Breakthrough

I DID HAVE A TINY BIT of drawing power, generated through my daytime television appearances and my growing presence on The Tonight Show, but mostly my name was a rumor. My dubious status as a headliner led me to a tiny pie slice of a folk club in Greenwich Village, the Metro. Now I had an opening act. Still, no one showed up to see me and a new duo, Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks. I told the club owner that he could let me go if he wanted, that I wouldn’t hold him to his contract. He said he wanted me to stay…until the next night, when again no one showed up. We parted with a handshake.

In March 1975 my agent, Marty Klein, secured a job in San Francisco, two weeks headlining the Playboy Club for fifteen hundred dollars per week. A big payday, and I was desperate for money. Playboy Clubs always made me nervous. I never seemed to do well in them, but I had no choice. Opening night was on a Monday, which was already unusual; clubs were usually closed on Mondays. I stood at the back of the club and checked out the capacity crowd. Amazed, I said to one of the musicians leaning against the wall, “We got a nice house out there.” An odd look crossed the musician’s face. “Yeah,” he said mysteriously.

After I was introduced as Steve Miller, I walked out onstage and saw a sea of Japanese faces. I attempted a few lines; nothing came back except nice smiles. No one spoke English. It turned out that the bus tours offered a nightclub as part of their packages, but on Mondays the Playboy Club was the only one open, so every foreign tour group was herded into this showroom. Now I understood the musician’s wry grin. I gamely went forward, not doing badly because the audience was kind and polite, and my balloon-animal and magic act went over well because it was visual and antic. The next night I went on for the regular audience: death. Comedy Death. Which is worse than regular death. I sank low and, in spite of my declining financial situation, called Marty, saying, “You’ve got to get me out of here.” He did, and I went back the next night to collect my things. My clothes had been stolen. A week later, I took out a bank loan of five thousand dollars.

The euphoria from my week at Bubbas in Coconut Grove and my nice score on The Tonight Show had dissipated, and I was marooned in the depression that followed my flop at the Playboy Club. In June 1975 I was booked into the frighteningly named Hub Pub Club, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The Hub Pub Club, located in a shopping mall, was trying to be a fancy spot for gentlemen, but the liquor laws in North Carolina limited attendance at nightclubs to members only. About the worst things an entertainer can hear are “members only” and “group tours.” While I was onstage doing my act to churchlike silence, a guy said to his date, loud enough that we all heard it, “I don’t understand any of this.” And at that moment, neither did I.

In spite of the gloom, I had a premonition of success, and in January 1975 I started a short-lived diary. It surprises me that a diary meant to chronicle an important year in my life could contain so many negative passages. My entry for the Hub Pub Club started this way: “This town smells like a cigarette.” Then I sank a bit lower: “My material seems so old. The audience indulged me during the second show.” Then I really started wallowing in it: “My act might have well been in a foreign language…my act has no ending.” Next I degenerated into my version of Kurtz’s lament, “The horror, the horror,” from Heart of Darkness: “My new material is hopelessly poor. My act is simply not good enough—it’s not even bad.”

However, there was one, sole, positive entry in my journal that week. It related to a lonely-guy phone call I had made to a new acquaintance, Victoria Dailey. Victoria was a young rare-book-and-print dealer in Los Angeles whom I had stumbled upon in my collecting quests, and who had her wits about her in the same way that Oscar Wilde had his wits about him. I must have had an intuition about the future depth and scope of our relationship, as I called her long distance from a motel phone, which in those days cost about a million dollars a minute. While traffic whizzed by outside the gray motel room, I churned out my Winston-Salem stories with the same toxicity as the R. J. Reynolds company churned out cigarettes. Victoria used her refined sense of artistic ethics to talk me down from my metaphorical window ledge, and over the next few years we cemented an enduring relationship that has been complex and rewarding. We have been connected over the past thirty years intellectually, aesthetically, and seemingly, gravitationally. In my latest conversation with her, I complimented her recent essay on early Southern California history. I said, “Do you realize you’re going to be studied one day?” She replied, “Only one day?”

Two months after Winston-Salem everything was about to change. A few blocks away from San Francisco’s Playboy Club, where I had died so swiftly, was a very different kind of club, one that booked current music acts, and where the waitresses were sexy but didn’t have to wear bunny outfits. I had played the Boarding House before, but only as a developing opening act. The owner, David Allen, saw that things were different, both with my act and with its reception, and he was ready to try the new and improved me. In August 1975 I was booked to headline, evidence that the Boarding House and the Playboy Club did not speak to each other. My years on the road had produced a change I had only dreamed of earlier: I now had four hours of material from which to pick and choose, and there was more to come.

I opened at the Boarding House on a Tuesday evening to a fair-sized crowd. Headlining there, in friendly and familiar San Francisco, where I had established some kind of beachhead, filled me and the audience with confidence. They had paid to see this show, this particular show, and I was inspired to push the limits even further. What had been deadly at the Playboy Clubs was lively with a younger crowd. I wanted the audience to leave with the feeling that something had happened. The first few minutes into the show, I began to strum the banjo, singing a song that had no particular tune or rhyme:

We’re having some fun

We’ve got music and laughter

And wonderful times

That’s so important in today’s world

Oh yeah.

It’s so hard to laugh

It seems that short of tripping a nun

Nothing is funny anymore

But you know

I see people going to college

For fourteen years

Studying to be doctors and lawyers

And I see people going to work

At the drugstore at 7:30 every morning

To sell Flair pens

Onstage at the Boarding House.

But the most amazing thing to me is

I get paid

For doing

This.

Midweek, before the show, I told the spotlight operator not to change the light no matter how urgently I asked him to do it. Then, onstage, I made a small request for some mood lighting, a blue spotlight. The light stayed white. I slowly grew more and more angry. “Please,” I said, “I would really like a blue spot. It’s for the mood-lighting thing.” I got very serious and murmured under my breath, “I can’t even get a light change.” John McEuen was sitting in the light booth that night. He said the operator began to believe me and moved to change the spot, but John stopped him. Soon it became clear that it was a gag, because I was reaching new levels of anger as I said how disgusting it was “that I, this entertainer who keeps giving, and giving and giving, and keeps on giving, can’t seem to get a simple blue spotlight!” The bit ended at an exaggerated level of madness, with me screaming another phrase from my past, “Well, excuuuse me,” turning four syllables into about twenty. The audience response was nice enough, but I was surprised weeks later when I heard this expression coming back to me on the streets. It surprised me even more when in another few years it became a ubiquitous catchphrase.

Toward the end of the Boarding House show, I stepped off the stage, saying: “I just want to come down into the audience with my people…DON’T TOUCH ME!” I took them into the lobby, where there was an old-fashioned grand staircase. One of the doormen, a very likable and funny guy named Larry who had seen my show all week, happened to come in from the street, carrying a pair of pants on a hanger fresh from the dry cleaner. I looked at him, and he looked back, knowing he was in for it. He had a great sense of humor and didn’t mind a bit. I said disdainfully, “Oh, it’s Cleanpants. Mr. Cleanpants. You think your pants are so CLEAN. Well, CLEANPANTS, we don’t need your type around here…. WAIT, CLEANPANTS…where ya going? You think you don’t need us because your PANTS ARE SO CLEAN?” A better comic foil could not have been found; I still can see Larry standing there holding his dry cleaning and accepting the fake lambasting with bemused patience. And the audience, crowded together in the stairwell and mezzanine, ate it up.

MY SISTER, MELINDA, had gotten married and was raising her two children in San Jose, an hour’s drive from San Francisco. My communication with her over the past decade had been minimal. She had made efforts to connect, but my travel kept sweeping me away, and I was most comfortable in the world I had made, detached from home ties. When I first became an uncle, I could have used a self-help book, So Now You’re an Uncle. Melinda showed up at one of these Boarding House performances, and we visited after the show. It turned out she had been proudly monitoring my career from a distance, saving reviews and magazine stories, but our relationship, because of my familial ineptness, remained awkward and was not yet ready to bloom.

Bill McEuen dragged his Nagra up to San Francisco and started taping my shows in hopes of crafting a record from the material. John Wasserman, the critic at the San Francisco Chronicle, offered a rave of the Boarding House appearance that was so enticing it made me want to see the show. At the end of the week, I was handed my percentage of the gate, an envelope containing forty-five hundred dollars in cash, a sum I had never seen in one place before, much less in my needy and greedy palm. I walked home in the dark toward my room at the Hotel Commodore—still lugging my banjo, which I never let out of my sight—and fortunately, I was not mugged. There was something about that walk in the night that recalled my contemplative mood of nine years earlier, when I sat in darkness, just a few miles away at the Coffee Gallery, with absolutely no prospects. But now I was about to enter a phase of my life when three things would occur: I would earn money; I would grow to be famous; and I would be the funniest I ever was.

AFTER THE BOARDING HOUSE GIG, I was booked into a club in Nashville called the Exit/In. It was a lowceilinged box, painted black inside, with two noisy smoke eaters hanging from the ceiling, to no avail. The dense secondhand smoke was being inhaled and exhaled, making it thirdhand and fourthhand smoke. The stage was perfectly situated in the corner of the room.

When I was performing, I could touch the ceiling with my hand, and I had to be careful when jumping onstage not to knock myself out. I was selling tickets without the usual requirement of hit records. The audience was there by word of mouth only, so everything they saw me do was new. The room seated about two hundred and fifty, and the shows were oversold, riotous and packed tight, which verified a growing belief of mine about comedy: The more physically uncomfortable the audience, the bigger the laughs. I continued closing the show by performing outside, which had an auxiliary effect of emptying out the house so the second show could begin. One night at the Exit/In I took the crowd down the street to a McDonald’s and ordered three hundred hamburgers to go, then quickly changed it to one bag of fries. Another night, I took them to a club across the street and we watched another act. I was a new-enough performer that there was no overblown celebrity worship, which meant I could do the show and carouse in the streets, uninterrupted by ill-timed requests for autographs or photos. Even though I had done the act hundreds of times, it became new to me this hot, muggy week in Nashville. The disparate elements I’d begun with ten years before had become unified; my road experience had made me tough as steel, and I had total command of my material. But most important, I felt really, really funny.

I MOVED TO ASPEN, COLORADO, to be closer to my pals Bill McEuen and the Dirt Band. It was there, on the night of October 11, 1975, that I turned on the TV and watched the premier episode of Saturday Night Live. “Fuck,” I thought, “they did it.” The new comedy had been brought to the airwaves in New York by people I didn’t know, and they were incredibly good at it, too. The show was a heavy blow to my inner belief that I alone was leading the cavalry and carrying the new comedy flag. Saturday Night Live and I, however, were destined to meet.

My performing roll continued. Dave Felton, a highly regarded rock-and-roll journalist, interviewed me for an article in Rolling Stone. He did a perceptive job of quoting my act verbatim, using pauses, italics, and sudden jumps into all capital letters. It read funny, even the visual stuff, and rather than kill the act through exposure, he made it a necessity to see in person. Felton wrote, “This isn’t comedy; it’s campfire recreation for the bent at heart. It’s a laugh-along for loonies. Disneyland on acid.” On the strength of everything that was happening, Bill McEuen closed a record deal with an uneasy Warner Bros. He took the Boarding House recordings up to his studio in Aspen and began editing them.

I was still adding to the show. My Ramblin’ Guy persona had been inspired, way back, by the folksinger Ramblin’ Jack Elliott’s outlaw stance, then reinforced by the Allman Brothers’ hit “Ramblin’ Man” and even Joni Mitchell’s “He’s a rambler and a gambler and a sweet-talkin’ ladies man.” It seemed like all the sexy guys were ramblers! I would sing: “I’M RA-uh-AM-uh-AM-uh-AM…[long pause]…BLIN’!” I liked to give myself heroic qualities that were obviously delusional. I started saying with mock self-importance, “I’m so wild.” Then “I’m a wild and crazy guy.” Which actually was a bailout if a bit didn’t work. The piece developed into this: “Yes…I am…a wild and craaaazy guy…the kind of guy who might like to do annnaything…at any time…to drink champagne at three A.M. or maybe…at four A.M…. eat a live chipmunk…or maybe even…[excitedly]…WEAR TWO SOCKS ON ONE FOOT.”

Forces converged. The article in Rolling Stone, my live performances, appearances on The Tonight Show, a modestly produced one-man show on the new and experimental network HBO, and intriguing reviews and press made audiences ignite. The confluence that I had doubted would ever happen through auditions for sitcoms was now happening outside of Hollywood’s control. My audience was developing more like a rock-and-roll band’s than a comedian’s: I was underground and on the road.

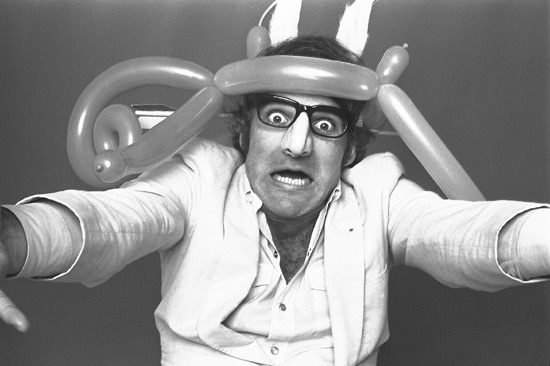

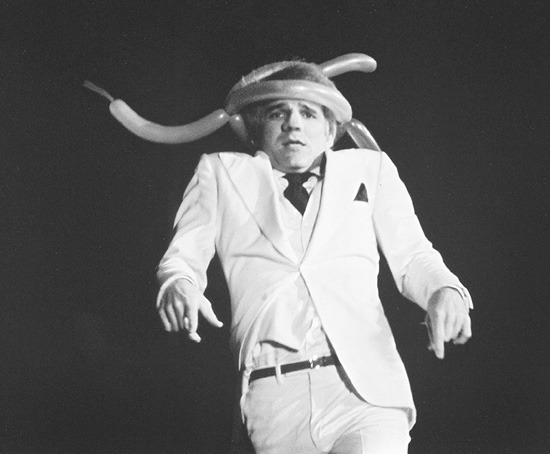

Outside of the big cities, I was playing concerts seating about five hundred people, a small number, but they were avid. Aggressive fans, sometimes wearing arrows through their heads or balloon hats, were gathering outside the stage door after the shows, and I had to have a guard walk me safely to my car. After a show at a college in Boise, Idaho, I said to the two student escorts, “Stand close, I’ll sign a few autographs, but we should keep moving toward the car.” I pushed open the stage door. A rush of Idaho silence. Nobody. Nothing but twinkling stars. Idaho hadn’t gotten the word yet. The two students looked at me with disgust.

Some promoters got on board and booked me into a theater in Dallas. Before the show I asked one of them, “How many people are out there?” “Two thousand,” he said. Two thousand? How could there be two thousand? That night I did my usual bit of taking people outside, but it was starting to get dangerous and difficult. First, people were standing in the streets, where they could be hit by a car. Second, only a small number of the audience could hear or see me (could Charlton Heston really have been audible when he was addressing a thousand extras?). Third, it didn’t seem as funny or direct with so many people; I reluctantly dropped it from my repertoire.

I now had the luxury of performing only one show per night, which meant that after a dozen years of two, three, and even five shows per day, I no longer had to include a weak bit in order to fill time. I cut lines that I loved but which rarely worked, such as:

“I think communication is so firsbern.”

Or:

“I’m so depressed today. I just found out this ‘death thing’ applies to me.”

And:

“I have no fear, no fear at all. I wake up, and I have no fear. I go to bed without fear. Fear, fear, fear, fear. Yes, ‘fear’ is a word that is not in my vocabulary.”

Or this weird one:

“I just found out I’m vain. I thought that song was about me.”

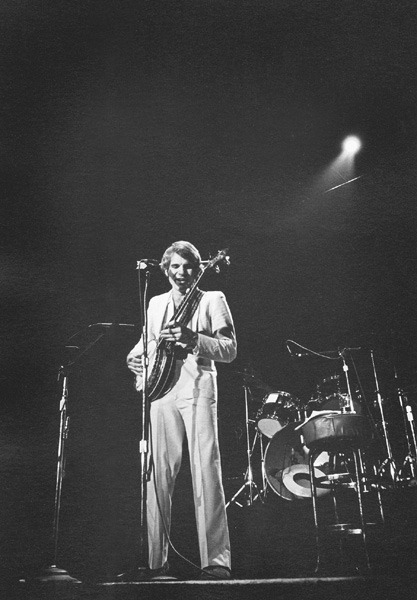

I continued doing The Tonight Show and performing in concert. Before a show in Milwaukee, I asked the promoter, “How many are out there?” Three thousand. Three thousand? It didn’t seem possible. I worried about being seen at such distances—this was a small comedy act. For visibility, I bought a white suit to wear onstage. I was conflicted because the white suit had already been used by entertainers, including John Lennon. I was afraid it might seem derivative, but I stayed with it for practical reasons, and it didn’t seem to matter to the audience or critics. The suit was made of gabardine, which always stayed fresh and flowed smoothly with my body. It got noticed in the press because it was three-piece, which appeared to be a symbol of conservatism, but I really wore the vest so my shirt would stay tucked into my pants. How could I “look better than they do” if my shirt was blousing out between my belt and my suit button? I was now coming up with jokes about the increased size of the house. My opening was the magic dime trick, in which I would claim to change the date of a dime. Then I would ask the back row what they’d paid to get in. They would shout it out, and I would laugh hysterically, implying that they were getting screwed.

Lorne Michaels, the producer of SNL, inquired about my hosting the show. Yes and yes, I said. I flew to New York a few days early, and Lorne walked me into the busy studio on Saturday afternoon. Gilda Radner’s cheery lilt and Laraine Newman’s alto voice crisscrossed as they rehearsed a sketch. Chevy Chase noodled on a piano in a corner. Danny Aykroyd and John Belushi, one a virtuoso and one a hurricane, energetically entertained each other while the cameras swung around the studio, and the dominant sound was the resonance of Danny’s big laugh. Belushi turned out to be the nicest rowdy person I ever met. Both scary and down-to-earth, he once told me, “I never yell at the staff, only the department heads.”

In Lorne’s office later that day, the leather-clad Danny Aykroyd told me he had been up all night riding his motorcycle, and when it had stalled at four A.M., he had thumbed a ride. When the car got up to speed, the driver pushed him out of the moving vehicle, and he rolled onto the rainy streets of Manhattan. I pictured Danny bouncing down the wet pavement and then said the only thing that came to mind. I asked him if he wanted to go to Saks and shop for clothes. He said, as friendly as he could, “Uh, man, that’s not my thing.” We liked each other, but we were different.

I first appeared on Saturday Night Live in October 1976. I felt powerful butterflies just prior to being introduced, especially when I reminded myself that it was live, and anything that went wrong stayed wrong. But it is possible to will confidence. My consistent performing schedule had kept me sharp; it would have been difficult to blow it. I did two monologues straight out of my act; some sketches, including Jeopardy! 1999 (remember, this was 1976); and a spoof commercial where I pitched a dog that was also a watch, called Fido-Flex. The show turned out well, though I didn’t realize how well. The next Monday I had a concert in Madison, Wisconsin. It would be my first show after the SNL appearance. “How many are out there?” I asked. Six thousand. Six thousand? At least twice the normal. I walked onstage and was greeted with a roar of such intensity that I remember feeling both pleasure and fear. In response to the deafening approval, I was, like an athlete at the college play-offs, flooded with adrenaline. I made quick adjustments for the thundering cheers and the increased audience size. I bore down. My physicality intensified and compressed—smaller gestures had greater meaning—and my comedy became more potent as I settled deeper into my own body. I opened the show with this line: “I have decided to give the greatest performance of my life! Oh, wait, sorry, that’s tomorrow night.”

My fame knocked on my parents’ door. They couldn’t help hearing about their son. My father, though, was not impressed. After my first appearance on Saturday Night Live, he wrote a bad review of me in his newsletter for the Newport Beach Association of Realtors, of which he was president: “His performance did nothing to further his career.” Later, shamefaced, my father told me that his best friend had come into his office holding the newsletter, placed it on his desk, and shaken his head sternly, indicating a wordless “This is wrong.” I believe my father didn’t like what I was doing in my work and was embarrassed by it. Perhaps he thought his friends were embarrassed by it, too, and the review was to indicate that he was not sanctioning this new comedy. Later, he gave an interview in a newspaper in which he said, “I think Saturday Night Live is the most horrible thing on television.” I suppressed anything I felt about his comments because I couldn’t let him have power over my work. After all, I explained to myself, the whole point of this comedy was to turn off the older crowd while reeling in the young. But as my career progressed, I noticed that my father remained uncomplimentary toward my comedy, and what I did about it still makes sense to me: I never discussed my work with him again.

But my mother was aglow. She had a continuing fascination with celebrities, and now she had one of her own. She was never moved by what I was doing (in an interview she said, “He writes his own material, I’m always telling him he needs a new writer”), but she was very involved with how things were going. She kept up with every little appearance and success and reported anything positive her friends had said to her, though sometimes she couldn’t discern the fine line between a compliment and an insult. After I’d started making films, she once told me, “Oh, my friends went to the movies last week end, and they couldn’t get in anywhere so they went to see yours, and they loved it!”

I was a newly minted star when we were driving through Beverly Hills and she said, “Get out and walk down the street so I can watch people look at you.” I gently declined, explaining to her how uncomfortable it would make me feel, but it never sank in. Another time she said, “I was in line at the supermarket yesterday, and when they found out I was your mother…!” I keep puzzling over the exact phraseology my proud mama must have used to work her information into normal supermarket discourse.

Money trickled her way—I was able to give her a monthly clothes allowance—and she was ecstatic. She became a regular at Neiman Marcus and loved that she was modestly famous as she browsed the racks of her favorite designer, St. John. When our mother died, my sister, Melinda, had an idea. She suggested our mother be buried on a hillside, in a plot overlooking the upscale Fashion Island shopping center in Orange County. And that is exactly what we did.

My first album, Let’s Get Small, released in 1977, sold a million and a half copies. The material was so vivid to Bill and me that we naively included bits that were largely visual. The uninitiated heard clanks and spaces that brought forth laughs, and this minus turned into a plus, as the transitions seemed more surreal than they already were. Audiences were intrigued to see live what they could only hear on the album, and the theaters filled.

During my third appearance on Saturday Night Live I incorporated a line from my act, “I’m a wild and crazy guy,” into Danny Aykroyd’s idea (along with Marilyn Miller and James Downey) about two Czechoslovakian brothers. We caught the public’s fancy, which gave me my second ticket into catchphrase heaven. My second album, A Wild and Crazy Guy, released in 1978, was being promoted every time we did the sketch on the show. It sold two and a half million copies and went to number one on the charts. Well, okay, number two. Promotion was becoming a regular part of the job, and when I did The Tonight Show it was understood that either I or Johnny would hold up an album for all to see. After A Wild and Crazy Guy blistered the record charts in 1978, I was on the cover of Rolling Stone and Newsweek.

Danny Aykroyd and me as the Czech brothers.

I hadn’t significantly collaborated with other performers since my days at the Bird Cage. My appearances on SNL, whether I was dancing with Gilda Radner, clowning with Danny, pitching show ideas with Lorne and the writers, or simply admiring Bill Murray, were community comic efforts that made me feel like I had been dropped off at a playground rather than the office. Watching the gleam in your partner’s eyes, acting on impulses that had been nurtured over thousands of shows, working with edgy comic actors—some so edgy they died from it—was thrilling. We were all united in one, single goal, which was, using the comedian’s parlance, to kill.

The record sales and the appearances on SNL compounded the size of the live audience. How many tickets sold? I asked in Toronto. “Fifteen thousand,” they said. In St. Louis, I was told, “Twenty-two thousand.” The act was on fire. My set lists from the period, now tattered and yellowed, remind me of forgotten routines: I would sing “I Can See Clearly Now” and walk into the mike. I would juggle kittens (swapping the one real kitten for a stuffed look-alike); I would stand in spilled water and touch the mike, faking an electric shock, then do it again as though I had enjoyed it. I had a long routine (for me) in which I confessed my weird sexual fetish, “I like to wear men’s underwear.”

There were more:

“I know what you’re thinking,” I would say conspiratorially, “you’re thinking, ‘Steve, how can you be so fuckin’ funny?’”

In my opening seconds, I would say, “It’s great to be here,” then move to several other spots on the stage and say, “No, it’s great to be here!” I would move again: “No, it’s great to be here!”

Shouting to the audience, “Everybody put your hands together!” I would put my hands together and hold them there, making only one clap, saying, “Now keep them together!”

“Hello, Crime Stoppers! [audience: “Hello, Steve.”] Let’s repeat the Crime Stoppers’ oath: ‘I promise not to depreciate items carried forward from one tax year as nondepreciable items!’”

“I’ve learned in comedy never to alienate the audience. Otherwise, I would be like Dimitri in La Condition Humaine.…”

“A lot of people wonder if Steve Martin is my real name. Well, I did change my name for show business. My real name is Gern Blanston. So please, just call me…[long pause]…Gern.” Don’t ask me why, but this was funny at the time. There is even a Gern Blanston website, and for a while there was a rock band that used the name.

“I’m so mad at my mother, she’s a hundred and two years old, and she called me the other day. She wanted to borrow ten dollars for some food! I said, ‘Hey, I work for a living!’”

I would stand onstage and tune my banjo, but my hand would be about a foot away from the tuners, twisting in the air. I would act as though I couldn’t figure out why it wouldn’t go in tune.

And my closer, “Well, we’ve had a good time tonight, considering we’re all going to die someday.”

Moovin’ and groovin’ onstage.

I loved performing this bit. There was a movie screen onstage, and I would go behind it and attach a fake rubber hand to it as though the hand were mine. Then I would slowly move backward, making it appear as if my arm was stretching.

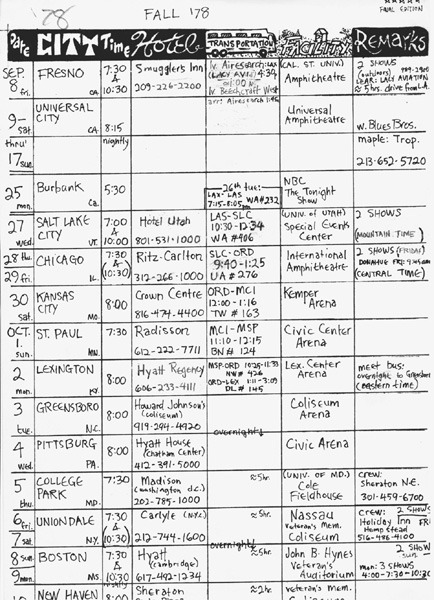

IN THE LATE SEVENTIES, I continued to tour. My schedule was this: After sleeping all night on a band bus, I would arrive at the hotel around seven A.M. and collapse in a groggy half-sleep until four P.M. Then I would have a room-service dinner, and the only thing on the hotel menu that fit my fish-a-tarian diet was breaded fried shrimp with the texture of sandpaper, really just a ketchup delivery system. Following that, I would dumbly watch the five-thirty P.M. airing of The Brady Bunch (this showing, it seemed, was universal), then I would do the show. We—my roadie, Maple, and the sound team—were moving with such clockwork that some nights it seemed as though we were rolling down the highway for the next town before the applause had stopped in the arena.

One month’s itinerary; design by Maple Byrne. Even though it indicates two shows at the Nassau Coliseum, a third was added. I remember nothing on this schedule except the Universal Amphitheatre—because it was in my hometown and opening the show were my friends the Blues Brothers—and the Nassau Coliseum, because of the harrowing helicopter ride to get from Manhattan to Long Island, with jets from LaGuardia Airport streaking all around us.

Sixty cities in sixty-three days. Seventy-two cities in eighty days. Eighty-five cities in ninety days. The Coliseum in Richfield, Ohio, largest audience in one day, 18,695. The Chicago International Amphitheatre: twenty-nine thousand people. Stealth limousines and subterranean entrances. I played Nassau Coliseum in New York. How many tickets sold? Forty-five thousand. I was astonished that popular culture had fixed its attention so intensely on my little act. This lightning strike was happening to me, Stephen Glenn Martin, who had started from zero, from a magic act, from juggling in my backyard, from Disneyland, from the Bird Cage, and I was now the biggest concert comedian in show business, ever. I was elated. My success had outstripped my wildest aspirations. I had hit a gusher, and I stopped checking prices in restaurants, hotels, and clothing stores. I bought my first house, and then I bought my second house, skillfully negotiated by my father. My wisecrack about success was “We’ll offer you fifty thousand dollars to go stand over there.” “I can’t,” I would say, “I’m getting seventy-five thousand to stand right here.” I had a line: “I think I’m spending my money wisely…. I just bought a three-hundred-dollar pair of socks. And last week I got a gasoline-powered turtleneck sweater.”