Margaret Drabble’s Laura and Television in Britain in the 1960s

VERÓNICA MEMBRIVE PÉREZ

The medium of television in Britain grew and developed at the same time as the welfare state was transforming the social landscape of the country in the late 1940s and the 1950s, and it was associated with a kind of freshness and immediacy with social reality that was largely absent from other cultural forms of the time: “Caught in the consumer boom of the 1950s and the changing lifestyles of people eager to modernize not only their homes but also their social aspirations, British television grew up and came of age” (Hallam 2003, 4).

Compared to other, more established vehicles for entertainment, television began life at somewhat of a disadvantage: “Television in the early 1950s, (although supposedly more advanced in the UK than anywhere in the world), was very much the despised poor relation of the sound-radio corporation. Visual images were somehow vulgar, like comic strips in the back pages of newspapers” (Richardson 1993, 80). Television programs were first broadcast for a brief period before the Second World War and afterward as part of the BBC’s monopoly on the transmission of images when the service was restored in 1946, and they were confined by the limitations of good taste and public service: “Television was a young, undeveloped medium, regarded by the BBC as a subsidiary activity to the expansion of its radio networks; the BBC imbued its programmes with the same paternalistic ethos that pervaded its radio programmes” (Hallam 2003, 5).

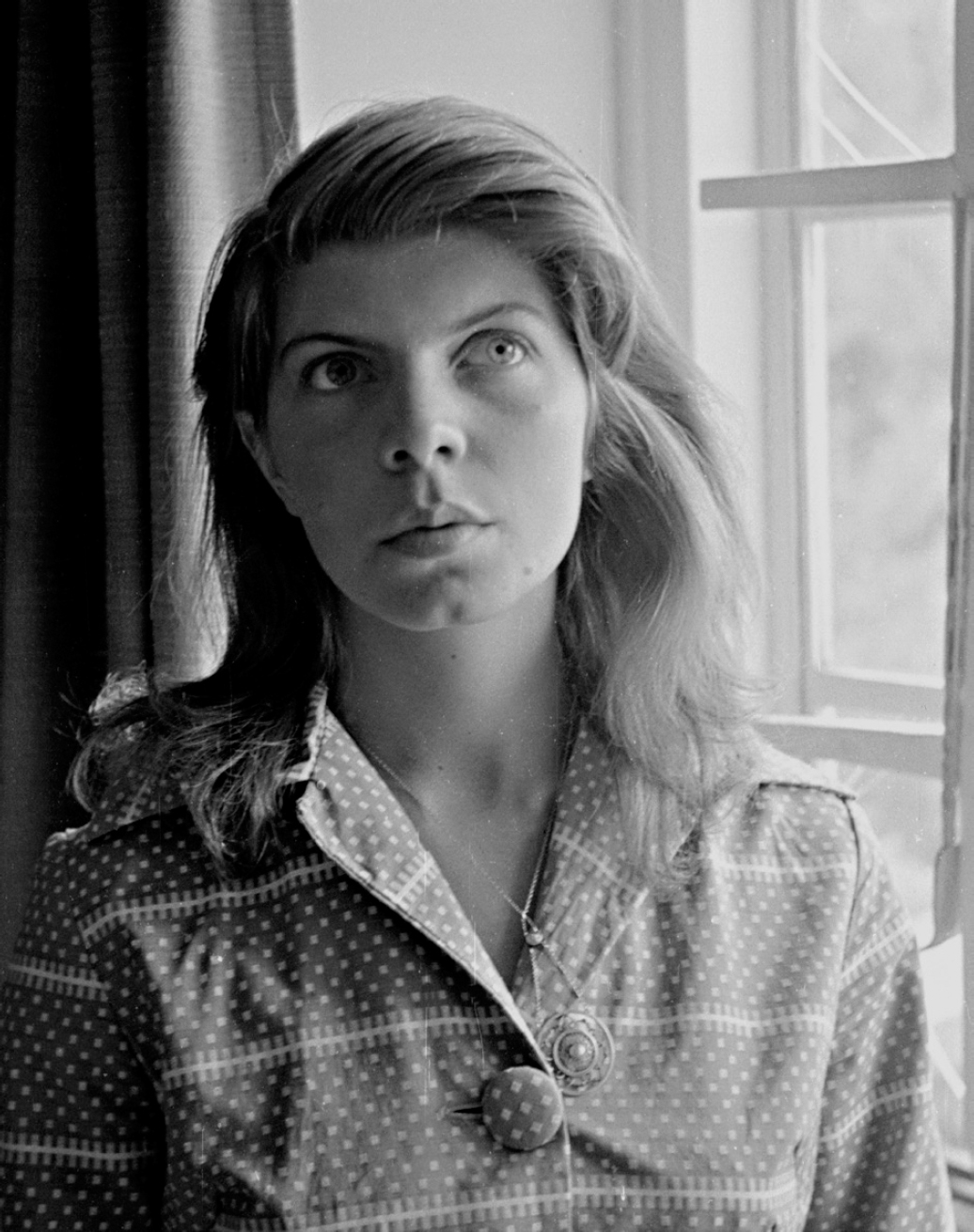

5. Margaret Drabble in her final year at Cambridge University, 1959. Photograph by Roger Bridgman. Reproduced with permission from the photographer.

The new phenomenon, however, enjoyed the advantage of starting everything from scratch, creating something that did not exist before, and this was the breeding ground for an upsurge of creativity for young talent that spread to all spheres of the recently created industry but that took hold particularly in the production of drama.

From the very beginning, plays had been part of the staple diet of television viewers. Theater was supposed to give a veneer of high culture to a medium that was populist by nature and was considered to be a necessary contrast to light entertainment. It was also inexpensive to perform in the studios (live transmission was the norm until the late 1950s), and there was a plethora of talented people (directors, producers, actors, technicians) who energetically and enthusiastically responded to the challenge. At the beginning of this era of theater on television, the repertoire was composed of classic favorites and well-known plays: “In their early days both media [radio and TV] were more remarkable for familiarizing a mass audience with established plays and authors than for presenting original work” (Knight [1983] 1995, 525). However, from the mid-1950s, the mood of the times not only in theater but also in literature and film was to explore the lives of common people. The revolutionary approach was to shift the focus from the dining room to the kitchen and from the genteel neighborhoods of the middle classes to the districts of the working class.

With the arrival of commercial television in Britain in 1955, drama widened its appeal to more segments of British society. ITV included plays in its schedule from the very beginning, and one of its regional franchises, Granada Television, stood out for the quality of its drama, documentaries, and other programs of social interest: “It had a northern, left-wing, progressive agenda.”1 Armchair Theatre (1956–69) was ITV’s first major contribution to the development of the single play, adopting the new trend of depicting ordinary lives. Young authors “jumped at the opportunity offered by the ITV companies, who were in desperate need of writers to help fill the schedules. In this way ITV made a major contribution to the growth of television drama in the late 1950s, not just in developing new drama series and serials, but in commissioning new writers for the more prestigious single play” (Cooke 2003, 37). It should be noted that those involved in the production of independent television were learning their trade as they went along. In addition, the appearance of their programs would soon be followed by a huge increase in the number of families who were becoming more affluent and who would thus have bought a television set. Television, then, had the aura of being a truly democratic medium. None other than Sidney Bernstein, founder of Granada Television, specifically instructed those eager young professionals to appeal to a wide social spectrum: “He said that now we were up here in the north it mattered very little if our work was praised by the New Statesman critic or not. We shouldn’t feel satisfied if we had just produced a programme that we knew would be praised by the cultural section of the community. There was no special value in doing productions for people who were already converted. It was the others who were important” (Whatham 2003, 54).

Margaret Drabble aptly summarizes the connection between TV and the ideals of the welfare state in her novel The Radiant Way ([1987] 1988). Charles Headleand, the husband of one of the three protagonists, belongs to the generation of inexperienced graduates who make adventurous, exciting television in the late 1950s and early 1960s, with the enthusiasm of pioneers conquering a recently discovered territory. That at least is how he remembers those early days in the novel:

The Brave New World, it would be, and the new populist and popular medium of television would help to bring it into being. The team itself, with its mixed skills, its mixed social origins, its camaraderie, its common purpose, was a microcosm of what would come about: a forward-looking, forward-moving, dynamic society, full of opportunity, co-operative, classless. . . . Sound technician sat down with producer, graduate with van driver, artist with engineer. The nation would demand better and better schools, better welfare, better houses, better hospitals, more maternity leave, more nursery schools, more theatres, more swimming pools, more paternity leave, and everything would get better and better all the time. (Drabble [1987] 1988, 176)

It was Granada that would create the best-known soap opera in the history of British television, Coronation Street (which began in 1960 and is still running), with a strong bias toward a realistic depiction of the working class and fully informed by the aesthetics of the time: “In its iconography, character types and storylines, Coronation Street tapped into the new mode of social realism, or ‘kitchen sink’ drama, that had been popularized in the theatre, and in literature, since the mid-1950s, and which was also emerging in the ‘new wave’ of British cinema, and in Armchair Theatre plays . . ., at the end of the 1950s” (Cooke 2003, 33–34). Richard Everitt, one of those pioneers mentioned earlier, was floor manager on the first episode of Coronation Street and would later act as producer of the series. He was one of those who saw the need to commission plays from young writers, as he did, for instance, with The Fat Woman’s Joke by Fay Weldon in 1966. Another important figure in television in those early years was Claude Whatham, “an arch-example of the bold, tackle-anything television directors and producers discovered by the infant programme companies when commercial television was hustled on to the air in 1955–56” (Purser 2008). Whatham played an important part in the development of a series of plays for television broadcast in 1961 called The Younger Generation, in which emerging writers such as Adrian Mitchell, Maureen Duffy, and Robert Holles were given the opportunity to develop their creative talents by writing one-hour plays.

It was, therefore, nothing extraordinary that a new series with the title It’s a Woman’s World was created by the group of professionals working at Granada Television. This new production followed a pattern that had already proved successful: it had a naturalistic style; it contained recognizable characters; and it presented the characters in ordinary situations. The producer for the series was Richard Everitt, and he introduced the novelty in television of presenting fiction that centered on female experience (in radio, Woman’s Hour, a magazine program addressed to women, had existed since 1946): “We felt women were being ignored in television plays,” Everitt stated. “This is their chance to have their say—even if it is all about men” (quoted in Britmovie [1964] n.d.). He commissioned the writing of a fifty-five-minute episode from each of four writers. The idea was to re-create the lives of modern women at different ages. Thus, Dennis Woolf wrote episode 1, Virginia, about an eighteen-year-old; Margaret Drabble wrote episode 2, Laura, about a twenty-two-year-old young mother; Anthony Linter wrote episode 3, Julie, about a twenty-eight-year-old newspaper columnist; and, finally, Norman Crisp wrote episode 4, Jean, about a thirty-five-year-old supervisor in a chain store. Four different directors were in charge of making the plays, Claude Whatham in the case of Laura. The four episodes were broadcast on consecutive Friday nights in September 1964 (Drabble’s play was shown on September 11), and they had no far-reaching impact, being examples of well-made, conventional television drama of their day. Drabble had written her piece in the spring of 1964, when she was still living in Stratford, where her husband worked at the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC). She had just published a very good first novel, A Summer Bird-Cage (1963), and was considered part of the cutting-edge, emerging talent in British fiction. Thanks to her work as an actress, abandoned early on for a literary career, she was acquainted with directors and members of the acting profession. Patricia England, who played the main role in Laura, was a friend of Drabble’s, and England’s husband, Gareth Morgan, was another actor working at the RSC who later became a director with Granada.2

Perhaps the most striking feature of It’s a Woman’s World is that although it presented itself as a series that represented and spoke for women, it was written mostly by men, Drabble being the only female writer. The same can be said of another representative TV drama of the mid-1960s, The Wednesday Play, a series that enjoyed the favor of women viewers but that was written mostly by men: “Given the fact of male authorship and this apparently majoritative female viewership, the relationship between viewer and image begins to be one of the female audience as passive recipient of the male message-system” (Macmurraugh-Kavanagh 2014, 193). It is in fact difficult to avoid the feeling, when one reads the plotlines of It’s a Woman’s World as announced in TV Times, that although the episodes focused on female characters, the prevailing point of view was masculine. The protagonists of the male-authored episodes, for instance, were built on stereotypes. Virginia deals with the figure of a pretty and vain girl whose only concern is to attract the boys’ attention. Julie is portrayed as a brilliant, beautiful, and rich newspaper columnist who nevertheless “is conscious of having missed something on the way to becoming a success” (TV Times 1964a). Meanwhile, the protagonist of the last episode, Jean, is “patently good at her job” in the department store, but, according to the play bill, she “is by no means dedicated to it. Like the great majority of women Jean would rather be married” (TV Times 1964b). The conceited young woman, the ruthless professional, and the spinster were the three models re-created in the plays written by men for the series. Drabble, however, presented in her depiction of Laura a real character torn with contradictions, a depressed mother and bored housewife who is vulnerable but also firm, proud but also miserable, frustrated but also fully aware of her obligations. Drabble remembers the play in the following terms: “It probably was a self-conscious kitchen-sink, feminist play, but written very close to the experiences Pat [Patricia England] and I knew well—of trying to organize a life and a career round small children. Re-reading it, the mother seems very cross and grumpy, but I don’t think we were like that at the time. I remember more laughter than complaints.”3

Laura tackles a day in the life of a middle-class, educated woman (she holds a bachelor of arts degree) who has become a mother recently and devotes most of her time attending to the dull tasks of caring for home and baby: “Ten to eleven, sit and look at myself in the mirror. Eleven to twelve, feed that baby. Twelve to one, think about what to eat for lunch. One to two, eat it. Two to three to four to five and so on and so on and so on” (p. 10). The lack of punctuation indicates the automatism and listlessness of her everyday tasks. Drabble offers the portrait of a dysfunctional mother and wife with the explicit intention of detaching her character from the archetypal English housewife of the 1960s. Laura has sleeping problems and dietary issues, probably as a consequence of her humdrum routine, and as with Jane in Drabble’s novel The Waterfall (1969), her distress is taken to the level of a schizoid disconnection from reality, epitomized in her tantalized soliloquies, especially when she talks to herself in front of the mirror. In a Lacanian mirror stage, Laura recognizes and unrecognizes herself throughout the play. The completeness she feels after kissing her image in the mirror when she is getting ready to go out for dinner results in the illusion of a complete subject, but it is no more than an imaginary and fraudulent figure, one that does not belong to her and that turns her again to the initial stage of listlessness. The subtext of Laura might serve to represent the middle-class anxiety provoked by the social and political unrest of the 1960s; “several commentators detect a sense of national schizophrenia during these years, potentially caused by Britain’s ambiguous post-imperial situation and exacerbated by widespread (relative) affluence pitched against anxieties focused on the direction in which society seemed to be moving” (Thumin 2002, 150). The new consumer society within the welfare state is represented by many details, such as the figure of the health visitor and the medical controls provided for newborns, different commodities and luxury items, the act of taking a taxi or going out for dinner, and, as discussed later, the old friend Caroline’s hat.

The first act begins at ten o’clock in the morning when Laura is dismayed at the day ahead, during which she knows she will talk to no one until her husband returns from work in the evening. Taking care of the baby and washing nappies will be, she imagines, her only activities. However, Caroline phones and announces her visit, which is arranged for later in the afternoon. The morning proves to be busy, contrary to Laura’s expectations, as she has encounters with both the milkman and a salesman. A fade to black indicates a gap in time, and the scene continues at four o’clock in the afternoon, when the health visitor arrives, followed some time later by Caroline, marking the end of act 1. The health visitor and Laura’s old friend Caroline seem to embody opposed spheres. At one end of the spectrum, the health visitor’s attitude personifies British traditional female values that exalt motherhood as the center of women’s lives and that make Laura feel diminished for not considering herself an exemplary mother. Patriarchal society was slowly beginning to crumble at the time, and this fragmentation had begun to be reflected in the arts by the representation of women characters who did not fit standard classifications. At the other end of the spectrum, Caroline, free of the yoke of motherhood, epitomizes the idealization of the emergent female role in Britain: a cosmopolitan woman who follows fashion, is well educated, travels, and has access to contraception, thus to a freer sexuality. Caroline objectifies motherhood by referring to the baby with the gender-neutral pronoun it, which is grammatically correct but which also indicates how obscure and distant the baby is as a concept for her. It eventually seems that Laura is living in an impasse between these two models, which inevitably provokes her distress in that she finds herself in “physical and emotional situations for which there are no literary guidelines” (Cooper-Clark [1980] 1985, 22). As a consequence, the impression of Laura as a volatile character is reinforced by the visit of these two opposing characters, the health visitor and Caroline.

Act 2 covers the rest of the afternoon. Laura and Caroline have just had a cup of tea and engage in conversation, Laura’s frustration with her life being the main topic. Sometime later Bill arrives home from work and is pleasantly surprised to find Caroline there. The character of Bill corresponds to the image of the absent father, and through the rest of the play he does not seem to care much about the newborn baby. In Drabble’s novels, “men are depicted as absent or negligent fathers, [and] both the burden and the ethical reward of parenting are assigned to women” (Rose 1985, 6). It is here that the most disruptive element of the plot is introduced, the proposal that the three of them go out for a meal that evening. Act 2 finishes with expectations high on this ephemeral promise of freedom: the resolution will form the conclusion of the play in the following act.

It is shortly before eight in the evening when act 3 begins and the characters are getting ready to go out. Bill, however, has not managed to find a babysitter, and the option of having an evening out is thwarted. Bill offers to take care of the baby so that Laura and Caroline can enjoy some time in the restaurant, a suggestion that both women veto; then Caroline volunteers so that the married couple can have some time for themselves out of the house. The baby’s needs will impose themselves in the end, however, and in fact it is Laura who finally stays at home while Bill and Caroline go out. The opposing love–hate nature of motherhood is clear in the final scene, in which Laura hugs the teddy bear with tenderness after punching it furiously. Motherhood is thus represented as both the agent of destruction and the force for personal fulfilment. Drabble has recognized the recurrent use of opposed concerns in her literary work: “Every person is full of such contradictory patterns, inevitably. But my characters seem to have got just enough force in them to stick together” (in Hardin 1973, 282).

The style of the play follows conventional models and continues the tradition started in the 1950s when “it was believed that naturalism was the style for television drama” (Brandt 1981, 24). The original title of the play, These Four Walls, refers eloquently to the atmosphere that can be expected in the piece. It was probably changed to Laura as part of the process of homogenizing the four episodes. The setting, a number of rooms that re-create those of a suburban house, had to invoke familiarity. Such elements as an unmade bed, an untidy living room, and a kitchen where an assortment of nappies are hanging on a line would remind viewers of the house of a woman who is not coping well with enforced domesticity. The rooms where the action occurs are basically the kitchen, the living room, and the bedroom, although over the course of the action other parts of the house are visited, such as the bathroom, the landing, and the hall. Apart from the setting, the approach to time in the play is also easily assimilated by viewers; the fifty-five minutes of the program correspond to ten hours in a day in the life of Laura Stephens, which, according to film and televised fiction standards, is a pace that equates quite closely to a natural depiction of real life.

Concerning the symbols in the play, the baby of course represents the physical evidence of Laura’s stage in life, the conclusive proof that she has entered a new domain, having left behind the carefree attitudes of the young. It has to be said that the baby is never shown; this is not for any obscure reason but rather owing to technical problems in production. Drabble had to adapt to the constraints of the new medium, although she was “disconcerted that we weren’t allowed to show a real baby on screen—if I remember rightly the baby was always off-screen, and in the closing scene Laura is shown hugging a huge teddy bear, which I thought was ridiculous.”4

The first connection that comes to the viewer’s mind is John Osborne’s symbology in his seminal work Look Back in Anger (premiered in 1956, published in 1957): in particular the bear–squirrel game played by Jimmy and Alison. The symbology of these two elements in Look Back in Anger became so powerful among the British collective imagination that a few years after the play’s performance, according to Osborne, “whole pages of respectable national newspapers would be devoted to Valentine’s Day messages from ‘Snuggly Bouffle Bears’ to ‘Squiggly Whiffly Squirrels,’ far more nauseous than my own prescient invention” (Osborne 1994, 47).

The bear and the squirrel have usually been understood as the representation of the only space in which Jimmy and Alison, these “timid animals,” can share their love and be isolated from the outer world and from any “cruel steel traps lying about everywhere” (Osborne 1957, 96). These two elements, also present throughout the whole play as the furry animals sitting on a shelf in the living room, are a constant reminder of the unreal dimension of Alison and Jimmy’s relationship, the only one that seems possible, located in the “bear’s cave” and the “squirrel’s drey.” This imaginary safe place in their marriage allows them to forget their past mistakes and their flaws, and only by pretending to be their alter egos “can they relate to one another without misunderstandings” (Pattie 2012, 154). Considering that Jimmy and Alison cannot escape the unpleasant results of their circumstances and decisions throughout the play—that is, the “double-bind theory” proposed by Luc Gilleman (2011)—we are left with the feeling at the end of the last scene that their safety might be only provisional, that there will not be a happy or even pleasing ending, and that the prosperity of their relationship must therefore “be spiritual if it is to exist at all” (Ditsky 1977, 73).

In Laura, the teddy bear brought by Caroline in act 2 could be interpreted as an allusion to maternity. The teddy bear does not appear again until the final scene, in which the protagonist is left alone at home again, watching television and eating chocolate. Laura takes the bear, furiously punches it in the stomach, and calls it “stupid baby,” which would reinforce the sense of frustration she derived from her role as a mother and housewife. However, when the teddy bear responds with the words “mummy, mummy” (p. 48), Laura feels deeply moved, and so, with tears in her eyes, she holds the bear. It seems that she ultimately embraces maternity and loves her baby in spite of how limited her life has become. The play’s denouement exposes how Laura, like Alison and Jimmy, embraces her fate in the face of all the threats and dysfunctionalities of her marriage, although the reader or viewer is left again with a sense of transience.

Despite this apparently manifest connection between Osborne’s play and Laura, something that the director and the producer of Drabble’s play were probably aware of, the truth is that Drabble resisted the inclusion of a teddy bear as the replacement for a real baby; she wanted to have the baby on the screen, but this option was finally rejected. The use of the teddy bear was for Drabble a sentimental device; her wanting the real baby at the end of the play reveals her desire for realism and for embracing life without intermediaries or symbols.

Finally, another symbol included in the play is Caroline’s hat, which, contrary to the symbol of the baby, represents the life Laura has lost through getting married and serves as a catalyst for her aim to regain her independence. It is highly significant that when she puts the hat on, the baby starts to cry, reminding her that she is no longer able to recover this former life. And when Laura sits on the hat in the final scene, she is graphically squashing the promises of individual freedom that Caroline’s visit has brought with it.

The innovation of the play, then, does not reside in any technical aspects in the structure of the narration. The play is instead thematically far from conventional, though following the usual patterns of the televised drama of the time: Drabble was able to create a multifaceted character who escaped being classified as a clear-cut stereotype. Through her protagonist, she voiced her opinion as an intellectual woman writer who was fully immersed in a number of current issues. In Laura, Drabble expressed her concerns regarding the state’s intrusion in the individual’s life, the banality of the media, the wide gap between women’s aspirations and reality, the false security of a well-ordered existence, and—one of the classic topics of her fiction—the force of fate in an individual’s life, represented by the final image of the protagonist, alone at home, just as the spectator first sees her at the beginning of the play.

Works Cited

Brandt, George W. 1981. British Television Drama. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Britmovie. [1964] n.d. Excerpt from TV Times, Aug. 28. At filmdope.com/forums/107466-julie-samuel.html.

Cooke, Lez. 2003. British Television Drama: A History. London: British Film Institute.

Cooper-Clark, Diana. [1980] 1985. “Margaret Drabble: Cautious Feminist.” Atlantic Monthly, Nov. Reprinted in Critical Essays on Margaret Drabble, edited by Ellen Cronan Rose, 19–30. Boston: G. K. Hall.

Ditsky, John. 1977. “Jimmy Porter and the Gospel of Commitment.” ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature 8, no. 2: 71–84.

Drabble, Margaret. [1969] 1971. The Waterfall. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

————. [1987] 1988. The Radiant Way. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Gilleman, Luc M. 2011. “The Logic of Anger and Despair: A Pragmatic Approach to John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger.” In John Osborne: A Casebook, edited by Patricia D. Denison, 71–90. New York: Routledge.

Hallam, Julia. 2003. Introduction to Granada Television: The First Generation, edited by John Finch, 1–24. Manchester: Manchester Univ. Press.

Hardin, Nancy S. 1973. “An Interview with Margaret Drabble.” Contemporary Literature 14, no. 3 (Summer): 273–95.

Knight, Roger. [1983] 1995. “Broadcast Drama.” In The New Pelican Guide to English Literature, vol. 8: From Orwell to Naipaul, edited by Boris Ford, 522–30. London: Penguin.

Macmurraugh-Kavanagh, Madeleine. 2014. “Too Secret for Words: Coded Dissent in Female-Authored Wednesday Plays.” In British Television Drama: Past, Present, and Future, edited by Jonathan Bignell and Stephen Lacey, 191–202. Houndmills, UK: Palgrave.

Osborne, John. 1957. Look Back in Anger. London: Faber and Faber.

————. 1994. Damn You, England: Collected Prose. London: Faber and Faber.

Pattie, David. 2012. Modern British Playwriting: The 1950s. Voices, Documents, New Interpretations. London: Bloomsbury.

Purser, Philip. 2008. “Claude Whatham: Obituary.” Guardian, Jan. 1. At http://www.theguardian.com/media/2008/jan/10/television.culture.

Richardson, Tony. 1993. The Long-Distance Runner: A Memoir. New York: William Morrow.

Rose, Ellen Cronan. 1985. Introduction to Critical Essays on Margaret Drabble, edited by Ellen Cronan Rose, 1–18. Boston: G. K. Hall.

Thumin, Janet. 2002. Small Screens, Big Ideas: Television in the 1950s. London: Tauris.

TV Times. 1964a. “Play Bill” (unsigned), Sept. 11. At https://Radiosoundsfamiliar.com/the-tv-times-archive-1960s.php.

————. 1964b. “Play Bill” (unsigned), Sept. 18. At https://Radiosoundsfamiliar.com/the-tv-times-archive-1960s.php.

Whatham, Claude. 2003. “Door-to-Door Salesmen.” In Granada Television: The First Generation, edited by John Finch, 54–55. Manchester: Manchester Univ. Press.

1. Margaret Drabble, unpublished comments on her plays, 2012, document sent by Drabble to José Francisco Fernández.

2. Drabble, unpublished comments on her plays, 2012.

3. Drabble, unpublished comments on her plays, 2012.

4. Drabble, unpublished comments on her plays, 2012.