Cemeteries are curious places for me. Ever since my grandfather showed me lovingly around the churchyard at All Saints’ Church in Newland in the Forest of Dean, a spectacular and verdant plot that far exceeds the needs of the tiny village which it serves, I’ve never feared graveyards, memorial grounds, any place where the dead are gathered and remembered in stone and painting and garden feature. Often, they reveal more about the living who tend them, live close by them, than those who are buried there.

Lüneburg’s Zentralfriedhof is a wide expanse of land bounded by Soltauer Straße entering the town from the south, pleasant modern housing along Oedemer Weg to the north and Heidhamp to the west. The map printed on a large sign at its main entrance shows the cemetery as a triangular patch of woodland cut through by a maze of pathways that link little clustered memorials within the trees.

Apart from the grandiose gravestones of the rich townspeople, the cemetery has several groves where German war dead have been buried or remembered simply by some obelisk or plinth or thick stone block. The First World War memorials are the most visible, the most unashamed. Though World War II casualties have been inscribed onto the rolls of honour here and there, tacked onto the remembrance stones, a timidity of purpose accompanies the additions. I wondered if the authorities debated whether it was right to pay respect to those who’d died in the service of the Nazi state. There must have been some reticence, some worry that one or more had taken part in the pervasive crimes then coming to light.

The war graves looked shabby and untended in the April sunshine of a Saturday afternoon. Most of the individual stubby crosses, which recorded the name of the fallen soldier and no more, were reminiscent of the Iron Cross medal of the German military rather than some Christian symbol. They were laid out in beds of creepers that had spread around and over the stone faces. Many were completely obscured.

As I walked along one avenue I found myself contrasting the way in which respect for the dead was displayed here with that at home and in the beautifully tended Commonwealth War Graves plots around Europe and the world. In Britain, every hamlet, village and town has its war memorial, usually well cared for, but here they didn’t seem to bother too greatly. Did the shrouds of ivy and plants signify shame?

Perhaps. There was much to be ashamed about. And I thought that the trials held by the British in those months after the end of the war were intended to reinforce, perhaps induce, that sensitivity.

Heading out of the cemetery and towards the old centre of Lüneburg I looked for some plaque or notice commemorating the town’s role as home to the first significant war crimes trial by the British in 1945. I couldn’t even find the building where the trials had been held. At the time I visited, I hadn’t known the address, stupidly hoping there would be directions and signposts somewhere in the town. I found nothing: no marker, no waymark, no memorial. It was becoming a common experience.

When I looked at the website of the local tourist bureau all I could see was praise for Lüneburg’s fortune in escaping the war unscathed: it’s now a ‘lovely place to shop’, the old cobbled streets lined by gabled houses and boutique cafés and fashion stores. Why would you want to spoil all this with refracted sights of an unpleasant past? Perhaps allowing the building where so much viciousness was spoken of to be assimilated into the urban landscape, much like the graves in the Zentralfriedhof, was a reasonable policy: let the marks of the past disappear, let them be overgrown, it’s better that way.

I settled into one of Lüneburg’s pleasant coffee bars, a poor substitute for the old courtroom I’d hoped to see, and thought about how my search for some traces of a time long buried beneath economic prosperity and political alliance was proving difficult. I wondered about the vagaries of official history too. What’s remembered is so much a matter of chance, or so it first appears. Bergen-Belsen was the British trial of the century, held in this unspoilt town. It was the British trial of the Holocaust, the first occasion when the Nazi extermination of the Jews through industrial means could have been, should have been, the subject of specific and prolonged exposure. And yet the process never quite assumed that character then, nor has it since. The case is rarely referred to as anything other than the ‘Belsen trial’. It isn’t often known as the Auschwitz–Belsen trial even though the prosecution would make it clear from the beginning that the Polish extermination centre at Birkenau was a central element of the charges against many of the SS men and women accused. Instead, the trial is associated more with the black-and-white films of liberation, the moment when British troops encountered the pit of Bergen-Belsen.

Some of this is understandable. Time didn’t allow for sustained reflection before the case was heard. The pressure to prosecute as quickly as possible, to ensure that the public would see a vigorous and swift retribution following the pictures and newsreels of Bergen-Belsen, meant that all the investigators and lawyers were operating under extraordinary burdens. They were given only a few weeks when the demands of the law required months if not longer. It was a tension (between the political need and the legal) that was never resolved and which paved the way for much criticism.

On my return from Lüneburg I went back to the National Archives at Kew. I read through the Belsen trial files kept by the British authorities. It took some time. There were many boxes full of typewritten transcripts, exhibits, general court correspondence. They recorded every word of those proceedings and as I scrutinised them the trial assumed a voice just as a stage-play script might do. It was an act of theatre and here were the lines and the directions. With some irony I later found a memo in a War Office file devoted to the administrative arrangements for the trial which addressed the question of where the proceedings could be held: the memo by a Major Harris said they’d first considered the huge castle at Celle, but the only room large enough was the Schloss theatre: it was dismissed as a suitable venue with a terse comment, ‘theatrical atmosphere felt to be undesirable’.1

The Old Gymnasium at Lindenstraße 30 was only a few hundred metres from the town cemetery, along Soltauer Straße. An ugly twin-towered brick building (from what I could tell from the photographs taken at the time), it was identified as acceptable for the hearing by the British Army, who’d occupied the town and made it the headquarters of 21st Army Group in April 1945. Inside was a large hall to accommodate the multiple defendants, their many lawyers and a huge audience, though building works were necessary to convert it into something that would look like a court. No one wanted this to be a hidden affair. It had to be public and open and capable of alerting the world to what had been done at Bergen-Belsen.

The Americans had yet to begin their set-piece war crimes trials, so it was the British who were the first to stage proceedings that tackled the worst of the atrocities committed by the Germans. Bergen-Belsen, or rather the truncated ‘Belsen’, was synonymous with the horror of Nazi barbarism. Though Buchenwald and Ohrdruf and the euthanasia centre at Hadamar had been discovered earlier and their terrifying secrets revealed in the press, the British were determined to bring the Bergen-Belsen personnel to trial before people could forget what had happened. The public were fickle, anyway, tired of blood and massacre, tired of war and everything associated with it. If the rhetoric of justice was not to lose its veneer then an immediate demonstration of the evils perpetrated and punishment for those responsible was necessary.

No one objected to the timetable publicly, though the lawyers must have doubted the value of such extraordinary haste. They knew that to present a proper case and mount a suitable defence, mimicking the best traditions of criminal justice, they needed time. As it was, the attorneys who represented the defendants were only appointed a few days before the trial. Within that period they were supposed to prepare their clients and identify and bring to court any witnesses who might aid their defence.

Major Thomas Winwood had the task of defending Josef Kramer, now called as of rote the ‘Beast of Belsen’ even though his tenure as commandant in both Natzweiler and Auschwitz II-Birkenau lasted much longer and, in the case of Auschwitz, involved the deliberate extermination of hundreds of thousands of people. Winwood was also responsible for representing three other accused, including the camp doctor, Fritz Klein. It was a heavy load for one lawyer. Either of those SS officers could have eaten up all the short time available to prepare a case. But Winwood wasn’t intimidated and protested little. He later wrote a short memoir of his experiences at the trial, which betrayed the amateurism inherent in the appointment of defence counsel.2

In the early summer of 1945 [he said] I saw a notice from the Headquarters of the British Army of the Rhine requesting the names of serving officers qualified as barristers or solicitors. I had qualified as a solicitor in 1938 and ignoring the first rule of Army life – ‘never to volunteer’ – I sent in my name. Some two months later I was ordered to report the following day at RAF HQ in Celle.

The next day I was greeted by a Staff Officer who told me, ‘Well, as you are the first to arrive, you had better take the first four on my list.’

Only then was Winwood told he was to defend the Bergen-Belsen camp commandant. He had thirty minutes to read the papers before seeing his clients, seven days before the trial was due to begin.

Twelve defence lawyers, all British officers appointed in similar cavalier fashion, looked after the interests of the forty-two accused. They tried to coordinate their defences but, as Winwood recalled, they ‘had little time to formulate a coherent defence policy beyond agreeing that we would put forward a joint objection to the jurisdiction’.

On 17 September 1945, the case opened and was fêted in the world’s media. It would be the first opportunity to see justice administered against the Nazis whilst everyone waited for the Nuremberg proceedings to begin. Newspaper correspondents had already been briefed on the characters they would see on trial, some of the wickedest individuals imaginable, men and women, and portrayed as sadistic, unfeeling brutes.

The courtroom constructed in Lüneburg’s large gymnasium hall allowed for numerous reporters and observers to squeeze in opposite the bank of defence lawyers and behind them, the massive three-tiered dock where the accused would be seated. A public gallery could hold four hundred people and it was full too. Some brought binoculars to get a better view of the participants.

A series of photographs published in the Illustrated London News showed the prosecution team sitting in a dignified line behind a table covered with files and papers.3 The names ascribed to the men were wrong: Leo Genn was on the left of the picture, sitting next to Captain Stewart. Colonel Backhouse, the lead prosecutor, was on the far right.

The paper had pictures of the defendants too: Josef Kramer leaning forward in the dock, smiling and chatting with his British attorney, Major Winwood. And there was a fetching shot of Irma Grese, accused Number 9, looking icily beautiful.

The show began.

No one could deny the theatricality of the event, despite the precautions. It was a strange combination of military precision, a court martial operated in accordance with army regulations rather than new international legal directives, and the ceremony of criminal law. The Deputy Judge Advocate, Carl Stirling, the lawyer who was to guide the judging panel of army officers throughout the case, to interfere where necessary, to sum up evidence at the end and generally oversee proceedings, was dressed in black robe, white winged collar and wig. Advocates stood when they spoke and faux politeness prevailed.

As the defendants were marched in to take their seats, shuffling along into the three rows of benches within the wooden dock, with numbered cloths hanging around their necks, any idea that this was an occasion of immense and national reckoning was diminished, perhaps erased. It quickly became apparent that the ordinariness of proceedings dictated the style: the defence lawyers steadfastly refused to recognise the world outside the legally confined room and the case opened not with a fanfare of condemnation, but with applications of legal technicality, all raised on behalf of the defence. Major Cranfield, acting for Irma Grese (the SS woman guard who more than anyone would capture the press’s attention), spoke for the defence lawyers en masse and immediately made some practical requests: whilst noting (not complaining about) the limited time he and his colleagues had had to prepare, he said they should be provided with an expert in international law so that they could challenge the whole basis of the charges against their clients; and he wanted the prosecution to bring witnesses to the court whom he and his colleagues had named in a long list. Captain Phillips, who acted for four of the lesser accused, asked for separate trials, claiming it was wrong that one set of defendants were charged with crimes committed at Bergen-Belsen only (including his clients) and another lot were charged with crimes committed at Bergen-Belsen and Auschwitz. Phillips was concerned that evidence brought about the latter camp, evidence that would demonstrate the policy of mass and deliberate extermination of a people, would prejudice the panel’s view of those who’d only served at Bergen-Belsen, a different type of camp where death was more a matter of neglect (or so it would be said) than measured slaughter. There was a great difference, he said, enough to warrant separate hearings to avoid prejudice.

Colonel Tommie Backhouse, the chief prosecutor (a barrister from Blackburn and a member of the Judge Advocate General’s Branch during the war, now officer in charge of the War Crimes section of the British Army of the Rhine), responded by suggesting there was nothing to choose between the two camps. ‘The individual methods of ill-treatment sometimes varied because … every known method of ill-treatment was used at one or other of these camps. Nevertheless, the same people were acting as concentration camp guards in one and went to the other and acted as concentration camp guards there. They ill-treated people, and literally the same people at Auschwitz as the people they ill-treated at Belsen.’

Was this dissembling? ‘Ill-treatment of people’? And the same people? Could that really have been the core of the prosecution’s case, the appropriate language to describe the evidence to be presented? If it was an understatement then it was ill-conceived. Reading through the trial papers, I suspected caution had infected the prosecution lawyers’ work. This was a unique moment after all. No one had undertaken anything like this before. They might have thought that by choosing a restrained terminology of wrongdoing, the defendants would have less chance to raise a reasonable doubt concerning their guilt. For all the pictures of piled corpses, it was still hard to believe or comprehend the prolonged and industrialised and centrally controlled form of killing that had occurred in Auschwitz. By presenting a charge of lowest common denominator (concerted ill-treatment rather than ‘extermination’ or ‘mass killing’ or even ‘murder’) the chances of the guilty going free were much reduced. Hannah Arendt, the renowned German political philosopher, would ask later, ‘What meaning has the concept of murder when we are confronted with the mass production of corpses?’4 So too might the prosecution lawyers have wondered how to capture the totality of crimes committed by the accused over a period of years and in two by now notorious camps.

The prosecution’s case was forged from Lt Col Genn’s initial investigation report and recommendations. Genn sat next to Backhouse as he delivered his opening speech, having returned to assist in the completion of his work, back from Britain where he would shortly resume his successful acting career. Captain Stewart was there too, the team looking like a row of forties film stars, which of course Genn was fast aspiring to become, having already appeared in Laurence Olivier’s Henry V. They’d agreed that the best approach, the safest, was to condemn the individuals by their association, their connivance with an abusive design, criminal by the standards of the laws of war. They’d agreed to fuse the evidence on Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen in one trial. What was the point, after all, of prosecuting Kramer and Klein for their deeds at Bergen-Belsen: to seek and surely obtain their death sentence, and then open another case in relation to the evidence they had about Auschwitz? The Russians as occupiers and the Poles as a sovereign people had geographical jurisdiction over Auschwitz, and under the terms of the Moscow Declaration of 1943, Kramer and the others would then have to be extradited to them to prosecute. The opportunity to see Kramer and the others hang for the horrors of Bergen-Belsen wasn’t to be given up so easily. Besides, as Backhouse had said, so many accused had served in both camps and so many inmates had been held in both as well. It would be absurd to ignore that evidence when the world wanted to know what these men and women had done, what evil system had been invented. But if the intention was to unpick the wickedness not only of the individuals but also the regime that served up Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, then there were some odd omissions in the charge and in Backhouse’s introduction. There was no mention of the plan to exterminate the Jews. There was no mention of the philosophy or ideology that was the foundation of the policy. There was no mention of the years of persecution that ran through the period of Nazi rule, from before that date, from the 1920s when Hitler and his party took shape. There was no mention of when persecution was transformed into the deliberate annihilation of whole peoples. There was no mention of the Gypsies either, the Roma and Sinti who had a camp of their own within Auschwitz. There was no mention of any of this.

Why did the prosecution avoid this hinterland of criminality? What were they afraid of? Or were they largely ignorant of the complexities and magnitude of the extermination the Nazis had carried out? The trial was hastily arranged after all and the evidence accumulated was local: witnesses were those who had been found alive in the camp on liberation and seemed credible men and women. No attempt was made to construct a documentary presentation of Nazi rule. Only a few papers were presented. Unlike the tribunal being prepared in Nuremberg, where documentation was the mainstay of the case, the crimes addressed at the British Belsen trial were contained and very personal. Did it matter whether the individual SS personnel accused were acting as parts of the Auschwitz machine when witnesses could point at them and tell the court that this man, this woman, wielded a whip, crushed an inmate, beat another to death, routinely set vicious dogs on prisoners, stood at the ramps at the railway sidings inside the entrance of the camp and selected thousands in person to be taken to gas chambers for killing?

Perhaps it did. The Belsen trial would be the only British or American trial that directly examined individual deeds at Auschwitz. None of the other extermination camps, Treblinka, Sobibór, Belzec, would figure in the Western Allies’ cases explicitly. Being in the east, these places were the preserve of the Polish and Russian governments. By drawing the two camps of Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen together, through its personnel and victims, the prosecution claimed that a policy of extermination defined a systematic criminal practice and the accused were acting together to see that system fulfilled.

The phrase used was ‘concerted action’: the defendants as a unit operated to commit war crimes. That was the charge. The defence lawyers tried to analyse the words. One even pulled out his Little Oxford Dictionary. Captain Phillips for the defence said that ‘concerted action’ implied ‘a certain amount of common intention or common action between various people to contrive, to premeditate and to plan’. He argued the prosecution couldn’t prove this. Where was the evidence? Colonel Backhouse said it lay in their conduct: all the kitchen SS and Kapos behaved with equal despicability towards the camp’s inmates, all the SS guards and Kapos on trial exacted similar punishments, all the SS and Kapos looking after the medical care of the prisoners inflicted more injuries, conducted experiments, saw to it that people were killed rather than attempt any cure; together this had to suggest concerted action. If they all behaved in the same way then they must all have been following a single design: and that was enough to prove the charge.

However persuasive this argument was, by definition the plan extended far beyond those on trial in Lüneburg. The accused were minor players within an epic story. Proving they and they alone were acting in ‘concert’ would be a falsity just as much as claiming their deeds in Bergen-Belsen should be examined in isolation. With the proceedings yet to begin at Nuremberg, the Belsen trial had nothing to which it could anchor itself. Only the general outrage of years of war as covered in the newspapers and Pathé film clips provided a backdrop. It was a bind which the prosecution lawyers couldn’t escape.

The military panel considered the request by the defence for separate trials. And then denied it. There was to be no derailment of proceedings at the first juncture, whatever cogent legal arguments were raised.

A few hours were lost before the defence lawyers’ initial applications were dismissed, then Colonel Backhouse was finally allowed to introduce the case.

He embarked on a torpid tour through the technicalities of the charges laid against the accused, whom he referred to as ‘members of the staff’ of either Auschwitz or Bergen-Belsen or both. He quoted the royal warrant, articles and paragraphs at a time. He explained that they were not concerned with abuses committed by Germans on Germans, only Germans against Allied nationals. That was all the laws of war were capable of covering. It took him some time before he peppered his speech with invective against the accused and the system they served. He told the court that the thousands of verified deaths in Bergen-Belsen before and after liberation were the result not of criminal neglect but of deliberate and wilful killing. He introduced the camp at Auschwitz as particularly despicable. He described the ‘selections’ where those arriving in cattle trucks would be separated as soon as they were hauled off the trains: to one side, the fit and potentially useful labourers; to the other, the sick, the old, the young, the majority. He numbered those killed in the millions.

But a trial is an intimate event even when performed in public and even when weighed down by legal technicality. The accused have to be identified, given a personality. Despite the numbered cards around their necks, the defendants had to be brought to life: the principle of individual responsibility demanded it. Colonel Backhouse introduced the accused like a cast of characters in a drama, using the numbers on the small white squares that marked the defendents as a guide. The star villains came first.

No. 1 was Josef Kramer, commandant at Auschwitz and commandant at Bergen-Belsen. Backhouse told the court it would hear that Kramer joined the SS as a volunteer, and had been a concentration camp official ever since. It may be, he said, that evidence will be put before you of incidents at other concentration camps if the defence persist in their suggestion that what happened at Bergen-Belsen was accidental and not part of an organised series of events.

Then there was Dr Klein, a Romanian, a volunteer in the Waffen-SS since June 1943, serving in the camps since December of that year. You will hear witness after witness tell how he selected victims for the gas chamber at Auschwitz, Backhouse said. You will hear that he makes no secret of it.

Next, Weingartner, Blockführer of one of the women’s camps at Auschwitz, a thousand women under his orders. He continued the same work when he was transferred to Bergen-Belsen.

Kraft was an SS guard at Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen who oversaw the bread and ration store. Then Hössler, Auschwitz too, Lagerführer, senior SS officer under the commandant, joined the SS because he was out of work, and served in concentration camps throughout the whole of the Nazi era. In charge of the women’s camp under Kramer. After he left Auschwitz he went to another camp called Mittelbau-Dora, and from Dora to Bergen-Belsen, where he became Lagerführer of No. 2 Camp.

Bormann, female, was in charge of the clothing store first and later the working parties at Auschwitz. You will hear how she amused herself by setting dogs on women and taking part in the selections for the gas chambers, Backhouse said. You will hear that when she came to Bergen-Belsen she was in charge of the pigsty.

Elisabeth Volkenrath: at Auschwitz she regularly took part in the selections for the gas chamber; cruel. At Bergen-Belsen Kramer placed her in charge of all SS women. You’ll hear of her many brutalities.

Herta Ehlert, SS guard. She claims to have been a conscript, spending a career in various concentration camps before eventually arriving in Bergen-Belsen after a spell at Auschwitz. She was the second in command of the women, and like so many others will say the conditions were a disgrace, but, of course, everybody other than herself was to blame.

Then there was Irma Grese, commandant of working parties, and, for a time, in charge of the women’s punishment quarter at Auschwitz too. Some will say she was the worst woman in the camp. Not one type of cruelty which you will hear of was beyond her, Backhouse said. She regularly took part in the selections for the gas chamber, made up punishments of her own, and when she came to Bergen-Belsen she carried on in precisely the same way. She too specialised in setting dogs on people. She had made three statements. You will see how they vary. Do not believe a word she says in her defence, Backhouse warned. Irma Grese became the press’s favourite because she was blonde, with more than a hint of sexual titillation accompanying the report that she was Kramer’s lover.

Ladislaw Gura, a Bergen-Belsen Blockführer, against whom evidence of at least two murders would be brought. Schreirer, Heinrich, commander of Block 32. Then, again, you will hear of his regular cruelty.

Those were the SS members from Auschwitz. Three other women were charged with crimes committed at that camp: Ilse Lothe, Hilde Lohbauer, Stanisława Starostka, but these weren’t SS guards. They were prisoners, each a Kapo, each cruel and wicked, deeds without name, secret, black and midnight hags all, Backhouse might have said.

And then he came to Bergen-Belsen and the kitchens. If you want to imagine how despicable were the conditions and the treatment of the inmates then you will hear about the actions of Klippel, Flrazich, Mathes, Pichen, Barsch, Ida and Ilse Förster, Haschke, Lisiewitz and Hempel, Backhouse said. They behaved callously towards the inmates, proof of concerted action to harm the prisoners. Men and women of terrible character. With faces to match.

There were some others, the rump, SS Blockführers Otto and Polanski, administrators Schmedidzt, Egersdörfer, Opitz, Charlotte Klein, Bothe, Frieda Walter, Fiest, Sauer, Hahnel, Kulessa, Ostrowoski, Stärfl and Dörr and more Kapos: Burgraf, the almost Neanderthal-looking Erich Zoddel, Schlomowicz, Aurdzieg, Roth, Koper.

No details of their crimes yet. These would come. It was enough to look upon their faces lined up in the dock to understand their wickedness. My God, the prosecutor seemed to say, they look evil, don’t they?

As far as the charges against them were concerned, the panel of officers, and perhaps the audience too, had only to be convinced that criminal conditions of abuse existed in Bergen-Belsen and in Auschwitz, and the prosecution would have proved their case against each and every offender.

By the end of the first day, Backhouse had introduced each of the forty-eight defendants by name and outlined their association with particular crimes. Only once was the word ‘Jews’ used and that only in the context of saying, ‘You will hear that 45,000 Greek Jews were taken to that camp [Auschwitz], and when they were evacuating the prison only 60 were left.’ Otherwise the victims were not categorised. Why these people were killed in this way was unexplained.

No one in the press reflected on the omission. ‘Beasts of Belsen Taste British Justice’ was the headline in the Daily Mail.5 Edwin Tetlow, special correspondent, who’d been with the troops when they entered Bergen-Belsen, followed this up:

Josef Kramer, the ‘Beast of Belsen,’ and his 43 associates from Belsen and Auschwitz concentration camps sat for hours like so many pale, grave-faced automata under the floodlights in a converted military gymnasium here today. Their mass trial as war criminals, a spectacular curtain-raiser to the coming proceedings at Nuremberg against [Goering] and the rest of the Nazi big-fry, had begun.

Indeed, Justice Robert Jackson was just then calling a press conference to announce that the Nuremberg trial would begin by the winter and to confirm that the twenty-four major Nazi figures already identified would be the defendants.6 But for now, after Kramer, Irma Grese was the biggest draw. In one sense she was the attraction. Tetlow couldn’t help but convey her appeal. ‘She was the handsomest person in court,’ he wrote, ‘even without make-up, though there were faint, dark circles under her hard grey eyes.’ Then in bold print:

She had carefully brushed and groomed her hair for today’s first appearance and she had given herself a splash of colour by putting on a light blue blouse beneath her drab grey-blue tunic.

The character of reporting didn’t improve. On 25 September, Tetlow wrote:

Witness after witness is now being called upon to walk up and down before the dock and identify as many of the prisoners as he or she can. Something approaching fear is beginning to show in the pale tight-lipped faces of some of the women as they are picked out again and again.

But Irma Grese, the sullen blonde, remains unaffected as she stares out the witnesses and contemptuously obeys the court’s command to stand up and sit down in her turn. Kramer, too, is unmoved still. In fact, he often smiles as an accusing finger is pointed straight as a die at him.7

The Times was more reserved. It avoided dramatic banner headlines. ‘Colonel Backhouse, for the prosecution,’ it reported, ‘began quietly to retell with additional dreadful details the story of the two concentration camps, [and] though the story was well known to everybody present and to most of the civilised world outside, it had not lost its power to conjure up horror, pity, and anger.’8 Auschwitz was named and so was Irma Grese, though without the titillation that permeated Tetlow’s accounts, the paper avoiding any sexual connotations. Instead, it gave its readership a sober and accurate rendition of the first day’s proceedings.

Defence lawyers often appear as heroic figures when it suits dramatists and novelists. The maverick but brilliant attorney who takes a hopeless case and defends the seemingly guilty is a stereotype adored in films and fiction. He or she is the embodiment of justice. The character of Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird perhaps best exemplifies the noblest traditions of those who practise law. It’s a romantic picture, of course, but weighted with those profound values that are supposed to define British (and American) justice. Prime amongst them is the belief that everyone is entitled to have professional representation in court. The principle is ingrained in law school teaching.

Several years ago I was in the US, in Virginia. Through some convoluted route that isn’t relevant to this story, I was visiting a team of lawyers. They were capital defenders. Their sole job was to represent people on death row, people who’d already been convicted of a capital crime, a particularly horrible murder usually, and had been sentenced to death. Those American states, like Virginia, that practised the death penalty nonetheless had sophisticated and long-drawn-out appeal systems that afforded the defence lawyers plenty of opportunities to challenge the verdict or the penalty.

I arrived in a town in the Appalachians in late March. It was a raw day and between the frost and the leafless forested hills I felt uncomfortable even before entering the office of the attorneys I’d come to visit. I suspected I would encounter something deeply challenging to my cosy life and my equally cosy principles. That turned out to be true. Before the introductions were cold I was asked to look at the crime scene photographs of a triple murder. The attorneys were representing the man who’d already pleaded guilty to the crime. Their client had been sentenced to death. They were concerned with his appeal. As I clicked on each image on the office computer screen, images which showed the bodies of the victims lying in their blood, in the middle of their home, their lives ended in immediate and cursory fashion by the man they thought to be their friend, a man who was disturbed, ill-educated, with a troubled and gun- and alcohol-riddled history, I couldn’t quite understand what I was supposed to feel. Being adamant that the death penalty was wrong, no matter what the circumstances, was enough to make me think the attorney deserved my support. But another voice asked: did that really require the most expert services that could be afforded? Did the self-confessed killer merit a brilliant lawyer who might be able to twist the system to his advantage?

My attorney host sat down with me in his office after I’d viewed all the photographs. ‘Horrific, aren’t they,’ he said, and he asked me what I thought. There was no point in dwelling on the terrible circumstances of the killing. The sequence of events had already been explained to me. So I said I admired the attorney for what he was doing. I was against the death penalty too, I said, and it was right that the accused should be given every assistance. The attorney shook his head. ‘It’s not about that,’ he said. ‘Whether the death penalty is justifiable or not isn’t the issue. If we ever became associated with that debate we’d be lost.’

The attorney explained his philosophy. His guidance came not from opposition. If anything the system was to be upheld. He might disagree with its operation and its penalties but it didn’t matter. ‘One of my most difficult tasks,’ he said, ‘is trying to persuade the defendant to appeal. Most just can’t face the prospect of life in prison. That’s their only alternative and it terrifies them.’

‘How do you get them to change their minds?’ I said.

‘We have to show them that they still have a life they can lead, even in prison. I don’t know whether they’re convinced. But we usually get them on board.’

Perhaps I should have asked not how but why they persuaded these people to fight their sentence of death. I imagine the answer would have been that life is sacred, and that the system shouldn’t be allowed to end it without resistance. Whether that was the same thing as being against the death penalty, I’m not sure.

A few years later I spoke to one of the leading mitigation lawyers in the US, a remarkably vibrant and determined man called Russell Stetler, whose role is to coordinate advice to attorneys across the States representing inmates on death row. He said something that chimed with the sentiment of that Virginian attorney who’d shocked me with his images and, if I’m honest, his approach. Stetler said, ‘Everything I and my colleagues do is premised on one belief: that someone is more than the worst thing they’ve ever done.’ And that meant even the most heinous offender should be heard, perhaps understood and given the chance of redemption.

Thinking about those men and women sitting in the dock at Lüneburg, all those accused whose testimonies I’d read (and there are hundreds) from courtrooms across Germany, in Hamburg and Wuppertal and Hannover, I wondered how much I could give credence to the sentiment: they are, were, more than the worst thing they’d ever done. And thus they are, were, deserving of representation by a skilled advocate. I wondered, too, whether Major Winwood and Major Cranfield and the other defence lawyers believed the same. Did they defend those people, who as far as I could tell had spent years doing the worst things they’d ever do or anyone could ever do, for such principled reasons?

On 25 September 1945, the Daily Mail published a letter in its ‘Brickbatz, bouquets, and viewpointz’ section from a Miss Turnbull of Berwick. She had been moved to write on the horrors of Bergen-Belsen which she’d heard about over the radio and in the newspapers and said primly: ‘It is extremely surprising, therefore, to read that British officers are apparently willing to “defend” those guilty of, or responsible for, those atrocities … simply because the “Belsen beasts” have chosen them.’

The editor responded: ‘Indignant reader Turnbull should remember that Belsen trial serves secondary purpose as example to Germans of democratic legal process. Long proud tradition of British justice is that accused persons have right to choose their defenders.’

Curt prose it might have been, but it also reflected the fundamental principle I encountered in Virginia. Some criticism was directed at the lawyers defending the Nazi war criminals (Thomas Winwood expressed surprise and I think sadness at the attacks made against him in his all too brief and unpublished recollections which I read amongst his papers), but it wasn’t prevalent in the British press.

That might have had something to do with pressure being exerted from the War Office. Towards the end of the trial, a memo was issued from the army in Germany which noted ‘the disparaging remarks’ appearing ‘about the defending officers’. It requested the President of the Court to make a public statement affirming that ‘NONE of the defending officers volunteered to defend any of the accused’, ‘no option was given to any of the officers as to whether they would undertake the defence or not’, and ‘the case has been tried in accordance with the principles of British justice, one of which is that an accused person should have every reasonable facility for putting up his defence’.9 If these retributive trials were to define the difference between ‘us’ and ‘them’, between the Allies and the Nazis and all they stood for, then fairness had to be maintained and that meant representation by a skilled lawyer. I had to remind myself of that many times. Major Winwood and the other defending lawyers tested that proposition to the limit. Not by the fact of their representation, but by their willingness to adopt any argument in defence of their clients. Major Cranfield, representing Irma Grese, made a suggestion that seemed petty, ill-judged, fundamentally insulting to the obvious crimes of the Nazi concentration camp system. He said that the camps were ‘legal institutions’ under German law. The Times reported the argument’s conclusion: ‘A German working there could not be expected to deny his own law or to judge the camps by the standards of international law’,10 and thus couldn’t be guilty merely by reason of service. The newspaper didn’t condemn the argument, it merely repeated it. Cranfield’s lawyerly point incensed many. Later, commentators used it to doubt the integrity of proceedings, an indicator of how proper process had overshadowed justice. An insult to the memory of the victims.

Defending the indefensible may be inherent in the principle of fair trial, but once adopted, only counter-argument and perhaps established rules of procedure can properly intervene to limit the scope of the defence. Whether it was palatable or not, those acting for the perpetrators on trial were free to defend as they saw fit. And they hammered at each and every prosecution witness, claiming fabrication, mendacity, distortion, exaggeration. If witnesses hadn’t seen the events they were testifying to directly, then they were attacked for relaying hearsay. All standard legal tactics.

It was a very blunt instrument, nonetheless. And given that the prosecution was trying to establish that a criminal regime existed and bringing evidence of the culture and environment at Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, the testimony followed suit. Often, it was simply vague. How else could it be when a victim witness had seen abuse and death day after day after day? Every suffering merged into one long, torturous experience. Moonlit sharpness of memory was rare. And any imprecision provided even more ammunition for the defence.

Like many of the prosecution witnesses, Dora Szafran was young, twenty-two years old, Jewish and from Warsaw. She’d been arrested on 9 May 1943, was taken to Majdanek to begin with, then transferred to Auschwitz in June of that year before finally being transported to Bergen-Belsen in January 1945. When Col Backhouse asked her why she’d been arrested by the Germans initially, Major Cranfield objected. He said the question was irrelevant, not a part of the charges and it might prejudice the defendants. Witness after witness, he said, had been asked the same question.

And indeed they had. Anni Jonas from Breslau, arrested and sent to Auschwitz in 1943; Sophia Litwinska, from Lublin, arrested and sent to Auschwitz in 1941; Ada Bimko from Sosnowitz, sent to Auschwitz 1943; Ilona Stein was from Hungary and transported to Auschwitz in June 1942; Hanka Rozenwayg lived in Vokhin, Poland, before being arrested and shipped to Auschwitz in the summer of 1943; Lidia Sunschein; Estera Guterman; Paula Synger; Ruchla Koppel. Each had been asked by the prosecution why they’d been taken away by the Nazis. And each one had said, ‘Because I am Jewish.’ Cranfield’s objection was that the reason for their arrest would reflect badly on the accused, would suggest that the defendants were conspiring in the persecution of the Jews and were therefore integral to the systems of hate and extermination that infected the whole Nazi state. Given that Backhouse could barely bring himself to mention the Jews in his opening statement, at the very moment when he had the ear of the world’s press, that he chose not to highlight the persecution of the Jews as a major part of the prosecution’s case, it was odd that the matter was filtering into proceedings in this backhanded way. Was he trying to condemn by inference?

Of course he was. That was why the defence attorneys objected. But if so, it seemed a little strange to be coy over this aspect when every other systemic abuse was accentuated so as to reinforce the charge that the defendants were part of a single evil enterprise.

Major Cranfield’s objection was quickly dismissed, though, and Col Backhouse took the opportunity to say that his case was founded on the principle that the laws of war required no detainee to be ill-treated because of their religion. And he asked again, ‘Why were you arrested?’ and she replied, ‘Because I am a Jewess.’

Szafran showed to the court a large and deep scar on her arm. After she was tattooed on arrival at Auschwitz one of the Kapos had struck her. But this was incidental to her evidence. She told of the ‘selections’ for the gas chambers. They were carried out, she said, by Kramer, Klein and Dr Mengele. Grese was there too, she said, pointing to them as she was allowed down from the witness box to parade in front of the dock and scan the ranks of accused. She could identify Johanna Bormann as well, the woman SS member who she’d seen setting her dog, she thought an Alsatian, on an inmate who’d been unable to keep up with a work party, pushing the dog to tear at the victim’s throat. She didn’t know whether the prisoner had died.

But the bulk of her evidence focused on the ‘selections’. She heard the shouts and shrieks of those sent to their deaths. She said Kramer beat people so often that she’d lost count of the number of times. Grese too, using a stick, a riding-crop type of implement, she was not quite sure. Then, whilst at Bergen-Belsen, she said she’d worked in the kitchens. She saw another of the accused, Karl Flrazich, an SS-Rottenführer (who one inmate, Frenchman Raymond Dujeu, described by contrast, in a short deposition taken by Major Smallwood early in the investigation on 8 May 1945, as an ‘exception to the ordinary guards and always kind and never beat anyone’), fire out of the window of the kitchen at the prisoners the day before the British liberation, killing several, maybe as many as fifty, she said. There were no reasons for the shooting as far as she could tell, unless it was revenge.

The cross-examination began. Major Cranfield requested permission for the witness’s scar to be inspected by a medical officer. Did he think she was lying? Did he think that he could make her look foolish by showing that her wound might have been caused other than how she’d told the court? The request was granted and a British Army doctor called upon by the defence advanced to the witness box and examined Szafran’s scar. He then retired (to consider his opinion?) and for the moment the scar was forgotten. The witness was left to answer questions from the defence lawyers.

Major Winwood was first in line. He challenged Szafran’s memory and her veracity. His aim was to establish that his client, Josef Kramer, hadn’t taken part in any beatings, that he was an honourable soldier forced to do a job against his wishes, but who’d undertaken duties at both camps with as much care for the prisoners as he’d been allowed. The witness was adamant she’d seen the commandant at many selections. Winwood didn’t challenge her, as though he’d accepted that he could only defeat the evidence of gassing through legal argument. There was no point in suggesting Kramer hadn’t been there. Kramer had already confessed to his presence on the Auschwitz ramp where Jews had been subjected to selection for the gas chambers on disembarking from the trains. In September, a couple of weeks before his trial was to begin, Lt Col Genn had taken another statement from him. Instead of denying any knowledge of mass killing, he confessed liberally.

The first time I saw a gas chamber proper was at Auschwitz. It was attached to the crematorium. The complete building containing the crematorium and gas chamber was situated in Camp No. 2 (Birkenau) of which I was in command. I visited the building on my first inspection of the camp after being there for three days, but for the first eight days I was there it was not working. After eight days the first transport, from which gas chamber victims were selected, arrived and at the same time I received a written order from Höss, who commanded the whole of Auschwitz Camp, that although the gas chamber and crematorium were situated in my part of the camp, I had no jurisdiction over it whatever. Orders in regard to the gas chamber were, in fact, always given by Höss and I am firmly convinced that he received such orders from Berlin. I believe that had I been in Höss’s position and received such orders, I would have carried them out because even if I had protested it would only have resulted in my being taken prisoner myself. My feelings about orders in regard to the gas chamber were to be slightly surprised and wonder to myself whether such action was really right.

The qualified confession was enough for Winwood to focus his cross-examination on Szafran’s memory for specific instances of violence allegedly committed by his client. He had to present a picture of a man uncomfortable with his role, who’d only looked on and hadn’t joined in with the violence. It was a hopeless task.

Had she seen Kramer beat anyone?

Yes.

Could she describe any such occasion?

In Auschwitz, she saw a prisoner lose her shoe just as they were passing out of the gate in her work party. Kramer beat her with a stick as he was standing by the gate.

When was this?

End of 1943, beginning of 1944.

And in spite of the distance of time, you can still remember the full details of that one incident?

Yes. Emphatically. She could not possibly forget, she said. And Major Winwood sat down. Maybe he was satisfied that the story hadn’t revealed anything more ghastly than a beating.

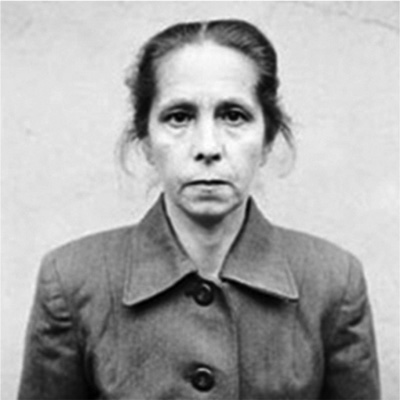

The other defence attorneys probed her stories too. They asked for more and more detail. The exchanges were painful in their dissection. The account of Johanna Bormann setting her dog on a prisoner was Major Munro’s concern. Bormann was his client. She was fifty-five years old and had joined the SS in 1938. Her first major concentration camp posting had been to Ravensbrück. By 1943, she’d been transferred to Auschwitz II-Birkenau. Like so many others, she’d found herself evacuated to Bergen-Belsen in the early months of 1945, where her job was to look after the pigsty. She was thin, her cheeks depressed. Photographs of her taken on her arrest showed a woman who looked mean-lipped and pinched. But, then, what picture of any accused presents a comforting and pleasant face?

Munro wanted to know from Szafran how many people had seen the incident with the dog, how far the witness was from the incident, and then he attempted to push a different version of the story, a wholly benign interpretation.

‘Is it not the case,’ Munro asked, ‘that the dog escaped from the guards’ control?’

Szafran said, ‘I saw it with my own eyes, and the woman boasted about it to an Arbeitsführer afterwards.’

‘Is it not the case that the woman who was attacked broke the ranks?’

‘It was already in the Lager, and I mentioned that the woman had a swollen leg. She lagged behind and that is what happened to her.’

‘Is it not the case that the woman who had charge of the dog tried to stop it from attacking the other woman?’

‘When the dog went for the woman’s clothes she rebuked it and urged it to go for the woman’s throat.’

‘Is it not the case that the woman who had charge of the dog put her hand on the throat of the other woman to shield it against the attack?’

‘As I am saying for the third time, she commanded the dog to go for the woman’s throat to choke her to death.’

For those few minutes when the various questions were being put all context was lost. The camp and its barracks and Appellplatz, its work parties and barbed wire, its stench and roughness, its timeless violence, all were momentarily dispatched and the only things that existed were the question and the answer. Give more detail, describe more clearly, unpick each statement, each scarred memory, and if the witness can’t do this with fluency and total recall then doubt is cast by faulty recollection.

Major Cranfield asked Szafran to say more about the stick she said Grese used to beat inmates: describe the riding-crop, he asked. It was made of leather, she said. But yesterday she couldn’t remember the stick was made of leather: why not?

‘I put it to you,’ said Cranfield, ‘that you’re hopelessly confused about this beating.’ She’d been colluding with other witnesses, hadn’t she? And Cranfield finally came back to the scar on her arm. He said she should have gone to the camp hospital to get the wound treated, that the scar wouldn’t have been prominent if she’d sought medical attention. Cranfield implied that the Auschwitz hospital was like a doctor’s surgery: if not inviting and comforting then at least able and ready to administer health care. Had he not been listening to the evidence?

By the third week of the trial, irritation infected the courtroom and those who observed the proceedings. ‘The wheels of the law are grinding exceeding small,’ said the Manchester Guardian.11

Reading trial transcripts is a painstaking process. It has to be. But it’s an imaginative one too. You can’t help but infuse the words with voices, with character. For all the potential for variety of human life that this implies, the Belsen transcripts, or at least the questioning at Lüneburg, relentlessly minute and focused, was depressingly familiar. I’d come across the same line of enquiry many times. The 2006 court martial in Britain of seven British troops for the ill-treatment of Iraqi civilians in an army base in Basra depicted in A Very British Killing hardly deviated in style or content. Remarkably, though perhaps for some reassuringly, given the institutionally asserted enduring quality of ‘British justice’, the tactics and language were almost identical: disregard the context, the defence attorneys would say, fix your eyes on the lies instead, on the exaggerations and inconsistencies. That was the tactic in 1945 in Lüneburg and it was the same sixty years later in Bulford court martial trial centre in Wiltshire.

Was the comparison valid?

When I read Winwood’s and Cranfield’s and the other defence lawyers’ cross-examinations, I thought it might be. Not because of the content but rather because of the style of lawyerly performance. It was ripe for parody. When Slobodan Milošević, Serbia’s erstwhile president, was accused of crimes against humanity and genocide committed in the wars in Kosovo and Bosnia and Croatia during the early 1990s, and stood before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia at The Hague, he decided that he would take that defence lawyer role for himself. He delighted in sitting alone at his desk, earphones strapped across his head, files before him, a panel of judges to his front, several ranks of prosecution lawyers to his flank, entering this valley-like arena as though he were a heroic defender of a nation. It was an image the world could see and Serbia could see, the proceedings streamed on TV channels as it developed into an epic soap opera. He used the opportunity to cross-examine witnesses as a political coup de main, striking at ‘the West’ with each spearing question. Or at least, he appeared to do so by the wit of his questions and the sharpness of his recall and the audacity of his posture (he refused to stand up when addressing the court as all the other lawyers in the room were required to do, and he insisted on referring to the senior judge only as ‘Mr May’ instead of ‘Your Honour’, thus adopting and resisting the polite conventions of this theatre at the same time).

Milošević became so successful in the drama that the prosecution had to intervene. They applied for some witnesses to be exempt from his cross-examination. Two women raped in the conflict, whose written testimony, given at another trial, had been presented to provide the court with evidence of sexual violence amounting to crimes against humanity, should be protected from the defendant’s questioning, the prosecution argued. The judges agreed. Cross-examination ‘should not be permitted mechanically and as a matter of course’.12 Provided the rights of the accused were protected sufficiently, the veracity of the witnesses’ evidence having already been adequately tested in the previous proceedings, there was no need to subject them to the trauma of living through their ordeals again.

That aside, and it was an exception, Milošević played the court with bombastic ease. His demeanour and delivery must have been stimulated by all those clever lawyers he mimicked or mocked. With one anonymous witness, referred to as Number 1011, who made a statement about an action in the war in Brčko and was brought to the trial because his evidence was contentious and the defence were entitled to test it, Milošević picked at him for hours. He called him ‘Mr 1011’.

‘You say that the war in Brčko began in the night of the 30th April and now you say that it began on the 4th May. You say actually in your statement that it was on the night of the 31st April. The 31st of April does not exist.’

Milošević wouldn’t let the idiotic little error drop. He referred later to the war that began on 31 April, deep sarcasm permeating his questions. And he continued to hunt down little mistakes whenever he could. It was precise and sort of clever, dissecting each witness with the same intense and well-briefed scrutiny. A ‘tour de force’, some would call it, though it was more a ‘tour d’imitation’, a mockery of the British lawyer’s art. With the chief prosecutor of the case being a British QC of long standing, Geoffrey Nice, the synthetic was matched against the real in every session. But Milošević didn’t fare badly by the comparison. Was he an inspired advocate who could have been a brilliant barrister? Or was the lawyer’s job easy to replicate for a politician well versed in antagonistic debate?

Milošević’s trial was ‘fair’ by most accounts and that was how an advocate was supposed to behave in a fair trial. Whether Bergen-Belsen, Nuremberg or The Hague, we have one form to fit all circumstances. If that invites mockery, as Milošević was wont to do and others have too, then that’s unfortunate. Perhaps it doesn’t matter whether defendants can exploit the form of trial for their own amusement. A more pertinent concern might be that the form is flawed if its purpose is to discover the truth of a person’s suffering and an accused’s guilt. Milošević wasn’t subverting the process: he was simply playing the game. His might have been a pedantic and irritating performance, one which any good professional lawyer might ridicule, but he was acting little differently from those lawyers at Lüneburg casting every doubt they could on the testimony of all witnesses brought before the court. It might be fitting for a solitary crime, where the evidence is tested to establish what happened and who was culpable. But with witnesses brought only as representatives of thousands of victims, with a whole institution of abuse under scrutiny, with dimensions of harm transcending any one moment, extending across years and locations and casts of perpetrators, was it appropriate? Was it fair to victim, witness and accused alike?

There was an evident problem with the Belsen proceedings. It stemmed from the inadequacies of the investigation. Though hundreds of witnesses had given their testimonies to the British investigators, once interviewed no one kept close track of their movements. Bergen-Belsen camp remained alive, with tens of thousands of survivors recovering but also desperate to leave. Who would want to stay in that hell-hole?

Over the four or five months from liberation to the trial good witnesses had been allowed to disappear. Many had left, to return to their homes. They’d scattered across Europe, to Prague, Hungary, France, too far to chase after and bring back to Lüneburg.

After presenting all his ‘live’ witnesses, Colonel Backhouse wanted to ensure that all the evidence collected from the investigation was put before the court. He gave assurances that he’d done his best to bring the witnesses to the hearing, but it hadn’t been feasible in many cases. He still wished to rely on the evidence in their original sworn statements. The prosecution team had compiled a thick book of witness depositions, dozens of them, and he wanted the court to accept them as further evidence against the defendants.

One of the defence lawyers, Captain Phillips, objected. ‘In our submission the whole of the evidence contained in this book is completely unreliable, thoroughly slipshod, and incompetent.’ It was worthless, he said.

But Carl Stirling, the Deputy Judge Advocate, ruled that the book of statements would be admitted, though the court would have to weigh the value of each witness account with caution, and they would have to be read out aloud to the court, one by one, so everyone could hear. The defence could object to any part and then they’d see whether to accept the statement or not.

And so began a long recital. Fortunately, many of the accounts were brief. Ridiculously so, again reminding the court that the initial investigation was deficient. Dora Almaleh’s was the first. It had been written down by Major Champion, then second in command to Lt Col Genn, now leading No. 2 War Crimes Investigation Team. This was its extent:

1. I am 21 years of age and because I am a Jewess I was arrested on 1 April, 1942, and taken to Auschwitz Concentration Camp where I remained until I was transferred to Belsen in November, 1944.

2. I recognise No. 2 on photograph 22 as an SS woman at Belsen. I knew her by the name of Hilde. I have been told now that her full name is Hilde Lisiewitz. One day in April, 1945, whilst at Belsen I was one of a working party detailed to carry vegetables from the store to the kitchen by means of a hand cart. In charge of this working party was Lisiewitz. While I was on this job I allowed two male prisoners, whose names I do not know, to take two turnips off the cart. Lisiewitz saw me do this and pushed the men, who were very weak, to the ground, and then beat them on their heads with a thick stick which she always carried. She then stamped on their chests in the region of the heart with her jack-boots. The men lay still clutching the turnips. Lisiewitz then got hold of me and shook me until I started to cry. She then said, ‘Don’t cry or I’ll kill you too.’ She then went away and after 15 minutes I went up to the men and touched them to see if they were still alive. I formed the opinion that they were dead. I felt their hearts and could feel nothing. They were cold to the touch like dead men. I then went away, leaving the bodies lying there, and I do not know what happened to them.

3. I recognise No. 1 on photograph No. 5 as an SS man at Belsen who was in charge of the bread store. I have now been told that his name is Karl Egersdörf[er]. One day in April 1945, whilst at Belsen, I was working in the vegetable store when I saw a Hungarian girl, whose name I do not know, come out of the bread store near by carrying a loaf of bread. At this moment Egersdörf[er] appeared in the street and at a distance of about 6 metres from the girl shouted, ‘What are you doing here?’ The girl replied, ‘I am hungry,’ and then started to run away. Egersdörf[er] immediately pulled out his pistol and shot the girl. She fell down and lay still bleeding from the back of the head where the bullet had penetrated. Egersdörf[er] then went away and a few minutes later I went and looked at the girl. I am sure she was dead and men who were passing by looked at her and were of the same opinion. The bullet had entered in the centre of the back of her head. I do not know what happened to her body.

Sworn by the said deponent Dora Almaleh at Belsen this 13th Day of June, 1945.

(Signed) Dora Almaleh.

Captain Brown was Karl Egersdörfer’s lawyer. He objected to paragraph 3 being admitted. He said the general charge against his client was for war crimes committed against Allied nationals. He said the victim described in paragraph 3 was Hungarian. A war crime could not be committed by a German against a Hungarian, he said. They had been on the same side.

In reply, Colonel Backhouse argued that Hungary ceased to be allied to Germany before April 1945 and had then joined the Allies to ‘some extent’. Besides, he said, he was trying to show how people were treated at Bergen-Belsen generally. Whoever was injured or killed was immaterial: it was enough to know that this was the nature of the regime. The paragraph was allowed to stay, though as the witness wasn’t there, she couldn’t be cross-examined. There lay a deep flaw in the prosecution’s preparation.

Egersdörfer was forty-three years old. He’d joined the SS in 1941 and had been sent to work in the cookhouse in Auschwitz. He was there nearly four years. Given that the prosecution had said, at the beginning of the trial, that the whole operation of the kitchens and stores was an affront to humanity, a means of perpetuating the suffering of the inmates with callously inadequate distribution of food, the general torment that each so-called ‘meal’ would represent for every inmate, one might have thought his position alone would have condemned Egersdörfer. But the case against him would come down to this affidavit of Dora Almaleh, nothing else. No other statement or witness would be brought against him. This one moment of violence was attributed to him and described by a witness who wasn’t in court. And Egersdörfer would deny any ill-treatment, let alone murder. The court would acquit him. Despite the prosecution’s claim that he was part of the KZ machine and that this affidavit said he’d killed someone unlawfully, some corroboration was needed. Someone had to stand up and say: ‘I saw him kill someone, beat someone.’ But that wasn’t to happen in Egersdörfer’s case.

There were nearly a hundred or so other depositions like Dora Almaleh’s.

Nineteen days had passed by the time all the prosecution witnesses had retold their stories and the depositions and statements had been read out to the court. It was then for the defence lawyers to frame their arguments. They and the watching press and locals, who’d come to hear what could possibly be said to excuse any or all of the accused, waited on Major Winwood as he was invited to make his opening address on behalf of Josef Kramer. He was also the lawyer for the doctor Fritz Klein, Blockführer Peter Weingartner and Lagerführer and cook Georg Kraft. But Winwood’s advocacy for these three other men would have to wait. Kramer came first. He was the most important figure, after all.

Winwood must have known that each word he uttered would be scrutinised and reported around the world. He must have known that all he would say would reflect upon him as well as his client. Did he care? Or did the shield that lawyers think protects them as mouthpieces for those whom they represent extend to him too? His speech wouldn’t be long by lawyers’ standards and he must have anticipated that the journalists present would repeat only those parts that stood out amidst the grey gloom of boredom that had inhabited the Old Gymnasium in Lüneburg for nearly four weeks. (Any interest of the local population had apparently already been exhausted – the Daily Mail said that only thirteen Lüneburg Germans had stayed throughout the afternoon session on 4 October, chatting amongst themselves, yawning and reading the local newspaper.)13 Despite this, Winwood erred.

By now it was clear that the defence were relying on the supposed ‘German’ culture and law of blind obedience to excuse everyone on trial. It was the foundation of his case, Winwood said, that Kramer was a member of the National Socialist party, was a member of the SS and, he said, was a German.

‘I would ask the Court when the time arrives for them to find their way through the maze of evidence before them to grasp that phrase: Kramer is a German, in the same way as Ariadne when she was making her way through the labyrinth.’

The classical reference disappeared rapidly, but the tenor of argument was consistent. The German state, the German law, was the Führer. Obedience was absolute and that principle was enshrined in the law, in the oaths that Kramer was required to take when joining the SS, in the being of every German at that time. Winwood quoted from the Nuremberg Laws, he quoted Alfred Rosenberg (whom he and the other defence attorneys had visited in Nuremberg prison to confirm that no individual could feasibly deny the authority of the regime), Rudolf Hess, Robert Ley, all in custody a few hundred miles away waiting on their appearance at the Nuremberg trial, and of course Hitler himself, to confirm total obedience as a way of life and state. If Winwood was to be believed, there was no room for moral, let alone legal, choice. Kramer was a slave to the regime. He had to obey.

The line of argument became stretched when ‘the chimneys of Auschwitz’, as Winwood called them, were the result. Kramer wasn’t just a German watching on as the state carried out its policy of liquidating the Jews: he was the commandant of the extermination centre at Birkenau that was run to fulfil, to define, to refine that policy. He was at the core not the periphery. In his desperate attempt to overcome such a prejudicial realisation, Winwood made a ridiculous slip.

Commenting that Germany hadn’t invented the concentration camp (he reminded the court of British actions in South Africa during the Boer War and in Egypt, probably elsewhere too), Winwood said that the ‘object of the German concentration camp was to segregate the undesirable elements, and the most undesirable element, from the German point of view, was the Jew’.

Oblivious to the sudden opening of ground before him, he pressed on:

The type of internee who came to these concentration camps was a very low type and I would go so far as to say that by the time we got to Auschwitz and Belsen, the vast majority of the inhabitants of the concentration camps were the dregs of the Ghettoes of middle Europe. There were the people who had very little idea of how to behave in their ordinary life, and they had very little idea of doing what they were told, and the control of these internees was a great problem.

Winwood hadn’t finished. He couldn’t avoid the subject of the ‘gas chamber’. Instead he maintained the theme of obedience. And for this Winwood had to find someone, virtually anyone, to whom he could point as having a superior or more responsible position that would allow Kramer to claim subservience. So he turned to Rudolf Höss, the commandant of Auschwitz No. 1 (Birkenau was Auschwitz No. 2). Höss, he said, was in overall command of the whole complex. It was he who’d ordered the selections and the gassing of those chosen to die. Winwood said:

Now to return to the gas chamber. It existed, there is no question about it. There is very little question about its purpose, its purpose being to remove from Germany that part of the population which had no part in German life. The way it was done, we have heard from several witnesses, was by selections, selections which took place at the station when the transports arrived, and we have heard also of selections which took place later on inside the camp. These selections were ordered by Höss and later by the commandant who relieved him. They were presided over – and this is the Defence’s line – invariably by a doctor. All doctors in Auschwitz were under the direct control of Auschwitz No. 1. The head doctor and all the other doctors lived in Auschwitz No. 1, and all hospitals in these areas and all doctors, and everything connected with the hospitals, was directly under Auschwitz No. 1. Present at these selections were certain SS people. There were large numbers of transports coming in, and it is quite obvious that a certain amount of control was needed. When one thinks that a lot of these people knew what they were coming to Auschwitz for, I think it is fair to say that a good deal of control was needed when they arrived.

It so happened that these transports came in to Birkenau. They came into Birkenau, Auschwitz No. 2, because in that camp was situated the gas chamber. That was a misfortune for Kramer, because he held that job, was commandant of that part, and as commandant he will tell you that he received instructions from Höss and that he was responsible for law and order on the arrival of the transports and for the control during the selections. There have been allegations against Kramer and against various other people belonging to the camp that they took an active part in those selections, and there have been allegations that they themselves actually chose victims for the gas chamber. Kramer will tell you that he never once chose a victim for the gas chamber. He will tell you that he took no active – if by ‘active’ is meant helping – part in choosing people for the gas chamber. He will tell you that a physical selection was done by doctors to decide which people were capable of working for the German Reich, and that would only be done by doctors.

So, there was the defence for his time at Auschwitz: Kramer had been unlucky. Unlucky to be sent to Auschwitz rather than the Eastern Front as he’d desired. Unlucky to be given command of a whole camp within the gigantic and dispersed compound. Unlucky that his camp should have included the gas chambers and crematorium. Unlucky that he should have had the job of overseeing the selection of new arrivals to die or to live a little longer to work. Unlucky that some of those who’d arrived, knowing what was in store, resisted their fate and, therefore, had to be ‘controlled’. Unlucky. Höss was the man responsible, the doctors were responsible, by implication even Dr Klein, who served with Kramer at Auschwitz and came with him to Bergen-Belsen, whom Winwood was also representing and who sat next to Kramer in the dock. (Of course, Winwood had a similar defence prepared for Klein: he would say briefly and simply in a couple of days’ time that though Klein had been one of the doctors who’d made the selections, ‘those capable of work and those incapable’, ‘there was no question of not carrying out that order; there were lots of other doctors there who would have done it if he had refused and been sent to a gas chamber himself’.)

That was Winwood’s line. Even allowing for the benefit of hindsight, it’s difficult to believe he could have thought this was sensible. The language, the inferences, the argument, were an affront.

The executive committee of the Board of Deputies of British Jews protested as soon as they heard reports of Winwood’s speech. So, too, the World Jewish Congress. Winwood ‘besmirches the memory of millions of men, women and children who died under unspeakable horrors, or were murdered for no other fault but that they were Jews’, the Board of Deputies telegraphed the President of the tribunal, Major General Berney-Ficklin. They said his remarks were ‘an insult to Jewry’, ‘vile and clumsy’. ‘The unwarranted slur cast by the defending officer on countless Jewish dead and their surviving brothers and sisters all over the world is a gross violation of British fairness and transgresses the just limits of British advocacy,’ the telegram added.14

I wasn’t able to discover much of Major Winwood’s career or life after he’d finished the Belsen trial. Unlike many of the lawyers involved, who cropped up in the obituary columns or became senior members of the Bar or the legal profession, Thomas Winwood returned to country practice as a solicitor in Britain. I knew he was a partner in a firm of solicitors in Salisbury. I knew he died in Bournemouth on 18 September 2005 and that various papers of his relating to the trial were deposited with the Imperial War Museum, mostly annotated transcripts from his infamous trial appearance. Other than that, nothing. Perhaps he found no difficulty in telling clients and friends and colleagues that he was once the Beast of Belsen’s attorney. But I wondered whether he might have been somewhat circumspect after the statements he’d made in Kramer’s defence. Would he have felt shame at his callous assertions? Probably not. The short recollections I was able to read merely alluded to the derision he received from some quarters. The only explanation he mustered was predictable as the defence lawyer’s mantra: I was my client’s mouthpiece. I was speaking for him.

If Major Winwood’s defence of Kramer was hopeless for the Auschwitz charge, the same could not be said for the Bergen-Belsen element. He’d already set out in his opening address the line he wished to follow: that Josef Kramer took command of the concentration camp for only a short period when no one could have done anything to alter the terrible conditions there. With increasing numbers of prisoners being foisted onto the commandant each day, the position would have become untenable for anyone.

Kramer claimed that he’d done all in his power to alleviate the situation. A letter was produced. It was from Kramer to his superior in Berlin, Gruppenführer Richard Glücks, who was the Reich Inspector of Concentration Camps, the man in overall charge of the KZ administration. Dated 1 March 1945, the letter supposedly supported the defence’s argument. Winwood described it as the ‘very kernel of Kramer’s defence’. Though he couldn’t with any authority say it was genuine (there were suspicions that Kramer’s wife had provided the copy), he intended to rely on it as if it were.

Even if a fabrication, the letter registered the voice of a man who’d been at the forefront of Nazi atrocity. The language alone betrayed the deeply ingrained sentiments of the system.

Gruppenführer [the letter began], it has been my intention for a long time past to seek an interview with you in order to describe the present conditions here. As service conditions make this impossible I should like to submit a written report on the impossible state of affairs and ask for your support.

You informed me by telegram of February 23, 1945, that I was to receive 2,500 female detainees as a first consignment from Ravensbrück. I have assured accommodation for this number. The reception of further consignments is impossible, not only from the point of view of accommodation due to lack of space, but particularly on account of the feeding question. When SS Stabsarztführer Lolling inspected the camp at the end of January it was decided that an occupation of the camp by over 35,000 detainees must be considered too great. In the meantime this number has been exceeded by 7,000 and a further 6,200 are at this time on their way. The consequence of this is that all barracks are overcrowded by at least 30 per cent. The detainees cannot lie down to sleep, but must sleep in a sitting position on the floor. Three-tier beds or bunks have been repeatedly allotted to the camp in recent time by Amt. B. III, but always from areas with which there is no transport connection. If I had sufficient sleeping accommodation at my disposal, then the accommodation of the detainees who have already arrived and of those still to come would appear more possible. In addition to this question a spotted fever and typhus epidemic has now begun, which increases in extent every day. The daily mortality rate, which was still in the region of 60–70 at the beginning of February, has in the meantime attained a daily average of 250–300 and will still further increase in view of the conditions which at present prevail.