CHAPTER 2:

YOU ARE HERE

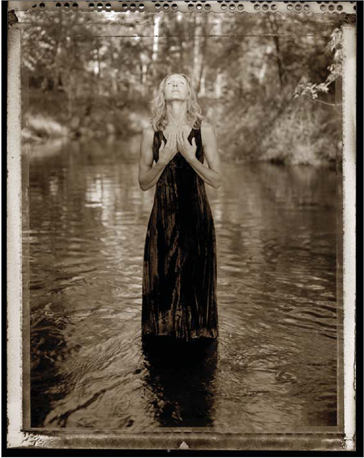

A portrait of California poet Lisa Teasley by Ibarionex Perello.

Since you're reading this book you are in one of these places: A) You are a student looking for a direction in education. B) You are a career person in search of a career change. C) You are an established photographer looking for inspiration to maintain, grow or diversify your business. D) You are reentering the job market or entering it for the first time.

People come to the photography industry from disparate places in their lives. One way to learn whether this business is for you, or to validate your choice if you're already “in,” is to look at the way others have come into the field and created their photographic careers. Here are the stories of a few successful photographers and their different approaches to their careers. I interviewed several of the photographers for the last edition of this book and then touched base with them again to see how their business has changed. Some of the photographers I interviewed for the first time.

IBARIONEX PERELLO: A STORYTELLER

After many years working in the field of photography — from working in tech support for Nikon to writing and shooting for magazines to producing a photography podcast (The Candid Frame) — Ibarionex, with his partners, has started his own business.

How old were you when you decided to be a photographer?

I knew I loved photography when I was eight years old and I got my first plastic camera — I was hooked! But I didn't know until much later that it could be a career choice. I didn't know any photographers who made a living at it. I only knew of the masters, whose work I saw in books. And they seemed light-years away. So I started street shooting and working in the darkroom at The Boy's Club in Hollywood. Photography became a normal part of everything I did. But it wasn't until I joined the newspaper in college that I realized I might be able to make a living at it.

In the last year, you and your partners founded a new business, Alas Media. It would seem on the surface that this would be a less than ideal time to start a business.

There's never an ideal time! Just jump in and do it. Don't get preoccupied with, ‘money's tight.’ There's always someone making money — it may as well be you! The biggest pitfall to avoid is worrying about all the stuff you don't know. You should focus on all the things that you do know! I waited years too long to go into business for myself.

But speaking for myself, the things I don't know (and especially the things I didn't know when I first started out in photography) are really scary! The things I didn't know, in fact, made me fall on my face in front of clients more than once.

Yeah, well, get over it! The creative process is full of risks. Life is full of risks. If you focus on your strengths, you'll build on that and learn the things you don't know as you go. Your strengths are and always will be what makes clients want you.

You're a writer and a photographer. Does being good at one job help with the other?

We're all storytellers. As a writer and as a photographer, it's all about using your skills and tools to tell stories. That's what a lot of companies are trying to do — it's a means of connecting with their potential clientele, to get them excited about their products and services. That's how I pitch my services to commercial clients: Let me tell your story.

You make it sound easy.

Its not easy, but if you have the fire in your belly, you can do it.

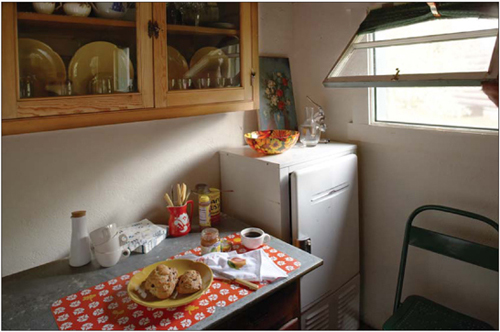

KERRY DRAGER: A RENAISSANCE MAN IN WORDS AND PICTURES

Kerry came to the business of photography with a bachelor's degree in journalism. At first photography was simply a side pursuit for him–he took a grand total of one photography class in college! Kerry started his career as a part-time copy editor for The Sacramento Bee and a freelance writer.

How did you wind up becoming a professional photographer?

One day in 1980, the last straw occurred: Yet another roll of film failed to meet my great photographic expectations. That's the day my “visual quest” began. I started reading how-to books and camera magazines; taking workshops and seminars (alas, no online instruction back then!); analyzing the work of professional photographers; and doing a lot of shooting, experimenting and reviewing my photos. Eventually my images began to accompany my newspaper and magazine articles. I began a full-time life as a freelance photographer and writer. Later, I had three books published. I also began teaching photo workshops, and in 2004 my interests in photography, teaching, writing and editing came together when I joined BetterPhoto.com full-time as both staff member and instructor.

Detail of a 1965 Chevy Impala by Kerry Drager.

How did you know you had the right stuff to succeed?

This is really an important question. For a photographer, if you are studying the marketplace, there comes a time when you say to yourself: “I could do that!” or “Hey, if he can open a studio, then so can I!” Or “My work is as good as hers, so why is she getting published, and I'm not?” Comparison and knowledge really are the key factors in the path to photographic success, and that comes with learning all you can about the industry and then seeing how your own photography measures up with the work of the pros.

Did you ever have a “lightbulb” moment when you knew you were the real deal, a real professional photographer?

I actually had several of them, though some were more important than others! My first major magazine sale was a photo/article spread. The piece was an account of my solo trip in a remote backcountry area, consisting of text and nearly a dozen photos — mostly landscapes and self-portraits showing myself on the trail, beside a campfire. Thus began my appreciation of tripods and self-timers! Bigger steps in my career occurred in the late 1980s, when two of my images appeared in the competitive Sierra Club calendars. More turning points came in 1993 with the publication of my first book, California Desert, and then with a major profile piece about my work in the April 1994 issue of Outdoor Photographer magazine.

What's with all you guys who teach photography online, in colleges, in books and workshops? Aren't you afraid you'll put yourself out of business by creating more competition for yourself?

To me, teaching is fun, inspiring and eye-opening. Plus, I find it gratifying to help aspiring pros. After all, many photographers contributed to my own photographic and professional growth, many of whom I've never met! And there was certainly the influence from many other photographers I got to know personally at key stages in my photo career, and many of them remain friends. When my skills and experience reached a certain level, teaching just seemed like a natural progression — in print, in person and, more recently, online.

Do you have any advice for an aspiring professional photographer?

Beware of the “fear factor.” Many budding professionals are afraid of being rejected, although rejection is a big part of professional photography. Some photographers whose work is turned down feel discouraged and give up. Other shooters also feel discouraged, but they quickly become energized by the rejection: They try even harder. Strive to be one of those people who views a negative (rejection) in a positive way.

KAREN MELVIN: FROM DENTAL HYGIENIST TO ARCHITECTURAL AND ADVERTISING PHOTOGRAPHER

Minneapolis advertising/architectural photographer Karen Melvin came to photography after a brief detour into dental hygiene.

“I knew I was making a wrong turn, but my mother wanted me there. She dragged me back to school. There were black heel marks all the way to Milwaukee.” She laughs. Now, fifteen years into her career, she is just finishing up a bachelor's degree in photography at the University of Minnesota.

Why finish your degree now?

I have an eleven-year-old son. I didn't want him getting a degree before his mom did. Actually, I started it many, many years ago. But I got busy and life happened. I'm very excited about the courses I'm taking — they're very germane to my career. A course I'm facilitating is called, “Where art meets commerce — finding your value in your market.” That's pertinent to anyone's career at any stage. Another is in digital imaging, which is an area where I'm light-years behind.

Backing up a bit — how did you learn to shoot?

I always photographed when I was selling on the road in my twenties. When I decided to make photography my career I took a crash course at a school of communication arts. I was lucky to have a commercial photographer as my instructor. He was a relentless technician. The other major influence was assisting the graduate school of photography.

Your husband, Phil Prowse, is an architectural photographer as well. Does that cause any problems?

What kind of problems?

Like, for instance, battling for the same clients?

Oh, no! Phil does his specialty, and I do mine. He does boy architecture, and I do girl architecture.

Please explain that!

Oh, I do residential interiors and lifestyle, and Phil does commercial buildings and exteriors, sort of …

Phallic?

Yes! Phil does phallic and I do the womb. It's nice because when I get a call for his specialty I refer them to him, and when he gets one for mine he refers them to me. Phil's learned to say, “I'm referring you to my partner,” because it sounds more professional than, “Here, talk to my wife.” I don't want to give the impression I'm sitting around the house eating bonbons. But we don't need a studio. All our shooting is on location.

A residential interior by Karen Melvin.

Has that helped keep your overhead low?

Yeah. I think I've survived in every economic market over the last fifteen years because I never had a studio. Location shooters who have studios tend to go under in a bad market or move back to their home offices.

How did your career start out?

I assisted first, my instructor from school, and others. All along I was showing my book. I marketed to architects and interior designers, but a lot of other businesses, too. Hospitals, public relations firms, anyone who used interior shots. Then along with other freelance jobs I got an internship at Skyway News that turned into a three-year stint as a professional wrestling photographer.

Another little detour?

Not quite as off the track as dental hygiene.

At any rate, you evolved into an architectural photographer, but you've honed your specialty even more, to residential interiors and lifestyle. Tell me about that.

To thrive in a tough market, I've had to refine my message, ratchet up my art to pull myself out of the fray. I do that by showing work where light is the hero. I use and create light as a theme in my work. So it's architecture, but with a message of light.

The level of specialization required in these times is extreme, but I think it works to everyone's advantage. By working deep, not broad, you get to create a career that's exactly in line with your vision. You may not get every job, but you'll get most of the jobs that are perfect for you.

If you could go back, would you change anything?

Only that I'd start to promote my work nationally earlier. It brings me more commercial clients, more advertising work. I love this field! It takes more legwork, but it has better production value and it pays better than editorial.

Any advice for the newbies reading this book?

You need to be persistent and keep reinventing yourself and your art.

Update

Now Karen says business is pretty good. “I can't complain. When the economy is down I always have to do more marketing. Lately I've been sending out e-mails with an image and a link to my website. I get a 5 percent return rate. That's really efficient.

“I also take very good care of my existing clients — good customer service.”

Karen has also joined the ranks of digital shooters since 2004. “I resisted for a long time, but now I realize that it's a great tool.”

STORMI GREENER: PHOTOJOURNALISM AND OCCUPATIONAL HAZARDS

I first interviewed Stormi Greener in 2004 for the first edition of this book. I caught up with her again for this book. Both parts of the interview are here to show how her career has changed and the photojournalism industry has changed.

“It's easier to shoot [pictures] in a war zone than to shoot weddings,” says Greener. This from a woman who has been shot at in Bosnia, stoned in Afghanistan and beaten in Israel. No, she's not kidding. Not entirely.

“You go to war, and you don't think. You just do what you have to do. You're on adrenaline, on autopilot. But you go shoot a wedding …” She shrugs.

Does every photojournalist have to go to war?

No. I chose to. You could work on a large paper and never go overseas.

Do you still go overseas?

No! At fifty-seven, I do not want to go to war. I say to myself, “Would I rather be there than here?” and the answer is no.

Did you start your career doing this type of assignment.

No, I started out in Idaho, shooting fires, bike accidents, the usual.

You had a degree?

No, these days you have to have one, but in those days you didn't. My degree wasn't in photojournalism. I got the job not from what I knew but by being a pest. I didn't have much photographic work, and what I did have wasn't very good. But I asked the publisher of the paper for the job. He said, ‘Oh, you're not a photographer, go to work in the library.’ It took me months to wear him down. Finally, he put me on for sixteen hours a week. I had assignments, and I found my own stories, too. One of my colleagues, Tom Freick, taught me so much — what a lens would do for me, how to walk into a situation and size it up immediately. I owe a lot to him.”

American soldiers handing out supplies to refugees in Afghanistan by Stormi Greener.

I assume anyone starting out now in photojournalism would have to relocate to a very, very small market.”

Yes, but it's not so bad working in Podunksville. If you're good, within a year you'll be getting plum assignments and movin' on up.

Aside from getting a degree and being a pest, what can you recommend to aspiring photojournalists?

Well, if you're on the young side, get a job on your yearbook staff and on the school newspaper. Look for a school with a good program, find a mentor — someone who will help you is a must — do internships. Internships are never a dead end; they're always valuable. You get practical experience and you get to hang around professionals.

So you'd recommend your job?

Sure. I love it.

So regrets?

Well … that's a loaded question. If I could go back and do it over again, I would do a better job of balancing work and family. I didn't realize how much my job affected my daughter until she was grown and she made a video as part of a Nation Press Photographers Association “flying course.” She talked about hearing the phone ring in the middle of the night and knowing that when she woke up her mother would be gone. She talked about wondering what would happen to her if I were killed on assignment. She basically blasted me.

How did you feel about her discussing this in a public forum?

It hurt, but it was important — hopefully it will help others learn not to let the business eat them up. That's the most important piece of information I have to share.

Update

Stormi left the Minneapolis StarTribune in 2007. But she hasn't retired! She stays busy shooting weddings, shooting and managing the images for Dakota County in Minnesota and doing various other projects.

Do you miss photojournalism?

Not at all! I thought I would, but the industry is in such an upheaval! The Internet has really changed everything — the Web has become the new focus. Now to shoot for a paper you have to shoot video, too. I have no interest in shooting video.

And you're shooting weddings! I thought the wedding industry was overcrowded and undervalued now that everyone's Uncle Louie has a DSLR.

If it is, that's news to me! Yes, everyone at weddings has their little point and shoot and they hold it up over their heads to get a shot, so that makes my job harder — being way in the back and trying to get a shot of the couple without a sea of arms in the air. But I only shoot a fixed number of weddings a year, at a flat rate. Those are 14-hour days, you know! It's very physically demanding. So by limiting the number of weddings I do and having a flat rate, I know how much I'll make and I won't overdo it!

Isn't it hard to turn business away?

No. Years ago, I wouldn't turn down anything–I would take everything, every assignment. But now I control my time. I'm my own boss.

PATRICK FOX: A TEXTBOOK EXAMPLE OF COMMERCIAL PHOTOGRAPHY

I interviewed Patrick Fox in 2004 and reconnected with him to see how his business is growing despite economic downturn. Patrick Fox is a top-billed commercial photographer in Minneapolis: He runs a 6,000+ square-foot studio in the trendy warehouse district, and he shoots almost every day — a phenomenon almost unheard of in this medium-sized market. His seventeen-year career has weathered economic upheavals, dramatic fluctuations in the local market and all the usual stages that a business goes through when it ages, expands and adapts to changes in technology and market demands.

Patrick forged his career pretty much by the book: He attended Brooks Institute of Photography and holds an MBA in photography. After college, he assisted a food photographer for one year, worked in-house for five years shooting fashion and product for a department store and opened Fox Studio, which specializes in location fashion and product shooting, in 1987.

What got you interested in photography to begin with? Was it to meet girls?

(Laughs.) Yes, most guys in this business go through a stage I call the “I gotta shoot babes” stage.

But that stage doesn't last?

It can't last. This is way too tough a business to be in just to get dates.

A test shot by Patrick Fox for his portfolio.

But you do get to shoot babes?

Yes. You do get to shoot babes. But I'll tell you right now, anyone thinking of becoming a commercial photographer should take a good, hard look at themselves and ask: “Do I have vision? Do I have a good personality? Am I bright creatively and technically? Do I have the abilities necessary to run a professional business? Am I lucky?” It takes luck, but of course as you know, we make our own luck.

So maybe by luck you mean persistence? Passion? One of those P words?

Yes! Persistence.

What about talent?

Sure, you have to have talent.

How do you know if you have talent?

You have to show your stuff. Not to your mom or your friends — to people who know their business and will level with you. I personally know of several art buyers — people at the top of their fields — who will see your book if you call and ask, and then call and ask again a few more times … if you're persistent.

So wait, let's back up. Say I want to be a commercial photographer. I'm talented. I'm creative. I'm technical. I'm a people person. I'm business savvy. I'm lucky. Where do I start?

Definitely school, or some extremely intensive training.

Photography school?

Sure, yes. But a liberal arts degree is great. That's what I look for — a well-rounded liberal arts grad, because you can teach someone how to shoot, but you can't teach them how to think.

So school, then the big time?

No! School, and you get a lot of feedback on your work. Then you make a portfolio or book. Then you get a job. When I first started, you only had to assist for about a year. Now you have to assist for five years. A lot of people think they're going to get a great job just out of school. But that doesn't happen. School is just the starting point. After that, the learning begins.

What kinds of images do I put in my book?

You show your ten best images, no matter what the subject. As you get new ones, rotate out the old ones.

But I want to be a successful photographer. Translation: I want to make the big bucks. So aren't there certain specialties, or types of images, that are more salable? And shouldn't I specialize in those hot areas?

No. Start general, then specialize as your career matures. You want to get to higher and higher levels of competition. When you first start out, you'll be competing against fifty other guys for the same job.

Then, after a while, it'll be you and twenty-five other guys. Then you and maybe five guys. Then ultimately, it might come down to just you and one other guy — your nemesis. Eventually, you will have to become highly, highly specialized. It's become almost ridiculous. To give you an example, I was showing my book a while ago. The art buyer said, “This book is very ‘springy.’ Can you shoot Christmasy? That's how extreme it's gotten.

You said you were showing your book. Do you work with a rep?

Yes, but I only started recently. And it's not a conventional relationship. Normally, reps are paid a percentage of the jobs they sell. My rep is paid by the showing.

That's a pretty big change from the last time I worked in the commercial industry seven years ago.

There have been a lot of big changes since then. Like art buyers. It used to be the art director who chose the photographer. But now the art buyer is the gatekeeper — the art buyer's entire job is to hire artists and photographers. It's a better system. The art buyers know who's best for a job better than the art directors used to, because it's all they do. So far this trend is largely in the bigger agencies, but you see it in some smaller ones, too.

Speaking of changes — it seems to me that the eighties and nineties were a golden era for fashion photography. Shooters charged high fees and got plenty of work. Then it all dried up. Any insight?

I can only speak for this market. But, yes, we had a couple of huge clients in Minneapolis who made this a bigger market than the size of this city would dictate. But we had a very small talent pool (talent being another word for models) and the big clients took their shooting to other cities. Then there was a trickle-down effect, and other clients left, too. And then of course, what good talent there was moved to other markets.

Is that why you shoot product as well as fashion?

No. That was a lifestyle decision. To shoot all fashion I would have had to be willing to travel a lot. I'll travel some, but I like being here. I have a cabin up north. And I enjoy product work.

So what's the secret to your success?

There is no magic bullet.

But darn it, Patrick, as the author of this book I'm duty bound to provide a magic bullet: a recipe.

I was the president of American Society of Media Photographers for two years. Every once in a while I'd answer the phone and it would be a guy wanting to know the recipe. He'd want us to tell him how it's done. There is no recipe! What works for you is what works for you. I do things one way today because it's the right thing to do — today. Maybe tomorrow I'll do things differently.

That said, it certainly doesn't hurt to find out how other people do things and to get other people's opinions. But don't mimic them. Take what you learn and tweak it — make it your own. A person who only knows how to do what someone else does will not succeed. It's the person with vision — the person who learns how to cook and then writes his own recipes — who will succeed.

I notice that in bad economies there are photographers who shoot for dirt cheap fees just to keep the business rolling in. How do you compete with that?

I don't.

So a bad economy doesn't impact your business at all?

I can't say that. In bad times I'm not turning away jobs like I do in good times. There have been times when I've turned away 33 percent of the jobs I get called for. But in bad times I'm still shooting almost every day. So I can't complain.

In a nutshell, what really important advice would you like to leave us with?

Read. Anything and everything. Not just about photography. Read about stuff you don't like or have no interest in. For instance, my politics are liberal but I read The Wall Street Journal every day. Have an understanding of how the world works and how life and events all fit together. Then you'll be prepared for anything.

Update

Today we find Patrick as busy as ever. Unbelievably, 2007 was his best year ever by a large margin, and 2008 stacked up to be even better.

With the economy in a shambles, how do you explain that?

Partly it's because we're running really lean. I still use the same cameras from three and four years ago, and light stands, strobes and other equipment I've bought over the last twenty years.

I thought we were always supposed to buy the latest and greatest equipment?

No, we don't. If you're trying to compete based on your equipment, you won't get very far.

What's your advice for aspiring photographers?

Well, the realities of the economy are different from when we started out. It's a challenging career, and it's hard to break in. But what isn't hard right now? Is there any worthwhile career that isn't hard to break into?

LEE STANFORD: A LOST SOUL BECOMES A COMMERCIAL AND FASHION PHOTOGRAPHER

What brought you to a career in photography?

I'd had four years of college, and I still didn't know what I wanted to do. Marine biology seemed neat. I had an art minor. Then journalism seemed exciting for a while. I finally decided I was wasting my dad's money and stopped going.

So when did you go pro?

That's open for debate. Maybe in '85. I shared a studio with two designers and I shot model and actor head shots and comps. I started getting small jobs for local hair salons, and the business just grew by word of mouth. My first official commercial job was shooting girls in bikinis for a beer company. How cool is that?”

In 1986 Lee committed himself to larger fixed overhead by signing a lease for his very own 2,000-square-foot studio in the trendy Minneapolis warehouse district. He has never looked back.

Has every year been a good one, financially speaking?

I've had growth every year for pushing twenty years even in bad economic times. Can't complain about that.

That's steady growth for eighteen years with no rep and very little self-promotion. In fact, Stanford's experience goes against much of the information in this book. He must be the exception to the rule.

Since you yourself admit you're not very good at marketing, why didn't you get a photographer's rep to do it for you?

I tried to get a rep. No one wanted me. I guess my look is on the artsy side and most reps I talked to felt that would limit me too much. I hardly ever show my book. I hate that part. I know I should do it more, and I should schmooze more, but I don't. I probably lose some business because of that.

Have you done any formal study on the fields of photographic technique or business?

No. If I had to do it over again, I'd take a business class. Just for things like filing for tax exemption numbers and things like that. I had to teach myself business right along with the photography.

Do you regret skipping photography school or assistant work?

I learn faster when I teach myself. Essentially, I learned by cutting photos out of magazines and re-creating them myself. Some people come out of photo school with very rigid ideas about how things should be done. They're afraid to break rules. But school's not bad for everyone. As far as tech school versus art school goes, I know a guy who went to Brooks and a guy who went to a tech school and they both do really great work.

Would Lee recommend this career?

Yeah! I can't think of anything better! You get to make up your own job. You have flexibility — you can work nights or weekends if you want.

Update

Lee's studio is in a new, larger space, and he's weathering the economic downturn. In fact, he's raised his basic day rate (placing himself at the low end of the high-priced shooters, whereas before he was at the high end of the mid-priced shooters.)

That would seem to go against common wisdom — raising your prices when times are tough.

It's still about perceived value. I will knock it down a little for some clients, but then I have to charge for small stuff like, two hours of prelighting, so it all comes out about the same.

And you're shooting digital now. Has this changed anything for you?

Not really. Just turn-around time. We don't have the markup on film anymore, but I have to charge for file conversions, post processing, archiving — so again, it's kind of a wash.

Has digital capture made you a lazy photographer? Just knowing that if something isn't perfect, you can fix it in Photoshop?

No! I still want to get it perfect in the camera! But I can't believe how often I have clients say, “Don't worry about that! We'll just fix it in post.”

When we last talked, you admitted to being guilty of not promoting yourself enough. Has the Web changed all that?

My website is my only promotional tool!

“Only” only?

Well, I still have my book and I show it maybe once every nine months. Someone will go to my website and then call and ask to see my book. That's good, because they'll tell me what they're interested in, like location lifestyle — and then I can tailor the book for them.

What's the main difference between Lee Stanford, newbie photographer, and Lee Stanford, seasoned photographer?

I'm smarter now, business-wise — I know how to make bids better because I know what it takes to get the job done, so I know what to charge to be sure I get compensated fairly.

Fashion would seem to be a very youth-oriented business. Does it hurt you, not being “young”?

I can't be the next new thing anymore — but I can produce very high-quality images efficiently and consistently.

When we last talked in 2004, you said you would recommend this business to aspiring photographers. Is that still the case?

Yes. But in this environment, I'd recommend a shorter learning curve than I had. 1) learn to take pictures, 2) learn to run a business; 3) learn how to get paid to run a business. You have to learn all of it all at once.

DAVID SHERMAN: NBA TIMBERWOLVES TEAM PHOTOGRAPHER

David Sherman came to photography relatively late in life, after working in the real world for eleven years. He holds two degrees in agricultural economics — not exactly an area that hints at his ultimate career choice.

What did you do before you began your photography career?

My first job out of college I worked in a bank marketing agriculture products. I was always interested in photography — I took one undergrad elective course. But I just didn't see it as a way to earn a living.

Often in creative work, we get to break the rules. The lens flare in this fashion image is intentional, and serves to heighten the edgy mood by Lee Stanford.

What changed that?

In 1991, I realized my work was just not making me happy.

Being dissatisfied with your job is one thing, and making the leap to becoming a self-employed photographer is another. How did you work up the nerve to take such an enormous risk as changing careers after 11 years?

I kept my day job! For more than four years. I started out doing Bar and Bat Mitzvahs and weddings on the weekends. After that I was ready to make the move to full-time. So I made a business plan in preparation for applying for a bank loan. But before I applied for the loan, I got lucky. I had a very generous cousin who believed I could make a go of it, and he financed me completely.

Did your strong business background help you build your successful photography business?

Yes. No. Yes. I mean, it helped prepare me for negotiating with clients and freelancers, anticipate personnel issues and understand cash flow.

Any regrets about shelving that unfinished business plan?

No. You'll be told that you must have a business plan, but that's bull. At the end of the day I'm still a photographer. I get paid when I work, and I don't when I don't. You can't really make a business plan for that.

If not your business background, then what factors did help contribute to your ultimate success?

I was very lucky, the NBA [National Basketball Association] did a wonderful thing for me, they paid me to learn on the job. So these league shooters led me around from game to game and taught me everything until I was ready to shoot: timing, angles, special equipment … everything. [For] every aspect they shared their experience and knowledge with me. They were great. And another thing that helped me get started is my easygoing attitude. A lot of my work I get because I'm easy to work with. I don't have much of an ego. For instance the Timberwolves gig — I got that job over other more experienced photographers who were willing to relocate for it. The reason I got that was because I'd done a little freelance shooting for the organization (not games, but crowd shots), and they liked me so they really went to bat for me — pardon the sports pun! I was willing to hang out at every game, assist for nothing … so when the league ended their contract with their previous shooter, I was there, and I had friends in the organization.

What about desire as a motivator?

I wanted to succeed. I had to succeed, because I wasn't going to go back to the kind of career that I left.

Any regrets?

No, no regrets. But if I could do something different I'd have somebody — not an agent, but a partner, someone as committed to the business as I am, to field calls, make bids, produce jobs and show the book.

Would you recommend this career?

It depends on the economy. In bad times you find out which clients are loyal. A lot of them will start shopping price when times are bad, and go with the low-ball bid even if the quality isn't there. So that would be hard. But if the economy is good, go for it.

Update

David finds the biggest change in his business is his media–he now shoots exclusively digital capture. “It's final,” he says. “I just sold all my film equipment. And all my clients are fine with it. Even the ones who initially dragged their feet.”

Do you find digital workflow complicates your business, what with file formats, storage, backup, organization and all that?

My business has been simplified because of digital. It's now as straightforward as capture, deliver, archive.

You make it sound like capture, deliver, archive is simple — but I'm just getting the hang of it after two years.

I have two raid servers (redundant backup systems) and a bucketful of hard drives. That's way simpler and takes up less space The Minnesota Timverwolves by David Sherman. than negatives and slides. I don't have to touch the images as many times.

What about altering photos in Photoshop? Do you get bogged down with editing?

Most of my business is commercial now — I turn down most retail. So my commercial clients do the post themselves. But for retail, it's like this: When there was film, there were labs. The labs did the retouching and printing. Now there's digital, and there are labs. That's what labs are for, retouching and printing.

Do you think the proliferation of digital photography has created more good photographers?

No. It has created the myth that anyone can be a good photographer if they have a good camera. Nikon has proliferated this myth with their ad that says, ‘with this camera, anybody can take great pictures.’ I would never buy a Nikon, just because of that one offensive ad.

The Minnesota Timverwolves by David Sherman.

You mentioned you're turning down most retail work now. Do you ever have doubts about having made this move in your career?

Yes, but at age fifty, it's different from age thirty-five or even forty-five! My time is more important to me and being happy at work is more important to me. Yes, I still have to make a living, but I can do it on my own terms now.

What about your rates? Have you lowered them to stay competitive in this bad economy?

No. I actually raised my rates within the last two years.

Has that hurt or helped your bottom line?

It's definitely helped! I've never wanted to be high-end or lowend. I've tried to price myself to be favorably compared with other premium photographers in my market.

What's your advice for aspiring professional photographers?

If you want to make a living, don't give your work away. Charge a reasonable rate. Look, we all started somewhere, but not by doing free portraits or $300 weddings. When you do that, when all is said and done you're working for $2 an hour. There's no “up” from there. People will know you're a $2 an hour photographer.

PETER AARON: FILMMAKER TURNED ARCHITECTURAL PHOTOGRAPHER

New York architectural photographer Peter Aaron holds an MFA from the NYU Institute of Film and Television. He regularly shoots for such national publications as Architectural Digest, Architectural Record and Interior Design Magazine. Most recently he shot a two-part piece for Architectural Digest on the Andrew Wyeth family compound.

“The magazine has never done a two-parter with anyone before, and of course it was fun to meet and spend time with the Wyeths,” says Peter.

You had planned to become a cinematographer. How did you wind up an architectural photographer?

I tried filmmaking for a while, but I just couldn't seem to find the right group of people [to become involved with]. Photography was always a hobby, so I thought maybe that would be a good way to make a living. I went to magazines all over Manhattan and showed my portfolio. And I got a few bites.

What kind of shots were in your book?

Everything. It was quite general. I was told that my interiors and exteriors were my strongest material, so that was how I chose architectural photography.

And so right away you started getting assignments?

Pretty much. Youth was on my side. I was maybe twenty-eight or twenty-nine. Magazines are youth-oriented businesses. The editors, the writers tend to be young. Young photographers should not be afraid to go to magazines and show their books. They are likely to get a friendlier reception than they might imagine. You should realize that the magazine isn't doing you a favor by seeing you — you're doing them a favor. They need photographers.

I assume that it's not enough just to be young.

Of course, it helps to be good.

And how did those early assignments go?

I did well on my first jobs, but I felt totally out of my depth. So I approached the most important architectural photographer of our time: Ezra Stoller. I was lucky — he allowed me to assist him, and he became my mentor. So for two years I went with him all over the world and learned a ton about composition and doing business.

And after those two years it was back to assignments?

Well, yes. At that time Ezra's daughter, Erica, decided this would be a nice milieu for her, and she joined Esto and became my rep.

Esto is an agency that represents architectural photographers?

Yes. At the time it was only intended for Ezra, but when Erica came on other photographers were brought in. I still had to market myself, because as yet I had no reputation. So Erica got some of my clients and I got some — at the beginning it was about fifty-fifty.

What made you different? What was it that made you stand out from the others calling on those same magazines?

Historically architectural photographers shot with “soft light.”They used only strobes. Coming from film school, I realized that you could light a room the same way you could light a set. I used tungsten to create expressive lighting. Side lighting and back lighting, lighting that's coming from where it should be coming from. I used pools of light instead of blankets. I guess you would call it low-key because there are shadows and shapes and depth. Now it's the norm, but at the time it was innovative. My work looked like I had just taken a snapshot — it looked natural. But it took a lot of work to get those natural shots.

So when you started out, you had youth on your side, and you were innovative. But you've been shooting for twenty-eight years. What's on your side now? Aren't there some advantages to being old and experienced?

Certainly. There was a time when I kowtowed to my clients and listened to their opinions on how to take a shot. But now my clients ask me my opinion. Of course it's harder to approach some of the magazines as an older photographer. They want the next new look.

What would the new look be?

It could be anything.

Cross-processing?

Yes, it could be that. It could be lighting with a handheld diesel-fueled flashlight. It's often something quirky. Usually it fizzles out quickly.

You have no desire to light with a flashlight?

None.

Well, obviously you don't have to. I see your published work all the time — frequently in Architectural Digest. That's a wonderful publication.

Yes, and I give them the copyrights! I'm actually not proud of that aspect of working with Architectural Digest. But the work is challenging and the published material is very well done, highly visible and excellent for my portfolio.

Are you shooting digital?

No. I'm not shooting digital at all. The technology is not wideangle friendly. They do make digital backs for 4″ × 5″ (10cm × 13cm) cameras, but the minute you slap a wide-angle lens on there, you get fall off and color shifts, and other technical issues. So I'm shooting film and then making scans before the client sees the take. There are improvements that can be made — lots of improvements. I can take out exit signs and power lines and anything else that might distract from the building.

This ease with which images can now be manipulated thanks to digital technology — do you see this as a good or a bad development?

I think it's a real boon if you treat it well. The pictures look better — much better. But one shouldn't blur the truth. I don't make changes in a photo to portray anything that doesn't exist in the built world. That would be dishonest if, say, the photo were being entered in an award competition.

Aside from the ethical issues, isn't there another issue? Does the ease of correcting images digitally allow a bad or a mediocre photographer to make good images?

Interesting. I'm not worried about that, because you have to be able to light well. Even the very best Photoshop artist needs a well-lit image to start with, or there really isn't much he can do with it.

So you would recommend this business?

Yes, to a qualified person, certainly.

Update

Catching up with Peter, I found that he is about to receive a collaborative achievement award from the AIA (American Institute of Architects.) He is now shooting exclusively with digital capture.

What is the best thing about digital photography?

Interior of Bard College Science Museum by Peter Aaron.

Everything! Now I can put crowds of people in my pictures, change the view out a window, create perfect color balance even with mixed light sources — I can make pictures that in the past would not have been possible due to the high cost of retouching [analog images.]

So you're drunk with power?

Yes, I am. I used to make pictures with one layer, but now I use many elements from different pictures to create a final result. I have used up to twenty elements to make one picture.

Doesn't this add a lot of post-production time to your work?

Not really. I don't consider what I do “Photoshop.” I label and prepare the images and then turn them over to my photo editor.

Has the downturn in the economy affected your business?

Not yet. I'm fortunate in that I have a captive audience. Architects always need good images of their work in order to sell themselves.

What about less established architectural photographers?

Actually, gifted ones can do quite well. For instance, Tim Griffith is an architectural photographer who does great work. He does about half on spec — he shoots iconic buildings at his own expense and then often is able to sell them to the architects. He's very ambitious. It's nice that if you stick your neck out, good things can happen. It doesn't always get chopped off.

JIM MIOTKE: A PARALYZED NOVELIST BECOMES A STOCK, PORTRAITURE, AND EVENT PHOTOGRAPHER

Jim Miotke graduated with an English degree from the University of California at Berkeley.

“I had my heart set on becoming a novelist, but I was completely immobilized by fear,” says Jim, who can chuckle about it now. “I'd always liked photography. I took a few high school classes and one workshop. I picked up some knowledge working at a camera store and at a photo lab, but mostly I'm self-taught.”

I assume nonfiction isn't as scary for you to write as fiction, especially since your how-to book, The Absolute Beginner's Guide to Taking Great Photos (Random House), is doing very well.

Yes, nonfiction, for some reason, comes easily to me. It was a natural thing to combine writing and photography. And I guess the teaching is a natural offshoot of that.

Yes, the teaching. Tell me about your website.

In 1996, I founded BetterPhoto.com. Then, in 2001, we start-ed offering photography classes. All our teachers are published authors and are highly respected in their fields. I teach a beginner's class, of course. I look at my teaching work at BetterPhoto.com as a healing mission — to help people overcome their fear of equipment, of approaching a stranger, of business in general.

Through your website and your teaching you meet a lot of people who want to become professional photographers. What advice do you give them?

You need a great deal of humility — especially in any type of portraiture. It's really a service industry, more so than commercial, fine art or nature. You need to be able to be comfortable with uncertainty.

Don't quit you day job! Know that you have to do a lot of other stuff besides shoot pictures. People are often not receptive to the idea that you don't just start out at the top of your field. Is there any field in which you can start out at the top? But all that said, it really is true that if you do what you love, the money will follow.

Update

Jim has published two more books since 2004, and produced two DVDs. BetterPhoto.com has continued to grow at a breakneck pace and has added website hosting and templates to the services offered to its members.

Why websites?

Whether you're a part-time or a full-time pro, a Web presence is absolutely essential. This has been true for many years, but never more so than now. The Internet is such a powerful communication tool for prospective clients and art buyers, every photographer should have one.

Jim Miotke graduated from Berkeley with an English degree — but in the field of photography, he is essentially self-taught.

Has your advice for aspiring professional photographers changed since 2004?

No, it hasn't changed, but I'd like to add to it. In a saturated market such as this, the very first thing any talented amateur should do before attempting to go pro is to get a few good books on marketing (like this one). Focus on marketing and promotion right along with photographic artistry and technique.

Also, it's extremely important to open yourself up to getting help from others. Most of us photographers tend to see ourselves as somewhat shy people. If you can overcome any shyness, make friends with partners, contractors and other photographers and business owners, you will see your business grow at a much faster rate. And you'll have more fun … because life is more enjoyable when you share the ups and downs with friends.

LEO KIM: A LABOR OF LUST, COMMERCIAL AND LANDSCAPE PHOTOGRAPHY

In 2004, I talked with Leo about his work in the disparate specialty areas of fine art, landscape and commercial photography. I caught up with Leo again recently, and I've learned that even a brain tumor has not kept him from his first love — making pictures.

Leo Kim was raised in Shanghai and Hong Kong, lived for a while in Austria and was educated in America's heartland. He always loved photography from the time he was small — using his hand, he indicates a height of about knee level above the floor. But he graduated college with a degree in architecture and design. The photography had been temporarily abandoned.

“After I graduated, I started thinking, ‘Just why was it that I wanted to go into architecture, anyway?’ I kept thinking about the beautiful black-and-white photographs of [architectural photographer] Ezra Stoller, and the wonderful images of Austrian commercial photographer Ernst Haas — he likes to play with color — and they really inspired me to find my own visual style.”

Like many of the other photographers featured in this chapter, Leo is totally self-taught.

Why didn't you go into architectural photography? With your background, it would seem to be a logical progression.

A lot of people ask me that. I don't have one answer. I love forms, shapes, textures. I love O-rings, I find them very exciting to look at. My style springs from arranging shapes to make a simple but beautiful picture. You can't really rearrange buildings! One of my clients once brought me garbage bags full of rubber parts. They were not labeled, not boxed — nothing. They wanted one 4″ × 8″ (10cm × 20cm) picture for a trade show. They told me I could do whatever I wanted to. So I made eight 2″ × 2″ (5cm × 5cm) images instead. Combining the shapes that way was much better than just one big picture. I shot them on black Plexiglas. The reflection on black is so deep!

Was the client happy, even though you changed the assignment?

Yes, they loved it. They hired me many more times to shoot their annual reports.

Do all your clients give you this kind of creative license?

Most. In my whole career I have had less than a handful of boring jobs. I believe you have to give the clients what they want but not in the same old way. It's our job to educate them, to say, “Let's do this job in world-class style!” Not with gadgets and contrived lighting, but we keep it simple. We do it with the visual style.

How do you get these amenable clients?

I have always believed in promoting myself. You have to be business first, before you are a photographer. I market my work.

Do you enjoy the business parts of being a photographer?

Oh, yes. It is a challenge. I feel I am still lagging behind at controlling my business. You have to control the business, or it controls you. One thing that has really helped me grow as a businessperson is publishing my book, North Dakota: Prairie Landscape (available through www.leokim.com). It has forced me to take new risks, to market and raise money, to keep meticulous records — all things I was doing before, but I had to take it to a higher level.

It sounds like a real labor of love.

No. It was a labor of lust! I turned down some nice jobs when I was working on the book, because when my intuition told me to go up there (to North Dakota) and shoot, I went. You can't be in two places at once. Sometimes to be in one place at once is hard!

Have you even taken any business courses?

I was just getting to that. No, but I wish I had. Of course, it's all just theory until you practice it. You take classes, or you don't. You learn it one way or another.

Do you recommend this business to others?

Yes. I love my life. I love this business. Sometimes I am out shooting and the sky opens up and the light breaks through and it takes my breath away, and I say, “This is for me? I can't believe it!”

A North Dakota Landscape by Leo Kim.

Now Leo still making amazing images both marco and landscape. Due to illness, Leo has been nearly homebound in his Frogtown coop in St. Paul, Minnesota. But even with his wings clipped, Leo finds amazing things to photograph. Lately, his focus has been on vegetables and autumn leaves.

“Not the typical autumn shots. I don't find my leaves on a beautiful mountainside — I find them in the gutter! On the street! I am looking for colors and shapes — very small pictures.”

While Leo is still working in commercial photography, he has had several very well-received shows of his North Dakota landscapes in Germany. And he sells his images during the St. Paul Frogtown Art Crawl. Typically he sells out in the first few hours of the first evening of the crawl.

In the last four years, Leo has survived a host of medical difficulties, including a brain tumor that was diagnosed in 2005. “I'm very lucky to be alive,” he says. “I live for my friends and for my next push of the shutter.”

DOUG BEASLEY: A FINE ART AND COMMERCIAL PHOTOGRAPHER, NOT A STARVING ARTIST

In 2004, I talked to Doug Beasley about his unusual market niche — Doug is a fine art photographer who sells to a commercial market. A lot of shooters — myself included — would love to have his job.

How did you pull off being able to shoot what you want (fine art) but market it commercially and make a living? I thought you had to sell out to make it in a commercial market!

I tried to sell out, but it didn't work! When I try to shoot how I think someone else wants, my work is not as strong as when I shoot from the heart.

You enjoy an extremely high level of creative freedom.

Yes. In this business when you're just starting out, you have all the creative freedom in the world! You're shooting to build your book. You're shooting what you want, because you are your client. You're shooting models' cards and actors' head shots. You have no prestige, but you're free. Then you get some commercial clients, and you lose a little. For a while you lose creative freedom as you become more successful. Then once you reach the high end, the creativity comes back. Because at that level, people are hiring you for your vision and not because you're a technician.

How did you break into the business?

I assisted for three or four years at some very high-end studios, and I learned a lot. I was very lucky.

Do you recommend assisting to someone trying to break into the market?

Yes, or an apprenticeship. Choose one person whose work you admire and learn how to do everything from them — how to shoot, yes, but also how to get and keep clients, how to show your work, how to run a business.

Speaking of running a business, does running yours get in the way of your art?

Not really. I'm looking for ways to get out of the office more, do paperwork less. But I really have no complaints. It's ironic, though, that part of the reason I wanted to become a photographer is because I didn't want to be a businessman. But that's exactly what I am.

Did you take any business courses, or have any other formal business training?

No. I learned the business by making every mistake there is — usually several times.

Do you recommend this learning method to others?

No! I don't recommend trial and error — but then again, things you learn this way are things you never forget.

You teach extensively through the University of Minnesota and through your school, Vision Quest. You must see a lot of raw talent, and a few clinkers. Can you predict who will be successful, who will make it in the business and who will drop out or fail?

Sometimes. Some just have it, but some can learn it. You can develop a visual language if you have passion and persistence, and you feed your passion.

How do you keep your passion burning?

You immerse yourself in your art. You surround yourself in it. You go into the darkroom and work. You shoot. You talk to other artists.

Has your passion ever ebbed?

Sure. In the mid-1990s I was disillusioned about the business. I was almost bitter. But I threw myself back into making images I love, and I found fulfillment again.

Can you describe what that entailed?

I simplified my method of shooting. I'm down to bare bones. When I go in the field I bring only my Hasselblad and an 80mm lens. Maybe a 120mm also — I do like shallow depth of field, but I don't want to waste energy managing equipment. I want to put my energy into engaging my subject and getting into the stream of life.

Any advice for the would-be photographer?

Recognize the beauty of this business, that you can control your own destiny; you can create your own life.

Update

Catching up with Doug, I find that he is shooting almost exclusively with digital capture for his commercial clients. But he still shoots film for his fine artwork — even in the field when he's leading workshops.

How has digital technology changed your life and your work?

It makes it harder to teach workshops the way I'd like to, with an emphasis on the process. Workshops are all about the process. But with digital capture, it can become all about the results. I encourage my students to take risks and even to fail. If they know that they'll be sharing their images, they have a tendency to do what's safe. They want to look good to the other people.

So you don't like digital capture.

I like it! It gives you immense control!

But you still shoot film for your fine art images.

Yes, because I like the look of film. But I like digital as well. They're both tools. It doesn't matter if you make a picture with film or digital or sitting in your cave with charcoal on the end of a stick. Good pictures are made with your heart.

So you don't look down on digital capture as an artistic medium. Do you think it has created more competition?

It has created more camera operators.

Doug Beasley explains the back story of this fine art image: “We were shooting nudes in the river and this was an afterthought. I love the unexpected juxtaposition of the velvet dress in the river. Working against expectations can be very powerful visually.”

Not more good photographers?

I think there are still the same number of good photographers. It's crowded at the bottom. There's always room at the top.

What do you have to say to someone who is considering this profession?

It's a tough business. Don't get in because you want to make money. Do it because you have to express yourself photographically.

So there you have it. A few of our photographers knew what they wanted to do with their lives from the time they were children, but the rest came into the field via avenues such as marine biology, dental hygiene, banking, architecture and cinematography. They came to the industry as early as their teenage years and as late as their thirties. For some it has been their first and only career; for others it's been a second or third. Many are self-taught. Some learned through the generosity of their colleagues or mentors. Others paid their dues at art or tech schools. Not only have they come into the business in different ways, each one has created a career, a specialty, a life that is unique onto itself. All have weathered economic upheavals, and some have survived phases of disillusionment, only to re-create themselves as stronger and better artists and business-people. Are there any traits they all have in common? Or is the camera their only common ground?

Perhaps they share a combination of traits: adaptability, desire, a willingness to take the grunt work along with the glamour, and, most importantly, belief in their own ability. How would your story look in this chapter? If you have these qualities, maybe you should find out.