Chapter Eight

Bridge of Dreams

HONEY CREEK BEGINS about five miles north of our place and runs due south until it meets the Black Fork of the Mohican River. The watershed of about one hundred square miles includes four tributaries—Clear Fork, Black Fork, Jerome Fork, and Muddy Fork—flowing from the north to join the Lake Fork, which becomes the major part of the river. The Mohican in turn joins the Kokosing River to become the Walhonding, itself a major tributary of the Muskingum, which runs south from Coshocton to Zanesville, then southeast toward Marietta where it empties into the Ohio River. The Ohio flows southwestward until it joins the Mississippi at the southern tip of Illinois.

The village of Loudonville calls itself the “Canoeing Capital of Ohio” because of its location on the Mohican. According to local journalist and naturalist Irv Oslin, a man named Dick Frye established a canoe livery in 1961 and transformed Loudonville into a resort area. In the 1970s and ’80s, however, there were few people paddling the river or camping in the park. Today the stretch of the Clear Fork that flows parallel to Ohio State Route 3 southeast of the village is crowded with motels, camping facilities, canoe liveries, carnival rides, water slides, and restaurants. Still, at Frye’s Landing the river becomes less civilized. Greenville, once a commercial center and stop on the Walhonding Valley Railroad, now boasts only a few houses and a church. Downstream, the river meanders past steep, forested hills and farms. After Brinkhaven Road Bridge, at a bend called Alum Rock, the canoeist sees stunning rocky outcroppings some three hundred feet high.

The most natural section of the Mohican, eighteen miles of the Lake Fork from Brinkhaven to the Mohawk Dam, traverses a gradually widening valley densely forested and inhabited by much wildlife. Canoeists and hikers can sight bald eagles, belted kingfishers, cedar waxwings, great blue herons, green herons, and wood ducks. Alert observers spot beaver, muskrats, river otters, and white-tailed deer. Ospreys perch in high branches waiting for the fish that swim to the surface in the wake of passing canoes. Brinkhaven was a thriving community until disasters of biblical proportion caused its people to leave: the great flood of 1913 washed away its woolen mill, and a fire in 1951 destroyed the gristmill. Another settlement on this fork, Cavallo, once a commercial stop on the canal route, became a ghost town when the railroad rendered the canals obsolete by 1896. Brinkhaven Dam produces a churning turbulence, and drownings were not infrequent (as many as eight people in a single summer) until a section was carved out with jackhammers to make the passage safer.

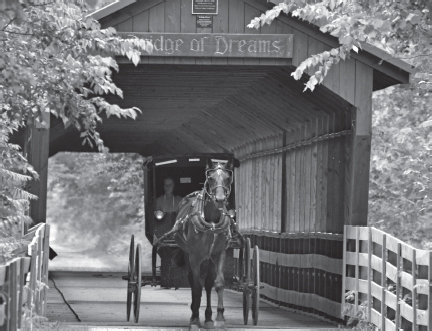

Near Brinkhaven, in Knox County, a covered bridge said to be the second longest in the state (370 feet) and the third longest in the country spans the Mohican River. Covered bridges are nothing new in Ohio, which contains 142 of them, the second largest number in the country after Pennsylvania’s 219. Many of Ohio’s covered bridges are modern, but most were first constructed in the nineteenth century and have since been remodeled, updated, or repaired. A former railroad trestle constructed in the 1920s, the bridge near Brinkhaven joins sections of the Mohican Valley Trail, built on the abandoned right-of-way belonging to the old Pennsylvania Railroad. Closed to motorized traffic, it is used by hikers, cyclists, and Amish buggies. When local people developed a plan to cover the bridge, skeptics claimed they were “dreaming.” The planners proved that they could make their dream come true by raising the ninety thousand dollars needed for the project. When the bridge was dedicated in 1999, they named it the “Bridge of Dreams.”

The Clear Fork of the Mohican River runs thirty-six miles past varied landscapes, including a former gold prospecting camp. The bottom is rock, gravel, and sand with natural riffles and pools, which make it one of the highest-quality fishing streams in the state. On its banks, Newville became a ghost town when the B&O Railroad carried its business away by building tracks through Butler and Perrysville. Another abandoned community, Helltown—named for the German word for “clear” and home to both pioneers and Native Americans—was abandoned in 1782 when the Delaware moved to Green-town after learning of the massacre at Gnadenhutten of native people converted to the Moravian faith. One favorite part of this tributary is the nearly five-mile stretch called Clear Fork Gorge where hills covered with mature conifers and hardwoods rise three hundred feet from a valley one thousand feet wide. Placed on the National Registry of Natural Landmarks by the National Park Service, the gorge can be viewed from below in a canoe or above from a ridge where the forested slope plummets steeply to the stream; on the other side, a succession of hills rises green and blue into the distance. This part of the forest is off-limits to hiking, so there are no footpaths descending the steep hillside.

If quiet is the place where one can listen fifteen minutes and not hear a human-created sound, then there are quiet places on the Mohican River and in the surrounding forest. One trail offering varied terrain and forest ecosystems follows the north side of the river from the state park headquarters and passes near the Clear Fork Gorge State Nature Preserve before terminating at Pleasant Hill Dam. One of the more challenging hiking trails—and consequently less traveled—begins at the fire tower and traverses four miles through part of the state forest to the modern covered bridge at State Route 97. From there to Charles Mill Lake, the trail follows the river through the Mohican State Park and reveals spectacular vistas, large trees, rocky outcroppings, and two waterfalls (Big and Little Lyons Falls) but also many more hikers and picnickers, as this is most visitors’ favorite part. While the park boasts only about eight miles of well-used trails, the forest contains about fifty miles of less-visited paths dedicated to snowmobiling and horseback riding but which hikers can also use to take them into back country with varied forest ecologies, cliffs and gorges only slightly less spectacular than those in the park, and openings that reveal rolling countryside and farmland. Along parts of the trail, one can imagine the awe as well as fear that pioneers must have felt when riding or walking through those deep woods. One of the longer bridle trails passes an old church now boarded up and standing near the tiny Sand Ridge Cemetery, established in 1803 and containing many weathered headstones with indecipherable names and dates. Veteran back country hikers who know the forest well have identified evidence of native and pioneer dwellings. Local naturalists call it “a little piece of Canada” because glaciers, pushing the soil southward, stopped at the Mohican hills, where observers now can spot cerulean warblers and other songbirds usually seen farther north.

On the Black Fork of the Mohican, Charles Mill Lake—1,350 acres in size, with thirty-four miles of shoreline—appears natural but is not. Constructed in 1938, the Charles Mill Dam, one of fourteen built along the Muskingum Watershed by the US Army Corps of Engineers, turned three rather deep natural lakes (about fifty to one hundred feet) into one large body of water only about eight feet in depth. Nevertheless, with its resident populations of eagles, ospreys, egrets, and herons and visited by migrating sandhill cranes and white pelicans, the lake looks beautiful in any season.

Natural history is omnipresent in this area, although few people know it. The greatest “natural” disaster in Ohio history was the flood of 1913, caused by four days of torrential rain over land that had been robbed of its forest cover throughout the nineteenth century, which left about 450 people dead and two hundred fifty thousand homeless. Downtown Dayton, the hardest hit municipality, lay covered by twenty feet of water. In response, the Ohio General Assembly created four flood-control districts, of which the Muskingum Watershed Conservancy District, organized in 1933, served eastern Ohio—about 20 percent of the state’s total area, or nearly eight thousand square miles. The districts are governed by boards of directors chosen by judges in the counties included in the region, but day-to-day operations are carried out by seven board-appointed “executives” who are mostly not known by the people living in the district. As of this writing, the chief of conservation, whose term began in 2018, is a person who worked in the oil and gas industry for sixteen years.

The entire Mohican Complex includes nine thousand acres of forest and parkland consisting of the Mohican State Park and Forest, Pleasant Hill Lake State Park, and Malabar Farm State Park, with spectacular geological formations, mature forests, prairie tracts, and waterfalls such as Hemlock and Big Lyons Falls. Conservation easements preserved 579 acres in Richland County alone. A new trail, opened in 2015, links the Richland B&O Trail and others to the Mohican, fortunately off-limits to all-terrain vehicles and dirt bikes.

The Mohican State Forest, located in Richland and Ashland Counties, consists of 4,525 acres of abused and abandoned farmland reseeded and replanted by the Civilian Conservation Corps. The restored forest contains some of the most valuable timber in the state, a fact not lost on wood and paper companies who try to convince sympathetic legislators to allow them to log in public land under the rubric of “management” and even in the Shrine Memorial Forest Park set aside to honor fallen veterans. Timber company representatives even describe clear-cutting disingenuously as “imitation of a natural process,” since lightning sometimes clears out sections of forests, but their reasoning overlooks the fact that natural processes are not planned. Over the last twenty-five years, I have participated in a number of demonstrations at the forest shrine or the Sand Ridge Cemetery to save parts of the Mohican from logging, mostly friendly gatherings where Forest Service officials and State Highway Patrolmen mingled with demonstrators. Now this land is under threat not only from logging and mining but more recently from oil and gas exploration and horizontal hydraulic fracturing.

The Department of Forestry (DOF) unveiled a new plan in 2017 to log forty acres of mature woods because, it claims, the white and red pines planted in the 1940s are not indigenous to the area; although the land had been twice thinned of pines, they claim that new logging would allow the more valuable hardwoods to grow back. Yet areas that were clear-cut in 2008 with the purpose of restoring indigenous ecology have not grown back in hardwoods but in sassafras and bush honeysuckle, invasive species that even the DOF, currently headed by a former timber company “resource forester,” admits it does not have staff enough to remove. The state allows periods of public commentary, and DOF officials hold public hearings, but often in rooms too small to accommodate all the people who attend and sometimes employing strategies such as not allowing public questioning—they claim, because such opportunities can become “confrontational.”

We need a new dream for this watershed and its entire eco-system—a dream that includes preservation of old growth forests, diversified ecosystems, and love of the land even if it still bears its human-created scars.