The ultimate powder harvesting tool: A Bell 212 and tracks in the Bobbie Burns. TOPHER DONAHUE.

4

A single footprint is a big impact – if you happen to be the flower that gets stepped on.

— Hans Gmoser

Each gust of wind pushes the suspension bridge back and forth beneath my feet. My boots are planted firmly on solid wood planks, my hands are on steel cables and I’m attached to a cable with a climbing harness. But even knowing I’m anchored like a sail in a hurricane, I’m acutely aware of the exposure below and adjust my balance intently with each movement of the span. The experience is more a Lord of the Rings than a Bay Bridge kind of affair; a perfect Hollywood set for a battle between wizards or maybe a causeway for elves. It’s a hundred feet to the solid rock on the other side and almost the same to go back where I came from. Beneath me a rock face sweeps into the deep valley a vertical kilometre below, and in the distance the forested valleys and prickly peaks of the Columbias stretch past the horizon. To my left, a blinding white glacier catches my eye. I stop, balanced between two planks with nothing but air between my feet and take in the view from this unique perch.

In 30 years of mountain adventures from the Himalaya to the Andes, I have never been in such a place. Looking past my feet, I see the multicoloured layers of rock in the folded earth form a quilt of bizarre patterns where the glacier ends. I turn my head to look over my shoulder towards the spire we just climbed on our traverse of Nimbus Tower. It is far more slender than it appeared while we were climbing on it, the summit a razor point against the deep blue sky. Looking up from the swaying bridge is dizzying, and clouds move behind the spire, complicating my mind’s attempts to compensate for my unstable footing. Another gust of wind brings my attention quickly back to the airy path in front of me. I am thankful for the climbing harness and tether attaching me to a cable running above the bridge. Nothing short of an errant helicopter could actually send me tumbling from the exposed position, but it sure feels tenuous. Step by careful step I walk closer to the other end of the bridge. A question runs through my mind, “And this is heli-hiking?”

The bridge is made of cables attached to a spider web of anchors and expansion bolts drilled into the rock. It is part of a trail of rungs and safety cables that make the ascent possible for anyone who can climb a ladder. The exposed passage is called a via ferrata, a European invention that has yet to catch on in North America, although a few exist here, including the popular cable route to the summit of Yosemite’s Half Dome. Via ferrata is Italian for “iron road,” and in the Alps they are as common as parking lots in the Rockies. The online encyclopedia Wikipedia explains their purpose as allowing “otherwise isolated routes to be joined to create longer routes, which are accessible to people with a wide range of climbing abilities. Walkers and climbers can follow via ferratas without needing to use their own ropes and belays, and without the risks associated with unprotected scrambling and climbing.”

Via ferratas open access to the kind of terrain usually reserved for technical climbers, and in the rugged terrain of the Columbia Mountains they are a practical next step to connect valleys, bypass glaciers, surmount cliff bands and reach summits that otherwise would be unappealing to climb with traditional means and impossible to reach for hikers. The first two via ferratas in the Columbias were built by the CMH Bobbie Burns guides, and their thrills are just beginning to be experienced by hikers. The first, on a lonely ridge below Mt. Syphax, was completed in 2005. It connects a traditional climb from a glacier to the summit with an exciting knife-edge ridge that only expert climbers would dare traverse without the metal rungs and safety cables – and even for experts, some sections of the rock are too fractured to be a worthwhile rock-climbing objective. The second is the Nimbus Tower traverse, finished in 2007, and it includes the sphincter-tightening 60-metre suspension bridge.

Like heli-skiing in the early days, the project is an isolated labour of love by the guides. No one is telling them what to do or how to do it. It is not a marketing scheme or a brand statement – it is a way of taking people into a part of the mountains they wouldn’t get to otherwise. Just like the Bugaboos in the sixties, the Bobbie Burns in the new millennium is redefining the nature of mountain sport. Hikers who finish the via ferratas experience something they’ve never heard of, seen photos of, or imagined. With the position and exposure of a technical climb but the ease of climbing a ladder, in an environment with the remoteness of a National Geographic expedition but the ease of access of a long weekend away from home, the via ferratas of the Columbias are destined to inspire wide eyes, future stories and controversy.

The ultimate powder harvesting tool: A Bell 212 and tracks in the Bobbie Burns. TOPHER DONAHUE.

For many North American outdoor enthusiasts, the idea of drilling metal ladders into the rock, festooning a stone spire with cables and creating a pathway out of vertical rock is anathema. If anyone tried to install a via ferrata in a national park anywhere on the continent, there would be outrage. Interestingly, the ladder up Yosemite’s Half Dome was installed first by a blacksmith and then rebuilt by none other than the Sierra Club, one of the world’s most respected environmental organizations. The use of our wilderness hangs on a pendulum swinging between access and conservation, and the future use of wilderness will require careful consideration of both elements.

The via ferratas of the Columbias are not in national parks and are located in the heart of a mountain range where few, if any, other hikers, backpackers, backcountry skiers or climbers will ever see them. They allow access to peaks made of such loose rock that even the most adventurous climbers would choose another route. If placed with consideration, a number of breathtaking via ferratas could be installed in the Columbias that would affect the aesthetic of the range not at all. Just like huts, trails, roads, climbing anchors and other human installations, if via ferratas are placed with abandon, they will be little more than permanent litter on our beloved mountains, but if placed with care they will only enhance the wilderness experience.

While heli-skiing is the most famous aspect of the legacy of Hans Gmoser, the summer program more closely fits his original vision of using the helicopter as a means to extend alpine tours into the most remote terrain western Canada has to offer. During the winter, the helicopter is used hourly or more as a ski lift for shuttling skiers into as many powder turns as possible over the course of a day. In the summer, the machine is merely a way of getting out there – albeit an incredibly exciting, scenic and versatile way. Often the helicopter will be used once in the morning to access the high cirques above the thick bush, pesky mosquitoes, monster bears and even bigger and more irritable moose. The hikers and climbers are left in silence for the day and their chosen adventure. When they have explored everything time, weather and curiosity allows, or hiked to a state of contented exhaustion, the guide calls in the helicopter for a quick return to the lodge.

One hiker commented, “That’s the magic of it – one minute you’re in the alpine world and the next you’re sitting on the deck with a cocktail in your hand.”

The potential of the jet-powered equalizer is still being realized, and recently the term heli-hiking has become a bit of a misnomer. The summer use of the helicopter and the remote lodges ranges from world-class rock climbing on one extreme to short strolls through a flower garden on the other, or as one hiker explained, “I just found a spot I liked, sat down, and drew pictures in my tablet while the others went hiking.”

An artist finding a view to get the creative juices flowing and a hard-core climber finding a first ascent to get the endorphins flowing are at opposite ends of the spectrum of mountain pursuits, but both accomplish the same thing: full immersion in a wild world and an experience giving the individual a time away from the hectic and complicated world of jobs, family needs, automobiles, deadlines and stress. One hiker summed it up: “Heli-hiking, heli-eating, heli-hot-tubbing; it’s a heli of a good time. It’s a very sad day to depart from this majestic mountain lodge and return to the reality of the everyday world.”

By using technology, information and experience, more and more people are finding the rewards of this kind of unmeasured time in an alpine environment where, if they were left naked and alone, death would find them in a matter of hours or days. It is a world where we are not at the top of the food chain, a world where we are forced to be humble and respectful, and a world where the ephemeral value of the wilderness is clear.

For a time, only the hardiest adventurers explored the wildest mountains of North America; then trains, highways, trails, logging roads and shared information allowed fit adventurers to achieve the lofty heights and to walk across the lush tundra ecosystem and return home with a greater respect for the natural world. More recently, roads have been bulldozed into some of the most spectacular alpine terrain in North America. Mt. Evans and Pikes Peak in Colorado are particularly dramatic examples, with roads slicing through tundra to reach 4000-metre summits. These roads invite questions: do the roads take people into the wilderness, or does the wilderness retreat from the road, making the two utterly irreconcilable? Can a person gain respect for the natural world by seeing it through the window of a car? According to the Hans Gmoser school of wilderness, the answer is no, the mountains must be touched, smelled, felt and even tasted, as well as seen. Getting out of the car and off the road is necessary to experience and learn from wilderness. The obvious question, then, which surely enters the reader’s mind even before finishing this sentence, is: can people experience the natural world by flying a helicopter into it?

According to the Hans Gmoser school of thought, the answer is yes, as long as they get out of the machine. Just a sightseeing tour, spent peering from the window of a plane or helicopter, is little better than watching a video of the mountains rolling past – albeit in a thrilling amusement park ride. During the winter, the hectic pace of heli-skiing’s powder mania and the trend of chasing vertical footage distracted people’s attention from the natural world and took heli-skiing further from Hans’s original vision of sharing the complete mountain experience. Ironically, it was the pressure of business that inspired a return to the more meditative touring element of heli-sport.

Hans became indebted to bankers as his business grew, and increasing the number of guests was essential to the project’s survival. Winter was lucrative, but just because the snow melted didn’t mean the bills stopped coming. Margaret Bezzola, the original house-manager of the Bobbie Burns lodge, remembers: “Hans would never have enough money to pay for (jet fuel) for the winter, so every summer he would have to take out a loan to pay for the next season’s fuel.” There were times when the cook only put one tea bag in a huge pot of water to save the pennies needed to flavour the pot properly. Kiwi remembers the atmosphere of the difficult times. “Investors were pulling their hair out that the only way the business would keep going was because the bankers liked Hans.”

Back in civilization, heli-skiing is a business like any other, and Hans and his team had a number of near disasters in the bankers’ world as well as in the mountain world. First, it was the cost of building the lodges, each one putting the business on the edge of bankruptcy. Next, it was finding something to do when the deep snows melted. Like the ptarmigan, the alpine bird that every spring replaces a coat of thick white winter feathers with dark ones to blend with the summer tundra, the project needed to change dramatically with the seasons.

In the Hans Gmoser school, participation is essential to experiencing and respecting the natural world. Skiing was a natural reason to use a helicopter to increase access for people who wouldn’t go there otherwise, but what to do in the summer? CMH already had lodges and staff, so all that was lacking was the right activity to get people out there. As usual, there was no clear, grand vision, so in the beginning the guides tried everything they could think of. Early attempts to create a summer program ranged from the nearly disastrous to the hilarious. Summer offerings included horseback riding, canoeing in Bugaboo Creek and even tennis on a court installed at the Bugaboo lodge. Much fun was had and millions of mosquitoes enjoyed litres of fresh blood, but nothing really caught on.

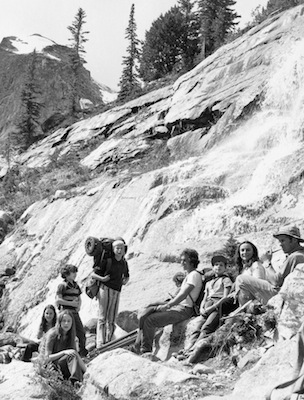

A group of young explorers nearing treeline below the Bugaboo Spires. CMH ARCHIVES.

One of the more promising summer programs was the Young Explorers Club, an impromptu camp for teenagers led by the ski guides in the mountains around the Bugaboo lodge. However, the ski guides were far from expert summer camp instructors. Rudi Krannebitter once went ahead to prepare camp and set up a group of tents – in the wrong valley. Canoeing in Bugaboo Creek was fun, but as Krannebitter put it, “Sepp (Renner) and Rudi (Gertsch) didn’t know what end of the canoe was front. They weren’t water people but they had to pretend they knew what they were doing in front of a group of teenagers.”

Recently, Renner met a middle-aged man who told him, “I know you, we blew up some outhouses together.” At first, Sepp was incredulous, but then he realized the man was a former Young Explorer. On one of the camping trips, the Explorers found a box of dynamite and blasting caps in an old mining claim, and while the guides were not skilled at boating, they knew how to blow things up from their work building the lodges and doing avalanche control. The campers wired up the dynamite and proceeded to pulverize everything they could find, including the outhouse of the mining claim. While this was not the solution for summer solvency for CMH, it left some lasting memories for a number of Canadian teenagers. Renner laughs with the memory: “Those kids loved it, but imagine when they went home and their parents asked them what they did at camp. ‘We learned to blow up outhouses.’”

Explosives were not a standard part of the syllabus, but no two camps were ever the same. The two-week programs involved backpacking, canoeing and mountaineering in wilderness so remote the kids were forced to become woodsmen and find comfort in the rugged high country.

A particularly memorable adventure began with Hans and Sepp taking a group canoeing on the Spillimacheen River. Hans claimed to know the best put-in, and when the group pulled up to the edge of the river, Renner looked out over the water and said, “Those are some pretty big waves. Are you sure this is it?”

Hans was confident, as usual, and simply said, “This is it.”

They got everyone organized and cast off down the river. In no time, they ran into much bigger water than they expected. Renner tells the story with wide eyes. “We went around a corner and all I could see were haystacks of water! All six canoes flipped! We swam to shore, did a head count, and one kid was missing. We ran around in a panic but found the girl hanging from an avalanche alder at the edge of the river.”

They lost two of the canoes, and Renner “gave Hans hell for that one.”

“It was a hell of a good program,” says Renner. “Nobody does these trips anymore. It’s too bad. There is too much risk. We’re turning into a nation of wimps because we can’t do anything risky anymore.”

Using helicopters to access the wilderness in the summertime never even crossed the guides’ minds. They were skiers, and in their minds, using helicopters to reach the heart of the mountain experience was the pinnacle of elitist pursuits for skiers and skiers alone. It required athletic prowess to steer long and unwieldy skis through the deep snow, and a deep pocketbook to match. Heli-skiing gave the aficionado the cachet of golfing St. Andrews along with the physical superiority of an Ironman finisher. Heli-sport was for the fit, the young and the bold – or so everyone thought.

Over the years, old ladies matched the young and cocky skiers for metres skied in a week, beginners learned to ski deep in the Columbias, and slowly people realized the true power of the helicopter was, quite simply, access. It is still expensive and, with rising energy costs, is becoming even more so. The days when using a helicopter to play in the mountains conferred automatic elite status are long gone. The game has gone full circle, and Hans’s original goal of using the helicopter to show more people the rewards and lessons of the mountains has been realized, with skiing only one aspect of it.

One man had a vision to use the helicopter as a tool to bring tour groups of retirees into the mountains. In 1925 Arthur Tauck began leading escorted travel tours in New England. He passed on his business to his son, Arthur Tauck Jr., who saw the potential in changing the flavour of adventure travel from one of hardship to one of comfort. By removing the logistics from the minds of the travellers and teaming up with hotels, restaurants, transportation services and resorts, he changed the world of tourism. In the fifties, Tauck Jr. introduced the world to tour packages combining air and bus travel to visit America’s national parks while the rest of the tourism industry was still using trains. His business flourished, and during a holiday to the Bugaboos to try the exotic sport of heli-skiing, Tauck saw an ever more diverse method of showing people the world.

He called Hans immediately, but Hans was still wrapped up in the illusion of the elitism of heli-skiing. According to Hans, after Tauck’s original phone call, he forgot about the offer entirely. Luckily, Tauck was convinced of his idea, and after Hans failed to return his call, he tried again. This time he explained his vision more succinctly: “Look, Hans, all you have to do is take people into the mountains with the helicopter and let them walk around for a while, and then bring them back to the lodge.”

According to Hans, “It was like a light bulb went off in my head.”

Discovering the sublime world of tundra on Grizzly Ridge between the Bugaboos and the Bobbie Burns. BRUNO ENGLER.

The next year, in 1978, Tauck included a stop at the Cariboos lodge in his Canadian tour. Soon the Cariboos were booked with Tauck’s guests and the Bugaboos started including the new activity, called heli-hiking, in their program. Thousands of older travellers have now seen the most remote flower gardens, sparkling tarns, age-old glaciers, pumping waterfalls and splendid isolation of the Columbias during a Tauck heli-hiking tour. Soon, individuals not involved in a Tauck tour were also booking heli-hiking trips, often with two or three generations enjoying an alpine adventure together.

Heli-skiing captured the imagination of the world by representing the speed, the perception of danger, flying snow and the agility and coordination of the skiers. From cigarette and beer ads to ski films, clothing commercials and tourism promotions, heli-skiing had the instant appeal that caught the attention of the world, and from Hollywood to Munich it became the stuff of film producers’ and marketers’ dreams. Summer heli-sport, on the other hand, is a much more subtle experience and is possible for anyone with a big enough bank account.

To understand the experience for hikers, imagine the waterfalls of Yosemite or Switzerland. Instead of flowing from a forest perched on the edge of a cliff, the waterfalls burst from the very guts of glaciers perched on dizzying precipices. And instead of standing in a smoggy valley with another 20,000 people every day, it is just you and a maximum of 44 hikers split into smaller groups in an area the size of many large national parks. The Cariboos tenure, with 1073 square kilometres, is one square kilometre bigger than Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park. The Adamants encompass 1498 square kilometres, over 200 square kilometres bigger than Wyoming’s Grand Teton National Park. The Monashees tenure is about 150 square kilometres smaller than the entire Hawaiian island of Maui, and the Bobbie Burns, one of the smallest of the CMH heli-hiking areas, is the twice the size of France’s Vanoise National Park near Mont Blanc. The best photographer or film producer in the world cannot capture the feeling of being the only human beings in such vast and spectacular areas.

Imagine the most stunning valleys in the Alps or California’s Sierra Nevada, but instead of walking along a dusty trail used by hundreds of people each day, you follow game trails made by goats, bear, caribou, moose and wolves – humans are the minority species on these trails.

Imagine the wildflowers at the peak of the season in the Tetons or Colorado’s San Juans, but multiply their numbers by the difference in annual precipitation: the Tetons average 40 centimetres of precipitation annually, while Mt. Revelstoke, a peak in the geographic centre of the heli-hiking areas, receives 127 centimetres of precipitation, three times the Tetons quota. Add long summer days of the 50-degree latitude and the growing season is a bonanza of photosynthesis for all things green and blossoming. The wildflowers and tundra in the Columbias boggle the mind. Bushes as tall as a man are draped with colour, while underfoot a carpet of life grows so thick and vivacious as to support the passing of human and animal feet, then simply bounce back to its original healthy state.

Imagine spending a day trekking through a series of glacier-carved cirques, the glaciers sitting at the top of the valleys, still immense in their retreat but mere snowdrifts compared to the mighty ice monsters that carved the mountains. The glaciers feed rivers and streams that empty into turquoise-coloured tarns sitting at the end of the moraines – the piles of rubble left by the bulldozer action of the glaciers when they began to recede after their last period of growth. It’s a glimpse into the natural machinery that shapes our world. The glaciers churn the stone into dirt, which mixes with rain and decaying plants to form rich soil where flowers can grow. Birds bring seeds from the forests, spreading vivid colours slowly across the once lifeless moraines left as the ice recedes. The caribou move through seeking nourishment in the lush flora, and the wolves follow. Bears eat everything and seek places with an abundance of life, finding the Columbias suit them just fine.

In the tourist centres of public lands in North America, the beauty of these processes is often guarded by heavily built trails and paved lookouts, signposted into lifeless facts. When you’re left in the middle of it, without a sign of human passage anywhere, the picture becomes clear in a way no tour guide could ever describe. It is an intuitive understanding, independent of statistics or names of flowers and ages of the rock, that makes all of our endeavours, struggles and interactions with the world somehow as clear as a fresh gloss of ice across a limpid alpine pond.

This is where Hans Gmoser told his clients not to throw orange peels because they don’t biodegrade as quickly as other fruit and vegetable waste. This is where the strong are brought to tears by beauty, and young men find the confidence to propose marriage. The helicopter allows an experience without the athletic prerequisite that getting there otherwise would require, and then flies away to let the clarity soak in unhindered by the physical demands of backpacking or the mechanical element of heli-skiing and ski touring – the other options for experiencing these mountains.

Imagine the experience is akin to going on a scenic flight over the Himalaya before taking a scenic walk through the most elaborate arboreal display in the Americas outside of the Amazon. This is where a wheelchair user was lifted out of the helicopter to spend the day on a scenic perch while her family went hiking. She soaked in the experience, tears pouring from her eyes at the opportunity to experience raw wilderness for what was likely the last time in her life. This is where a grandfather taught his grandson to skip rocks across ponds surrounded by sheets of shale broken into a million perfect skipping stones. This is where white-haired couples in their eighties and nineties walk together along high ridges above a sea of clouds hiding the deep valleys below.

Fit hikers cruising in the Adamants. TOPHER DONAHUE.

This is also where a group of backpackers once stomped the words “We Hate You, Hans Gmoser” into the snow after being buzzed several days in a row by a helicopter full of heli-hikers. In the summer, logging roads give non-motorized hikers, at least once they leave their cars, access to some of the heli-hiking terrain, so the heli-hiking guides are tuned in to other backcountry users in the area. Popular backpacking routes are avoided entirely, but the mere concept of helicopter-driven mountain sport is enough to raise some people’s hackles.

After my first experience with CMH, a heli-climbing trip in the Adamants, I wrote an article for Climbing magazine describing the novelty of bagging first ascents during daily excursions from the comforts of the lodge. In the next month’s issue, a letter to the editor described the whole idea as “execrable” and a new low standard of wilderness use. It’s a delicate balance between showing people the wilderness and taking care of it. It’s for this reason that CMH hired Dave Butler, a biologist and forestry expert, to monitor the programs and stay in tune with government changes and public perception.

An article in SKI magazine describes the diversity of heli-hikers:

Taking quick stock of this mismatched crowd standing awestruck on a grassy mountain ledge at 7500 feet, I wonder, “How did we get here?’ There’s a 70-something grandfather, a fit heli-skier, a famous chef, an overweight businessman, an elderly lady and a family of five. You’d never guess that in just a couple of hours this wildly diverse group will scramble to the summit and stand together on a lofty peak in the remote Cariboo Mountains of British Columbia.

With the helicopter access, people who never imagined themselves as alpine fanatics can be enthusiasts, devoting as little or as much of their lives as they want to the natural world of the high tundra, the dark blue skies, the tenacious little flowers, the crisp air that somehow flows easier in and out of the lungs, and the forays into the wilderness where it feels like you and your fellow hikers are the only people on Planet Earth. Alpinists discovered this a long time ago and used planes and helicopters to access the most remote peaks, but before Arthur Tauck convinced Hans to take people into the mountains with a helicopter, only the young, the bold, the fit and people with a lot of free time could go out there and live it.

Reflections in the Unicorn Meadows of the Adamants. TOPHER DONAHUE.

While the spectacular arena is why most people sign up in the first place, as with heli-skiing, it’s only part of the magic. Emmy Blechmann, a hiker from Idaho, said, “You know what is the most exciting part of this whole thing? The helicopter. It is so thrilling to get off the bus after a long trip and suddenly be flying over the treetops and into these amazing mountains you’ve been looking at from the bus windows all day!”

She continues, in response to the mountain hospitality, “I’ve been all over the world, to the fanciest retreats and resorts that cost way more than this, and this is the best I’ve ever been treated – better than anywhere else.”

Indeed, there is no environment on earth where you can make friends faster than in the mountains. This is true regardless of the season. Something about the isolation, the way the old hills make a person feel young, mortal and lucky to have a chance to explore.

The guide’s job is to give people with vastly different abilities, ages and strengths an ideal experience. During the ski season, gravity helps to help keep people together, but in the summer there are marathon runners, overweight executives and patient seniors visiting at the same time. The solution is to have more guides with smaller groups so people can do their own thing at their own pace.

One of the lodge staff observed, “On the first night the (dining) room is pretty quiet. On the second night there’s a lot of conversation. And on the third night it is downright noisy in here. People show up as strangers and leave as friends. It’s really inspiring.”

The summer program today is about where heli-skiing was in 1969. The guides and staff are inventing it as they go, accommodating the changing desires of the kinds of people who want helicopter access. Younger guests are inspiring more adventurous and demanding routes, while family groups often want less mileage and more opportunity to relax together.

Some hikers have become as enthralled with the experience as heli-skiers. To honour their devotion to the game, the lodge staff gives an award, called the Alpinist Award, to anyone who has spent 15 days heli-hiking. When Barb Ostberg received her award – a hiking kit including a jacket, pack and water bottle – she blushed and said humbly, “The last person in the world who should be called an alpinist is me.”

For people like Ostberg, the helicopter is the only way she’ll ever find herself, many kilometres from the nearest road, walking along an alpine ridge towards a remote summit in anticipation of the view from the top – a vista rivalling the infamous perspective from the summit of Mt. Everest, with peaks and glaciers stretching to the horizon in every direction. For her, it is Everest, a place where she can strive for a lofty perch and feel the pulse of this rugged planet, a place where she can focus on taking the next step in tune with the rocks, ice and life around her, a place where she can forget about the rest of the world for a moment.

Some of the most sublime acreages on the planet are frequented by heli-hikers. These places have never been on Outside magazine’s hot 100 lists, photos of these places have never been in National Geographic, and Outdoor Life Network has never made a show about them. Yet, they rival all of the places featured in these famous publications and productions. With a road nearby, there would be walkways built with signs marking the best views, overlooks built on rock outcrops with pay-per-view telescopes, and a Relais-et-Chateaux-worthy hotel and restaurant would be built on the tundra nearby. Instead, they remain unnamed, except unofficially by a few guides who needed some nomenclature to communicate with each other, and unknown except for the memory and photo albums of a handful of lucky people who fly there each summer while heli-hiking.

One of the areas is a natural golf course, aptly called the Ninth Hole, perched at the edge of a precipice overlooking the terminus of the North Canoe Glacier in the Cariboos. The glacier ends where the ice reaches the edge of a skyscraper-sized cliff, and while part of the ice has tenaciously clung to one side of the rock, creating a cascade of frozen chaos with ice pillars and blocks the size of houses defying gravity, the other half has fallen away, leaving bare rock below the ice. Waterfalls burst from the ice, pumping the very lifeblood of the glacier over the stone at a phenomenal rate. The waterfalls have no name but would be world famous if anyone knew about them. Walking up to an unnamed, unknown waterfall in a setting that could be the eighth wonder of the world is an experience typically reserved for only the most audacious explorers.

Unicorn Basin in the Adamants is an otherworldly meadow with lush flower gardens and speckles of tiny ponds reflecting black spires and white glaciers hanging over the ridges above. It is the sort of drainage that inspires fantasy writers to describe the birthplace of rainbows or unicorns. Underfoot the foliage is so lush that the sturdy growth prevents a hikers foot from reaching the ground. The basin is named after Unicorn Mountain, an 800-metre-tall, horn-shaped black spire perched atop the cirque. Unicorn Basin is located on the rugged side of one of the most glaciated and precipitous areas in the Columbias, the headwaters of Austerity Creek. No logging roads penetrate the valley, and the massive black bulk of Mt. Remillard and the great granite cathedrals of the Gothics hide the area, enhancing its isolation.

One of the most unique spots frequented by heli-hikers is a rocky and often windy place named Anthea’s Anatomy by typically irreverent heli-skiers. Had this spot been found by explorers, it would likely have been called something more like Eagle’s View. It is a high moraine left by the bulldozer of the Conrad Icefield, the biggest icefield in the Columbias, when it receded. A series of tundra-covered ledges at the edge of a cliff make for idyllic viewing platforms to gaze across the ice from a perspective most often reserved for birds. Looking down onto the old ice, criss-crossed with crevasses, you can see each winter’s snowfall preserved in the ice, telling its story like the rings in a tree. Dark layers mark each summer, where dust from winds and ash from forest fires were blown onto the ice, and lighter layers mark each winter’s snow accumulation. Recently, hot summers have melted the previous winter’s snow entirely, leaving no story in the ice at all except for the tale of what’s not there: the snow that has disappeared down the rivers draining into the mighty Columbia and on to the Pacific. It is one of those rare places where you need no understanding of science or precision instruments to see climate change even relative to a human lifetime.

In the Bugaboos, an area of uncountable beauties, there is a place of almost unnatural artistic balance between a meadow cut by sparkling streams accented by brightly coloured flowers, a ridge bristling with the symmetrical forms of pine trees, and the castle-like bulk of the Howser Towers standing against the ever-changing mountain sky. The small but vibrant flowers, some no bigger than a grain of wheat, can be seen in the same view with the lifeless granite wall of the Howsers rising a vertical kilometre high and two kilometres wide just beyond the pine trees. It is a scene where our sense of scale is titillated with the visual anomaly of something very small standing proud against something very big. The area is unassumingly called Kick Off, and it is a ski run in the winter that overlooks the unsurpassed grandeur of the East Creek drainage, an area seen only by heli-hikers, heli-skiers and a handful of adventurous climbers who enjoy the remote challenge of exploring the famous west face of the Howser Towers.

A team of heli-mountaineers in the Adamants ascend the easy yet thrilling glacier en route to the summit of Mt. Remillard. TOPHER DONAHUE.

As unique as it is to have an area the size of a national park all to yourself, the helicopter does a disservice to the reputation of the experience. Who needs a helicopter to go hiking? Almost anyone can drive their car to a trailhead and go for a perfectly lovely hike. We don’t call it auto-hiking just because we use a car to get to the hiking areas. The helicopter is such an unusual, exciting and expensive means of transportation that it overshadows the experience of spending time in these places. While heli-hiking has been happening since 1978, its potential was largely ignored by traditional backcountry users until recently.

My first experience with heli-hiking was as a photographer. Instantly I recognized the value of the helicopter as a tool for finding a perfect location without having to carry a backbreaking load of glass for hours. It gave me time to shoot, free from the worry of making it back to the trailhead by dark. I could spend hours in the alien world of macro lenses: chasing the sun as it caught the delicate golden petals of a glacier lily, trying not to dislodge drops of dew while manoeuvring a tripod to shoot them clinging to the hairs on the delicate purple petals of an anemone, shooting air bubbles just beneath the ice at the toe of a glacier, and trying in vain to catch a bee as it feeds on the vibrant red heart of an Indian paintbrush.

With a camera kit I would never carry into such a location, the compositions are infinite. With a big telephoto lens I could juxtapose a lush field of wildflowers against the blue-grey of a glacier’s snout, slow the shutter to let a river blur into silky patterns below a craggy peak, pose hikers next to an ancient glacier in front of a gaping crevasse, frame lofty spires against a billowing thunderhead – all the while knowing there’s a helicopter waiting to lift us to safety before the storm hits.

Even with a simple point and shoot camera, the opportunity for phenomenal photos is everywhere. More than one person arrived on a heli-hiking trip as a casual amateur photographer and left as a committed shutterbug. Everywhere you look, a postcard or cover photo meets the eye. The hard part is making it look as good in the photo as it appears while standing there immersed in beauty.

Crossing the suspension bridge of the Mt. Nimbus via ferrata in the Bobbie Burns. TOPHER DONAHUE.

For hard-core hikers, the potential is just beginning to be realized. The 20 kilometres of the gently rolling Grizzly Ridge between the Bugaboos and Bobbie Burns would be a world-class trail run or a long day hike past the jagged teeth of the entire Bugaboo and Vowell ranges. The 15-kilometre-long rim of Alpina Basin in the Adamants is like a huge margarita glass, with ice rather than salt lining the rim, and tundra, lakes and gurgling streams where the tequila and lime would be. The Adamants’ manager, Erich Unterberger, and a particularly motivated hiker from Boulder, Colorado, traversed the entire rim in a single day. It entails easy snow walking and a view of Sir Sanford’s grey and icy hulk on one side and the sea of glacier on the other. This kind of heli-sport could be a wave of the future, but for now the majority of hikers are still more interested in relaxing hikes through jungles of wildflowers to reach a lunch spot above a tarn rippling with the reflection of lofty peaks and crumbling glaciers.

Climbers are also experimenting with the helicopter access from the lodges built for heli-skiing. A heli-mountaineering program has been growing slowly, but few mountaineers have realized the true potential. Most climbing areas today are recorded in guidebooks with such detail that it removes much of the adventure from the experience. Maps of each climb are drawn in detail, giving away many of the secrets of the rock, to the point where climbers know exactly what equipment to pack, how long the climb will take, even what size cracks to expect and how difficult each passage will be.

Because of the pure adventure involved and the chance to go where no human has ever been, first ascents are the proverbial feather in the cap for climbers. In places where most climbers live, every summit has been climbed, and first ascents can only be found, if at all, in between cracks and faces that have already been climbed. To do a first ascent is the ultimate climbing experience and is one of the rare times in this modern world where we can be true explorers of geography, touching a piece of our planet that has never been touched, seeing a view that has never been seen, spending a day as no human ever has. It is a chance to play Ernest Shackleton in a microcosm where success is not certain, difficulty is unpredictable and finishing is a chance to make history.

After a first ascent, the climbs are recorded in guidebooks and by alpine clubs. The Bugaboos and the Bobbie Burns lodges both have world-class mountaineering programs, but the Adamants is the climber’s bonanza and the potential is just beginning to be explored. The Adamants are particularly well endowed with steep rock faces. Many are named, some have been climbed and a number have yet to be explored. Many faces have never felt the touch of a human hand, and it is every climber’s dream to walk up to such a piece of rock and be the first person to ascend the wall. The golden age of heli-climbing has yet to happen. The climbers who can afford the access don’t yet realize that a week in the Adamants can give them more first ascents than most climbers will do in a lifetime. For mountaineering, the Monashees is the least developed of areas, and future adventurers will find lifetimes of classic mountaineering routes on the range’s spectacular peaks.

Monashees powder and terrain changed tree skiing. TOPHER DONAHUE.

While the guides call the technical ascents heli-mountaineering, and typically focus on spectacular routes of relatively moderate difficulty, a group of rock climbers from Boulder, Colorado, wanted something more: heli-climbing. They wanted the helicopter to drop them at the base of the most remote rock faces in the Columbias for a day of climbing and a return flight to the lodge in the evening.

Heli-climbing in the Adamants began when a heli-skier from Boulder named Kyle Lefkoff saw the opportunity to do numerous first ascents while based out of the Adamants lodge, with gourmet meals on a table rather than ramen in an oatmeal-stained pot, fine wine from a glass instead of Gatorade mix from a Nalgene bottle, a hot shower in place of a cold stream, a massage replacing a long walk back to camp, and a private bedroom instead of a cramped and fetid tent. Boulder, being statistically the fittest city in the United States, was an ideal place to recruit someone for the most comfortable first-ascent blitz in the history of mountaineering. He found a willing partner in a climber named Wayne Goss. In an essay titled “A Brief History of Heli-climbing,” Lefkoff wrote:

We finally got serious in the winter of 1994, after back-to-back ten-day trips over Christmas and New Year’s in the Adamants convinced me of the correct venue, and of the right guide for the job: Erich Unterberger. Erich was the assistant manager to Franz Fux in those days, and Fux ran a tight ship. But I’d never met a guide as motivated and committed to climbing his range as Erich.

The next season, Wayne and I were invited to join Brooks and Ann Dodge and Art Dion on an Adamants tour. We thought this would be our perfect entrée to heli-climbing, but Ann sent us all a flower book for the trip, and a half hour call with Fux and Mark Kingsbury (“you want to climb what!?”) convinced us we were barking up the wrong tree.

Three years of advanced training for heli-climbing ensued (“climb, spa, drink, repeat as necessary”) until Goss and I got our big break: Fux left CMH and Erich was in charge of the Adamants. We made a solemn vow: if Erich would let us climb what we all wanted, Goss and I would bring the A team to the Adamants. All the promises were kept, and in August 1999 we showed up at the lodge with a crew of legendary Boulder climbers, all with decades of first ascents around the world.

It wasn’t just the miles of untouched alpine granite. It wasn’t just driving a 212 (helicopter) around the ranges like a Chinese rickshaw. It wasn’t just rolling out of bed at 8 a.m. for a big breakfast and then roping up at the base of the wall at 9:10. And it wasn’t just sending the big lines for the first time, ever. No, it was doing all this stuff that all of us lived for, and then making it back for a 4 p.m. massage and hot tub, a decent martini and a fine bottle of claret at dinner.

Lefkoff returned to the Adamants numerous times since then, developing the Silver Shadow cliffs on the sunny side of Alpina Basin into an ideal climbing area for beginners and experts alike, doing first ascents on the bigger peaks with his wife, Cindy, and introducing CMH to the potential of heli-climbing for expert rock climbers.

A glimpse into the future of heli-sport? Remote climbing in the Adamants. TOPHER DONAHUE.

While heli-climbing is still relatively unknown, it has graced the pages of Climbing magazine, and with the number of climbers in the United States growing (from 7.5 million to 9.2 million in a single year, 2004), future generations will be looking for unexplored terrain, and the growth of heli-climbing is likely just around the corner.

The heli-mountaineering program, where small groups climb alpine peaks of more moderate difficulty, is already more popular than even the CMH marketing office knows. Many hikers end up feeling the adventurous spirit once they arrive at the lodges, and guides’ enthusiasm for mountaineering inspires them to give it a try. Almost without exception, people return from a day of mountaineering and say, “I just had the best day of my life!”

An expert climber feeling the exposure on the aptly named Ironman in the Adamants. TOPHER DONAHUE.

The Columbia Range contains a fantastic variety of climbing and mountaineering objectives. Some peaks are cut into monolithic spires like arrowheads shaped by a meticulous warrior; others are piles of boulders chaotically thrown together like pyramids built by a lazy god trying to tempt gravity and entropy. The spires and solid walls are better for climbing, but mountains of all types are intriguing to mountaineers. Some, like Downie, the pyramid located prominently down valley from the Adamants lodge, have summits that beg to be climbed but are made of such rubble and broken rock that only a few climbers have ever stood atop them.

While hanging from a few millimetres of rock protruding from the edge of a black wall hundreds of metres above the ground, walking along a ridge with the profile of a kitchen knife, or climbing a steep glacier by swinging medieval-looking axes into the ice may not appeal to everyone, gazing from tiny summits balanced above wild valleys is an experience no one regrets.

A couple of nonagenarians explore the high alpine. TOPHER DONAHUE.

The Adamants and the Bugaboos inarguably have the best climbing of any of the areas, but it is the Bobbie Burns team that is currently carrying Hans Gmoser’s torch of exploration. It began with a dilemma of what to do when the weather shut down the helicopter for an afternoon. The Bobbie Burns guides, mostly restless young climbers – or at least former restless young climbers – felt there was more excitement to be found in the surrounding area during the summer than just heli-hiking.

The Vowell River passes in front of the lodge and enters a narrow gorge complete with powerful waterfalls and frothing whitewater. Thick bush along its shore not only makes walking nearly impossible but also blocks the view of the gorge entirely. Since ropes and harnesses are natural tools for guides, it didn’t take long to decide to build a zipline across the river. Hikers wear climbing harnesses and clip into ropes strung above the rapids, and with a belay to control speed, they zip across the torrent. The roar of the rapids hammers the eardrums, drowning out all other sounds, the exposure of the cliffs dropping into whitewater confuses visual perception, the smell of the lush forest fills the nose, the sensation of speed is enhanced by the cool prickles of airborne water droplets hitting your skin while you fly over the rapids.

The first zipline on the adventure trail in the Bobbie Burns. TOPHER DONAHUE.

The guides called their new outing the Adventure Trail, and it was such a rush among the younger and more audacious hikers that many started asking to do this trail instead of going hiking in the high country. The guides built longer ziplines over the biggest waterfalls in the gorge and assembled an unprecedented zipline that runs 200 metres through one section of the canyon. With guests asking for the Adventure Trail, the guides saw the appeal of combining the stunning alpine locations with adventurous routes using via ferratas.

Between the via ferratas and the Adventure Trail, as well as the traditional hiking and climbing options, the Bobbie Burns summer experience is as unreal, fresh and adventurous as heli-skiing was in 1969. Other lodges are innovating, as well. The Adamants has a long zipline, a ropes course and a few rock-climbing areas that often make a poor weather day into the most memorable and thrilling part of the trip. Fitting to the spirit of Hans Gmoser, the new programs are not the result of marketing decisions but simply evolved from the idea of giving people a mountain experience beyond their wildest dreams.