Disneyland

A WIDE SWATH OF our Inglewood neighborhood was scheduled to be flattened by the impending construction of the San Diego freeway. The steamrollers were soon to be barreling down on our little house, so the search was on for a new place to live. My father’s decision profoundly affected my life. Orange County, California, forty-five minutes south of Inglewood, was a real estate boomtown created from the sprawl of Los Angeles. It consisted of interlocking rectangles of orange groves and tract homes and was perfectly suited to my father’s profession. Housing developments rose out of the ground like spring wells, changing the color of the landscape from desert brown to lawn green, and my parents purchased a brand-new tract home for sixteen thousand dollars. I was ten years old when my family moved from complicated and historic Los Angeles to uncomplicated and nonhistoric Garden Grove, where the sky was blue and vast but without the drama of Wyoming, just a flat dead sky of ease. Everything from our toes to the horizon was the same, except for the occasional massive and regal oak tree that had defied the developer’s scythe. This area of Orange County gleamed with newness, and the move enabled me to place my small hand on Opportunity’s doorknob.

In the summer of 1955, Disneyland opened in Anaheim, California, on a day so sweltering the asphalt on Main Street was as soft as a yoga mat. Two-inch headlines announced the event as though it were a victory at sea. A few months later, when a school friend told me that kids our age were being hired to sell Disneyland guidebooks on weekends and in the summer, I couldn’t wait. I pedaled my bicycle the two miles to Disneyland, parked it in the bike rack—locks were unnecessary—and looked up to see a locomotive from yesteryear, its whistle blowing loudly and its smokestack filling the air with white steam, chugging into the turn-of-the-century depot just above a giant image of Mickey Mouse rendered in vibrantly colored flowers. I went to the exit, told a hand-stamper that I was applying for a job, and was directed toward a souvenir stand a few steps inside the main gate. I spoke with a cigar-chomping vendor named Joe and told him my résumé: no experience at anything. This must have impressed Joe, because I was issued a candy-striped shirt, a garter for my sleeve, a vest with a watch pocket, a straw boater hat, and a stack of guidebooks to be sold for twenty-five cents each, from which I was to receive the enormous sum of two cents per book. The two dollars in cash I earned that day made me feel like a millionaire.

Guidebooks were sold only in the morning, when thousands of people poured through the gates. By noon I was done, but I didn’t have to leave. I had free admission to the park. I roamed through the Penny Arcade, watched the Disneyland Band as they marched around the plaza, and even found an “A” ticket in the street, allowing me to choose between the green-and-gold-painted streetcar or the surrey ride up Main Street. Because I wisely kept on my little outfit, signifying that I was an official employee, and maybe because of the look of longing on my face, I was given a free ride on the Tomorrowland rocket to the moon, which blasted me into the cosmos. I passed by Mr. Toad and Peter Pan rides, toured pirate ships and Western forts. Disneyland, and the idea of it, seemed so glorious that I believed it should be in some faraway, impossible-to-visit Shangri-la, not two miles from the house where I was about to grow up. With its pale blue castle flying pennants emblazoned with a made-up Disney family crest, its precise gardens and horse-drawn carriages maintained to jewel-box perfection, Disneyland was my Versailles.

I became a regular employee, age ten. I blazed shortcuts through Disneyland’s maze of pathways, finding the most direct route from the Chicken of the Sea pirate ship to the Autopia, or the back way to Adventureland from Main Street. I learned speed-walking, and I could slip like a water moccasin through dense throngs of people, a technique I still use at airports and on the sidewalks of Manhattan. Though my mother provided fifty cents for lunch (the Carnation lunch counter offered a grilled cheese sandwich for thirty-five cents and a large cherry phosphate with a genuine red-dye-number-two cherry for fifteen cents), the big difference in my life was that I was self-reliant and funded. I was so proud to be employed that some years later—still at Disneyland—I harbored a secret sense of superiority over my teenage peers who had suntans, because I knew it meant they weren’t working.

In Frontierland, I was fascinated by a true cowboy named Eddie Adamek, who twirled lariats and pitched his homemade product, a prefab lasso that enabled youngsters to make perfect circles just like their cowboy heroes. Eddie, I discerned, was living with a woman not his wife, the 1955 equivalent of devil worship. But I didn’t mind, because his patronage enabled me to learn rope tricks, including the Butterfly, Threading the Needle, and the Skip-Step. A few years later, after my tenure as guidebook salesman ended—perhaps at thirteen I was too old—I became Eddie’s trick-rope demonstrator, fitting in as much work as I could around my C-average high school studies.

In my mapping of the Disney territory, two places captivated me. One was Merlin’s Magic Shop, just inside the Fantasyland castle gate, where a young and funny magician named Jim Barlow sold and demonstrated magic tricks. The other was Pepsi-Cola’s Golden Horseshoe Revue in Frontierland, where Wally Boag, the first comedian I ever saw in person, plied a hilarious trade of gags and offbeat skills such as gun twirling and balloon animals, and brought the house down when he turned his wig around backward. He wowed every audience every time.

The theater, built with Disneyland’s dedication to craftsmanship, had a horseshoe-shaped interior adorned with lush gay-nineties decor. Oak tables and chairs crowded the saloon’s main floor, and a spectacular mirrored bar with a gleaming foot rail ran along one side. Polished brass lamps with real flames gave off an orangey glow, and on the stage hung a plush golden curtain tied back with a thickly woven cord. A balcony lined with steers’ horns looped around the interior, and customers dangled their arms and heads over the railing during the show. Four theater boxes stood on either side of the stage, where VIPs would be seated ceremoniously behind a velvet rope. Young girls in low-cut dance-hall dresses served paper cups brimming with Pepsi that seemed to have an exceptionally stinging carbonated fizz, and the three-piece band made the theater jump with liveliness. In the summer the powerful air-conditioning made it a welcome icebox.

The admission price, always free to everyone, made me a regular. Here I had my first lessons in performing, though I never was on the stage. I absorbed Wally Boag’s timing, saying his next line in my head (“When they operated on Father, they opened Mother’s male”), and took the audience’s response as though it were mine. I studied where the big laughs were, learned how Wally got the small ones, and saw tiny nuances that kept the thing alive between lines. Wally shone in these performances, and in my first shows, I tried to imitate his amiable casualness. My fantasy was that one day Wally would be sick with the flu, and a desperate stage manager would come out and ask the audience if there was an adolescent boy who could possibly fill in.

Merlin’s Magic Shop was the next best thing to the cheering audiences at the Golden Horseshoe. Tricks were demonstrated in front of crowds of two or three people, and twenty-year-old Jim Barlow took the concept of a joke shop far beyond what the Disney brass would have officially allowed, except it was clear that the customers enjoyed his kidding. Coiled springs of snakes shot out of fake peanut-brittle cans, attacking the unsuspecting customer who walked through the door. Jim’s greeting to browsers was, “Can I take your money—I mean help you?” After a sale, he would say loudly, “This trick is guaranteed!…to break before you get home.” Like Wally, Jim was genuinely funny, and his broad smile and innocent blond flattop smoothed the way for his prankster style. I loitered in the shop so often that Jim and I became buddies as I memorized his routines, and I wanted more than ever to be a magician.

The paraphernalia sold in the magic store was exotic, and I was dazzled by the tricks’ secret mechanics. The Sucker Die Box, with its tricky false fronts and gimmicked door pulls, thrilled me. At home, I would peruse magic catalogs for hours. I was spellbound by the graphics of another era, unchanged since the thirties, of tubes that produced silks, water bowls that poured endlessly, and magic wands that did nothing. I dreamed of owning color-changing scarves and amazing swords that could spear the selected card when the deck was thrown into the air. I read advertising pamphlets from distant companies in Ohio that offered collapsible opera hats, pre-owned tuxedos, and white-tipped canes. I had fantasies of levitation and awesome power and, with no Harry Potter to be compared to, my store-bought tricks could go a long way toward making me feel special. With any spare money I had, I bought tricks, memorized their accompanying standard patter, and assembled a magic show that I would perform for anyone who would watch, mostly my parents and their tolerant bridge partners.

One afternoon I was in the audience at the Golden Horseshoe, sipping my Pepsi and mouthing along with Wally Boag, when I blacked out and collapsed. I remember my head striking the table. A few seconds later, I was sitting back up but unnerved. Nobody noticed, but I reported this incident to my mother, and she called Dr. Kusnitz, perhaps Orange County’s only Jewish doctor, who lived next door. “What was it?” he asked. “It was a thump in my chest,” I said. Tests confirmed I had a heart murmur, more spookily expressed as a prolapsed mitral valve, a mostly benign malady that was predicted to go away as I aged. It did, but it planted in me a seed of hypochondria that poisonously bloomed years later.

I loved my derby hat and cane, both purchased by mail.

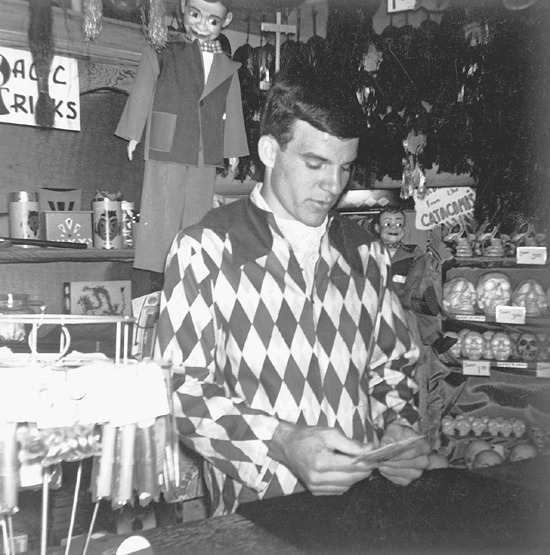

After poor sales ended my trick-roping days, I spent a year working away from the action, in the sheet-metal-gray storage room of Tiki’s Tropical Imports in Adventureland, where I pinned finger-piercing price tags onto straw hats (I’m sure my bloody screams alarmed the nearby dock loaders). On my infrequent trips to the actual store, I was entertained by a vibrant Biloxi-born store manager named Irene, who, I now realize, was probably the first neurotic I ever met. Her favorite saying—“Well, excuse me for livin’!”—stuck in my head. I had heard rumors of a job opening up at the magic shop, and longing to be free of the sunless warehouse, I went over and successfully applied, making that day the happiest of my life so far. I began my show business career a few days later, at age fifteen, in August 1960. I stood behind a counter eight hours a day, shuffling Svengali decks, manipulating Wizard decks and Mental Photography cards, and performing the Cups and Balls trick on a rectangle of padded green felt. A few customers would gather, usually a young couple on a date, or a mom and dad with kids. I tried my first jokes—all lifted from Jim’s funny patter—and had my first audience that wasn’t friends or family. My weekends and holidays were now spent in long hours at Disneyland, made possible by lax child labor laws and my high school, which assigned no homework. At closing time, I would stock the shelves, sweep the floor, count out the register, and then bicycle home in the dark.

At the magic shop.

The magic shop purveyed such goodies as the arrow-through-the-head and nose glasses, props I turned into professional assets later on. Posted behind the scenes, too risqué for Disneyland’s tourists, was a little gag postcard that had been printed in Japan. It said, “Happy Feet,” and featured the outline of the bottoms of four feet, two pointed up, two pointed down. After I studied it for about an hour, Jim Barlow explained that it was the long-end view of a couple making love.

There were two magic shops—the other was on Main Street—and I ran between them as necessary. In the Main Street store, there was a booth, really an alcove, where you could get your name printed in a headline, WANTED, HORSE THIEF, YOUR NAME HERE, and I mastered the soon-to-be-useless art of hand typesetting. The proprietor, Jim—a different Jim—laughed at me because I insisted on wearing gardening gloves while I worked with the printing press. I couldn’t let the ink stain my hands; it would look unsightly when I was demonstrating cards. At the print shop I learned my first life lesson. One day I was particularly gloomy, and Jim asked me what the matter was. I told him my high school girlfriend (for all of two weeks) had broken up with me. He said, “Oh, that’ll happen a lot.” The knowledge that this horrid grief was simply a part of life’s routine cheered me up almost instantly.

Merlin’s was run by Leo Behnke, a fine card and coin manipulator who was the first person to let me in on the inner secrets of magic, and who endorsed a strict code of practice and discipline that I took to heart. But Leo had another quality that transfixed me. He handled cards with delicacy; there was a rhythm to his movements that was mildly hypnotic. He could shuffle the deck without ever lifting it from the tabletop: After an almost invisible riffle, every card was interlaced exactly with the next, a perfect shuffle. Then, with the elegance of Fred Astaire, he squared the cards by running his fingers smoothly around the edges of the deck. Leo taught me his perfect shuffle (called the faro shuffle), which I perfected a mere four months later, and I squared the deck just like he did. I enjoyed making the sleights imperceptible and moving my fingers around the cards with Leo’s grace and ease. A magician’s hands are often hiding things, and I learned that stillness can be as deceptive as motion. It was my first experience with the pleasure and subtlety of physical expression, and I became aware of the potency of movement.

Because I was demonstrating tricks eight to twelve hours a day, I got better and better. I could even duplicate the effects of trick decks with a regular deck. I was able to afford more professional equipment, including, at a price of four dollars and fifty cents, the Zombie, a floating silver ball that danced behind a silk scarf to bewildering effect. I put together a magic act, complete with music, that required a friend to put the needle down on a record at exactly the right moment, in exactly the right groove. Jim Barlow connected me to a network of desperate Cub Scout troops seeking entertainment, and the minuscule prestige from my magic shop gig enabled me to work for free or sometimes for five dollars at the local Kiwanis Club. I was now performing at the hectic pace of one show every two or three months. Later in life, I wondered why the Kiwanis Club or the Rotary Club, comprised of grown men, would hire a fifteen-year-old boy magician to entertain at their dinners. Only one answer makes sense: out of the goodness of their hearts.

Claude Plum, a suspender-wearing oddnik who, among other things, collected thousands of B-movie stills from the 1940s, wrote a mimeographed in-house newsletter for Disneyland and supplied gags for Wally Boag: “I’m in the dark side of the cattle business.” “Do you rustle?” “Only when I wear taffeta shorts.” He would lend me his copies of Robert Orben’s joke books, filled with musty one-liners from other comedians’ acts, but to me they were as new as sunrise. These books were like the Bible and I scoured them for usable passages. For five dollars, a major investment, I hired Claude to write some material for my floating silver ball routine: “With the advent of the space age,” I squeaked, “scientists have been searching for a metal that can defy gravity…. ”

Performing for Cub Scouts.

The magic shop put me in daily contact with people, and when I was fifteen, there was only one kind of people: girls. I have a clear memory of standing behind the counter watching a girl in shorts turn away from me, and being confronted by the alarmingly pleasant sight of her rear end and all its curvy virtues. My body flooded with chemistry, and the female behind was instantly added to my growing list of turn-ons, which up till then included only faces, hair, and that which I will call brassieres, because actual breasts were still unseen and never experienced. The Main Street store was run by Aldini the Magician—real name Alex Weiner—a mustachioed, tart-tongued spiel-meister who taught me all the Yiddish words I know, including the invaluable tuchis (meaning “ass”), which he used as a code word to indicate that a sexy girl had come into the shop.

I did have a life outside Disneyland. I had been attending Rancho Alamitos High School, but in the fall of 1962, redistricting moved me across town to Garden Grove High School, where I was happy to discard my old personality and adopt a new one defined by the word of the day, “nonconformist.” Of course, the difference between my old personality and my new personality was probably imperceptible, so I was lucky to have all-new classmates who would not remember my old conformist ways.

On my first day of school, the student body was called together for an assembly, and this was when I saw the face of God. The Don Wash Auditorium seated fifteen hundred people, and its interior narrowed like a funnel to focus all eyes on its polished hardwood stage. The proscenium was framed by heavy velvet curtains, and the acoustics were—and still are—brilliant and sharp, making microphones unnecessary. I sat in the audience, looking up at the stage, surrounded by high-energy, adolescent chatter. The house lights dimmed dramatically, and when the crisp ice-blue spotlight illuminated center stage in anticipation of parting curtains and grand entrances, I knew I wanted to be up there rather than down here.

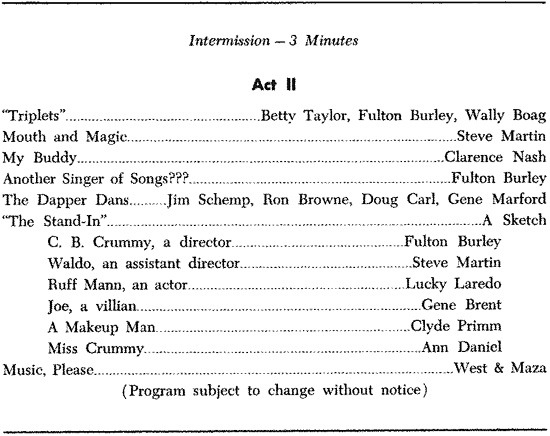

When Claude Plum asked me to appear in a vaudeville show featuring Wally Boag, coincidentally staged at this auditorium, my heart leaped. I was to perform a five-minute act, billed as “Steve Martin: Youth and Magic,” in an evening show for Wally’s fans. The programs appeared from the printer with the perfect prescient typo: “Steve Martin: Mouth and Magic.” I couldn’t judge how it went, since it was my first show in front of a sizable audience, but I don’t remember a standing ovation. Claude Plum appeared in the program, too, but he listed his name as Clyde Primm in order to escape creditors. Years later, I ran into him working at Larry Edmunds’s rare-book store on Hollywood Boulevard. Claude was still weird and mysterious, a bit of a pigpen, still with a one-inch stub of smoldering cigarette pursed in his lips, still collecting artifacts of forties film noir.

The daily excitement of my life at Disneyland and high school was in stark contrast to my life at home. Silent family dinners, the general taboo on free talk and opinion, my father’s unpredictable temper, and the stubborn grudges I collected and held toward him meant that the family never gelled. But when I was away from home, my high school pals and I enjoyed endless conversation and laughter, and my enthusiasm for what I was doing—working at Disneyland, clowning with friends, and being swept up in the early rock and roll of AM radio—made life seem joyful and limitless. When I moved out of the house at eighteen, I rarely called home to check up on my parents or tell them how I was doing. Why? The answer shocks me as I write it: I didn’t know I was supposed to.

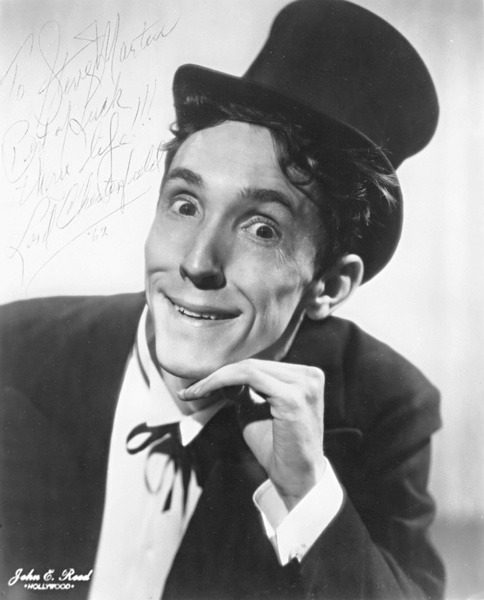

THINGS WERE CHANGING at the magic shop. Leo Behnke left to consult on a television show, and our store needed a new manager. Leo’s replacement was a fortunate choice for me. Dave Steward, emaciated, lanky, and deadpan, was an actual former vaudevillian who had worked the circuits with a magic act. He went by the name Lord Chesterfield, later changed to David and Company because, he said, the “company” implied two people, and he could ask for more money. His act had been that of a stone-faced, bungling magician, which appealed to me because Jim Barlow’s and my hero at the time was the king of bungling magicians, Carl Ballantine, whose legendary appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show nudged every young magician toward comedy.

Dave Steward’s vaudeville act had involved an ordinary-looking violin that he was always about to play but never did. His big finish, enabled by old-world craftsmanship, was its instantaneous transformation into a bouquet of flowers. One day he brought his trick violin to the store to share with this sixteen-year-old boy. He flicked a hidden switch, and I watched as the violin changed into a colorful bouquet of feather-flowers. Nice, but then he showed me his opening joke: He walked from behind the counter and stood on the floor of the magic shop, announcing, “And now, the glove into dove trick!” He threw a white magician’s glove into the air. It hit the floor and lay there. He stared at it and then went on to the next trick. It was the first time I had ever seen laughter created out of absence. I found this gag so funny that I asked permission to use it in my youthful magic act, and he said yes.

Dave Steward’s vaudeville publicity photo.

He told me another bit. He would take out a white handkerchief, pretend to mop his brow, and then, thanks to a rubber ball sewn into the cloth, absentmindedly bounce it on the floor. I didn’t really get the joke, but the concept stuck. I took a high-bounce juggling ball and sewed it inside a realistic-looking cloth rabbit. Producing the bunny from a tube painted with Chinese symbols, I would say, “And now, a live bouncing baby rabbit!” Then, to everyone’s shock and eventual laughter, I would bounce the rabbit on the floor. I had my first original gag.

Dave Steward’s stories intrigued me, and I developed an interest in the history of vaudeville. I read up on the subject, studying Joe Laurie’s book Vaudeville, and was captivated by its descriptions of each old-time act. It mentioned the Cherry Sisters, and it was here that I first heard an act described as “so bad it was good.” The five screeching sisters elicited boos and vegetables from the audience and yet still made it to Broadway, a concept that the off-pitch singer Mrs. Miller succeeded with in the sixties and that Andy Kaufman took to the limit in the eighties. My interests widened to carnival scams, thanks to the nearby Long Beach Pike and its boardwalk games and sideshow featuring Zuzu the Monkey Girl; Electra (a woman who could light lightbulbs in her bare hand); and a two-headed baby resting in formaldehyde that was actually a convincing rubber facsimile. There was also a roller coaster called the Cyclone Racer, whose behemoth wooden skeleton extended out over the sea. I was hoping the carnies would let me in on their secrets, but they never did. Maybe it was my Ivy League button-down shirts that kept them from thinking I was one of them.

The Main Street shop sold magic books. Rarely purchased, they gathered dust on a high shelf. A yellow cover caught my eye, and this book turned out to be more important to me than The Catcher in the Rye. It was Dariel Fitzkee’s Showmanship for Magicians, first published in 1943. A terse Internet bio of Mr. Fitzkee (who turned out, coincidentally, to be a distant relative by marriage) describes him this way:

Born in Annawan, Illinois. Pen name of Dariel Fitzroy.

Acoustical engineer in San Rafael, California. Semi-pro

magician. Toured an unsuccessful full-evening show

1939–40. Reportedly dropped magic in disgust.

Showmanship for Magicians is a handbook meant to turn amateurs into professionals. Its subtitle is Complete Discussions of Audience Appeals and Fundamentals of Showmanship and Presentation. I held my first copy and solemnly turned the pages, reading each sentence so slowly that it’s a miracle I could remember what the verb was. The cover was plain-faced—like a secret manifesto that should be hidden under your mattress—and the pages were as thick as rags. Fitzkee starts by denigrating the current state of magic, saying it is old-fashioned. Though published in 1943, this statement contains an enduring truth. All entertainment is or is about to become old-fashioned. There is room, he implies, for something new. To a young performer, this is a relief. My references were all in the past, and in just one chapter, these roots were severed, or at least choked. Fitzkee then goes on to break down a show into elements such as Music, Rhythm, Comedy, Sex Appeal, Personality, and Selling Yourself, and he concludes that attention to each is vital and necessary. Why not throw everything in the book at the audience, like an opera does? Costumes, lights, music, everything? He also talks about something that was to land on me with a thud six years later: the importance of originality. “So what,” I thought at the time. “Who cares?”

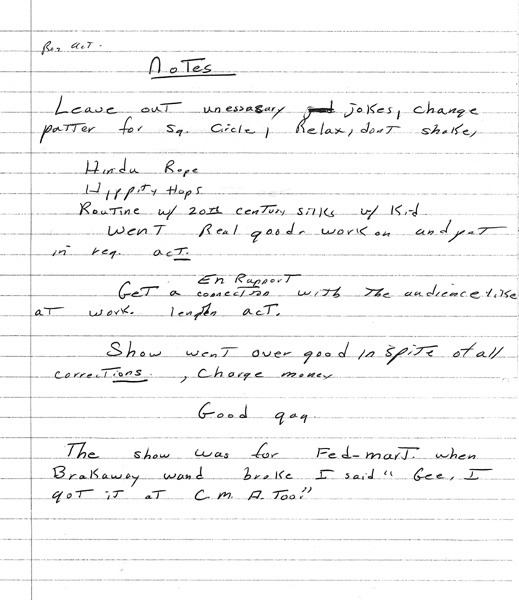

Following the advice in Showmanship for Magicians, I kept scrupulous records of how each gag played after my local shows for the Cub Scouts or Kiwanis Club. “Excellent!” or “Big laugh!” or “Quiet,” I would write in the margins of my Big Indian tablet; then I would summarize how I could make the show better next time. I was still motivated to do a magic show with standard patter, but the nice response to a few gags had planted a nagging thought that contradicted my magical goal: They love it when the tricks don’t work. I started to think that the future of a serious magician was limited. Plus, I was priced out of the market by the impossible cost of advanced stage illusions: Sawing a Lady in Half, two hundred dollars. By doing comedy, however, I could be more like Stan Laurel and Jack Benny, more like Wally Boag. I was still using Claude’s somber introduction to my floating silver ball routine, but I added a twist at the end of the long-winded speech: “And now, ladies and gentlemen, the toilet float trick.”

My performing notes, from age fifteen, complete with misspellings.

My time at the magic shop gave me a taste of performing and convinced me that I never wanted to wait on customers again. I didn’t have the patience; my smile was becoming plastered on. I then crossed all kinds of jobs off my list of potentials, such as waiting tables or working in stores or driving trucks: How could my delicate fingertips, now dedicated to the swift execution of the Two-handed Pass, clutch the heavy, callus-inducing steering wheel of a ten-ton semi?

But there was a problem. At age eighteen, I had absolutely no gifts. I could not sing or dance, and the only acting I did was really just shouting. Thankfully, perseverance is a great substitute for talent. Having been motivated by Earl Scruggs’s rendition of “Foggy Mountain Breakdown,” I had learned, barely, to play the banjo. I had taught myself by slowing down banjo records on my turntable and picking out the songs note by note, with a helpful assist from my high school friend John McEuen, already an accomplished player. The only place to practice without agonizing everyone in the house was in my car, parked on the street with the windows rolled up, even in the middle of August. Also, I could juggle passably, a feat I had learned from the talented Fantasyland court jester Christopher Fair (who could juggle five balls while riding a high unicycle) and which I practiced in my backyard using heavy wooden croquet balls that would clack against each other, pinching my swollen fingers in between. Despite a lack of natural ability, I did have the one element necessary to all early creativity: naïveté, that fabulous quality that keeps you from knowing just how unsuited you are for what you are about to do.

After high school graduation, I halfheartedly applied to and was accepted at Santa Ana Junior College, where I took drama classes and pursued an unexpected interest in English poetry from Donne to Eliot. I had heard about a theater at Disneyland’s friendly, striving rival, Knott’s Berry Farm, that needed entertainers with short acts. One afternoon I successfully auditioned with my thin magic act at a small theater on the grounds, making this the second happiest day of my life so far.

My final day at the magic shop, I stood behind the counter where I had pitched Svengali decks and the Incredible Shrinking Die, and I felt an emotional contradiction: nostalgia for the present. Somehow, even though I had stopped working only minutes earlier, my future fondness for the store was clear, and I experienced a sadness like that of looking at a photo of an old, favorite pooch. It was dusk by the time I left the shop, and I was redirected by a security guard who explained that a photographer was taking a picture and would I please use the side exit. I did, and saw a small, thin woman with hacked brown hair aim her large-format camera directly at the dramatically lit castle, where white swans floated in the moat underneath the functioning drawbridge. Almost forty years later, when I was in my early fifties, I purchased that photo as a collectible, and it still hangs in my house. The photographer, it turned out, was Diane Arbus. I try to square the photo’s breathtakingly romantic image with the rest of her extreme subject matter, and I assume she saw this facsimile of a castle as though it were a kitsch roadside statue of Paul Bunyan. Or perhaps she saw it as I did: beautiful.