3

Paniolo, the Hawaiian Cowboy

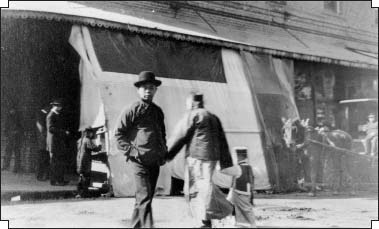

CHINATOWN, HONOLULU, LATE 1890S (Courtesy of Hawaii State Archives)

You gaze at this cattle ranch from high on the misty heights of Hawaii’s Mauna Kea, and from the volcano’s sloping shoulder you see 227,000 acres, a breathtaking vista spread out on the highlands of this great mountain. A soothing wind drifts from the mountain and cools the lava wastes. Seemingly limitless, the area includes forests, valleys, seashores, plateaus, meadows, hills, streams, and canyons. This is the sprawling, mysterious, majestic Parker Ranch, with the largest Hereford herd in the world.

—Joseph Brennan, The Parker Ranch of Hawaii, 1974

THE GLIMPSE OF the island of Oahu at the end of a forty-day sea voyage provided a stark contrast to Ah Pung’s last view of China. As the boat neared the harbor, epic peaks soared into towering clouds and expansive azure. In deep clefts of lush green, waterfalls streaked down like the long, silvery hairs of a mermaid. Under the tropical sun, the Diamond Head promontory humped like the gnarled back of a giant whale, softened only by the wavy line of palms stretched out along the white beaches of Waikiki. The amphitheater of Punchbowl, the future, fictional home of Detective Charlie Chan, stood majestically at the center of the butterfly-shaped island, beckoning the new arrivals.

Almost all travel writers worth their salt have spoken of the romance of arriving in Hawaii. They often evoke a timeless scene. Bands play aloha music, native girls in grass skirts dance hula, and matronly women in colorful holokus hang leis around the necks of visitors. But for the Chinese coolie laborers who had been packed in the crowded steerage with no privacy or comfort for weeks, this moment of landing was one of utter confusion, anxiety, and humiliation.

Trudging down the gangplank in a stream of blue cotton, they were greeted not by sirens chanting but by immigration officials shouting incomprehensible commands and questions at them. In frustration, the laborers, coached by their booking agents, shouted back the names of their intended plantations. These were the only two or three English/Hawaiian words they knew or would ever need to know: “Puunene Maui!” “Waialua Sugar Company!” “Naalehu Hawaii!”

After they had been identified by the plantation representatives, a bango—a numbered metal tag on a chain, hardly a welcome lei—was placed around each of their necks. Then, like cattle heading to market, they were piled into the waiting wagons and taken to their ultimate destinations.1

Ah Pung, along with his uncle and other laborers, was sent to a plantation in Waipio, his birthplace. The already-sketchy paper trail that follows Ah Pung’s early life unfortunately stops here, at his return around 1881. When he emerges again in our story with any certainty—in 1891, to be exact—Ah Pung, having adopted his official name of Chang Apana, would already be a young man. Despite the absence of reliable information, there exist personal recollections and circumstantial accounts that enable us to piece together a plausible picture of Apana’s life during this time.

In these ten or so formative years, we are certain that Apana did at least two things: first, he learned to handle horses, and second, he became a stableman for the wealthy Wilder family in Honolulu. There are accounts of Apana winning the title of the best horseman among the Chinese in Hawaii.2 Later, as a policeman, he would always wear a cowboy hat and carry a bullwhip, reminders of those tough riding days. In his funeral procession in 1933, thronged by hundreds in Honolulu, a handler led a white horse without a rider. This was said to be the mount used by Apana while on active duty in the Honolulu Police Department.3

Horses, then, apparently played an integral role in Apana’s illustrious career, so, to know the true color of our future “supersleuth,” one needs some familiarity with the hardscrabble life of those dashing, devil-may-care paniolos, the Hawaiian cowboys.

NOT UNTIL 1803 did the first horse arrive in Hawaii, aboard the China trader Lelia Bird. Captain Richard J. Cleveland brought a stallion and two mares from Baja California as gifts for Kamehameha the Great. They caused quite a stir among the natives, who crowded the ship’s decks to see these bizarre equine creatures. Noticing their quizzical looks, a sailor jumped on the back of one of the horses and did a demonstration of galloping. The king, however, failed to show any interest. He took a careless look at the horses and made a remark that greatly disappointed Cleveland. He could not, the king said, perceive that the ability to transport a person from one place to another, in less time than he could run, would be adequate compensation for the food the animal would consume and the care it would require.4

The king, however, was alone in his nonchalance. Other groups, like the Native Americans a few centuries earlier, had quickly adopted these continental imports as their daily companions. In the words of a catalogue distributed by the Hawaiian Humane Society, “From the day the first mare awed Kona residents in 1803, native Hawaiians were hooked on horses.” Half a century later, as the Pacific Commercial Advertiser reported in 1864, “The passion of the Kanaka, male or female, for horses is the most marked trait in their character.”5

The horse, however, is only one of the two animals essential to the life of a cowboy, the cow of course being its plodding companion. Cattle had first arrived in Hawaii a decade earlier than horses. In 1793, Captain George Vancouver, the famous English circumnavigator, brought five cows as gifts to Kamehameha the Great at Kealakekua Bay on the Big Island. Vancouver had originally loaded nine cattle—two bulls and seven cows—aboard the Discovery in Monterey, but the animals fared poorly on the long voyage from California. A bull and a cow died en route, and the remaining bull expired soon after landing. It was a glancing blow to Vancouver’s hope to establish a breed of cattle in the islands.

Learning from his blunder, Vancouver brought three bulls and two more cows the following year, this time in good condition. He convinced the king to declare a kapu (taboo) upon all the cattle for ten years and to punish by death anyone who might injure or kill any of his animals. Thus, protected by royal decree, the bovines grazed freely on the grassy upland range of Waimea. With the aid of natural feed and friendly climes, the animals multiplied, perhaps even more rapidly than the king had anticipated. By 1813, only twenty years after their introduction, thousands of maverick cattle were roaming the plains, valleys, and forests of northern Hawaii.6

The wild beasts became a nuisance to the natives, munching crops of potatoes, ravishing taro patches, and trampling forest growth. The natives were forced to build stone fences to ward off the invading hordes. In some regions, branches of koa trees were cut and twisted into crude fences. The cattle were also a menace to local residents, who had to avoid thicketed areas where wild bulls reigned supreme and were prone to attack human intruders.7

The problem with these roving herds created a golden opportunity in 1815 for a keen-eyed young New Englander, John Palmer Parker, who, as Hawaii’s first cowboy, would build the largest cattle dynasty west of Texas. Born on May 1, 1790, near the Charles River in Newton, Massachusetts, Parker seemed destined to sail the high seas—his father had inherited the family whaling-ship business, while his mother was a descendant of shipyard owners and operators.8 Arriving in Hawaii aboard a sandalwood trader in 1809, Parker was smitten by the beauty of the tropical isles and decided, like Herman Melville in the Marquesas twenty years later, to jump ship.

With the help of friendly natives, Parker built a small hale (house) and tilled an area around the hut to plant seeds. He learned the Polynesian language and acquainted himself with the king. Kamehameha gave the young haole (white man) a job tending the royal fishponds.9 Soon the seafaring itch set in again, and in 1811, when a New England merchant ship passed through Hawaii, Parker signed on for a voyage to China. Unfortunately, the ship, sidelined by a British blockade, was stuck in Canton during the War of 1812.

Finally returning to Hawaii in 1815, Parker realized that even though wandering the high seas was his calling by birth, he would prefer a more secure life. With the longhorns running wild on the island, Parker recognized an opportunity where others only saw nuisance and hazard. He made a business proposal to Kamehameha, asking the king to allow him to shoot cattle. Deep in debt due to his ill-managed sandalwood trade, Kamehameha was willing to give a second chance to the haole who had played hooky from the fishpond job. He hired Parker as his konohiki (agent) for the supplies of “garden vegetables, taro, meats, and hides for local and foreign consumption,” making him the only person for whom the twenty-two-year-old kapu on cattle was lifted.10 Armed with a musket, the tall, rawboned Parker became, if you will, a pre-Hollywood John Wayne. He spent long days riding into forests and valleys and shooting the king’s cattle. It was hard and dangerous work, for the animals were wild and vicious and would often, like Ahab’s Moby Dick, hunt the hunter.

In this gruesome slaughter business, Parker was fortunate to have a partner, Jack Purdy, who was easily Parker’s match in sturdiness and courage. Purdy had come to Hawaii aboard a whaling vessel and had, like Parker himself, jumped ship at Kawaihae, on the Big Island. He had also married a Hawaiian woman and had children who all became paniolos. Mary Low, one of Parker’s great-granddaughters who grew up at the ranch, later recalled stories she had heard about tough Jack Purdy. One tale concerned an Englishman named Brenchley, a man of fortune and a great traveler of Herculean strength. When in Hawaii, Brenchley took Purdy as his guide and claimed that he could do anything or go anywhere that the guide could. One day Purdy proposed that they go out with only their guns and blankets. They rode toward Mauna Loa and subsisted only on geese, ducks, and plovers. Finally they ran out of gunpowder, which worried Brenchley. Purdy took him to a swamp and told him to get in; Brenchley sank to his knees. Telling him to stay there, Purdy disappeared into thick brush near the swamp. Soon, from the brush came a wild bull with an eye of fire and a tail erect. The animal charged toward Brenchley, plunged into the swamp, and stuck fast. “There’s our dinner!” yelled Purdy. He gathered some twigs and tied them into two bundles. He put one bundle on the mud and stepped on it. “Then he cast the other bundle ahead and stepped on that, picking up the first bundle and casting it before him. In this way, he reached the bull and, drawing his knife, cut the animal’s throat and soon sliced off some pieces of beef. Returning to firm ground in the same manner as he had gone to the bull, he kindled a fire and in a short time invited Brenchley to dinner.”11 After this, Brenchley had to concede that he had finally met a man who surpassed him in daring.

As a team, Parker and Purdy would trek into the ruggedest regions to obtain beef. Each time they shot a bull or cow, they would “cut away the meat from the carcass and haul it to where [they] could salt it and pack it in barrels.” Faced with the generous bounty of nature, many would have succumbed to greed and engaged in mindless killing and reaping of bonanzas, as has occurred with the near-extinction of the whales in the Pacific, buffalo on the American plains, and elephants in Africa. But Parker was no Captain Ahab, no Mr. Kurtz. He was a wise man with a shrewd business sense. As the king’s agent, he took his salary in the form of selected live cattle, which enabled him to choose the best breed for domestication. Very soon he had tamed and fenced in enough herds to start a ranch of his own.12

The primary market for beef was not the Hawaiian natives, whose traditional diet had been confined to fish, pig, and poi (taro paste). The best customers were the whaling fleets that made island calls to winter the crew and replenish their supplies. As the hunt for the ocean’s leviathans intensified at a maddening pace, the demand for Parker’s beef increased, soon surpassing what his small team could procure from the great wilderness or from his growing ranch. More help was needed.

Still strapped for cash because of his expensive purchases of luxury items on credit, Kamehameha agreed to Parker’s request and sent for help from California. Help came in the form of a team of colorful Spanish vaqueros, who one day arrived on the pier clad in woolen ponchos, slashed leggings, brightly colored sashes and bandannas, and floppy sombreros. These artisans from the mainland taught the Hawaiian natives everything they needed to know about horses and cattle, and every skill of ranching: how to capture wild horses and break them to saddle, how to lasso raging bulls, how to tan leather with tree bark, how to braid rawhide quirts and lariats, and how to build saddles. Not only were the natives eager to learn the arts of the cowboy, they also were quick to emulate the exotic costumes and the lifestyle that came with the profession. After calling the vaqueros “the Españols,” they referred to themselves as “paniolos,” a variation of the former word.13

In short order, the Parker Ranch grew rapidly, and so did the number of paniolos, who would soon include Hawaiians, Caucasians, Asians, and other mixed-race men. After John Parker died in 1868, the vicissitudes of the ranch rose and fell, as do all dynasties in history, throughout the remaining decades of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. But the ranch has always remained under the control of the Parker family, making it even today the second-largest family-run ranch in the United States.

IT WAS AT the Parker Ranch in Waimea that young Chang Apana learned and honed his cowboy skills. Although no verifying record has been found, at least two reliable sources place Apana at the ranch. Chester A. Doyle, a court interpreter who had worked closely with the Honolulu Police Department, described in a 1935 letter a dinner meeting he had once hosted for Earl Derr Biggers. According to this letter, addressed to the editor of the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Biggers had arrived on the island to scout for materials for his next book, and Doyle threw a dinner party at his home in honor of the famous Charlie Chan novelist. Among the twenty or so guests was Apana, who, according to Doyle, spoke about his days at the Parker Ranch.14

Doyle’s letter was full of factual errors, many of which were disputed by Helen K. Wilder in a letter subsequently published in the same newspaper a month later. Wilder differed with Doyle on many points except for one, that Apana did work at the ranch in Waimea.15

The Parker Ranch, when Apana spent time there in the late 1880s and early 1890s, was plagued by poor management. After John Parker’s death, ownership of the ranch passed down to his descendants. Troubles loomed when the cattle dynasty reached Samuel Parker of the third generation, who preferred the leisurely life of a playboy to the hard work of a rancher. A close friend of King Kalakaua, who was dubbed “the Merry Monarch” for his love of life’s pleasures, Samuel Parker spent more time hobnobbing in the royal court than running the ranch. Not surprisingly, the business suffered.

Nonetheless, work went on for the hundred or so hired paniolos. Joining this most colorful group, young Apana certainly acquired a great knowledge of ranching. The 227,000-acre ranch, lying in the northwest of the Big Island, high up on Mauna Kea’s bare volcanic slopes, had breathtaking vistas of natural beauty as well as rough terrain unsuitable for the faint of heart. From sunrise to sunset, Apana joined other paniolos in herding, cutting, holding, roping, throwing, branding, castrating, inoculating, ear-clipping, medicating, sorting, loading, and shipping.16 Even after sundown, there would still be plenty of odd jobs to do: tending to the horses, caring for the saddle and tack, repairing the lassos, chopping wood, and more.17

A cowboy’s life demanded courage and built character. The experience would have a lasting effect on Apana, and for the rest of his life he was known as a top-rider and hunter—fearless, dashing, devil-may-care. From dress to talk, from weapon to walk, the future “supercop” would maintain a paniolo’s way of life. He would always wear a cowboy hat and carry a bullwhip that he had fashioned himself, just as a paniolo handcrafts his own lasso and saddle. Dark and sinewy like a bull, he walked straight and fast, with an energetic gait. According to his daughters, Apana could “tell time down to the minute by observing the shadows that the sun cast.” And he kept the same schedule of getting up and going to bed every day, like a clock. In his “high shrill voice,” he spoke fluent Hawaiian, the crisp syllables popping like firecrackers.18

By the time Helen Wilder hired him, in 1897, as the first officer for the newly founded Hawaiian chapter of the Humane Society, Apana the paniolo was ready for the proverbial wide, wild world.