The Curiohaus is on Rothenbaumchaussee, a cultured, tree-lined avenue close to the centre of Hamburg. It’s a grand old construction built by a successful German merchant at the turn of the twentieth century, initially as a restaurant, then converted into a ballroom. The building remains a centre for dining and dancing and company events. In 1946, it was one of the chosen locations for the British-led war crimes trials. Over the course of a few months the Zyklon B, Bullenhuser Damm and main Neuengamme camp trials were held there.

Standing outside, I found it impossible to summon up the phantoms of that time, of those cases, despite my now heightened sense of the topography of atrocity fanning out across Hamburg from Neuengamme. Though I imagined contour lines connecting the concentration camp with the Messberghof, with the school in Bullenhuser Damm, with Fuhlsbüttel prison, even out across the countryside to the bay at Neustadt, and back to this pretty mansion house, none of those places seemed related to the prosperous, commercial facade in front of me. The Curiohaus had buried its past in the sleekness of corporate entertainment. No one wanted to celebrate the location of the British war crimes trials. Why would they?

It wasn’t a disappointment. I knew that if I was to satisfy my curiosity as to the nature of British justice delivered in response to all those investigations (a curiosity originally sparked by that picture of prosecutors I’d seen in the Neuengamme camp exhibition) I had to retreat to the documents, the transcripts, the written notes.

When I returned to Britain, I arranged for a prolonged stay at the National Archives at Kew, that place of quiet efficiency, conducive to study, with records delivered to a numbered locker within forty minutes of ordering, blue-jacketed stewards (as if on a sombre holiday from Butlins) watching over you, whispering in your ear should you mishandle the papers.

The contrast to the physical confrontations with concentration camp and killing ground seemed acute at first. But after hours reading about the British-led trials and investigations into war crimes and the Nuremberg proceedings running in parallel, I sank deeper into the quicksand of atrocity. The photographic evidence and witness testimony and the summaries of outrages darkened every day to the point where I could no longer focus properly. I would read until my eyes hurt and wonder not only at my capacity to absorb these stories but at how the investigators and prosecutors must have suffered from the bleakness of their task. What is it, I thought, to read account after account, statement after statement about the utmost cruelty? What is it to disinter the bodies of murdered comrades, hear the stories of the survivors? Should it provoke anger? Sadness that human beings can be so indifferent to the suffering of others? Whatever the emotions, I doubted they were positive. Even so, every file deserved scrutiny for the simple fact that the lives of men and women were in the balance.

When I took the Neuengamme files to my desk, I was surprised to find first amongst them a whole box of photograph albums confiscated by the British investigation team, page after page of snaps of laughing and posing German soldiers; one officer out for a walk with a woman and a pram, a sort of wheeled sled being pulled by a trio of dogs; a wedding portrait; a couple of soldiers sitting with beer glasses in front of them and between them a woman throwing her head back in exaggerated laughter; two SS officers, one with his arm draped over the shoulder of the other, their knees familiarly touching above the jackboots; a Christmas feast full of SS and their wives in 1944 (a few numbered in blue ink on the print, the numbers that would hang round their necks at their trial), spirits seemingly unaffected by the approaching end of the war; pictures of huts and construction workers, prisoners, a factory, an office, all lovingly labelled in German.

These were albums of happiness and normality, friends and colleagues enjoying life, in the snow, on bicycles, with their dogs, smoking cigars, marching with their units, mouths wide open singing. None were used as evidence. They were irrelevant to the proceedings, though they revealed more than any cross-examination I’d read so far.

I opened more boxes. There were several containing thickly filled lever-arched files. These were the Neuengamme KZ case transcripts. Here, I thought, I might find the answers to questions that had provoked me ever since that first visit to Hamburg, questions which were simply factual (how had all those inmates come to be on the Cap Arcona and the other ships in Neustadt Bay?) or ethical (who was responsible for their deaths?) or analytical (how did those British trials relate to the grand event in Nuremberg?), perhaps even psychological (what was it that had motivated those SS who’d whipped and executed and tortured seemingly without pity?). The folders holding the thousands of pages that recorded every word of the Neuengamme trial appeared as hermetically sealed containers which, when opened, would solve these mysteries.

Then I thought how strange it was that I could place so much trust in a typewritten script merely because it was neatly stored in files with official labels on their fronts and taken from the shelves of a storeroom in a national archive. There was a story there, though. There were many stories.

The fourteen accused sat in the readied courtroom, lined up in one long row, numbers hung around their necks, a small army of uniformed guards sitting behind them. The cards drawn tightly up to their collars were the means by which they were to be officially recognised, following the precedent set at the Belsen trial. It was easier that way when witnesses were asked to identify particular individuals. And it reduced these men below the status of any normal ‘accused’. For all the pretence that this was another criminal trial, you’d never see such numbering back at the Old Bailey.

Carl Ludwig Stirling entered. His reputation had been growing since the Belsen trial, where he’d acted as the Deputy Judge Advocate. He would be described a few years later by Ronald Clark, the author and journalist, as having become ‘that hawk nosed Dickensian Judge Advocate General who in 1945 and 1946 appeared in British military courtrooms like a shrivelling and avenging flame’.1 I found the article amongst Stirling’s private papers held at the Imperial War Museum. The passage had been underlined in blue pencil. Perhaps Stirling hadn’t appreciated Clark’s description, though his photographs did indeed show a balding, aloof, monocled man looking like an eagle waiting on its prey.

As with all his trials, he would maintain rigid control, a task made easier as there were no British barristers defending here, unlike at the Belsen trial. The German lawyers were a little more circumspect when it came to raising arguments in defence of their clients. Perhaps being citizens of a guilty country induced caution.

Above the Judge Advocate there was a balcony where the German civilian spectators sat and watched. As he listened to the opening of the case Stirling doodled. It was the same sketch which appeared scattered throughout his trial notes, punctuating those taken not only at Neuengamme but the other cases over which he presided. The drawing was a tiny and rough outline of a ship with a single funnel flanked by two cross rigged masts. There were a couple of protuberances from the foredeck, perhaps guns, perhaps some other form of rigging, it was hard to tell. A battleship, a cargo steamer? I had no idea. And I had no idea what it signified other than at times during these trials he was most likely bored. Which was understandable. Most legal proceedings have flashes of intensity when everyone within the courtroom will be so absorbed that they will never forget such moments. But these flashes are immersed in an ocean of monotony. Even when unpicking the extraordinary life of a concentration camp and its inhabitants the effect could be numbing.

Stirling was fresh from the Zyklon B case. That had finished only ten days before when Tesch and his manager Karl Weinbacher had both been found guilty and sentenced to death despite the absence of hard proof that either had known their product was used for gassing humans. One of the accused had been acquitted, though: Dr Drosihn. This is what Stirling had said about him in his summing up: ‘He is married and he has children, he is about forty years of age. There was some little reference to a slight sexual or moral kink which the man may have had, but I think we all agree that that should play no part in the assessing of Dr Drosihn’s integrity or reliability in the witness box.’2 And indeed it seemed not to have affected the decision.

Surprisingly, nearly all lawyers present in the Curiohaus, for the prosecution or the defence, were native Germans or Austrians. There was newly promoted Major Stephen Malcolm Stewart leading the prosecution case. He’d been involved in the Bergen-Belsen and Velpke baby home cases and had now been promoted to lead the Neuengamme prosecution. You might have thought from the name that he at least would have been a stalwart British citizen. But he was really an Austrian lawyer called Karl Stephan Strauss who’d only in the very month the trial in Hamburg began been given a British naturalisation certificate following wartime service in the Pioneer Corps.3 Like Walter Freud, he’d escaped from Austria shortly before the outbreak of the war, recognising the danger of the Anschluss and Nazi takeover of his country. Rather than stay and face certain incarceration and persecution for his political opposition, a stance that would have seen him almost inevitably interned in one of the camps that he was now helping to expose, he’d left his country and made his way through Poland and eventually to Britain. Stewart was assisted by Major Wein, another legal refugee from Austria.

All the defence lawyers were German. There were none of those willing British advocates, like Major Winwood, who’d caused so much antagonism with his ‘clever’ legal points on behalf of Josef Kramer at the Bergen-Belsen trial the previous year. And the defendants were German too. They looked calm and ordinary. Each was accused of the same familiar charge, that they, ‘between June 1940 and May 1945, when members of the staff of the Neuengamme Concentration Camps, in violation of the laws and usages of war, were together concerned in the killing and ill-treatment of Allied nationals being inmates of the same concentration camps’.4

It was the formula used in all the other trials that had been heard by British military tribunals over the past six months or so.

Whatever his nationality, Major Stewart began the case in English and in poetic style.

It was a hot summery day in May 1945 when a Lieutenant in the Reconnaissance Corps drove his tank through the streets of the village of Neuengamme. He was ordered by his Commanding Officer to go and see a hutted compound in which it was believed that there were thousands of internees and thought it had been a concentration camp. When he arrived … all he found was a black cat. Not until much later when some of the evacuated ex-internees returned and told a story and bit by bit like a jigsaw puzzle the full story of Neuengamme Concentration Camp through the years from 1940 to 1945 was put together.

He said this was not a case of ‘victors’ justice’. ‘Nothing could be more dangerous [than] to believe this was about the winners meting out revenge,’ he said, parroting the line taken by Justice Jackson in his opening speech at Nuremberg. Stewart then identified the most important elements of the crimes, all within the context of the KZ structure. He said, ‘The whole system was set out to achieve a complete debasement of the individual and one in the image of God was reduced to a state where they were much nearer animals than human beings.’ He mentioned the killing of the children subjected to TB experiments at Bullenhuser Damm, but kept the court’s mind fixed on the law.

I know sir that it is extremely difficult to restrain one’s emotions when human beings stoop to the depths of experimenting on and eventually liquidating innocent children, but I must ask you to view this piece of evidence the same as the rest of the evidence not with what may well be the justifiable anger of outraged humanity but in the cold and sober light of the law.

It was a little disingenuous. His subject matter aroused passion. How could it be avoided when listing the history of malice in such a camp? He told the court about the hospital, ‘one of the foulest aspects of the whole case’, and how the whole camp population of thousands would be crammed into the cellars of the two brick buildings when there was an air raid.

Can you imagine the scene? [he asked] Can you imagine the siren going and then these wretched creatures exhausted after a twelve-hour day staggering out in the dark, out of their huts being remorselessly bullied by their warders to run to the shelter and then when they reached the shelter, in the doorway falling over each other, stampeding, being beaten with rubber truncheons and kicked continuously down the stairs in the dark until eventually they reached the cellar where they were packed like sardines with no ventilation. There was something like 10,000 of them in those two cellars. It is a scene which is really too terrible to describe.

Stewart described it nonetheless. He likened it to the London Tube station disaster, raw in British imagination at least, a reference to the night of 3 March 1943, when 173 people were crushed to death in Bethnal Green Underground station as crowds poured into the makeshift shelter, seemingly panicked by the sudden firing of a nearby anti-aircraft battery, and the tripping of a woman that caused a chain reaction of people falling over each other down the long stairs. Stewart said such a crush was a nightly occurrence in Neuengamme.

Of course, the prosecutor couldn’t avoid embellishment, and however much he protested he couldn’t avoid the descriptions either. That was his job, to bring to life the misery and cruelty and protracted suffering of the camp. How else could he evoke the reality of the KZ if not through emotive language? He might have liked to bring it all back to the sober light of the law, but how ridiculous that was when you read his words. British criminal trials may be exercises in rational thinking, but to dismiss sentiment would be to deny the humanity that had been lost in the camps.

Stewart ended with a little story. It was another flourish that pandered to the press gathered at the back of the Curiohaus. He described how, after gassing a group of Russian prisoners one day, the SS called out the whole camp onto the Appellplatz. The bodies of the Soviets were dragged out on trollies and the assembled inmates were forced to sing:

Hail to thee, happy ambassadors,

a thousand welcomes, friends, be yours.

High honour to this day belong,

oh raise your sweetest voice in song.

‘This is typical of the sense of humour of the people before you,’ Stewart said.

At no time during his speech did Stewart mention Neustadt Bay and the ultimate fate of the Neuengamme prisoners.

It would take some days for Stewart to present the many facets of brutality. He had to provide a tableau of institutional and individual abuse. He had to show how the camp was deadly, designed to be so and administered with that purpose. He had to show that the men sitting in the dock were integral to the KZ where they worked, had committed acts of violence against prisoners and contributed deliberately to the killing and injuring and ill-treatment. The Belsen trial, where so many accused had been acquitted because of a failure to prove individual culpability, had put Major Stewart on guard. Witnesses were now brought who could point at the accused with certainty and say what they’d seen them do as well as describe the cruel nature of the KZ as a whole. It would take him thirteen days.

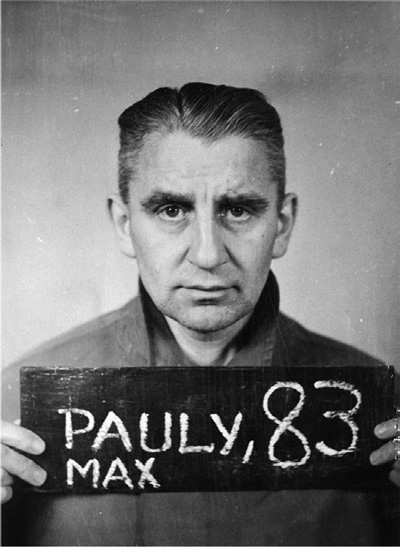

The first witnesses were those Major Till and his team had found recovering in Neustadt soon after the sinking of the Cap Arcona. Albin Lüdke knew the most as he’d been in the camp since 1940. He’d observed how the conditions and treatment had deteriorated over the years. He said Defendant No. 1, Max Pauly, was a ‘very bad commandant and his bad name preceded him’ before he arrived in July 1942 from Stutthof KZ. Prisoners who’d served time there ‘began to tremble when they heard that their former commandant was coming to Neuengamme’.

No. 2, Karl Totzauer, was the adjutant from 1944 but wasn’t seen much in the camp. Only when executions took place, special executions. Lüdke was asked to remember one. In October 1944, he said, about 800 Dutch prisoners arrived. Eighty of them were picked out, had their heads partly shaven and ‘were given an armlet saying “Torsperre”, which means they were not permitted to leave the camp’. These men were employed weaving mats in one of the cellars. By February 1945 there were only about 60 of them still alive. All were hanged in one go, even the ones in the sick bay, brought to the execution place on litters. That was when Totzauer would come.

Then there was No. 3, Anton Thumann. He was ‘a sadist in the true sense of the word. He liked to spend his time at beatings and executions, of which he was always the leader.’

All the others were described too. Each had his little violent foibles. Adolf Speck, Lüdke said, had first come to the camp in autumn 1943. His peccadillo was to be spiteful. ‘There were two ditches round the camp filled with water [for fire precautions]. When the inmates came in from work and did not march properly to attention, either because they were too tired or physically not fit enough to do so, then it was a great joke to pick out one or two or more and to throw them into these ditches filled with water.’ Lüdke had seen it happen. It wasn’t hearsay.

If these defendants were bad, Willi Bahr, Defendant No. 12, well known to the War Crimes Team now, was worse. ‘He was especially brutal, stupid and cruel,’ Lüdke said, confirming Bahr’s confessed speciality: killing inmates by phenol injection. He had seen him select men, take them away to the hospital and ‘after six or seven minutes I saw them carried out … into the mortuary’. He hadn’t witnessed any of the injections administered directly, but what other inference could be made? It was the same with the murder of two hundred or so Russians who’d been gassed by Bahr using Zyklon B. One day in the autumn of 1942, Lüdke had been in the workshop next door to the cells where Soviet POWs were kept. ‘When I passed the door,’ he remembered, ‘I saw that the door was open and a mountain of corpses in a cramped position and of the height of one metre 70 to one metre 80 was visible. In front of this mountain of corpses the commandant, Pauly, was standing, and also the then Lagerführer Luetkemeyer. These corpses were loaded on trucks.’ Everyone knew Bahr was the man who’d been the executioner.

And so he continued, itemising each cruelty he could recall, pointing at a defendant, describing the institution of suffering within which he had lived and seen thousands of others die.

Each defendant’s counsel stood to ask him questions, seeking to distance their client from any observed act of violence. It made for a long and dull process, attempting to distinguish between what Lüdke had seen for himself and what he’d heard from others. Even Judge Advocate Stirling intervened to pin him down. Lüdke was steadfast, giving example after example of the crimes he’d witnessed.

On Wednesday, 20 March 1946, the court travelled the short distance to Neuengamme to see the camp for themselves. Lüdke and another witness, General de Grancey of the French Army, were the guides. Everyone was there, the accused, their counsel, everyone. They exchanged questions and statements. They toured the buildings and factories and clay pits and barracks and crematorium. It was still a prison, except the inmates were now all SS or German officials. I could imagine that tour, now that I’d seen the site. It must have taken some time given its spread. But there was much to see.

Back in the courtroom, counsel for Willi Bahr, the man who’d killed so many in the hospital and whenever ordered, made an application: ‘It is my duty to ask the court to accept this plea of insanity.’

Stirling informed him that assertion of madness would be insufficient. He had to prove it, obtain expert psychiatric testimony. If that was to be his defence he had to prepare properly. That was English law.

The refusal seemed to sap the German lawyer’s enthusiasm for his application. ‘I myself think Bahr is not quite responsible for his actions,’ he said, ‘but I do not think he is quite insane; if you look at the accused you will see that he does not give the impression of a normal human being. I myself might even call it schizophrenia.’ He asked for a psychiatric report, but it would come to nothing. Bahr wouldn’t escape that easily and the witnesses came to tell of his role in the camp.

Joanneas Everaert was a Belgian, a twenty-five-year-old medical student arrested in July 1941 as a member of a socialist youth movement and the Belgian Resistance. He’d ended up in Neuengamme from September 1941 onwards, first working as a bricklayer and then from 1942 as a medical orderly. He’d been there until 1943 and then returned again at the beginning of 1944 until evacuation. He knew the camp doctors, Kitt and Trzebinski, and he knew Willi Bahr. He hadn’t seen Willi Bahr carry out the injections on prisoners, but he’d prepared the syringes for Bahr to use, filled them with phenol or strychnine or evipan, an anaesthetic, and had heard Bahr boast of his killings afterwards.

Then there were the TB experiments on the children. Everaert knew about them too. ‘At the end of 1944 I have seen 20 children arriving at Neuengamme camp. They were Jews, ten male and ten female.’ Two were French, one called ‘George’ and one called ‘Jacqueline’. He spoke with them several times. They’d been in good health when they’d arrived. But that changed with the TB experiments. He remembered Professor Heissmeyer visiting from Berlin, dressed as a civilian, spending a few hours at the camp and then leaving late in the evening.

It was the first witness evidence connecting the Bullenhuser Damm case with the main camp proceedings.

Other ex-inmates came to the court, identifying the accused where they could, distinguishing between what they’d heard and what they’d seen or experienced directly. The operation of the hospital was a key element in many of the testimonies, but the executions and general conditions in the camp were always a point of reference. It was the prosecution case that the camp had been run with an intent to eliminate the camp prisoners through work and through harsh conditions.

A small cadre of journalists and locals observed the case, but few others. There was scant press coverage. The newspapers back in Britain weren’t interested, not when the Nuremberg proceedings sucked what marrow there was out of public attention. How could Neuengamme compete, a camp that hadn’t been liberated to reveal heaps of corpses or packed crematoria or telltale stacks of shoes, teeth, hair, the detritus of unspeakable killing?

The writer Christopher Sidgwick was one of the few who stayed. He popped in now and then, absorbed despite the slowness of the process.5 The ‘immense detail’ and the interminable double and sometimes triple translation, from German into English into French and back again depending on the identity of the witness, set a plodding pace that tested the attention of everyone. But he had a special interest. He’d visited Dachau soon after Hitler and the Nazis had come to power, when the KZ system was relatively fresh and there were doubts in the British press as to the nature of these concentration camps: were they places of torture and death or not?

Sidgwick had toured the concentration camp outside Munich in February 1935. He had published a letter in the Manchester Guardian reporting on what he’d found.6 ‘The faces and carriage of the men as they went past me betrayed two things,’ he’d written, ‘lack of sufficient exercise and a continual terror.’ He’d described the poorness of the food (two beakers of ‘slop’ for lunch) and an officer who was ‘a sadistic bully’, but his only enduring complaint had been that the prisoners didn’t know how long they would have to serve there. Their sentences were rarely fixed to a specified term. Otherwise, according to Sidgwick, torture was ‘a thing of the past’, beatings were only a penalty for attacks on the guards, and the SS warders were on the whole ‘kindly, ordinary Germans doing their job as efficiently and considerately as circumstances permitted’.

Sidgwick had concluded, ‘I myself could put up with [the living conditions] … for some time,’ provided he knew that they would be temporary. The few inmates he’d spoken to didn’t have that luxury, but his impression at the time from both his inspection and a tour of the country had convinced him that ‘the fever of persecution and intolerance in Germany will continue to diminish at the slow and sure rate already apparent’.

Perhaps he was haunted by his acute misdiagnosis when he returned to Germany in 1945. He was one of those army officers (serving in the Royal Artillery) sent to Neuengamme to help transform the old KZ into an internment camp for German prisoners of war. On surveying the place to determine its suitability, he wrote that ‘standing before the deserted ovens in the crematorium, you became conscious of a primitive fear’.

One of the oven doors stood open. Projecting into the oven was a long metal stretcher, the length of a man, and on it were still the remains of human bones, charred to a chalky-grey gravel. All round the ovens the concrete floor was crunchy with these little fragments of bone. In the corner was a pile of urns, some already in cartons addressed to civilian cemeteries. It was a straightforward mail-order business.

I wondered whether Captain Sidgwick, as he then was, had embellished what he’d seen at Neuengamme. Lieutenant Charlton, the first British officer into Neuengamme, had said nothing in his statement about any carcass in the crematorium. The description of a floor crunchy with bones was highly effective too, but it wasn’t one that Charlton mentioned either. Charlton referred to the urns only. Everything, he said, was ‘clean and in good order’. Had he missed what Sidgwick said he’d discovered? Or was this Sidgwick’s way of capturing the waning interest of his readers? A little dramatic licence? The idea of having to embroider the truth of the camp seems absurd now, but then maybe commentators were struggling to maintain public disgust and horror. There had been so much after all. The facts and figures and photographs and film were everywhere. Nuremberg was replete with them. So how could people’s interest be sustained without some dramatic turn of phrase that required a slight alteration of the truth? Floor crunchy with bones. Carcass left in the oven stretcher. Images to make you start, to pay attention, to think: retribution is necessary.

If Sidgwick was to be forgiven for elaborating on the truth, assuming that that was what he’d done, then I suppose he could be applauded for his confession to a different sin. He wrote in 1946, when reflecting on the Neuengamme trial, that he’d felt the ‘contagious nature of hatred’, a human trait that he believed had consumed the Germans who’d worked in the KZs. During the five days he’d policed the intake of Nazi suspects interned in Neuengamme, time he said he and his colleagues had spent ‘hounding our prisoners’, he’d become aware that his own ‘regard for those men was dwindling to the same proportion as theirs had been for their victims’. It was something of a presentiment of the Zimbardo experiments to be conducted in Stanford a decade or more later, experiments that suggested few are immune to the insidious impact of power in encouraging sadistic propensities. But I’m not sure he could so easily equate what had happened in the camps, in Neuengamme, with enmity induced by control over an enemy. He and his fellow British guards hadn’t worked the interns to death, hadn’t set dogs on them, hadn’t overseen experiments to see how TB developed in healthy children. They may have been brutal. There was evidence to show there were sadists in the British Army, men who would take the opportunity to let base desires loose. But that’s not the same as signing up to a whole culture and regime designed on one premise: the dehumanisation and destruction of anyone considered an ‘undesirable’, a Jew, a political opponent, a foreigner, an Untermensch. It was different, wasn’t it?

The press had sought drama at Nuremberg too. That was their business: seeking entertainment amongst a decidedly unentertaining process. A slow accumulation of evidence had drained the novelty from proceedings by February 1946, three months into the trial. The Daily Mail reflected: ‘Time marches backwards in the court-room at Nuremberg. Outside the world steps into the future, but here day after day, the past is unrolled … Already it begins to seem remote as it plays about the half-forgotten men in the dock … The atmosphere is at all times tense – the scene theatrical, with its lights, flags, white-helmeted American guards, earphones, and glass-caged interpreters.’7 They waited on the next act with impatience.

On 13 March, as the Neuengamme trial was about to get underway, their curiosity was temporarily reignited. Hermann Goering, the man who’d asserted moral command over the defendants in the dock, who’d imposed his personality on proceedings, taking upon himself the mantle of senior Nazi in the absence of Hitler and Himmler, was called into the witness box. If anything marked the fairness of the trial, of all the trials operated by the British and Americans, it was this ritual opportunity for defendants to justify themselves. Goering grasped the chance with clear delight. He must have known that his time on earth was seeping away, but his ego wouldn’t allow him to go quietly.

Over the next few days, Goering took the stand and gave fulsome answers to questions placed by his counsel. It was an exercise in self-aggrandisement. ‘Bombastic’, ‘unrepentant’ and an enduring loyalty to Hitler were the initial impressions of his performance. His ‘last long speech to the world’ would confirm the character of a German patriot who would do anything that was necessary to strengthen the state. The suppression of opposition and the founding of concentration camps were all essential to solidify power in the Führer’s hands. The end of a steel-strong Germany justified the means, the violence, the wars. When quizzed by his attorney about ‘the Jews’, Goering continued with his sweeping validation. ‘There were many Jews who did not show the necessary restraint,’ he said. They had too much power, too much influence, they opposed National Socialism. He argued if ‘many a hard word which was said by us against Jews and Jewry were to be brought up, I should still be in a position to produce magazines, books, newspapers, and speeches in which the expressions and insults coming from the other side were far in excess’. The Nuremberg Laws were to ‘separate the races’, reduce the power and influence of Jews in public life, he said, ‘until a controlled emigration … should solve this problem’.8 Otherwise, Goering claimed, ‘the Jews on the whole remained unmolested in their economic positions’. ‘The extraordinary intensification which set in later’, as he described the mass extermination, was, he said, a result of one ‘radical group’ in the Nazi movement ‘for whom the Jewish question was more significantly in the foreground’. He denied that the wars of aggression were linked to the destruction of the Jewish race. He denied that extermination had been planned in advance.

Despite this flit across the inhumanity of Nazi rule, Telford Taylor, one of the senior American prosecutors, admitted years later that Goering’s performance was ‘lucid and impressive’.9 The Daily Mail agreed, saying he’d ‘almost talked himself back into his old boisterous and defiant tone’. He ‘not only had the floor of the War Crimes court all day but held his former colleagues in the dock in raptures of admiration as he boasted of his work in building up Nazi power’.10 The Times said he ‘was by no means without dignity and he spoke with the courage of his convictions’.11 He was ‘making the most remarkable speech of his career. His audience is the world and there is an astute calculation behind every word he utters.’12 He was ‘disarmingly frank’, the paper’s correspondent admitted. It was as though all had swooned before the celebrity that Goering had become. It was as though the ‘excesses’ against the Jews, as it was being termed by some of the defendants and their supporters, were an unfortunate and dismissible consequence of an otherwise pure intent and plan of action. Power was Goering’s cause: power for the Führer and power for Germany. That was the almost statesmanlike figure he tried to present. And for many he succeeded. It didn’t make him any less culpable, but it did provide a political glaze that commanded grudging admiration.

Such was the effect of the trial: it provided a platform for the defendants to rationalise everything done by Nazi Germany. Cross-examination, the moment in every Anglo-American trial when the prosecution has the opportunity to cut through the shield constructed by the defence, was the only way of returning the mood to outrage and condemnation. But it takes skill.

Justice Jackson was the man who took responsibility for questioning Goering. It was natural that he who’d brought the Nuremberg Tribunal into being should adopt the task. Someone had to assume the burden. But he took it as a personal mission, one not to be widely shared beforehand with the whole prosecution team. It was his moment. He began uneasily.

‘You are perhaps aware that you are the only living man who can expound to us the true purposes of the Nazi Party and the inner workings of its leadership?’

It was an exercise in mock deference. Observers tried to understand later the reasons for asking that first question. Jackson apparently wrote that he sought to flatter Goering, to draw him into a puffed-up stature so that he would confess to all crimes in a grand show of hubris.13 Perhaps the complimentary nature of press reports on Goering’s performance had irritated Jackson. Perhaps he’d wanted to humiliate the defendant, to show he was despised, a mere man who represented nothing but a corrupt and evil regime. If so, the plan failed. Sir David Maxwell Fyfe wrote to his wife about Jackson’s performance: ‘The oddity about his attempts so far is that they have no form and no follow-up.’14

Reading the transcript, you can see the meandering nature of the questioning. Nothing pierced Goering’s shell. Jackson achieved little more than a repetition by Goering of his defence. The complete lack of impact caused Jackson intense irritation. Goering’s ability to expound at length in reply to every question brought Jackson to the point of breakdown, it seemed. Angrily, he attempted to persuade the tribunal to order Goering to answer ‘Yes or no’ to questions put. He said the trial appeared to be getting ‘out of hand’. It was a remarkable and ineffective outburst that the panel of judges dismissed.

But the impression Jackson gave was accurate. The trial wasn’t achieving the ‘justice’ that the Allies had sought. It was there to be hijacked as all trials of this nature can be. Perhaps more disturbing than Jackson’s inability to crack Goering, though, was his prioritisation. Not once on that first day of cross-examination did Jackson mention the Jews and their extermination. Not once on the second day. It was only well into the third day that Jackson finally brought Goering to address the question. Why he hadn’t started with that subject I couldn’t tell. But even when he did, it was a laboured affair, drawing out from Goering nothing more than he’d already admitted. Maybe Jackson knew that it would be futile, that Goering would plead ignorance, reinforcing the impression that a handful of ‘radicals’ in the SS and under Himmler, as Goering had called them, had taken it upon themselves to kill the Jews of Europe.

Other prosecutors were given the chance to continue the cross-examination once Jackson had finished. Maxwell Fyfe was first and he immediately turned to the killing of the Great Escape officers, the fifty men who’d been executed after their recapture from the Stalag Luft III mass POW breakout. Though undoubtedly a matter of great public notice in Britain, the killing was hardly representative of the Nazi spectrum of atrocity. The benefit of Maxwell Fyfe’s initial questioning, though, lay in his style, not its content. By detailed and pointed examination he made Goering look evasive. When finally Maxwell Fyfe turned to the extermination of the Jews, the defendant was unsettled. But the shield of ignorance that Goering had constructed remained. Maxwell Fyfe reflected on the proven millions killed in the concentration camps and asked, ‘Are you telling this tribunal that a Minister with your power in the Reich could remain ignorant that that was going on?’ Goering said it had been kept secret from him. And from Hitler too, he added.

Maxwell Fyfe said, ‘I am asking about the murder of four or five million people. Are you suggesting that nobody in power in Germany, except Himmler and perhaps Kaltenbrunner, knew about that?’

‘I am still of the opinion that the Führer did not know about these figures.’

‘You did not know to what degree, but you knew there was a policy that aimed at the extermination of the Jews?’

‘No, a policy of emigration, not liquidation of the Jews. I knew only that there had been isolated cases of such perpetrations.’

That admission of awareness, even of ‘isolated cases’, was enough for Maxwell Fyfe. It was the most that he or any attorney was able to extract from Goering.

The British press warmed to the personal nature of the encounter. The Daily Mail reported, ‘The great battle of wits between Hermann Goering and the man he fears most in his trial here, Sir David Maxwell Fyfe, deputy British prosecutor, wound up today with the former Reichsmarshal baffled and beaten.’15 ‘Goering Hard Pressed by British Prosecutor’, the Times headline read.16 Even then, national pride had more influence on perceptions of the trial than the search for accountability.

If the high political justification for what were euphemistically called ‘excesses’ regarding the Jews and all other victims was acknowledged, if not accepted, by Goering in Nuremberg, how could those directly engaged in its delivery excuse their part?

At the Curiohaus, the Neuengamme camp commandant, Max Pauly, entered the witness box as the first of the accused to put his defence. Just as with Goering, he was given hours to answer the questions of his counsel. He explained how he’d joined the SS, wanted to be part of an SS fighting unit in the war, but had instead been posted to the Danzig Security Police. From there, between 1939 and 1942, he’d assumed command of Stutthof KZ, built some 40 kilometres east of the city. Initially, the camp imprisoned Jews and Poles from Danzig and the surrounding country, but in 1942 it was incorporated fully into the KZ system. It was then that Pauly had been transferred to Neuengamme KZ as commandant.

Unlike Goering, Pauly played down his importance, his knowledge of crimes, denying the claims made by all the witnesses who’d appeared so far. He passed on responsibility to anyone else he could: his SS colleagues in the camp, his superiors in the Hamburg district and predictably all those powerful names in Berlin. It was another act of multiple deflection: Thumann was the officer whose cruelty defined the conditions in the camp, Pauly claimed; Dr Trzebinski was solely responsible for the killing of the children at Bullenhuser Damm; Bassewitz-Behr had given the order to kill the inmates from Fuhlsbüttel prison as the Allies advanced; and General Oswald Pohl, the man responsible for the organisation of all concentration camps and whom the British War Crimes Investigation Unit would soon apprehend, was the one who’d instructed KZ commandants at a conference in Berlin that all prisoners should be exterminated by whatever means if the Allies invaded. And orders had to be obeyed, Pauly said. It was an extension of Goering’s power hierarchy, measured by total obedience.

Major Stewart’s cross-examination was his first in the case. As they were finding at Nuremberg, these moments defined the success of the trial, at least in so far as an audience might perceive the performance. Not that it could matter much in terms of the result, the simple announcement of guilt or innocence. But a poor interrogation by the prosecutor and the whole procedure would look shabby. It might encourage the German population to think this was a sham. They might think this was just an act of theatre and condemn the findings of the court. And where would that leave the project of retribution through proper and fair legal process?

How to start well, then? Stewart had been one of the team at the Belsen trial. He would have remembered his colleague Colonel Backhouse and his opening question to Josef Kramer. His was very nearly the same and prompted an odd exchange.

‘Pauly,’ Stewart said, ‘I saw you swear on the Bible yesterday much to my surprise. How is that? Do you believe in it?’

‘Yes.’

‘Am I right in saying that all members of the SS, officers or other ranks, had to leave their church on entering the SS?’

‘I joined the SS in 1931 and at that time there was no such order.’ But later, when promoted, officers were expected to leave the Church, he said. This happened for him in 1934 or 1935.

‘Why then do you swear on the Bible?’

‘I have nothing to do with the SS any more and the SS cannot do anything about it if I want to return to the church.’

The claim was almost redemptive. A sinner repenting. And a sinner who’d never renounced his beliefs but had only hidden them. Pauly explained he’d been forced into the SS, first because he needed money and then by the dictates of party leaders. He sketched the image of a young man (he was thirty-two in 1939) who’d been compelled to do what he was told. But underneath was a moral core that had now been released.

Stewart’s gambit was threatened. He had to prick this balloon of inner innocence. This was a member of a select band of maleficent figures, the KZ commandants. He couldn’t be allowed any redemption, not here, not in the name of God. That would challenge the divine nature of justice that this trial and all the others had assumed. Stewart had to demonstrate that Pauly wanted to work in the camps, that he’d chosen to do so or at least had taken the role seriously.

Just as Jackson had been condemned for his opening question at Nuremberg, Stewart could have been equally criticised. Reference to the Church and Pauly’s supposed refound religious conviction was an interesting way of provoking the ex-commandant. That Pauly had a defence strategy had been emphasised in the examination by his lawyer. But Stewart gave him the opportunity to repeat his claims that he was a victim himself, he’d had to join the SS, he’d had to obey their orders and he couldn’t serve both God and the organisation at the same time, though beneath the black uniform he’d been a believer who’d resisted where and when he could, following commands as any underling or junior officer had been obliged to do. It may have been an unconvincing story, given the recent revelations about the absolute power over life that all KZ commandants possessed. Pauly nonetheless maintained consistently that he’d been ignorant of the whole system, that his time in Stutthof hadn’t prepared him for KZ service, that he’d been aware illegal killings and ill-treatment had occurred in concentration camps, but he’d been determined not to follow suit.

Pauly was asked why he hadn’t served with the Waffen-SS and fought in France, why instead he was placed in charge of a camp in Stutthof?

Those were my orders, Pauly said. He’d asked to fight at the front but had been put in command of the civilian internment camp near Danzig instead. Stutthof had been changed into a concentration camp only later, in 1942.

What was the difference, Stewart asked, between Stutthof the civilian internment camp which Pauly commanded from 1939 to 1942 and Stutthof the KZ from 1942 onwards?

The ‘inmates were allowed to keep their own clothes’, Pauly said.

Was that all?

Pauly avoided answering. He became glib. ‘They were behind barbed wire just in the same way.’

But their treatment?

‘The laws and regulations in an internment camp were different. I certainly tried in Stutthof and Neuengamme to treat the prisoners properly.’

Turning to his term as Neuengamme commandant, Pauly said, yes, the Reichsführer Himmler gave authority to order capital punishment, but he hadn’t made use of it. It only applied to Russians anyway, he said (as if that would be acceptable to everyone in the courtroom), and even then he’d only carried out ‘executions when they were ordered by higher authority’.

As camp commandant could he order other punishments?

‘Reprimands, arrest, withdrawal of a meal and withdrawal of food,’ Pauly said.

What did that last punishment entail?

Missing a Sunday midday meal for three consecutive weeks, Pauly claimed rather too innocently. He portrayed a regime where punishment was infrequent, light, without violence. Only if he received a direct order from Berlin could he authorise beatings, he said.

Stewart’s incredulity was met with the same response: Pauly had seen nothing and read no order which could prove he was lying.

Ridicule was Stewart’s next tactic. How could Pauly argue that he was in command and yet had no idea what was happening in the bunker, in the brickworks, in the punishment companies, to which all of the witnesses had testified and the other defendants had confirmed in their statements?

Max Pauly stood fast.

Then Stewart quizzed him about his knowledge of other camps, other camp commandants. Pauly admitted he’d met Kramer, commandant of Belsen and Auschwitz, and Rudolf Höss, commandant of Auschwitz too. They would gather in Berlin when summoned to discuss concentration camp policy. None of them had told him about their camps, he said, although he’d heard about gassings. If he’d been required to transfer sick patients to these other camps, it was in order to have them cured, Pauly said.

‘Do you really want to tell this court that after having conferences with all these camp commandants including Kramer and Höss you really believe that people went to Belsen and Lublin to be cured?’

Max Pauly portrayed himself as wandering amidst a host of cruel and despicable men without noticing. Reading the exchange with Stewart, it occurred to me that Pauly was becoming a metaphor for the whole German nation.

The crimes Stewart mentioned then became more specific. Did he remember the execution of the men and women from Fuhlsbüttel in April 1945?

Yes.

Who ordered the killings?

The higher SS and police commander in Hamburg.

Did Pauly give Thumann the order to carry this out?

Yes.

And when Thumann killed some of the Fuhlsbüttel people with hand grenades, what did he do?

Reprimanded Thumann. Severely.

And the hospital? Did he visit that place?

Yes.

Did he know about Willi Bahr and the injections he’d used to kill inmates?

He knew nothing about them.

What about the orders from Goebbels and Himmler approving the ‘extermination through work’ policy to be applied in the camps: what did he think of them?

He knew nothing about them either.

The cross-examination ended weakly. Faced by a wall of innocence and denial, Stewart had little to exploit. He had to rely on disbelief that Pauly could have been so blind to the deaths and brutality that the witnesses had said defined this KZ and the whole concentration camp system. Pauly was one of an elite band, men who were paraded now as the embodiment of Nazi ideology put into practice. If you were a camp commandant you had to be privy to the whole structure and policy of imprisonment and extermination. Every major KZ operated within this web. Prisoners and guards, and commandants too, moved between the main centres continually. The most senior SS officers were brought to Berlin to attend regular meetings about the organisation of the system. No one in such a position as Pauly could possibly be so ignorant of the wholesale killing that the camps oversaw.

The ever fair Judge Advocate Stirling wasn’t satisfied. He was entitled to ask his own questions if he thought there were unresolved matters, often a sign that the prosecution hadn’t been thorough. Stirling asked where Pauly had lived whilst serving as commandant. Inside the camp, Pauly said, ten minutes’ walk to the main gate in that little white house behind one of the brick barracks. His children had joined him there from Danzig.

The mention of children prompted Stirling to talk about the Jewish girls and boys who had been experimented on and killed in Bullenhuser Damm. Pauly knew about them and had followed orders unwillingly. He’d already admitted that. Orders couldn’t be countermanded by him, however unpleasant. He accepted too that the two French professors, Florence and Quenouille, were sent with the children to be executed with them.

Stirling asked him about the death rate in the camp. Pauly blamed the high number of sick prisoners transferred to Neuengamme from other places. They arrived in such a state, he said, that there was little anyone could do, though they tried their very best, he assured the court.

He presented himself as a professional, a soldier who had done his duty and had cared for his charges as much as he was allowed. There was no contrition and no acceptance of guilt, responsibility, anything that connected him morally with those whose killings and deaths and tortures he’d overseen.

Pauly’s defence shifted the gaze of those in the Curiohaus proceedings onto the general structures of the Nazi regime. That was his aim: to pass blame to those further up the hierarchy. Even though a camp commandant, Pauly argued that he was a lowly figure in the SS, preconditioned, as all military men were, to obey all orders. He was nothing more than a common foot soldier, nothing more than a functionary in the KZ system, who’d served his time and followed commands.

For a moment the proceedings in Hamburg and a few hundred miles away in the tribunal at Nuremberg became intertwined. On 15 April 1946, a week or so after Pauly had given his evidence, Rudolf Höss was called to testify in Nuremberg. He epitomised the dark soul of the Nazi era. As commandant of Auschwitz between 1940 and 1943 he’d administered part of the programme to exterminate the Jews of Europe and was at the top of the list of wanted war criminals. His arrest in March 1946 by No. 1 War Crimes Investigation Unit, Captain Hanns Alexander leading the operation, was a triumph. The confession that followed, with Höss revealing the innermost secrets of the ‘Final Solution’ and his role within it, couldn’t have been better timed for the Allies in Nuremberg in their determination to prove that extermination, not resettlement, was the Nazi plan. The trouble was the prosecution had already rested its case by the time Höss had been captured.

To make the most of his confession, the Allied prosecutors offered Höss to the accused. Kaltenbrunner was about to present his defence and Dr Kauffmann, his attorney, needed a witness to support his argument that Kaltenbrunner had had no responsibility for the death camps or the extermination of the Jews. After being allowed by the Americans to interview Höss, Kauffmann believed that the Auschwitz commandant would support this contention. He called Höss as a defence witness and questioned him. The exchange that began Kauffmann’s examination was terse, matter-of-fact.

‘From 1940 to 1943, you were the Commander of the camp at Auschwitz. Is that true?’

‘Yes.’

‘And during that time, hundreds of thousands of human beings were sent to their death there. Is that correct?’

‘Yes.’

‘Is it true that you, yourself, have made no exact notes regarding the figures of the number of those victims because you were forbidden to make them?’

‘Yes, that is correct.’

‘Is it furthermore correct that exclusively one man by the name of Eichmann had notes about this, the man who had the task of organizing and assembling these people?’

‘Yes.’

‘Is it furthermore true that Eichmann stated to you that in Auschwitz a total sum of more than 2 million Jews had been destroyed?’

‘Yes.’

‘Men, women, and children?’

‘Yes.’

Like Pauly, Höss had risen through the ranks of the SS concentration camp hierarchy. First at Dachau then Sachsenhausen. In May 1940 he’d become commandant of Auschwitz. The following year he’d been called to Berlin by Himmler.

Höss said of this meeting, ‘He told me something to the effect – I do not remember the exact words – that the Führer had given the order for a final solution of the Jewish question. We, the SS, must carry out that order. If it is not carried out now then the Jews will later on destroy the German people. He had chosen Auschwitz on account of its easy access by rail and also because the extensive site offered space for measures ensuring isolation.’

Kauffmann asked, ‘During that conference did Himmler tell you that this planned action had to be treated as a secret Reich matter?’

‘Yes. He stressed that point. He told me that I was not even allowed to say anything about it to my immediate superior Gruppenführer Glücks. This conference concerned the two of us only and I was to observe the strictest secrecy.’

Glücks had been the inspector of concentration camps under Himmler. Asked what ‘secret Reich matter’ meant, Höss said, ‘No one was allowed to speak about these matters with any person and that everyone promised upon his life to keep the utmost secrecy.’

Had he broken that promise?

Yes, he said. He’d told his wife when she’d asked him about rumours she’d heard. The Gauleiter of Upper Silesia had mentioned to her that Jews were being killed in their thousands in Auschwitz and she’d been curious whether it was true. He’d told her the truth, he said. But otherwise he’d divulged the secret to no one else.

What was this truth?

Höss told how his camp, isolated, surrounded by empty countryside, operated.

The Auschwitz camp as such was about 3 kilometers away from the town. About 20,000 acres of the surrounding country had been cleared of all former inhabitants, and the entire area could be entered only by SS men or civilian employees who had special passes. The actual compound called ‘Birkenau’, where later on the extermination camp was constructed, was situated 2 kilometers from the Auschwitz camp. The camp installations themselves, that is to say, the provisional installations used at first were deep in the woods and could from nowhere be detected by the eye. In addition to that, this area had been declared a prohibited area and even members of the SS who did not have a special pass could not enter it. Thus, as far as one could judge, it was impossible for anyone except authorized persons to enter that area.

And what happened there?

During the whole period up until 1944 certain operations were carried out at irregular intervals in the different countries, so that one cannot speak of a continuous flow of incoming transports. It was always a matter of 4 to 6 weeks. During those 4 to 6 weeks two to three trains, containing about 2,000 persons each, arrived daily. These trains were first of all shunted to a siding in the Birkenau region and the locomotives then went back. The guards who had accompanied the transport had to leave the area at once and the persons who had been brought in were taken over by guards belonging to the camp. They were there examined by two SS medical officers as to their fitness for work. The internees capable of work at once marched to Auschwitz or to the camp at Birkenau and those incapable of work were at first taken to the provisional installations, then later to the newly constructed crematoria.

Kauffmann prompted Höss to emphasise the concealment of the process.

Sixty men were always on hand to take the internees not capable of work to these provisional installations and later on to the other ones. This group, consisting of about ten leaders and sub-leaders, as well as doctors and medical personnel, had repeatedly been told, both in writing and verbally, that they were bound to the strictest secrecy as to all that went on in the camps.

Kauffmann asked, ‘And after the arrival of the transports were the victims stripped of everything they had? Did they have to undress completely; did they have to surrender their valuables? Is that true?’

‘Yes.’

‘And then they immediately went to their death?’

‘Yes.’

‘Did these people know what was in store for them?’

‘The majority of them did not, for steps were taken to keep them in doubt about it and suspicion would not arise that they were to go to their death. For instance, all doors and all walls bore inscriptions to the effect that they were going to undergo a delousing operation or take a shower. This was made known in several languages to the internees by other internees who had come in with earlier transports and who were being used as auxiliary crews during the whole action.’

‘And then, you told me the other day, that death by gassing set in within a period of 3 to 15 minutes. Is that correct?’

‘Yes.’

‘You also told me that even before death finally set in, the victims fell into a state of unconsciousness?’

‘Yes. From what I was able to find out myself or from what was told me by medical officers, the time necessary for reaching unconsciousness or death varied according to the temperature and the number of people present in the chambers. Loss of consciousness took place within a few seconds or a few minutes.’

Then a sudden shift from Kauffmann, one which would serve no great purpose for his client; maybe he simply couldn’t listen to the deliberate and prosaic description of industrialised killing without some emotional response. Kauffmann asked, ‘Did you yourself ever feel pity with the victims, thinking of your own family and children?’

‘Yes.’

‘How was it possible for you to carry out these actions in spite of this?’

‘In view of all these doubts which I had, the only one and decisive argument was the strict order and the reason given for it by the Reichsführer Himmler.’

Himmler’s name drew Kauffmann back to the defence of his client.

‘I ask you whether Himmler inspected the camp and convinced himself, too, of the process of annihilation.’

‘Yes. Himmler visited the camp in 1942 and he watched in detail one processing from beginning to end.’

‘Does the same apply to Eichmann?’

‘Eichmann came repeatedly to Auschwitz and was intimately acquainted with the proceedings.’

‘Did the defendant Kaltenbrunner ever inspect the camp?’

‘No.’

‘Did you ever talk with Kaltenbrunner with reference to your task?’

‘No, never.’

I watched the old film of this exchange. One of the judges tapped his pencil, took a sip of water from a beaker in front of him. Officials and lawyers around the courtroom pressed headphones to their ears. As Höss talked of the ‘final solution’ guards stood to attention behind him, stenographers typed away on their machines, and Höss sat small and slightly hunched, delivering his breathless evidence. Everyone looked sombre but none of the faces registered shock. I supposed they’d heard all this before. It had become commonplace, non-revelatory, even bland now in that courtroom.

It wasn’t Dr Kauffmann’s intention to reveal the horror of the Holocaust. His only concern was to prove that his client, Kaltenbrunner, the most senior SS officer before the Major War Criminals trial, second only to Himmler in the SS hierarchy after Heydrich had been killed in Prague, had known nothing about the extermination of the Jews. Whatever else he was accused of, this abomination couldn’t be laid at his door, so the advocate claimed. Höss was supposed to confirm that the mass killing was kept tightly secret, only known by a handful of men, like Himmler and Eichmann and of course the few SS guards who had to carry out the gassing operations.

It was a simplistic representation. If Höss’s wife had heard about the extermination in Auschwitz from sources who hadn’t had the necessary security clearance, then the secret hadn’t been that well kept. And what about all those who hadn’t been killed, the other guards and SS officers, hundreds who came and went? And the same numbers who had undertaken similar extermination procedures in other camps, in Treblinka and Belzec and Majdanek and Sobibór?

Under cross-examination Höss repeated his confession, given to the Allies a few days earlier, that although he’d been required to operate in secrecy, ‘of course the foul and nauseating stench from the continuous burning of bodies permeated the entire area and all of the people living in the surrounding communities knew that exterminations were going on at Auschwitz’.

How likely was it, then, that men like Kaltenbrunner could not have known about the mass killing? How likely was it, when gathered together in Berlin or Oranienburg, as they did through the central KZ Inspectorate, the concentration camp commandants, Max Pauly included, hadn’t heard about, talked about, the mass killing in Auschwitz and the other death camps? How likely was it that when trainloads of Jews passed through the labour camps such as Neuengamme and Bergen-Belsen, to be shipped on to Auschwitz, that no one had understood the reason for their journey?

Further evidence given by Höss made a nonsense of the idea of covert killing on such a scale. He described the way in which Auschwitz worked beyond its role as a killing factory. He’d said in his statement to the American interrogators that 2,500,000 people had been killed by ‘gassing and burning’ and another 500,000 had died from starvation and disease whilst in the camp. This figure, he said, represented 70–80 per cent of the prisoners sent to Auschwitz. The rest were selected for slave labour in the concentration camp industries. Prisoners would come and go through Auschwitz. They would end up in places like Neuengamme for distribution amongst the many sub-camps for agricultural and industrial work, all for the war. They would take with them their knowledge of the slaughtering. Even if they only talked of the smell, rumours would spread. How secret then was the extermination?

But if Max Pauly somehow managed to keep his ears closed about the killing, could he really maintain his innocence over the ill-treatment within his own camp? Höss said of Auschwitz,

The internees were treated severely, but methodical beatings or ill-treatments were out of the question. The Reichsführer gave frequent orders that every SS man who laid violent hands on an internee would be punished; and several times SS men who did ill-treat internees were punished …

If any ill-treatment of prisoners by guards occurred – I myself have never observed any – then this was possible only to a very small degree since all officers in charge of the camps took care that as few SS men as possible had direct contact with the inmates …

In the course of the years the guard personnel had deteriorated to such an extent that the standards formerly demanded could no longer be maintained. We had thousands of guards who could hardly speak German, who came from all lands as volunteers and joined these units, or we had older men, between 50 and 60, who lacked all interest in their work, so that a camp commander had to watch constantly that these men fulfilled even the lowest requirements of their duties. It is obvious that there were elements among them who would ill-treat internees, but this ill-treatment was never tolerated …

Of course a great deal of ill-treatment occurred which could not be avoided because at night there were hardly any members of the SS in the camps. Only in specific cases were SS men allowed to enter the camp, so that the internees were more or less exposed to these Kapos.

Pauly might have nodded at Höss’s claims as support for his position, but even for him the evidence was self-defeating: though Höss said ill-treatment hadn’t been tolerated, he and everyone else had known that it happened. Passing blame to the Kapos couldn’t dislodge the duty of care which Höss said was supposed to permeate the camps. The same had to apply to Pauly.

Then there was the matter of the final year in the story of the KZs. Höss repeated much that the defence had said on Pauly’s behalf, and had been raised in the Belsen trial six months earlier. He marked 1944 as the period when the pure order of the concentration camps, as he characterised it, broke down. He said,

When the war started and when mass deliveries of political internees arrived, and, later on, when prisoners who were members of the resistance movements arrived from the occupied territories, the construction of buildings and the extensions of the camps could no longer keep pace with the number of incoming internees. During the first years of the war this problem could still be overcome by improvising measures.

That all changed when materials for construction stopped arriving, and rations for internees were cut. The prisoners ‘no longer had the staying power to resist the now gradually growing epidemics’.

The main reason why the prisoners were in such bad condition towards the end of the war, why so many thousands of them were found sick and emaciated in the camps, was that every internee had to be employed in the armament industry to the extreme limit of his forces. The Reichsführer constantly and on every occasion kept this goal before our eyes … Every commander was told to make every effort to achieve this. The aim was not to have as many dead as possible or to destroy as many internees as possible; the Reichsführer was constantly concerned with being able to engage all forces available in the armament industry.

As the war had drawn to a close, Höss said,

The number of the sick became immense. There were next to no medical supplies; epidemics raged everywhere. Internees who were capable of work were used over and over again. By order of the Reichsführer, even half-sick people had to be used wherever possible in industry. As a result every bit of space in the concentration camps which could possibly be used for lodging was overcrowded with sick and dying prisoners.

It was all unconvincing. Though individual commandants like Pauly and Josef Kramer may have faced an impossible task, inundated with increasing numbers of inmates with whom they could not cope, they had been prominent in the maintenance of the system. They had been instrumental in its operation. Höss might have confirmed the unforgiving and desperate position towards the end of the war, but the existence of the system, constructed over a decade and more, made ill-treatment and death inevitable. That was the culpability that could not be shaken off across the spectrum of ranks.

A different form of defendant took the stand after Pauly had finished presenting his defence. Anton Thumann was a man who had no part to play in the grand decisions which opened and closed the KZs. He’d forged a career in the camps, working his way up the hierarchy, demonstrating his willingness to use whatever violent measure he felt like employing. It was a skill valued by those senior to him. No one could ever doubt, so it would seem, Thumann’s commitment to the underlying purpose of the camps.

When Thumann came to give evidence, though, he denied the portrait the prosecution had crafted. Commandant Max Pauly was the evil influence, he claimed. Despite being Pauly’s deputy, Thumann said he had no power to do anything other than follow the commandant’s orders. Everyone had feared Pauly, Thumann said. ‘When the commandant came to the camp my predecessor would leave by the window.’

Pauly had two characters, according to Thumann, ‘One a brutal one and the other the one he presented here in court.’ But his brutality was mostly directed at the SS leaders, not the prisoners. It consisted of ‘words’. He ‘dressed everyone down’.

Thumann was not a particularly clever man. He demonstrated that quickly enough. Asked by his attorney, Dr Koenig, whether he’d signed a document declaring that he would not beat prisoners, he said ‘yes’ but then confessed that he hadn’t obeyed it. ‘Because without being able to punish them myself on the spot I would not have been able to keep the required order and discipline.’ He admitted to hitting prisoners in the face, of beating with a stick ‘five to twenty-five strokes’, of owning a ‘wolf dog’ which he assured the court he’d never turned on anyone, though it would dive at a prisoner should Thumann strike him. He presented himself as a slave to the commandant and the hierarchy stretching above Pauly to the upper ranks of the SS. And he said he hated the regime under his superior. He had even applied for a transfer to the front. His commandant’s approach hadn’t been what he joined the SS for: ‘In peace time the idea was to re-educate prisoners, and in war time they were to be included in the war effort.’ He did not believe a policy of extermination through work had been created. Yes, he’d conducted executions, but every Lagerführer was required to do that: orders came from the Reichsführer-SS. Thumann had no choice but to obey. And that was what he did: carry out those orders. ‘If the orders said “To be hanged” then we hanged them; if the orders said “To be shot” then we shot them.’

Reading Thumann’s testimony made me think the defence of unwilling obedience was self-defeating. To be credible he had to admit that he’d carried out the most atrocious of crimes. He had to demonstrate the total corruption of his autonomy by acknowledging the killings and beatings as part of a daily ordering of his life. It had to extend to the execution of the children in Bullenhuser Damm. And Thumann indeed confirmed, ‘I can only say that I had given the order to Rapportführer Dreimann for Speck and Wiehagen to arrange the convoy to transport these children to that place.’

But it was his account of the killing of the detachment of prisoners from Fuhlsbüttel on 23 and 24 April 1945 that marked Thumann. He said he’d been ordered to accept the convoy from the Hamburg prison and execute them. It was an ‘untimely’ duty. He was overworked. ‘On that particular day 4,500 Jews were evacuated,’ he said, as though describing the despatch of a consignment of boxes. Thumann accepted the fifty-eight men and thirteen women from the Gestapo’s prison at Fuhlsbüttel, separated them, then fixed the execution for the following night. Then between 9 p.m. and 9.30 p.m. he’d stood at the entrance of the execution bunker and watched by lamplight as first the women were brought in their underwear, stood on chairs and hanged. The men were next. Six were executed in the same fashion without any problems. But when he went to the cells to collect the next batch, the inmates attacked him with a wooden bar from one of the cell beds. Thumann remembered it as though he were in the middle of a furious battle at the front.

I was hardly conscious, I could just about stand. I was quite defenceless. One of the prisoners came out of the cell and attacked Blockführer Brems. Whether I shut the door or somebody else did I can’t remember. The prisoner who had attacked Brems and given him a stab in the upper region of the chest was then shot by Brems … The other prisoners then barricaded the door.

Thumann called for a ladder to look through the high cell window. The prisoners couldn’t be seen. They’d set themselves back in the corners. When he put his hand in and tried to shoot them, his hand was hit and the pistol fell into the cell. Thumann called for grenades. The prisoners fired several shots. A grenade was thrown in. The explosion demolished the wall between two cells. All but one of the prisoners were buried in the debris. Thumann grabbed a machine pistol, stuck it through the food hatch and fired. ‘I gave every one of the prisoners a short burst as I was not quite sure whether they were dead or not.’

‘Did you consider yourself justified in resorting to these extreme measures?’ Thumann’s lawyer asked.

‘I was convinced of it in order to protect my subordinates.’

His conviction lacked substance: ‘After I had finished off the male prisoners with my machine pistol I left the bunker and a short while afterwards I heard a woman scream. I went to the door and saw a woman inside in a crouched position by the door and she was yelling horribly. I was of the impression that she was injured and I shot her.’

Then he retired for the night.

The next evening, he said, he’d dealt with the rest. ‘I had the prisoners undressed and I shot them myself.’

Why?

‘I took the moral responsibility from the shoulders of my subordinate officers on to my own.’

There was little to add. Only that on 2 May 1945 he’d heard the firing from the front and he’d left Neuengamme. He and the commandant had travelled towards Plön, hoping to catch up with the guards and prisoners from the camp. On the way they’d heard Neustadt had been taken and so headed for Wesselburen, where the commandant’s in-laws lived. Then they’d travelled to Flensburg, where Thumann was spotted by some former inmates.

Thumann’s life story was almost over.

I was fascinated by Thumann. I’m not entirely sure why. Perhaps it was his photograph, his face. He looked not just ordinary, but kindly. The slight upward curve at the corners of his mouth suggested a humorous man, someone wanting to break into laughter. We set so much store on facial features, judge quickly on appearances. And a glance at Thumann made me feel pity for him and his predicament. I wondered if I’d have warmed to him if I’d met him. But photographs are poor means by which to assess a person. In the flesh he might well have exuded a completely different personality. Maybe his cruelty and mercilessness would have shown in his eyes, his demeanour. How could I possibly tell?

Did it matter anyway, whether he was a pleasant man or an evil one? His prosecution wasn’t based on his character, nor was his defence. He’d been following orders, he said by way of excuse. But Nuremberg negated such a plea, its fourth principle saying: ‘The fact that a person acted pursuant to order of his Government or of a superior does not relieve him from responsibility under international law, provided a moral choice was in fact possible to him.’

Had Thumann a moral choice? He’d admitted as much in carrying out the executions of the Fuhlsbüttel prisoners rather than leave them to his subordinates. Whether or not he enjoyed the killing mattered little, other than perhaps when it came to sentencing him for his crimes. A sadist couldn’t have expected mercy. But can you really tell the difference between a sadist and a man programmed to kill, who takes a weapon and carries out an order with efficiency and, perhaps more importantly, without apparent disgust at his own actions?

Not more than a couple of years ago, whilst I was in the middle of writing this book, the question of moral choice for a soldier became a public concern in Britain. Marine ‘A’, as he was identified during proceedings, was charged with murdering a Taliban fighter in Afghanistan in 2011. The enemy combatant had been wounded and lay helpless on the ground. He’d been dragged to the side of a field where Marine ‘A’ had shot him in the chest, saying, ‘Shuffle off this mortal coil, you cunt. It’s nothing you wouldn’t do to us.’ The killing and the words had been caught on the helmet camera of another soldier and Marine ‘A’ had been charged, convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment.

On the face of the reported evidence, which was the limit of my knowledge about the case, the marine had to be guilty. He’d broken one of the fundamental rules of legalised warfare: you don’t kill anyone who can’t defend themselves. If they’re hors de combat then shooting them is a crime. Simple. That’s the law. And Marine ‘A’ had a moral choice. He wasn’t compelled or ordered to shoot the unarmed, wounded man. Unless you believe that the stress of intense battle and the training in violence inherent in any soldier’s preparation took away the marine’s free will. Then the question of moral choice becomes a little more complicated. What choice do you have when compulsion, a psychological issue, is the product of insidious, subliminal influences? Don’t we give credence to the impact of many factors on the ‘free will’ of individuals? Don’t we accept that in some situations, people act according to the dictates of education, training, mental indoctrination, conditioning, institutionalisation?

Sometimes. Those who commit a clear-cut crime may be judged sympathetically, perhaps even absolved altogether. But the occasions when this is allowed are tightly constrained. Our sympathies depend on the capacity of our imagination to think, ‘Maybe I would have committed the same awful deed if I’d experienced those pressures.’ I might still have to accept punishment, as the wrong remains a wrong, though the moral responsibility might have been tempered.