Dylan, even beyond his singular singing voice, was going to be difficult for lots of people. It is good to understand that this was an inevitability; he was simply a difficult guy when measured against standard norms of social or professional interaction.

“I wanted to meet the mind that created all those beautiful words,” the singer Judy Collins told the author David Hajdu when he was assembling material for Positively 4th Street, his fine group portrait of Dylan and the Baez sisters, Joan and Mimi, and of Richard Fariña (who would become Mimi’s husband) and other creatures of the Village in the early 1960s. “We set something up,” continued Collins, “and we had coffee, and when it was over, I walked away, thinking, ‘The guy’s an idiot. He can’t make a coherent sentence.’” Baez herself recalled for Hajdu the first time she ever heard Dylan sing, having previously met him: “I never thought something so powerful could come out of that little toad.”

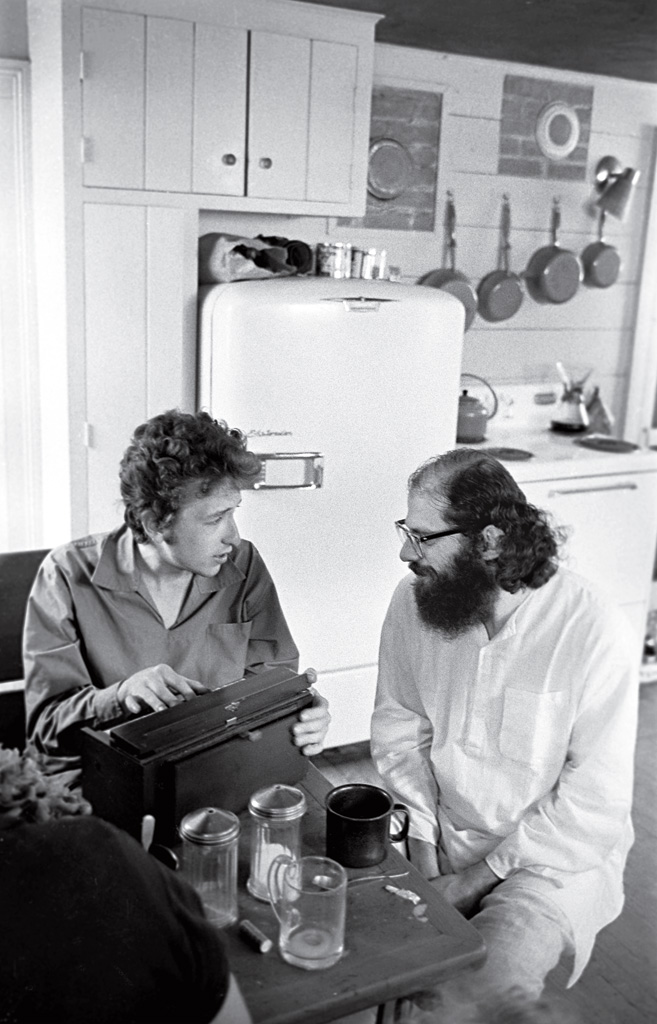

Yes, Dylan could be difficult to fathom or just plain difficult, even for those close to him. What can be seen as an inherent petulance both was and was not an act. Like his friend Allen Ginsberg, he enjoyed toying with his inquisitors: a cat pawing the mouse during any kind of Q&A. But this wasn’t a habit he developed only after he was famous and was therefore in a position of power.

Consider an episode he recounts in Chronicles: Volume One. It’s the fall of 1961, John Hammond has just signed him to a standard contract at Columbia Records and has handed him over to Billy James, the publicity chief of the label, who is “dressed Ivy League like” and whose job it is to put together the Dylan dossier for dissemination to the press. Remember: Dylan is still a kid, a nobody, and hasn’t recorded a single song.

James asks Dylan where he’s from and Dylan says Illinois. “He asked me if I ever did any other work and I told him that I had a dozen jobs, drove a bakery truck once. He wrote that down and asked me if there was anything else. I said I’d worked construction and he asked me where.

“ ‘Detroit.’

“ ‘You traveled around?’

“ ‘Yep.’

“He asked me about my family, where they were. I told him I had no idea, that they were long gone.

“ ‘What was your home life like?’

“I told him I’d been kicked out.”

It goes on like this with poor Mr. James for a while. “I hated these kind of questions,” writes Dylan, who would hate them forever. “Felt I could ignore them.”

James asks him how he got to New York City. “I rode a freight train.”

“ ‘You mean a passenger train?’

“ ‘No, a freight train.’

“ ‘You mean, like a boxcar?’

“ ‘Yeah, like a boxcar. Like a freight train.’

“ ‘Okay, a freight train.’”

Again, remember: This is Dylan at his brand new—really, his first—place of employment. This is Dylan having just been handed his big break.

Finally, James asks Dylan whom he sees himself resembling in the contemporary music scene. “I told him, nobody. That part of things was true, I really didn’t see myself like anybody. The rest of it, though, was pure hokum—hophead talk.”

Dylan really wasn’t like anyone else, and not only as pertains to his sound and songs. Call it truculence or integrity, but this fierce, immutable quirk in his personality allowed him to walk out on Ed Sullivan (Columbia Records must have been delighted about that); allowed him to treat Suze Rotolo cruelly at Newport in 1963 when introducing her to his new lover, Baez; allowed him to accept credit for what seemed, to many listeners, other people’s arrangements; allowed him to cuff Billy James around when the guy was only doing his job; allowed him, through the decades, to phone in a good number of subpar concerts in addition to the sensational ones; and would allow him to go electric.

Chronicles: Volume One is a wonderful book, and a fascinating one. Dylan regularly recounts in its pages what might be considered by others to be embarrassing episodes, but there is very little or no remorse. The book is self-reflective, but it also has a well, that’s the way it is—that’s the way I am quality. Perhaps more to the point: You go your way and I’ll go mine.

But, of course, Dylan intended (or, while never admitting it, hoped) that an audience would go his way too—following him, moths to the flame, because of his irresistible dynamism and obvious brilliance. “It wasn’t money or love that I was looking for,” he writes. “I had a heightened sense of awareness, was set in my ways, impractical and a visionary to boot. My mind was strong like a trap and I didn’t need any guarantee of validity. I didn’t know a single soul in this dark freezing metropolis but that was all about to change—and quick.”

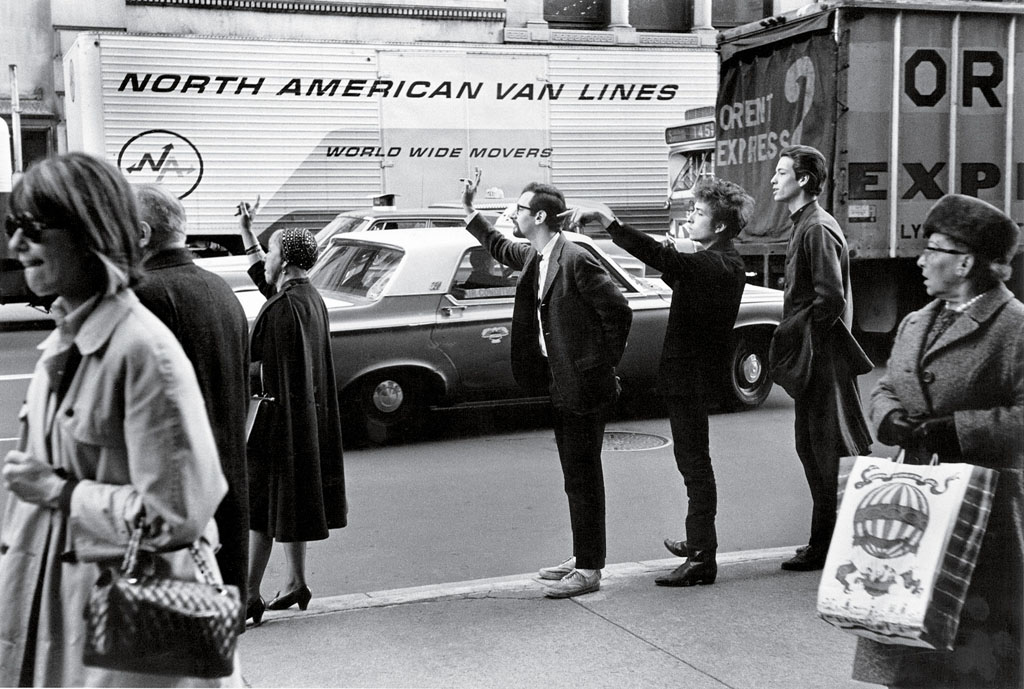

As we have already seen, it did change—very quickly indeed. Within a season, he became the folk darling of downtown. With Baez’s considerable help, he went national not too very long after shaking the dust of Hibbing off his jeans.

And now, what next?

Albert Grossman is a very interesting player in this saga. A hard-charging Chicagoan who sidled into the folk scene and started managing individuals and group acts, he hit it big with the trio Peter, Paul and Mary (he was pivotal in assembling the threesome in 1961) and would go on to promote the careers of Gordon Lightfoot, Richie Havens, the Band and Janis Joplin among others. Dylan signed with him in 1962. In Chronicles: Volume One the singer has a marvelous reminiscence of watching Grossman as he was trolling for talent at the Gaslight, the Greenwich Village folk mecca: “He looked like Sidney [sic] Greenstreet from the film The Maltese Falcon, had an enormous presence, dressed always in a conventional suit and tie, and he sat at a corner table. Usually when he talked, his voice was loud, like the booming of war drums. He didn’t talk so much as growl.” Dylan signed with him in 1962, despite the fact that Grossman took 25 percent of earnings versus the standard manager’s cut of 15 percent, Grossman’s rationale being that a client became 10 percent smarter the minute he or she spoke with him. Dylan, as always, was savvy about what he was entering into; he saw Grossman’s power and sway instantly. “He was kind of like a Colonel Tom Parker figure,” he says in Martin Scorsese’s No Direction Home, “you could smell him coming.” In the same film, John Cohen, one of the New Lost City Ramblers and an accomplished photographer who, as an integral part of the scene, was making memorable photographs of Dylan and other folkies in the early ’60s, says, “I don’t think Albert manipulated Bob, because Bob was weirder than Albert.”

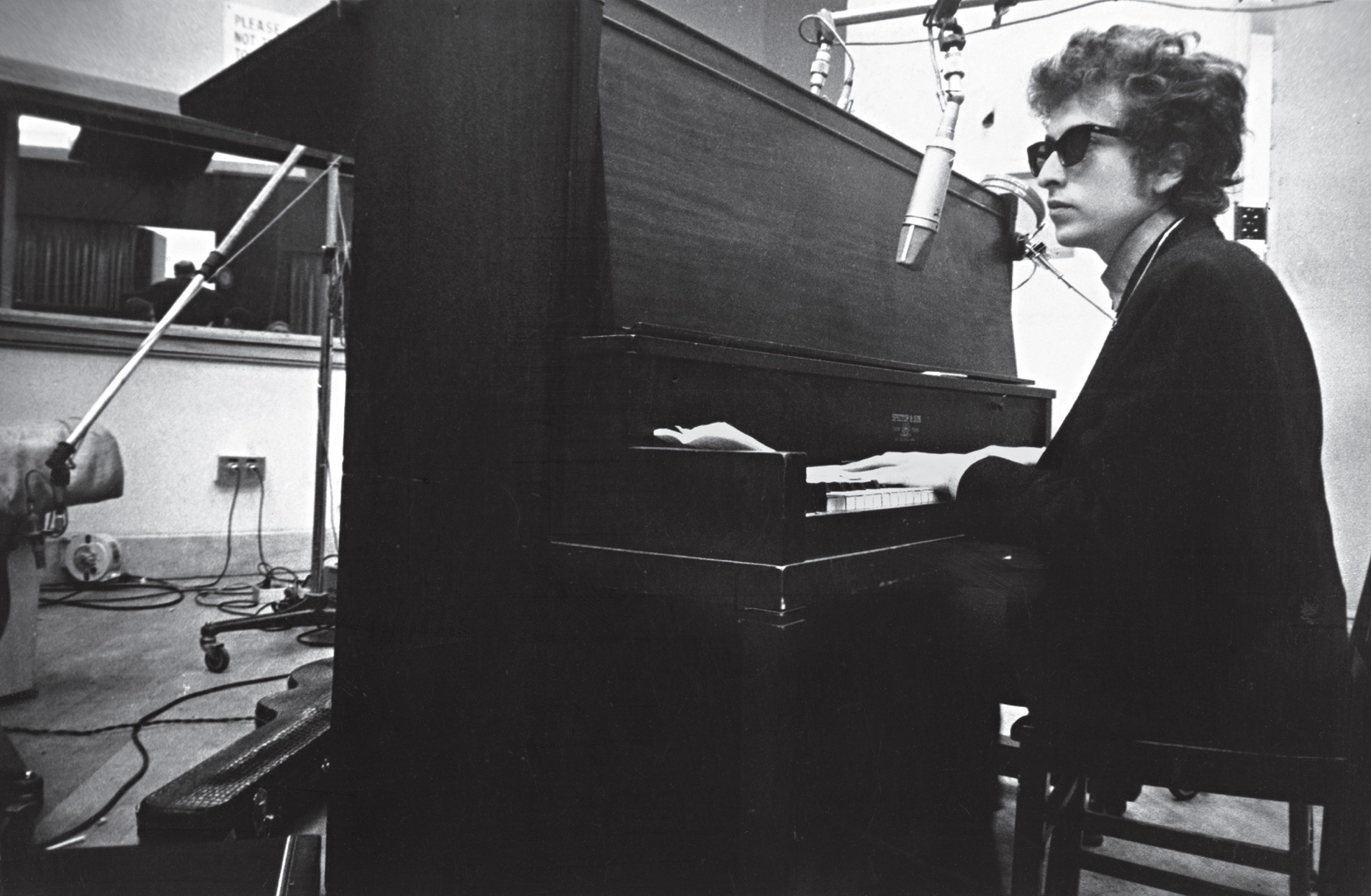

Which took considerable weirdness, a quality Dylan always possessed in deep quantities. Dylan knew what he was getting with Grossman, and in a sense turned him loose: a hired gun. Grossman didn’t like John Hammond, so halfway through The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan sessions, Hammond was replaced by the young African American producer Tom Wilson, who would help shepherd Dylan through four cuts on that record and then all of The Times They Are A-Changin’, Another Side of Bob Dylan, Bringing It All Back Home and the seminal 1965 track “Like a Rolling Stone,” regarded by many, including the magazine that bears the same name, as the very greatest cut in rock history.

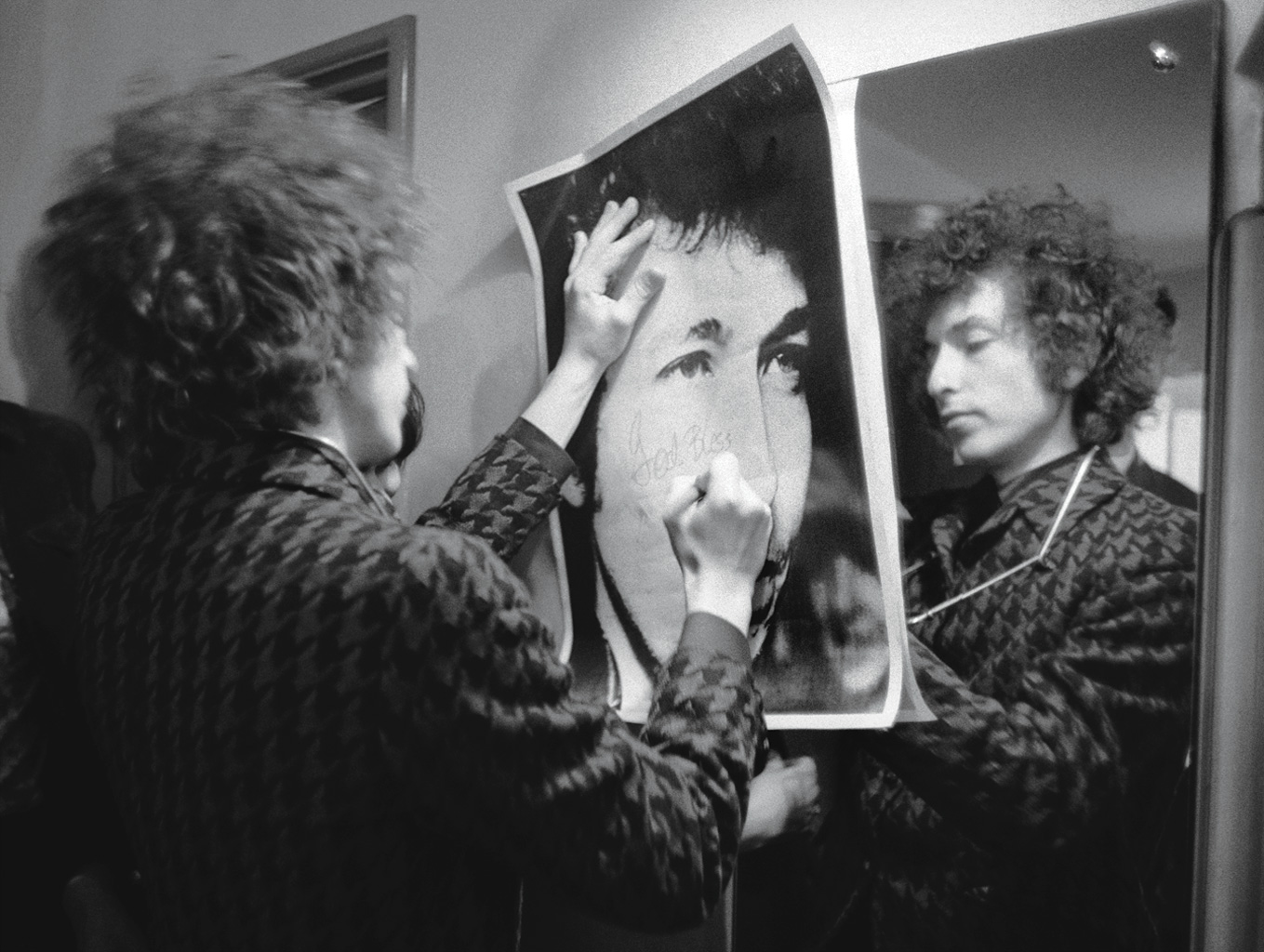

Skinny little Bob Dylan, with new friends like Joan Baez and Albert Grossman, was flexing his muscles. Grossman saw just how strong, determined and talented his new client was, and—no sweet-hearted Brian Epstein, he—started pushing people around in a manner not unlike that in which Dylan was manhandling the interviewers Grossman summoned forth. Perhaps the most famous example of the singer’s own bad behavior remains Dylan’s cruel taunting of a Time magazine London-based correspondent, Horace Freeland Judson, during the 1965 tour of England, an incident still remembered today because it was captured by documentarian D.A. Pennebaker’s camera and was included in the terrific 1967 film Dont Look Back. Pennebaker, who was well inside the Dylan orbit, observed the singer’s operation closely and with clear eyes, and later said of Grossman and his handling of the enterprise: “I think Albert was one of the few people that saw Dylan’s worth very early on, and played it absolutely without equivocation or any kind of compromise.”

In other words: The fans, the festivals, the press, the whole wide world could take Dylan on his and Albert Grossman’s terms, or not at all.

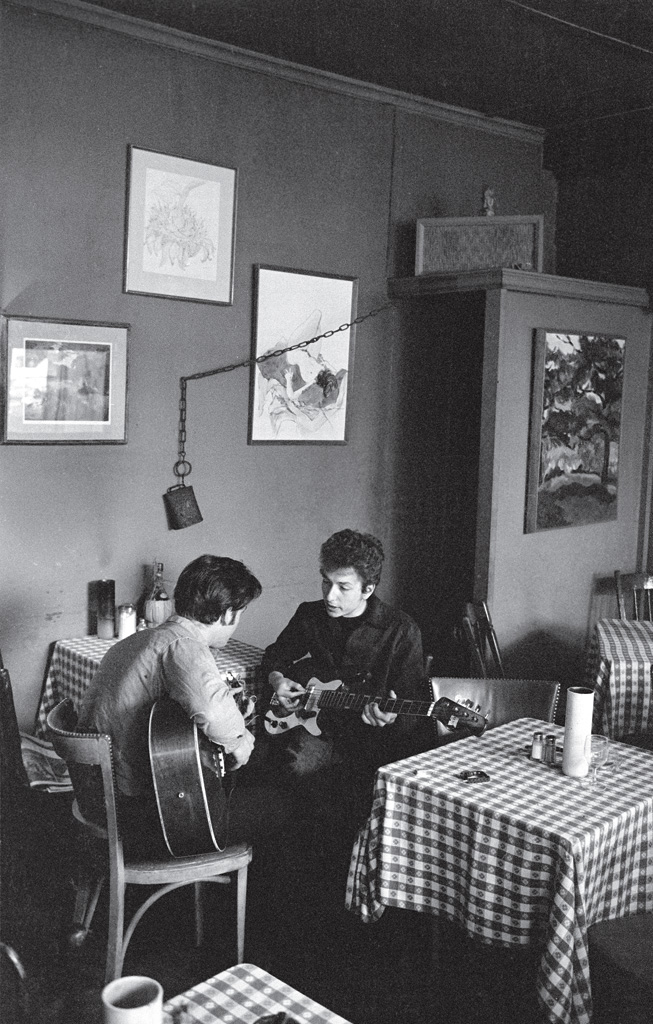

Dylan’s musical terms, beginning in 1964 and continuing through the recording of Bringing It All Back Home’s electric sessions in 1965, were changing rapidly. Lyrically, he was moving away from narrative tales and so-called protest songs wherein the message was more or less directly stated; he was, in his writing, becoming more abstract, opaque, allusive. In some songs, he wrote in a stream of consciousness vein clearly influenced by Jack Kerouac and his Beat Generation confreres.

In the summer of ’64 he spent much time out of the Greenwich Village orbit, staying often at Grossman’s place in the small upstate hamlet of Woodstock, where he could think and compose. Among the things he was thinking about, in a positive way, was the electric blues sound his friend John Hammond Jr. was working on in Chicago. (Just incidentally, Hammond, who was the son of producer John Hammond, had recruited for that effort a group that included three musicians who would be members of Dylan’s famous backing collaborative known first as the Hawks, later as the Band.) Dylan was restless with energy, recalled Joan Baez, who stayed with him that August at Grossman’s Woodstock home: “Most of the month or so we were there, Bob stood at the typewriter in the corner of his room, drinking red wine and smoking and tapping away relentlessly for hours. And in the dead of night, he would wake up, grunt, grab a cigarette, and stumble over to the typewriter again.” Late that month, Dylan traveled down to the city where he met the Beatles for the first time. The story is always told about how this summit influenced the Englishmen, who were turned on to marijuana by Dylan and subsequently began to look for a Dylanesque introspection and depth in their own compositions. But perhaps the inspiration cut both ways, as Dylan was already thinking about electric music and rock ’n’ roll, and now here were these super-popular moptops who were actually pretty fine fellows. (He and the Beatles would remain close; he and George Harrison would become something like best friends.)

A couple of the songs that would be featured on the largely acoustic Side Two of Bringing It All Back Home—“Gates of Eden,” “Mr. Tambourine Man”—had already been written but hadn’t made it onto Another Side of Bob Dylan. Now, on January 13, 1965, Dylan sat with Tom Wilson in Columbia’s Studio A in New York City and worked on, among others, eight songs that would be presented to a rock band over the following two days, “She Belongs to Me,” “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream” and “Love Minus Zero/No Limit” among them. On January 14, with no rehearsal, the band—three guitarists, including Dylan, a pianist, electric bass, drums—charged ahead. In only three and a half hours that afternoon, master takes of the three just mentioned songs plus “Subterranean Homesick Blues” and “Outlaw Blues” were waxed. Back in Studio A on the 15th, “Maggie’s Farm,” Dylan’s kiss-off to his protest-song disciples, was achieved in one take to kick off another memorable, fast-moving session, “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” and “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” being other classics addressed this day.

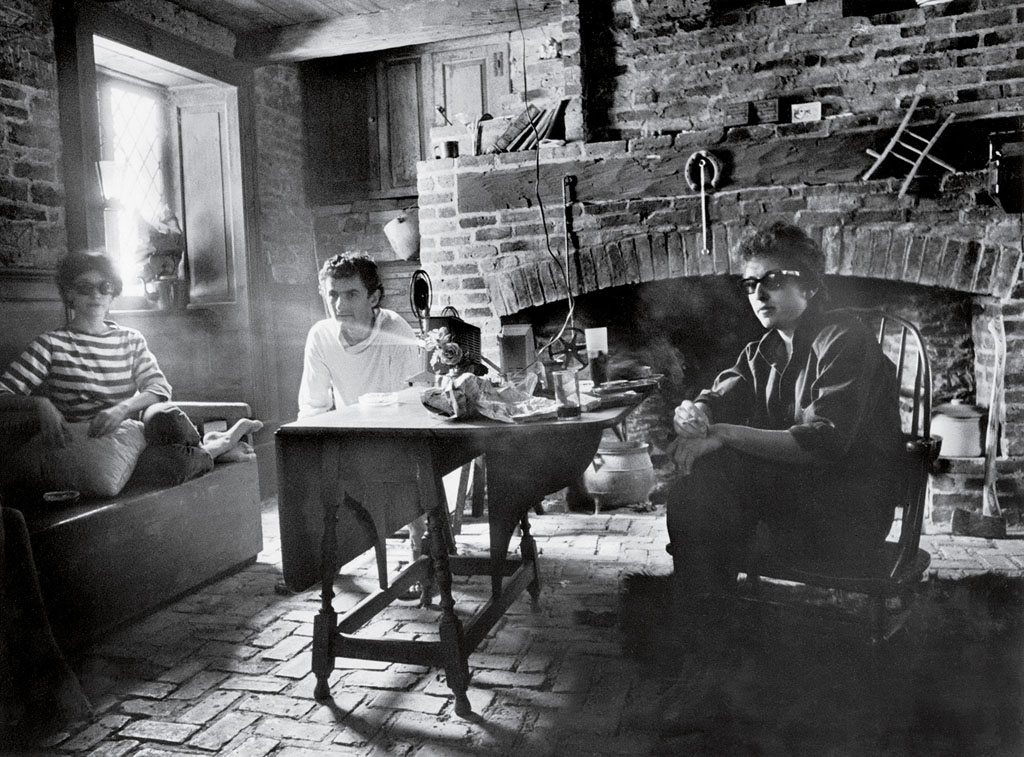

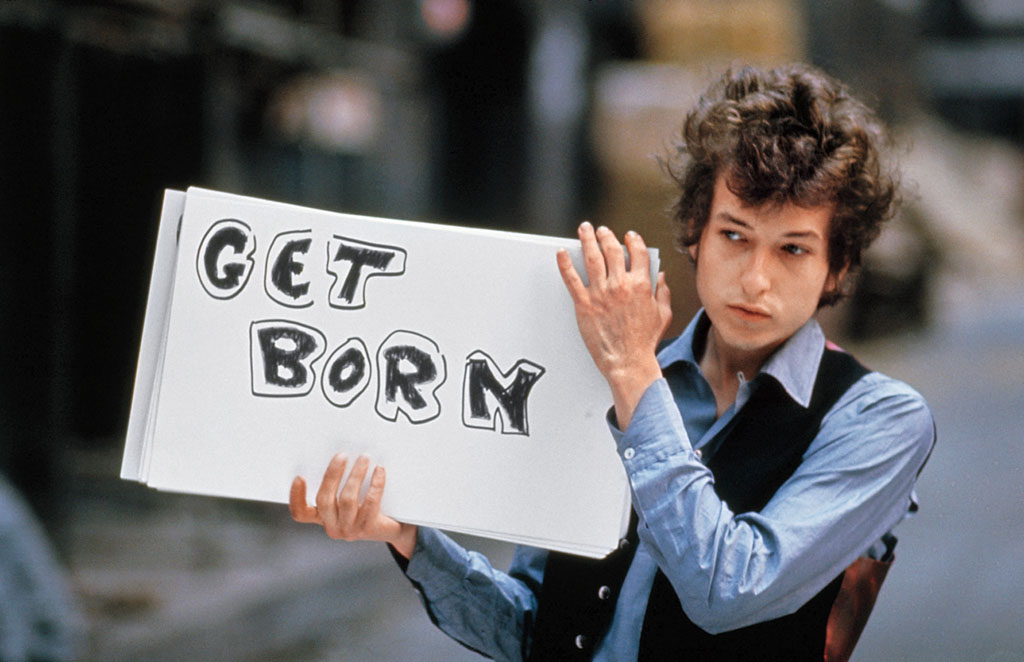

The album, which featured a cover photograph taken by Daniel Kramer at Grossman’s Woodstock home, with Grossman’s wife, Sally, lounging on a couch in the background, knocked people out, garnering Dylan thousands of new fans while alienating many old ones. “Subterranean Homesick Blues” became his first Top 40 hit in the United States and charted Top 10 in England, where the album went to Number One. (That single led to a pioneering music video when a sequence of Dylan tossing cue cards with lyrics from the song played during the opening of Dont Look Back; “Subterranean Homesick Blues” is also considered by some historians to be an early rap song.) Before Dylan ever took the stage as the headliner at Newport in the summer of ’65, the “trad folkie” phase of his career was emphatically erstwhile, and the masses were chattering away, pro and con.

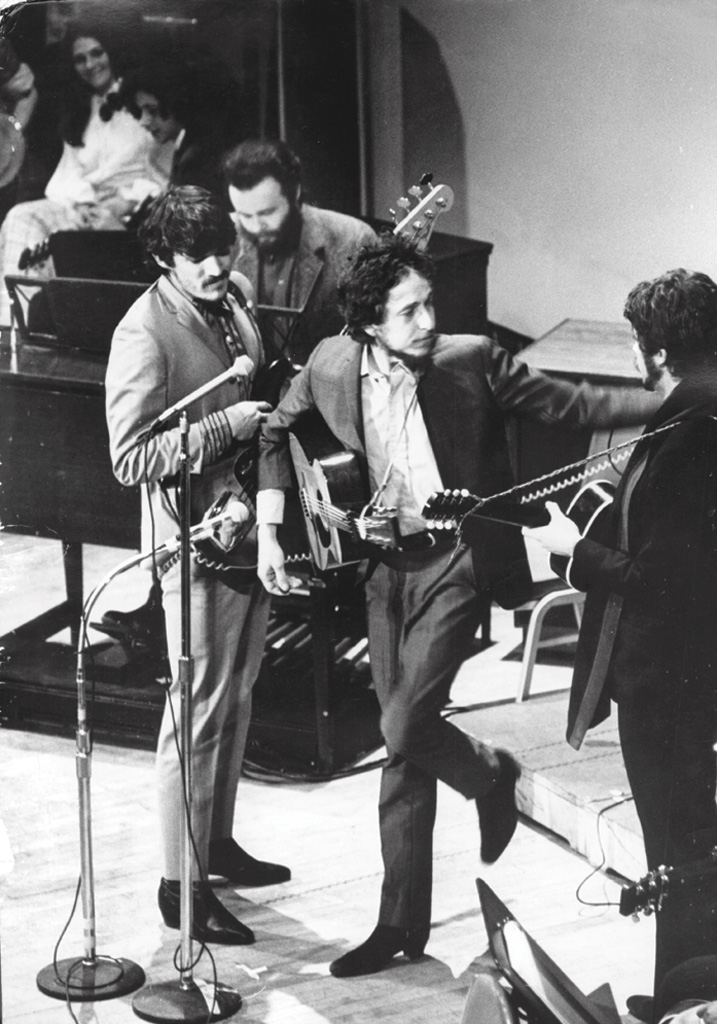

Dylan, now more famous than Baez, finished his most recent tour with her (he wouldn’t collaborate with her onstage again until the Rolling Thunder Revue concerts a decade further on, an altered relationship largely of his choosing) and made plans for his new live act. He hadn’t played an electric set since his r’n’r band had been silenced by the high school principal back in Hibbing, but now he would. His recruited sidemen for the Newport gig were largely members of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, including guitarist Mike Bloomfield. Dylan, who had performed three acoustic songs during a festival workshop earlier on July 24, apparently felt that Butterfield’s band was being dissed by Newport organizers—organizers who had invited them in the first place. He said, in effect: If they think they can keep electric music off this stage, they can’t. I’ll show ’em. He quickly assembled a pickup band that not only included Bloomfield but another who had recently helped him record “Like a Rolling Stone,” organist Al Kooper. In a marvelous clash of cultures, these ragtag renegades rehearsed that night in one of Newport’s legendarily opulent mansions dating from America’s Gilded Age.

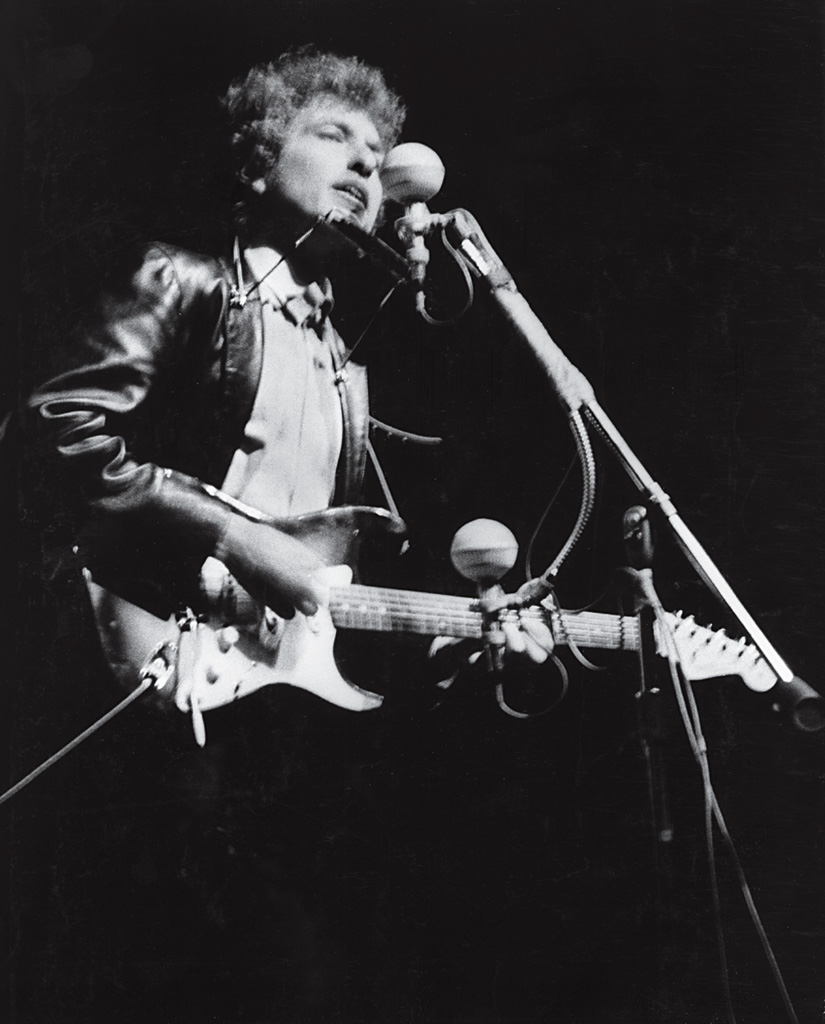

On Sunday night, introduced by Peter Yarrow of Peter, Paul and Mary, Dylan, like Bloomfield, took the stage with a solid-body electric guitar, and the rumblings began not just onstage. When the band launched into “Maggie’s Farm,” the boos issued forth, and they continued, intermixed with competitive cheering, through “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Phantom Engineer,” a prototype version of “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry.”

And then, that was it. Dylan and company left the stage, and the reaction was raucous. Yarrow begged him to return and Dylan did, but was upset. “What are you doing to me?” he asked Yarrow. He then asked the audience for a harmonica tuned in E, and a small shower of them pelted the stage. He performed, solo acoustic, “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.” Many in the audience who had missed the message of “Maggie’s Farm” still missed it with this closing number, and the response this time was rapturous. Dylan, for his part, wouldn’t return to Newport for 37 years.

There is a never-settled debate concerning the hostility exhibited at Newport: Was it largely due to a short set list, or to poor sound quality, or to the material (“tenth-rate drivel,” according to folksinger Ewan MacColl), or to the fact of electric music? Dylan surely bought into the final reason, and felt he had been betrayed by old friends and fans. Four days after returning to New York from Newport, he recorded “Positively 4th Street,” which seemed to promise that he would get his revenge on his former fellow travelers in the Village. If they wanted to see the future—at least, Dylan’s future—they only needed to consider that “Like a Rolling Stone,” a groundbreaking six-minute rock single, was at Number Two on the Billboard chart and was shaping the sound of a summer every bit as much as were the songs of Motown, the Beatles, the Stones and the Beach Boys. If it sold a couple fewer copies than the Kingsmen’s “Jolly Green Giant” by the time the year was out, and if that was folkdom’s rebuttal, well, so be it.

Not all of the old crowd deserted him. The late and great Dave Van Ronk, who always saw Dylan clearly even when he had cause to detest him for his aberrant and even unethical behavior, wrote in his posthumously published memoir: “I thought that going electric was a logical direction for Bobby to take. I did not care for all his new stuff, by any means, but some of it was excellent, and it was a reasonable extension of what he had done up to that point. And I knew perfectly well that none of us was a true ‘folk’ artist. We were professional performers, and while we liked a lot of folk music, we all liked a lot of other things as well. Working musicians are very rarely purists. The purists are out in the audience kibitzing, not onstage trying to make a living. And Bobby was absolutely right to ignore them.”

The latter half of 1965 was no less eventful than the first. In confirmation of Side One of Bringing It All Back Home came the album Highway 61 Revisited, with Bloomfield, Kooper and other rockers along for the ride, and the songs even more out there—the 11-minute “Desolation Row” but one example. Dylan was going to appear in support of the record and his new sound, and needed to cobble together a band. From the Highway 61 and “Like a Rolling Stone” sessions, he brought Kooper and bassist Harvey Brooks, adding to them members of that bar band called the Hawks—the same band John Hammond Jr. had been gigging with—and the guitarist Robbie Robertson and the drummer Levon Helm. He warned his associates before taking the stage at the Forest Hills Tennis Stadium on August 28 that the reaction might be less than friendly. Daniel Kramer, who was there, later remembered: “Dylan held a conference with the musicians who were going to accompany him in the second half of the concert. He told them they should expect anything to happen—he probably was remembering what occurred at Newport. He told them that the audience might yell and boo, and that they should not be bothered by it. Their job was to make the best music they were capable of, and let whatever happened happen.”

It happened, pretty much as it had at Newport. A contemporaneous report from Variety: “Bob Dylan split 15,000 of his fans down the middle at Forest Hills Tennis Stadium Sunday night . . . The most influential writer-performer on the pop music scene during the past decade, Dylan has apparently evolved too fast for some of his young followers, who are ready for radical changes in practically everything else . . . repeating the same scene that occurred during his performance at the Newport Folk Festival, Dylan delivered a round of folk-rock songs but had to pound his material against a hostile wall of anti-claquers, some of whom berated him for betraying the cause of folk music.”

Six days after the New York show, the reception was somewhat warmer out in laid back La La Land during a concert at the Hollywood Bowl, but the next year in England, now playing with four-fifths of what would become the Band (Levon Helm stayed home), hostility raised its head night after night. It was almost as if Dylan were courting complaint and controversy. Rather than just play an electric tour, where presumably the fans would know what they were paying for and could either show up or not, he repeated this format of opening the show with a folk guitar and harmonica, then switching to the rock-band numbers just as soon as he had the older fans swaying and smiling blissfully. Was he trying to upset them? Well, this was Bob Dylan, wasn’t it? This push-and-pull—this teasing and taunting, this pleasing the audience and then pissing it off—would reach a legendary (not to say, biblical) climax on May 17, 1966, late during a concert at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, England.

A man in the audience shouts to the stage, “Judas!”

“I don’t believe you,” Dylan responds. “You’re a liar!”

He then turns to his band, which is set to roar into “Like a Rolling Stone,” and orders: “Play it [expletive] loud!”

So in Dylan’s professional life, all is tempest, all is Sturm und Drang. In his personal life, post-Baez in late 1964 through 1965, all is bliss. Or a Dylan version of bliss.

He had first met the former Shirley Marlin Noznisky—born on October 28, 1939, in Delaware—in 1962, when, according to her family’s lore, she had been driving in Greenwich Village in her MG. She was, at the time, Sara Lowndes, married to magazine photographer Hans Lowndes (who had asked her to change her first name as well as her second: “I can’t be married to a woman named Shirley.”) Sara was a New York City career girl of a certain type: fashion model, stage actress when she could get a role, Playboy bunny when she needed a job. Her former stepson, Peter Lowndes, once said, “Her meeting with Bob was the reason [Sara left Hans Lowndes]—he was famous, and she was very beautiful.”

If she separated from Lowndes soon after meeting Dylan, she and the singer would not become a couple for a while more—and not until Dylan had progressed through his relationships with Suze Rotolo and Baez. When, in late 1964, Dylan and Sara did get serious, they took apartments in the storied Chelsea Hotel in New York City to be near one another. By 1965, Bobby and Sara were living together in a cabin in Woodstock, and that living was easy. He wrote “Like a Rolling Stone” in a heartbeat there: “It just came, you know.”

Not long after the Hollywood Bowl concert, Dylan and Sara wed, on November 22, 1965, in a civil ceremony that was small and secret. (Dylan lied for a time to even close friends about having married, and it fell to Nora Ephron to make the news public the following February in a New York Post story headlined, HUSH! BOB DYLAN IS WED.) Exchanging vows in Mineola, Long Island, Dylan had only Albert Grossman in his wedding party and Sara had only her maid of honor.

Sara was content to suppress her ego in deference to her star husband and his career—she had little in common, in this vein, with Linda McCartney, Pattie Boyd or Yoko Ono—but she was sometimes involved. She had already been instrumental before their marriage, for instance, in the Pennebaker documentary Dont Look Back. In fact, Pennebaker told biographer Robert Shelton, “The idea of the film was from his wife.” Sara, after bringing Pennebaker in contact with Dylan and Grossman, continued to serve as a liaison on that production. But mostly, when it came to Dylan’s music, Sara served as muse. She was, in 1966, the “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands,” a song Dylan once told Shelton he considered perhaps his best. A decade later, in a plea for reconciliation after their marriage had failed, she was overtly the “Sara” on the Desire album. Those things we know for sure. It has also been speculated that Sara was at the heart of such songs as “Isis,” “We Better Talk This Over,” “Abandoned Love,” “Down Along the Cove,” “Wedding Song,” “On a Night Like This,” “Something There Is About You,” “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight,” “To Be Alone with You,” “If Not for You,” and those classics from the 1965 output: “Desolation Row” and “Love Minus Zero/No Limit.” If the consensus opinion that 1975’s Blood on the Tracks, with its recurring themes of loss, heartache and anger, represents perhaps the greatest breakup album of all time—an opinion Dylan refutes, insisting the songs were inspired by Chekhov short stories—then Sara’s legacy extends. Jakob Dylan, the singer, dismisses his dad’s demurral, asserting at one point to The New York Times, “When I’m listening to ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues,’ I’m grooving along just like you. But when I’m listening to Blood on the Tracks, that’s about my parents.”

In the 10 years between the romance of Bringing It All Back Home and the recrimination of Blood on the Tracks, the Dylans lived in Woodstock—also back in New York City, out in Malibu, but often in Woodstock—and raised a family that would come to include their own four children, Jesse, Anna, Samuel and Jakob, plus Sara’s daughter from her marriage to Lowndes, Maria, whom Dylan adopted. When at home, Dylan tried to live a sheltered existence, and Sara—as said, a rarity among rock star wives—stayed thoroughly out of the public eye. Still today, after so much effort has been put into unearthing Dylaniana through the decades, relatively little is known about Sara. In the song that bears her name, Dylan calls her “radiant jewel, mystical wife,” and there is certainly something of the spiritual to her image. It has been said that Dylan relied on her for the kind of guidance one might seek from an occultist; Sara would suggest when it was propitious to travel, and when it wasn’t. Lynn Musgrave was a music journalist living in Woodstock, and knew Sara. She told Shelton, “She is not Mother Earth in the heavy way, but she just rolls with nature. She has a low center of gravity, if not quite indestructible, then something close to it. That is what it must take to sit up there in Woodstock, being married to Dylan and never going out much. I don’t think she complains much, either. I got the impression of her being strong. That line, ‘she speaks like silence’—that’s Sara.” Shelton himself met Sara in 1968 at the first public function she attended with her famous husband, a tribute to Woody Guthrie at Carnegie Hall, and later wrote, “mostly on her own, [she] moved about rather shyly, gravitating toward people she knew from Woodstock. She appeared demure, yet slightly ill at ease in a throng fascinated by her husband. I chatted briefly with her, and noted the deep large eyes, the glowing complexion, the air of quiet detachment. Friends of Sara considered her then as extremely warm and devoted toward a select few.”

Her devotion to Dylan lasted until the mid-1970s and was followed by a bitter divorce, not finalized until 1977. To deal with all that now would be getting ahead of ourselves; that is material for the next chapter, and the one beyond that. Right now, we are still with the happily newlywed Dylans, 1965 is giving way to a new year, Dylan is determined to push his new sound upon his audience, and there is a new album coming out.

If The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, The Times They Are A-Changin’ and Another Side of Bob Dylan represented the artist’s first great triptych—and if Time Out of Mind, Love and Theft and Modern Times represent a recent one—then Dylan’s second group of three sibling albums, each of them a peak in his considerable creative output and featuring the “wild, mercury sound” that was then his quest, comprised Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde. This last one, an unprecedented double-album set that included “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” as the entirety of Side Four, also gave the world “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35,” “I Want You,” “Just Like a Woman,” “Visions of Johanna” (an eternal masterpiece, which Dylan wrote while living in the Chelsea Hotel with his pregnant wife) and several others. It was recorded in Nashville with seasoned musicians, after Dylan, Robbie Robertson and Al Kooper had arrived from New York with this bushel of new songs. Blonde on Blonde pushed the music further, and now folk, rock and country, too, were all in the mix.

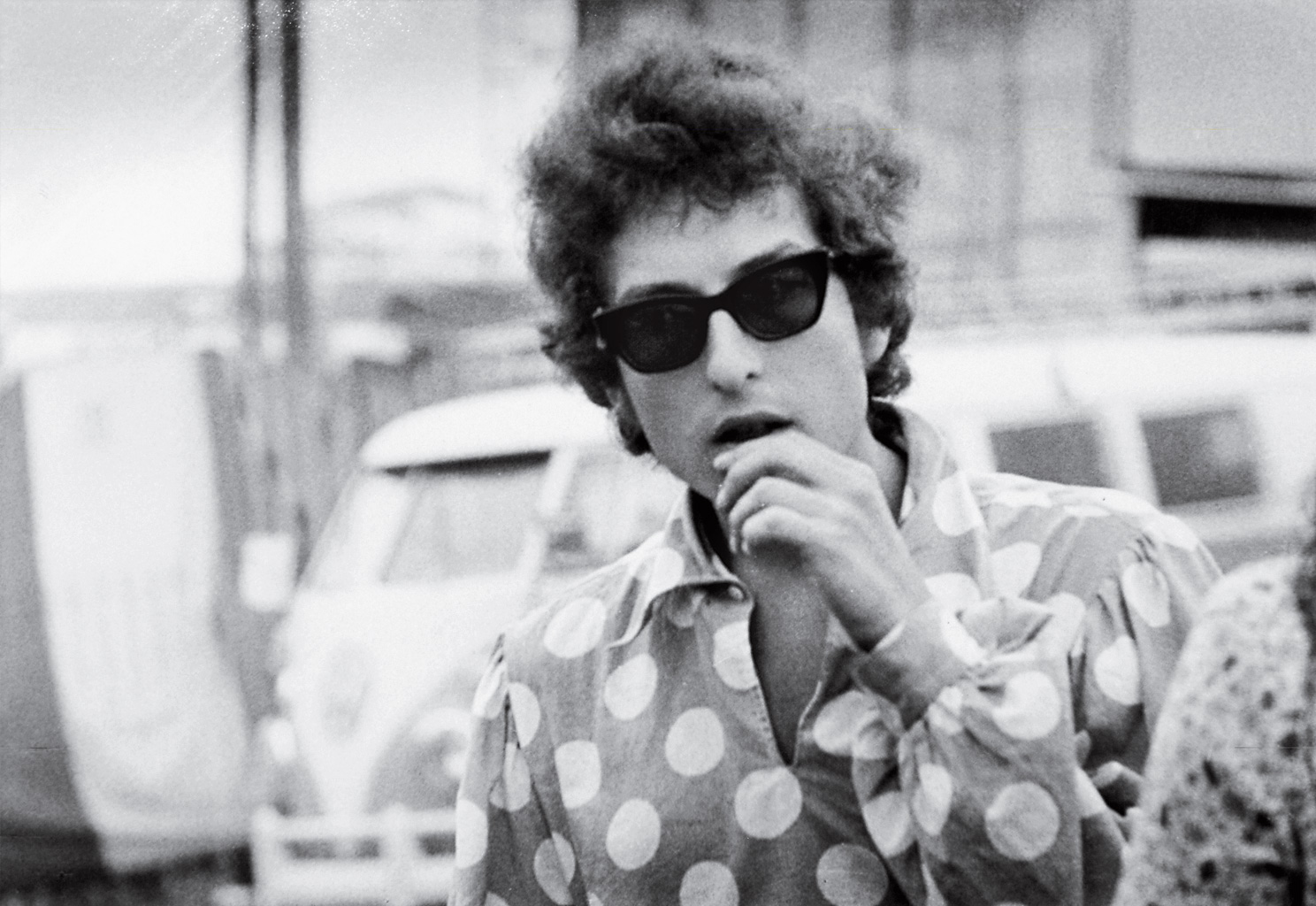

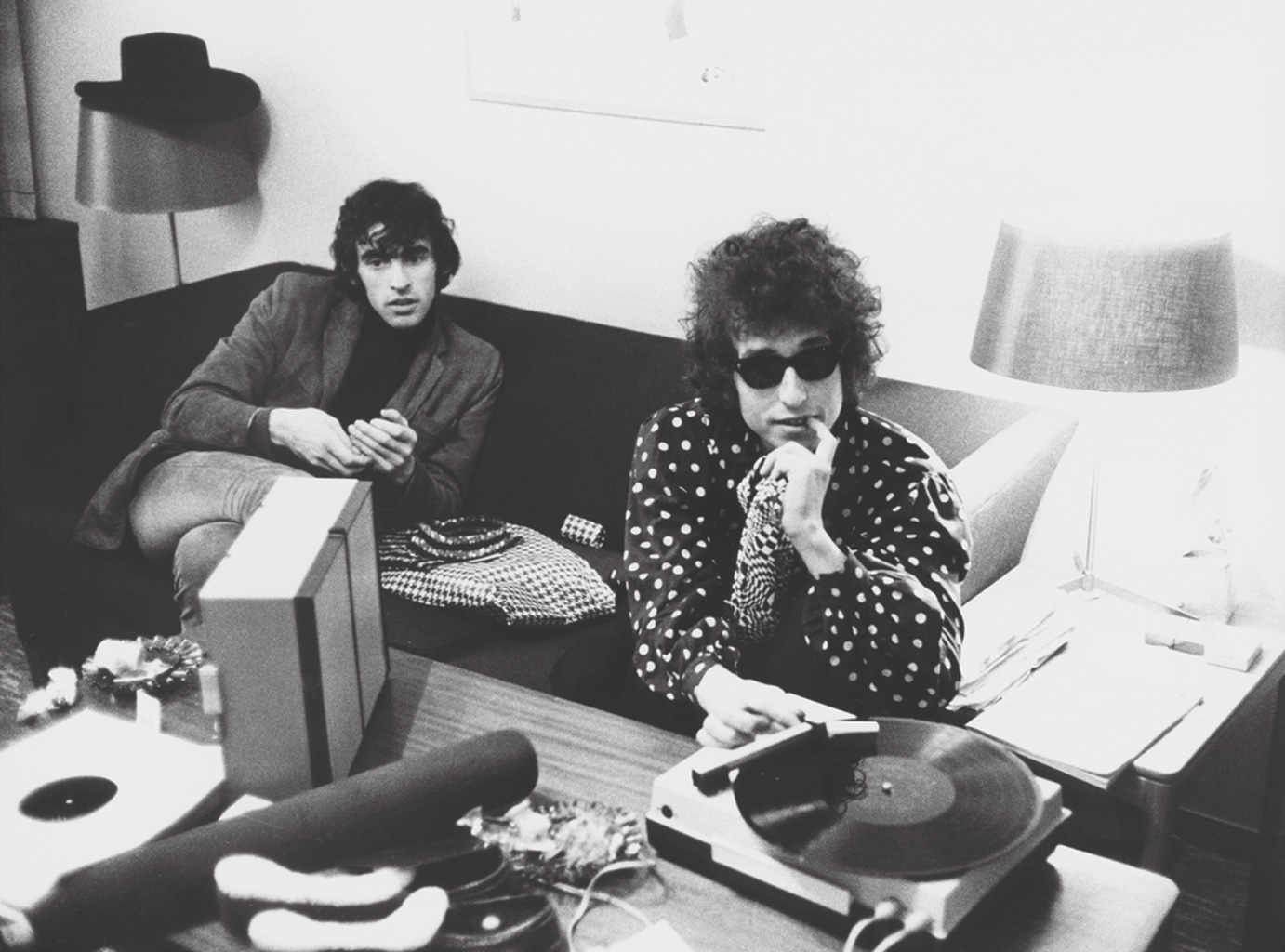

By the time it was released in the spring of 1966, Dylan and his backing band the Hawks were in Australia being chided and derided on a daily basis in the press and on a nightly basis in the auditorium. Dylan was wearing those Beatle boots, shirts as outrageous as his hair and 24/7 sunglasses. He was also not responding well to the pressure and venom and was, according to D.A. Pennebaker, who was still hanging around with his camera, “taking a lot of amphetamine and who-knows-what-else.”

“I was on drugs, a lot of things,” Dylan later admitted to Rolling Stone’s Jann Wenner, “just to keep going, you know? . . . I was on the road for almost five years. It wore me down.” But he persevered, moving through Europe and toward England.

It’s interesting: Judged not by total sales but by chart position, Dylan’s early folk records had been more popular in Great Britain than in his homeland, even though many of his topical songs were directed at life in the United States. The acoustic Dylan was a god to British folkies, and his 1965 tour had been an unequivocal triumph. Now came this wise-guy, would-be rocker—a Mick Jagger manqué who couldn’t pull it off, and who refused to sing what the audience wanted, refused to explain himself and refused to give anyone a straight answer to anything. His February 1966 interview in Playboy, conducted more or less cordially by the respected music writer Nat Hentoff, remains the classic of its kind mostly because Hentoff decided early (and wisely) to play the straight man, and allow Dylan to entertain in his way. Dialogue taken verbatim from this interview was used as the absurdist lines voiced by Cate Blanchett in the acclaimed 2007 filmic Dylan rumination by Todd Haynes, I’m Not There. A representative exchange from the original interview:

PLAYBOY: Mistake or not, what made you decide to go the rock ’n’ roll route?

DYLAN: Carelessness. I lost my one true love. I started drinking. The first thing I know, I’m in a card game. Then I’m in a crap game. I wake up in a pool hall. Then this big Mexican lady drags me off the table, takes me to Philadelphia. She leaves me alone in her house, and it burns down. I wind up in Phoenix. I get a job as a Chinaman. I start working in a dime store, and move in with a 13-year-old girl. Then this big Mexican lady from Philadelphia comes in and burns the house down. I go down to Dallas. I get a job as a “before” in a Charles Atlas “before and after” ad. I move in with a delivery boy who can cook fantastic chili and hot dogs. Then this 13-year-old girl from Phoenix comes and burns the house down. The delivery boy—he ain’t so mild: He gives her the knife, and the next thing I know I’m in Omaha. It’s so cold there, by this time I’m robbing my own bicycles and frying my own fish. I stumble onto some luck and get a job as a carburetor out at the hot-rod races every Thursday night. I move in with a high school teacher who also does a little plumbing on the side, who ain’t much to look at, but who’s built a special kind of refrigerator that can turn newspaper into lettuce. Everything’s going good until that delivery boy shows up and tries to knife me. Needless to say, he burned the house down, and I hit the road. The first guy that picked me up asked me if I wanted to be a star. What could I say?

And the interview went on and on in this vein, concluding with:

PLAYBOY: One final question: Even though you’ve more or less retired from political and social protest, can you conceive of any circumstance that might persuade you to reinvolve yourself?

DYLAN: No, not unless all the people in the world disappeared.

Playboy magazine was, even back in the day, able to cross the Atlantic—the British said they liked it for the articles, essays and short stories—and by the time Dylan stepped foot in the kingdom on this tour, Newport and Playboy were both on the table, and the knives were out. None of what followed went well, the “Judas” allegation in Manchester being only the most enduring moment. The Royal Albert Hall shows in London were perhaps the most dispiriting. Dylan mixed it up with his accusers, seldom a sound strategy for rapprochement, and the situation devolved, with the Beatles at one point shouting from their box to others in the audience, “Leave him alone—shut up!”

In May 1966, Dylan and the Hawks returned to America, beaten if not quite broken. All Dylan wanted was rest, a slower speed. Woodstock looked, in his imagining, to be the answer for the next little while—Sara, the baby, et cetera. But he soon learned that Woodstock, and whatever it represented in his mind, would have to wait. ABC was eager for a documentary film of the world tour that had been contracted earlier. The Macmillan publishing firm was pointing to a deadline for an agreed-upon book (which would end up being the narrative poem Tarantula). Grossman handed Dylan an itinerary of tour dates that he had set up for the rest of the summer, extending into autumn.

The late Robert Shelton, a journalist who made the journalist’s mistake of growing too close to his subject, remembered in his 1986 book, No Direction Home: “Late Friday night, July 29, I received a telephone call from Hibbing. Dylan’s father sounded distraught: ‘They just called me from the radio station here. They said they had a news bulletin that Bob’s been badly hurt in a motorcycle accident. Do you know anything about it?’ I said this was the first I had heard of it. ‘The Grossman office won’t help me one bit on this,’ said Abe. ‘And I can’t get through to Sara. Would you please see if you can find out something—anything—and call us back, collect? Bob’s mother is very worried—and so am I.’ Four months earlier, a similar phone call had informed me of [folksinger Richard] Fariña’s death in a motorcycle accident. I rang The New York Times for more information.” Shelton soon learned: “Details about Dylan’s accident . . . were not easy to ascertain. It was widely reported that Dylan nearly lost his life. To me, it seems more likely that his mishap saved his life. The locking of the back wheel of Dylan’s Triumph 500 started a chain of redemptive events that allowed him to slow down.”

No ambulance had been called to the scene; Dylan hadn’t been admitted to any hospital. Dylan has said that he broke several vertebrae in the crash, but there is no injury report. What happened?

The suggestion has been made that Dylan, faced with unrelenting pressure of his own initial making, panicked, and perhaps spun out with something approaching purposefulness. Dylan, for once, will not argue the point, and has written in Chronicles: Volume One—which is as elliptical as it wants to be, when it wants to be—“I had been in a motorcycle accident and I’d been hurt, but I recovered. Truth was I wanted to get out of the rat race.”

He convalesced in Woodstock.

He ate better, and dressed more casually.

He and Sara continued to build their family.

He would occasionally turn up for a benefit concert or surprise appearance, but essentially he retired from the stage for most of the next decade.

He found it more difficult to write songs.

He thought about becoming more serious about his painting.

If he wondered what the future of Bob Dylan might be, well, to this day he still hasn’t admitted to that.