The heathland around Horsell in Surrey where I grew up always terrified and excited me in equal measure. H.G. Wells set his War of the Worlds there on the outskirts of Woking and I could never put that out of my mind as a child. I thought the expanse of sandy ground, which encouraged little but heather and bracken and conifers to grow, was an obvious location for Martians to land and inflict defeat and suffering on the world. It made for a surprising and occasionally frightening playground, hundreds of acres of rough scrub and dense wood to explore, full of strange, incongruous spaces.

Once, when my brother and I had roamed a little further than usual, we’d come across a dilapidated walled enclosure deep within a grove of pine trees. It was as if we’d discovered the remnants of an ancient city. The oriental domed entrance gate and brick walls exuded a ghostly presence. We’d skirted its borders but hadn’t dared enter. Only later did I find out it was the burial ground for a handful of Muslim Indian troops who’d died of their wounds from fighting in France during World War I (with a few other casualties of the Second World War added in the 1940s). Their bodies had been shipped from an army hospital in Brighton. Over the years, disrespect had replaced honour and locals had vandalised the site, causing the bodies to be moved to a different cemetery. The place had become derelict.

I imagined Lüneburg Heath would have the same disquieting quality. But none of that dark and lonely aspect manifested itself as I drove across it. It was a pleasant, cool, bland region of inoffensive farmland and woods and low hills of heather. Stretching from Hamburg in the north of Lower Saxony to Hannover in the south, the landscape was mostly flat and innocuous.

On the route from Hamburg to Bergen-Belsen, the first concentration camp liberated by the British, I stopped at the Commonwealth War Cemetery at Becklingen. It felt an appropriate thing to do. The graveyard was tight against the roadside of the B3, an isolated place, unheralded and unanticipated when it suddenly appeared on my right with its lines of white headstones covering a slightly inclined plot surrounded by a thick hedge.

The perfectly maintained cemetery housed the graves of over 2,000 British casualties. The inscriptions were, as in every British cemetery of the Second World War, pitiable. Many were generic, I assume chosen from a list supplied by the stonemasons, but occasionally with a glimpse of something more personal. Those are the ones that make you weep.

As I walked the lines of graves I noticed how many had died in the last months of the war. I tried to imagine the pain of the families. Would it have been more acute when news of the surrender of German forces came through? They must have been ripped apart by the thought that their son, father, brother, husband had been within a few days of surviving the conflict. Gunner Alcock, for instance, who’d died on 1 May 1945. Or Lance Bombadier Booker, killed on 4 May. Or my namesake, Private Williams of the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry, aged nineteen, on 25 April. So close to making it through. And so young too.

The weight of numbers killed in those few weeks remains testimony to the bloody fighting that had to be done right up until the end of the war. Though the British moved swiftly across this country, they still encountered occasional fierce resistance. They expected it. Swathes of troops may have been capitulating across the front, but many instances of brutal struggle occurred.1 They induced intense caution and fear that the German forces would mount some kind of counter-attack or stand to the last man even though all was palpably lost. That was the presumption given the rabid pronouncements coming from the Nazi leadership even after the death of Adolf Hitler was relayed from Berlin on 1 May.

If confirmation was needed that the British were fighting an implacable foe, they found it several miles along the road from Becklingen Cemetery, across the heath towards Hannover, at Bergen-Belsen. They arrived in the town in April 1945 to encounter a huge concentration camp that would unman even the most battle-hardened of soldiers.

A bank of pine trees obscured the entrance to the camp on a bend of the L298 road a mile south of the British Army base still used as a tank firing range, but I caught sight of the discreet sign in time. I felt a tremor of discomfort when I pulled into the coach park full of school outings from across Europe. ‘It’s a theme park,’ I thought to myself. ‘A bitter and sickening theme park, but a theme park nonetheless.’

I knew this was irrational, if not wrong: wrong for me to think like that and wrong in fact. If the place had been erased and given no memorial I would have been angry at the suppression of history, the failure of the German nation to acknowledge its past. At least by making the camp accessible, free to enter and a destination for commemoration, due remembrance was and may remain possible.

But the frisson of distaste wouldn’t go away. Maybe it was the cafeteria in the basement of the modern white concrete building that exuded architectural merit and housed the exhibition and documentation centre. Though no doubt artfully designed, tasteful, the sight of the café somehow made me bad-tempered. I thought: how could you eat here, beneath those pictures and artefacts and recordings in the exhibition floors above? How could you sit down and have a peaceful cup of coffee, a cake, a snack to alleviate a slight feeling of mid-morning hunger knowing those who’d been incarcerated here had suffered such deprivation of food and drink that they’d been driven mad, mad enough to claw the soil for any scrap of edible matter, mad enough to cut the flesh from a corpse and shove it into their mouths to chew raw? Then there were all the things you could buy in the bookshop: DVDs as well as publications and leaflets. If this were anywhere else, signs advertising ‘gifts’ and ‘souvenirs’, key rings, postcards and inscribed trinkets would hang on the walls and counters. I wondered how long it would be before that happened, the transformation of shrine into tourist attraction.

Mine was a ridiculous response. Of course it was. I reminded myself that even those who came to mourn had to eat. And buying books recounting the history of the camp and some of those who’d survived, which I’d done on many occasions, was important: keeping the past relevant and known and knowable. How easily it could slip into obscurity otherwise.

The logic didn’t dispel the unease. It made me ask yet again: why visit these places? Was it macabre? Morbid and slightly odd? At the time I travelled to Lüneburg Heath and Bergen-Belsen, I was in the midst of examining more allegations against British forces during their occupation of Iraq after 2003. Hundreds were emerging. Invariably these mentioned military camps, places where detainees were held en masse for the purpose of interrogation. I’d read many victims’ statements about their treatment in the army bases, camps like Abu Naji and Bucca and Shaibah, where techniques were used to break men down and reduce them to nothing, to numbers, sometimes to playthings. That was what the statements conveyed, though I couldn’t vouch for the truth or falsity of any of them. And, of course, this was all in the shadow of the new ‘camp’ imagery from Guantanamo Bay and those ‘black sites’ condemned as destinations for victims of ‘extraordinary rendition’. Wasn’t that the reincarnation of the KZ idea, at least as regards its purpose in isolating, corralling, dehumanising and slowly shredding a body of its living qualities? Orange jumpsuits instead of striped pyjamas? Waterboarding instead of whatever torture one can imagine the Nazis practised? The comparison was trite, perhaps, but founded on a truth: the institutionalised breaking of a person’s mind and body through a regimen of psychologically and physically inflicted pain was central to both. What touches in these places is not the deaths but the lives; stripped to the bone, to bare life. What possible reason could there be to do that? None. But some excuse is always found: you pose a threat to security; you’re contagious; you’re different. It never seems to take long before a reason justifies anything.

I was sick of it all, of reading about ill-treatment and torture, but I couldn’t turn away and forget. Maybe the journeys to the past and to Germany were a substitute for those inaccessible sites in Iraq, a safer way of trying to gain some insight as to how a place, a ‘camp’, can induce the degradation of humanity in guard and inmate alike. But I also thought of another reason: if I didn’t go, all my knowledge and understanding would be limited to literature or text. I was convinced that to touch the ground and smell the air, to walk amongst the buildings was necessary to gain a better sense of the atrocity that Nazi Germany had perpetrated. The experience might not communicate the raw suffering and boredom and moments of hope and ordinariness, the life and lives of the camp despite the prevalence of death (for whatever their nature, lives were led here, people did survive though in a state of decomposition of spirit and personality and body), but it might reveal something intangibly vital nonetheless. The chance of achieving some awareness was worth the danger of morbid fascination. I convinced myself it didn’t matter who else was walking about the ruins, what their motivations were, how they felt. Every visitor had their own reasons for making the effort. That was their affair.

It helped that Bergen-Belsen has been preserved in good order as a memorial, a Gedenkstätte, without ostentation. Once through its gates, past the motley group of buildings both modern (to house the exhibitions) and original, you enter a great expanse of scrub and grass, surrounded by tall birches and conifers, and dissected by roughly bordered pathways curling around landmarks. Plinths and signboards indicate where barracks and crematoria and the hospital and other buildings used to sit (most were burned down by the British to stop disease spreading). Others are simple memorials: a small headstone for sisters Anne and Margot Frank, who died of typhus here; a tall concrete obelisk backed by a wall with inscriptions in various languages remembering the dead from numerous countries; a thick pedestal erected by the Central Jewish Committee in 1946 recording the deaths of thirty thousand Jews ‘exterminated at the hands of the murderous Nazis’ screaming its anger with capital letters and an exclamation mark: ‘EARTH CONCEAL NOT THE BLOOD SHED ON THEE!’

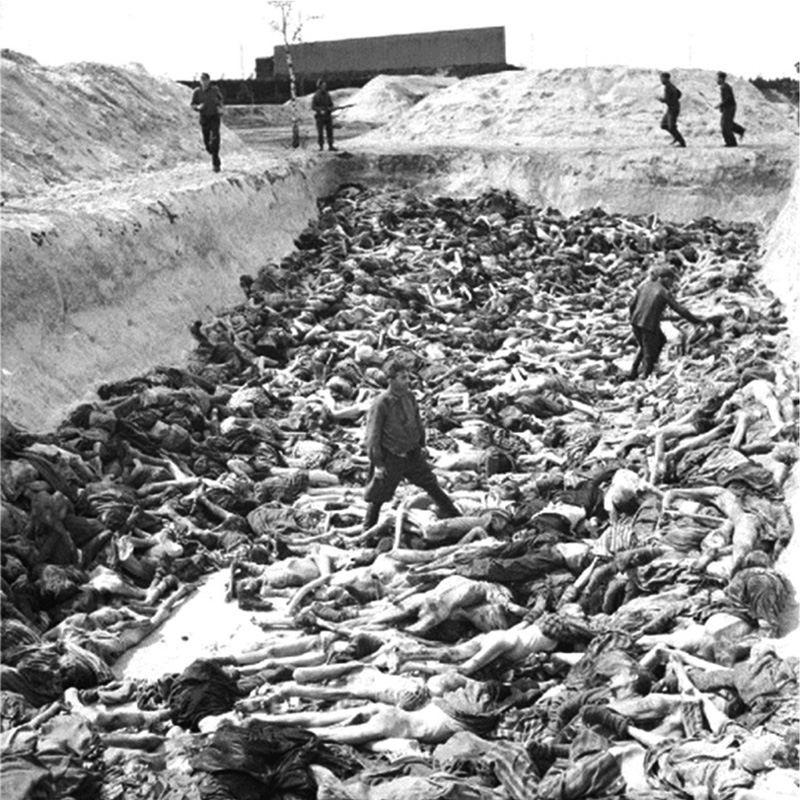

The mass graves were marked too. The bodies, pushed and thrown into vast pits, had to be covered quickly to stop the typhus spreading. Large stone plaques now rested on the side of compacted, rectangular mounds of earth. They recorded the number of people buried beneath, 1,000 and 2,500, like grim denomination bills. That was the scale of death in the camp at the end of, and just after, the war. They simply recorded the figures and said nothing about those who’d died.

It was tempting to be drawn in by the numbers. If said with authority their effect can be disconcerting. Five thousand, twenty thousand, a hundred thousand, six million: they quickly become symbols of something other than the individuals they’re supposed to represent. They say more about the perpetrator than the victims, who dissolve collectively into unknowable fractions. Then it isn’t long before the numbers are set as indicators against which other atrocities are measured. A ghoulish competition can erupt, the greater the quantity the more dreadful the deed, perhaps.

A little while ago I gave a reading at a book festival of A Very British Killing, the book I’d written about one case of ill-treatment of several Iraqi detainees. I spoke about the details of Baha Mousa’s death, the man killed by British troops in an army base in Basra in September 2003. At the end of my talk someone said he’d read the book and was a little disappointed. He thought there would have been more revelations about torture and brutality. Quickly worried that the rest of the audience would misunderstand him (or it seemed to me), he said he didn’t mean he wanted to see more cruelty. It was just that what happened didn’t feel that … that terrible. Bad, yes. Of course. But not horrific like the Nazis, if I knew what he meant. In the vacuum of my silence he carried on: we hear of so many deaths and atrocities these days, don’t we? One death seems … well, a little insignificant.

I asked the man, how many does it take before we get angry and do something? He shrugged. He couldn’t say. In fairness to him, it was a hackneyed question of mine. I worried, though, that the man’s comments echoed many people’s views. Not that anyone else would voice them easily. They might be misinterpreted: how callous to support the idea that one death should count for little, should be incapable of provoking shock or concern?

Walking along those meandering paths of the Bergen-Belsen site I thought that the numbers carved into the stone laid on the mounds were callous too, albeit unintentionally so. I didn’t believe that they contained 1,000 or 2,500 people exactly. I didn’t believe that those who had to bury them counted and stopped at the exact figure and then filled in the grave. I thought they must have guessed, made a rough estimate, rounded up or rounded down, that it didn’t matter whether it was 999 or 1,001 or some other figure around the thousand or whatever figure they ended up carving into the stone. The number was vast, signified by the multiple noughts. That was enough.

Do the mathematics of war crimes matter? Politically, legally, it would seem so. Arguments about the number of Jews killed in the Holocaust have never ceased since the initial investigations immediately after the war. In February 2006, as if oblivious to the moral ambiguity that equates quantity to seriousness, Luis Moreno Ocampo, then Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, responded to hundreds of written submissions he’d received (one of them related in part to Baha Mousa) about allegations of unlawful killings and war crimes committed during the British invasion and occupation of Iraq.2 He wrote that ‘while, in a general sense, any crime within the jurisdiction of the Court is “grave”’, no case would be investigated by his office unless it passed ‘an additional threshold of gravity’. The criteria couldn’t be expressed scientifically, but a ‘key consideration’, he said, was ‘the number of victims of particularly serious crimes, such as wilful killing or rape’. For Iraq this ‘was of a different order than the number of victims found in other situations under investigation’ by him. He mentioned the Congo and Darfur, that featured, he said, ‘hundreds or thousands of such crimes’. Four or five or twelve killings were insufficient for his office to do anything. He wouldn’t sanction any further action until such time as evidence of more allegations came to light, if they ever did.

There were no such difficulties when British troops entered Bergen-Belsen in April 1945 and encountered the mounds of bodies, the scattered corpses, the thousands upon thousands of dying or barely living. Some of the soldiers may have been conscious of the concentration camps from all those news reports before and during the war. But could any of them have believed they were this terrible? From the accounts of the liberation, I didn’t think so. I didn’t think they were prepared, any more than the politicians and government officials were prepared when they were calling for retribution from the comfort of Whitehall.

The news filtered through slowly. On 14 April 1945, amidst the general communiqué of battle success across Germany, The Times reported: ‘British troops will soon be facing the problem of dealing with a big German concentration camp in their line of advance at a village called Belsen 10 miles north-west of Celle. Their information is that there are about 60,000 persons in the camp, some of them political offenders, some criminals, and among them are about 1,500 with typhus and 900 with typhoid fever, as well as about 9,000 sick with other complaints.’3

That was all, for the moment: a vaguely expressed fear that recent scenes from Ohrdruf and Buchenwald would be replicated. Even then it was strange language that was used, as though the paper thought it was important that some of the inmates were ‘offenders’ or ‘criminals’, information that could only have come from the Germans.

Unlike most of the camps to be liberated by the Allies, Bergen-Belsen was handed over in a relatively orderly fashion. Its situation was different as it had become the destination of last resort for prisoners transferred from many other camps to the east or south. Already a sinkhole for prisoners from the middle of 1944 onwards, Bergen-Belsen was a place where the sick had been sent, those too ill to work. Some camp prisoners had been told they were being transferred there to ‘recuperate’. It was nothing more than a euphemism for gradual death as there were few if any medical facilities there to aid recovery. A tent camp had had to be constructed in late summer 1944 to cope with the increased numbers. It held 8,000 women transferred from Auschwitz until, in November 1944, a storm destroyed the tents. All the occupants had then to be shifted into the barracks. As Germany collapsed on all fronts, an even greater influx of prisoners arrived during the early spring of 1945, making the already overcrowded conditions in the camp untenable. From 15,000 inmates at the end of 1944, the camp housed over 42,000 by March 1945. No heating, limited food, next to no medical supplies, little shelter and the decay of those barely living caused disease to fester and spread throughout the camp. It was impossible to contain the lice. Dysentery and TB were predictably rife. But it was the onset of typhus that became an immediate and unstoppable killer. In March, 18,000 people died in the camp. Those who remained were surrounded by decomposing corpses. They were given little if any food. Water was scarce.

By the beginning of April, with typhus rampant and British forces moving more quickly than the Germans expected, the German command became terrified by the prospects of having to follow the general order recently emanating from Himmler to prevent concentration camp prisoners falling into the hands of the enemy. Himmler was persuaded to relax his position and the Allies were contacted with a proposal to surrender the camp to their care on 12 April. Some members of the SS administration were to remain with a detachment of Hungarian troops who were already guarding the camp for the Germans. The agreement with the British was that they would stay to continue their duties, although under British control.

Sometime on 15 April the first British soldiers entered the camp. From the moment they stepped through the gates they realised the hellish nature of the place. It may have been called a liberation, but the inmates were not free. Captain Derrick Sington of the Intelligence Corps commanding No. 14 Amplifying Unit (a small fleet of trucks with loudspeakers, used to relay information and commands to the public) was told to drive about the compounds telling everyone that the British had arrived and that no one was allowed to leave.

Many years later, Gerard Mansell, one of the first intelligence officers there, wrote about the environment the British troops had entered. He said that he and his colleagues ‘were utterly unprepared for the scenes which greeted us – the shabby rows of flimsy wooden huts packed with hundreds of the dead and dying, lying heaped on the tiered bunks; the pathetic little knots of listless, skeletal figures with shaven heads, their grimy, striped prison garments hanging loosely from their protruding bones; the deep pits half-full of emaciated, naked corpses; the bodies lying everywhere in hundreds, the living often indistinguishable from the dead; the forlorn heaps of shoes, spectacles and other effects, all that remained of the thousands whose ashes now covered the ground with a fine powder’.4

On 18 April, the senior medical officer of the British unit which had taken control of the camp talked to the press about the conditions he’d found. It was ‘the most horrible, frightful place’, he said.5 And indeed the picture he painted was terrifying. He said ‘there was a pile, between 60 to 80 yards long, 30 yards wide, and four feet high, of the unclothed bodies of women all within sight of several hundred children. Gutters were filled with rotting dead, and men had come to the gutters to die, using the kerbstones as back rests.’ He said that cannibalism had been reported by his men. He said there was no water, turnip soup was all that the Germans had been feeding the inmates, typhus was rampant, but starvation was the main killer. He said he was shown all this and around the enormous compound by the SS commandant, Josef Kramer, who had stayed to surrender the camp to the British. Kramer was described as ‘a typical German brute – a sadistical, heavy-featured Nazi’, who was ‘quite unashamed’.6 There were ‘enormous covered death pits’, but one was exposed: it ‘contained a great pile of blackened and naked bodies’.7 No one had been prepared for these scenes of concentrated carnage.

As part of the relief effort, a medical team was summoned. Some of the doctors were later compelled to write about their observations, to publish professional musings as though they had been suddenly thrust into a horrible experiment. Their articles may have been drafted for a specialist audience, but to me they shone light not only on the treatment that was needed, but also on the lives those in the camps had had to endure.

The British Medical Journal printed a shortened version of Captain Mollison’s report for the British 21st Army Group that then occupied north-west Germany.8 He described the state of a typical survivor whom his team had treated. It was a clinical assessment stripped of emotional rhetoric. Such is the nature of academic medical reference and perhaps more revealing for all that, though the language made me flinch.

The patient lay flat in bed with acute distress, yet with a miserable expression. He showed no interest in anything except his own needs, and appeared completely indifferent to the deaths that occurred so frequently. Moreover, death was a very public affair, since there were no screens and beds were crowded together. He talked with a whining voice and complained continually, usually of his severe diarrhoea. ‘Scheiszerei’ was the commonest word. Second only to this complaint was unfavourable comment on the diet, the soup being blamed for the diarrhoea. Black bread was next in unpopularity. Patients who were a little less ill asked continually for white bread and complained that they were being starved. The truth was that there was enough food in terms of calories, but much of it was unpalatable. Although starving, they were extremely particular about their diet and very difficult to please. Most of them did not fancy sweet things, and almost all wanted solid food rather than soup. When they wanted a drink, lemonade or something sour was most often asked for. They were all sure that soup and cold food made the diarrhoea worse. Although milk was available as an alternative to the full diet, many of the patients didn’t want it, and, if given it, complained that they were not getting enough to support life. Because of their poor appetite, many of them left their food untouched, and as there were insufficient nurses to feed them their state rapidly became worse. The orderly simply put the food beside the bed and left it. Later the untouched food would be collected if the patient had not secreted it in his bedding for future use. Fear of being without food was so great that even dying patients would put bread-and-butter and meat under their pillows.

Mollison’s account cast doubt on the nature of any liberation. For the prisoners, removal of the SS guards didn’t mean escape from their torment. And if food was a problem, more so was bodily function. The minutiae of medical observation, rarely revealed in the sweeping press and courtroom accounts I’d read, exposed the predicament for both victim and medic. Mollison wrote,

All the seriously ill were incontinent of faeces, and their beds were continually soiled as there were not enough orderlies to change them, and, in any case, many of them had no sheets but simply lay on covered palliasses. Almost every patient when first seen had diarrhoea – varying from two to three loose stools a day to an almost continuous production of watery stools. In the latter cases a movement of the bowels invariably followed immediately after taking anything by mouth, so that the patient was afraid to eat or drink. The stools did not as a rule contain blood or pus. They were often light brown in colour, smelt offensive, and consisted of fluid and lumps of undigested food. On examination the patient had an appallingly thin face. The eyes were sunken and the cheek-bones jutted out. These extreme changes made all the patients look alike, so that it became difficult to distinguish one from another. This difficulty was accentuated by the fact that all patients had had the bulk of their hair shaved off. The skin of their arms, legs, and anterior abdominal wall was often rough, dry, and scaly. There were large bed-sores on the buttocks and the lower part of the back. The ribs stuck out, and it was difficult to use a diaphragm type of stethoscope because it simply bridged across two ribs and made no contact with the skin dipping down in between. The anterior abdominal wall was concave, falling away from the ribs above and from the anterior superior iliac spine below. The greatest muscle-wasting was around the pelvis. The ischial tuberosities stood out prominently and the posterior surface of the ilium was almost devoid of muscle. There was a depression below the anterior superior iliac spine, and the skin hung down to the thigh in a fold. The legs were fuller owing to oedema; but this was often confined to the ankles and feet, so that a common appearance was of a leg as thin as a stick with a fat swollen foot on the end of it. The face and hands were pale.

This wasn’t the condition of just a few. Thousands of patients had been similarly affected, their massed misery hard to comprehend. In November 1945, fresh from his experience as part of the Royal Army Medical Corps at the camp, Dr Joseph Lewis delivered a lecture about it. ‘In my Division,’ he said, ‘which had the care of approximately 4,500 cases, we were able to discharge as fit just under 2,000 patients after about two months’ treatment. Sweden very generously agreed to accept our more chronic invalids who were fit to undertake the journey by rail and sea, and all our orphans. We disposed of about 1,500 in this way. At this stage we handed over to a small military unit and moved from Belsen, not without regret, for we realised that we had been privileged to see a clinical sight not easily forgotten.’9

‘Privileged’ wasn’t the most apt word, I thought, but doctors were faced with unique circumstances. What language could do justice to the sights they observed? W. Collis and P. MacClancy reported on three paediatric cases of ‘interest’, as they called them, attempting to communicate the impact on inmates of the conditions in the camp.10 But they betrayed some compassion nonetheless. Apart from detailing the consequences of starvation and disease, they told the story of a young boy they named Z., aged five.

He was admitted to the children’s hospital, Belsen, from the general hospital on the death of his mother. His mother, an Austrian Catholic, died at Belsen of typhus. The father, a Slovak Jew, last heard of in Sachsenhausen, was probably dead. A sister, aged 6, was alive and well in camp. Two other children died in Ravensbrück Lager. Nothing was known of the patient’s past history. On admission he was very emaciated. He lay rolled up in a ball under the bedclothes, moaning, and wouldn’t eat or speak. Examination revealed pleurisy with an effusion on the right side, and some infiltration in the right and the upper zone of the left lung. The temperature was irregular, rising to 101°. Sedimentation rate, 101 mm. first hour (Westergren). Pirquet plus. 10 c.cm. of serous fluid was aspirated to exclude empyema. The child was hand-fed with specially appetizing meals while being talked to in his own language. He was given a high-protein diet with an addition of vitamins and calcium, and at first was kept in a warm room; later he was placed in the open air. After one week he began to talk; after two weeks his appetite returned; and after eight weeks the sedimentation rate was 50 mm. He was then evacuated to Sweden. The latest report states that he has put on 7 lb. (3.2 kg.) and is now almost well.

The doctors commented, ‘The above case illustrates the final problem of the Belsen children. It is a social one of the most profound complexity. Here we have a little boy of 5, together with his sister of 6, whose parents have been cruelly murdered and whose family and home have been destroyed. What is to become of him? Is he to be brought up Jew or Catholic? Is he to be left in an orphanage? He has found a temporary refuge in Sweden, but what of the future?’ They offered no answers.

The psychological impact of the camps was studied by another army medic, Captain M. Niremberski. He published an article in 1946 concluding:

Psychiatric study of the most affected of the 60,000 inmates of the Belsen concentration camp showed a concentration camp mentality: a dulling of social adaptation with depreciation of family ties and sense of values, low standard of bodily habits, and aggressive and masochistic tendencies. Terror and fear symptoms were common; memory for remote events was impaired. Passive types showed a marked reduction in activity, even up to complete immobility in some cases. Greatly exaggerated sexual appetites were noted. Young children, up to 8 years of age, showed no marked disorders, but older children showed fear reactions.11

When the British entered Bergen-Belsen they placed under arrest SS camp commandant Josef Kramer, SS Dr Fritz Klein and the rest of the SS detachment who’d been left behind. There was confusion about what should be done with them. Brigadier Glyn Hughes, Deputy Director of Medical Services for the British 2nd Army, said he and Lt Col Taylor, the commanding officer of the British unit which had assumed control of the camp administration, were with Josef Kramer when they heard shots coming from the western end of the men’s section. They all headed to the crematorium, where they found a stack of straw covered with potato plants. Hughes said, ‘A number of male internees were foraging in the stack for food. Surrounding them were three or four individual members of the SS guards of the camp armed with automatic weapons … As I approached the spot I saw and heard them firing single shots at the aforesaid internees and they made no attempt to cease firing when I came up to them, Josef Kramer made no attempt to prevent them or to interfere.’ That the SS guards were still armed was surprising enough. That they should have been allowed to continue to act as ruthless guards even after this incident was incredible. Hughes said, ‘We gave immediate orders to Kramer that all shooting at internees was to cease immediately and that any further case reported to us would result in one SS guard being shot for every internee killed.’12

Whether or not Hughes’s threat was carried out is unclear: he admitted that more shootings by the SS occurred that day and some spontaneous retribution was inflicted. Gerard Mansell would recount much later that Kramer ‘was severely beaten up as he was being taken away’. He said some ‘guards were shot out of hand on one pretext or another. The rest were made to bury the dead and clean up the camp.’

The Daily Mail’s correspondent Edwin Tetlow, accompanying the British Army liberators, wrote that ‘[w]e decided to give the awful task of burial to some of the SS guards and women SS’.13 It was becoming a standard form of ad hoc punishment by the British and Americans. Leslie Hardman, a Jewish chaplain stationed in nearby Celle, was sent to the camp and later described the scene. I found his memoir by chance in my university library. He’d written: ‘I went up to the officer in charge of the burial operations. Two SS men were working under his instructions. As the corpses were pushed to the edge of the pit, they took what bodies they could grasp – bodies interlocked, coagulated, disintegrated – and threw them into the huge open wound which was to be the common grave.’14

The immediate reckoning hadn’t ended there. Tetlow reported, ‘When our troops went into the cells in which these ghouls are being kept they found that one SS man had hanged himself. Two others have now committed suicide by trying to run away.’15 It was an odd turn of phrase. Tetlow explained, ‘They knew they would be shot by our men if they did this, and they were. They ran deliberately because they could face no more of the work they have been doing in the last four days.’ Kramer, now nicknamed alliteratively in lurid press fashion ‘the Beast of Belsen’, was ‘caged like a wild animal’ in the camp to save him from being lynched. He was beaten like the other SS men, ‘his pasty face’ showing the lumps of the attacks by prisoners. Few felt any sympathy. With the state of the camp evident to everyone, who would intervene or condemn?

Alan Moorehead, another journalist, was also shown round the camp during those first days.16 After walking amidst the crowds of prisoners (‘there were many forms lying on the earth partly covered in rags, but it was not possible to say whether they were alive or dead or simply in the process of dying’) his army guide asked him whether he wanted to see the SS men and women.

A British sergeant threw open the cell door and some twenty women wearing dirty grey skirts and tunics were sitting and lying on the floor.

‘Get up,’ the sergeant roared in English.

They got up and stood to attention in a semi-circle round the room, and we looked at them. Thin ones, fat ones, scraggy ones and muscular ones; all of them ugly, and one or two of them distinctly cretinous.

The last adjective, or similar, seemed to be one that would become ubiquitous over the coming years. In interrogations and courtroom cross-examination, many SS accused would be labelled as subnormal, moronic, cretinous. At times it was an easy way of explaining their brutalities. Their lack of intelligence supposedly made their actions understandable.

Moorehead was then taken to see the male SS prisoners.

As we approached the cells of the SS guards the sergeant’s language became ferocious.

‘We have had an interrogation this morning,’ the captain said. ‘I’m afraid they’re not a pretty sight.’

‘Who does the interrogation?’

‘A Frenchman. I believe he was sent up here specially from the French underground to do the job.’

The sergeant unbolted the first door, and flung it back with a crack like thunder. He strode into the cell, jabbing a metal spike in front of him.

‘Get up,’ he shouted. ‘Get up. Get up, you dirty bastards.’ There were half a dozen men lying or half lying on the floor. One or two were able to pull themselves erect at once. The man nearest me, his shirt and face spattered with blood, made two attempts before he got on to his knees and then gradually on to his feet. He stood with his arms half stretched out in front of him, trembling violently.

‘Get up,’ shouted the sergeant. They were all on their feet now, but supporting themselves against the wall.

‘Get away from that wall.’

They pushed themselves out into space and stood there swaying. Unlike the women they looked not at us, but vacantly in front, staring at nothing.

Same thing in the next cell and the next where the men who were bleeding and were dirty were moaning something in German.

‘You had better see the doctor,’ the Captain said. ‘He’s a nice specimen. He invented some of the tortures here. He had one trick of injecting creosote and petrol into the prisoner’s veins.’

The Nazi doctor was Fritz Klein. He’d been at Auschwitz, Neuengamme and then Bergen-Belsen for the last few months before the end of the war. The technique of injecting petrol or phenol into the veins of prisoners hadn’t been his invention. I found various references to the technique being used in other camps. The science of killing and torture is frequently one to share, distribute, even inculcate within a corrupted system. Not that this would have mattered much to his British guards. Moorehead was told Klein had just finished being ‘interrogated’.

‘Come on. Get up,’ the sergeant shouted. The man was lying in his blood on the floor, a massive figure with a heavy head and bedraggled beard. He placed his two arms on to the seat of a wooden chair, gave himself a heave and got half upright. One more heave and he was on his feet. He flung wide his arms towards us.

‘Why don’t you kill me?’ he whispered. ‘Why don’t you kill me? I can’t stand any more.’

The same phrases dribbled out of his lips over and over again.

‘He’s been saying that all morning, the dirty bastard,’ the sergeant said. We went into the sunshine. A number of other British soldiers were standing about, all with the same hard, rigid expressions on their faces, just ordinary English soldiers, but changed by this expression of genuine and permanent anger.

Not long after I read Alan Moorehead’s article and while I was looking specifically into the British investigation at Bergen-Belsen, a friend of mine lent me a book. It was a ‘bestseller’ called Hanns and Rudolf about the parallel lives of a British Army war crimes investigator and a concentration camp commandant.17

As soon as I started reading, obliged now by the loan, I was astonished at the coincidence. It’d been written by a journalist, Thomas Harding, whose great-uncle was Hanns Alexander, a member of the investigation team sent to Bergen-Belsen in late May 1945. I recognised the name from the War Crimes Investigation personnel I’d seen listed in various War Office files. Like many in the unit, he was a German national who’d escaped to Britain before the beginning of the war, had served in the British Army and then found himself indispensable when the need for reliable interpreters arose at the conflict’s end. With a Captain Alfred Fox (another member of the investigation team), he’d been sent to interview Dr Klein in a military hospital on 18 May 1945, about a month after Bergen-Belsen had been liberated and a couple of weeks after Moorehead had seen Klein lying in his own blood in the cells.

Harding told the story of Alexander’s encounter with Klein as if he were there:

Klein did not look well. Since his arrest he had been working without pause to clear the camp, carrying corpses into the mass graves. Hanns and Captain Fox took a seat next to his bed and the interrogation began.18

I knew Klein had been drafted in to help with shifting the piles of corpses, part of the liberating soldiers’ rough retribution. Numerous photographs had been taken of him standing in the middle of a mass of dead prisoners, picking up the naked and emaciated, partially decomposed bodies and loading them onto trucks, or taking the arms or legs of a cadaver with another SS man to carry to a pit. One picture appeared on the front page of the Daily Mirror. It made a visceral connection between perpetrator and the multitude of dead victims: Klein surrounded by, up to his ankles in, breathing in the smell of, rotting corpses. For all the rhetoric about legal justice that the politicians and lawyers were emitting in London and Washington, the soldiers confronted by the reality of the camps couldn’t contain themselves. It was an immediate reckoning.

The treatment of Klein, justified or not (and who then or now would have protested or said it wasn’t warranted or shouldn’t have been done?), would have been enough to unhinge most people. The photographs were dated between 18 and 25 April and Klein appeared, in the first of the series, reasonably close-shaven. Only as the days went by did he grow stubble and then a beard. And that was when Moorehead must have seen him, whilst Klein was undertaking his labours amidst the dead of Belsen.

Maybe Lt Alexander’s interpretation of Klein’s condition, as told by Harding, was the result of the corpse-carrying. But given Moorhead’s account, the forced labour amongst the dead may not have been the only reason he’d been hospitalised. If Moorehead was right and the man was begging for mercy, he must have been in a bad way. Even with the lapse of a couple of weeks, the effects were unlikely to have worn off. Then again, the records suggested Klein had contracted typhus, a hazard of being immersed in graves of those who’d already died of the disease. So perhaps his condition when interviewed was the product of a confluence of factors.

Whatever the cause, nothing was made of this summary treatment. Though the ‘laws and customs of war’, upon which the British relied in order to condemn the Nazi accused, required prisoners of war to be ‘humanely treated’ and officers to be spared any labour, no one seemed to worry about the harm done to Klein or the gruesome work he was required to perform, or any ill-treatment by his guards. He wasn’t the only one to be dealt with in this way. By 28 June reports confirmed the deaths of twenty SS guards under arrest in Bergen-Belsen.19 They had all purportedly died of typhus. It was commonly believed that they’d contracted the disease from being forced to bury the bodies of the prisoners. Dr Klein, the man pictured astride that carpet of cadavers, also suffered. But he survived to face trial.

As public demands increased for punishment of those responsible for the conditions at the camps, rather amateurish investigations into what had happened and who was responsible began at Bergen-Belsen. The scenes witnessed were enough to convince that something criminal had happened. But members of the liberating forces gathered evidence with little guidance or skill. Conversations were written down, rough notes taken, but records were sketchy and imprecise and of variable quality. Many surviving inmates, potential witnesses, were allowed to leave the camp and go home. Few left details of their destinations, anxious as they were to escape that still-hellish place.

In London, the War Office assimilated the reports arriving from across newly occupied Germany and decided that the Judge Advocate General (or JAG, head of the army’s legal corps) would be in overall charge of pursuing war criminals. Plans were drawn up for a practical response. ‘Owing to the numbers of war criminals now being uncovered,’ the War Establishment Committee (WEC), responsible for allocating resources for any army operation, wrote towards the end of April, ‘it is necessary to form as rapidly as possible War Crimes Investigation Teams for the purpose of eliciting and recording evidence required by JAG branch in preparation of the cases for trial of such criminals.’20

By 28 April, it was decided that a war crimes investigative team should comprise a lieutenant colonel (legally trained) in command, a major, four captains or lieutenants, a couple of clerks, and three drivers/batmen. They would need a four-seater saloon car and a 15cwt 4x4 truck. The officers and any photographer were to carry pistols and the other ranks Sten guns. Those holding the rank of lieutenant colonel would act as special investigators, as detectives in other words, and the majors would operate ‘as a cross examiner on behalf of the presumptive accused’.21 Even confronted by the terrible sights of the camps, fairness was to characterise the process. No one was to be officially condemned without careful examination of the facts.

Three days later, an order to the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR) HQ was sent commanding the creation of two of these investigative teams. Everything was supposed to be in place by 15 May.22 The bureaucrats decided on the kind of equipment each team would need. The WEC set out a long appendix to the order. It listed five pages of items from braces and water bottles to chisels and screwdrivers to axes and shovels to brushes and lamps to goggles and gloves to cars and trucks to chairs and tables to set squares and T-squares to jugs, paddles, paper (blotting and printing), photographic film, tape, tents for a darkroom, tripods, kettles, pails, stoves, aprons, caps, masks and trousers: everything that could be imagined would be needed to dig up remains, photograph the scenes of crimes, carry out a criminal investigation in the field.

This was the level of planning. Some of the equipment arrived, but the personnel needed to use it didn’t. The gap between administrative design and action on the ground was immense, as those already at Bergen-Belsen realised. Conditions were dreadful. Over forty thousand prisoners were still being kept in the camp for fear the typhus might spread beyond the perimeter. Troops who’d been there since 12 April were struggling to treat the survivors, who were dying at the rate of five hundred a day. They had to dispose of the mounds of corpses too, a task that still wasn’t finished when the main investigating team arrived nearly a month later. If a proper investigation was to be conducted, if the accused were to be interrogated, witnesses of their criminality identified, and evidence mustered, it would take a massive effort. But no one in government seemed intent on taking the task seriously.

This may have had something to do with the official position held by the British on war criminals generally. The government was never that keen on the American plan to try both the major and minor war criminals in some splendid scheme of prosecution. Though they were happy to pursue and try individual Germans for specific crimes committed against British soldiers (crimes such as the killing of the fifty escapees from Stalag Luft III or the massacres remembered from the days immediately before Dunkirk in 1940, when British troops who’d surrendered to SS units were machine-gunned mercilessly at Wormhoudt and Le Paradis),23 the preference was for instant measures. It was Winston Churchill who allegedly first suggested mass executions once the war was won. As early as July 1944 he wrote to the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, in response to learning about the deportation and annihilation of the Jews from Hungary, making no distinction between major and minor culprits:

It is quite clear that all concerned in this crime who may fall in to our hands, including the people who only obeyed orders by carrying out the butcheries, should be put to death after their association with the murders has been proved … Declarations should be made in public, so that everyone connected with it will be hunted down and put to death.24

Nothing had changed with the end of the war. Bergen-Belsen merely confirmed the scale and spread of ‘horrible’ crimes. Nonetheless, with Hitler and Himmler and all the others still at large, political minds were focused on the broader issue of how to deal with the leaders of the Nazi regime.

As the Bergen-Belsen investigators were clumsily uncovering the local stories of atrocity, operating with few resources and, left to get on with their work as best they could, struggling to cope with the enormity of their task, Sir Alexander Cadogan (Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, a civil servant rather than politician, and one who had consistently expressed opposition to an overarching trial) handed an aide-memoire to Samuel Rosenman, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s assistant.25 The note of 23 April 1945 from His Majesty’s Government expressed the absolute certainty that Hitler and ‘a number of arch-criminals’ (they must have been avid readers of Sherlock Holmes) should, when or if they were captured by the Allies, ‘suffer the penalty of death for their conduct leading up to the war and for the wickedness which they have either themselves perpetrated or have authorised in the conduct of the war’. The reasoning for this definitive position was that otherwise it would be ‘impossible to punish war criminals of a lower grade by a capital sentence pronounced by a Military Court unless the ring-leaders are dealt with with equal severity’.

The British government’s favoured strategy was therefore clear: ‘execution without trial is the preferable course.’ Despite all the American arguments that a public and fair hearing should be held, the British wanted summary justice. The aide-memoire warned, at least as far as Hitler and his closest associates were concerned, that a trial, with its demands for proof, would be ‘exceedingly long and elaborate’. Then there were those onerous rights that would have to be accorded to the defendants. ‘There is nothing upon which British opinion is more sensitive in the realm of criminal procedure’, the note went on, ‘than the suspicion that an accused person – whatever the depths of his crime – has been denied his full defence.’ His Majesty’s Government would fight shy of an attempt to interfere with the normal arrangements of a criminal trial, even though fulfilling them might provide the Nazis with an opportunity to grandstand and subvert the whole process. Best then to avoid one altogether.

The sensibilities of the British weren’t taken that seriously. They became less relevant when Hitler’s suicide was announced on 1 May 1945. The Führer myth (as well as reality), inside Germany as well as out, was so strong that his absence from any trial would inevitably lessen the impact of the propaganda value that might be gained by Nazi leaders dragging out proceedings or complaining about procedural technicalities. Besides, the determination of the Americans to obtain justice through a recognisable criminal process had already been decided. President Roosevelt may have died on 12 April 1945, but newly sworn-in President Harry Truman wasn’t about to change the American position. Plans were well advanced in Washington. Crucially, the Soviets agreed that some form of trial should take place. The British were isolated. Realising they were swimming against a tide of international and perhaps public opinion, the British government withdrew its long-held objection to a grand show trial and embraced the idea instead, albeit reluctantly.

On 2 May, President Truman formally engaged Robert Jackson as the Chief of Counsel for the proposed international tribunal. He had won the race to fashion the formal retribution process. He was a familiar figure in US legal circles, having served as Attorney General under President Roosevelt and then as Supreme Court Justice. A man of the establishment, as one would expect. Jackson’s appointment represented a desire for a principled approach.26

By this time the Americans were distributing a draft protocol outlining how the proposed trial of Nazi leaders should proceed.27 In San Francisco at the end of April 1945, whilst the Allies gathered at the United Nations Conference on International Organisation (the inauguration of the UN), the draft was handed to Anthony Eden, British Foreign Secretary, and his counterparts, Vyacheslav Molotov of the Soviet Union and Georges Bidault of France. This was the first attempt to put the idea of judicial retribution into some legalistic form. Only the basic principles were accepted by the four powers at this point (the detail would remain under negotiation for some months), though this was significant enough. By finally affirming that a military-style trial (and a ‘fair trial’ at that, as the draft declared) of ‘Major War Criminals’ would take place (rather than a scheme of summary execution), with evidence and charges prepared by a committee of representatives from each of the four Allied powers acting in cooperation, and by confirming that individual ‘officers and men’ directly responsible for atrocities and crimes would either be returned to the countries where those crimes were committed or tried by the Allies in some other procedure, the method of retribution was prescribed.

After that, it was all about the detail. What crimes were to be prosecuted? What were to be the charges? Who were to be the ‘Major War Criminals’ brought to trial; who would be tried in separate local courts? Much of the legal logistics were made a little easier by the adoption of the military tribunal model. Some impossible fusion of legal systems and procedures in order to find a hybrid to satisfy every nation affected wasn’t needed. Instead, agreement that a court martial, where there would be a prosecution, a defence and a bench of judges to decide the outcome, was an approach each of the powers could understand and embrace.

Whilst these high political manoeuvres were going on in the Allied capitals, matters were improving slightly in Bergen-Belsen. Perhaps recognising the demands of criminal trial, perhaps finally convinced of the importance of gathering proper evidence, Majors Smallwood and Bell, both from the Judge Advocate General’s Office, and Captain Fox of the Special Investigation Branch of the Military Police were sent to the camp. Even then it was a pitifully under-resourced response. German interpreters only arrived more than two weeks later, on 14 May, and these were, as would be noted in formal reports, ‘of no value in dealing with a considerable number of possible witnesses who only spoke Czech, Polish, Russian etc’.28 The officers were also without NCOs to act as ‘searchers’, to identify suitable witnesses and suspects. Three arrived with the interpreters, but it was late and hardly adequate given that there were ‘some 55,000 potential witnesses sick or healthy, distributed over an area of several square miles’.

I imagined those thrown into the hellish conditions did what they could. Major Smallwood gave evidence at the Belsen trial (as it would later become known) and was explicit about how he’d coped.29

When we got there, there was no fixed plan.

There had been some investigations already made by members of the Military Government, but they had not taken any very definite statements. Statements had been taken, but no sworn affidavits or anything like that. So the first thing was to get interpreters. None of us spoke any Czech or Polish, and very little German and perhaps a little French. With the aid of the Military Government we got hold of some interpreters and two girls who were extremely good. They were both ex-internees, Czech Jewesses aged about 25 or 26 respectively. One had been interned for four years and the other for five years in different camps which included Auschwitz and Belsen. They had only just come to Belsen ten days before the liberation and they escaped the full horrors and were therefore in pretty good health. With their aid we started to take statements. Of course, there were thousands of people there and it was difficult to know where to begin. To start with we got them to bring in their friends who were in a fit state to give evidence, and gradually the circle grew. With the aid of the Military Government we got various members of different nationalities to send people along if they could give statements that might be helpful. The procedure at first was that the witness was brought in and we explained to the interpreters, who understood the position very quickly, that what we wanted was evidence of definite acts committed by definite people on, as far as possible, definite dates. We did not want a whole series of people coming along to say that SS guards were brutal and cruel, because one knew that already. We gave these instructions to the interpreters and we got a whole lot of statements from various witnesses. The procedure, speaking for myself, was that I took rough notes as we went along and the witness went away and I put those notes into ordinary affidavit form. The witness then came back and the affidavit was read out to her and translated in my presence by the interpreter. Sometimes small alterations were made then the witness was sworn and signed it.

It wasn’t very sophisticated. Some statements taken by Smallwood were of dubious value. On 8 May he interviewed Hela Frank. All her statement said was: ‘I am 24 years of age. I am of Polish nationality and was first arrested in May 1943. I have been in concentration camps ever since and came to Belsen on 1 November 1944. I knew in Belsen an SS woman called Frau Amper. She worked in the kitchen and often beat people both men and women with a whip who came there. She once beat me with her hands but not very badly.’30

That was it. Slightly more fulsome and useful statements would be taken (none were as detailed as the prosecution officers could have thought ideal), but this was hardly a definitive proof to convince any court to convict this SS woman or anyone else. Not if the standards of normal British justice were to apply. Other statements were better, but looking at the general quality, they were too short, too imprecise to be valuable. They gave no sense of the multitude and prevalence of abuse suffered. But then, how could they? Perhaps only a poet would have been able to do justice to these stories.

In the circumstances, it was all Smallwood and his fellow officers could reasonably manage, or so they claimed. A British War Crimes headquarters had been hastily established at Bad Oeynhausen, a small town west of Hannover, though it was an office dogged by frustration and lack of support from government back in London from the start. Only on 20 May 1945, more than a month after Bergen-Belsen had been liberated, was some kind of team, as originally envisaged by the War Office, finally assembled in the camp. What was now known as No. 1 War Crimes Investigation Team took shape and began work. A Lieutenant Colonel Leo Genn was appointed to command the operation.

At first, I didn’t dwell much on the identity of those sent to investigate the atrocities at Belsen. They were just faceless names on a page. But then I came across the unpublished memoirs of Fred Warner almost hidden amongst the papers of another investigator, Anton Walter Freud, in the Imperial War Museum. Warner, it seemed, was one of the numerous German nationals who’d escaped Germany in 1939 and sought refuge in Britain. He was considered reliable enough to serve with the Royal Pioneer Corps in Britain before being recruited to the Special Operations Executive and parachuted into Italy behind enemy lines in early 1945. A few months later, he was invited by Major Gerald Draper at JAG to join the War Crimes Team as an interpreter and investigator.31

Warner, born Manfred Werner in Hamburg, had been posted to Bergen-Belsen as soon as he was recruited by Major Draper. The officer to whom he’d reported at the camp was ‘quite a celebrity’, he wrote. He mentioned the name Genn, which triggered a vague memory of one of those English actors who’d appeared regularly in numerous films during the 1950s and ’60s. He was in The Longest Day, the iconic 1960s film about D-Day, and The Wooden Horse, another war movie about a notorious escape from a German POW camp. When I looked up his photograph, I remembered the polished English persona, exuding calmness whilst everyone else about him panicked – the quintessential Englishman of Empire. How, I wondered, had he come to command this vital first investigation?

Some details weren’t difficult to find. Leo Genn was a lawyer. He’d studied law at Cambridge in the 1920s and even practised as a barrister in London for a short time. But acting was his true passion.

After a couple of years at the Bar from 1928 to 1930, he met the wonderfully named stage actor and producer Leon Lion. Lion encouraged Genn’s theatre acting whilst having him help out as legal counsel. Genn’s acting career flourished and by the mid-1930s he’d already appeared in films and had been taken on as a member of the Old Vic Company. His smooth voice and equally smooth features made him ideal for the movies and the stage. He appeared in a succession of plays both in London and New York as well as the odd film now and then. The war changed that. By 1940 he’d signed up with the Royal Artillery. His thespian skills weren’t forgotten, though, and he was drafted in to narrate official war films. (You can listen to recordings of his voice-overs in the Imperial War Museum’s archive.) In 1944 he was given leave to act in Laurence Olivier’s Henry V. It must have been strange for him to leave his unit, fighting across France, to go home and pretend to be fighting the fifteenth-century French.

At first I had no idea how he’d been chosen as commanding officer of the Belsen investigation. He didn’t seem to have the obvious profile for a war crimes investigator. But then I came across a comment made by Major Smallwood at the Belsen trial that was to take place later in 1945 that suggested Genn had served in the SHAEF Court of Inquiry, which I now knew had examined various massacres of Allied troops taken prisoner during the Battle of Normandy and in the campaign across northern France and into the Low Countries.

Whether this was true I couldn’t say at first, though it would have explained his appointment. Few others would have had similar experience; the Court of Inquiry had only investigated a few dozen cases during its short life. Then again, it occurred to me ungenerously that perhaps his glamour and charm and growing celebrity, coupled with his rank of lieutenant colonel and the Croix de Guerre on his chest, might have made him an irresistible choice for the War Office. With a whole department of long-serving lawyers in the Judge Advocate General’s Office back in Whitehall, why else would they have selected a man who clearly had only a cursory interest in the law, had little if any investigative experience in civilian life, and had never practised criminal law to any great degree? I thought legal counsel to theatreland during the 1930s hardly qualified him to take on the largest and most complex criminal investigation Britain had ever undertaken, perhaps would ever undertake. It reinforced the impression of amateurism, of a British military and governmental arrogance that an officer with limited experience in a specialist field would be able to cope.

I was wrong. Up to a point. Searching further amongst the Foreign Office records, I found that Genn had indeed been appointed as a member of the Court of Inquiry at the beginning of 1945 to serve alongside the Canadian, Col Bruce Macdonald, and the American, Col John Voorhees.32 Travelling around France and the Netherlands they scrutinised the suspected murder of many Allied servicemen. At Tilburg they investigated the shooting by the Gestapo in July 1944 of three Allied airmen, an Australian, a Canadian and a Briton.33 The men had been hiding at a Dutch underground address in the town when the house had been raided by the Germans. Witnesses were found who could testify to having seen the Gestapo members executing the airmen in the back yard. The Inquiry gathered them together and over the course of a day asked them questions about what they’d seen and then produced a reasoned set of findings. It was detailed work. Genn and his colleagues had surveyed the house, producing plans of the scene and marking the location of the shootings; they’d found photographs taken by the local Dutch police of two of the dead men (pictures of the tops of their heads wrapped in cloth like some 1940s charladies, their shirts soaked in blood, their mouths open); had taken their own photographs of the back yard from nearby windows where witnesses had watched the executions; and had identified the perpetrators. The report was composed and exacting in its attention to the ‘facts’. But what could it offer? Simply, a recommendation that should the named Gestapo members fall into Allied hands they should be brought to trial and charged with murder.

Genn also visited the village of Le Paradis, where the infamous massacre had been perpetrated upon members of the Royal Norfolk Regiment and other units during the retreat to Dunkirk in May 1940. Ninety-seven men had been captured, gathered together in a farmyard and machine-gunned by an SS unit. But Genn and his fellow investigators couldn’t identify the German troops involved with any certainty. They could only plead for the Allies to search for more information.34

There were several cases like this. Each produced a carefully typed report deposited with SHAEF headquarters. No doubt the details were passed on to London, but I couldn’t quite understand why such work had been undertaken at a time when the war had yet to be won, when there was so much death and devastation to contend with. What had it achieved? A reaffirmation of decency formulated by legal process? Maybe that was enough.

Nonetheless, Genn’s experience made him the natural choice for taking on the case of Bergen-Belsen. Few others had had to dig up remains of their comrades to determine a victim’s cause of brutal death, had cross-examined witnesses, had sought the necessary information to identify German perpetrators, had acquired the skills to pursue an investigation in the best traditions of British justice.

The appointment of Genn was, I thought, a logical one after all. He was a lawyer, he was in the field, he was ready to move to Germany. But then I found out later, after finally tracking down his private papers, that ambivalence, perhaps even resentment, had accompanied Genn’s acceptance of his new mission.35 In his seemingly aborted memoirs (deposited with the IWM and amounting to only half a dozen pages, tailing off before he’d finished telling the story of his time at Belsen, perhaps having lost faith in his ability to write something worthy, the style laboured, doing little justice to the terrors he’d been recalling) he complained, first, about the way in which the SHAEF Court of Inquiry had been precipitously wound up, a decision he reckoned must have been made by ‘a member of the Combined Staffs in Washington, under the influence, one can only imagine, of a good lunch on a Spring day’. It was a ‘destructive order’, he said, disbanding a functioning unit in the middle of vital war crimes investigation work, as he saw it. And as for his new commission, Genn wrote, it seemed to me acidly, ‘the dictates of publicity were paramount and concentration camps must have priority over offences against our own serving personnel. This might perhaps be the place’, he continued, ‘to note that in the hearts of all of us who had any operational experience whatever, this particular fact remained one for exasperation and lasting regret.’

Whatever his reservations, when Lt Col Genn took up his post at Bergen-Belsen he brought with him Major Savile Champion, a solicitor in the Royal Artillery, Lieutenant Robichaud (a Canadian army translator who’d served with Genn on the SHAEF Court of Inquiry), Lieutenant Alexander (the Hanns in Hanns and Rudolf, although he then called himself ‘Howard’ to assimilate into the British forces more easily), two other interpreters and about ten other ranks. It represented a significantly better investigative presence than before.

Surrounded by the Stygian scenes of the dead and barely living, these men had to undertake an unprecedented task, with experiences that were impossible to imagine for those who weren’t there, breathing in the stench, witnessing the corpse-strewn grounds. Simply burying the dead was a daily terror for the British troops. If General Patton had thrown up in Ohrdruf and the stomachs of the army medics had turned, what chance did these lawyers have?

Even without the psychological impact of the conditions they had to bear, Genn and Champion recognised that simply bringing order to the camp would take a ‘herculean’ effort.36 They grumbled that despite the expanded investigative team, they suffered from a ‘desperate lack of personnel’. They believed there were only enough of them to conduct an ‘ordinary investigation of a particular’ war crime, not of a whole history and system of atrocity. The more they delved, the more the scale and spread of crimes committed were revealed. Genn and Champion later reported, ‘Twenty such [investigation] units could well have been employed without being entirely adequate to cover the field.’

It didn’t help that men assigned to their investigative team were being poached soon after arriving. Such was the apparent dearth of available lawyers of quality throughout the British zone of occupied Germany that Major Bell had been sent to the 1st Canadian Army on secondment and Major Smallwood was required to sit as Judge Advocate in other military cases. After some struggle with Legal Division, Genn managed to secure Smallwood part-time, hardly satisfactory given the huge demands of the investigation.

Carrying out a full inquiry in these circumstances was difficult enough, but they also felt they were operating in a legal void. They weren’t clear about the limits of their jurisdiction or the charges that could be levelled against the SS men and women in custody: was it ‘neglect’, ‘mass murder’, ‘gross cruelty’, some other offence? The crimes they were hearing about were far outside their experience, anyone’s experience, and the overwhelming suffering they could see in the prisoners who’d survived and the stories that were accumulating through their interviews made them wonder. A ‘single instance of murder or brutality appears in the nature of a drop in the ocean in the light of the many thousands of deaths caused over a period of time by the joint deeds of all concerned’, they wrote, as though they were seeing the evidence transcend the words and notions they had of ‘crimes’. They needed new terms, a completely fresh language to express the enormity of all that they were hearing.

No one had briefed them on the discussions in the UN War Crimes Commission committees, which were toying with the idea of ‘crimes against humanity’ as a new internationally recognised offence. No one made reference to a category of crime being promoted by an unknown visionary called Raphael Lemkin, a Polish refugee who since the early 1930s had seen the rise of Hitler and the atrocities committed against the Jews under the Nazis. Lemkin coined the term ‘genocide’ to describe the planned killing of a race or people with the intent to annihilate such a group.37 He itemised aspects of destruction from the economic and political to the religious and the moral and the physical too. Even in 1944, he was able to chart how the ‘Jews for the most part are liquidated within the ghettos, or in special trains in which they are transported to a so-called “unknown” destination’.38

Though Lemkin didn’t have the details of these final destinations, Lt Col Genn and his team did. As questioning of witnesses continued, they discovered that a large number of the inmates and SS members had been transferred to Bergen-Belsen from Auschwitz when that camp had been shut down at the end of 1944. The stories they were hearing about the latter camp were of gas chambers, industrial-scale killing, years of slaughter of the Jews and many others in installations built for that purpose. This was the reality of ‘genocide’, even if the word was yet to be commonly adopted. Initially focused on collecting evidence for prosecuting those responsible for the terrible scenes at Bergen-Belsen, they now had another priority: investigating the ‘mass extermination in gas chambers at Auschwitz’.

The extension of their remit after their discovery wasn’t reflected in any increase in resources. Lt Col Genn still had too few officers and men in his team and those he had were inexperienced. Matters were complicated, rather than helped, when investigators from other Allied armies came. The officer in charge of the camp, Brigadier Keith, complained at the end of May that two Czech investigating officers had turned up unannounced and a whole team of French officers had ‘arrived with two broken down cars on temporary loan only’. ‘They must come with proper cars,’ he wrote to SHAEF headquarters. ‘They have no typewriters or stationery either. Will you drum it into them that they must come properly equipped.’39

Meanwhile, Genn tried to ameliorate the pressure by jettisoning the plan thought up back in London that he should act as principal investigator and his second in command, Major Champion, should sit by his side making sure those accused were treated fairly and witness testimony was challenged before being passed to the prosecutors at JAG. Genn’s report towards the end of June 1945 said, ‘It has been found impracticable to use both the CO and 2 i/c on single deponents since it would have cut down the amount of work done in the available time by approximately half.’ But the report affirmed that ‘all officers of the unit taking depositions have, however, borne strongly in mind the fact that the interests of the accused should be watched. Witnesses have been questioned with this object in view and the testimony of those considered unreliable rejected.’40

The splitting of Genn and Champion to conduct interviews was a feeble measure. Tens of thousands of potential eyewitnesses amongst those left in the camp would have had something to say. All of them could testify to the conditions and the cruelties. But they couldn’t all be examined and prepared to give evidence. Many were sick with typhus. Many were dying. And those who were well enough to be released had been let go before the investigating team had arrived. The investigators needed good witnesses, reliable figures, people who could say something specific against individual SS members. Genn estimated around 400–500 SS men and women had served at Bergen-Belsen, of whom they had 50 or so in custody. That was a lot of potential defendants who had to be tracked down and against whom some evidence would be needed.

Some of the investigative desperation was apparent from the way in which witnesses were sought. A public address announcement, broadcast about the camp by loudhailer, pleaded: ‘Any person who can give evidence of brutal conduct or murder by any SS men or women at Belsen and has not already given evidence should call at War Crimes Investigation Office Camp 3 Block GB2 First Floor, Room 52 between 10 and 12 in the morning or 2 and 4 in the afternoon. Evidence as to any of the SS men or women having taken part in selection parades for gas chambers at Auschwitz or elsewhere is also required.’41

Whatever was happening with investigations underway at Bergen-Belsen and other camps was incidental to the pursuit of those most senior Nazi figures wanted for the planned Major War Criminals trial. With Hitler’s death confirmed by the Russians on 1 May, as was the suicide of Josef Goebbels, the infamous Propaganda Minister and another of those ‘gangsters’ identified throughout the war as central to the Nazi regime, the Allies began to round up anyone they could find. Franz von Papen, a key politician in Hitler’s rise to power, but latterly a peripheral figure as German Ambassador to Turkey during most of the war, was taken early by the Americans in Stocklausen, Austria. Alfred Rosenberg, the Nazis’ so called ‘philosopher’ who’d been prominent in defining their racial theory, was arrested in Flensburg near the Danish border on 18 April.

Then on 8 May the biggest catch so far was announced. Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering, Commander in Chief of the German Air Force, had been picked up by US General Patch and his 7th Army as they hunted for Nazis through the Austrian Alps. Goering was reported as having surrendered along with his wife, child and members of his staff near Salzburg. He was allowed an extraordinary degree of respect, in spite of the many stories naming him as one of those who would be tried as a war criminal. The Americans presented him rather naively at a press conference after his capture.

Goering expounded on any subject the reporters asked.

Why had he ordered the bombing of Canterbury?

‘In revenge for the British bombing of a German university town, the name of which I cannot remember.’

Was Hitler dead?

He believed so.

And what about the concentration camps being unveiled across Europe?

The Times reported Goering as saying they ‘were solely Hitler’s concern and were run under his direct orders. He never discussed them with anybody but those actually in command of them.’42

Goering’s defence was already in preparation. He denounced the idea that he was a wanted war criminal. He railed against the preposterousness of such a claim. He said he acted only in the best interests of Germany as a high-ranking minister of state of a sovereign country. There could be no question of him committing a ‘crime’ in this context, he said. That would undermine the whole concept of state sovereignty. He would take responsibility for his actions, but he was not a war criminal. The distinction was vital for his sense of honour.

Over the next few weeks other notorious Nazis were arrested. Many had gathered in Flensburg on the Danish–German border. Officials had made for the town with the imminent fall of Berlin and in the hope of maintaining some order away from the advancing Russians. The British found them there, but allowed them to pretend that they were still running the country whilst it was decided what to do with them. Only after a few days were the leaders placed under arrest. On 23 May, Admiral Doenitz, nominal President of Germany in the wake of Hitler’s death; senior military commanders General Jodl and Field Marshal Keitel; Minister of Armaments Albert Speer; and numerous other lesser figures were finally taken into custody. It was the end of a ridiculous interval. Despite their outlaw status and despite the collapse of a functioning chain of command, senior Nazi figures had been left to act as though they still held some legitimate position as the government of Germany.