37.

“I Found Myself Impaled on the Axis Mundi”

BARBARA MYERHOFF

( 1974 )

Barbara Myerhoff studied anthropology at the University of California Los Angeles at the same time as Carlos Castaneda. She went on to become the first anthropologist, with Peter Furst, to accompany the Huichol Indians of Mexico on their pilgrimage across the desert during which they hunt for the hallucinogenic peyote cactus. To prepare for this, Myerhoff ate peyote under the supervision of Huichol shaman Ramón Medina Silva. The following is an account of her experience.

“Ramón,” I asked, “What would I see if I were to eat peyote?” “Do you want to?” he replied unexpectedly. “Yes, very much.” “Then come tomorrow, very early and eat nothing tonight or tomorrow. Only drink a little warm water when you get up in the morning.” The Huichols, unlike the neighboring Cora and Tarahumara Indians, have no fear of peyote. Ordinary men, women, and children take it frequently with no sickness or frightening visions, as long as the peyote they use has been gathered properly during an authentic peyote hunt. Ramón assured me that the experience in store for me would be beautiful and important and I trusted him and his knowledge completely by this time.

The next morning he led me into the little hut and began feeding me the small green “buttons” or segments, one after another, perhaps a dozen or more in all. He cut each segment away from the large piece he held and prepared it in no way that I could see, for the small pieces I was given retained all their skin, dirt, and root. The tiny fuzzy white-gray hairs that top each segment were intact and only the small button-most portion of the root had been pared off. The buttons were very chewy and tough, and unspeakably bitter-sour. My mouth flooded with saliva and shriveled from the revolting flavor, but no nausea came. “Chew well,” Ramón urged me. “It is good, like a tortilla, isn’t it?” But I was no longer able to answer.

After giving me what he felt was the proper dosage, Ramón indicated that he was going to wait outside and directed me to lie down quietly and close my eyes. For a long time I heard him singing and playing his little violin and then there were new sounds of comings and goings and soft laughter. “They’ve all come to stare at me and laugh,” I thought. “Come on,” I imagined them saying to each other. “Peek inside, we’ve got a gringa in there and we’ve given her a weed. You can get those anthropologists to eat anything if you tell them it’s sacred. She thinks she’s going to have a vision!”

But these thoughts were more amusing than ominous, for I really did not believe that Ramón would deceive me. After an inestimable period of time I began to be aware of a growing euphoria; I was flooded with feelings of goodwill. With great delight I began to notice sounds, especially the noises of the trucks passing on the highway outside. Although I discovered that I couldn’t move, I was able to remain calm when it occurred to me that this was of no consequence because there was no other place that I wanted to be. My body assumed the rhythm of the passing trucks, gently wafting up and down like a scarf in a breeze. Time and space evaporated as I floated about in the darkness and vague images began to develop. I realized that I could keep track of what was happening to me and remember it if I thought of it not as a movielike flow of time but as a discrete series of events like beads on a string. I could go from one to the next and though the first was perhaps out of sight, it had not disappeared as do events in ordinary chronology. It was like a carnival with booths spread about to which I could always return to regain an experience, a Steppenwolflike magical theater. The problem of retaining my experience was thus solved. There remained only the hazard of getting lost. But Ramón had prepared me for this; though he was outside the hut, I felt that as my guide and craftsman, he had left me a thread by means of which I could trace and retrace my peregrinations through the labyrinth and thus return safely from any far-flung destination. Assured by this notion, I started out.

The first “booth” found me impaled on an enormous tree with its roots buried far below the earth and its branches rising beyond sight, toward the sky. This was the Tree of Life, the axis mundi or world pole which penetrates the layers of the cosmos, connecting earth with underworld and heaven, on which shamans ascend in their magical flights. The image was exactly the same as a Mayan glyph which I was to come across for the first time several years after this vision occurred.

In the next sequence, I beheld a tiny speck of brilliant red flitting about a forest darkness. The speck grew as it neared. It was a vibrant bird who, with an insouciant flicker, landed on a rock. It was Ramón as psychopomp, as Papageno—half-man, magic bird, bubbling with excitement. He led me to the next episode which presented an oracular, gnomelike creature of macabre viscosity. I asked the question, the one that had not been out of my mind for months, “What do myths mean?” He offered his reply in mucid tones, melting with a deadly portentousness that mocked my seriousness. “The myths signify—nothing. They mean themselves.” Of course! They were themselves, nothing equivalent, nothing translated, nothing taken from another more familiar place to distort them. They had to be accepted in their own terms. I was embarrassed that as an aspirant anthropologist I had to be told this basic axiom of the discipline, but I was amused and relieved for in a vague way I had known it all along.

My journey ended many booths later, as I sat concentrating on a mythical little animal, aware that the entire experience was drawing to a close. The little fellow and I had entered a yarn painting and he sat precisely in the middle of the composition. I watched him fade and finally disappear into a hole and I made an extra effort to concentrate on him, convinced that a final lesson—a grand conclusion—was about to occur. Just as he vanished, an image flicked into the corner of my vision. In the upper righthand quadrant of the painting, another being had just jumped out of sight. I had missed him and he was the message. There it was! I had lost my lesson by looking for it too directly, with dead-center tight focus, with will and impatience. It was a practice which I knew fatal to understanding anything truly unique. It was my Western rationality, honed by formal study, eager to simplify, clarify, dissect, define, categorize, and analyze. These techniques, exercised prematurely, are antithetical to good ethnographic work and this I was to learn and learn and forget and relearn. The message could emerge anywhere on the canvas; one had to be alert, patient, receptive to whatever might occur, at any moment, in whatever ambiguous, unpredictable form it assumed, reserving interpretation for a later time. In the years to come, the vision was to serve as a mnemonic for this principle and help me keep it in the foreground of my consciousness for all that was ahead.

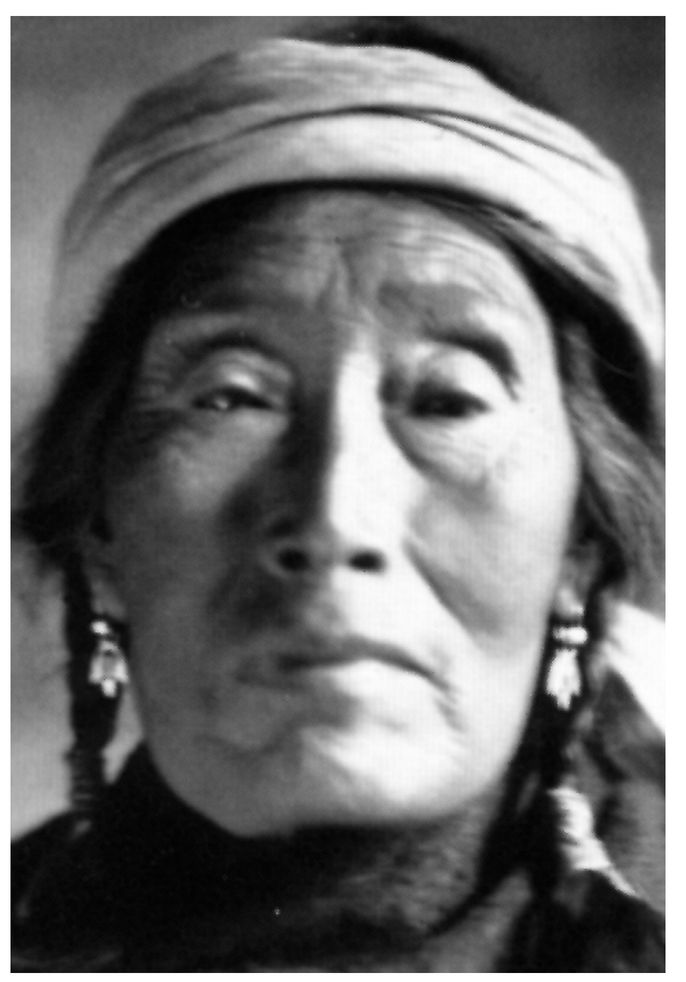

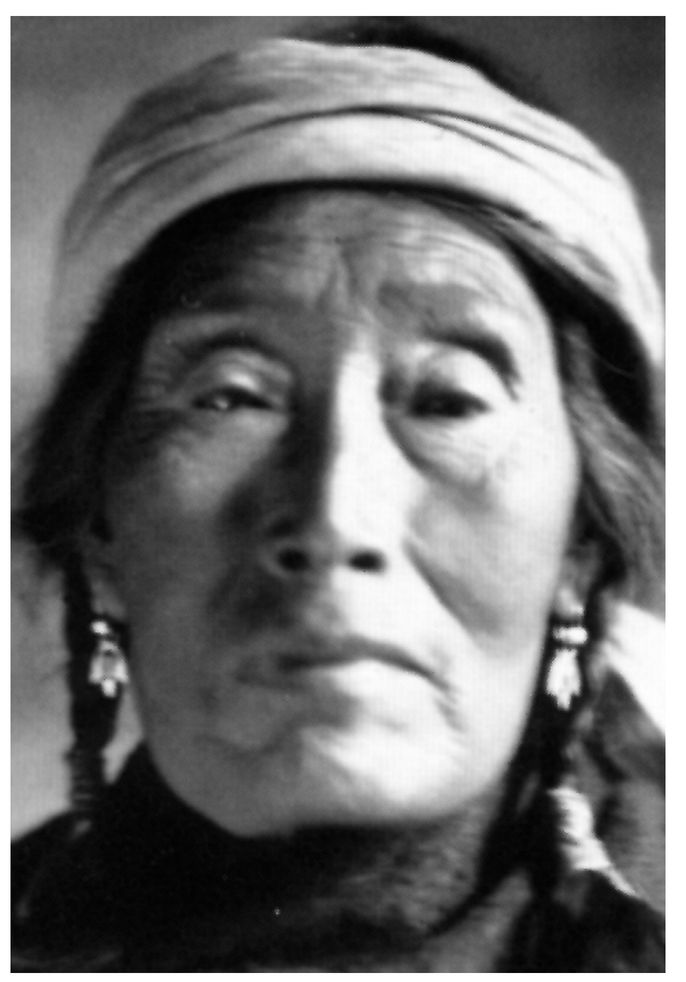

War-ne-la, a Female Kwakiutl Shaman of the Koskimo, British Columbia, 1914. PHOTOGRAPH BY B. W. LEESON, © 1914. VANCOUVER PUBLIC LIBRARY, 14072. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

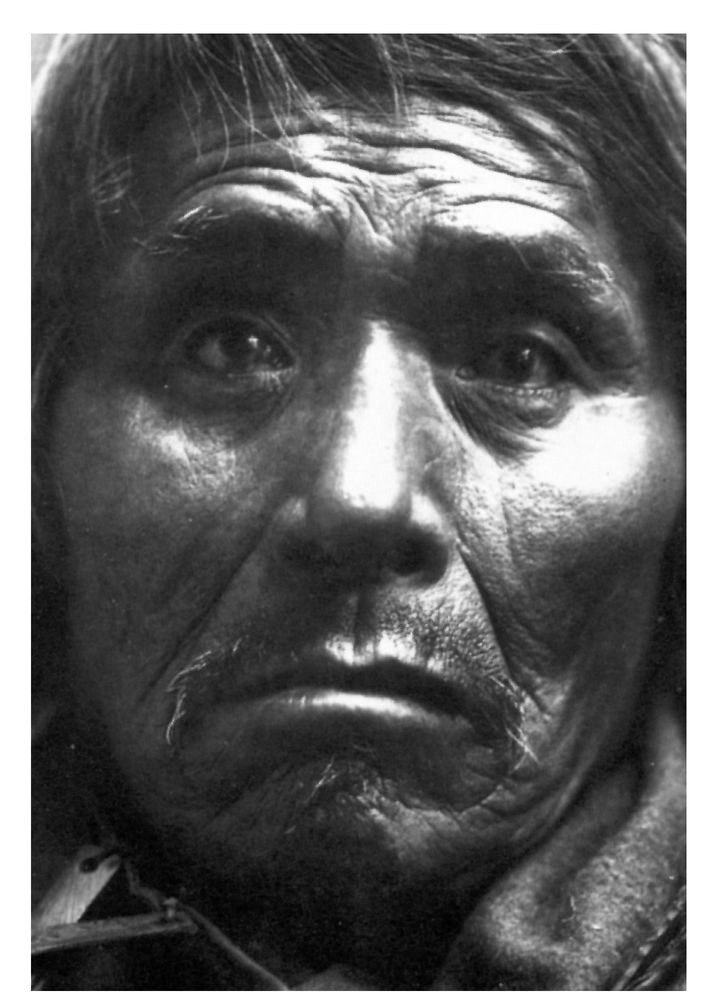

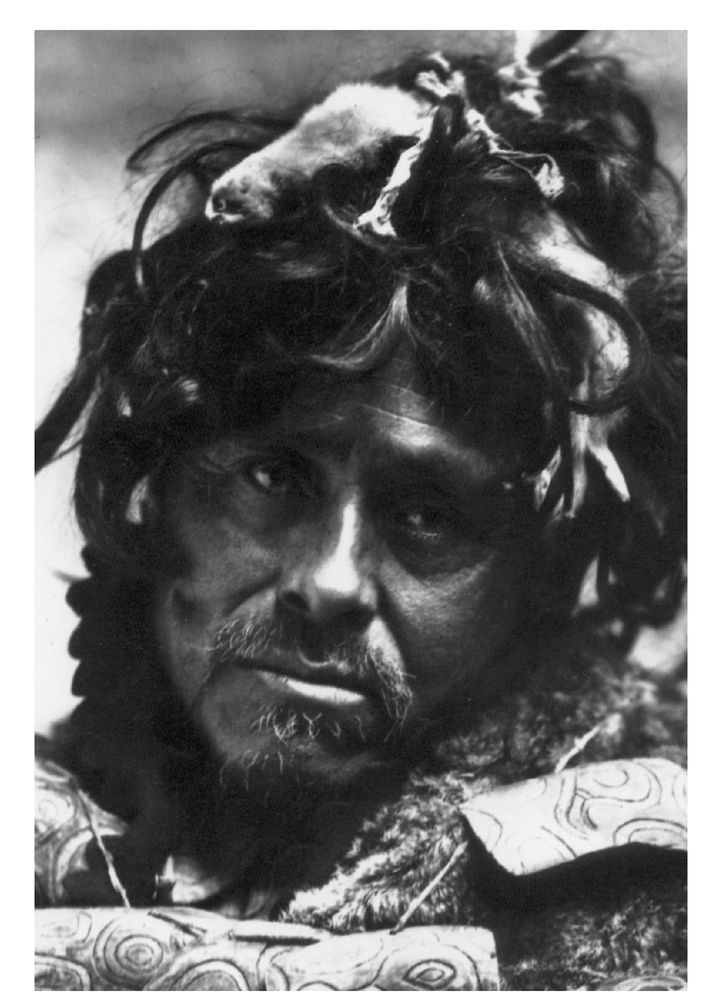

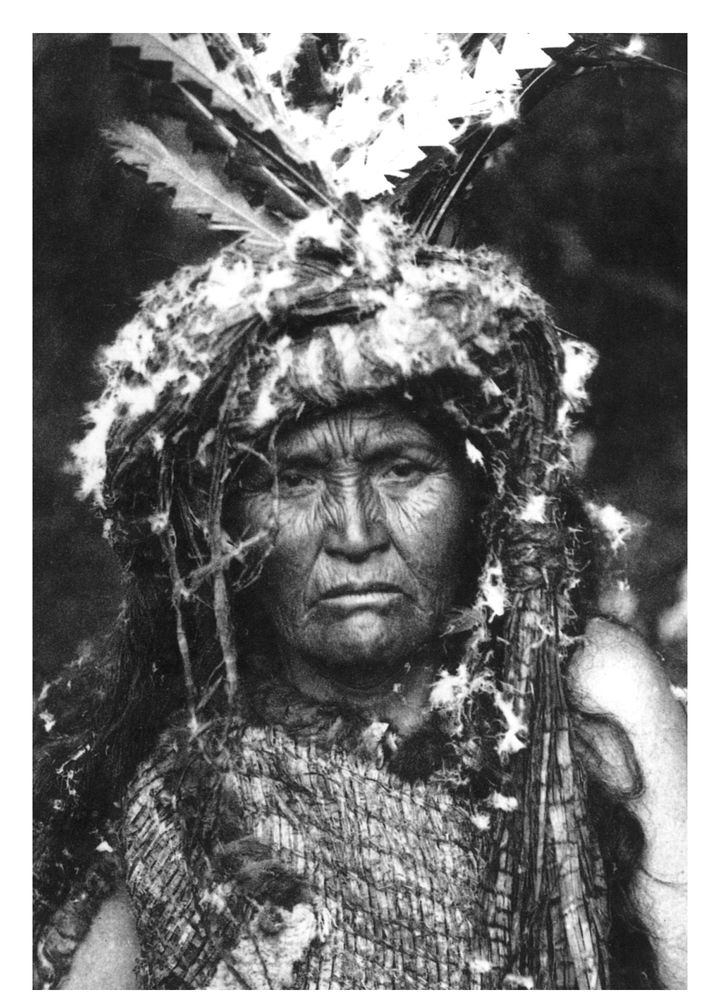

Tlingit Shaman, Juneau, Alaska, © 1900. PHOTOGRAPH BY WINTER AND POND, ALASKA STATE LIBRARY, JUNEAU, 87-247. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

Tlingit Shaman from Taku. PHOTOGRAPH BY CASE AND DRAPER, JUNEAU, © 1905. ALASKA STATE LIBRARY, JUNEAU, 78-215. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

Tlingit Shaman. PHOTOGRAPH BY WINTER AND POND, JUNEAU, © 1900. ALASKA STATE LIBRARY, JUNEAU 87-244. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

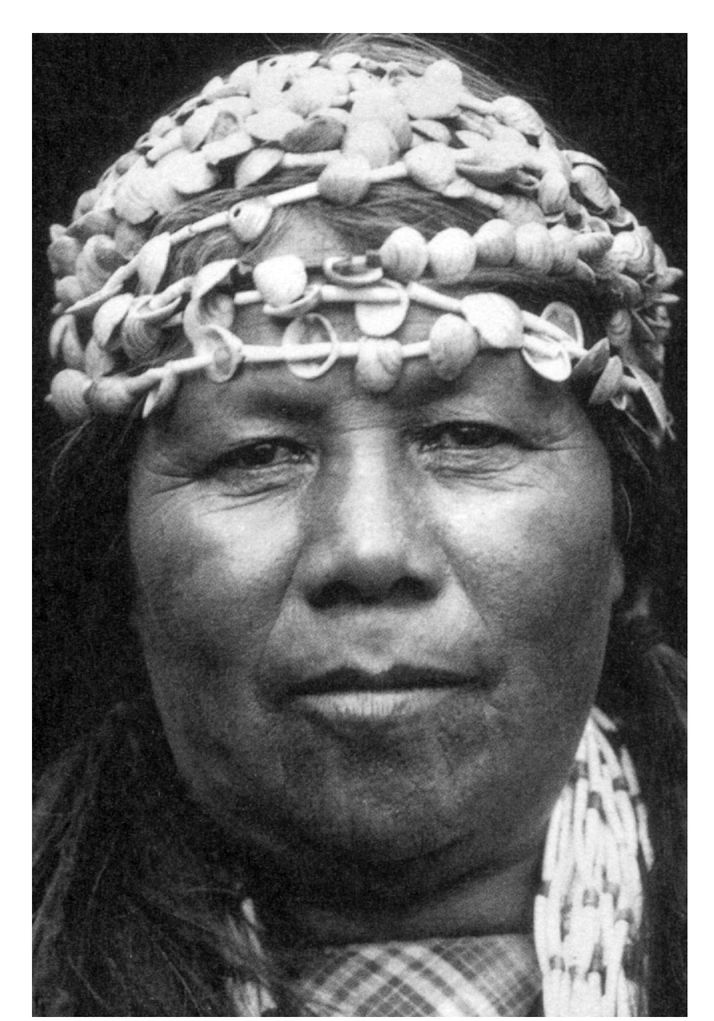

Female Nootka Shaman from Clayoquot Sound, Vancouver Island. PHOTGRAPH BY EDWARD S. CURTIS, © 1914. ROYAL BRITISH COLUMBIA MUSEUM, VICTORIA, PN 5410. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

Hupa Female Shaman, California, 1923. PHOTOGRAPH BY EDWARD S. CURTIS.

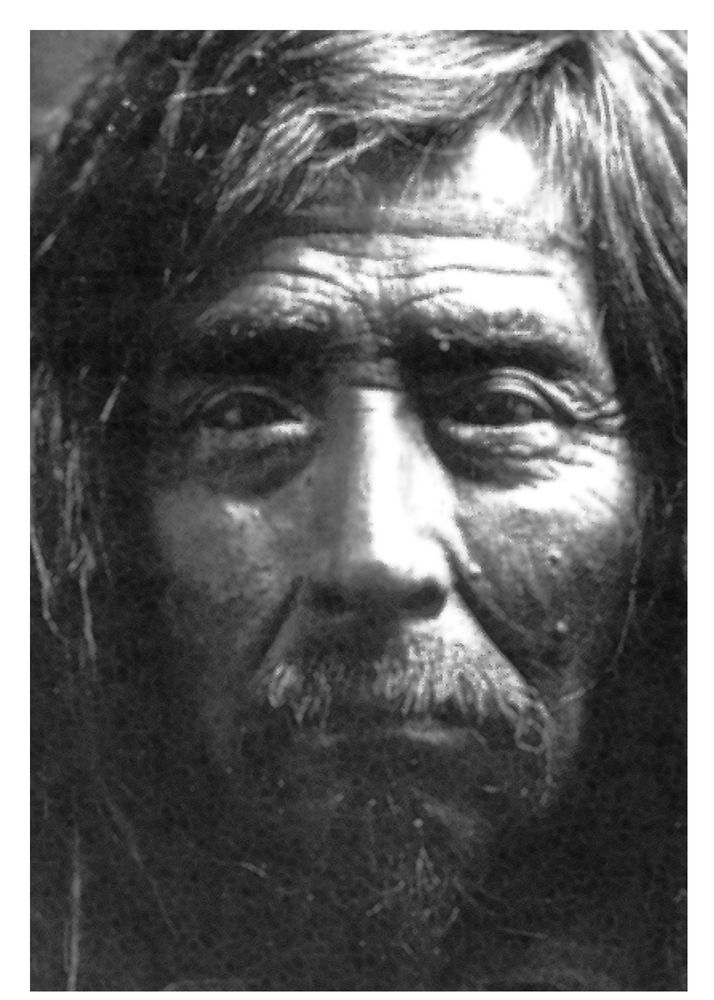

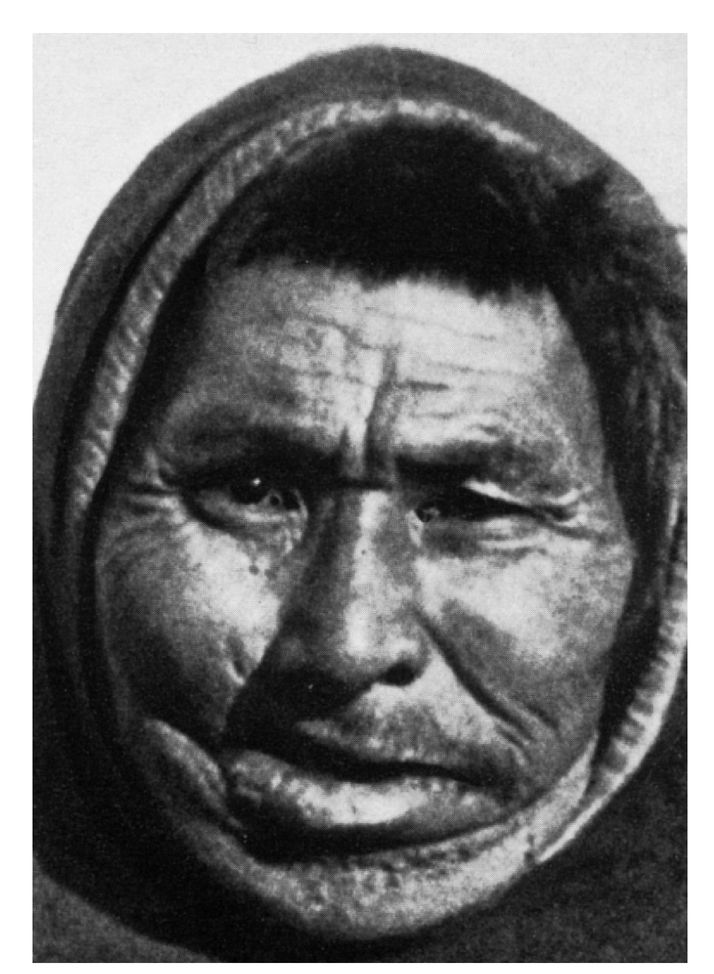

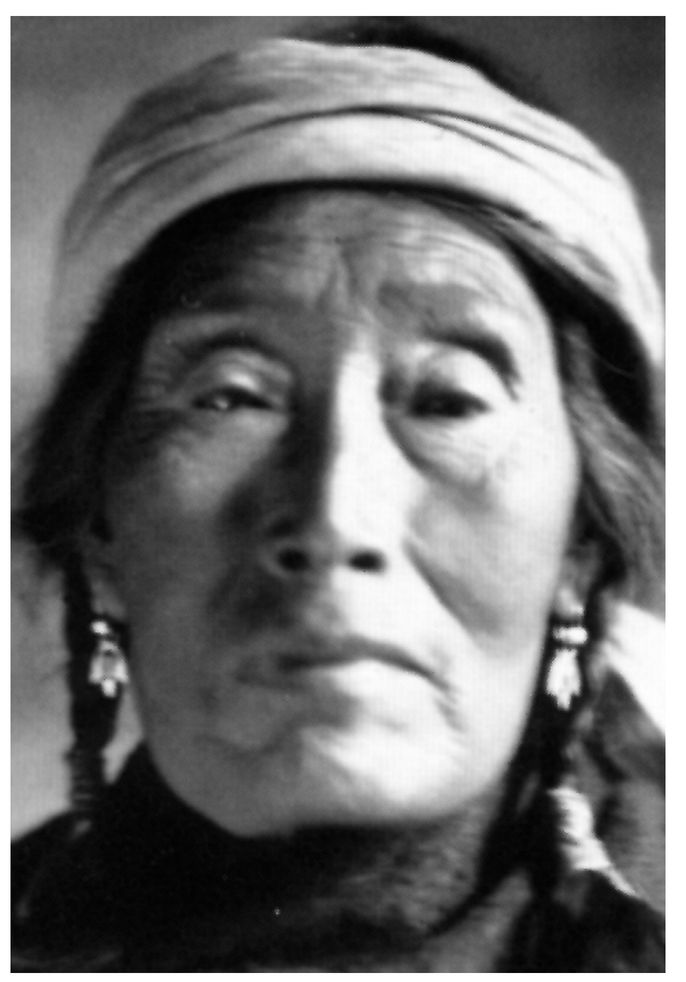

The Eskimo Shaman Najagneq from the island of Nunivak. PHOTOGRAPH TAKEN IN 1924 DURING THE FIFTH DANISH EXPEDITION TO THULE UNDER THE LEADERSHIP OF KNUD RASMUSSEN. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION OF THE HEIRS OF KNUD RASMUSSEN.

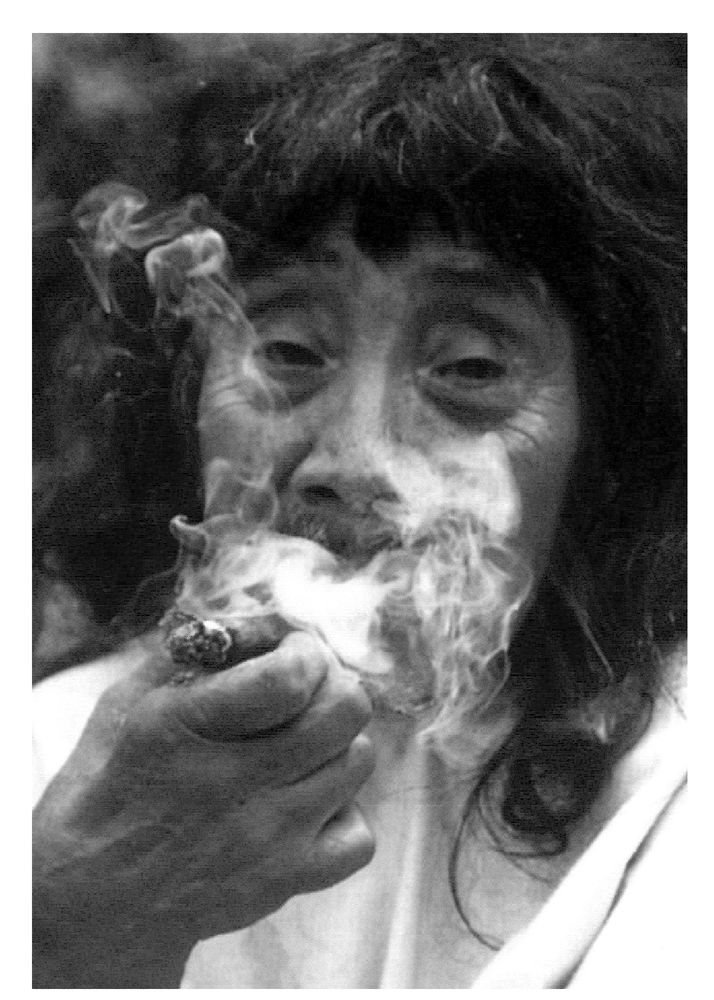

The 104-year-old Lacandon Shaman Chan K’in Viejo, Guatemala, 1991. PHOTOGRAPH BY CINDY KARP. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION OF BLACK STAR, NY.