5 Internalizing Neoliberalism and Austerity

STEPHEN MCBRIDE AND SORIN MITREA

You are in charge of your career all the time, every day, in every situation. Workers can rely on “skills security” rather than long-term job security. Career self-management means not relying on any business, organization, government or union to look after your interests.

British Columbia Ministry of Advanced Training and Technology, June 1999

This message exemplifies the neoliberal approach to the labour market. Assuming the market is functioning properly, and that any rigidities posed by over-regulation have been removed, then success or failure within it is individually determined. Not long ago, the prevailing wisdom was that labour market problems experienced by individuals, such as unemployment, were largely systemic – the product of structural factors. One question this chapter asks is, How did we get to here from there? More specifically it focuses on whether and in what ways the individualist account of labour market success or failure has been internalized. To what extent have the state policies that have reconfigured the labour market, which will be briefly described in the first parts of the chapter, been accepted by those who have experienced them, often to their disadvantage when compared to labour market experiences in the previous period.

We engage in a comparative analysis of the United Kingdom and Canada as both countries have long narratives of austerity – dating back to the 1980s and 1990s – defined as fiscal consolidation and structural reforms that include labour market restructuring and flexibilization (Berry 2014; Blyth 2013). Labour market policies (LMP) operate at the intersection of social construction and coercion, making social support for the precarious contingent on undertaking training and attitudinal adjustment. Rather than simply responding to exogenous economic conditions (e.g., post-Fordist production and globalization), these policies are best understood as responsibilizing projects, materially and rhetorically devolving any social or collective responsibility for well-being to the subject. We use the literature to parse the ways in which people have reacted to the exigencies brought on by austere labour market policy.

Canada and the United Kingdom are excellent cases for a comparative analysis. Although the latter is a unitary and not federal system, both states are parliamentary, representative liberal democracies; both are residual liberal welfare states and industrially advanced liberal market economies; both are mid-sized powers internationally; and both have long histories of austerity and voluntarily undertook it after the global financial crisis (GFC) (Berry 2014; Blyth 2013; Macdonald 2014; Dunk 2002).

From Keynesianism to Neoliberalism: Full to Flexible Employment and the Individualization of Labour Market Performance

John Maynard Keynes considered most of the mass unemployment of the 1930s to be caused by a lack of effective aggregate demand – spending on consumption, investment, government, and net exports. If effective aggregate demand fell below the capacity of the economy to supply goods and services, then unemployment would occur. Contrary to the neoclassical orthodoxy of his day, Keynes argued that without effective demand the economy might remain in depression or recession. Government should therefore act to raise the level of aggregate demand, either through spending, intervening in the private economy to raise exports, or adjusting consumption or investment. The corollary of this approach was that, outside of exceptions, individual unemployed persons suffered from the shortfall in aggregate demand (a structural factor) rather than their own “failings.”

Keynes’s ideas were widely adopted after 1945. The “Golden Age” imaginary of post-war welfare capitalism, often depicted as an era of full employment managed by a benevolent state, came to define the Keynesian era. It came to an end, depending on place, somewhere between 1975 and 1995. Although this imaginary was somewhat inflated, it does provide a contrast with the increasingly austere neoliberal period that succeeded it.

Leaving aside the issue of how to explain this shift in policy paradigms, we can briefly summarize the neoliberal approach as involving the idea that state intervention in the economy obstructs the efficiency of the market and should therefore be reduced to a minimum. The primary means of constraining the state include privatization, deregulation, devolution, debt, and balanced budgets (austerity). The preferred method of achieving the last is through spending restraint rather than increased revenues via taxes, indicating that the overarching goal is not a balanced budget per se, but a reduced role for the state. Conversely, neoliberals tend to favour a strong but limited state, and so spending is maintained in areas like law and order, defence, and protection of property rights, while spending restraint typically befalls social programs, which redistribute through in-kind, free, or subsidized benefits such as education, health, pensions, and income security (Gamble 1998). With respect to the labour market, neoliberals argue that various problems, including unemployment, result from “rigidities” (typically measures that confer security to workers through negotiated settlements or regulation). Removal of these rigidities will overcome labour market problems by allowing the market to function efficiently (flexibly) with the onus on individuals to be flexible and adjust to changing circumstances.

This diffusion of market logics through the state has increased the diffusion of neoliberal “common sense” – a Gramscian concept that can be defined as a spontaneous, naturalized way of experiencing and living in the world (Knight 1998, 106; Hall and O’Shea 2013, 8). This common sense has several components: (1) the individual is the normative centre of society and should be as unencumbered by rules and collective responsibilities as possible; (2) the market is the most effective means through which individuals can maximize their own utility; (3) state actions that interfere with individual autonomy or market relations lead to an autocratic society; (4) these logics frame entrepreneurial practices and subjectivities as the rightful and necessary (for survival and success) culmination of individual responsibility, rational calculation (oriented towards self-interest), disciplined consumption, and “self-work” (Pierre 1995; Herd, Lightman, and Mitchell 2009). Consequently, dependence (“laziness”) is an immoral individual failing (Clarke and Newman 2012, 311).

Between the end of the Second World War and the mid-1970s, the Canadian labour market exhibited relatively full employment (compared to the preceding and subsequent periods) and security. Security refers to low unemployment levels, increased protection due to unionization, and low incidence of part-time or temporary work as compared to full-time, ongoing work. In the neoliberal period unemployment was generally higher and, equally important, the labour market was restructured towards less security for workers and more flexibility for employers (an umbilical linkage). In broad terms, therefore, we have moved from full employment to flexible employment. While flexibility can be advantageous for employees who have other time commitments, they rarely have control over scheduling (Lewchuk et al. 2013). Indeed, flexibility is typically in the interest of employers who determine the allocation and conditions of working time (Standing 1999).

Concurrently, consumption and survival continued to shift from wages – which stagnated – to debt, which prompted individual responses in overtime work and reduced consumption to meet rising debt obligations (Pathak 2014, 91). Indeed, the pre-GFC Anglo-American economies experienced a rapid rise in and proliferation of financialization via consumer credit, increasingly in unsecured (e.g., non-mortgage) liabilities (Montgomerie and Williams 2009, 100). As a result, individuals became further integrated into financial markets via more dangerous instruments (3). The state’s retreat from mitigating precarity (or regulating financial markets) permitted rising debt to take on a disciplinary character, necessitating consistent individual efforts to manage obligations so as to maintain consumption and survival (Pathak 2014, 93).

The degree to which workers enjoy security depends ultimately on their relative power vis-à-vis capital and the state, influenced by the mode of labour market regulation. Standing (1999) identifies three modes: regulation by the state, regulation by “voice” (through direct negotiations or bargaining between employers and workers), and regulation by the market. Although there are pros and cons to each regulatory mode, Standing argues that the post-war period (of full employment) was characterized by state regulation of the labour market that tended to extend labour’s rights and security. Regulation by the state or by voice are essentially collectivist forms of regulation. Regulation by a market stripped of its rigidities leads to labour market flexibility and the individualization of responsibility, described on the BC government website with which we opened the chapter.

Austerity: Policy and Morality

Austerity proponents claim that exorbitant public indebtedness is ruining the major economies and that neoliberal measures such as cutting spending (wages, prices, and general spending while cutting taxes) to eliminate deficits and debts would result in economic growth (Levinson 2013, 93; Blyth 2013, 2). Austerity policies also have “lock-in effects,” wherein cuts to public expenditures, revenue, and less economic stimulus leave governments with fewer options to address economic downturns (Levinson 2013, 91).

However, austerity is more than a policy orientation – it is a moral economy built around practices of consumption that frame individual responsibility for reduced consumption and resilience as practices of “good citizenship” (Knight 1998; Clarke 2005). Failing to make the virtuously necessary shared sacrifices compelled by crisis threatens the future of the subject and the community (Clarke and Newman 2012, 316). Moral austerity is tutelary insofar as it works to shape the behaviour of subjects through broad social relations or through the state (MacGregor 1999, 108).

Material precarity (financial/employment insecurity, debt, etc.) and the retrenchment of the social state contribute to psychological and physical trauma and cause the subject to “retreat inward,” increasingly abandoning social (let alone political) relations (Lewchuk et al. 2013; Slay and Penny 2013). Austerity intensifies precarity (through its effects of lower growth and subsequently lower-quality jobs, shrinking the state, and raising unemployment) and, through its own narrative of reduced consumption and individual responsibility, puts more pressure for individuals to be resilient, “lower their expectations,” and survive rather than strive to change austere trajectories. Assistance from the state is contingent on taking part in LMP training programs, and other support is dependent on social relations and existing assets, both of which are rapidly stretched in precarity (Berry 2014; Vrankulj 2012; Harrison 2013; Herd, Lightman, and Mitchell 2009). As labour protections retrench, wages stagnate, and precarity and unemployment rise, people must find a way to survive, and neoliberal austerity delineates the psychological and material mechanisms by which people may cope. Neoliberal LMP provides a “common sense” narrative of responsibilization: making the self employable, remaining flexible, and reducing consumption and expectations so as to be a resilient entrepreneurial subject (Read 2009; Pathak 2014).

Austerity unravels safety nets, with benefits and tax credits becoming less generous and more conditional and punitive, bifurcating the vulnerable between those who responsibilize (the “deserving poor”) and those who do not (Slay and Penny 2013, 11; Macdonald 2014). In the United Kingdom with budget 2014/15, this has taken the form of £19 billion per year in cuts to incapacity benefits (the hardest hit), tax credits, child benefits, housing benefits, disability living allowances, deductions, and introduction of benefit caps (Slay and Penny 2013, 11). In Canada, the 2014 federal budget enacted $14 billion in spending cuts or freezes to federal departments and operating budgets, continuing years of social service retrenchment, privatization, and devolution (putting more pressure on the provinces, such that Ontario’s 2014 budget forecast $2.1 billion in cuts and spending reductions) (Macdonald 2014; Tiessen 2014).

Relatedly, precarity has physiological, psychological, and social consequences, particularly for those with multiple disadvantages (e.g., unemployment, poverty, poor education, networks, and supports), which have been found to isolate individuals by compromising social networks, again driving them inward for survival (Benach et al. 2014). In a sample of 36,984 individuals aged fifteen and over in Canada, 28 per cent of those in the low-income population experienced high psychological distress, compared to 19 per cent in the non-low-income population (Caron and Liu 2011, 318). Similarly, in the United Kingdom, the least-skilled workers – disproportionately represented in precarious employment – are 21.6 per cent more likely to experience anxiety, are 288 per cent more likely to be depressed, are 121 per cent more likely to develop alcohol dependence, and have a 188 per cent higher mortality rate (all of these figures are exacerbated by unemployment and poverty) (Murali and Oyebode 2004, 218).

Social Construction and Responsibilization

Social construction describes the ways that policy design and implementation have material and psychological effects on subjectivity as a result of particular framings and discourses. Policies normatively construct subjects and their conditions by allocating resources and mobilizing narratives towards particular goals (Schneider and Ingram 1993, 93). Social construction in policy has “feedback” effects, wherein positive construction correlates strongly with political power resource (material and discursive) outcomes and more active political participation (98). In the case of austerity and neoliberal LMP, these policies operate as a moral project to conduct citizens’ behaviour and attitudes towards individual responsibility and employability as conditions for social support. As former UK prime minister Tony Blair said, “We accept our duty as a society to give each person a stake in its future. And in return each person accepts responsibility … to work to improve themselves” (Dam Sam Yu 2008, 386; Wainwright et al. 2010, 490). This is paralleled in Canada, as Stephen Harper recently noted: “We have to govern ourselves responsibly [and] the wealth we have today [has] to be earned in a very competitive … future” (Harper 2013). Subjects are increasingly expected to be independent, but hard working; autonomous, but responsible (e.g., avoiding binge drinking or over-eating); and to manage their lifestyles so as to promote their own health and well-being (Clarke 2005, 451).

The state utilizes supply-side1 LMP to construct responsibilized individuals: subjects who internalize a culture of self-discipline and are individually active in cultivating their success, health, and well-being, while making them responsible for it and to society (Knight 1998; MacGregor 1999). Responsibilization is based on the assumption that rises in inequality and poverty are a result of individual failings rather than structural design and morally equates self-care, discipline, responsibility, and self-containment (“you are responsible for yourself, but also for your effect on others”) with good citizenship and the realization of future security (MacGregor 1999, 108; Whitworth and Carter 2014, 110). In the case of supply-side LMP, individuals are called upon to answer to their moral responsibility for self-care (survival) and independence through discipline, sacrifice, and reduced consumption so as to secure their future (Herd, Lightman, and Mitchell 2009; Harrison 2013). Thus, while responsibility can operate in non-individualizing discursive regimes and has done so, it is framed through autonomy (individualization) and personal choice by neoliberalism and austerity as “common sense” (Knight 1998, 125; Whitworth and Carter 2014, 110).

In the context of labour, neoliberalism expands the logic of neoclassical economic theory to all social relations and behaviours, or, as Foucault said, “Homo economicus is an entrepreneur, an entrepreneur of himself” (Read 2009, 26). Supply-side LMP socially constructs “human capital,” not workers, through responsibilization: attempting to inculcate the idea of self-actualized (“activation”) “investment” in one’s skills or abilities so as to make oneself employable through market-based pedagogies (e.g., training, education, mobility, flexibility) (Pathak 2014, 105). Crucially, via supply-side LMP’s focus on individual will and dependency, entrepreneurial subjectivity is a moral enterprise whose outcomes in upward mobility, well-being, and independence are framed as utterly contingent on integration into the market, and failure as a result of a lack of individual will, responsibility, and moral conscience (105).

The Austere Worlds of Labour Market and Welfare Policy in the Neoliberal Era

In the 1970s, limitations emerged to Keynesian aggregate demand management in ensuring full-employment alongside global pressures to flexibilize labour markets and roll back the social state that protected and supported workers. As a result, labour market policy shifted from demand side to “active (e.g., training programs) supply side (focusing on individuals),” focusing on individuals’ employability, responsibility, and attitudes as responses to narratives of welfare dependence, rising fiscal deficits, and structural unemployment in the late 1980s and 1990s (Lightman, Herd, and Mitchell 2006; Nicholls and Morgan 2009). The OECD is an epistemic community that can be viewed as a principal architect promulgating flexible LMP by cultivating a consensus on these policies as “best practices” and providing a forum for the exchange and reinforcement of ideas. It became a strong sponsor of free market ideologies and, although it has no authority to enforce its recommendations or sanction non-compliance, it had considerable persuasive power (Kuruvilla and Verma 2006). The OECD Jobs Study reports, notwithstanding some internal differences, advocated a “one size fits all” set of policy recommendations for members’ labour, economic, and finance ministers to address rising unemployment through deregulation, market liberalization, activation of the unemployed, and removal of labour market rigidities (Noaksson and Jacobsson 2003, 31; Hodson and Maher 2002).

While compliance varied (e.g., among social market economies attempting to combine flexibility and security) and the OECD’s own benchmark indicators suggested their strategies do not produce predicted benefits, the liberal group of countries, which included our case studies in Britain and Canada, were the most compliant with OECD recommendations (McBride and Williams 2001).2 Liberal states provide minimal standards and focus on “activating” people to adapt to labour market conditions through means-tested assistance, modest social transfer to the working class and poor, stigmatized benefits, and heavy emphasis on employability rather than employment.

Consequently, equity objectives contended with efficiency motives in Canada3 (Little 2001) and the United Kingdom (Berry 2014), eventually leading to dilution of training, privatization of service delivery, and the individualization of labour market success. Responsibilization informs contemporary supply-side LMP in Canada and the United Kingdom, both of which tie welfare to LMP (“workfare”) and privilege rapid job placement (“work-first”), consequently forgoing substantial skill investment (Herd, Lightman, and Mitchell 2009; Harrison 2013). In the context of austerity, “activation” in LMP refers to “self-work,” wherein welfare recipients and the unemployed are required to take part in workfare programs that encourage individual solutions such as self-responsibility and attitudinal adjustment to lower expectations, reduced consumption, and be flexible (Clarke 2005; Read 2009).

Moral and fiscal austerity inform the devolution of labour market policy in Canada and the United Kingdom with the shift to work-first workfare models. In Canada in the mid-1990s, the federal government devolved more financial responsibility to the provinces for social support provision with the end of the Canada Assistance Plan (CAP) and the shift to the Canada Health and Social Transfer (CHST) in 1995 (Lazar 2006). The 1996 federal Employment Insurance Act similarly retrenched support and eligibility for employment insurance (EI) while devolving increasing responsibility for training to the provinces (who subsequently privatized many services) (Haddow and Klassen 2006). The provinces, then, typically devolved the implementation – and increasingly, financial burden – onto municipalities (who then often employed private contractors) (Herd, Lightman, and Mitchell 2009, 133).

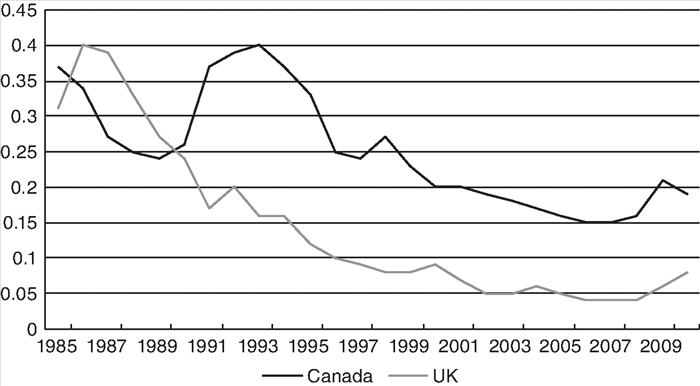

Similarly, in January 1998 the UK government launched the first of twelve “New Deals,” which devolved increasing implementation and management of workfare to local authorities and applied to anyone who was claiming an out-of-work benefit (Berry 2014; Nicholls and Morgan 2009). As with the Canadian shifts, the New Deals shifted financial benefits based on automatic entitlement of citizenship to users’ efforts to re-enter the labour market (Dam Sam Yu 2008; Smith 2013). In both Canada and the United Kingdom, the shift towards supply-side LMP devolves program responsibility to lower levels of government and responsibility for labour market outcomes to the individual, shifting eligibility based on an unconditional determination of need to market-based selectivity (Herd, Lightman, and Mitchell 2009; Slay and Penny 2013). Individualization and privatization in neoliberal LMP has been consistent with the fiscal consolidation of austerity, shifting emphasis to compulsion over voluntarism, sanctions over incentives, and individualized obligations over collective rights (Little 2001; Nicholls and Morgan 2009). The long-term effect on active labour market spending can be seen in figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1. Canadian and UK Funding for Active Labour Market Training Programs (% of GDP), 1985 to Present

Note: Most recent data for Canada were 2011 and 2010 for the United Kingdom. The OECD considers training programs, placements, and incentives (including unemployment support).

Source: OECD Statistics 2014.

Liberal market economies such as Canada and the United Kingdom pursued “work-first” (the New Deals in the United Kingdom and programs such as Ontario Works in Canada) workfare models,4which place priority on rapid labour force entry through compulsory participation,5 attitudinal adjustment, minimal retraining, and job search skills in short-term, low-cost programs (Herd, Lightman, and Mitchell 2009; Berry 2014). These measures – along with politicians, the media, and the public – push the idea that unemployment and poverty were individual failings in lacking skills, education, attitudes, morality, responsibility and flexibility6 (Dam Sam Yu 2008, 384; Herd, Lightman, and Mitchell 2009, 129). This approach individualizes blame and elides structural forces and policies that create unemployment and poverty, which results in individuals remaining in poverty and “cycling” between poor-paying jobs of low quality, with low retention and unemployment (Herd, Lightman, and Mitchell 2009, 134; Wainwright, Buckingham, and Marandet 2010, 495). Work-first programs privilege job search skills, “soft” skills (e.g., communication, problem-solving, assertiveness, and time management) and attitudinal adjustment (Herd, Lightman, and Mitchell 2009; Berry 2014). Compliance is obtained through a mixture of ideology (via attitudinal adjustment as social construction) and coercion, with the latter reinforcing the former.

For example, with the United Kingdom’s New Deal for Young People (NDYP), individuals were required to take part in either full-time education or vocational training for a year or subsidized employment in the private, voluntary, or public sector for six months (Berry 2014, 598). However, over 90 per cent of services were dedicated to job-search and related services such as job counselling, CV-writing, and search assistance (598; Nicholls and Morgan 2009, 83). The NDYP used soft social control (e.g., one-to-one advice) and hard sanctions such as the withdrawal of benefits for persistent “refusal to conform” by not completing programs, being late, or leaving early (Dam Sam Yu 2008, 385). Similarly, with Ontario Works (whose funding was cut by 17 per cent in 1996–7), the emphasis was disproportionately on job-seeking skills and attitudinal adjustment: in a 2009 study of four municipal programs in Ontario, all focused primarily on “life skills” such as résumé preparation, job coaching, interview preparation, and employers’ expectations; some focused specifically on work ethics, increased motivation, positively adjusting attitudes, and developing coping strategies; and failure to attend resulted in financial sanctions (Herd, Lightman, and Mitchell 2009, 139; Mendelsohn and Medow 2010). For those who cannot find work, “community participation” or unpaid work placements (which may not be covered by employment standards or EI) are required in exchange for welfare in the United Kingdom and Canada (Little 2001, 22; Nicholls and Morgan 2009, 83). Reduced consumption is enforced, as the state requires access to financial statements for up to a year, potentially forcing participants to sell assets (at the time, allowed liquidity was $520). Also, all income must be declared, including any help from others (Herd, Lightman, and Mitchell 2009).

These low-cost programs disseminate neoliberal ideology, encouraging workers to lower (“realistic”) expectations by adjusting individuals’ attitudes from “passivity and poor working habits” towards “activation” (Herd, Lightman, and Mitchell 2009, 136). Programs focus primarily on shaping participants’ attitudes, focusing daily on the financial and psychological value of work, independence, work ethic, and individual responsibility to develop “realistic expectations” about the labour market: as an Ontario facilitator said, “Take a lower-paying job at this time. Be realistic. It’s common sense” (146).7 Similarly, in the United Kingdom, programs were built around lowered expectations. As a policymaker said, “Our view [was] that retention depended on getting people job ready [more than] it did in the kind of support they had after they got a job” (Nicholls and Morgan 2009, 88). Negative situations, such as job loss, poverty, and even family death, could be “resolved” through attitudinal adjustment, according to Ontario facilitators: “You can be sad, depressed, angry … you have to find another road” (Herd, Lightman, and Mitchell 2009, 145).

Neoliberal Labour Market Policy Post-GFC

Around the time of the Global Financial Crisis and onward, workfare policies in the United Kingdom under the Coalition government pivoted towards correcting “individual failings” by addressing “the incentives and disincentives of benefits” (Slay and Penny 2013). However, the shift to “universal credit” as part of the 2012 Welfare Reform Act further retrenched social supports by cutting certain subsidies, introducing benefit caps and new sanctions (for not complying with workfare measures or not getting off welfare), and locking tax credits to only a 1 per cent increase a year instead of tying to inflation (Slay and Penny 2013, 1). As recently as May 2015, a Labour Party leadership contender in the United Kingdom expressed support for the Tories’ £12 billion cuts to social supports, including dropping benefit caps from £26,000 to £23,000 (Beattie 2015). In Canada after the GFC, the federal government extended EI benefits temporarily by five weeks, and five to twenty weeks of additional EI benefit were provided to the long-term unemployed, while active LMP spending rose only temporarily (see figure 5.1) (Bernard 2014, 34). Further, 2013 EI reforms forced claimants to take jobs with up to as much as a 30 per cent pay cut, and EI receipt has been falling 200 per cent faster than unemployment (Canadian Press 2013; Weir 2013). The results included a decline in coverage, such that while in 1987 some 87 per cent of the unemployed received benefits, only 36 per cent did in 2014 (PressProgress 2014). Similar results can be found in the United Kingdom,8 with approximately 86 per cent of the unemployed receiving benefits in 1987 compared to 50 per cent in 2014 (Office for National Statistics 2015). Again, the message of individual responsibility for labour market outcomes is reinforced by continued ideology and the depletion of benefits as a form of coercion.

Internalizing Neoliberalism and Austerity

In the remainder of this chapter, we provide an early-stage comparative content and statistical analysis to determine how people have reacted to precarity and LMP under neoliberalism and austerity in Canada and the United Kingdom. In looking at secondary sources, results will be organized under headings of attitudes towards the vulnerable, individual responsibility, market solutions, reduced expectations, moral judgments, and reduced consumption.

We are interested in how effective these policies have been in shaping individuals’ perspectives through the logics of neoliberalism and austerity. Faced with precarity and the individualizing and responsibilizing narrative offered by neoliberalism, austerity, and supply-side LMP, we propose that people will react on a spectrum of internalization (embracing responsibilization), disaffected consent (embodying responsibilization as primary survival recourse),9 and resistance (contesting responsibilization). On the basis of a review of secondary literature, we hypothesize that disaffected consent will be the most common response, speaking to the degree to which neoliberal austerity and LMP have undermined other forms and options of surviving and being, providing one main “path” (and narrative) for survival.

Attitudes towards the Vulnerable

Attitudes towards the unemployed and impoverished typically follow narratives of individual irresponsibility, laziness, dependency, and immorality that correlate with increased support for social service retrenchment (Krahn et al. 1987; Diprose 2015). These findings are validated in perceptions of poor and unemployed people in Canada (Fournier, Zimmermann, and Gauthier 2011) and in the United Kingdom (Taylor-Gooby and Taylor 2014):

• Benefits for the unemployed “discourage work” and self-sufficiency (2011): Canada 55.9 per cent agree; UK 62 per cent;

• “If people really want to work, they can find a job” (2011): Canada 70.9 per cent agree; UK 57 per cent;

• “People who don’t get ahead should blame themselves, not the system” (2011): Canada 56.8 per cent agree; UK 23 per cent10 (a 53.3 per cent increase since 1994).

The 2011 Canada Election Study found that 66.3 per cent of people believe that people should move if they can’t find work, a sentiment mirrored by participants in a UK study on perception of poverty: “Don’t go by what the Government says, but by what you see out there on the street, if people try to get a job they can get one” (Fournier, Zimmermann, and Gauthier 2011, 114; Castell and Thompson 2007, 18).

In several Canadian studies (Herd, Lightman, and Mitchell 2009; Little 2001; Collins 2005), the least privileged members of society (unskilled manual labour, poorly paid individuals, and even welfare recipients) appeared to internalize neoliberal perspectives, exhibiting the most negative and individualistic attitudes towards the unemployed. They cognitively and emotionally distance themselves from the “undeserving poor” who “have too many children, have never worked before, and who don’t try to better themselves” – results that are mirrored in the United Kingdom (Diprose 2015; Castell and Thompson 2007). These studies demonstrated a growing concern with “the future” of the polis, informing moral criticism of the “dependent” who would undermine the structure and sustainability of the community.

Individual Responsibility for Circumstances

Supply-side LMP as workfare frames culminate in narratives of “no legitimate dependency,” wherein almost “everything about people’s lives are deemed to be the responsibility of the individual” (Peacock, Bissell, and Owen 2014, 176). As a result, workfare socially constructs coping with precarity as an activity of individual resilience in practices and attitudes.

In a study in the United Kingdom, participants understood their own precarity as a result of individual failure (eliciting self-blame), and any attempt to use a non-individualistic lens was “seen as a way to shirk responsibilities and duties” (Peacock, Bissell, and Owen 2014, 176):

“It’s like making excuses, yeah? Because only I can do [change my circumstances], it’s all down to me … But it is about making the choices … so I am responsible aren’t I?” (UK participant; 176)

This is similar in the Canadian context:

“I’m not very happy with myself. I feel like I’m not doing anything worthwhile, I feel useless.” (Canadian participant; Fournier, Zimmermann, and Gauthier 2011, 322)

Without social support, unemployment and poverty put tremendous pressure on time, energy, and resources, which foreclose social, let alone political, relations in an effort to simply survive, while “no legitimate dependency” and the need for “responsibilization” disseminated by supply-side LMP may see people turn inward (Fournier, Zimmermann, and Gauthier 2011; Chase and Walker 2012; Little 2001, 17). Indeed, research has shown that experiences of poverty and unemployment rarely lead to heightened class consciousness (Dunk 2002, 233). In a Canadian study, unemployment (worse when poverty intersects) had negative effects on social relations and health, as 47 per cent felt depressed about their circumstances, 29 per cent reported that most of the days in the past month were stressful, and 47 per cent reported that family relations had become stressful (Vrankulj 2012, 22).

Accepting Market Solutions

Supply-side LMP engenders a sense of individual responsibility for precarity so as to socially construct subjects to be employable, mobile, flexible, and constantly “working on themselves” (“entrepreneurial subjectivity”) (Dunk 2002; Wainwright et al. 2010). At its core, supply-side LMP disseminates a narrative that what is fair, right, and reasonable is determined by the market:

“Life is what you make it if you can. Like nobody’s going to give you anything … Like they should give me a job … It doesn’t work that way.” (Canadian participant; Dunk 2002, 888)

“My career is rather unusual inasmuch as I’ve had probably three or four careers … I think it’s just the circumstances that you have presented to you in your life [and what you make of them].” (UK participant; Gabriel, Gray, and Goregaokar 2010, 1698)

Subjects in a Canadian study illustrated the intersection of austerity (via reduced consumption) and entrepreneurial subjectivity by “investing” in their “human capital” so as to render themselves employable: one respondent now saw “tuition fees as a form of investment and understood that he must forgo other spending to afford this,” and another saw negative events as “an opportunity to learn” (Buckland, Fikkert, and Gonske 2013, 345). Here subjects internalize the futurity of austerity in projecting the realization of sacrifice to the future (“investment”) and resilience in reframing vulnerability as opportunity.

There is an inherent futurity in retraining, letting go of expectations rooted in the past to prepare yourself for the new future, as was articulated in an Ontario retraining program: “Success is said to require ‘letting go of old patterns and behaviors’ and ‘looking forward to change as a challenge, taking risks and innovating’” (Dunk 2002, 887). Supply-side measures and “getting over” layoffs were accepted by some workers:

“[The retraining program] was good … they helped with the resumes and they [helped] people realize that the place was shut down … I think that was the whole point.” (Canadian participant; Dunk 2002, 888)

Reduced Expectations

One effect of the flexibilization of labour, precarity, and supply-side LMP is that expectations and aspirations for control over work (let alone for gratifying work) and the future are lowered so as to inure people to repeated deprivation and frustration (Dunk 2002). Indeed, reservation wages – the lowest that a worker will accept – decline over time as expectations degrade and needs increase (Nichols, Mitchell, and Lindner 2013, 4).

In a Canadian three-year longitudinal study, precarious employment and unemployment led workers to accept jobs for which they were overqualified and that offered little or no social protection (e.g., retirement plans, health insurance), paid a low and/or irregular wage, and were unfulfilling and precarious (Fournier, Zimmermann, and Gauthier 2011). There were similar findings in the United Kingdom (Slay and Penny 2013; Gabriel, Gray, and Goregaokar 2010) and other Canadian studies (Lewchuk et al. 2013; Vrankulj 2012). People’s feelings of precarity led to disaffected consent to labour market conditions:

“I’m feeling down, disappointed, lost. This is what work has become for me: I’m going to get a job I won’t hate too much for the next 15 years and that’s going to put money in my pocket, PERIOD … Before, I was passionate about work, it fulfilled my need to give and create.” (Canadian participant; Fournier, Zimmermann, and Gauthier, 2011, 322)

“Your dreams and your aspirations go out the window … I suppose for me it took a while for me to psychologically come to grips with the fact that I’m not longer going to be able to go out and [find] work.” (UK participant; Brown and Vickerstaff 2011, 539)

The restructuring of labour relations in Canada and the United Kingdom by capital and the state, which intensified during the 1980s, was also a form of social construction that inured subjects (particularly labour) to neoliberal capitalism (Dunk 2002, 884). Workers have been said to define their interests in relatively narrow and individualistic terms – what Lenin referred to as “trade union consciousness” – which by definition accepts the capitalist paradigm, even if conflicts over wages, benefits, and working conditions occur (885). Younger and more educated workers expressed more neoliberal interpretations and anti-union sentiments:

“[The union] were totally ridiculous in their expectations, totally unreasonable … There’s no reason in the world why guys with grade eight training should have been uh getting uh you know 20 bucks an hour, 22, 25 dollars an hour.” (Canadian participant; Dunk 2002, 893)

Moral Judgments

As mentioned previously, the least privileged members of several studies exhibited the most individualistic attitudes towards the unemployed, cognitively and emotionally distancing themselves from the “undeserving poor” so as to “attribute their relative success to personal factors that explain the failure of the unemployed” (Krahn et al. 1987, 229). Indeed, the surveillance and micromanagement (via sanctions, attendance, activity reports, and completion of program hours) of workfare LMP socially construct the poor as morally suspect – a view that they may internalize (Little 2001; Berry 2014). In this way, subjects internalize the dichotomies promulgated by workfare policies and their underlying ideologies.

However, the precarious are also likely to blame themselves, as several studies in the United Kingdom (Chase and Walker 2012; Smith 2013; Gabriel, Gray, and Goregaokar 2010) and Canada (Fournier, Zimmermann, and Gauthier 2011; Collins 2005; Little 2001) indicate that the poor and unemployed score statistically higher on anxiety, blame, shame, and guilt (also articulated through feeling “awkward, embarrassed, useless, worthless, a failure”). Self-blame of and in combination with precarious conditions often leads to a downward spiral of negative mental and health outcomes, reduced expectations, social isolation, and retreating inward:

“Many of the single mothers I interviewed were … desperate to prove that they are deserving and faithfully feeding their children.” (Canadian study; Little 2001, 19)

Impoverished participants in a 2005 Canada study categorized the precarious as “withdrawn and afraid” while expressing a sense of guilt “for every little thing you do,” while others spoke of “daily humiliations from government agencies” (Collins 2005, 21). These subjects felt as if they lived “under a giant microscope” (a kind of panopticism) which added to the “stress, guilt, shame, and self-blame about living on inadequate income” (18).

Reduced Consumption

Studies in the United Kingdom (Chase and Walker 2012; Harrison 2013) and Canada (Vrankulj 2012; Buckland, Fikkert, and Gonske 2013; Collins 2005) illustrate that, once unemployed, people typically react first by reducing consumption. Further, the long-term unemployed displayed 16–24 per cent lower consumption than the unemployed (Nichols, Mitchell, and Lindner 2013, 3). Common survival strategies include reducing consumption of non-essentials and then essentials, spending savings/retirement funds, selling assets, borrowing from friends, going into debt, and putting off needed health care. In a Canadian longitudinal analysis of laid-off workers, 48 per cent reported reducing consumption (“done without something you needed”) to make ends meet, with 40 per cent having difficulty with debts (Vrankulj 2012, 22). Similarly, in a UK study, participants did more than reduce consumption in having to choose between bills, food, or shelter for their children (Chase and Walker 2012, 742; Harrison 2013, 105). There are limits to the resourcefulness of reduced consumption, such that with very limited social assistance or funds, stress and sacrifice intensifies towards the end of each month (Collins 2005, 18).

“When my bills come in I have to sit down and rummage through my cupboards just to see what I can stretch for a week … when [utilities] bills come in that’s the worst, I cannot afford it. Simple. I have to turn off the heating and get out of the house because it is too cold.” (UK participants; Slay and Penny 2013, 4)

Although reduced consumption is frequently framed as a mechanism to secure the future, for many it elicits another kind of disaffection, limiting their abilities to imagine survival, let alone something more (Clarke and Newman 2012):

“There is no money coming in. I keep worrying: ‘What’s going to happen to me? Where will I end up?’” (Canadian participant; Fournier, Zimmermann, and Gauthier 2011, 321)

Conclusion

The structural shifts in Canadian and UK (and beyond) labour conditions and LMP require a modicum of acceptance by citizens to be sustained. The ever-increasing precarity wrought by austerity and the neoliberal labour market put subjects in a position where they have to find a way to survive. The ephemeral stimulus post-GFC was merely a blip in a continued trajectory of austerity. The state utilizes supply-side LMP to devolve responsibility for precarity to the individual, legitimated by a powerfully resonant narrative of coping via a moral responsibility to be flexible, to work on the self, and to discipline consumption (Hall and O’Shea 2013). Our analysis has illustrated how workers, the unemployed, and the impoverished live by neoliberal and austere ideas even if they do not embrace them: in a paradigm that strips social support and opportunity, all that is left is individual resilience. Perhaps the ultimate success of the neoliberal and austere state is in defining the conditions of life, regardless of the conditions of thought.

References

Beattie, Jason. 2015. “Andy Burnham Vows to Get Tough on Benefits If He Wins Labour Leadership Race.” Mirror (Stafford, TX), 29May. http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/andy-burnham-vows-tough-benefits-5786479.

Benach, J., A. Vives, M. Amable, C. Vanroelen, G. Tarafa, and C. Muntaner. 2014. “Precarious Employment: Understanding an Emerging Social Determinant of Health.” Annual Review of Public Health 35 (1): 229–53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182500.

Bernard, Prosper M.,Jr. 2014. “Canadian Political Economy and the Great Recession of 2008–09: The Politics of Coping with Economic Crisis.” American Review of Canadian Studies 44 (1): 28–48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02722011.2014.885542.

Berry, Craig. 2014. “Quantity over Quality: A Political Economy of ‘Active Labour Market Policy’ in the UK.” Policy Studies 35 (6): 592–610. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2014.971730.

Blyth, Mark. 2013. Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brown, Patrick, and Sarah Vickerstaff. 2011. “Health Subjectivities and Labour Market Participation: Pessimism and Older Workers’ Attitudes and Narratives around Retirement in the United Kingdom.” Research on Aging 33 (5): 529–50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0164027511410249.

Buckland, Jerry, Antonia Fikkert, and Joel Gonske. 2013. “Struggling to Make Ends Meet: Using Financial Diaries to Examine Financial Literacy among Low-Income Canadians.” Journal of Poverty 17 (3): 331–55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2013.804480.

Canadian Press. 2013. “Employment Insurance Canada Changes in Effect as of January 6, 2013.” HuffPost Politics, 6 January. http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2013/01/06/employment-insurance-canada-changes-2013_n_2421333.html.

Caron, Jean, and Aihua Liu. 2011. “Factors Associated with Psychological Distress in the Canadian Population: A Comparison of Low-Income and Non Low-Income Sub-Groups.” Community Mental Health Journal 47 (3): 318–30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10597-010-9306-4.

Castell, Sarah, and Julian Thompson. 2007. Understanding Attitudes to Poverty in the UK: Getting the Public’s Attention. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Chase, Elaine, and Robert Walker. 2012. “The Co-construction of Shame in the Context of Poverty: Beyond a Threat to the Social Bond.” Sociology 47 (4): 739–54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0038038512453796.

Clarke, John. 2005. “New Labour’s Citizens: Activated, Empowered, Responsibilized, Abandoned?” Critical Social Policy 25 (4): 447–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0261018305057024.

Clarke, John, and Janet Newman. 2012. “The Alchemy of Austerity.” Critical Social Policy 32 (3): 299–319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0261018312444405.

Collins, Stephanie Baker. 2005. “An Understanding of Poverty from Those Who Are Poor.” Action Research 3 (1): 9–31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1476750305047983.

Dam Sam Yu, Wai. 2008. “The Normative Ideas That Underpin Welfare-to-Work Measures for Young People in Hong Kong and the UK.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 28 (9/10): 380–93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01443330810900211.

Diprose, Kristina. 2015. “Resilience Is Futile: The Cultivation of Resilience Is Not an Answer to Austerity and Poverty.” Soundings: A Journal of Politics and Culture 58:44–56. http://dx.doi.org/10.3898/136266215814379736.

Dunk, Thomas. 2002. “Remaking the Working Class: Experience, Class Consciousness, and the Industrial Adjustment Process.” American Ethnologist 29 (4): 878–900. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/ae.2002.29.4.878.

Fournier, Genevieve, Helene Zimmermann, and Christine Gauthier. 2011. “Instable Career Paths among Workers 45 and Older: Insight Gained from Long-term Career Trajectories.” Journal of Aging Studies 25 (3): 316–27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2010.11.003.

Gabriel, Yiannis, David E. Gray, and Harshita Goregaokar. 2010. “Temporary Derailment or the End of the Line? Managers Coping with Unemployment at 50.” Organization Studies 31 (12): 1687–712. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0170840610387237.

Gamble, Andrew. 1998. The Free Economy and the Strong State.London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hall, Stuart, and Alan O’Shea. 2013. “Common-Sense Neoliberalism.” Soundings: A Journal of Politics and Culture 55:8–24.

Haddow, Rodney, and Thomas Klassen. 2006. Partisanship, Globalization, and Canadian Labour Market Policy: Four Provinces in Comparative Perspective. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Harper, Stephen, interview by Robert E. Ruben. 2013. “A Conversation with Stephen Harper,” 16 May. Council on Foreign Relations. http://cfr.org/canada/conversation-stephen-harper-prime-minister-canada/p35473.

Harrison, Elizabeth. 2013. “Bouncing Back? Recession, Resilience and Everyday Lives.” Critical Social Policy 33 (1): 97–113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0261018312439365.

Herd, Dean, Ernie Lightman, and Andrew Mitchell. 2009. “Searching for Local Solutions: Making Welfare Policy on the Ground in Ontario.” Journal of Progressive Human Services 20 (2): 129–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10428230902871199.

Hodson, Dermot, and Imelda Maher. 2002. “Economic and Monetary Union: Balancing Credibility and Legitimacy in an Asymmetric Policy-Mix.” Journal of European Public Policy 9 (3): 391–407.

Knight, Graham. 1998. “Hegemony, the Media, and New Right Politics: Ontario in the Late 1990s.” Critical Sociology 24 (1–2): 105–29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/089692059802400106.

Krahn, H., G.S. Lowe, T.F. Hartnagel, and J. Tanner. 1987. “Explanations of Unemployment in Canada.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 28 (3–4): 228–36.

Kuruvilla, Sarosh C., and Anil Verma. 2006. “International Labour Standards, Soft Regulation, and National Government Roles.” Journal of Industrial Relations 48 (1): 41–58.

Lazar, Harvey. 2006. “The Intergovernmental Dimensions of the Social Union: A Sectoral Analysis.” Canadian Public Administration 49 (1): 23–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-7121.2006.tb02016.x.

Levinson, Mark. 2013. “Austerity Agonistes.” Dissent 60 (3): 91–5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/dss.2013.0071.

Lewchuk, Wayne, Michelynn Lafleche, Diane Dyson, Luin Goldring, Alan Mesisner, Stephanie Procyk, Dan Rosen, John Shields, Peter Viducis, and Sam Vrankulj. 2013. “It’s More Than Poverty: Employment Precarity and Household Well-being.” Poverty and Employment Precarity in Southern Ontario (PEPSO). https://pepso.ca/case-studies/case-study-1/.

Lightman, Ernie, Dean Herd, and Andrew Mitchell. 2006. “Exploring the Local Implementation of Ontario Works.” Studies in Political Economy 78 (1): 119–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19187033.2006.11675104.

Little, Margaret. 2001. “A Litmus Test for Democracy: The Impact of Ontario Welfare Changes on Single Mothers.” Studies in Political Economy 66 (1): 9–36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19187033.2001.11675209.

Macdonald, David. 2014. “Budget 2014: Let Stagnation Reign.” Behind the Numbers: A Blog from the CCPA, 11 February. http://behindthenumbers.ca/2014/02/11/budget-2014-let-stagnation-reign/.

MacGregor, Susanne. 1999. “Welfare, Neo-Liberalism and New Paternalism: Three Ways for Social Policy in Late Capitalist Societies.” Capital and Class 23 (1): 91–118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/030981689906700104.

Mahon, Rianne. 2011. “The Jobs Strategy: From Neo- to Inclusive Liberalism?” Review of International Political Economy 18 (5): 570–91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2011.603668.

Mendelsohn, Matthew, and Jon Medow. 2010. Help Wanted: How Well Did the EI Program Respond during Recent Recessions?Toronto: Mowat Centre for Policy Innovation.

Montgomerie, Johnna, and Karel Williams. 2009. “Financialised Capitalism: After the Crisis and beyond Neoliberalism.” Competition & Change 13 (2): 99–107.

Murali, Vijaya, and Femi Oyebode. 2004. “Poverty, Social Inequality and Mental Health.” Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 10 (3): 216–24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/apt.10.3.216.

Nicholls, Rachel, and W. John Morgan. 2009. “Integrating Employment and Skills Policy: Lessons from the United Kingdom’s New Deal for Young People.” Education, Knowledge & Economy 3 (2): 81–96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17496890903132453.

Nichols, Austin, Josh Mitchell, and Stephan Lindner. 2013. Consequences of Long-Term Unemployment. Washington, DC:Urban Institute.

Noaksson, Niklas, and Kerstin Jacobsson. 2003. The Production of Ideas and Expert Knowledge in OECD: The OECD Jobs Strategy in Contrast with the EU Employment Strategy. Stockholm: Stockholm Centre for Organizational Research.

OECD Statistics. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2014. http://stats.oecd.org/.

Office for National Statistics. 2015. “Key Economic Time Series Data,” 17 April. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/site-information/using-the-website/time-series/index.html#3.

Pathak, Pathik. 2014. “Ethopolitics and the Financial Citizen.” Sociological Review 62 (1): 90–116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12119.

Peacock, Marian, Paul Bissell, and Jenny Owen. 2014. “Dependency Denied: Health Inequalities in the Neo-Liberal Era.” Social Science & Medicine 118:173–80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.006.

Pierre, Jon. 1995. “The Marketization of the State: Citizens, Consumers, and the Emergence of the Public Market.” In Governance in a Changing Environment, ed. Guy Peters and Donald Savoie, 55–81. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

PressProgress. 2014. “Unemployed? Good Luck Getting EI as Eligibility Hits All-Time Low,” 2 August. http://www.pressprogress.ca/en/post/unemployed-good-luck-getting-ei-eligibility-hits-all-time-low-0.

Read, Jason. 2009. “A Genealogy of Homo-Economicus: Neoliberalism and the Production of Subjectivity.” Foucault Studies 6:25–36. http://dx.doi.org/10.22439/fs.v0i0.2465.

Schneider, Anne, and Helen Ingram. 1993. “Social Construction of Target Populations: Implications for Politics and Policy.” American Political Science Review 87 (2): 334–47. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2939044.

Slay, Julia, and Joe Penny. 2013. Surviving Austerity: Local Voices and Local Action in England’s Poorest Neighbourhoods. London: New Economics Foundation.

Smith, Fiona. 2013. “Parents and Policy under New Labour: A Case Study of the United Kingdom’s New Deal for Lone Parents.” Children’s Geographies 11 (2): 160–72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2013.779443.

Standing, Guy. 1999. Global Labour Flexibility. London: Macmillan.http://www.palgrave.com/us/book/9780333773147.

Taylor-Gooby, Peter, and Eleanor Taylor. 2014. British Social Attitudes 32: Benefits and Welfare. London: NatCen Social Research.

Tiessen, Kaylie. 2014. “Austerity 2.0: Kinder and Gentler, but a Cut Is Still a Cut.” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, 1 October. http://behindthenumbers.ca/2014/10/01/austerity-2-0-kinder-and-gentler-but-a-cut-is-still-a-cut/.

Vrankulj, Sam. 2012. Finding Their Way: Second Round Report of the CAW Worker Adjustment Tracking Project. Toronto: Canadian Auto Workers.

Wainwright, Emma, Susan Buckingham, Elodie Marandet, and Fiona Smith. 2010. “‘Body Training’: Investigating the Embodied Training Choices of/for Mothers in West London.” Geoforum 41 (3): 489–97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.12.006.

Weir, Erin. 2013. “EI Benefits Falling Faster Than Unemployment.” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, 18 July. http://behindthenumbers.ca/2013/07/18/ei-benefits-falling-faster-than-unemployment/.

Whitworth, Adam, and Elle Carter. 2014. “Welfare-to-Work Reform, Power and Inequality: From Governance to Governmentalities.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies 22 (2): 104–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2014.907132.

Footnotes

1 Supply-side measures focus on individual employability rather than job creation (“demand side”) (Lightman, Herd, and Mitchell 2006).

2 See Mahon (2011) for an alternative view.

3 See McBride (1992, chap. 5).

4 Welfare support for post-secondary education was abolished in 1996 in Ontario, and support for full-time education or vocational training drifted with the United Kingdom’s “New Deals” in 1998 (Little 2001, 21; Berry 2014, 598).

5 Failure to attend, not completing sufficient hours, leaving early, or refusing employment results in the withdrawal of benefits in both the United Kingdom and Canada (Herd, Lightman, and Mitchell 2009, 136; Smith 2013, 162).

6 While welfare receipt would “engender laziness,” resulting in long-term reliance on public assistance and a drag on social services, the state, and society (moral austerity) (Little 2001; Diprose 2014).

7 Throughout the experience in Ontario, researchers did not observe participants ask any questions or resist: “The practice made sense to all involved,” exhibiting internalization (Herd, Lightman, and Mitchell 2009, 142).

8 This is a general comparison of trends and does not account for the differences between Canadian Employment Insurance and the UK Job Seeker’s Allowance.

9 A conditional and grudging, rather than enthusiastic, consent (Clarke and Newman 2012, 316).

10 It is beyond the scope of this chapter to address the difference between Canada and the United Kingdom in this measure, but the 1993 Canada Election Study showed 50.5 per cent support for the statement, so it appears both countries are becoming more comfortable with individualist attributions for precarity.