8

Desperadoes

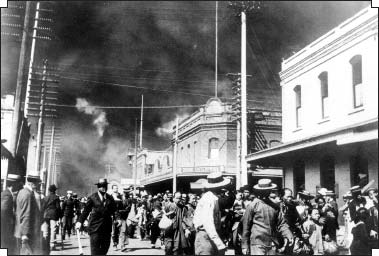

DURING THE 1900 CHINATOWN FIRE, RESIDENTS WERE EVACUATED UNDER POLICE DIRECTION (Courtesy of Hawaii State Archives)

When he goes there, he’s going to pick up those fellas, and he never miss.

—HPD Officer George Kelai, referring to Chang Apana1

A MASTER OF DISGUISE, Chang Apana shared with his fictional double, Charlie Chan, the exceptional ability to outwit opponents. Like his cinematic twin, he also showed a steely determination to hunt down the guilty. The comparison, however, cannot stretch too far. Unlike the portly detective whose body severely impedes his mobility, Apana had a physical side to his modus operandi. His thin and wiry body was the frame of a rough-and-tumble paniolo. His were the early days of law enforcement in Hawaii, when brute physical strength was more critical than fast-flying bullets.

During one raid on a Japanese gambling ring, an expert Japanese wrestler—as if out of a comic—threw Apana and another officer over his shoulder and onto the ground. Weeks later, Sheriff Chillingworth, a tall and muscular man who knew a thing or two about wrestling, tangled with another gambler who turned out to be an even more daunting opponent. According to a Pacific Commercial Advertiser article, Chillingworth tackled the Japanese, who was about as tall as he was. “The fellow at once showed that he was skilled in the art of wrestling, for the instant Chillingworth extended his hand to grasp him, the Japanese caught his wrist and turning his back toward him, made as if to throw him over his shoulder.” The article continues:

Chillingworth knows several of the tricks of the profession, and luckily escaped the throw, with the result that both went to the ground together, where each attempted to be the upper man. They struggled, both applying every muscle. Both finally got to their feet, and the scientific battle went on again. Now it was Chillingworth, now it was the Japanese. The deputy attempted to catch the bullet head of the Jap between his hand and elbow and bend it over almost to the breaking point, but so surely as Chillingworth made the attempt he was balked by a counter move at his wrist.

When Chillingworth finally subdued his opponent with an expert throw, he was immediately grabbed by a fellow officer who mistook him for the Japanese, for by this time, Chillingworth’s coat had become totally soiled in the hands-on combat.2

Apana had his fair share of physical fights. As described in the previous chapter, he was no stranger to being hurled from an upstairs window or run over by a buggy; his encounters with danger and death were hardly infrequent. According to the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, Apana had a confrontation in March 1905 with a Chinese named Lee Leon, who subsequently sued Apana “for $2,000 damages on account of assault and battery with fists, hands, and feet.” The plaintiff claimed that the officer had beaten him up so badly that he “was laid up for a month and incurred a doctor’s bill of $100, besides detention from business.”3 The cause of that fight remains unknown, but Apana’s other confrontations, often with criminal desperadoes, are well documented.

Chillingworth once assigned Apana to capture two fugitive lepers. Apprehending lepers was, in the words of John Jardine, a veteran HPD detective, “one of the most controversial duties ever given the police in Hawaii.”4 As Apana later recalled, his knees did quake a little when he got the assignment.5 Leprosy, one of the oldest known human diseases—in fact, older than the Bible—had long been the unspoken dark secret of Hawaii. Jack London incurred no small fury and animosity from the islanders in 1909 after he published stories about Hawaiian lepers. Leprosy first appeared in the islands as early as 1830. The natives called it mai pake (Chinese sickness), because they believed that a Chinese had brought the malady to Hawaii. By 1865, leprosy had become so serious a threat that the Hawaiian legislature passed an act to prevent its spread. In 1866, the year of Mark Twain’s visit, the government schooner Warwick began transporting lepers to a newly created lazaretto on an isolated peninsula on the island of Molokai. The dreaded journey was Hawaii’s Bridge of Sighs, a hopeless one-way trip. Even after Norwegian scientist Armauer Hansen identified the bacillus Mycobacterium leprae in 1868, there was still no cure for leprosy and very little knowledge of how the disease was transmitted. By the end of the 1860s, more than a thousand lepers had been sent to Molokai, where they would wait helplessly while the cursed disease slowly ate away their bodies—peeling off their skin, disfiguring their faces, and extinguishing their vision. They would die in agony, forgotten by the world.6

Dreading such a horrible fate, some lepers tried to put up resistance or evade capture by the police. The most infamous among these fugitives was a paniolo named Koolau. In 1893, immediately following the overthrow of Queen Liliuokalani, the thirty-one-year-old Koolau was helping the haole government round up known lepers on the island of Kauai. When he discovered that he had contracted the disease, he agreed to go to Molokai under the condition that his healthy wife, Piilani, could live with him on the leper colony. But at the last minute, she was held back by government officials, and Koolau leaped overboard and swam back to shore. He then fled with his wife, their young son, and a small band of lepers into the almost-inaccessible Kalalau Valley. For three years, they hid in the valley and resisted capture. Armed with a single rifle, Koolau held off the sheriff’s posses and killed several deputies. Then his child succumbed to leprosy, and the grieving couple buried him there. Two months later, Koolau died and was buried in a grave dug by his wife with a small knife. Jack London, whose 1909 story, “Koolau the Leper,” has immortalized the character, heard the tale from Bert Stolz, a young crewman working on the deck of his yacht, the Snark. Bert’s father, Louis H. Stolz, was one of the deputy sheriffs shot by Koolau on the perilous ridges of Kalalau.7

The two Japanese lepers Apana had to capture were almost as dangerous as Koolau. The Kokuma couple, who had successfully evaded the police and had put out the word that any attempt to take them would mean a fight to the death, were hiding out on Dillingham Ranch, at upland Kawaihapai.

The posse consisted of Captain Robert Parker Waipa, Apana, and two other officers. They arrived at the foot of the high slopes of Kawaihapai in the early morning. Through a thin layer of fog, they could see, about a mile up, a rambling plantation house. In order to surprise the Kokumas, the team split up and crawled through the brush of the mountainside. It had rained overnight, and the ground was muddy and slippery. Apana was first to get up there, his clothes all wet and soiled. Approaching the house with quiet steps, he surprised Mr. Kokuma coming out of the outhouse, still tying his pants as he walked. At the sight of the officer, Kokuma rushed for a rifle stashed near the front door, but Apana cut him off. The two men immediately became locked in battle. Kokuma somehow got hold of a sickle, and he started slashing and thrusting like a madman. Apana was cut several times across the arms and face. At last he knocked the sickle out of the leper’s hand and handcuffed him.

Before his teammates arrived, Apana proceeded to look for Kokuma’s wife. The fight outside had already roused her from sleep. As Apana entered the house, she, like her husband, made a run for a rifle leaning against a wall. As she dashed by him, Apana grabbed her flowing hair and pulled her back. Enraged, she turned around and attacked him like a wildcat. The fight, as Apana later declared, was “more terrible than with her husband.” When his fellow officers at last came to his aid, Apana was about to “sink with exhaustion.” The two lepers, according to a police report, were arrested, taken to the police station, and later deported to Molokai.8

Fortunately, unlike Koolau, Apana himself did not contract leprosy, despite such close encounters. But the Kokuma confrontation left a permanent imprint on him. Photos from his later years clearly show a scar above his right eyebrow, a souvenir from the sickle attack.

Apana’s bravado and bravery would soon win the confidence of his superiors. At some point, he was promoted from street officer to detective, despite the fact that he had no formal education and could read no English or Chinese. Becoming a detective sealed Apana’s fame in the annals of history.