CHAPTER 12:

CALCULATOR MAGIC: PRICING YOUR WORK

Within the different specialties of photography, there are very different fee structures and methods for pricing work, but photographers in every discipline share one characteristic: We have all, at one time or another in our careers, charged too little for our work, or we've given up usage rights and copyrights for little or no compensation.

To be fair, it's not just photographers who have trouble exacting their fees. I think its common among entrepreneurs and self-employed people across the board. I have a psychologist friend who jokes that she's going to teach a seminar for other psychologists that will consist of nothing but three days of repeating the same phrase over and over: “That'll be $200, please.”

Fine art/commercial photographer Doug Beasley says, “It's somewhat arbitrary. I make up a number. Sometimes I check it against the ASMP (American Society for Media Photographers) guides and it's usually pretty close to what their standard is. I simplify the process — figuring out usage can be so complicated. I give away more rights than I should, but I'd rather live that way than live in fear of being ripped off.”

Fashion/commercial shooter Lee Stanford credits part of the success and growth of his business to his ability to become savvier about charging for usage and setting his prices. “I used to give away too much. Now I go by the industry standard, and no one flinches. I think clients expect to pay for good work, and they don't appreciate you any more if you give it away than if you charge a fair price.”

Though usage fees don't often come into play in my portrait business, there are gray areas when a portrait client wants to use a portrait for a business application, or a business owner asks to sneak in a few portraits of her kids during a commercial shoot. Early in my career, I just swallowed my tongue — and the monetary losses — and allowed my clients any little favor, even if it violated my copyright. But now I, too, go by the book.

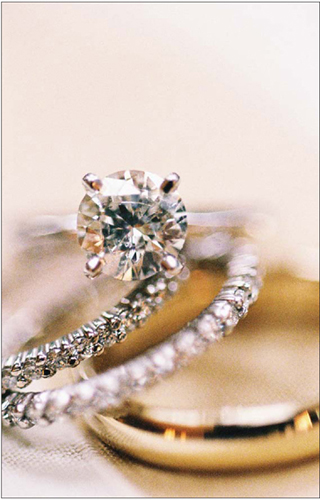

Most clients want to receive their digital files along with any photo albums, photo books and prints they order, so photographers like Hilary Bullock tend to charge an up front fee that includes the shooting fee, a photo book, and DVDs of part or all of the images.

HOW TO SET YOUR FEE STRUCTURE

Fee structure and pricing are entirely different animals. Fee structure refers to what the client pays for and when he pays it. For instance, this is the fee structure for one of my studios: The sitting fee is required at the time of the booking; the cost of the sitting is determined by the number of subjects; the sitting fee covers expenses (the client doesn't pay extra for film, processing, proofs or anything else); the portraits are payable 50 percent upon placement of the initial order and 50 percent upon delivery.

That's my fee structure. Notice that there aren't any dollar amounts in there — that would be my price list.

Fee structures vary markedly from one area of specialty to the next. My fee structure is fairly standard for portrait studios. But a standard commercial shooter's fee structure would go something like this: A commercial photographer charges a standard day rate. The client pays the photographer's fee by the eight-hour day — usually there is a half day minimum; the day rate will fluctuate based on the usage of the photos (higher exposure usage results in higher shooting fees); the client pays for materials and expenses, usually with a 15 percent markup.

You can see that a commercial photographer's fee structure is decidedly different from a portrait photographer's. Each different area of specialty will have its own little quirks in its way of billing for services.

You need to find out what the standard is for your specialty in your geographic location, and use it with integrity.

PRICE STRUCTURE

Your price structure refers to what you charge for your products and services. Here's the price structure for one of my studios: The basic sitting fee starts at $145; a black-and-white 5″ × 7″ (13cm × 18cm) portrait costs $89; a hand-painted 20″ × 24″ (51cm × 61cm) costs $850, and so forth. A commercial shooter's price structure might look something like this: A basic day rate is $2,500 for limited usage; higher exposure usage doubles the day rate to $5,000; travel time is billed at 50 percent of the day rate.

How do you know how to price your work when you're just starting out? First, you want to find out what your industry and market standards are. That is, what are other photographers who work in your city charging in your area of specialty?

PROFESSIONAL ORGANIZATIONS

One way to get up to speed fast is to join a professional organization like the one Doug Beasley mentioned earlier — American Society for Media Photographers. Not only do members receive a wealth of information on all aspects of the business, including how to figure usage charges, they also hold monthly meetings on issues like this very topic. If you attend these meetings, you can network with the people in the business, find out what they're charging and get a feel for the pulse of your market.

If you're a portrait photographer, you might consider joining Professional Photographers of America (PPA). They have a beautiful monthly magazine that covers all aspects of the portrait photography business, including creative, technical and business.

APPRENTICESHIPS, INTERNSHIPS AND ASSISTANT WORK

Of course one of your goals, if you do an apprenticeship or work as an assistant, is to learn this aspect of the business. Remember the advice of our seasoned photographers: Don't just learn how to set up lights when you assist — learn it all. When you work with an established photographer you get to see the how they put a price on their work, when they flex on a fee and when their fee is nonnegotiable.

Fashion photographers like Lee Stanford generally charge a day rate that averages from $1,200 to $8,000 depending on your market. Editing/retouching and archiving may be built into the day rate or may be charged separately.

INFORMATIONAL INTERVIEWS

Informational interviews can be instructive in setting up your payment structure. You can also phone a few shooters and/or their reps and inquire about their basic day rate. Some may give you this information up front. Others may hesitate to make a blanket statement, preferring to make bids on a job-by-job basis.

PICK UP THE PHONE OR CRUISE THE WEB

Often photographers in portrait or wedding photography list their fee structures and prices on their websites. If they don't, try e-mailing them or calling on the phone to ask for pricing details.

Whatever you do, level with the businesses you approach. Sometimes people who are learning the market with the intention of starting up their own shop call my studio and are afraid to tell us they are our would-be competitors, so they pretend they're potential clients.

Generally we can spot them right away, and this approach makes my coworkers and me feel extremely disrespected. We are more than happy to send out information to anyone so there's no need to invent stories. Our pricing is public record — it's no secret.

Speaking of secrets, some shooters, even seasoned established professionals, “secret shop” the competition from time to time. This is an especially common practice for national chains. I guess they like to see what we little guys are up to.

I have personally been shopped by three local photographers and one national studio, Lifetouch Inc. (They revealed their shopping trip to me and shared their impressions with me.)

I have never employed this practice, although I have been tempted. It is intriguing to find out how other people work.

BARGAIN BASEMENT, CARRIAGE TRADE AND EVERYTHING IN BETWEEN

Once you've discovered what the range is for prices in your market, you need to decide where within that range you want to position yourself.

Let's say you're an architectural photographer in Minneapolis. There are established shooters — people whose names you see on photo credits in local magazines — whose day rates range from $1,200 to $2,000 for editorial work, with the average falling around $1,600.

This macro nature image by Brenda Tharp could sell as stock and/or as decorative or fine art prints. The same image can be resold, so it's possible for a single successful image to make a lot of money for the photographer.

“I'm new,” you think, “I'm just breaking in, so I should come in under the market, let's say at $800 or $900 per day, just until I get established.” But that could be a bad idea for several reasons.

PERCEIVED VALUE

If your billing rate is below market, potential clients will think your work is below market quality. This is because your prices tell the client how to perceive the value of your work.

It's different when you're selling a television, for instance. The television has an established value; it sells for $500 at a big electronics store. If the television goes on sale for $425, the consumer will be ecstatic! He'll know he's getting a great deal because he is getting a television that's worth $500 for $75 less. Your work has no established value, other than what you charge for it. Your clients have no other way to appraise it, unlike the television.

“The client is probably not looking for the cheapest deal,” says Pam Schmidt, a former photographer's rep turned art buyer. “Usually they want someone whose estimate falls somewhere in the middle. Low-ball bids give the impression the work will be poor quality, and high-end bidders just aren't for everyone. There are clients who are simply price shopping — they're not concerned about quality, they just want a deal. But in my experience, you really don't want to be working with those guys. They want more for their dime than a regular client wants for their dollar, and they're really aggravating.”

So where should a newbie position herself on the pricing ladder?

“Somewhere on the lower end of the middle — using your example range, I'd say just under the $1,600 mark. Don't go for the low end, or not only will your perceived value be less but you'll be competing with a huge pool of shooters. Remember, it's crowded at the bottom. And don't go for the high end, because you can't justify that — at least, not yet — and you'll take yourself out of the running for a lot of jobs,” says Pam.

It's different for retail studios because their location gives them a certain perceived value, a niche. For instance, my Tiny Acorn Studios offer a hand-colored 8″ × 10″ (20cm × 25cm) portrait starting at $79 — much below what you'd expect to pay. But because the studios are located in high-end boutique-style shopping areas, the product doesn't strike our clients as cheap, it strikes them as a boutique product at a shopping mall price.

Perceived value as it affects your market position is an important factor to consider when pricing your work, but there are many other concerns to add to your equation, too.

COGS, FIXED OVERHEAD AND YOUR TIME

All your expenses including start-up, COGS (cost of goods), fixed overhead, pass-through and your own time, need to inform your pricing decisions. You have to charge what you need to stay in business, or you won't be in business for long. I hear from many people who say, “Oh, I'd just be doing this anyway as a hobby, so if I just mark up the costs of my prints a little bit, I'll be fine.” But as Stacey King, fledgling wedding photographer discovered, that isn't often the case.

“When I first started shooting weddings, I thought I was really going to rake it in just by charging my clients $20 per hour and a 100 percent markup on my prints,” Stacey says. “I thought I was going to make an outrageous fortune. I felt so magnanimous I was throwing in extra shots for free — after all, heck, digital capture is free, right? But when I revisited my first three jobs, I realized that not only wasn't I making any money, I was losing it! I had forgotten to figure in things like gas and mileage, recovering my initial investment in equipment, the costs I had to eat when brides ordered shots they didn't pay for, my dedicated business phone line, office supplies … you name it. It all seemed so insignificant at the time, but oh, baby, does it add up!”

PRICE POINT APPEAL

There's a whole psychology to pricing that could be the topic of several books all by itself. For some reason, $19.99 sounds cheaper than an even twenty. And 10 percent off gets just as many people just as excited as 15 percent off — but up the ante to 20 percent and watch them come out in droves. Two sweaters for the price of one doesn't bring out as many shoppers as “Buy one, buy the second one for a nickel.” I don't pretend to understand it. Sometimes the human animal is just a mystery.

I never worried about price point appeal when I opened up KidCapers Portraits. I was running on caffeine and blissful ignorance. But six years later, when I opened my first Tiny Acorn Studio, I had a specific price point in mind that I thought would be especially attractive to my client base: I wanted to offer a hand-colored 8″ × 10″ (20cm × 25cm) for $49. That sounded like such a deal! A hand-painted portrait for under $50? Amazing! So I went at the whole pricing process backwards — instead of figuring out my COGS, fixed overhead and time, and basing my prices on that, I noodled my expenses around to fit.

OH, THE DRAMA OF IT

Given that money is a very sensitive, emotional issue for many of us — photographers as well as clients — how can we make these transactions easier on everybody?

• GIVE ALL THE BAD NEWS UP FRONT. Hiding or downplaying costs may get you a client, but it will never keep one. It'll be easier to collect your fees and you'll stay on good terms when the job is done if you give your client all the bad news up front. Reveal all fees that the client might incur in the process of his shoot. For instance, at all my studios there is an extra charge for the painting of additional figures in a portrait. Each subject after the first costs an additional amount. So, if the basic cost of an 8″ × 10″ (20cm × 25cm) is $50, and each additional subject is a $15 painting fee, then an 8″ × 10″ (20cm × 25cm) with three kids in it would cost $80: $50+$15+$15. We tell our clients about the additional painting charge before they book their photo session. It's also stated boldly on our price lists and in our promotional material. This way the client never gets any rude surprises — and neither do we.

• KNOW THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN BIDS AND ESTIMATES. In order to be considered for a job in such photographic specialties as commercial or architectural shooting, when the photographer is in essence acting as a contractor for the client, he will be required to give either a bid or an estimate of how much he will charge for the job. A bid is generally “written in granite.” Here's a sample bid situation: Winsome Woman Magazine needs six outline shots for their May issue. Stanley Kowalski figures out what he thinks his time and expenses will be to do the job (if he's smart he adds 10 percent on top of that, because after all, surprises happen), and he agrees to shoot the job for that amount. That's it — if it rains and he gets stuck on location with a trailer full of rental equipment and damp talent, tough cookies. He eats the extra costs — he may even wind up taking a loss on the job. But if he gets lucky and gets the job done in half the time and half the material costs, he still gets paid the amount of his original bid.

An estimate is a little different. Stanley figures it will take him two full days to shoot at $1,600 a day. Archiving and post processing will run $450. Any bad weather days will cost $800. So Stanley's estimate for the job is $4,080, give or take a rain day. Technically, because this is an estimate and not a bid, Stanley is allowed to have his final bill come in at up to $4,488, or 10 percent more than his original estimate Conversely, if Stanley gets the shots he needs in only one day and half the material costs, he should only charge the client $2,040.

• GET IT IN WRITING. Never make a deal on a handshake. No matter how good intentions are, misunderstandings can and do crop up even with clients with whom you share a long, happy relationship. Having a written agreement doesn't imply that you think your clients are going to try to cheat you, anymore than the person who takes out a life insurance policy thinks he's going to die prematurely. It's simply insurance. Just create your estimate or bid on paper with the parameters of the job and the terms of payment clearly explained. Sign and date the document, and ask the client to sign and date it upon acceptance.

• BILL FOR PARTIAL PAYMENT UP FRONT. Believe it or not, this practice benefits the client as well as you. Obviously, it helps you insure that you'll receive at least partial payment, and it also helps you cover your expenses up front. But it also helps your clients with budgeting when the payments are spread out over time. It's human nature to put off until tomorrow what you can pay today, but when the final bill comes, it can be a nasty reality. Paying bills is sort of like childbirth — after it's over, we forget the pain. So if a client pays you $500 up front for a $1,000 job, he forgets the ouch from that first $500. And after the job is done, and he gets his final $500 bill, it hurts less than that $1,000 would have.

Leo Kim sells his macro food images as 3″ × 3″ prints in classic gallery frames for about $20. He also sells them for stock through various agencies.

DON'T APOLOGIZE

I don't know many people who feel comfortable asking for money on their own behalf. It's almost always uncomfortable. But whatever you do, don't apologize! Don't shirk or cower, or say, “I'm sorry, the bill is $450.” It goes back to perceived value: If the client thinks you don't believe you deserve your fee, he won't, either. You did an honest job, and you collect your honest fee. Period.

DON'T GIVE AWAY THE INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY FARM

It's always been difficult to protect intellectual property, and never more so than now. While more and more photographers are giving away their copyrights, it's more important than ever not to join the pack. Not only will you be losing money on the reuse of the images you give away, you'll be devaluing the quality of your work (your images could be reproduced shoddily and nonetheless they will still represent your work), and you'll be devaluing your own image (you'll be perceived as a bargain basement shooter and clients who are looking for the best photographers won't hire you).

Stick to your guns when it comes to retaining the rights to your images rather than offering complete buyouts. It can be hard during periods of bad economy and when your market is crowded, but in the long run, everyone will be better off.

WHEN A CLIENT VIOLATES YOUR COPYRIGHT

Don't assume that every copyright infringement is intentional — sometimes it results in a lack of knowledge on the part of the client, and sometimes, as when the client is a large corporation, it's a simple case of one hand not knowing what the other hand is doing.

If a client violates your copyright agreement, what should you do?

I recommend taking action but giving the client the benefit of the doubt. When you approach them the first time, leave your big guns at home. Take the position, “I know this was an oversight/accident/misunderstanding, but …” Be prepared to tell the client exactly what compensation you require, and explain how you arrived at your figure. Most of the time, whether the violation was intentional or accidental, the client is willing to comply.

If you meet with an uncooperative response, the next step would be a little chat with your lawyer, which we will deal with in detail in chapter eighteen.

Not all fee violations are as obvious as copyright infringement. Sometimes clients carry away the photographer's profits a few crumbs at a time, like ants at a picnic. One big way they do this is by squeezing extra shots into a job after you've already arrived at a price. It used to happen to me all the time when I shot commercial jobs. I was hired to shoot twenty-five cutout shots of kids and the client shows up toting thirty-five assorted play tables, sandboxes and art easels, and says, “Gee, we forgot to have the product photographer shoot these, can you just sneak these in between the kids shots?” The correct answer to this question is, “Sure, we can work those into the schedule! The shoot will go an extra four hours, so that'll run another half day.” But they're standing there with the furniture they've lugged all the way up the freight elevator, smiling at me hopefully and I know they want me to “just throw it in” and they know I know, so it's a standoff.

Another little profit crumb gets carried away when a job that was supposed to run regionally suddenly turns out to be national. Or a job that you shot for one local store gets picked up by one of the store's vendors and used all over the country. Often these infringements are carried out in markets that the photographer never sees, and you never find out. I don't know of any way to keep tabs on all the markets in the world. If you do find out, you should first approach the offender and request remuneration. In the unlikely event that the request is denied, the next step is legal action. If this is the case, you should consult an intellectual property law attorney. Many people give up at this point, intimidated by the financial and emotional cost of a legal action. But if you follow through, you'll be doing a great service to your fellows in the industry.

RAISING PRICES

Many businesses have formulas they use to figure out when and how much to increase prices. I had one vendor that raised prices 10 percent uniformly, across the board, every year. It had nothing to do with actual inflation, their COGS or the economic environment — they just did their 10 percent increase each year, come hell or high water.

In some years inflation is nominal and the consumer index drops, so many businesses hold off on price increases temporarily. On the other hand, the cost of medical insurance, worker's comp and rent in some areas have skyrocketed. So what's a photographer to do? When and how much should she raise her prices?

A slow, steady increase is best. I made the mistake of going six years without a price increase. I'd like to tell you it was part of a brilliant marketing scheme, but the fact is, I was simply not paying attention. My COGS and fixed overhead were going up every year, but my business was growing every year, too, so my income was increasing even though my margins were dropping. Then suddenly, I woke up and smelled the coffee. My trusty accountant told me, “You know Vik, you should be hanging on to more of this money you're bringing in.” So I checked around my market to see what my competitors were charging and raised my prices about 20 percent overall.

That seemed like a great solution until a long-standing client came in and threw a fit. She felt betrayed. “How could you do this? I've been coming here forever!” she said.

Jim Zuckerman sells editorial travel images such as this one through stock agencies.

At first I just wanted her to leave my studio and never come back. But after some contemplation I realized she was actually doing me a favor. I realized that if she felt this way, there were probably other clients feeling this way, too, only they weren't telling me about it. They were just ticked off and maybe they were even taking their business elsewhere. My solution was to honor the old prices for old clients for one year. That way I could have my much-needed price increase, but my old clients felt pampered and appreciated. And now I keep my eye on my margins, so I make small increases when necessary instead of big ones when the situation is about to turn ugly.

I wouldn't recommend raising prices just because another year has gone by, but don't wait until you're just doing damage control.

The bottom line on pricing your services is this: Always do an honest job for honest pay. Learn what your industry standards are and position yourself within those standards according to your ability and experience level, taking into consideration your costs and the realities of your market. Don't let your emotions get in the way of collecting fair fees.

Ibarionex Perello says it very well: “You need to charge enough for your work to get your clients to give over their complete and total trust in you. Not only that, but the less you charge, the harder you'll work, because your clients will respect you less. You may think you should charge less than market value because of what you don't know. But you should charge based on what you do know.”

Don't give away your copyrights. Intellectual property is still property — you wouldn't give away your house after all! And keep your price increases slow and steady. Do all this, and your clients will respect you, and you'll respect yourself.