2

Canton

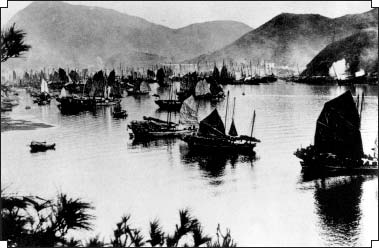

CANTON, CHINA, LATE 1890S (Courtesy of the Second Historical Archives of China)

China, like the purse of a generous man, has endured much.

—Charlie Chan

IT IS HARD to imagine how shocking the scene of rural Canton might have appeared to Ah Pung’s parents when they arrived back in their hometown. The two punishing Opium Wars (1839–42 and 1856–60), combined with the brutal Taiping Rebellion (1851–64), had ravaged the countryside in the Pearl River Delta, which sprawled out to the South China Sea. With endemic poverty that was decimating the population, hardscrabble peasants were living lives that were, to use a Chinese expression, niuma buru—worse than those of cattle and horses.

Little Ah Pung’s ancestral hometown, Oo Sack, a small village in Hsiangshan District, south of Canton on the western bank of the Pearl River, was no stranger to this devastation. Later, the district would change its name to Chungshan, in honor of its best-known native son, the founding father of the Republic of China, Sun Yat-sen, who, like Ah Pung, would come of age in Honolulu.

There is, sadly, no record of Ah Pung’s life in Oo Sack. But one of his contemporaries, Chung Kun Ai, provides in his memoir, My Seventy Nine Years in Hawaii, a description of this pattern of dreary subsistence in rural Canton in the 1870s. Chung, better known as C. K. Ai, was born in 1865, a few years before Ah Pung, in Sai-San, a short distance northwest of Oo Sack. Despite the difference in spelling (thanks mostly to the crude imagination of U.S. customs officers, who baptized millions of immigrants by assigning last names they had acoustically approximated from Chinese, Yiddish, and Polish alike), “Chang” and “Chung” are transliterations of the same Chinese character. Chang Apana and Chung Kun Ai, in other words, share a family name, even though there is no record to indicate they are immediately related. Later, orbiting in the same microcosm of Honolulu’s Chinatown, with Apana as famous cop and Ai as leading businessman, it is possible that their paths might have crossed again.

Poverty, as Ai recalls, plagued the shabby villages scattered around the delta south of Canton. Bombed by British battleships during the Opium Wars and scorched in what historians have characterized as “the most destructive civil war in the history of humanity,”1 this area suffered from famines, bandits, and epidemics. Adding to the miseries were the constant fights between the Punti (local people) and the Hakkas (guest people) over land possession. Feuds between clans could turn bloody. A Chinese immigrant recalled the bitter memory of being forced to flee from the violence and turmoil:

In a bloody feud between the Chang family and the Oo Shak [i.e., Oo Sack] village we lost our two steady workmen. Eighteen villagers were hired by Oo Shak to fight against the huge Chang family, and in the battle two men lost their lives protecting our pine forests. Our village, Wong Jook Long, had a few resident Changs. After the bloodshed, we were called for our men’s lives, and the greedy, impoverished villagers grabbed fields, forest, food and everything, including newborn pigs, for payment. We were left with nothing, and in disillusion we went to Hong Kong to sell ourselves as contract laborers.2

Cantonese from this area, out of economic necessity, were among the first to sell themselves into the dreaded coolie system. Like Irish peasants after the potato famine, they were the most active in venturing overseas during the second half of the nineteenth century. A government report of the time noted: “Ever since the disturbances caused by the [bandits], dealings with foreigners have increased greatly. The able-bodied go abroad. The fields are clogged with weeds.”3

In Ai’s plain language, we sense the dearth of materials and supplies in the life of these villagers left behind:

Ours was such a small village that we had no stores or restaurants. A small local shop supplied such often used items as sauce and bean-curds, but for the other household and kitchen items that we needed we must wait for the market days to come around.4

On so-called market days, vendors convened at a particular village; the markets rotated among adjacent villages. There was simply not enough commerce to justify maintaining a regular store in one location and keeping it open daily. Market days were the few occasions when children like Ai and Ah Pung could, if allowed by their family budget, purchase a taste of life outside of its impoverished norm.

Ai, coming from a well-to-do family of country gentry, did manage to experience such temporary relief. Writing his memoir in his eighties, when he had retired comfortably to Hong Kong, the Hawaiian business tycoon remembered with almost boyish delight the bowls of soup he had gulped down with such eagerness in the early years of his life:

As Yung Mark was but a mile and a half from our village, I would visit Yung Mark on market days and spend money on a bowl of rice-soup of fish, pork, or chicken. The cheapest was fish rice-soup, at sixteen cash a bowl. After I have had my fill of rice-soup, I would return home.5

Ah Pung, however, had no chance for even as simple a treat as a bowl of fish- or meat-flavored soup. His family was poor, as evidenced by his lack of schooling—any family that could afford it would have been obliged to send their kids to school at that time, or in almost any other period of Chinese history. Ah Pung, in fact, never learned to read in either Chinese or English, even though later in life he taught himself to read Hawaiian. Toys were rare in a family like his.

It is worth noting that even a full century later, little had changed. When I was growing up, for example, in a small village in the waning days of Mao’s China, my “toys” were mud-pies, tadpoles, ants, fireflies, grasshoppers, and whatever luckless insects fell into my hands. Occasionally I could catch a fledgling sparrow learning to fly if I suddenly clapped my hands and yelled loudly. The frightened young bird would fall to the ground and make a good, hapless pet—but only for a few days, since caged sparrows have a fiery, rebellious temperament and do not survive for long.

Such were the simple, rustic delights of childhood in rural China, both for Ah Pung and for me.

There would be endless chores that even a three-year-old such as Ah Pung would have to share: gathering fallen tree leaves and twigs for kitchen fuels, collecting animal droppings for fertilizer, keeping birds and animals away from grain drying on the ground, and so on. The slightly older kids would have to babysit their siblings, wash dishes, do laundry, herd water buffalo, or simply work in the fields like adults.

In such a harsh environment, a child prone to accidents and disease would be lucky to grow to maturity. Child kidnapping was a common, daily fear in Ah Pung’s day. Occasionally, when a famine broke out, cannibalism might become the last resort for families on the brink of starving to death; they were forced by necessity to make exchanges with other equally desperate families so they could at least avoid eating their own children or siblings.

The decade of the 1870s, as Ah Pung’s parents would come to realize, was a particularly dire time for China. Teetering in the wake of the crushing wars, the Manchu regime could no longer maintain the imperial façade of the Middle Kingdom. Still four decades from its collapse but already in decline, the Ching dynasty understood that more troubles loomed on the horizon. Among them were fears that the repeated military and economic invasions by the Western powers would make the empire, increasingly carved up through territorial concessions, resemble nothing more than a juicy melon. Regional and nationwide rebellions accompanied this imperial plunder as well. The entire situation was exacerbated by the scourge of opium, which the British had imposed on the Chinese, resulting in an addiction problem for millions.6 Not surprisingly, the Chinese carried this addiction to Hawaii, where Chang Apana, as a cop, would be charged with eradicating this vice.

Hoping for a better future for their offspring, Ah Pung’s parents decided to send him out of the country. Even though they themselves had not had any luck in Hawaii, the islands were an unquestionable improvement over rural Canton in a country on the verge of political and moral collapse. Ah Pung’s uncle, later known in Hawaii as C. K. Aiona, had signed aboard a ship to try his luck in the Sandalwood Mountains. So, at the age of about ten, in 1881, Ah Pung accompanied his uncle and sailed for his birthplace.

The young boy had little clue about what lay ahead. Having left Hawaii at three, he might possibly have had faint memories of the soaring cliffs, verdant valleys, and kaleidoscopic flora and fauna. But more than that? Not likely. As the ship departed from Whampoa Harbor and drifted down the Pearl River, Ah Pung watched the wretched countryside float by. Straw huts—not unlike the one in which he had been born ten years earlier in Hawaii—dotted rural Canton’s bleak landscape, like bird nests perched on barren trees in the dead of winter. Here and there, a skinny water buffalo would be toiling in rice paddies at a languid pace. Rent from his parents at this impressionable age, Ah Pung would never see China again.