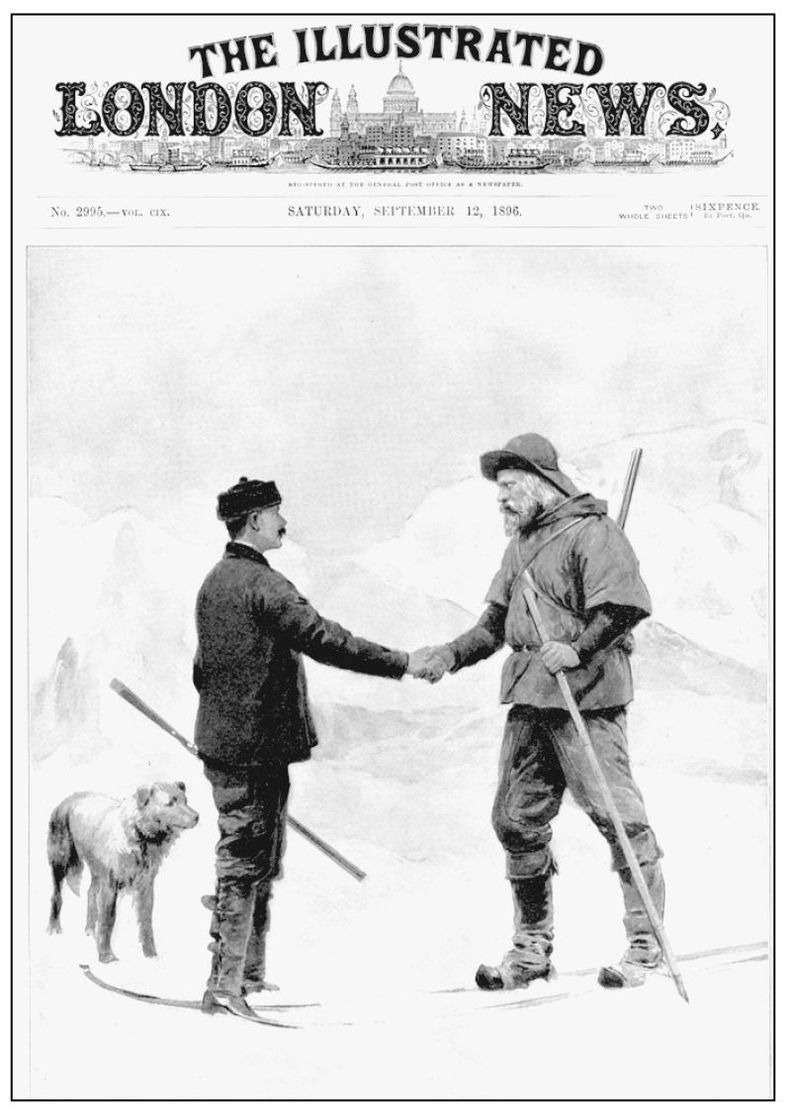

“We feared to see him lest his actual presence should dim the luster of his fame,” wrote the Brown Bulletin. Nansen’s fame rested on his crossing of Greenland on skis in 1888 and his attempt to reach the North Pole. For thousands perhaps millions of people, drawings such as the one here made visual the hero who had gone the farthest north and was, almost unbelievably, now in Berlin, New Hampshire.

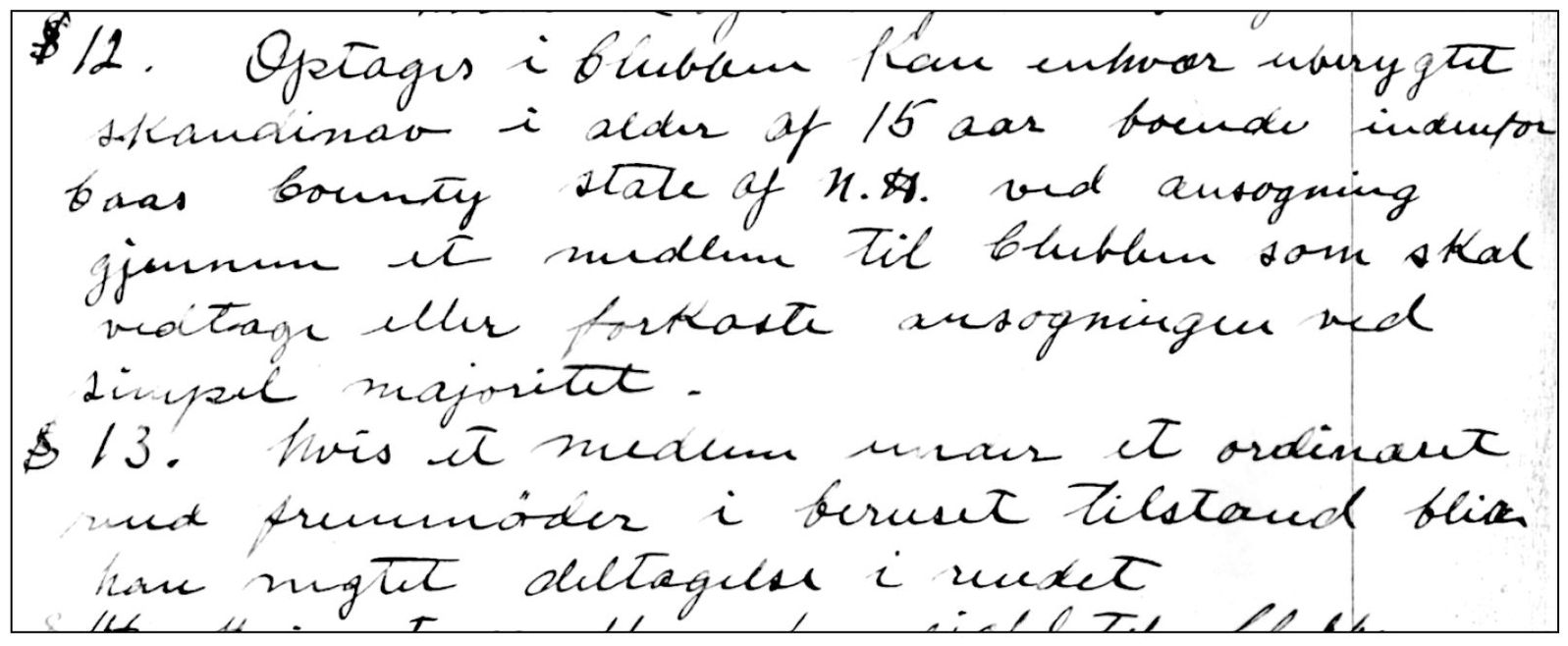

Section 12 of the Constitution of the Nansen Club reflected its early ethnic exclusiveness, for “any Scandinavian of good reputation of 15 years living in Coos Country . . . will be accepted by majority vote.” The good reputation was addressed in Section 13: “If a member comes to a regular meeting and is in a drunken condition, he cannot take part in the business of the meeting.”

Four charter members of the Nansen Club pose in March 1925. They are, from left to right, Richard Christiansen, Iver Anderson, Eric Holt, and one of the best-known jumpers, Olaf “Spike” Olsen.

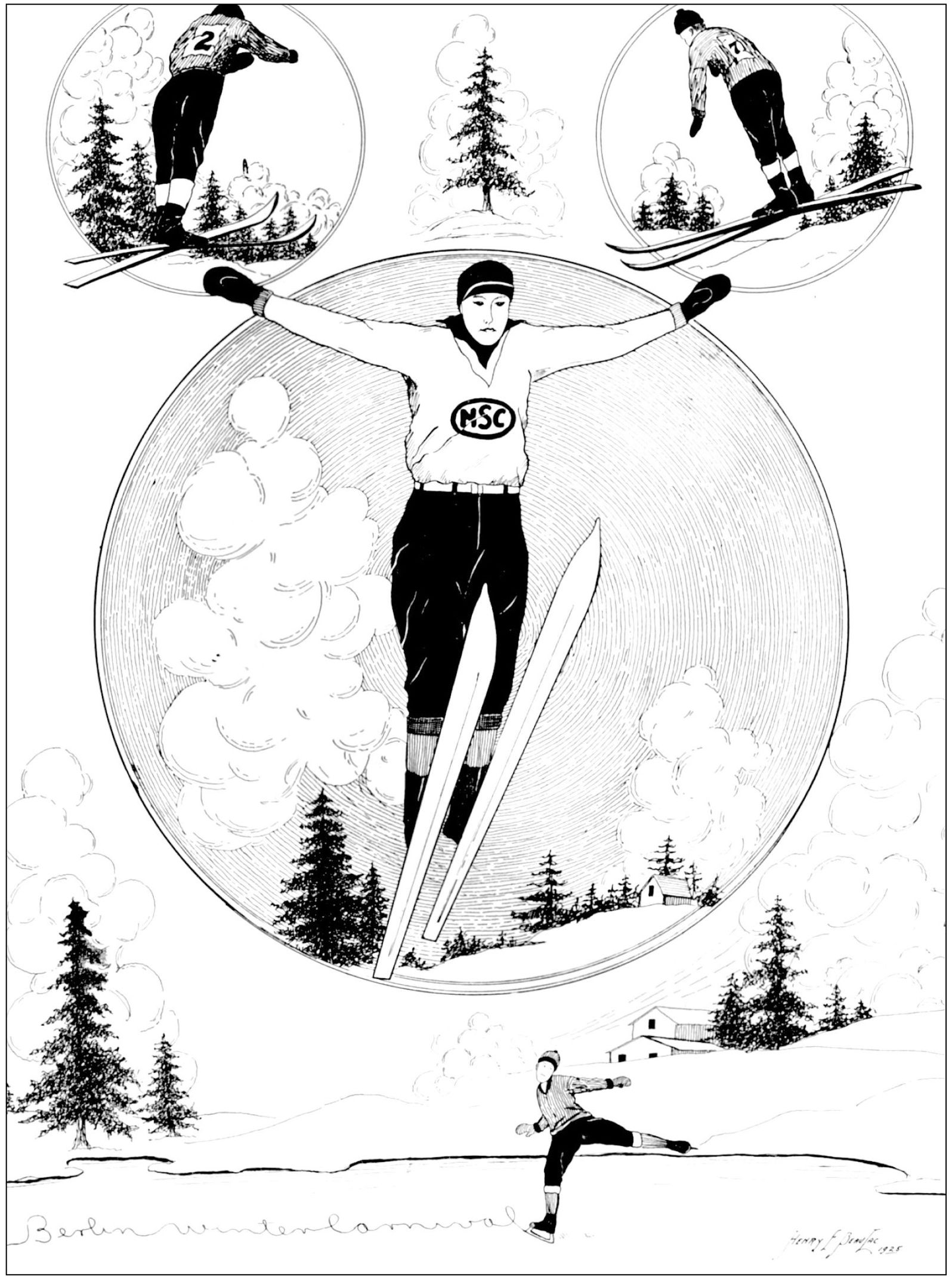

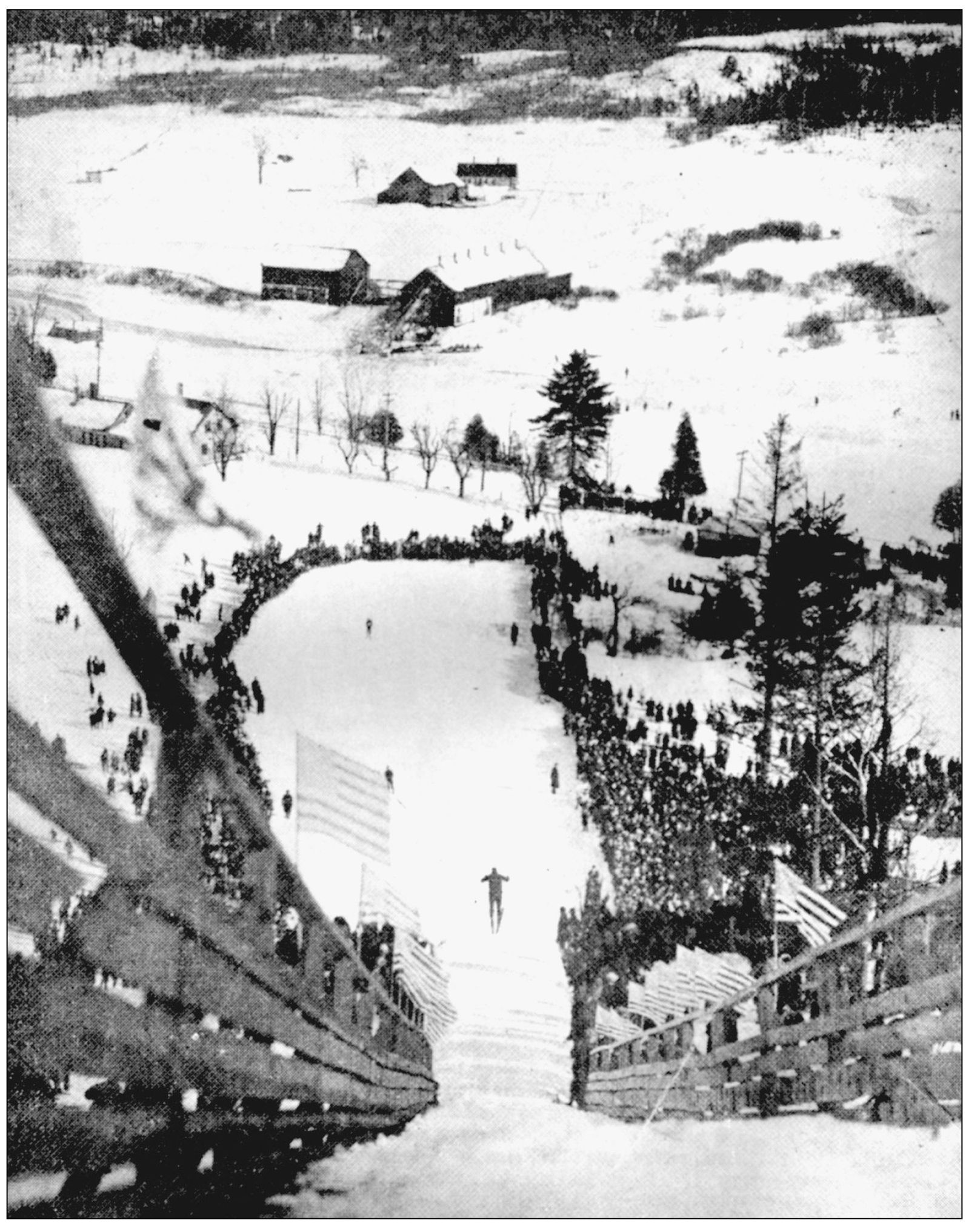

This 1925 record of the Berlin Winter Carnival illustrates the importance of jumping to the sporting community. Many small towns and communities in the state had jumps, but the Berlin jump remained the most prestigious in the state.

These kids are parading in Berlin on Carnival Day before the Junior Tournament. The Nansen Club took special care to promote skiing among children; the elders realized that the future of the club relied on bringing up the youngsters in the ski tradition.

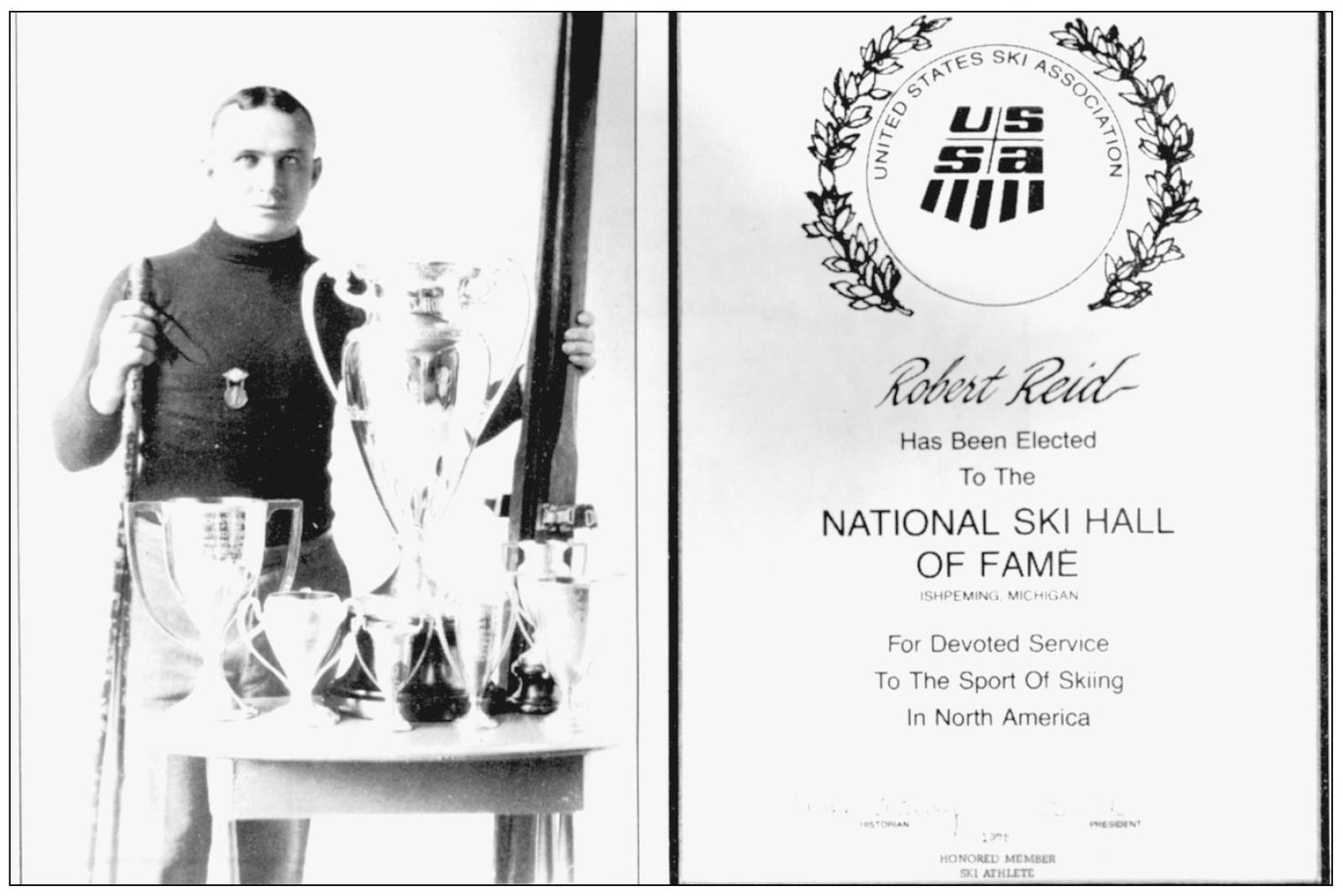

One of those youngsters was Bob Reid, who excelled in cross-country skiing. He was chosen to represent the United States (along with fellow club member Erling Andersen) in the 50-kilometer event at the 1932 Lake Placid Winter Olympics. He was elected to the National Ski Hall of Fame in 1975.

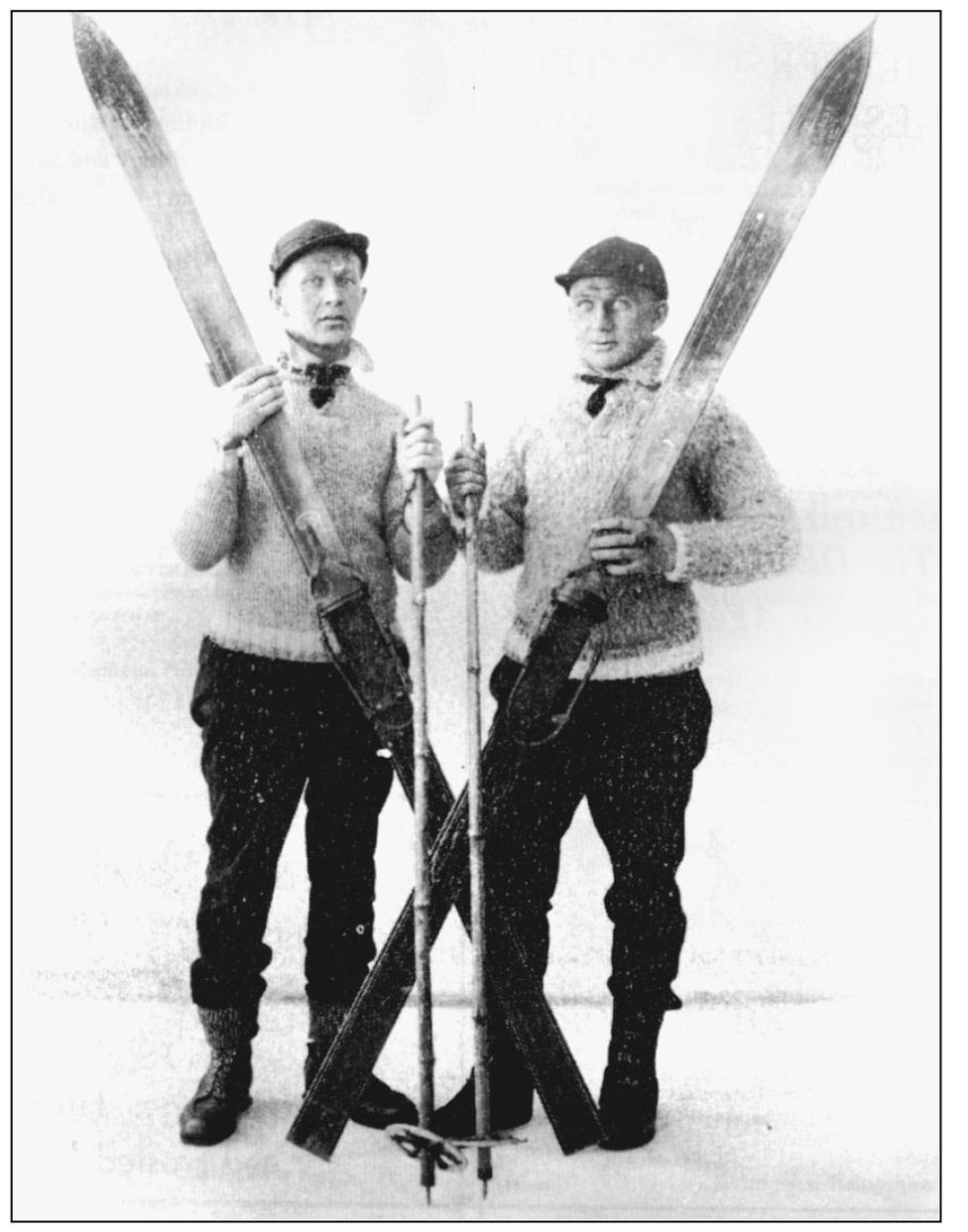

Bob Reid (right) and Helmer Oakerlund, both of the Nansen Club, were the only competitors in a 100-mile event from Portland, Maine, to Berlin in February 1926. The race was run over four days and was designed both to promote the Berlin Winter Carnival and to see if it would be feasible as an annual event. The weather decided that it was not.

This bib was worn by the two competitors for what became known as “100 Miles of Hell.” After a delayed start caused by a storm, Oakerlund and Reid rested at Gray for four hours and arrived at Poland Spring at 12:20 a.m. for their first night. On the final day, they both left Bethel at 9:30 a.m., and Reid reached the city hall in Berlin at 3:37 p.m. with Oakerlund only eight minutes behind.

Jumping in Berlin became more than an attraction with the construction of a jump at Paine’s Pasture, seen here in a photograph from 1923. In the 1920s, the jumpers were the stars of the skiing world, “knights of the air,” and Bing Anderson was the best known.

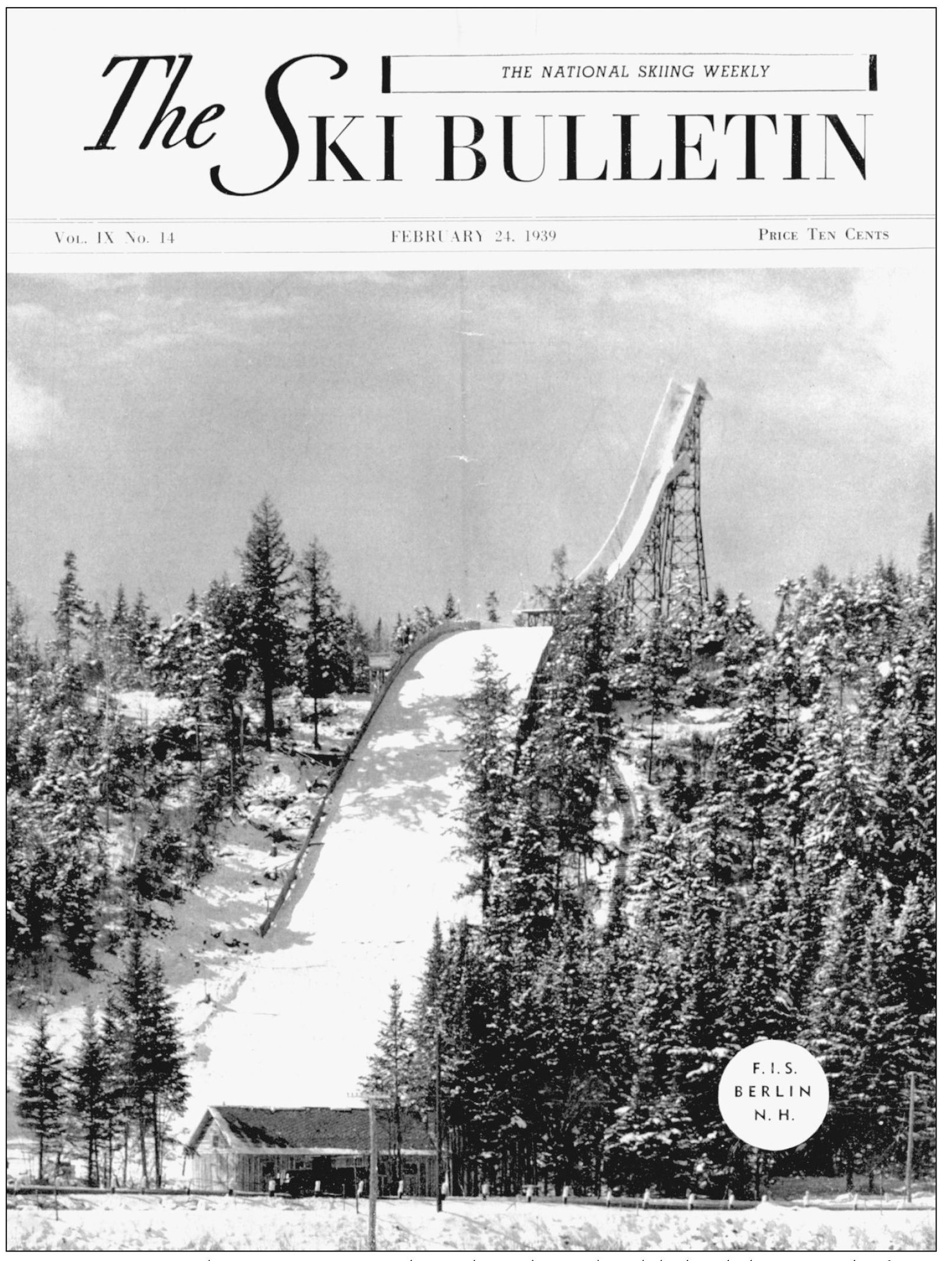

As Nansen jumpers became attractions themselves, the Berlin club decided to erect the finest jump in the East just north of the city on Milan Road. The structure stands in decay now, but there were days when men could fly over 270 feet off this famous landmark of New Hampshire, which, unfortunately, has not been put on the historic register.

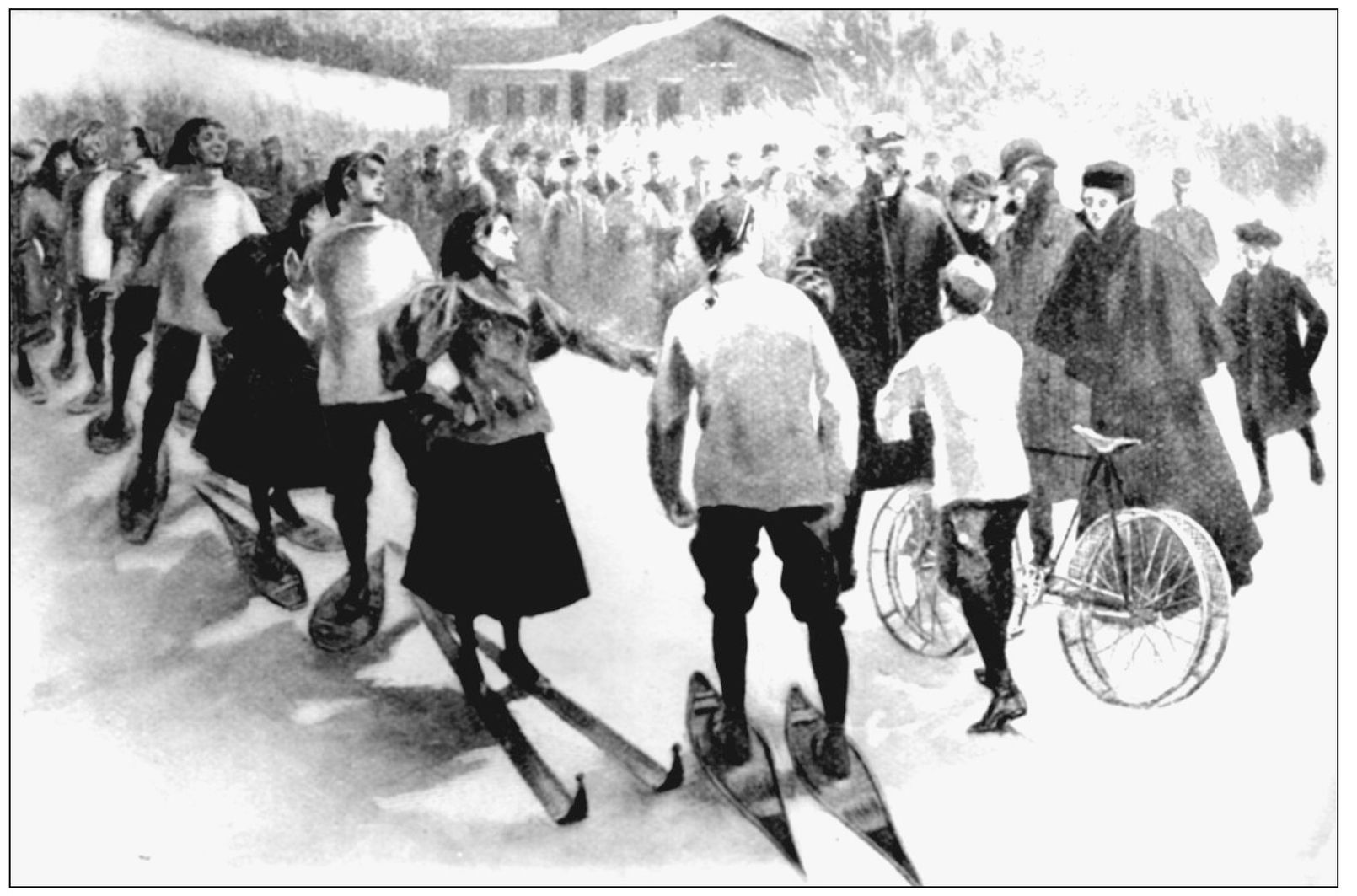

This is a school race in 1886. Note how high the tips of the skis are turned up. Skiing in those days often meant plowing through deep snows, and the high tips provided a way to cut a furrow.

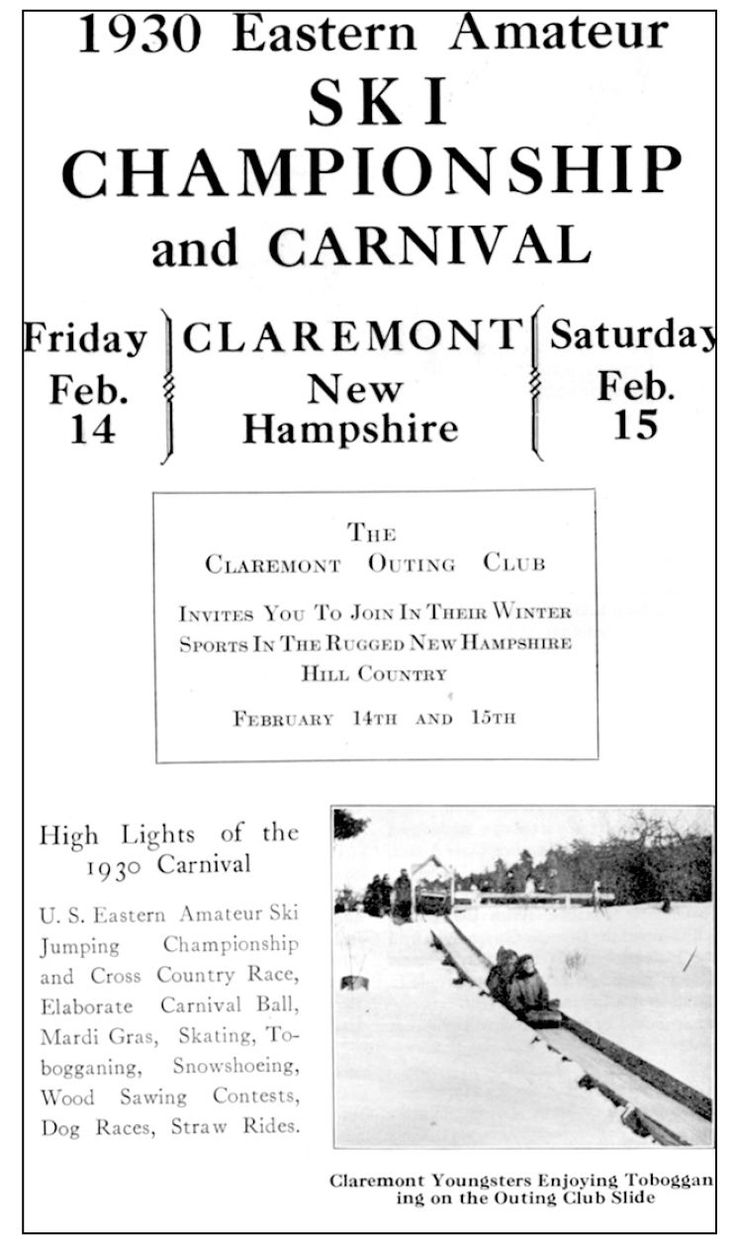

Forty years later, organized clubs were scattered all over the state. Claremont hosted the 1930 Eastern United States Championship with jumping and cross-country events along with carnival attractions of wood-sawing contests and straw rides (now hayrides). Every carnival ended with a ball.

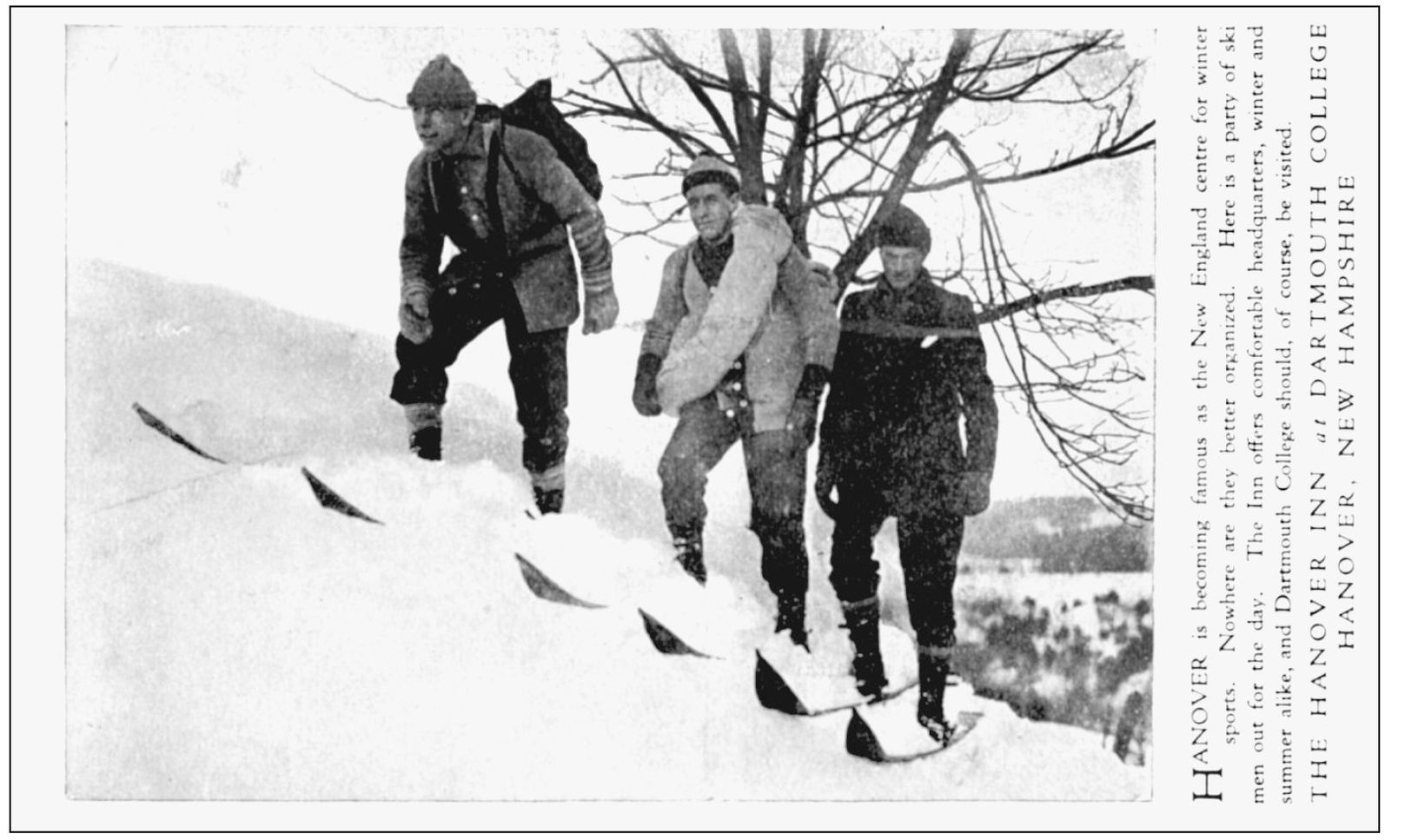

Dartmouth College in Hanover provided the venue for the first center for sporting skiing for the well-to-do. The Dartmouth Outing Club drew much of its early inspiration from immigrant skiing activities in Berlin and then gave them a collegiate ethos, such as this house party in 1913.

The Hanover Inn used Dartmouth men on skis to promote itself. Hanover was becoming known as a “New England center for winter sports,” appealing to a broader winter clientele even before World War I.

Winter Carnival weekend at Dartmouth was the great sporting and social event of the season. Besides cross-country and jumping, events such as skijoring around the Hanover common provided excitement for the guests in 1917.

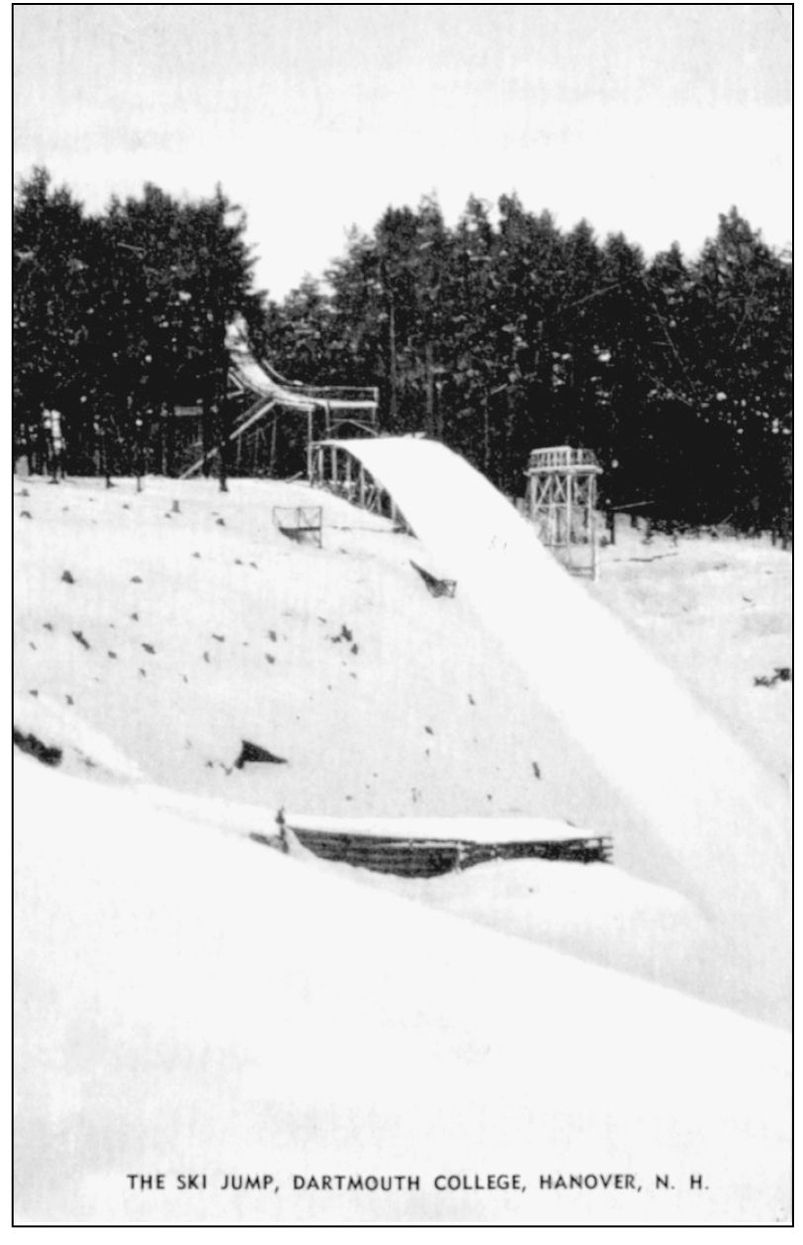

Compared to modern jumps, Dartmouth’s slide does not look particularly impressive, but it provided the thrills (and spills) for intrepid Dartmouth men who vied for honors against the University of New Hampshire, Yale, Harvard, the University of Vermont, Middlebury College, and McGill University in the early days.

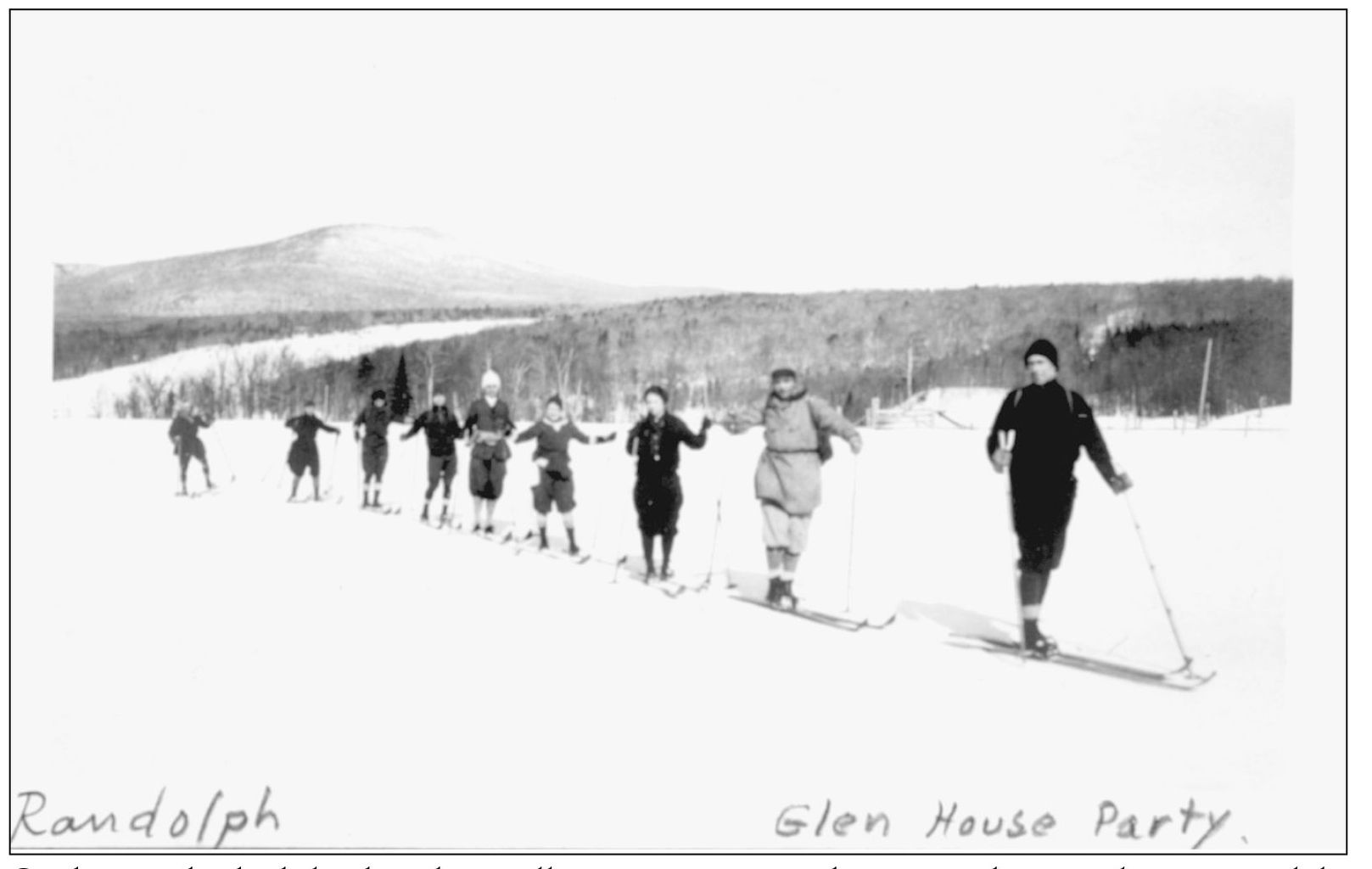

Graduates who had skied in their college years continued to enjoy the sport by joining clubs like the Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC) or formed their own parties to go to such places as Randolph and stay at the Glen House in 1926.

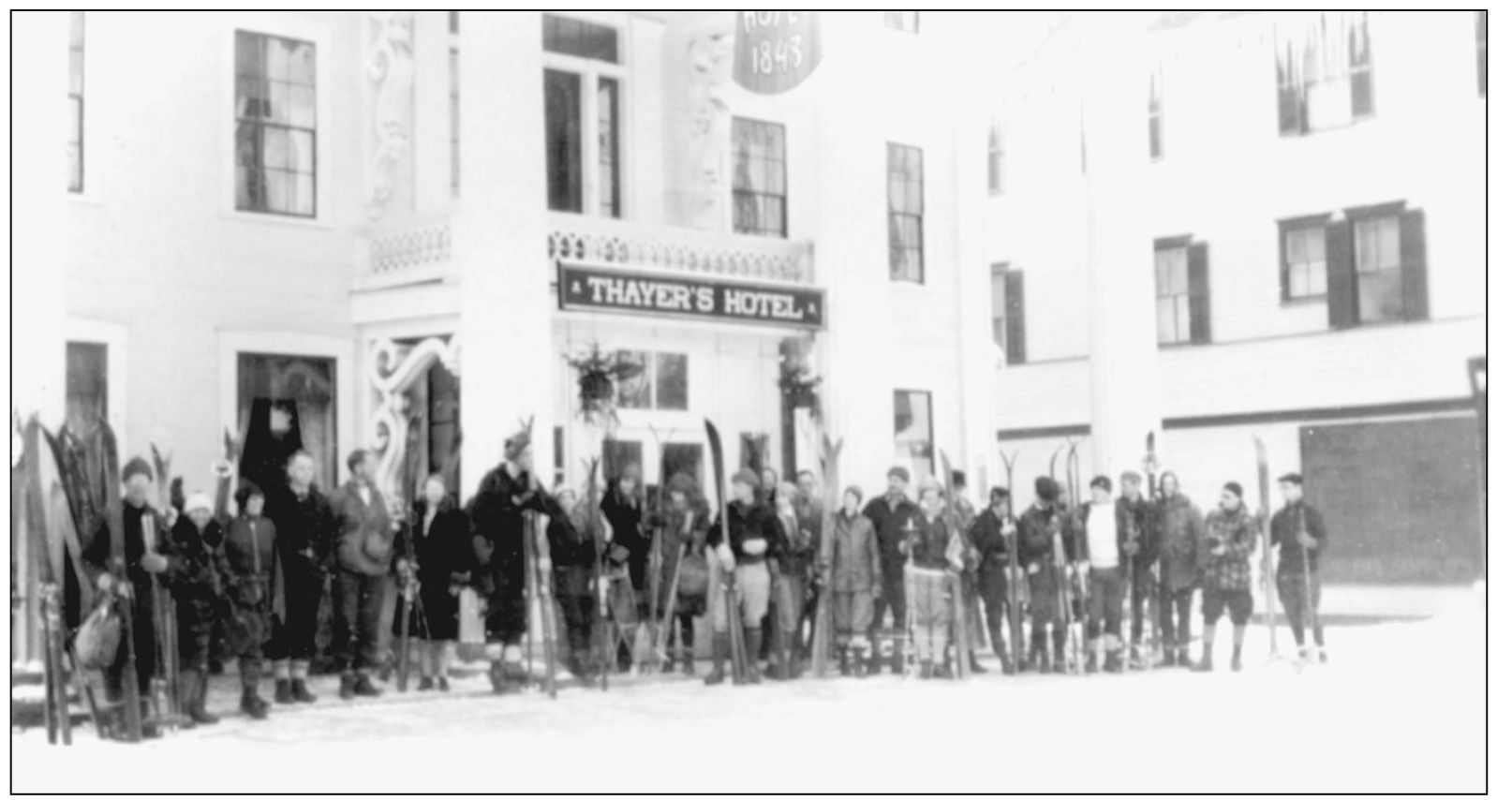

In 1929, the AMC, mainly out of Boston, organized a trip in the North Country. The group stayed at Thayer’s Hotel in Littleton, one of the few hotels to remain open in the winter and capitalize on the new winter sports.