CHAPTER 11:

BREAKING AWAY: EXPLORING NEW NICHES

There are any number of reasons photographers leave one area of specialty for another, or add a new specialty to their existing one. The realities of their market may cause them to steer their careers away from the type of images they feel passionate about, and so they come back to their desired subjects and styles later in their lives. They may love the subject matter/images they get to create but dislike the particular industry or marketplace in which they are forced to compete. Their market, interests or the economy might change and force them into new areas. They may lose the physical stamina required for location work and turn to studio photography. They may crave a new creative outlet and new challenges.

AND NOW FOR SOMETHING COMPLETELY DIFFERENT — OR SOMEWHAT SIMILAR

Entering a new niche doesn't have to mean switching from underwater fish photography to weddings or from architecture to head shots. Often the change is much less extreme. A wedding photographer, finding his market suddenly crowded with upstarts willing to give away copyrights, might make a shift into lifestyle shooting — an area that requires a similar style and the same equipment but sells to a different market with a different fee structure. For a period of about five years I added child commercial shooting on top of my child portrait work — same subject but different market, fee structure and style. An architectural photographer may keep shooting editorial work for design magazines but also market to commercial architectural suppliers — same work, different market. Often finding a new niche involves some tweaking, not wholesale changes.

Ibarionex Perello fuses his talents for portraiture, storytelling, and street photography to create portraits of California Poets. This is Gar Anthony Haywood.

WHEN TO MAKE THE MOVE

It doesn't matter whether you're in the beginning, middle or later stages of your career — if your existing market falters, if a golden opportunity presents itself or if your heart wanders in a new direction — you should follow your gut. Of course, changing or adding new niches will create different pros and cons depending on what career stage you're in. A change at the beginning of your career, while it may prove necessary, will probably be extra difficult, given that you'll still be in the learning stages regarding both your art and your business. But on the pro side, you're young, you're supple, you're energetic and you're willing to do anything to succeed. You don't yet have a huge ego involvement or emotional tie to your original area of specialty, so you're freer to try new markets.

Making the change in your business' midlife can come with a bigger emotional price tag — you're committed to your specialty and your business is probably still appreciating significant growth, even if your market or the economy is failing. So making a change at this stage of life is cause for pause. Is this really necessary? You'll have your doubts. On the other hand, you're well into your career, and while the learning never really stops, you've got enough experience and enough resources behind you to make this kind of a transition easier.

Doug Beasley's fine art images are well received by his corporate and commercial clients, like this one of Torji Gate, Miya Jima.

Changing niches late in life can be a godsend or a heartbreak, depending on the motivation for the change. If you're making the change to pursue your dreams and make the images you've always imagined you'd one day make, then it will be easy. But if you're a well-established shooter with a glorious career whose market suddenly dries up and forces you to start over in some new niche, well, that's heartbreak. You're used to being a big dog; now you're practically starting over with the little dogs again. But there's a hidden plus here: Once you get over the angst, you might actually like starting over. Some of that good wholesome fear, that thrill of the unknown that you had at the very beginning, might come back. It could provide a new lease on your creative life.

CRAIG BLACKLOCK: A NATURE PHOTOGRAPHER MAKES A NATURAL TRANSITION

Craig Blacklock's late father and partner, Les, was one of the pioneers in the field of nature photography. When Craig joined his father in 1974, they were like kids in a candy store, shooting anything and any place they desired. There was always someone out there willing to pay top dollar for their images. While they didn't take assignments, they did keep their audience always in mind. “To be an artist is not just making yourself happy, it also means communicating with your public through your images,” says Craig.

Blacklock creates two different kinds of images for two different kinds of art appreciators: “I have my more abstract work, which people buy for its artistic merit and as an investment. And I have my more literal work, which appeals to people who appreciate it for its regional value — they spent part of their summer on Lake Superior and they want to extend their vacation.”

As the nature field became crowded and its practitioners increasingly disregarded standard industry billing and copyright protocol, it became very difficult to earn a living. Blacklock loved and cared deeply about his subject matter, so he wasn't about to give up nature photography. But he responded to the grim realities of the industry by creating new markets for his work.

“I opened two art galleries: Waters of Superior and Blacklock Gallery,” says Blacklock. Thus he created his own retail market for his fine art photos. And as the calendar market faltered, with fees for images dropping up to 65 percent, Blacklock began to publish his own calendars and books. “I still sell images for editorial use and to designers and corporate art consultants, the people who do interior design for places like hospitals and banks. And I'm with Larry Ulrich Stock Photography, Inc. But to continue to thrive in this field, I've had to add to the ways I sell my images.”

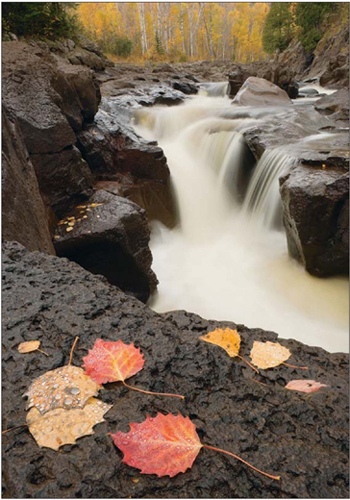

Craig Blacklock's fine art nature images sell well as decorative art for hospitals and hotels.

By applying his creativity to his business as well as his art, Blacklock has managed to thrive and to maintain his integrity in an increasingly difficult market. He has found a large high-paying niche in artwork sales to institutions, with the surprising addition of nature video sales.

“The biggest upside for me has been hospitals and hotels buying large numbers of prints. I am now complementing that work by doing nature videos that are played in hospitals. This is a niche I've worked in for many years, and now that many hospitals are remodeling or expanding, they're using more video — it is really paying off. Some sales have come in directly, but most sales come from art consultants that take 40 percent of the sale — and they are worth it! I've worked with some of these consultants for around thirty years. I always try to deliver ahead of schedule, and they know they can trust that when they place an order, their client's expectations will be exceeded.”

Blacklock's large increase in sales to institutions has helped offset a drop in his sales to individual photography collectors, though there are still a few serious collectors buying large numbers of prints. And this has also served to offset the dwindling market for fine art books and stock images.

“Over the past decade or so I've put more and more emphasis on my print and self-published book sales. Stock continues to sell but is a very small part of my overall income. The biggest change recently has been the drop in high-end book sales. Last year I came out with a $60 book that included a three-hour DVD. It was a good value, reproduced very well, won awards and got many good reviews, and the movie played on public television. But the economy tanked, and with it, high-end book sales.”

VIK ORENSTEIN: SAME BAT TIME, DIFFERENT BAT CHANNEL

I opened up my first studio, KidCapers (then called KidShooters) in 1988. My portrait prices were by necessity higher than those of studios that specialized in direct color or even standard black-and-white work because of the labor intensity of creating hand-processed, hand-painted fine art prints. My average client spent over $2,000 at that time on a photo session, portraits and frames, and I developed a reputation for being expensive.

Even such a seemingly straightforward specialty such as portraiture can be established in a variety of niches, from point of purchase to retail; from wall art to photobooks; from fine art prints to machine prints. Here's one of my portraits.

The reality, though, was that I offered my hand-painted portraits at a price substantially lower — per portrait — than my closest competitors. The myth that my studio was expensive arose from that high average purchase; it wasn't that my portraits were more expensive, it was that my clients made bigger purchases. For clients who both desired and could afford the best, this was no problem. But my friend and at that time, employee, Pat Lelich, noticed that quite often we were losing clients because of this perceived expensiveness. Since it wasn't possible to offer our current product at a lower price and remain profitable, we became partners in Tiny Acorn Portraits, Inc., and opened our first retail studio in 1994. Tiny Acorn portraits were still custom hand printed and hand colored, but we eliminated much of the labor by simplifying the product. The prints were not sepia-toned and were not otherwise stabilized, so were not strictly archival. The coloring was done with transparent watercolor pencils rather than artist's oils (oils are more difficult to manipulate and take much longer to dry), and we offered pre-made frames rather than the extensive custom design and framing services offered at KidCapers. The result was a product that we could sell for nearly 50 percent less than the product at our original point of destination studio.

A popular category for stock is “funny animals.” This one is by Jim Zuckerman.

At first there were a lot of doomsayers. “You're competing against yourself!” “Everyone will go to the cheaper, more visible and convenient retail studio and no one will come to KidCapers anymore!” and “Are you crazy?” were some common comments.

I didn't feel I was competing against myself at all, though the portraits offered at both studios were hand painted, the similarities stopped there. Each business had a different niche, a different price point and therefore a different client base. (Although it's true, there was some client overlap.) Only time would tell. At the end of the first year, the Tiny Acorn the first year, the Tiny Acorn Studio had paid back its initial start-up costs and was even nominally profitable — a really successful start, in my book. And during that year KidCapers enjoyed the same growth rate of 20 percent that it had for the previous four years. So the doomsayers were wrong. Tiny Acorn Portraits was a legitimate new niche. Sure, it looked similar, but ultimately it proved to be different.

Tiny Acorn Portraits became such a successful business that in August of 2008, I was able to sell it to a current and a former employee who now own and operate it. I continue to own and operate KidCapers Portraits. Both businesses are successful.

KAREN MELVIN: ARCHITECTURAL INTERIOR PHOTOGRAPHER CREATES A MARRIAGE OF CONVENIENCE

An interior photograph by Karen Melvin.

When Karen Melvin started her career in architectural photography, she marketed herself primarily to local architecture firms and magazines. She also marketed to local hospitals, banks and any institution that might need architectural images. For the most part, she focused on generating editorial work. While the editorial field in general offers better than average creative freedom and prestige, typically editorial rates are far lower than commercial rates.

So eventually Karen started to market her work nationally to product manufacturers such as window and tile companies who supply architects and builders. The results thrilled her. “This niche pays more, and there's a bigger client base to draw from. There's more production value, more legwork — and I love that part!”

Karen still shoots editorial work that winds up in such acclaimed publications as Architectural Record. She has successfully wedded her editorial and commercial specialties. But more and more, her work is in advertising.

Any regrets?

“Only that I didn't plumb this niche earlier,” Melvin says.

ROY BLAKEY: COMMERCIAL PORTRAIT AND FINE ART PHOTOGRAPHER SHOWS NAKED AMBITION

After teaching himself photography in the army (he bought his first camera in the PX [post exchange store] in Germany) and traveling the world as a professional ice skater in the touring show “Holiday on Ice,” Roy Blakey came to live in New York in 1967. He began his photography career shooting head shots for actors, dancers and models. “It was wonderful. I was the very person for it because I cared so much about these people and about making them look their most beautiful.” Blakey shot his share of celebrities, including Chita Rivera, Tommy Tune, Felicia Rashad, and Debbie Allen. Eventually his work wound its way into such magazines as Time and Gentleman's Quarterly. He loved his work and yet there was a new fine art niche he wanted to try: the male nude. “There was no market for it, obviously. When I had a body of work I started calling editors to see about getting it published. They told me I was crazy,” recalls Blakey. So he self-published 70s Nudes in 1972. He presold all five-thousand-plus copies he had printed. Exactly thirty years later — to the day — the book was reissued to critical acclaim. Referring to the fact that his subjects were dancers and models at the peak of physical condition, Blakey says, “We used to joke that the book should be called, Blakey's Bird's Eye Boys — Frozen at the Peak of Perfection!”

Blakey's foray into this niche was made early in his career. After his initial print run sold out, he stored his nude photographs in boxes, forgotten until another fine art photographer found them and encouraged Blakey to find a publisher to reissue them. While the huge majority of Blakey's career was — and still is — spent making commercial head shots, his brief detour into the world of the fine art male nude gave him a new creative outlet and a place in the history of fine art photography.

ROB LEVINE: PHOTOJOURNALIST AND COMMERCIAL PHOTOGRAPHER — FROM STAFF EMPLOYED TO SELF-EMPLOYED

Rob Levine began his career in 1983 as a photojournalist, working on staff for the Minneapolis StarTribune. Now he is self-employed, sharing a warehouse studio with another photographer, and shooting publicity and commercial images. He also hosts websites where photographers can display and sell their images, including stock, and he sells studio management software through GripSoftware.com. While it was Levine's dream to be a photo journalist, the realities of working in the industry left him cold. “I just didn't feel they were treating me very well,” he says. When asked why he didn't try to work for a different newspaper to see if working conditions were better elsewhere, he says, “Because the StarTribune was one of the best in that regard.”

Rob Levine eased naturally from photojournalism into editorial photography, creating images like this one for the Minneapolis Children's Theater Company.

Far from the gritty, grainy black-and-white images of his earlier specialty, Levine now shoots incredibly colorful high-resolution publicity stills for the Children's Theatre Company of Minneapolis, Minnesota. He gives this client maximum bang for its buck by hosting their website. “The site contains literally hundreds of media contacts. People can sign in to browse or use the images, and when there are new pictures, we send out e-mail notifications to the whole list. It's a very efficient and cost-effective way of publicizing the theater.”

While Levine is passionate about his career as it is today, he says his heart is still in photojournalism. “It's all about going out alone, and I love going out alone,” Levine says. “But I'm very happy with my career now. I have no regrets.”

Leo Kim had worked for years in macro and landscape photography. When an illness forced him to stay in his home more than he liked, he found compelling subjects to photograph right in his own kitchen, and now he creates decorative wall art.

RANDY LYNCH: A PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHER GOES FORENSIC

When Randy constructed his home in 1990, he built in a home studio. His intention was to shoot portraits there — and for a while, he did. He also took a job as a forensic photographer with a county sheriff's department. The home studio became a playroom for his kids, never to be used again.

Randy is a genuine, extroverted people person. You can see how he'd be successful at portraiture and every aspect of that business. But when he talks about his experiences as a forensic photographer, he gets fire in his eyes. Words like nanometer, omni chrome and luminal sprinkle his speech, and he's too engrossed with his topic to notice that those who are listening might get lost in his dust.

I asked him if it didn't get boring, taking hundreds of pictures of one pair of jeans, each with a different filter, trying to illuminate blood or semen stains.

“It's never boring,” he states emphatically. “When you find blood or semen, you've helped to stop a murderer or a rapist. How can that be boring?” Randy worked for the sheriff's department for ten years and ultimately left because of political and personality issues within the department. “If it weren't for those issues, I'd still be working there today. I loved it.”

But just as his issues with his forensic job were coming to a boil, he was offered an opportunity to buy into a photo lab in the busy Minneapolis skyway system.

“It was perfect,” he says, “because there's one big crunch time when everybody drops offor picks up their film in the skyway, and that's lunchtime, so that's when I'm at the lab. The rest of the time I spend visiting commercial clients and taking care of business.”

Randy also has established himself in a third photographic niche — he shoots weddings.

“Nobody ever asks me for the negs,” he says, “because I'm their lab! A lot of my wedding clients are my regular lab clients, so I've printed their work for them for years.”

These are some great success stories. But trying a new niche is no guarantee of a happy ending. I once tried to offer a less expensive direct color product at KidCapers Studio. Not only did no one buy it — not one family — but the very existence of this new product confused some of our clients and spurred rumors that the studio had gone out of business.

And you'd think that going from a huge, glamorous market like New York to a medium-sized market would be a breeze — that your little niche would be right there waiting for you. But when Roy Blakey brought his head shot business from New York to the Midwest, “It took forever for people to catch on to me. They all knew Ann Marsden (the reigning head shot queen of the time) and no one knew me. But I stuck to it, and now it's back to business.”

GUARANTEE? WHAT GUARANTEE?

While adding or changing to a new niche is no guarantee of a heftier income, there are precautions you can take that will increase your chances of success:

• KEEP YOUR FINGER IN THE PIE. This is the photographer's mid-career equivalent of the warning, “Keep your day job!” Don't drop your original specialty until your new one has proven lucrative enough to warrant it.

• DON'T ROB PETER TO PAY PAUL. Do not, I repeat, do not enter into a new niche if doing so requires that you take needed resources away from your original one. If becoming a dirt bike–racing photographer requires you to buy equipment with money you would have otherwise used to send out your spring portrait mailing, don't do it. Or if going out and becoming a field photographer leaves no one at your studio to answer the phone, forget it. The risk won't be worth it.

• CATEGORIZE YOUR NEW NICHE. Is it a simply a new product you can offer at your old studio or a whole new business that requires a new venue and identity? Is it an entirely new specialty area or just a different market for your current work? Is it a different product for your existing client base or a similar product for an altogether different client base? Once the answers to these questions have solidified in your mind, you'll be better able to create a business plan, just as if you were starting out from scratch, as outlined in chapter five.

• QUESTION THE MASS MIGRATION. When your market becomes saturated and other photographers head for greener pastures, you might want to stay put and bide your time. You may find yourself (happily) alone in a suddenly less crowded specialty.

You can see the logic in the progression of the niche-jumping photographers whose stories I've shared with you in this chapter. That's because their stories have already happened and we know how they come out — that's called twenty-twenty hindsight. If you're contemplating a similar leap, you don't have the luxury of knowing whether you'll have a happy ending. But then again, neither did they.