Comedy Through the Airwaves

MY FATHER WANTED TO BE AN ACTOR and my mother hated the Texas heat, so in 1950, when I was five years old, our family moved from Waco to Hollywood. To maintain family ties, we motored between Texas and California several times over the next few years. On these road trips, I was introduced to comedy. As evening closed around us, my father would turn on the car radio, and with my sister, Melinda, and me nestled in the backseat, we would listen to Bob Hope, Abbott and Costello, the hilarious but now exiled Amos ’n’ Andy, and the delight that was The Jack Benny Program. These were only voices, heard but unseen, yet they were vivid and vital characters in our imaginations. We laughed out loud as our tubby Nash Airflyte glided down the isolated southwestern highways. Listening to comedy was one of the few things our family did together.

Our family in a Texas diner, ca. 1949. Me, my mother, my father, and Melinda. I don’t know who the woman in the middle is, unless we happened to be having lunch with Virginia Woolf.

My father got a job at the Hollywood Ranch Market on Vine Street, sorting fruit. I was taken to see him act in a play, though I was so young I didn’t quite understand what a play was. The performance was at the Callboard Theater on Melrose Place in Los Angeles, and my mother and I sat until the third act, when my father finally came onstage to deliver a drink on a tray and then exit. My father’s acting career stopped soon after that, and I had no understanding that he had been interested in show business until I was an adult.

A few months later, we moved from Hollywood to Inglewood, California, and lived in a small bungalow on Venice Way, directly across from Highland Elementary School. This was the site of my first stage performance, where, in kindergarten, I appeared as Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer. My matronly teacher, who was probably twenty-two, explained that I would be dressed up like Rudolph and—this was the best part—I would wear a bright red nose made from a Ping-Pong ball. As show time neared, my excitement built. I had the furry suit, the furry feet, and the cardboard antlers. Finally, I asked, “Where’s the Ping-Pong ball?” She told me that the Ping-Pong ball would be replaced with lipstick that would be smeared on my nose. What had been delivered as a casual aside, I had taken as a solemn promise; there had never been, I now realized, a serious intent to get a Ping-Pong ball, even though this was my main reason for taking the gig. I went on, did my best Rudolph, and because lipstick doesn’t wash off that easily, walked back home hiding my still-crimson nose under my mother’s knee-length top-coat. One coat, four legs extending beneath.

I was five years old when television entered the Martin household. A plastic black box wired to a rooftop antenna sat in our living room, and on it appeared what had to be the world’s longest continuous showing of B Westerns. I had never seen anything with a plot, so even the corniest, most predictable stories were new to me, and I rode the Wild West by sitting astride a blanket I had placed on the back of an overstuffed chair and galloped along with the posse. I provided hoof noises by slapping my hands alternately on my thighs and the chair, which made enough variation in the sound effect to give it a bit of authenticity.

TV!

The TV also brought into my life two appealing characters named Laurel and Hardy, whom I found clever and gentle, in contrast to the Three Stooges, who were blatant and violent. Laurel and Hardy’s work, already thirty years old, had survived the decades with no hint of cobwebs. They were also touching and affectionate, and I believe this is where I got the idea that jokes are funniest when played upon oneself. Jack Benny, always his own victim, had a variety show that turned into a brilliant half-hour situation comedy; his likable troupe was now cavorting in my living room, and I was captivated. His slow burn—slower than slow—made me laugh every time. The Red Skelton Show aired on Tuesday evening, and I would memorize Red’s routines about two pooping seagulls, Gertrude and Heath-cliffe, or his bit about how different people walk through a rain puddle, and perform them the next day during Wednesday morning’s “sharing time” at my grade school.

My life on Venice Way was spent in close proximity to my mother—the tininess of our house assured it—and I can remember no strife or unpleasantness about our time there. Unpleasantness began to creep into our lives after we moved a few miles away to 720 South Freeman in Inglewood.

MY FATHER, GLENN VERNON MARTIN, died in 1997 at age eighty-three, and afterward his friends told me how much they had loved him. They told me how enjoyable he was, how outgoing he was, how funny and caring he was. I was surprised by these descriptions, because the number of funny or caring words that had passed between my father and me was few. He had evidently saved his vibrant personality for use outside the family. When I was seven or eight years old, he suggested we play catch in the front yard. This offer to spend time together was so rare that I was confused about what I was supposed to do. We tossed the ball back and forth with cheerless formality.

In the second grade, I was in tumbling class. Modern tumbling has nothing to do with tumbling in 1952. Children today spring midair backflips across Olympic-sized arenas right into the arms of Cirque du Soleil talent scouts. Our repertoire included a somersault, a backward somersault, and our highest achievement, the handspring. Next, we would combine the three basic moves into a handspring that turned into a somersault, then into a backward somersault. This might seem impossible to you, but yes, we did it.

One day it was announced that there would be a tumbling competition for second-graders. My father escorted me to school for what seemed like a late-night event, although I look back and realize it couldn’t have been past four P.M. Because our challenges were so simple, the contest dragged on, but finally, enough competitors had stumbled into oblivion, and it was down to me and one other boy. After what seemed like hours, my opponent lost his balance during a forward roll. A flurry of seven-year-olds rushed in and hoisted me up on their shoulders, and I was given a golden loving cup. My father and I walked home in the darkness, and he suggested hiding the trophy under his coat to fool my mom. The ruse didn’t work, because she saw the glow on my face. This walk home is one of the few times I remember my father and me being close. In our house, my mother was called Mama, but my father was always called Glenn.

As a young woman, my mother, Mary Lee Martin, had a sense of fun that was rarely displayed later in her life. She loved fashion, and in an early snapshot, she is striding the streets of Waco in high style. Melinda and I benefited from her sartorial sense; she was an avid seamstress and made clothes for us that she copied from movie magazines. Starstruck, she proudly saved a newspaper photo of herself in a theater, seated behind the popular actor Van Johnson, and later, at age forty-five, she even managed to get some modeling jobs at local department stores. She impossibly dreamed of a glamorous life. I had always assumed the reason my father ended up selling real estate instead of pursuing acting was that my mother had pressured him to get a real job. But when she was older and I presented this idea to her, she said, “Oh, no, I wanted your father to be a star,” and she went on to say that it was he who hadn’t followed his dream. My mother was the daughter of a strict Baptist matriarch who barred dancing, dating, and cardplaying, and she must have viewed her marriage to my theatrically inclined father as an exciting alternative to small-town life. But my father overpowered her easily intimidated personality, and she only escaped from one repressive situation into another.

My mother in Waco, Texas, ca. 1933.

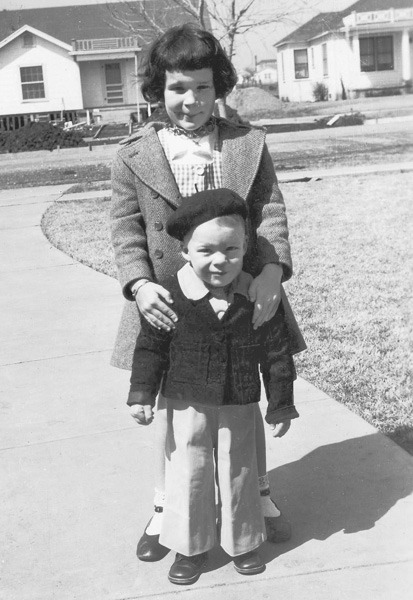

My sister and me in haute couture, hand-sewn by my mother.

Though I was just eight years old, I was, like most children in that benign era, allowed to walk alone the few blocks to my new school, Oak Street Elementary, which opened in the 1920s and is still operating today. It has a wee bit of architecture about it, featuring an inner Spanish courtyard with six shady ficus trees. It is directly under the flight path of LAX, and our routine civil defense drills had us convinced that every commercial jet roaring overhead was really a Russian plane about to discharge A-bombs. One rainy day, fooled by a loud clap of thunder, we dived under our desks and covered our heads, believing we were seconds away from annihilation.

At Oak Street School I gave my second performance onstage, which introduced me to an unexpected phenomenon: knocking knees. I had seen knocking knees in animated cartoons but hadn’t believed they afflicted small boys. As I got onstage for the Christmas pageant—was I Joseph?—my knees vibrated like a tuning fork. I never experienced the sensation again, but I wonder if I would have preferred it to the chilly pre-show anxiety that I sometimes felt later in my performing career. This mild but persistent adrenal rush beginning days before important performances kept the pounds off and, I swear, kept colds away. I would love to see a scientific study of how many performers come down with the flu twenty-four hours after a show is over, once the body’s jazzed-up defenses have collapsed in exhaustion.

MY FATHER HAD A RESONANT VOICE, and he liked to sing around the house. He emulated Bing Crosby and Dean Martin, and my mother loved it when he crooned the popular songs of the day. She was a good piano player and kept encouraging me to sing for her, I suppose to find out if I had inherited my father’s voice. I was shy at home and kept refusing, but one day after her final push, I agreed. I went to the garage, where I could practice “America the Beautiful” in private. A few hours later, I was ready. She got out the sheet music, placed it on the piano, and I stood before her. After the downbeat, what came out of my mouth was an eight-year-old boy’s attempt to imitate his dad’s deep baritone. I plunged my voice down as low as it could go, and began to croon the song like Dean Martin might have done at a baseball game. My mother, as much as she wanted to continue, collapsed in laughter and could not stop. Her eyes reddened with tears of affection, and the control she tried to exert over herself made her laugh even more, with her forearm falling on the piano keys as she tried to hide her face from me, filling our small living room with laughter and dissonance. She explained, as kindly as she could, that I was charming, not ridiculous, but I was forever after reluctant to sing in public.

Having been given a few store-bought magic tricks by an uncle, I developed a boy’s interest in conjuring and felt a glow of specialness as the sole possessor—at least locally—of its secrets. My meager repertoire of tricks quintupled when my parents gave me a Mysto Magic set, a cherished Christmas gift. The apparatus was flimsy, the instructions indecipherable, and a few of the effects were deeply uninteresting. Out of a box of ten tricks, only four were useful. But even four tricks required practice, so I stood in front of a mirror for hours to master the Linking Rings or the Ball and Vase. My first shows were performed in my third-grade class, using an upturned apple crate for my magic table. I can still remember the moment when my wooden “billiard balls,” intended to multiply and vanish right before your eyes, slipped from between my fingers and bounced around the schoolroom with a humiliating clatter as I scrambled to pick them up. The balls were bright red, and so was I.

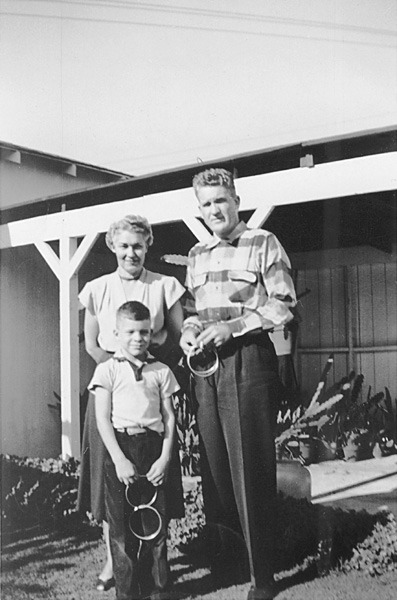

My mother and father, and my Linking Rings, Christmas 1953.

My father was the generous one in the family (my mother promoted penny-pinching habits lingering from her Great Depression childhood; her practice of scrimping on household heat nearly froze us into statues on frosty winter mornings). He annoyed my mother by occasionally lending what little leftover money we had to pals in need, but when my mother objected, my father would sternly remind her that they had been able to buy their first house because of the generosity of a family friend. I loved comic books, especially the funny ones, like Little Lulu, and man oh man, if Uncle Scrooge was in the latest episode of Donald Duck, I was in heaven. My father financed my subscriptions, and I ended up, after one year, owing him five dollars. Though he never dogged me for it, I’m sure he kept this debt on the books to teach me the value of money. As the balance grew, I was nauseated whenever I thought of it. One birthday, he forgave my debt, and I soared with relief. In my adult life, I have never bought anything on credit.

In spite of these sincere efforts at parenting, my father seemed to have a mysterious and growing anger toward me. He was increasingly volatile, and eventually, in my teen years, he fell into enraged silences. I knew that money issues plagued him and that we were always dependent on the next hypothetical real estate sale, and perhaps this was the source of his anger. But I suspect that as his show business dream slipped further into the sunset, he chose to blame his family who needed food, shelter, and attention. Though my sister seemed to escape his wrath, my mother grew more and more submissive to my father in order to avoid his temper. Timid and secretive, she whispered her thoughts to me with the caveat “Now, don’t tell anyone I said that,” filling me with a belief, which took years to correct, that it was dangerous to express one’s true opinion. Melinda, four years older than I, always went to a different school, and a sibling bond never coalesced until decades later, when she phoned me and said, “I want to know my brother,” initiating a lasting communication between us.

I was punished for my worst transgressions by spankings with switches or a paddle, a holdover from any Texas childhood of that time, and when my mother warned, “Just wait till Glenn gets home,” I would be sick with fear, dreading nightfall, dreading the moment when he would walk through the door. His growing moodiness made each episode of punishment more unpredictable—and hence, more frightening—and once, when I was about nine years old, he went too far. That evening, his mood was ominous as we indulged in a rare family treat, eating our Birds Eye frozen TV dinners in front of the television. My father muttered something to me, and I responded with a mumbled “What.” He shouted, “You heard me,” thundered up from his chair, pulled his belt out of its loops, and inflicted a beating that seemed never to end. I curled my arms around my body as he stood over me like a titan and delivered the blows. The next day I was covered in welts and wore long pants and sleeves to hide them at school. This was the only incident of its kind in our family. My father was never physically abusive toward my mother or sister and he was never again physically extreme with me. However, this beating and his worsening tendency to rages directed at my mother—which I heard in fright through the thin walls of our home—made me resolve, with icy determination, that only the most formal relationship would exist between my father and me, and for perhaps thirty years, neither he nor I did anything to repair the rift.

The rest of my childhood, we hardly spoke; there was little he said to me that was not critical, and there was little I said back that was not terse or mumbled. When I graduated from high school, he offered to buy me a tuxedo. I refused because I had learned from him to reject all aid and assistance; he detested extravagance and pleaded with us not to give him gifts. I felt, through a convoluted logic, that in my refusal, I was being a good son. I wish now that I had let him buy me a tuxedo, that I had let him be a dad. Having cut myself off from him, and by association the rest of the family, I was incurring psychological debts that would come due years later in the guise of romantic misconnections and a wrong-headed quest for solitude.

I have heard it said that a complicated childhood can lead to a life in the arts. I tell you this story of my father and me to let you know I am qualified to be a comedian.