6

Chinatown

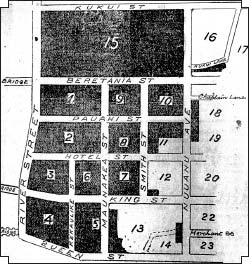

MAP OF CHINATOWN, HONOLULU, WITH DARKENED BLOCKS INDICATING AREAS BURNED IN THE 1900 FIRE (Courtesy of Hawaii State Archives)

Aromatically and mysteriously and defiantly different from all the rest of [the city].

—Simon Winchester, referring to Chinatown1

TO CALL THE architecture of Honolulu’s Chinatown eclectic in the waning days of the nineteenth century would be a misnomer; in fact, it was filled with “wretched jumbles,” as one observer remarked.2 A warren of structures circumscribed in four directions by River Street, Nu’uanu Avenue, Queen Street, and Beretania Street, Chinatown sprawled over a dozen blocks like an overbuilt checkerboard on the verge of tilting into the harbor. Evolving from just a few waterfront stores in the mid-1850s, it eventually occupied thirty-seven acres, with claptrap restaurants, grocery stores, laundries, bakeries, pharmacies, slaughterhouses, warehouses, whorehouses, gambling parlors, and opium dens in littered, claustrophobically congested streets. When Chang Apana started walking that beat, Chinatown was already a golden phoenix, albeit a sodden and soiled one, having fully sprung from the 1886 conflagration that had, temporarily, eradicated its filth in the eyes of authorities.

The fire of April 18, 1886, was said to have started in a back room located over a Chinese restaurant in a two-story wooden building. Investigators claimed that “about twenty Chinese men were gambling in the room when an argument broke out and in the ensuing scuffle a stove was knocked over and its fire ignited the building.”3 Whether or not this single incident was the true spark of the fire, the allegation jibed well with anti-immigrant sentiments on the island as well as the mainland. The Great Chicago fire of 1871, for instance, had also been blamed on an immigrant: infamous Irish-woman Catherine O’Leary, whose milk cow had allegedly knocked over an oil lamp, starting the inferno that destroyed much of the city. In a popular 1881 comic poem, “The City That a Cow Kicked Over,” satirist Anna Matson identified the poor working woman, or the cow (the pun in the title unlikely lost on the readers), as “a sinister and little known ‘other’ that might in fact bring down the entire city.”4 As the poem runs,

These are the Ruins—sad to tell!

Towards which those Gifts were poured pell-mell,

By rail and river and ocean’s swell,

For the beggared people—Lawk-a-deary!

Who had left their homes so bright and cheery,

Wrapped in flames from that Hovel dreary,

That sheltered the famous Mrs. O’Leary,

That milked the Cow forlorn and weary,

That kicked the Lamp, that started the

Fire that burned the City.

Likewise, haole-controlled Hawaiian newspapers invariably linked the 1886 Chinatown fire to what they called “the pernicious gambling habits of the Chinese.” The fire caused $1,750,000 in damage to property and left more than 7,000 Chinese and 350 native Hawaiians homeless. The next day, King Kalakaua, who had personally directed the efforts to put out the fire and had even caught a nasty cold in the process, convened a Privy Council meeting to set up a relief fund and make plans for rebuilding. Although the fire was a nightmare for the predominantly Chinese residents, it was, in the words of one historian, “a city planner’s dream: some thirty acres of nothing, on which to exercise imagination, artistry, and the financial muscle of the taxpayer.” Hawaiian newspapers also embraced the tragedy as an opportunity. “Sweet and Clean,” ran a headline, referring to what remained of Chinatown. An editorial in the Pacific Commercial Advertiser urged the city to “turn a natural disaster into an ultimate blessing.”5 Despite the overt racism expressed in these reactions, Honolulu, still under the rule of a benevolent monarchy, was far more tolerant than mainland American cities, which often took advantage of disasters like this to further segregate immigrants. After its 1906 earthquake and fire, for instance, San Francisco rezoned the city blocks in an attempt to drive Chinatown to the outskirts or beyond.

According to the rebuilding plan, Honolulu was to survey burned districts, make improvements, widen and straighten streets, regulate construction, and enforce sanitation rules.6 But bureaucracy and corruption inevitably got in the way of city planning, and the new Chinatown that emerged after reconstruction, as far as fire safety was concerned, was another disaster waiting to happen.

Disaster was not long in coming. In January 1900, less than a month into the new century, the bubonic plague broke out in Chinatown. With victims marked by swollen lymph nodes in the armpit, groin, and neck, the bubonic plague was considered the same infamous Black Death that had devastated the urban populations of Europe in the mid-fourteenth century. Hawaii’s Board of Health embraced the counsel of doctors who claimed that Hong Kong had prevented the plague’s spread by burning all buildings in the infected areas, thereby killing plague-carrying rats.

Accordingly, on January 20, the Board of Health brought in fire engines and started burning condemned buildings within infected, quarantined areas. The fire was supposed to be controlled, but it soon got out of hand. By midmorning, the wind changed direction and whipped up gusts, which sent sparks flying everywhere. Adjacent buildings, all constructed of wood save for one church, went up in flames. By two o’clock that afternoon, all of Chinatown had become a doomsday inferno. It was many days before the embers cooled, and the whole area was transformed into a wasteland.7

The great conflagration left 4,000 people homeless, with a financial loss in excess of $3 million. The destroyed area, which comprised more than a dozen blocks, was enclosed with a high board fence to prevent the spread of the plague. For months, the formerly bustling thoroughfares and teeming markets stood as quiet as a graveyard. It was forbidden turf. Not even a rat or an animal could be seen moving there.8

CHINATOWN AFTER THE 1900 FIRE (Courtesy of Hawaii State Archives)

Rebuilding did not commence until May 17, when the soil was finally pronounced clear of plague bacilli. It took another year or so for Chinatown to regenerate, with improved building structures, sanitation systems, water supplies, and road plans. Regaining its charm and vitality after two calamities, Chinatown was finally ready for the new century—one in which the dominating social issue would be, in the words of W. E. B. Du Bois, “the problem of the color-line.”

It is a common assumption that Chinatowns in major U.S. cities around the turn of the twentieth century were breeding grounds for crime and squalor. The mere mention of “Chinatown” immediately calls up images of pestilential slums, opium dens, filthy brothels, and gambling parlors, all crowded by Chinamen with their long, plaited queues and baggy pantaloons. But most people do not know that China towns were also hotbeds for the early twentieth century’s Chinese revolution. Honolulu’s Chinatown in particular played a crucial role in the birth of modern China. It was here that Sun Yat-sen, founding father of the Republic of China, came of age and struck the first spark of revolution, which would put an end to four thousand years of monarchical rule in China.

Sun Yat-sen was, as noted in chapter 2, born in Hsiangshan District, in the village of Choy Hang, about twenty miles north of Chang Apana’s ancestral village, Oo Sack, on November 12, 1866. In 1879, at the age of thirteen, Sun left for Hawaii to live with his elder brother, Sun Mei, who had established himself as a successful businessman. After clerking in his brother’s store for a few months, Sun attended the prestigious Iolani School in Oahu. Though he did not know a word of English, he was a fast and diligent learner. When he graduated from Iolani three years later, Sun was second in grammar and received a prize from King Kalakaua. He then studied for a year at Oahu College (later renamed Punahou School), where he learned about Christianity. Shocked that his younger brother might betray Chinese culture for a “foreign” religion, Sun Mei sent him back to China. But the exposure to Western culture and ideas had already left an indelible mark on Sun Yat-sen’s mind. As soon as he returned to Choy Hang, he created a scandal by vandalizing the wooden statues of the protective deities at the village temple. Within two years, he would be baptized by an American Congregational missionary, Dr. Charles Hager, in Hong Kong.9 In his later recollection, Sun would claim Hawaii, not the provincial Choy Hang, as his spiritual hometown. “This is my Hawaii,” he said, “Here I was brought up and educated; and it was here that I came to know what modern, civilized governments are like and what they mean.”10 After his first extended stay in Hawaii, Sun would make five more trips to the islands during his lifetime, chiefly to develop political organizations, raise funds, and recruit volunteers to participate in uprisings in China.

On a dark, moonless night in November 1894, a meeting was held at a quiet bungalow on Emma Lane, within a stone’s throw of Chinatown. Led by Sun, about twenty Chinese, including C. K. Ai, lined up for an initiation ceremony. One by one, they placed their hands on the Bible and asked God to witness their oath to “drive away the Tartars, recover China for the Chinese, and establish a republic.”11

This clandestine meeting was a milestone in Chinese history. Hsing Chung Hui (Revive China Society), the small organization born on that occasion, would later develop into a strong political party called Tung Meng Hui (Alliance Society). In 1911, Tung Meng Hui led a successful uprising, overthrew the Manchu regime (which had ruled China since 1644), and founded the Republic of China. Tung Meng Hui would later change its name to Kuomintang (Nationalist Party) and control China for three decades, until 1949. If, as Sun said, “Hua Qiao [overseas Chinese] are the mother of revolution,” Honolulu’s Chinatown certainly deserves to be called the cradle of modern China.

Sun and his comrades had to keep secret the 1894 meeting, and many others like it, because the Manchu regime had put a price on Sun’s head, and Chinese consuls in Hawaii maintained a close watch on his activities. There is no record to indicate that Chang Apana ever crossed paths with Sun, although the fact that Apana had cut off his queue might have sat well with the anti-Manchu revolutionary. But Apana received medals from two visiting Manchu princes in 1910, literally on the eve of the Ching dynasty’s collapse, suggesting that Apana probably had stayed above the fray of ideology. When the so-called hatchet wars broke out between Manchu royalists and the Hsing Chung Hui members in Chinatown, Hawaiian newspapers invariably branded these hatchet-wielding, knife-slashing street battles as “tong wars.” But no matter whose turf it was, Apana had to walk the most dangerous beat in Honolulu. He was a cop, pure and simple.