WAGGONERS’ WALK. After the demise of Mrs. Dale’s Diary/ The Dales, Radio 2 sought to introduce a more socially relevant daily serial that would reflect modern life. The result was Waggoners’Walk, which was broadcast Monday–Friday from 1969–1980 (2,824 episodes). Piers Plowright was one of its first producers.

WALKER, JOHNNIE (1945– ). Johnnie Walker has been one of the major figures in the development of music radio in the UK since his time on the pirate radio station Radio Caroline. When the Marine Offences Bill took effect on 14 August 1967, Walker, and his fellow Caroline disc jockey, Robbie Dale, defied the legislation and continued broadcasting past the midnight deadline, when all other offshore stations had fallen silent. It was reputed that, on this occasion, the audience was more than 20 million listeners Europe-wide.

From 1969–1976, Walker worked for Radio 1, where he gained a reputation for his knowledge of and respect for the music he played on his programs, pioneering then new names, such as Steve Harley, Lou Reed, Fleetwood Mac, and Steely Dan. Often outspoken and controversial, Walker left Radio 1 in 1976 after a disagreement with the station controller, Johnny Beerling, and moved to San Francisco, where he recorded a weekly program broadcast on Radio Luxembourg.

In the first years of the 1980s, he returned to the UK, and after periods on local radio in the west of England, he worked on Radio 5 before joining Radio 2 to take over the early evening drive-time program upon the retirement of John Dunn in 1998. He moved to a Sunday evening slot in 2006.

WALTERS, JOHN (1939–2001). This award-winning British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) producer and broadcaster began as an artist and teacher, later becoming a musician, working with the Alan Price Set, and even playing on the same bill as the Beatles in their last ever British stage appearance. He joined Radio 1 at its creation in 1967. Two years later, he began his long association with John Peel, a partnership that lasted more than 20 years. His wry and witty sense of humor and turn of phrase made him a popular broadcaster in his own right. For a time, he hosted his own programs, Walters Weekly (which became Walters Week) on Radio 1, and Largely Walters on Radio 4, in addition to creating a series of comic monologues featured in programs by other broadcasters. He left the BBC staff in 1991.

WARTIME BROADCASTING. The role of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) during World War II is important and must be considered from two perspectives: home front and overseas broadcasting. By the time of commencement of hostilities, the Corporation had had time to establish its policy clearly, including, where appropriate, evacuating and/or resiting of certain services. Within days of the announcement, a “Supplementary Edition” of Radio Times was published, carrying the banner, “Broadcasting Carries On.”

Because a depleted workforce on the domestic scene was augmented by many who found themselves in an unfamiliar situation, morale was a crucial issue, and the BBC created a number of new programs to cater to this requirement, such as Workers’ Playtime and Music while You Work. Other programs supported the government’s “Dig for Victory” campaign, including The Kitchen Front, Back to the Land, and The Radio Allotment. In the early days, J. B. Priestley’s Postscript program, broadcast after the Sunday evening news, countered the lowering of morale caused by the broadcasts of William Joyce, and in the last year of the war, Allied progress across Europe was monitored by the nightly War Report program.

The Variety Department created a range of light entertainment programs, many of which were to move into radio legend, such as Band Waggon and It’s That Man Again (ITMA). A new, relaxed style began to emerge in programming, partly caused as the war continued by the influx of U.S. and Canadian broadcasters, who, together with the BBC, created a tripartite Forces broadcasting service that gave UK domestic audiences—who could also listen—a taste for a new style of radio.

At the same time there were some who felt that BBC programs were becoming more vulgar and were catering to a lower common denominator than previously. The Forces Programme was requested to use material that was aimed at raising of standards and providing more informative content; this led to the creation of The Brain’s Trust, which, with a weekly postbag of up to 4,000 letters, became the first “serious” program to attract a mass audience.

As with domestic programming, the BBC’s overseas output had been primed for the event of war for several years. Countering German propaganda broadcasts became an increasing concern of the British government from 1933, when the Nazis came to power, and the BBC was asked to respond; this it did in 1938 with the creation of the Arabic Service as well as services in Spanish and Portuguese. Between 1940–1941, the BBC increased its overseas output threefold. Crucially, a special service to North America was created that demonstrated to the United States the true situation in a beleaguered Great Britain, with dramatized documentary programs, such as The Stones Cry Out.

At this time, services also began in every major European language. In 1941, as the expanding provision dictated the need for more space, the BBC took over the Bush House studios, formerly used by the J. Walter Thompson Organization’s commercial radio division. This became the headquarters of the European Service, and went on to be— for many overseas listeners even after the war—the true home of BBC radio. It was from Bush House, on the BBC’s French Service, that Charles de Gaulle made his first broadcast—on 18 June 1940—four days after the fall of Paris. From this, the French Resistance was created with a force estimated to be 56,000 strong.

It is hard to overestimate the importance of the role of the BBC during World War II. The Corporation had entered the war somewhat demoralized, with areas of its output under siege from commercial interests, such as the International Broadcasting Company (IBC) and Radio Luxembourg. By 1945, the BBC was an organization commanding global respect. This may be measured by the fact that in September 1939 it was transmitting in seven languages. By 1945, there were more than 40 services, and the staff of the BBC had more than doubled.

WAR REPORT. War Report was first broadcast by British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) radio after the nine o’clock news on D-Day, 6 June 1944, and continued nightly until 5 May 1945. From the initial landings until the final defeat of Nazi Germany, it gave millions of listeners a nightly picture of the progress of the war through the eyes of the men on the spot.

Using the new recording technology of the Midget disc recorder, relatively lightweight and portable, BBC correspondents such as Richard Dimbleby, Frank Gillard, Wynford Vaughan-Thomas, and Godfrey Talbot relayed vivid word pictures to the waiting audience in Great Britain. Reports usually reached the listener within 24 hours of having been recorded. Among the most famous reports was Richard Dimbleby’s moving account of the liberation of the Belsen concentration camp. Fundamentally, the necessities created by the policy decision to cover the last stages of the war in this way changed radio as a news-gathering medium forever.

WARNER, JACK (1895–1981). Jack Warner (real name Horace John Waters) was the brother of Elsie and Doris Waters. Having initially trained as an engineer, just prior to the outbreak of World War I, he worked as a mechanic in Paris and gained a good working knowledge of French. From 1914–1918, he worked as a driver with the Royal Flying Corps, based in France, after which he returned to his work as a mechanic, this time in England. His war years had seen his beginnings as an entertainer in concert parties, but he was over 30 before he became a professional entertainer.

In 1935, he made his West End debut, at which point he changed his name to Warner. It was, however, with his role in the radio show, Garrison Theatre in 1939, that his fame was assured. After the war, he played Joe Huggett in the successful radio comedy show, Meet the Huggetts. Thereafter, an increasingly successful career in television and film beckoned, and as PC George Dixon in the popular TV series, Dixon of Dock Green, which ran from 1955–1976, he reached a major new audience.

With no formal training, Warner’s great gift was sincerity, a quality heard and understood by the radio microphone, which established him as a major British star with an affectionate following.

WATERS, ELSIE AND DORIS. Elsie (1893–1990) and Doris (1899–1978) were together one of the most famous and popular comedy double acts in British variety, and, as their on-stage personas, “Gert and Daisy,” two cockney women, appeared in every medium. Two sisters, they never married and lived together all their lives. Their first radio broadcast was in 1929, and this led to a record contract. For one of their commercial recordings, they created the characters for which they were ever known; this was played on air by Christopher Stone, and a highly successful career resulted. It was said that the East London working-class sound of the act appealed to an audience alienated by the Reithian British Broadcasting Corporation’s (BBC) policy of standard English presentation.

In March 1934, the Waters sisters appeared on Henry Hall’s Guest Night, and two months later they appeared in their first Royal Variety Performance. The act was a particular favorite of Queen Elizabeth, later the Queen Mother. During World War II, they regularly appeared on such programs as Workers’ Playtime. After the war, they both received OBEs. “Gert and Daisy” continued to perform until the 1970s.

WATTS, CECIL (1896–1967). Watts was a musician who had worked in the early days of 2LO as a musician. His major contribution, however, was the invention of direct disc recording, a technology he devised in order to replay rehearsals to his band, but which was adopted as a revolutionary instant recording device by program makers. In order to manufacture the number of discs required, which he and his wife Agnes called the Marguerite Sound System [later Studios] (MSS) based on a name that occurred on both sides of their family, he established a factory, initially in London’s Shaftesbury Avenue, then in Charing Cross Road, and subsequently at Kew.

The demand came first from commercial radio, although the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) began to buy the Watts discs in quantity in April 1934. The importance of the invention was that for the first time broadcasters had access to an instant, cheap, and durable playback system, and the development of the recording of program material was immeasurably enhanced. Watts later developed a means of cleaning discs during playback, a device he called the “Dust Bug.”

WEAK ENDING. The longest-running British radio comedy program ever, which went out from Radio 4 on Friday evenings from 1970, produced by Simon Brett and David Hatch. It was originally written by Pete Spence. Since then, the program has had 27 producers and more than 65 writers, among them Jimmy Mulville, Griff Rhys Jones, and Douglas Adams. Growing out of the tradition of Oxbridge satire, the show frequently found itself on dangerous ground, as in 1980, when the journalist and broadcaster Derek Jameson attempted—and failed—to sue over a biting sketch that attacked him for his alleged lack of intellect.

WESTERN BROTHERS. Kenneth (?–1963) and George (?–1969) Western, were a double act that satirized the British upper classes. Known as “The Wireless Cads,” they were actually cousins and had solo careers until they first met in 1925, when they formed one of the most successful acts on stage and radio. They broadcast from the 1930s onward, including during and after World War II, although the peak of their fame and success was undoubtedly during the 1930s, when they were featured in cabaret, variety, and radio. Frequently, their monologues and routines used the paternalistic BBC as a target, with such items as “O Dear, What Can the Matter Be, No One to Read Out the News,” “The Old School Tie,” and “We’re Frightfully BBC.” The style was that of a languid, unison drawl, and on stage, they wore evening dress and monocles.

WHALE, JAMES (1951– ). This controversial and aggressive talk-show host developed a style similar to some of the U.S.-based “shock-jocks,” engaging in belligerent debate with phone-in callers, and frequently verbally attacking their views on air. First heard on Metro Radio in the 1970s, he moved to Radio Aire in 1981, where his program was also televised by Yorkshire TV. After leaving radio to concentrate on television, he returned to work on the national talk station, TalkSport, where in 2005, he was broadcasting a late-night phone in.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW? This quiz show created by John P. Wynn for the Light Programme was chaired by Franklin Engelmann and contestants competed for the title “Brain of Britain.” The program was first broadcast in 1953 and transferred to television in 1958 under the title Ask Me Another. In 1967, the radio version was renamed Brain of Britain.

WHILEY, JO (1965– ). Jo Whiley joined Radio 1 in 1993 and became known for her extensive and in-depth knowledge of popular music; her programs frequently feature interviews and live sessions with major contemporary musicians. She has been associated with the Glastonbury Festival, and copresented for Radio 1 from the Festival with John Peel. In 1998, she received the Sony Radio Academy Award for disc jockey of the year. See also WOMEN.

WHITBY, TONY (1929–1975). Tony Whitby was controller of Radio 4, in the early 1970s, and was involved with the development of many highly significant programs during his time on the network, including Kaleidoscope and I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue.

WHITE, PETER (1947– ). Peter White, blind since birth, has been the main presenter for the Radio 4 program for the visually impaired, In Touch, which he joined in 1974. He began his radio career in 1971 with Radio Solent in Southampton. Since 1995, he has been the BBC’s disability affairs correspondent. Between 1995 and 2005, he wrote four series of autobiographical talks for Radio 4. He also presented many programs for television, and in 1999, he published his autobiography, See It My Way.

WHITLEY, JOHN HENRY (1866–1935). Whitley became chairman of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) in 1930, succeeding George Clarendon. Coming from a family cotton business, Whitley became an MP and subsequently Speaker of the House of Commons. Following the dispute between John Reith and Clarendon a document was drawn up that laid out the rights and duties of the chairman and the members of the Board of Governors. This became known as the Whitley Document and established a status quo whereby the BBC presented a unified face to the outside world. Reith and Whitley maintained a good relationship and Whitley died in office. See also OLIVER WHITLEY.

WHITLEY, OLIVER (1912–2005). Oliver Whitley, the son of J. H. Whitley joined the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) in 1935, and in 1939, was attached to the Monitoring Service, which was at that time expanding into a 24-hour operation monitoring 150 foreign news bulletins every day. Whitley resigned in 1941 and spent wartime service in the navy. He rejoined the BBC after the war in 1946, and was immediately seconded to the Colonial Office to advise on the development of broadcasting in British overseas territories. He returned in 1949 as head of the General Overseas Service; in 1955 he was appointed assistant controller, Overseas Service.

In 1958, Whitley left Bush House and took up the post of appointments officer and then controller of staff training and appointments. He became chief assistant to Hugh Greene during the latter’s tenure as director-general of the BBC and served on the Board of Management. He ended his career in the Corporation as the first managing director of the External Services, a post he held from 1969 until his retirement in 1972.

WHITNEY, JOHN (1930– ). John Whitney became involved in radio in 1951 when he founded Ross Radio Productions, producing programs for Radio Luxembourg. A particular success from this time was People Are Funny. Always a passionate advocate of commercial radio, he cofounded the Local Radio Association, an organization created to encourage the introduction of self-funding radio in the UK, in 1964. He was founding managing director of Capital Radio from 1973–1982, at which time he was appointed director-general of the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA), a post he held until 1989.

Whitney was chairman of the Association of Independent Radio Contractors (AIRC) from 1973–1975 and again in 1980. Among his numerous executive posts, he has been chairman of the Sony Radio Academy Awards and chairman of Radio Joint Audience Research (RAJAR).

WILLIAMS, KENNETH (1926–1988). This highly talented actor is remembered for his camp portrayal of an array of bizarre comedy characters—in particular in Beyond Our Ken and Round the Horne. A great and much-loved raconteur, he was a regular and brilliant member of the Just a Minute team for nearly 20 years. He had earlier worked with Tony Hancock in Hancock’s Half Hour. Williams was a complex person with a serious side that embraced a great love of poetry and art.

WILLIAMS, STEPHEN (1908–1994). Williams was an important figure in commercial radio history before and after World War II. After spending time at Radio Normandy, he worked for Radio Paris at the time of the transfer of output to the fledgling Radio Luxembourg in December 1933. It was Williams who was responsible for the launch and early development of the station.

During World War II, he became the broadcasting officer for the Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA). Among programs he worked on from this time were Variety Bandbox and It’s All Yours. Returning to Luxembourg in January 1945, he became the first postwar director of the station when it relaunched. In 1948, he joined the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), where for 14 years he produced Have a Go. He was also involved in the establishment of BBC Radio Enterprises in the mid-1960s.

WILTON, ROBB (1881–1957). Referring to himself as a “comedy character actor,” Robb Wilton was already a star of music hall and repertory theater by the time he made his first radio appearance—on 2LO—in 1922. Born in Liverpool, he developed a rich strain of northern English humor that centered around a bumbling bureaucratic inefficiency. He became a major radio star in the late 1930s, and through the war years the British public found solace in his sketches and routines revolving around “muddling through”; by creating this loveable persona, he caught the mood of the nation. His last radio appearance was on Blackpool Night in August 1956. He died in May of the following year.

WINN, ANONA (1907–1994). Born in Australia, Anona Winn first trained as a pianist and then as an opera singer (under Dame Nellie Melba) prior to coming to Great Britain. She first broadcast on radio in 1928 in Fancy Meeting You. Widely known as a singer, composer, impressionist, and actress, she had made more than 300 broadcasts by the mid 1930s and had fronted her own dance band, “Anona Winn and Her Winners.” Postwar, her considerable fame rested mostly on her role as a panelist in Twenty Questions from 1947 and her presentation of Petticoat Line from 1965 (a program she also devised).

WIRELESS GROUP. The company, which owned the national commercial speech station TalkSport as well as 13 regional and local radio stations, was run by Kelvin MacKenzie, a former editor of the Sun newspaper, from 1998–2005, when the group was purchased by Ulster Television for £98.2 million.

WIRELESS PUBLICITY. Founded as a production house in 1936 by Radio Luxembourg, in premises on London’s Thames Embankment, Wireless Publicity was created, like its rival companies, the Universal Programmes Company and Universal Radio Publicity, to package sponsored programs for the station. As with its parent company, it was revived after the war, and in 1954, its name was changed to Radio Luxembourg, London.

WOGAN, TERRY (1938– ). Born in Limerick, Ireland, Terry Wogan’s first role in radio was with Radio Telefis Eireann (RTE) as a newsreader/announcer. After two years working in documentary features, he moved into light entertainment as a disc jockey and presenter of quiz and variety programs. His first job with British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) radio was presenting the Light Programme music show, Midday Spin, and when Radio 1 started, he presented Late Night Extra on weekday evenings. Later, he presented the afternoon program on Radio 2, in April 1972 taking over the breakfast show.

Wogan left radio for a period to concentrate on television, including Wogan, a chat show that ran for seven years on BBC 1 TV, three nights a week. It was, however, as a radio presenter that Wogan has been most celebrated. In 1993, he returned to Radio 2 to present the breakfast show again, this time retitled Wake Up to Wogan. A series of honors followed; in 1994, he won the Sony Radio Academy Award for the Best Breakfast Show in 1997, he received an OBE in the New Year’s Honors List, and in 2005, he was awarded an honorary knighthood, in addition to receiving the award for Radio Broadcaster of the Year at the Broadcasting Press Guild awards.

WOMAN’S HOUR. Founded by Norman Collins, creator of the Light Programme, in October 1946, it originally occupied an afternoon slot, 2:00 p.m.–3:00 p.m., a time conceived as being the one hour in the day when women at home would have time to themselves. The program’s format—a series of magazine items and studio interviews on matters relating to women, and a read serialized book (later dramatized)—has changed little, although the content has altered to reflect the altering role of women in society.

In 1990, Radio 4 moved the program—amidst considerable controversy—to a morning place in its schedule, where it has remained. Although its first presenter was a male, subsequently the program has been presented by a series of women, including Jean Metcalfe, Marjorie Anderson, Sue MacGregor, and Jenni Murray.

WOMEN. From the first days of UK broadcasting and the creation of the British Broadcasting Company (BBC), the role and perception of women both as broadcasters and listeners has been at once crucial and frequently contradictory. In the latter case, there was a long-held view informing policy among broadcasters that a man’s place was in the workplace while a woman’s was in the home, making her therefore an available audience for programs of a particular type and style. Early examples of men’s attitudes toward women within the medium show that they were frequently patronized and marginalized both as staff members and as consumers of radio, attitudes that reflected the Victorian roots from which the first broadcasters emerged. The first programs specifically aimed at women listeners had content that was suggested by a Women’s Advisory Committee, and the coming in 1946 of the long-running Woman’s Hour has seen an evolution of styles and attitudes, hosted by a succession of highly distinguished broadcasters, including Jean Metcalfe, Marjorie Anderson, Sue MacGregor, and Jenni Murray. At the same time, the existence of such a program has at times been criticized as a form of compartmentalizing women’s issues and ideas. The perception of a stereotypical image of the woman listener at various times was carried over into a number of broadcasting journals, including Radio Pictorial during the 1930s.

A number of serials and soap operas, such as Young Widow Jones, Mrs. Dale’s Diary, and Waggoners’Walk demonstrated media perceptions of women in society at various stages of British broadcasting history. In the field of light entertainment, Mabel Constanduros was significant during the 1930s in creating a unique voice for British radio comedy. Likewise, Elsie and Doris Waters, in the personas of their cockney characters, “Gert and Daisy” established themselves as a radio institution that survived for over 40 years.

The first woman announcer to introduce a program was Sheila Borrett, in July, 1933. A month later in the same year, the news was read by a woman for the first time, although this was discontinued soon afterward. It was not until 1974 that the news on Radio 4 was read by a woman (Sheila Tracy), and shortly afterward Sandra Chalmers and Gillian Reynolds became managers of BBC and commercial radio stations, respectively. Other distinguished broadcasters included Audrey Russell in the field of live commentary and Doris Arnold in music presentation.

Early and highly influential women producers included Olive Shapley, Nesta Pain, and Hilda Matheson, who were innovators and developers of radio techniques that were subsequently widely adopted. Nevertheless, the official prejudices within the BBC meant that there was little equality; for instance, if a woman staff member married a male who also worked for the BBC, the woman was required to resign from her post. The history of women in UK radio provides many examples of inequalities while demonstrating the major part played in all areas, including production, presentation, technical work, and management. In the modern BBC, Helen Boaden and Lesley Douglas—as controllers of Radio 4 and Radio 2, respectively—have significantly contributed to the development of radio in the UK, and Jenny Abramsky’s role as director of radio and music has been instrumental in steering BBC policy through major changes in the way radio is both made and consumed. Beyond the BBC, the diversity of women’s roles in modern society has been reflected in many ways, including feminist community radio stations, lesbian radio, and local Asian radio.

In general presentation, Annie Nightingale and Jo Whiley have achieved real status and authority in popular music presentation, while Jenni Murray has presented both news and specialist media programs, as has Libby Purves. Mary Somerville helped develop the BBC’s policies relating to educational broadcasting from 1925, and Bridget Plowden, in her role as chairman of the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA), was a key figure in the evolution of commercial radio within the UK.

WOOD NORTON. This medieval mansion in Worcestershire was purchased by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) in 1939 in order to relocate its broadcasting operations away from urban sites during wartime. A dozen studios were built, and within a year Wood Norton had become one of the largest broadcasting centers in Europe, averaging 1,300 radio programs a week. It was also, for a time, a monitoring station, with linguists tuning in to overseas broadcasts. After the war, Wood Norton became the BBC’s engineering training center. Purpose-built facilities in the grounds are still used for this.

WORKERS’ PLAYTIME. In 1940, the minister for labour, Ernest Bevin, requested that the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) devise a program that would support and cheer workers in factories supporting the war effort. The result was Workers’ Playtime, beginning as a weekend show in May 1941, and moving into a thriceweekly slot from October that year, when Bevin himself introduced the program. Hosted by Bill Gates, the program comprised variety “turns”—notably Elsie and Doris Waters, who were regulars throughout the show’s career in their characters of “Gert and Daisy” and two pianos, and was always transmitted as an outside broadcast from a factory canteen, the location of which was kept secret for security reasons during the war years, the announcement telling the listener only that it came from a “works somewhere in England.” It long outlived its original intention, the final edition under the original name coming from a factory in Hatfield Heath in October 1964, when guests introduced by Gates included Anne Shelton, Cyril Fletcher, and Val Doonican.

THE WORLD AT ONE. Created by Andrew Boyle, launched in October 1965, and hosted in its early years by William Hardcastle, The World at One, a daily half-hour news magazine program on the Home Service that was to continue on Radio 4, is an example of a policy, encouraged by Frank Gillard during his time as director of sound broadcasting at the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), and Gerard Mansell, of moving speech output away from scripted contributions and into the field of live debate.

WORLD RADIO. Almost as soon as radio began in an organized form in the United Kingdom, early adopters of receiver technology sought to experiment by exploring the airwaves in attempts to locate more and more distant radio stations. Within the context of this climate, the British Broadcasting Company (BBC) founded World Radio, initially the Radio Supplement, in 1925, two years after its domestic The Radio Times. Subtitled, the Official Foreign and Technical Journal of the BBC, its purpose was to foster awareness of international radio, and the journal contained articles and listings, together with wavelengths and broadcasting times. As the BBC moved toward its new Empire Service, the journal was expanded in 1932, in spite of objections from the trade press.

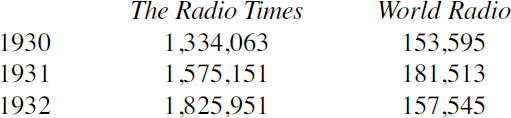

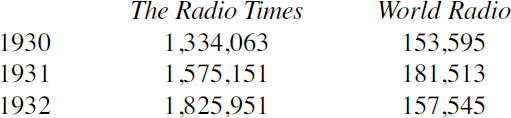

The interest in international listening during the 1920s and early 1930s gave World Radio its purpose; compared to The Radio Times, its circulation was extremely modest, as the following comparison demonstrates:

The year 1931 proved to be the highpoint in sales for World Radio, and thereafter sales diminished. The journal ceased publication in 1939.

It was a curious and ironic fact that in the first years of the 1930s, World Radio was carrying listing for stations, which themselves were supported by sponsorship, broadcasting from the Continent into the UK. As a BBC journal, this was inappropriate, while at the same time, the Corporation had commercial factors to consider in the sale of its magazines. Although most of the listings were terse and factual, occasionally a study of the pages of World Radio reveals a sponsor’s message, and toward the end of the journal’s life, it was carrying full details of Radio Normandy programs. It is no coincidence that Leonard Plugge, while developing his commercial radio interests, had gained a contract from the BBC itself “to supply, translate and sub-edit foreign wireless programs” for World Radio. See also JOURNALS.

WORLD RADIO NETWORK (WRN). World Radio Network was created in 1992 by three former British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) staff members who aimed to take advantage of emerging technologies to improve the distribution of international shortwave radio. The company’s first contract was to deliver programs from Vatican Radio to listeners via the Astra satellite. WRN then began to create its own branded radio channels carrying daily scheduled programs, many from international shortwave broadcasters. These channels were distributed to listeners via analog and later digital satellite, cable, the internet, and local AM/FM relays, enabling listeners to hear international radio in greatly improved audio quality, particularly in comparison to shortwave.

Channels were themed according to language, and WRN developed services in English, German, French, Russian, and Arabic. International broadcasters find in WRN a conduit for the daily or weekly dissemination of their programs in high-quality audio; these include Radio Netherlands, China Radio International, Radio Canada International, Deutsche Welle, and Radio Australia. Distribution has continued to develop as new technologies have offered themselves, among them podcasting, Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB), and mobile telephony.

In recent years, the company has taken advantage of its aggregation and distribution infrastructure to offer a wide range of transmission services to other broadcasters. It also developed an extensive brokerage service, buying time on shortwave, AM and FM transmitters on behalf of clients.

WORLD SERVICE. From the early days of the British Broadcasting Company (BBC), there was interest in creating a broadcasting service that could link the British Empire. The development of shortwave was a key element in this technically, and although the main advances in this were during the 1920s, the BBC was not financially in a position to undertake this. Given that the license fee provided UK listeners with a service, John Reith initially argued that the British public should not be required to fund a service beyond the domestic confines of broadcasting. This view was reversed in 1931, as in the throes of a financial crisis, the creation of such a service was deemed to be in the national interest. On 19 December 1932, the Empire Service was opened, and on Christmas Day, King George V spoke to the Empire for the first time.

The service operated through five separate two-hour transmissions at different times of the day, aimed at specific areas of the world. Gradually, transmission increased until by September 1939 the service was operating 18 hours a day. Programs were frequently rebroadcasts, or relays of domestic shows, although from 1934, there was a specific News Department. The first programs broadcast other than in English were those of the Arabic Service, which began January 1938; later the same year, broadcasts in French, German, and Italian were added, countering the increasing number of propaganda broadcasts coming from Europe at the time. Wartime broadcasting saw a very considerable development of overseas broadcasting from the UK, and it was to accommodate this that the BBC took over the J. Walter Thompson radio studios in Bush House, London.

It was during the years 1939–1945 that the title “Empire Service” was abolished, and was replaced by the General Overseas Service. With the election of a postwar Labour government, the decision was made to continue the multilanguage services that had been established, funded by the government, but with content decided by the BBC. This was the basis upon which the newly titled “External Services” were built and the key element that has established the global uniqueness of the service itself.

The postwar years were, however, difficult: with spending cuts brought about by economic depression, and a serious confrontation between the Anthony Eden government and the BBC over the 1956 Suez Crisis, during which the BBC’s determination to broadcast both sides of the argument raised for a short time the possibility of the BBC coming under direct government control. Other issues emerged with the development of the Cold War with the Soviet Union, and the reputation of the BBC for impartial reporting of world events at a time when propaganda continued to be rife, was a major factor—together with the application of the transistor to receiver technology—in growth in listenership. In 1965, the General Overseas Service was renamed “The World Service,” and in 1988, the title was extended to include all External Services of the BBC.

In 1991, the World Service moved into television and today broadcasts as BBC World. In radio, the development of satellite technology has enabled frequency modulation (FM) relays in many areas of the world. Added to this, in 1995, the BBC’s Polish service was the first to go online, and this subsequently increased to cover all 43 languages covered by the service in addition to English. The World Service now broadcasts 24 hours a day in English and for varying durations in its other languages.

WRIGHT, STEVE (1954– ). Joining Radio 2 in April 1996 as part of the redesign of the station instigated by controller, James Moir, Steve Wright initially presented two weekend shows, on Saturday and Sunday mornings, but later moved to weekday afternoons, while continuing with his Sunday Lovesongs program. Born in Greenwich, London, he first joined the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) as a researcher and record librarian, leaving in 1975 to work briefly in European radio. Thereafter, he made programs for the London Broadcasting Company (LBC) and then Thames Valley Radio (Radio 210) in 1976. Three years later, he was at Radio Luxembourg and then joined Radio 1 in January 1980, where he presented various shows.

In January 1994, after a highly successful period as the afternoon program host, he took over the breakfast show, where he remained until 21 April 1995 when he resigned in dramatic fashion in protest against the reforms on the network then being undertaken by Controller Matthew Bannister. Wright has won a wide range of awards for his work in UK music radio.

WRITTLE. Situated near Chelmsford in Essex, home of the Marconi Company, the village of Writtle was the location of the first regular public broadcast program in the UK, which commenced in February 1922. The circuit was almost identical to that of a standard Marconi telephone, and the transmitter fed a four-wire aerial 250 feet long and 100 feet high, originally radiating on a wavelength of 700 meters.

The equipment was housed in a former army hut, and the station took the call sign 2MT, Two Emma Toc, broadcasting a weekly half-hour program of technical information, testing, occasional music, and entertaining banter, principally from its main presenter, Captain P. P. Eckersley. The station closed on 17 January 1923. Writtle remained a company site for many years thereafter. The historic hut was later removed for use by a local school but was subsequently retrieved and is now housed at the Chelmsford Science and Industry Museum, Sandford Mill. The site of the hut is today commemorated by a nearby information board at Melba Court, named after Dame Nellie Melba, who made Britain’s first entertainment broadcast from the company’s New Street works in Chelmsford (See “MELBA” BROADCAST). The board was unveiled in 1997 by Marconi’s daughter, Princess Elletra Marconi. The site itself was sold, and the land was used for housing development in the 1990s.

In the village of Writtle, the Church of All Saints contains a window commemorating the work of Marconi. It was dedicated by his grandson, Prince Guglielmo Marconi Giovanelli, in 1992. The Writtle station may be seen as the true birthplace of UK radio as a public entertainment form.