11

Lampoon

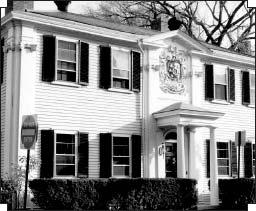

THE SIGNET HOUSE, CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS (Photo by Ian Graham, courtesy of the Signet Society)

I park my car in Harvard Yard.

—Anonymous

AT THE DAWN of the twentieth century, Harvard University was in the waning days of what George Santayana termed “The Genteel Tradition.” The unprecedented forty-year reign of President Charles W. Eliot would come to an end in 1909, six years after Earl Biggers graduated from Warren High School and matriculated at Harvard. In 1910, William James, father of American psychology and pragmatism, would die. Santayana himself, who had arrived on a horse and buggy as an immigrant from Spain, would resign from his professorial post at Harvard in 1912 and leave the country for good.

Popular culture, eroding the gap between the high-brow and the low-brow, also made inroads into the ivory tower alongside the Charles River. Biggers, a youngster from the cornfields of Ohio—short, round, dark, bright-eyed, with a friendly manner—was perhaps the best representative of such a change of tide in American culture. The freshman Biggers showed little passion for the classics. In a few years, the fifty-volume Harvard Classics, edited by Charles Eliot, would grace the living rooms of American households aspiring to the upper class. Eschewing the likes of Dr. Eliot’s Five-Foot Shelf, Biggers preferred Rudyard Kipling and Richard Harding Davis, and he considered Franklin P. Adams a better storyteller than Oliver Goldsmith. A professor who heard his announced preferences in class bemoaned, “Oh, Biggers, Biggers, why will you be so contemporary?!”1

On evenings when refined Harvard classmen were reciting Keats and Shelley to one another over shots of brandy and sherry, they would jokingly urge Biggers to leave the room.2 When T. S. Eliot, who entered Harvard during Biggers’s senior year, was contemplating the composition of “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” in which the speaker is too nervous to approach women at a party, Biggers had an entirely different literary treatment of the same topic. In Eliot’s poem, now a classic of high modernism, the “I,” balding and thin-limbed, lingers forever over a series of self-doubting questions. Drafts of Eliot’s poem were subtitled “Prufrock among the Women.” Like Biggers, who might have taken the name “Charlie Chan” from a Chinese-laundry sign seen in his younger years, Eliot was said to have borrowed “Prufrock” from the name of a furniture company called Prufrock-Littau, near his birthplace in St. Louis. But Eliot added a mysterious initial “J” to the fictional name “Alfred Prufrock,” just to make it sound more aristocratic. By contrast, Biggers’s winning entry in the Harvard Advocate’s contest for the best “pick-up” story was sold to a popular magazine for $25.3 The future creator of Charlie Chan and the future Nobel laureate were obviously traveling on different express trains with not the slightest chance for a collision.

Even though his unabashed populist taste clashed with the literary pretensions of his classmates, Biggers joined several Harvard societies, including the prestigious Signet Club and the Lampoon. The Signet, founded in 1870, is perhaps the most elitist literary society on campus. Dedicated to the production of literary work (and later expanded to include music), the Signet boasts members who have defined twentieth-century American literature: T. S. Eliot, Robert Frost, James Agee, Wallace Stevens, Norman Mailer, John Updike, and John Ashbery, to name just a few. The Lampoon is decidedly a more mixed bag—its notable alumni include William Randolph Hearst, George Santayana, Robert Benchley, John Reed, Conan O’Brien, and numerous writers and producers of television comedies and feature films that have defined American humor: The Simpsons, Saturday Night Live, Seinfeld, Futurama, and The Office. The odd mixture in these clubs of future movers and shakers—high and low, elitist and populist—speaks volumes to the reach of the rising popular culture, and to the fact that what Thorstein Veblen called the “leisure” class was losing its monopoly over American culture.

I will never forget my first and only visit to the Signet Club. It was in the spring of 2000, my first year as an assistant professor at Harvard. One of my students, a Signet member, had invited me to lunch at the clubhouse on Dunster Street. Entering this charming yellow house tucked away on the fringe of Harvard Square, I noticed an ornate coat of arms, the signet ring, hanging above the front door, where I was greeted by my student and her fellow club members—all undergrads except for one elderly gentleman, who was standing in the far corner of the reception room. When I inquired about the many dried roses hanging on the walls, my student explained that it is the tradition of the society that, upon induction, each new member receives a red rose. It is to be kept, dried, and returned to the society upon publication of the member’s first substantial literary work. Particularly noteworthy to me was T. S. Eliot’s rose, enshrined with his original acceptance letter.

My student, a six-foot blonde whose elegant manners recalled, say, a charming heroine from a Henry James novel, continued to give me the inside scoop about Signet treasures, such as the famous pipe once owned by William Faulkner that allegedly had been used by some adventurous undergrads to smoke pot; and the handwritten poem by Santayana in the ladies’ room, to which I would, regrettably, have no access.

It was right at this point that the elderly, gray-haired gentleman approached me and introduced himself: “How do you do? S—P—, ’57.” The diplomat part of me quickly shook his extended hand, and I was able to reply, “Hi, I’m Yunte Huang. Nice to meet you.” But part of me was rendered speechless. Other than the formulaic, “Nice to meet you,” applicable almost anywhere, I had no answer to his self-introduction, “S—P—, ’57.” For me to say, “Yunte Huang, Peking University, ’87,” would have seemed to challenge the niceties of the exchange. His “’57” meant that he was a member of the class of 1957, of no other university than Harvard. What’s absent in the information should be taken for granted—an implied context of parlor talk, hidden as a secret badge but obvious as daylight. Making this succinct self-introduction, either he assumed I was a member of that community who would be able to reply without ambiguity—“Yunte Huang, ’87”—or he was putting me on the spot by asserting his insider status.

Between our introductions, a gulf had opened, a chasm so wide that neither of us seemed able to reach over and compare notes from our life experiences. He was, as I learned from our brief chat in the room decorated with dried roses, a retired English professor from a Boston-area college. He had been educated at Harvard, both as an undergrad and as a graduate student, and had been a member of the Signet since his junior year. By contrast, I suspect I must have seemed to him like a social upstart, getting to where I was not by entitlement but by luck—or, even worse, by the magic wand of equal opportunity.

He could hardly have known that I grew up in a rural village in southeastern China, and even though I went to China’s foremost university, that would not, in many American eyes, really count. After I came to the United States, the cycle seemed to repeat, as I started almost from scratch in Tuscaloosa. I am one of those against whom Henry James, the old gentleman’s favorite author, once warned in his 1905 Bryn Mawr College commencement speech—those immigrants who came to this country, sat up all night, worked mindlessly, and then played to their hearts’ content with the English language. The fact that I was assigning my Harvard undergraduates to read Gertrude Stein—“a horrible prose writer,” as the old gentleman sniffed—was perhaps proof enough of my poor taste and the sad state of Harvard education. As for other authors whose work I taught in my classes, such as Maxine Hong Kingston, Theresa Cha, and Leslie Marmon Silko, he had either never heard of them or would not, as he remarked with polite nonchalance, “consider them as worthy of studying.”

James’s friend, Henry Adams, whose classic autobiography reveals, among other things, how a Harvard education failed to prepare him for new problems in American culture, put his finger on the issue when he described a scene of symbolic confrontation between immigrant upstarts and people of entitlement like himself. Returning in 1868 from Britain, where he had gone to avoid fighting in the Civil War, Adams, upon witnessing the influx of immigrants at the docks in New York City, described his feelings this way:

One could divine pretty nearly where the force lay, since the last ten years had given to the great mechanical energies—coal, iron, steam—a distinct superiority in power over the old industrial elements—agriculture, handwork, and learning—but the result of this revolution on a survivor from the fifties resembled the action of the earthworm; he twisted about, in vain, to recover his starting-point; he could no longer see his own trail; he had become an estray; a flotsam or jetsam of wreckage; a belated reveller, or a scholar-gipsy like Matthew Arnold’s. His world was dead. Not a Polish Jew fresh from Warsaw or Cracow—not a furtive Yacoob or Ysaac still reeking of the Ghetto, snarling a weird Yiddish to the officers of the customs—but had a keener instinct, an intenser energy, and a freer hand than he—American of Americans, with Heaven knew how many Puritans and Patriots behind him, and an education that had cost a civil war.4

Just as James was alarmed by the mongrel crowds of dagos, Danes, Irish, and the like, Adams felt defeated by the hordes of Yiddish-sputtering Eastern European Jews who seemed much more energetic and instinctual than he, “American of Americans,” who surely ought to be entitled to the leadership and hence championship in the game of life.

On that particular day at the Signet clubhouse, I felt neither humiliated nor proud in front of that old gentleman, “S—P—, ’57.” I was actually thinking about Earl Biggers, an author I had then just started researching. I wondered how Biggers, a so-called rube from Ohio, felt when he first stepped in the club that eventually elected him an honorary member in 1908, a year after his graduation. Biggers, a small-town midwesterner whose parents had had to borrow money to send him to college, had to climb the social ladder through sweat and toil, unlike the two blue-blooded Henrys.

The lunch was delicious, like most Harvard meals, until they get repetitious and tiresome. Garden salad, grilled salmon, scented rice, and broccoli that was always a bit overcooked. And the conversations continued to be polite and jolly, like well-polished English prose.