The 3-dimensional model under glass in the Cariboo Lodge shows why Hans chose the location for his second heli-ski area. TOPHER DONAHUE.

9

It was quite obvious there were other places where one could heli-ski. In fact, virtually all the Columbia Mountains possessed the necessary attributes for good heli-skiing. The question was primarily one of access and accommodation.

— Hans Gmoser

Once the Bugaboos heli-ski model worked, the proliferation of heli-skiing was purely a factor of demand. The other valleys in the Columbia and Cariboo mountains were cloaked with deep snow and sculpted into ski terrain the likes of which people had not yet even dreamed of skiing. During the first forays with Jim Davies’s Cessna onto the Canoe Glacier in the Cariboos, Hans Gmoser and Jim McKonkey were the first skiers to set eyes on much of the terrain. It was stunning. The Bugaboos have their crown-like spires and indisputably world-class skiing, but for pure skiing volume the rest of the Columbia and Cariboo mountains make even the mighty Bugaboos appear insignificant. The sub-ranges of the Monashees, Selkirks and Purcells lean against each other like fish on a string and together contain what is possibly the biggest stash of consistently excellent skiing on the planet. The area contains the only temperate rainforest on earth that receives most of its precipitation as snow, and the terrain is almost all steep enough to ski but not too precipitous to hold snow. One by one, between 1969 and 2003, CMH added 11 more areas to its mountain kingdom for a total tenure of over 15,000 square kilometres of ski terrain – that’s over 200 times more area than Vail and Whistler/Blackcomb combined.

By 1970, the skier’s lust for powder, helicopter capacity that made the business viable and timing with the provincial and cultural climate had combined into a perfect storm of incentive to expand heli-skiing into additional territory. Hans unveiled the potential of the new sport as a recreation industry in a ten-page letter written in 1971 to the BC provincial government. He explained heli-skiing simply as a new concept in ski area development, “To transport skiers by plane or helicopter is not new to this country nor other alpine areas of the world, but it has never been successful to the point where it can be looked upon as an entirely new industry. However, I believe this has been achieved with my approach to the operation in the Bugaboos.”

At the time of the first expansion, into the Cariboos, CMH was anticipating growth of 25 per cent per year, and since the company had already built a full-scale model that was working spectacularly, the province had plenty of incentive to encourage growth in the industry and little reason to restrict it – so the guides essentially went heli-skiing wherever they wanted. While there were unlimited suggestions Hans could have made to the government, he outlined two simple requirements he felt were essential to the successful operation of the “helicopter ski resort”: adequate space and exclusive rights.

The 3-dimensional model under glass in the Cariboo Lodge shows why Hans chose the location for his second heli-ski area. TOPHER DONAHUE.

In his letter, he warned the government of the impending explosion of interest in the sport, based on the CMH business trajectory, and concluded with a plea to establish standards by which CMH and other heli-ski outfits should be expected to operate. By writing the rules of the game in an effort to preserve the resource no matter how popular heli-skiing became, Hans ensured that the heli-ski experience would remain a wilderness one far beyond his lifetime, in more areas than just CMH’s and beyond national boundaries. It took until 1983 – and pressure from CMH, Mike Wiegele and the other heli-ski operators of the seventies – for the government to take action and issue permits for mechanized ski tenures, but it was better late than never.

Hans did the math. More people wanted to go skiing with CMH than the Bugaboo lodge could handle. The year before Hans penned his sagacious letter, Mike Wiegele had begun heli-skiing at Valemount and fanned the fires of Hans’s motivation still higher. Expanding the lodge and the operation in the Bugaboos would have been the most efficient strategy, but Hans, ever the skier at heart, thought about how increased numbers would change the very skiing he and almost everyone who tried it found so beguiling. Hans explained, “After a week without fresh snow in the Bugaboos, we were already finding it challenging and often had to poke around the edges to make fresh tracks and that’s what people come for, the fresh tracks. If we brought more people we would lose the skiing that makes it worth the cost of the helicopter!”

In many ways, these guidelines are Hans’s greatest contribution to the sport. If CMH had stayed in the ski touring business where it began, someone else would have gotten into the game with a helicopter. It doesn’t take a genius to realize that an aircraft is a great way to get to the top of a ski run. If that someone had been equally entrepreneurial but less sensitive to the resource and the experience, the sport of heli-skiing could have ended up merely a very expensive way to go mogul skiing.

A visit to the backcountry lodges like the Bugaboo and Cariboo, or any of the other ten areas under CMH management as of 2008, is now a comfortable, catered experience, but when heli-skiing outgrew the Bugaboos, the business was not ready to pay for the building of another ski lodge. Besides, most skiers chasing Columbia powder at the time didn’t care where they slept. Any building with enough beds to accommodate a group of heli-skiers was fair game, and many areas began with shoddy lodging until the popularity of the area was adequate to pay for a custom ski lodge.

Even before opening shop in the Bugaboos, Hans had been fascinated by the Cariboos’ potential for skiing. Who among those who’ve ever strapped a board or two on their feet could miss it? After carving steep, round-bottomed valleys, the glaciers left the drainages of the Rausch, the Canoe and the North Thompson rivers with architecture that has inspired more than one skier to say, “the Cariboos are proof that God is a skier.”

Jim MCKonkey, decades ahead of his time as a ski stuntman, during an early exploration of the Cariboos. HANS GMOSER.

Avalanches are the original ski run cutters, and when the slope’s angle is consistent, the clearings left by avalanches tend to be parallel sided. When the angle increases, the avalanche paths narrow, and when the angle decreases, the paths tend to widen like water flowing in a river. The angle of the valley walls in the Cariboos is so consistent that mountains are striped with avalanche paths running parallel to each other like the teeth of a giant comb for as far as the eye can see – even from a helicopter. Each of the paths can be skied, and on many of them a runaway ski following the fall line unchecked will end up right at the pickup.

The terrain of the Cariboos is an amalgamation of all the different kinds of features that make up great skiing: the long, powder-cloaked old-growth forests, steep serpentine ridgelines, friendly glades, rock-edged couloirs, undulating glaciers, planar mountain faces and chaotic combinations of all of the above.

Without the advent of heli-skiing, the Cariboos would be unknown to this day. Even with 37 years worth of heli-skiers telling tales of Cariboos powder, and 28 years worth of heli-hikers returning home with photos of impossible fields of wildflowers below teetering glacial ice, the area is still described on the current website of nearby Wells Gray Provincial Park as “the wild untravelled country of the Cariboo mountains, with craggy peaks, icefields and hidden valleys.”

Two years before the first skiers rode a helicopter in the Bugaboos, Hans flew with powder pioneer Jim McKonkey and pilot Jim Davies to the upper Canoe Glacier and began an exploration into aircraft-accessed skiing. During the trip, McKonkey built a kicker, or steep ski ramp, out of snow to jump over the plane as it sat on the glacier. Davies recalls turning the prop sideways to give McKonkey one less thing to hit if he cut it too close. After a few false starts, and one near miss where he slapped the wing with his skis, he stuck it. In a testament to genetics, Jim McKonkey’s grandson is modern big-mountain ski visionary Shane McKonkey, the man called “the craziest man in skiing” by the film company Matchstick Productions for his invention of ski-basing, a gut-wrenching sequence that involves ripping a big-mountain line on skis and hucking off a huge cliff and a spectacular parachute-assisted descent.

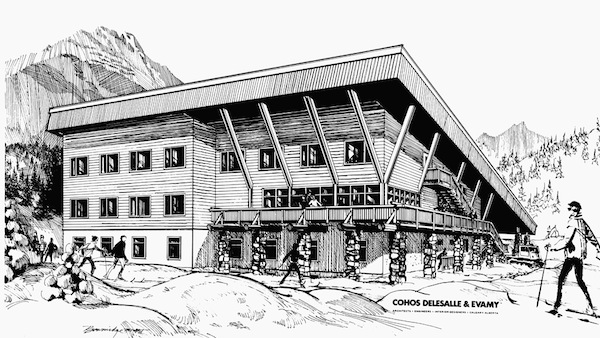

Philippe Delesalle’s original vision of the Cariboo Lodge. Little has changed. PHILIPPE DELESALLE – CMH ARCHIVES.

So massive and obvious is the ski potential in the Cariboos that if there had been no sawmill camp in the Bugaboos to serve as an ideal base for launching the operation, heli-skiing in Canada would likely have started in the Cariboos. The mountainsides just beg to be skied. There are numerous safe and obvious drop-offs and pickups for the helicopter, and with the smaller craft of the day, the location of the present Cariboo lodge would have allowed more efficient access to varied ski terrain than the precipitous, albeit incomparably spectacular, Bugaboos. Thus, when the demand for heli-skiing exceeded the capacity of the Bugaboos, it was an easy decision where to ski next.

Hans was a leader in the mould of Ernest Shackleton and Meriwether Lewis: he led by putting absolute trust in his team. He was utterly confident in his ability to make the right decision, but to make the project move forward he surrounded himself with those he trusted most in the matter at hand and put enormous faith in their abilities and judgment. This rare quality of being a leader who built his decisions out of the input of his confidants created a team of unusual devotion. To make remote heli-ski bases work smoothly, Hans gave each team almost complete autonomy.

A German guide named Hermann Frank was put in charge of the Cariboos skiing, based out of the town of Valemount. For the winter of 1969 CMH still had the monopoly on heli-skiing, but in 1970 Mike Wiegele began offering heli-skiing out of Valemount as well. Hans planned to build a lodge in the Cariboos, but it took four years of bumping skis with his competition before the lodge was completed.

Coming home to the Cariboo Lodge. TOPHER DONAHUE.

Skiing out of Valemount gave the team ample time to study the valleys of the Cariboos for the most suitable location to build a lodge. The Canoe River drainage was too swampy for logging trucks to navigate without significant road-building expense, and the timber within the valley was hardly worth the expense for logging companies to bother with. This gave the area obvious appeal for a lodge location. Even today, there are no logging scars visible from the Cariboo lodge.

However, the very same swamps and scruffy timber were also a hindrance to building a lodge. To accomplish the daunting task, Hans chose another close friend rather than an unknown builder. Lloyd “Kiwi” Gallagher had proved himself to be an unshakable spirit while handling the least desirable jobs and had invested his life savings in the project. He was the perfect choice. Just deciding where to place the lodge was a formidable decision. The ground cover was so thick that planning views, or even seeing more than a few feet into the dense bush, was impossible. Even after choosing the eventual lodge site, Hans, Kiwi and Philippe were unsure how it would turn out. “I clearly remember an epic day!” remembers Philippe. “Hans, Kiwi and I went thrashing through the bush in an attempt to find a better site – without results.”

At this point, Kiwi dove into the Canoe Valley with his family and scarcely emerged until the lodge was finished. The building site became his home and obsession for two years as he managed the construction with the dream of making not only a beautiful heli-ski lodge, but also a place where he would feel at home. “Even today when I get a chance to go into the lodge,” says Kiwi warmly, “I feel like I am going home.”

The early guides were also skilled tradesmen and, with Kiwi at the helm, they poured heart and soul into the job of building the Cariboo lodge. For much of the timber used in the construction, they took trees from the building site and hauled them to a sawmill, where the logs were hewn into boards and beams. Then the wood was hauled back to the site and used in the construction. The beautiful woodwork in the lodge is made of trees harvested from the very land where the lodge now stands. The roads and building site were mud pits, the mosquitoes were thick and Kiwi remembers spending as much time pulling stuck trucks out of the mud as building. It was finished just before Christmas of 1974, complete with finishing touches like guide Franz Frank’s wooden statue of his likeness with a rope over his shoulder and an ice axe in his hand carved into the spiral stairway of the dining room.

Franz Frank’s statue overlooks the dining room in the Cariboo Lodge. TOPHER DONAHUE.

Ernst Buehler, the manager of CMH Cariboos for almost 30 years, is a product of Hans’s leadership style. A mosquito-infested swamp next to the lodge was a huge problem for the summer season, so Ernst took it upon himself to turn it into a lake. After two years of wallowing in the mud, Ernst transformed the swamp into the clear, inviting pond it is today. Later, as corporate oversight crept into the daily operation of the various CMH areas, Ernst was turned down on a request for money to turn the old spa building into a staff house. Staying true to the needs of the lodge rather than the limitations of corporate decision-making, Ernst requested financing to buy a new truck for the lodge. The truck purchase was quickly approved – somehow an expensive truck seemed more important to the budget managers than staff lodging – and Ernst promptly took the money and built the staff house now known as the Chalet. “They weren’t too happy about that,” remembers Ernst, then added, “but Hans made us like owners and because of that we treated these places like our own.” The Chalet still stands, a valuable resource for staff to have a place that feels like home, while the truck would have been scrapped long ago.

For skiing in the Columbias, location was to a large degree irrelevant in Hans’s mind. He could run a heli-ski operation out of almost any valley and produce the requisite skier grins to fill a lodge and pay for a helicopter. So rather than look for the best terrain, Hans kept his ear to the ground for opportunities for lodging. Two hours north of Revelstoke, BC Hydro was in the last stages of building the Mica dam, which turned the northernmost point of the Columbia River, where it bends from flowing north to south, into the extensive Kinbasket Lake. The town of Mica Creek was a bustling village of 4,000 people. The gradual reduction of workers needed for the dam project left enough accommodation for skiers and Hans negotiated with BC Hydro to give skiers room and board for the winter of 1971 in the modular buildings used by the workers.

Trying to keep the Mica Creek Hotel above the snow in the Monashees. ROGER LAURILLA

The skiers ate with the workers in the mess hall, where, as Mark Taggart, one of the original Monashees heli-skiers, remembers, “The workers didn’t really relate to the rich people from the USA who hired a helicopter to take them up the hill.” The workers and skiers also shared the bunkhouse, which Taggart was sleeping in during what was almost heli-skiing’s most lethal accident. At 2 a.m. Taggart was jolted awake by what he thought was a massive avalanche slamming into the bunkhouse, but as he came to his senses he realized the impact had been an explosion. The bunkhouse was heated with propane pumped through the space under the floor and a leak had ignited, lifting the entire structure from its foundation. Half dressed and wholly confused, everyone clambered out the windows and gathered in the parking lot. Taggart remembers people standing around, wrapped in blankets and staring in disbelief as the building “caught fire within ten minutes of the explosion and was totally engulfed.”

Two bartenders were killed in the initial blast and one man was thrown from bed with such violence that he broke his nose on the ceiling of his room. CMH took the group to Revelstoke by bus, supplied everyone with clothing and called US immigration to inform them that 44 people would soon be crossing the border without passports.

After the explosion, BC Hydro built a cluster of houses and CMH leased them for the skiers. A number of Monashees skiers still talk fondly about the days of wading through waist-deep snow from their house to the dining room before a day of skiing. The houses served as lodging for CMH Monashees until 2002 when they completed their most upscale lodge, an edifice framed with colossal wooden beams and featuring walls of windows overlooking the northernmost shores of Lake Revelstoke and one of the most famous heli-ski runs in the world: rime-encrusted trees poking through deep snow for 1300 metres of otherworldly skiing ending at the water’s edge and known as Elevator.

Monashees snow ghosts overlook the Purcells. TOPHER DONAHUE.

When Hans started skiing out of Mica Creek, little did he know that the area would become famous, even among the most experienced heli-skiers, for the combination of heavy snowfall and big-vertical, consistent-fall-line skiing in old growth forests.

Part of the reputation is due to the natural geography and climate of the area, but the Monashees got a reputation largely because of the ski vision of two of the area’s first guides, Sepp Renner and Rudi Gertsch. Tree skiing has become the bread and butter of heli-skiing, far from where it began on the high summits and broad glaciers, but this transition was not because of a business decision. Renner and Gertsch started skiing the trees in the Monashees because it was possible in bad weather and accidentally found a whole new world of skiing. Not only was it more frequently stable enough to ski steeper terrain in the trees, but if they kept skiing the same slope during big storms and breaking up the slab development, they could continue skiing the popular slopes in safety even while the rest of the area was avalanching.

The first time Hans skied the trees with Renner in the Monashees, Renner remembers picking a steep line and when Hans arrived at the bottom he looked at Renner and said, “You’re fuckin’ nuts.”

“Seppie was the one who showed us how to ski the trees,” remembers Rudi Krannebitter. “We were all stuck on skiing the wide-open stuff and only skiing the trees to get to a (helicopter) landing. Seppie was a brilliant skier and he started leading groups through the trees from top to bottom in the Monashees. We saw this and it opened our eyes. He forever changed the way we look at ski terrain.”

The drainage of Soards Creek became the tree skiers’ holy land, a serpentine mountain valley studded with steep hillsides and covered with trees so ideally spaced for skiing that Monashees addicts get to the point where Soards is the only place on the planet where they are truly happy skiing. Twenty-year Monashees veteran Cliff Milleman said, “I tried heli-skiing other places, but I just found myself missing Soards.”

Once dubbed the “Manashees,” because of the testosterone-heavy nature of its skiers, many Monashees skiers are so committed to the place that they book the same week together for years. The fraternity of the Monashees is not entirely different from some groups in other heli-ski areas, but it is most prevalent in the Monashees. On the long bus ride, grey-haired men share earpieces from an iPod, one driving the tune selection and another guessing the song, giggling like a couple of high-school chums. The luxurious new lodge does much to dissipate the frat-house vibe, but it is there nevertheless. Hank Brandtjen has heli-skied for nine million vertical feet, all of it in the Monashees, and misses the old lodging where the construction-project atmosphere was better suited for pranks and manliness. Brandtjen once took all the avalanche beacons, turned them to “Search,’ and hid them in everyone’s rooms. It was the generation of beacons before the Barryvox, and they emitted an audible beep as soon as a signal was detected. Late that night, Brandtjen went out in the parking lot and turned his beacon to transmit, filling the lodge with beeping. After the lights in everyone’s rooms came on, but before anyone had time to pinpoint the noise, he turned his beacon off. Then when the lights went off, he turned his beacon back on.

But although the new Monashees lodge has changed the comfort and aesthetic of the accommodation, the unbeatable skiing, the characters who are addicted to it, and the leg burn that comes from skiing your tenth thousand-metre tree run of the day are the same as when Sepp and Rudi first decided to point their skis into the forest.

There are some ski areas, whether heli-skiing or lift service, that are famous for their reputation, some that are famous for the lodging, some that are famous for the scenery, and there are some that are quite simply about the skiing. The Bobbie Burns is one of the latter. The area takes its name from a mining claim in the area named after the famous Scottish poet Robert Burns. Among students of poetry, Bobbie Burns is known for womanizing and writing poems of witchcraft and songs that have become traditional ballads. In skiing, the name is famous for massive daily vertical, non-stop runs, fit guides, a majority of non-English speaking skiers and an atmosphere soaked in hard-core ski elite. To minimize wait times in the big terrain of the Bobbie Burns tenure, the program runs with three groups rather than four and the skiers commonly descend 60,000 metres in a week – nearly double the guarantee of 100,000 feet.

An ocean of powder in the Bobbie Burns. TOPHER DONAHUE.

The Bugaboos and the Adamants have an inseparable atmosphere of mountaineering thanks to the setting and history of those areas, but the Bobbie Burns has the strongest climbing culture of any of the lodges. The guides are often found training on the climbing wall and they are constantly looking for new climbs in the rugged peaks in the vicinity. The mountains are reminiscent of the great destination alpine climbing ranges in the world. Mt. Hatteras is shaped like a smaller Gasherbrum IV and the landmark Mt. Syphax looks like a diminutive K2 from some aspects, while Thumb Spire is reminiscent of the rugged peaks of Pakistan’s famous Karakoram Range. Much of the skiing is in remote valleys with such precipitous drops into the Duncan River that even the logging industry has been unable to reach the timber. Skiing and hiking without views into cut blocks and logging roads enhance the big-mountain feel.

It is fitting, then, that the Bobbie Burns began as a ski experience more like an alpine climb from an exposed base camp than a catered heli-ski vacation. The Ruth Vernon Mine, with accompanying dorm buildings, powerhouse and cookhouse, existed near the head of Vermont Creek, a narrow drainage just downstream and on the same side of the valley as the current Bobbie Burns lodge. It was a natural choice after the success of the Bugaboos logging camp, and in 1977, when it was time to develop a new area to meet the booming demand for heli-skiing, the Ruth Vernon Mine was the easiest place to expand operations. There was one small issue: the camp was positioned beneath several huge avalanche slopes, and the skiing in the valley was exposed to large slides. During times of poor stability and bad weather, the skiing options were extremely dangerous and the threat of avalanches made life in the camp downright nerve-wracking.

Big terrain and steep skiing in the Bobbie Burns. TOPHER DONAHUE.

So severe was the threat of slides in the camp that, according to legend, skiers wore their avalanche transceivers to bed. While one guest said he did sleep with a beacon in the Bobbie Burns camp, guide Colani Bezzola remembers it was never required – the camp was positioned on a small island of safety in the centre of the avalanche-prone valley. However, there were times he remembers firmly telling the skiers not to take one step away from the buildings, due to threat from avalanches, and one winter a huge slide pulverized the powerhouse. Massive avalanches frequently ran to within metres of the camp, and the path to the outhouse on occasion was covered with debris. With limited safe areas, the helicopter parked squarely in the centre of camp.

After big storms, the guides flew bombing runs in the cirque around camp. “I remember Frank Stark lighting the fuses with his cigar,” says Colani.

When the bombs triggered the biggest slides, the ensuing powder clouds would engulf the camp, blocking out the sun and causing total darkness inside the buildings for a short time. Avalanche incidents have forever branded the early days of the Bobbie Burns with a notorious reputation.

Once, Colani was guiding and Conrad and Robson, the Gmoser sons, were along for the day. They were cruising through convoluted terrain when the slope on the opposite side of the valley released and slid far enough to bury Colani up to his knees. The Gmosers arrived in moments, but a few of the guests were nowhere to be seen! For a minute Colani and the Gmosers panicked and started back up the hill to begin a frantic search just as the others skied into view. Luckily, one had fallen and lost a ski before the slide, so they were busy digging for the lost ski in a safe place when the avalanche occurred.

Another time, Hans was skiing above guide Hans Peter “HP” Stettler’s group when the slope fractured, releasing a huge slide. HP was directly downslope, but he had enough time and skill – and the slope was steep enough – to point his skis straight down the hill and tuck into the valley and far enough onto the flats to outrun the slide. The rest of his group was in the middle of the hill when it avalanched, but luckily part of the slab never picked up much speed, so some skiers were left perched on blocks while others fell between them. No one was hurt, but shortly afterwards HP changed careers and never went back to guiding.

The boot dryer – not the best-smelling room in the lodge. TOPHER DONAHUE.

Finally, the guides decided this base camp was a little too close to the action, so in December, before the ski season began, a group of modular trailers was brought in to the main valley to serve as base camp. For one season the trailers were home to the Bobbie Burns skiers, and the next year, 1981, CMH built the current lodge. In the early nineties, another danger threatened the lodge – economic recession. The Bobbie Burns was not selling well, so the manager, Bruce Howatt, encouraged CMH to drop the number of groups to three, and inadvertently created the fastest-paced ski program of any of the non-private CMH areas. Now the lodge is one of the first to fill and is a favourite among aggressive skiers. Marion Kingsbury summarizes the modern Bobbie Burns ski program: “It’s not so much that you have to be good to ski here, but you need to be fit and fast. The Bobbie Burns is for people who want to ski!”

It’s no coincidence that most of the CMH areas are found between the first two lodges, the Bugaboo and the Cariboo. Hans explained, “It was mostly flying between the Bugaboos and the Cariboos. It is a long flight, and most of it is over ski terrain. By the time we were thinking of expanding, we knew what was out there.”

In the early seventies, access and accommodation trumped snowfall and terrain, and a man named Roger Madsen ran a business that took people skiing with a plane out of Radium, a small town just south of the Bugaboos. CMH had more skiers than space, so a brief collaboration ensued between CMH and Madsen, called Bugaboo-Radium Heli-skiing. Madsen was a maverick during the most cowboy days of the profession. Long before heli-hiking, he had invented heli-golf. In the off-season he occasionally threw parties for his friends where the helicopter was the golf cart and patches of tundra scattered throughout the southern Purcells were the course. Madsen’s heli-golf was never a business concept, but rather just a spectacular way to have a raging golf party in the mountains.

A series of plane and helicopter crashes rattled Madsen’s nerves, and he offered to share management of the area with Hans and his established Canadian Mountain Holidays team, so Bob Geber took over management of Bugaboo-Radium Heli-skiing. While the ski terrain of the southern Purcells is huge, remote and varied – nearly ideal for heli-skiing – the area sits in the rain shadow of the Columbias and gets significantly less snow than the mountains just to the north and west. The winter of 1977/78 was especially dry and heli-skiing out of Radium was out of the question. The CMH brochure had advertised the Bugaboo-Radium option, skiers had already booked spaces and the only thing lacking was the one crucial ingredient: snow.

A young guide named Buck Corrigan was nervous about his job with no snow to sustain it, so he and Geber approached Hans for advice on what to do. Corrigan said, “Hans asked us, ‘How long has it been since you’ve seen your parents at Christmas? Just go home and come back afterwards. There is always snow in Revelstoke. We can do something there.’”

Hans had explored the heli-ski potential of the Selkirks and Monashees on either side of town as early as 1970, so when he sent Geber and Corrigan over Rogers Pass to find a place with snow, Hans wasn’t just shooting in the dark. Lodging was the first issue, and just by chance Geber walked into the Regent Inn and struck up conversation with the manager, a skier named Fred Beruschi. “We hit it off right away,” remembers Geber. “Freddy was enthusiastic about the skiing in the area. I went and checked out some other places (hotels), but kept coming back to the Regent to eat.”

When ski season arrived, CMH based out of the Regent Inn, and Geber and Corrigan led the skiers into the unknown nooks and crannies of the Selkirk and Monashee mountains on either side of Revelstoke. Remembers Geber, “It was a bit of a culture shock for Revelstoke to have a heli-ski company in town. On the local radio in the morning they would say, ‘Good morning, heli-skiers!’”

Ski guides enjoying a day at the office. GERY UNTERASINGER.

In 2007 a ski resort opened just outside of town that will boast some of the most sustained fall-lines and the most vertical in North America – 1845 metres, or over 6,000 feet – once all the lifts are in place, and the town is buzzing with an infusion of money and energy. In the seventies, the place was little more than a rough logging and mining village on the Canadian Pacific Railway, so suddenly having the word’s rich and famous walking the streets was earth-shaking. One group to arrive that winter included Princess Birgitta of Sweden with her entourage of personal ski instructors. In preparation for the visit from royalty, Hans told Geber, “If we can show her a good time, maybe the king will come.” The week began with terrible weather, and after the second day of no skiing, the princess asked Geber, “What do you have in store for us tomorrow?”

To this impossible question Geber replied, “I don’t know, but next door they have exotic dancing.”

“I guess the boys would like that,” said the princess.

The Peeler strip club is right next door to the Regent, and even today it is a legendary part of the Revelstoke ski experience. When Beruschi heard of Geber’s plan he said, “You can’t take the princess to a strip show!”

To which Geber said, “Aw, come on, some good Canadian lumberjack culture would be good.”

“What would Hans think?”

“He wouldn’t care, so long as she had a good time.”

Skiers take a moment to enjoy the rugged terrain above Revelstoke. TOPHER DONAHUE.

That night Geber went to the club with the princess, her two personal ski instructors, her brother-in-law and a German baroness. The next day Geber suggested the princess ski first down a run that had never been skied and named the run after her. Later, the King of Sweden did visit, so Geber’s tour of Revelstoke nightlife and skiing must have received rave reviews from the princess. It is not known whether the king checked out The Peeler.

While Geber was the first manager of CMH Revelstoke, it was Corrigan who put it on the map. “Buck was the real pioneer around here,” remembers Beruschi. “There is nobody who knows these mountains better than Buck.”

Corrigan took over management of CMH Revelstoke and never looked back. The skiing is a little farther from town than the remote lodges based in the centre of skiing wonderlands, so it took a long time to explore the entirety of the area. Corrigan remembers, “The first ten years were the most fun. We were always finding new runs. It was a riot.”

Although the world is only just beginning to figure it out, in many ways Revelstoke is the snow-sport epicentre of North America. Nearby Mt. Fidelity is home to the snowiest weather station in Canada: it receives the country’s highest annual average accumulation, 1471 centimetres, and the peak gets 144 days of snowfall per year, more than anywhere else in the country. The coastal areas have more precipitation, but it often falls as rain or heavy snow and doesn’t pile up with the feathery depth of Revelstoke powder.

Historically, every two decades another recreational user group discovers Revelstoke. Rogers Pass, an hour’s drive into the Selkirks to the east, has been a mecca for backcountry skiers since the fifties. Then, in the seventies, heli-skiers discovered Revelstoke’s snowy phenomenon, and snowmobilers, or “sledders” as the modern incarnation call themselves, discovered the area’s vast and deep powder fields in the nineties. As of 2008, the word Revelstoke is circulating through lift lines and ski-area bars around the globe. The next decade will likely see the town become a household name among downhill skiers, and change the place forever.

An economic slump in the early eighties put CMH on the brink of bankruptcy, but by the end of the decade the future of heli-skiing had regained a rosy colour, and Hans’s motivation to expand and accommodate more people continued with conviction. Walter Bruns, the director of operations, Mark Kingsbury and Hans Gmoser moved quickly to open new terrain to meet demand, and in just four years CMH started operations in three new areas. In 1987 available ski tenures were becoming few and far between. To avoid speculation and the possible leak of a new area, Hans secretly studied topo maps of the area between the Revelstoke tenure and the Monashee tenure, then drove around the logging roads to see as much as the view from the valley bottoms could reveal before chartering a plane for a day to see it all from the air. The research convinced him of the skiing potential in the region, and without telling anyone in his office, he applied for the heli-ski tenure to everything between the Revelstoke and Monashee terrains to the north and south, and everything between the great bend of the Columbia River where it turns from north to south. A modern mine near the confluence of the Goldstream River and the Columbia had adequate lodging, so CMH purchased a couple of ramshackle buildings from the mining operation.

The original Gothics lodge was the tackiest heli-ski base in history. Pink metal pillars and modular bedroom wings were connected by a hallway of plywood so long the staff would leave bicycles at either end to more quickly move through the claustrophobic tunnel. Today the pink pillars are long gone and the long plywood tunnel has been replaced with a glass hallway, a spa and an exercise and meeting room.

The Gothics are home to the longest named run in CMH tenure, Endless Journey, a 7,500-vertical-foot odyssey from the top of a peak at the head of Horne Creek. The biggest possible ski run in CMH is lost in history with the recession of glaciers, but according to legend, at one time 8,500-vertical-foot runs were skied in the Cariboos, and equally long runs are still possible. Today however, adventures down long descents are out of fashion, and fall lines are more important than exploration, so these long runs would be more of a ski tour than a fall-line ski run. The Gothics is also home to the most famous run in CMH tenure, Run of the Century. While skiing Century is a feather in the cap of any heli-skier, the guides will tell you there are better runs in the area, like the mind-blowing Downie Left, which has a lesser name but a better fall line for much longer. Indeed, the Gothics are all about skiing on stunning features. Many runs start on the very summit of a peak, and the mountain range itself is a testament to natural symmetry. From high viewpoints, perfect ridgelines recede into the distance, each the same angle and size, each with a perfectly pyramidal peak at the top.

The skiing in the Gothics is as diverse as it gets. Roger Atkins, creator of the Snowbase database used by CMH to track snowpack, animal habitat and other mountain issues, says, “The real judge of a heli-ski area is the skiing that’s available in poor conditions.” In this sense, the Gothics is one of the best. When only one elevation or aspect offers good or safe skiing, the options for high pickups are numerous and it is easy for guides to find fun skiing away from the big features that can send avalanches running up the opposite side of the valleys. And when conditions are stable, the options are limitless. The vast snow ocean of the Ruddock Creek drainage alone could keep an army of heli-skiers busy for days. Undulating alpine terrain drops into friendly glades and ends with the huge tree run of Cougar’s Milk. Even today in guide meetings, discussions of new runs are frequent and nearly every year new runs are added to the run list.

The area not only is versatile for times of poor stability but also is uniquely suited for skiing with groups of mixed abilities. Mellow lines suitable for weaker skiers can be found right alongside steep runs that will steam the goggles of the most skilled. Big glacier runs with views of the impressive Gothics Range are easy enough for neophyte powder skiers, and nearby, the powder pocket of Marshmallow is considered a favourite run among CMH staff, who find the numerous terrain features a playground for snowboard aerials.

With the opening of the Adamants lodge in 1990, the area was split in two, with the Gothics severed by the tenure division from their namesake peaks and glaciers, which are now in the Adamants terrain, but Adamants and Gothics groups are known to poach each other’s runs, since it is all part of CMH terrain.

Partly because of the mountains, and partly because of the energetic leadership of Claude Duchesne, the charismatic French-Canadian area manager, and Ian Campbell before him, the Gothics have developed a loyal following. Duchesne was working in the mine when he learned how much more fun the staff was having at the heli-ski lodge next door. He decided to get his guide’s ticket and, as fate would have it, ended up managing the lodge years later. Guest Christian Gmoser (no relation to Hans) has made the trip from Finland to ski over a million feet in the Gothics. When the lodge was renovated in 2006, Christian travelled from Finland to pitch in with the remodel. By leaving the bar, dining room and kitchen wing separated from the sleeping quarters, skiers who want the après ski to last all night can carry on without disturbing those who want an early, quiet night in the northern Selkirks. “It’s the best party lodge in CMH!” says Duchesne proudly.

Mark Taggart, a skier from Colorado who has sampled most of the Columbias’ runs, remembers the Gothics as a combination of big snows and good parties. “When we arrived we’d reach down out of the window of the room to put our beers in the snow to keep them cool. By the end of the week it snowed so much we were reaching up out of the window to put our beers in the snow!”

The most famous ski run in the Columbias: Run of the Century. BRAD WHITE.

In the morning, with or without hangovers, it is time to go skiing. When conditions are good, the Gothics are still ripe for exploration. The big symmetrical peaks hide untouched valleys, and guides await the right group of strong skiers during a period of good stability with a big snowpack to discover terrain that has never been touched by a skier.

A ski guide sees tracks where no one has been, and even in the late eighties the CMH guides still had a vast horizon studded with unexplored ski terrain to choose from. By this point, the team had developed a deep understanding for what made for a smooth operation. Consistent snowpack, varied options for bad-weather flying and skiing, the thickness of the forest, the shape of the high peaks and the condition of the glaciers all made the difference between down days and powder days.

Skiers were crying for more heli-ski spaces, and there was unclaimed heli-ski terrain in the southern Selkirks, but the mountains there were unlike the other areas. The convoluted peaks that have become known as Galena are generally steep, rockier than the rest of the Columbias, heavily forested below treeline and exposed and steep above treeline. While the guides saw enough potential in the area to pay for the Crown-land tenure and build a lodge, the CMH management decided to build a less expensive lodge in case the area failed to attract skiers in the same numbers as the other areas.

“At the time, we thought we’d come across the perfect template for the future of heli-ski lodges,” remembers the head of CMH marketing, Marty Von Neudegg. “Mark (Kingsbury) and I thought we were so damn brilliant in the simplicity and economics of the design – and now we’d like to replace it.”

Galena was the first remote lodge to be built since the Bobbie Burns, and was a significant departure from the design of the other three CMH lodges. The modular architecture is tastefully trimmed in logs and painted an earth brown, so the lodge avoids the trailer-park look, but the sleeping quarters are a string of ready-made dormitory modules attached to a simple three-storey living area and kitchen. Because the bedrooms were built at ground level, strong slats had to be retrofitted over windows to keep snow avalanches off the roof from smashing through the windows.

The Galena lodge is comfortable but utilitarian, and it feels more like a summer camp than a luxurious ski lodge, but there are no guest complaints and Hans needn’t have doubted its popularity. Once skiers discovered the adventures waiting in Galena, the name became synonymous with technical skiing through old-growth forests in over-the-head powder. Now, a new lodge for Galena is on the drawing board. Some guests, however, have grown quite attached to the original building. A skier named Greenie, henchman of the hard-partying Australian group that invades Galena every year for the early season, has visited the other lodges but prefers Galena in part for the lodge’s atmosphere. “I like this lodge best,” he says with conviction. “I like the other lodges too, but they feel like resorts. This feels like a clubhouse – my ski clubhouse.”

But even if CMH does build a new lodge at Galena, Greenie and his rowdy crew of surfers from Down Under will likely still make it home each December for one reason: they are utterly addicted to the skiing. If the Cariboos is proof that Mother Nature is a skier, Galena is proof that she is a skier with a twisted sense of humour. Most of the runs are Tolkien-meets-Dr.-Seuss epics through convoluted forests over plentiful pillow drops, and down ever-steepening faces. The trees, heavily laden with the tenacious snow of the southern Selkirks, take on personalities of all shapes and sizes.

Geology is at the heart of all ski terrain, but Galena’s namesake and unique skiing is all about rock. Galena is a mineral, a crystal of lead sulfide, and the Galena ski tenure is along a heavily mined fault line between sedimentary and metamorphic zones that is generally younger than the rest of the Columbia Mountains. Geologists describe the area as “highly deformed,” and skiers who’ve been there would agree. Miners took advantage of the exposed folds of stone to access gold and silver veins starting in the 1890s, and today their mineshafts are another hazard for skiers to avoid. The same forces of folding that reveal mineral-rich mines left mountainsides shaggy with millions of small cliffs yet to be smoothed by the powers of erosion. Add an annual snowfall of 18 metres and you get what Derek Marcinyshyn, a four-year Galena guide, calls “the best terrain park on the planet!”

John Byrnes, a die-hard Galena fan, describes a misadventure getting around a cliff on a run near Pair-a-Dice:

But where in the hell am I supposed to go? Murray takes about 13 metres of air and lands it. After a totally immature celebration of the event, Fin manages to duplicate it. Shit. I’m stuck up here. Murray yells to go left. I thrutch for about ten minutes, but the smaller cliff he’s aiming me at is ugly with rocks and trees and stumps sticking out, and is still eight or nine metres high. Finally Murray points out a small chute with trees growing in it. I commit to it, and start sidestepping down. I’m basically down-climbing this thing by lowering myself branch to branch like Tarzan. My skis are 190 cm, and the chute is a bit narrower than that and about 50 degrees. After stepping past a pongee-stump, I can finally jump in the air, pivot my skis downhill and take the final three-metre drop. I rated it 5.4 (a rock-climbing grade).

This is not the place to stand at the bottom of a run and admire your perfect tracks. Most of the time you look back and see three or four turns – or one. It’s not only the trees; the undulating terrain prevents the picturesque but somehow homogeneous “heli-spooning” so common in other areas, where each skier lays their track right next to the track before them. To ski safely in Galena, skiers are expected to take on a bit more responsibility for their skiing than in areas where the guides can more often watch the skiers as they descend. Many runs descend truncated ribs, narrow ridges that split into two or more ridgelines with steep faces in between. Imagine following the edge of a massive pyramid that is cleaved off partway down the edge, leaving two edges. A skier who chooses a trajectory one degree different from the group on top can end up on the wrong edge, leading to an entirely different side of the mountain and ending at the bottom of the valley several kilometres away from the rest of the skiers. In microcosm the same holds true: skiing left of a tree island can be easy, while to the right is a morass of jagged boulders and big drops.

Galena terrain brings the best out of guides and guests. The guides typically explain the run from the top and point out the pickup and specific hazards before disappearing from sight in a ball of swirling snow crystals. It would be easy to mistake their hell-bent blast to the next strategic stopping spot as irresponsible, but in fact their reasoning is just the opposite.

Roger Atkins, a veteran Galena guide and a survivor of nearly every pitfall that can happen to a heli-skier, explained the reason for skiing with minimal delays: “If we stop frequently, people end up blowing past us in the trees, the group gets below me and the fall lines become harder to follow. If something goes wrong there’s not much we can do in this deep snow except get a ride back to the top and descend again. If there is an issue, by waiting around in the trees we’re just wasting time.”

Guides in every area use the same strategy – and skiers encounter truncated ribs and deceptive terrain in heli-ski venues all around the world – but the volume of rugged terrain at Galena is unsurpassed. It is evident in the very bones and muscles of the Galena guides. During CMH guide training, an occupational therapist named Delia Roberts spends each evening giving therapy advice for specific ailments. On the night she announced, “Back issues will be the topic of the evening, so anyone with back issues raise their hands,” all the Galena guides’ hands shot up.

The spine pays the price for the mandatory drops that are the name of the game in Galena skiing. The terrain catches even the most veteran guides by surprise. Rock crevasses lurk in the forests and are traps of a sinister kind once they are buried in midwinter snows. Cliffs that seem benign from above turn out to be huge, and tempting rollovers reveal massive air.

“You ski over four of those things and it’s a fun little rollover,” says Galena guide Bernie Wiatzka with his eyes widening. “Then you ski over the fifth one – and it’s a cliff!”

“It’s the most challenging place to guide of all the CMH areas,” another guide claims. Of course, the most difficult place to guide is the one with the worst conditions on any particular day, but even the easiest day at Galena holds a whole lot of question marks.

Just a year after the Galena opening, CMH divided their huge Gothics tenure roughly in half and built a lodge with a view to rival even the iconic Bugaboo lodge setting: the Adamants lodge, located near the head of the Goldstream River in the heart of some of the most rugged mountains in North America. When it opened in 1990 it was the most luxurious of the CMH lodges and set the standard for future development, but like the other CMH areas, the lodge is dramatically overshadowed by the surrounding mountains.

If a major highway crossed the Adamants, resorts would dot the area’s phenomenal scenery, five-star hotels would be built on the most spectacular viewpoints, YouTube would have thousands of clips of the scenery, and the Adamants would join Yosemite, Chamonix and the Bugaboos as one of the most famous mountain areas in the world. Even when compared to the famous Bugaboos, the Adamants is the most precipitous area in the Columbias, but because the logging roads end shy of reasonable automobile access, much of the area remains exclusively the realm of heli-sport. Thousand-metre rock faces have yet to be climbed, massive cliffs have never been touched and skyscraper-sized spires are not even named.

The skiing and climbing in the area owes much of its exploration to the manager of the Adamants lodge, Erich Unterberger. The Austrian ski racer is famous for his enthusiasm for skiing and climbing and is another of the CMH guides whose athletic prowess is hidden beneath his professional persona. At 18 he became the youngest person at the time to climb the infamous north face of the Eiger in Switzerland. In the spring when the sun bakes the snow into velvety corn, he’s been known to set gates on the glaciers for a few runs of heli-slalom. When the snow melts from the faces, he welcomes any and all climbers to the area and has been part of dozens of first ascents, ranging from easy ridges anyone could climb to the most difficult rock climbs in the area.

In the Adamants, it is the summer, when the snow melts off the vertical walls that form a surreal backdrop to the ski season, that demonstrates perfectly why the helicopter is the ideal tool for modern mountain exploration. The cliffs virtually enclose some valleys like the walls of a castle, and with the helicopter, hikers can explore the impenetrable gorges and climbers can scale the sheer walls and exposed ridges. The area is essentially a private Chamonix, a mountain-sport paradise for CMH guests and guides. On the eastern edge of the Adamants tenure, the Fairy Meadows hut serves as a base for skiers and climbers, but the sheer walls to the west keep even the most adventurous climbers and skiers out of the heart of the CMH Adamants terrain.

There is perhaps no other CMH area that is better suited to the vast potential of future heli-sport. Steep couloirs splitting faces of black stone have yet to be skied, and countless first ascents await adventurous climbers with enough cash to pay for the helicopter access. The Adamants guides are quietly waiting for the right guests to truly explore the area’s climbing and skiing potential. In many ways, the summer is the future of the business. “The biggest potential for growth in our company is the summer season,” explains Unterberger. “There are way more people who can do it.”

While Unterberger loves the skiing and climbing as much as anyone, the motivation that keeps him in the Adamants has little to do with chasing his own adrenaline fix. He explains: “I’m intrigued by Hans’s vision of the mountains and what brings people into the mountains and what the mountains can do for people. I draw inspiration from the how Hans saw the world.”

Today, Unterberger sees the next generation of guides in the Adamants learning from the same things Hans used as teachers – the mountains themselves – and pushing the profession to continue to grow. “Hans had this way of putting you in your place, but not directly from him. He let the mountains show you. He never put himself above you, but he challenged you to do the most you could with what you had. I learned a lot from Hans, but now I have guides here that inspire me just as much. They come in with glowing eyes and see things Hans and I might not have seen.”

In the mid-seventies, without any organized business effort, a group of skiers started leading heli-ski tours based out of the lakeside village of Nakusp, a sleepy town perched on the shore of the Columbia River where it is dammed into the 65-kilometre length of Upper Arrow Lake. For years, Kootenay, as the outfit was called, was arguably the most laid-back heli-ski operation in the country. Ken France, the current area manager, remembers the lawless days of Kootenay heli-skiing: “The guide pack (typically full of rescue gear) meant a six-pack of beer and a carton of smokes,” he says with a smile weathered from thousands of days in the sun and millions of face shots.

The operation was run by a tight group of guides who learned their mountains as well as anyone has ever learned a mountain range. While the other heli-ski operations jockeyed for customers and reputation, Kootenay guides were content to just go skiing and the area maintained a low-key reputation and developed a loyal following of guests who loved the area, the steep Kootenay terrain and the après ski soaks in the area’s famous hot springs.

Part of the guiding program in Nakusp is a close relationship with the nearby backcountry ski huts. One of the touring huts, Sol Mountain, is in the heart of the southern Monashees. Each morning, the Kootenay guides talk to one of the Sol Mountain guides, who is standing in the very snow the heli-skiers hope to ski. This way, the heli-ski guides learn exactly what flying and skiing conditions will be like in the committing Monashee terrain, and the touring guides learn what the heli-ski guides know from the vast network of information exchange and real-time weather information available online.

In the world of heli-sport, 1995 was the end of an era. Hans Gmoser completed a smooth retirement from the business by selling CMH to Alpine Helicopters. The entirety of the Columbia Mountains had become a jigsaw puzzle of heli- and cat-skiing tenures. The days of pulling out a map to circle a vast tract of ski terrain, then building a lodge and asking the government for permission later were long gone.

So a year later, when CMH president Mark Kingsbury had the chance to acquire the established local heli-ski business, Kootenay Heli-skiing, CMH purchased the business, with the Kuskanax Hotel for a base camp, and opened the 11th CMH area. Ken France describes the transition: “It was difficult at first because we were proud of what we had and didn’t want anyone to tell us what to do, but it couldn’t have been bought by better people. It (CMH) was an organization run by skiers.”

With the Galena tenure right next door, Kingsbury knew Kootenay was a motherlode. Not only are there the nearly endless options of the southern Selkirks, but the tenure also includes the southern part of the Monashees on the other side of Upper Arrow Lake for those days when stability and weather are perfect and the big alpine terrain around Monashee Lake Provincial Park can be skied. Located between the Monashees and the Selkirks, Nakusp is a natural heli-ski base.

With ski terrain a commodity in western Canada, one flight over the Kootenay region will reveal why Kingsbury moved quickly to add Kootenay to the CMH web of ski paradise. “The difference between the steep skiing here and the steep skiing in Alaska,” proclaimed one guest from Anchorage, “is that in Alaska you can see the steep runs because there are no trees. In the Kootenay we ski just as steep, but it doesn’t look so steep because it is all in the forest.”

According to Roko Koell, “The most stimulating skiing in CMH tenure is in Galena (just across Trout Lake from Kootenay), but the most bang for the buck, with straight fall lines and fast pickups, is Kootenay.” The nature of Kootenay skiing is exemplified in the guy who had “Big Air” written on his skis instead of his name like everyone else to keep them straight in the transition in and out of the helicopter. After a few days, another skier asked him, “Why do you have ‘Big Air’ written on your skis? Do you like to jump?”

“Last year, I went off a 150-foot cliff,” Big Air replied.

“Yeah, right.”

“I spent days in the hospital and months in rehab.”

“Oh,” responded the skeptic, “and you still do this?”

“I love this shit. It’s what I live for.”

The Kootenay region is a maze of ridges with few taller peaks, reminiscent of Utah’s Wasatch Range on steroids. Hundreds of pointed summits dot the horizon with steep faces on all sides. Daniel Zimmerman, an eight-year Kootenay guide from Switzerland, describes the Selkirks as “the kind of mountains shaped like children would draw.”

The famous ski areas of Snowbird and Alta are almost indistinguishable from the surrounding backcountry, indicating minimal tree cutting was necessary to create a ski resort compared to the famous resorts in Colorado and other areas where many runs are virtually clear-cuts in thick forest. Likewise, the Kootenay region could be home to dozens of massive ski resorts, and not a single tree would have to be cut to make fantastic runs. CMH claims 230 runs, but the number is utterly irrelevant. The names are for reference rather than indicating any sort of boundary between the runs. There are hundreds that have never been skied, and it could just as accurately be said that the Kootenay region is one big ski run.

Zimmerman has observed that when guides from other areas work in the Kootenay, “they are always pointing at things and asking, ‘What’s that?’ and I say, ‘We never ski that.’ And they are blown away that we don’t ski such awesome-looking features. We just don’t need to. There is so much terrain.”

Some areas can become skied out during periods without fresh snow, but in Kootenay “skied out” is an unused phrase. Features like the huge Empress Bowl beg to be skied again and again. A frequent Kootenay guest remembers his group counting a thousand tracks down Empress Bowl by the end of a day. The southern Kootenay ski terrain takes time to learn. There are few big peaks to stand out as landmarks in the middle of the tenure, and every face of every ridge appears to be the best ski run around. A typical day includes so many different valleys that all but the most seasoned Kootenay skiers become lost within the maze of ridges and valleys.

After a dizzying day of skiing in Kootenay, the powderfest ends with a flight down Kuskanax Creek. Gazing out the window of the helicopter on the last flight is always meditative and gives time to reflect on the snow-soaked experience while appreciating the phenomenon of helicopter flight. Looking straight down into the powder-laden forest is an optical treat that verges on the hallucinatory. Trees appear to move from side to side as the machine flies overhead, their apparent motion caused by the subtle speed of the helicopter constantly changing the angle of view. While descending the Kuskanax, gazing into the depths of the forest below, you can see the hypnotic patterns suddenly interrupted by the sight of a large semicircular hot tub and upturned human faces peering out of the steaming water of the Kuskanax Hot Springs amidst the miles of frozen forest, and thus begins the most unique part of the Kootenay heli-ski experience. Before the lactic acid has even had a chance to settle into your thighs, you peel off wet ski gear and step into the therapeutic waters of the naturally heated spring. Because the springs are positioned several kilometres into the forested valley of Kuskanax Creek, it feels like part of the heli-ski day, not something that happens afterwards. For those who like soaking in hot water as part of their ski day, the complete Kootenay ski experience is utterly narcotic.

A short van ride back into town brings the skiers, drunk on deep powder and hot water, back to earth. Some of the Kootenay skiing is close enough to civilization that some of the terrain is visible on the high-resolution sectors of Google Earth maps. Zoom in above the Kuskanax Hot Springs and the undeniable symmetry of ski tracks can be seen slicing through a snow-covered meadow.

In the early eighties, the CMH marketing slogan was “The best, the most difficult, the most expensive skiing in the world.” The campaign likely scared away at least as many skiers as it attracted, but one group, four skiers led by a French ski guide from Val d’Isère named Ary Dedet, came looking for the most difficult skiing in the world and found themselves unsatisfied with the pace of the skiing during their week in the Cariboos. Dedet was a private ski guide who had been leading groups in the Alps, including heli-skiing, until heli-skiing was forbidden by the French government in 1981. In looking for a place with unlimited ski freedom, he found CMH and the Columbias and began organizing ski groups to visit the area.

While the Cariboos was expensive, his group was trained on the steep terrain of the Alps and instead of savouring the expected “most difficult skiing in the world,” they spent a lot of time standing around waiting for the group ahead of them. Dedet explained, “The guide was upset with us because we kept passing him as he slowed down for the next group. We told him we just can’t ski this slow.”

The guide was Reinhardt Frankensteiner, and the conversation about staying within the confines of the skiing program continued all week. Near the end, Dedet told Reinhardt, “My group wants to stay an extra week, but not with a regular group.”

According to Dedet, Reinhardt responded, “CMH doesn’t do private groups.” Dedet kept asking about the possibilities, so Reinhardt suggested Dedet contact CMH’s main competition, Mike Wiegele in Blue River. After a single phone call, Mike was happy to arrange a private tour for the French skiers. Reinhardt called Hans to share the developments, and Hans told him, “CMH doesn’t do private groups.” Then, according to Dedet, Reinhardt said, “Wiegele said he’d do it.”

When Hans heard he was about to lose the group to Wiegele, the issue quickly changed from a hassle to an opportunity lost to his most motivated competitor. Hans quickly called Dedet in the Cariboos. Dedet remembers Hans first asking, “You asked Wiegele?”

Dedet replied, “Yes.”

“He said okay?”

“Yes.”

“What do you want?”

“A private helicopter with Reinhardt guiding all week.”

“What did Wiegele say it would cost?”

“It was something like $20,000,” remembers Dedet, “and Hans said okay.”

The next week Dedet got his wish and Reinhardt got the chance to go back to his roots of mountain guiding with a group of four skiers. With only a single group of skiers to consider, the program became much closer to ski mountaineering guiding judgment than the program Reinhardt was now accustomed to while leading 44 skiers around the Cariboos. Dedet remembers Reinhardt having as much fun as the skiers: “After he got comfortable with the group, we did a run where Reinhardt took out a rope and lowered us over a cornice at the top. He was so excited at one point he forgot his pack on top.”

In classic Gmoser style, Hans passed the torch of leadership of the private programs quickly. To promote the new idea, he turned to Marty Von Neudegg, and as Marty remembers, “I think he already knew what to do, but he asked me what I thought we should do with smaller groups in Valemount.”

Hans also went to the Cariboos with the guide he was grooming to be his successor as leader of CMH, Mark Kingsbury, to recruit a couple of guides as leaders of the private program. Danny Stoffel and Stefan Eder were in the Cariboos when Hans and Mark arrived. Stoffel remembers Hans coming up to the two guides and saying bluntly, “We want to talk to you two after dinner.”

Stoffel and Eder looked at each other and immediately thought they were in trouble. Both had been involved in minor near misses over the previous few weeks, and Stoffel remembers, “It was a painful dinner – we were shitting ourselves.”

After dinner, they met with Hans and Mark and were pleasantly surprised to find that, instead of a lashing, they were asked to lead a new private program based in Valemount. Stoffel remembers Hans concluding the conversation by saying, “It’s up to you guys now. You can make it or break it.”

The winter of 1987 was the maiden voyage for the first official private group, and they based out of the Alpine Inn in Valemount. Since then, the private areas of Valemount, McBride and Silvertip have developed comfortable lodging to go along with the steep price tags of nearly $150,000 for a week of skiing with ten skiers. The Alpine Inn was a far cry from the sort of lodging the wealthy skiers were accustomed to, though. Danny Stoffel laughs heartily in describing the lodging: “Each season we would convert one bedroom into a dining room, one bedroom into a living room, one bedroom into an office and one bedroom into a kitchen. A bathroom was converted into a walk-in cooler. We built a contraption over the toilet so you couldn’t see it. At the end of each season we’d take it all apart and put it back together the next year.”

Dedet found the skiing his clients wanted and started booking weeks right away, regardless of the lodging. The lodging was utterly irrelevant – it was all about the skiing. He remembers, “It was so funny to see these rich people spending so much money to spend their holidays in a third-rate motel. They would have never stayed in such a place except to go skiing!”

And according to Stoffel, the Alpine Inn was not only third rate, but beat up as well: “The deck on the hotel was slanted and after a few drinks it got even worse. There were cracks under the doors so big that after a windy night we’d have huge snowdrifts in our rooms.”

They used a beat-up van to reach the helipad, and one day a wheel fell off, leaving the skiers stranded on the side of the road. Stoffel laughs remembering how the incident ended when “the cops drove us so we could go heli-skiing!”

Since then, the private tours have grown in popularity and are based from comfortable lodges exclusively used by skiers, and Valemount is booked years ahead with a waiting list for every week of the season.

With the freedom that goes with guiding a single group, Eder and Stoffel were able to range far from the base in Valemount. Eder explored the vast alpine peaks and remote valleys to the north and returned with reports of excellent ski terrain – enough to accommodate an entirely new operation. When the demand for the private experience exceeded Valemount’s capacity, CMH president Mark Kingsbury asked guide Dave Cochrane to organize a single-group ski program out of McBride, a town with a population of 700 situated along the banks of the Fraser River near the northern limits of the Cariboo Mountains.

While the skiing is plentiful and the area is one of the biggest of the CMH heli-ski tenures, it took several years to arrange comfortable lodging. In 1992 Cochrane was managing a chaotic mix of sleeping in rooms at a roadside hotel, walking across the highway to eat, and even renting a lodge from a new heli-ski operation named Crescent Spur Heli-Skiing during the spring. Guide Kevin Christakos remembers one group of Austrian skiers that arrived in McBride expecting a remote mountain lodge, only to find the in-town lodging did not suit them at all. Before even tasting the skiing, they left, and Christakos remembers one of the skiers saying haughtily as he left, “We can be skiing the Arlberg by Tuesday.”

With a suddenly vacant week, Christakos and fellow guide Greg Yavorski went out the next day to flag landings and pickups. Christakos recalls the two of them flying into the mountains on “a beautiful, cold, blue-sky morning.” They flew over a shoulder of Roberts Peak where they had never skied before and saw a steep, wooded line where a fire had thinned the forest that promised good skiing. Christakos explains what they found: “It was steep tree skiing and the snow was just cold smoke. When we got to the bottom we figured we better name the run, so we called it Better than the Arlberg.”

While Valemount is booked years ahead with a waiting list in case of cancellations, McBride, less than an hour’s drive to the north, is booked only during the high season of February and March. An Italian skier named Andre, who has skied both areas, explained what he sees as the difference between the two: “The skiing is the same, the guides are great in both areas. The only difference is, there (Valemount) the lodge is in the woods and here (McBride) it is in town.”

Due to the vastness of the area, McBride is suitable only for a single group of skiers. The flying time between the different areas would make it impossible for the larger-lodge, four-group program, as each group would spend more time waiting for the helicopter than skiing. For guiding and skiing, the area offers an experience unlike any of the other CMH areas. Christakos explains, “That’s what makes it fun for guiding – it’s such a huge, expansive area.”

And for skiing, there is still opportunity for exploration. The bread and butter areas of McBride are the thousand-metre tree runs of the remote and pristine Betty Wendle Creek drainage and the alpine descents of Castle Creek that Christakos describes as a “land of rock walls, cornices and big terrain where you feel super small.” But there are new areas to explore in the vast McBride tenure. During February of 2008, Christakos was excited by the already fat snowpack. With a gleam in his eye he said, “I expect to ski lines this year that have never been skied before.”

The last area to be added to the CMH empire is also the most unusual. In the late nineties a private fishing lodge called Silvertip on the eastern edge of 100-kilometre-long Quesnel Lake caught Mark Kingsbury’s eye – for good reason. Quesnel Lake is the deepest fjord lake in the world, and the double A-frame lodge is located at the end of the most remote arm of Quesnel, where it reaches deep into the Cariboo Mountains from the western side of the range. Guide Anjen Truffer describes the area: “For people who are looking for the true Canada – this is it.” Even in the summer, a float plane or boat is necessary to reach the Silvertip lodge, located 72 kilometres along the lakeshore from the nearest road. As a ski destination, Silvertip is unrivalled for remoteness, but it is sandwiched between Wells Gray Provincial Park and Cariboo Mountains Provincial Park, and thus a lot of the most appealing terrain in the area is off limits to heli-skiers. When Kingsbury purchased the lodge to use as a heli-ski base, his hope, according to other guides who followed the acquisition, was that some day the terrain would be opened to heli-skiing. According to Willy Trinker, the manager of CMH Silvertip, Mark’s original idea was to begin offering remote fly-fishing as part of the CMH program. “When Mark died,” explains Trinker, “the whole thing (flyfishing tours) kind of fell in the water.” For now, the area is only practical for a single private group and they often ski in the western edge of the vast CMH McBride terrain.

As an experience, Trinker calls Silvertip, “the hidden little secret of CMH.” It is the least popular of any of the dozen CMH heli-ski areas, but it offers something no other CMH area can. Trinker explains: “It is the most like the original CMH. It is so remote it’s hard to imagine. One group even told me after they left that they had a great time but it was too remote for them.”

Indeed, while all the lodges are in the wilderness, Silvertip has the aura of being entirely off the map. With a single group of skiers at any one time, in an area so remote that the nearest neighbor is the Cariboo lodge on the other side of the Columbias, Silvertip feels the most like the original heli-skiing days in the Bugaboos. “It’s a grizzly-on-the-lawn kind of wilderness,” says Trinker. “Once a lady went for a walk along the lake, and when she came back she told the staff, ‘I didn’t know you had a dog up here. It has the most beautiful yellow eyes.’

“‘That’s no dog,’ someone replied. ‘You saw a timber wolf.’”

Today the private lodges attract groups who want the exclusivity of having a lodge and staff to themselves, but in the beginning, and for many groups today, the sole reason for the private lodge is the most basic of all. As Ary Dedet explained, “It is all about the skiing.”

When Hans, Leo and company built each of the lodges and developed the skiing, they made them parts of a single business, but then they hired committed individuals and gave them the freedom to run each area as their own. Today, each area is run by a radically different team, has a different skiing personality and geography, and an entirely different flavour. Roko Koell, who works in almost every area each winter and moves around weekly, says: “It’s like being in a different country every week.”

The collective entity that is Canadian Mountain Holidays is as multi-faceted as a bad snowpack. Hans’s leadership style, built upon by Mark Kingsbury’s touch while the industry changed, influenced this diversity by giving the area managers and staff both huge responsibility and huge freedom to treat the areas as their own. The managers ran their area with the conviction of an owner, not just an employee, from decorating the lodges to developing a skiing style, from the selections at the bar to the food in the dining room, from the fashion style of the staff to the daily schedule. By doing so, CMH became a business that offered not just one experience, but a dozen experiences to be had in different cultures of leadership and atmosphere as well as different topography.

As real estate, the CMH lodges are relatively worthless compared to their value as jumping-off points for recreation access, and as such, they will most likely remain bastions of hedonism for tight-knit groups of skiers, hikers and climbers who want to spend their careers or holidays in mountain isolation.