Chapter 1

Planning Your Project

In This Chapter

Choosing the right finish for the job

Choosing the right finish for the job

Playing it safe with lead paint

Playing it safe with lead paint

Estimating how much paint you need

Estimating how much paint you need

Selecting the right applicators

Selecting the right applicators

Using the proper brushing, rolling, and spraying techniques

Using the proper brushing, rolling, and spraying techniques

W ith good preparation and planning, any job — big or small — will go smoothly, and you’ll reap the rewards of an attractive, long-lasting finish. This chapter walks you through the stages of planning a painting project, from selecting a finish to buying the right amount of paint to finding the best technique for the surface you’re painting.

A Primer on Finishes

The greatest hurdle you’re likely to face isn’t on your walls or ceilings; it’s in the aisles of your home center. Faced with mile-long shelves stacked to the ceiling with paints, stains, and other finishing products, you may stand there musing, “How the heck do I know what kind to buy?”

Water-based or oil-based?

When you reach the paint department, you face a choice between the two major types of paints, stains, varnishes, and other clear coatings: alkyd (oil-based) and latex (water-based). Alkyd paint produces more durable and washable surfaces, but because cleaning up afterwards involves using paint thinner (or mineral spirits ), it isn’t as user-friendly. Some professional painters insist on using alkyd paint, however, claiming that it’s more durable in demanding situations.

Latex paint is the more popular choice because it’s much easier to work with and cleans up with soap and water. For first-time painters, latex is the better choice because you get a professional-looking job with a durable finish. Plus, latex paint dries quickly and produces fewer odors.

First things first: Primers and sealers

Base coats include primers, sealers, and combination primer-sealers. You apply a base coat under a topcoat (a finish that protects and sometimes colors the surface) to provide better adhesion and/or to seal the surface for a more even application of the finish, or in some cases to prevent stains from bleeding through the topcoat.

Certain topcoats don’t require a primer when used on certain surfaces. For example, you don’t need to prime when you’re recoating well-adhered paint with an identical paint (latex semi-gloss over latex semi-gloss, for example) and you’re not making a significant color change. Fortunately, you don’t need to remember these rules — just read the label on the can of topcoat paint. It will specify primer requirements, if any, for various surfaces.

Primers

Primers are formulated to adhere well to bare surfaces and provide the best base for other paint to stick to. Water- and oil-based primers are available for virtually all interior and exterior surfaces. Before you paint, you need to prime all unpainted surfaces, patched areas, and spots that you make bare in the preparation stages.

Most primers (also called undercoaters ) contain little pigment and none of the ingredients that give topcoats shine, durability, and washability. Apply topcoats as soon as possible after the primer dries. (Primer generally dries fast.) Some primers can be top-coated after as little as an hour.

Sealers and primer-sealers

You should use a sealer or primer-sealer if you’re painting a material that varies in porosity, such as newly installed drywall or a wood such as fir. The seal prevents the topcoat from being absorbed unevenly, which would give the finish a blotchy appearance or an uneven texture. Sealers also block stains. If you have kids, for example, you may have marker or crayon stains on your walls. To prevent bleed-through, apply a stain blocker, stain-killing sealer, or white-pigmented shellac. These primer-sealers are available in spray cans for small spots and in quart and gallon containers for large stained areas. Also use them to prevent the wood knots’ resin from bleeding through the topcoat.

Categorizing finishes

Sorting through the myriad choices of topcoats — one manufacturer’s catalog we looked at listed hundreds of finishes in 90 categories — isn’t as difficult as it may seem at first. You see, for example, that most fall into one of the following categories:

Exterior paints

are formulated to withstand the effects of weather, damaging ultraviolet radiation, air pollution, extremes in heat and cold, expansion, and contraction. They include house paints (intended for the body of the house but may be used for trim), trim paints, and a variety of specialty paints, such as those for metal roofs, barns, aluminum or vinyl siding, and masonry surfaces.

Exterior paints

are formulated to withstand the effects of weather, damaging ultraviolet radiation, air pollution, extremes in heat and cold, expansion, and contraction. They include house paints (intended for the body of the house but may be used for trim), trim paints, and a variety of specialty paints, such as those for metal roofs, barns, aluminum or vinyl siding, and masonry surfaces.

.jpg)

You can use some exterior paints indoors (read the label), but they aren’t designed to hold up to scrubbing as well as some interior paints are. Never use an interior finish outdoors.

Interior paints include flat ceiling paints, wall and ceiling paints in a range of sheens from flat to gloss, trim paints, and enamels in higher gloss ranges. Consider using special interior paints that contain fungicides for high-humidity areas such as kitchens, bathrooms, and laundry rooms. Interior textured paints, intended for use on ceilings and walls, contain sand or other texturing materials. Use vapor-retarding paint on interior walls in homes that have had thermal insulation blown into wall cavities without the required vapor retarder.

Interior paints include flat ceiling paints, wall and ceiling paints in a range of sheens from flat to gloss, trim paints, and enamels in higher gloss ranges. Consider using special interior paints that contain fungicides for high-humidity areas such as kitchens, bathrooms, and laundry rooms. Interior textured paints, intended for use on ceilings and walls, contain sand or other texturing materials. Use vapor-retarding paint on interior walls in homes that have had thermal insulation blown into wall cavities without the required vapor retarder.

Interior/exterior paints can be used indoors or out. Some alkyd, urethane, and water-based floor, deck, and patio enamels fall into this category.

Interior/exterior paints can be used indoors or out. Some alkyd, urethane, and water-based floor, deck, and patio enamels fall into this category.

Interior and exterior stains are formulated for interior, exterior, or interior/exterior use. Although people associate stains primarily with wood, stains are also available for concrete. Stains intended for interior applications offer little or no protection and must be top-coated with a protective, film-forming sealer finish such as varnish, or with a separate sealer and a wax or polish. Exterior stains have water-repellent and UV-reflecting qualities.

Interior and exterior stains are formulated for interior, exterior, or interior/exterior use. Although people associate stains primarily with wood, stains are also available for concrete. Stains intended for interior applications offer little or no protection and must be top-coated with a protective, film-forming sealer finish such as varnish, or with a separate sealer and a wax or polish. Exterior stains have water-repellent and UV-reflecting qualities.

Transparent finishes are just that: transparent, not colorless. Alkyd and polyurethane varnishes are amber colored and will yellow further with time. Polyurethane varnish has largely replaced alkyd varnish because it’s more moisture and stain resistant.

Transparent finishes are just that: transparent, not colorless. Alkyd and polyurethane varnishes are amber colored and will yellow further with time. Polyurethane varnish has largely replaced alkyd varnish because it’s more moisture and stain resistant.

Water-based clear finishes dry three to six times faster than alkyds. Milky, water-borne polyurethane varnish and water-borne acrylic finish dry clear and remain clear, so they’re excellent choices for use over pickled, pastel-stained, or painted surfaces. On the downside, they lie on the surface rather than penetrate, so they don’t enhance or bring out the beauty of the natural wood as well as penetrating finishes do. Nor do they offer the stain and water resistance of oil-based finishes.

One-step stain-varnish combos stain, seal, and protect in one coat. They don’t penetrate wood well and are hard to maintain, so we recommend that you stick with the two-step approach.

One-step stain-varnish combos stain, seal, and protect in one coat. They don’t penetrate wood well and are hard to maintain, so we recommend that you stick with the two-step approach.

A varnish offers more protection than other sealer/finish approaches, such as shellacs, oils, and polishes. However, varnish masks the beauty of the wood more than these alternatives do, so it isn’t often used on fine furniture. Furniture oils, such as tung oil, boiled linseed oil, and Danish oil, are penetrating, wipe-on finishes with an amber color and a satin luster. Oils offer little moisture or stain resistance, but you can easily conceal scratches by recoating. This quality makes oils a good choice for wood that takes a beating — but only if stains and water aren’t big concerns.

Specialty finishes, including some primers, sealers, and topcoats, are formulated for specific and usually demanding applications. Whenever a project seems to go beyond the basics, look for specialty products. Primers are made for galvanized metal and mill-finish aluminum. Masonry sealers prevent dusting or leaching of alkalis. Two-part epoxy and two-part urethane paints are used when a particularly strong bond is required or when a finish must stand up to extreme abuse, such as on countertops or garage floors.

Specialty finishes, including some primers, sealers, and topcoats, are formulated for specific and usually demanding applications. Whenever a project seems to go beyond the basics, look for specialty products. Primers are made for galvanized metal and mill-finish aluminum. Masonry sealers prevent dusting or leaching of alkalis. Two-part epoxy and two-part urethane paints are used when a particularly strong bond is required or when a finish must stand up to extreme abuse, such as on countertops or garage floors.

Lead, the Environment, and You

Lead, an extremely toxic substance, was present in most paints produced before the late 1970s, when its use was banned. An estimated 75 percent of homes built before 1978 contain lead-based paint. If your home has lead-based paint, exercise caution whenever you make repairs around the house.

We have no doubt that this advice is sound for most people and a virtual no-brainer for large projects, such as stripping all the paint off your exterior siding or interior trim. On the other hand, we recognize — as does the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency — that it’s neither practical nor realistic to expect homeowners not to work on certain smaller projects just because they involve lead paint. In fact, two EPA booklets describe how to go about it: Protect Your Family in Your Home and Reducing Lead Hazards When Remodeling Your Home . Call 1-800-424-LEAD to have the material mailed or download materials directly from the NLIC Web site: leadctr@nsc.org .

.jpg)

Choosing an Exterior Finish

Unless you’re building a new home or re-siding an existing one, your choices for what finish to use are dictated to a degree by your siding and the type and condition of any existing finish. For example, some finishes work better on smooth, painted wood, and others work better on rough, stained wood. So the first step is to narrow the options to the appropriate finishes. Next, choose the ones that offer you the right combination of qualities. Finally, choose a color.

Paint versus stain

If you have new siding or siding that has been treated only with a semitransparent stain, your options are wide open. However, you can’t stain over previously painted surfaces.

As a general rule, paint is the preferred finish for smooth siding, trim, and metal siding like steel or aluminum. It offers maximum protection from UV radiation and moisture. Stains are commonly used on natural wood siding, especially rough-sawn boards, and on other exterior wood surfaces, such as decks and fences.

Although paint lasts longer than stain, paint finish builds up and may peel or otherwise fail. If it does, you’re in for a lot of work. Stains, on the other hand, may not last as long, but thanks to the penetration, they just weather away. Over the long haul, less cost and work may be involved if you choose stain. It’s easier to apply, and preparation is usually limited to simple power washing.

Exterior latex paint

Latex is the hands-down favorite for most painted exterior surfaces. It’s popular because it’s easier to use and more environmentally friendly than oil-based paint. Latex paint is more elastic and remains flexible, so it won’t crack as the materials to which it’s applied expand and contract. Oil-based paint, on the other hand, becomes brittle with age. Latex paint has superior color retention over most oil-based paint — it doesn’t fade as much. The paint film also permits interior moisture vapor to pass through, so latex paint is less likely to peel due to moisture problems. You can apply a latex topcoat over either latex or oil-based primer.

Exterior alkyd paint

On a few surfaces, alkyd (oil-based) paint may be a better choice than latex. For example, if a house has numerous coats of alkyd paint, it’s generally best to stick with alkyd. Believing that alkyd-painted surfaces are generally easier to clean and have more sheen than latex paints, some professionals use latex on the body of the house but prefer to use an alkyd finish on trim or other high-contact areas, such as doors. We think that the advantages of latex outweigh the purported advantages of alkyd-based paint in the vast majority of applications. We’re inclined to agree with the professionals, however, who say that alkyd paints, especially primers, are better to use on problem areas.

.jpg)

Exterior stains and clear coatings

Stains and clear coatings are the most natural-looking protective finishes for wood. Exterior stains and varnishes have fungicides, offer greater ultraviolet (UV) protection than interior versions, and may have more water-repellent qualities, too. Stains are available in both oil- and water-based versions and are colored with dye and pigment. A semitransparent stain uses more dye for deep penetration but allows the wood grain to show. A solid-color stain uses more pigment to cover all existing color and grain but retains some textures and contains a sealer, such as urethane or varnish. A solid-color stain offers better UV protection and hiding characteristics than semitransparent stain or transparent finishes, such as varnish. Solid-color stain penetrates more than paint and produces a thinner film, so it isn’t as likely to peel.

You can only apply stains over new or previously stained surfaces — not painted ones. Oil-based semitransparent stains are a good choice for new wood siding, decks, and fences. These stains have a linseed-oil base, which offers good penetration of new wood (especially rough-sawn surfaces) while revealing the wood’s grain and texture. For best protection, use two coats of semitransparent stain on new wood surfaces.

If your goal is to conceal discoloration, solid-color stains have more pigment than semitransparent stains and tend to hide the wood grain. This characteristic makes solid-color stains a better choice to finish pressure-treated wood that has a pronounced green or brown tint, which semitransparent stains may not cover.

Choosing the Right Interior Paint

Interior paints come in different gloss ranges, or sheens. In the past, only three were standard: flat, semi-gloss, and gloss. Today, you may be able to choose from up to seven gloss ranges, depending on the manufacturer and the type of paint. Keep in mind that these ranges may vary from one product to another. Some manufacturers get a bit more creative in naming sheens, but the most common are

Flat: This paint is at the low (dull) end of the sheen spectrum. It’s often used on walls and ceilings because it reflects a minimum of light off the surface, reducing glare and helping to hide small surface imperfections. It’s generally not considered washable.

Flat: This paint is at the low (dull) end of the sheen spectrum. It’s often used on walls and ceilings because it reflects a minimum of light off the surface, reducing glare and helping to hide small surface imperfections. It’s generally not considered washable.

Eggshell, lo-luster,

and

satin: These paints have increasing amounts of sheen, making them a little more dirt-resistant than flat paints, and washable. The slight sheen is generally noticeable only when the surface is lighted from the side. It’s a good choice for walls in hallways, children’s bedrooms, playrooms, and other high-traffic areas.

Eggshell, lo-luster,

and

satin: These paints have increasing amounts of sheen, making them a little more dirt-resistant than flat paints, and washable. The slight sheen is generally noticeable only when the surface is lighted from the side. It’s a good choice for walls in hallways, children’s bedrooms, playrooms, and other high-traffic areas.

Semi-gloss: This paint has still more sheen, making it even more washable. Walls in kitchens, bathrooms, mud rooms, and children’s rooms are good candidates for semi-gloss paints. Semi-gloss is perhaps the most widely used latex paint for trim.

Semi-gloss: This paint has still more sheen, making it even more washable. Walls in kitchens, bathrooms, mud rooms, and children’s rooms are good candidates for semi-gloss paints. Semi-gloss is perhaps the most widely used latex paint for trim.

Gloss

and

high-gloss: These paints dry to a durable and shiny surface. High-gloss paint has an almost mirrorlike sheen. Gloss paints are the most dirt-resistant and scrubbable choice for interior trim and most woodwork. Gloss enamels are particularly hard and are an excellent choice for doors, furniture, and cabinets because the surface can withstand heavy cleaning. Some gloss enamels, called deck or floor enamels, are specifically designed for wearing surfaces, such as floors.

Gloss

and

high-gloss: These paints dry to a durable and shiny surface. High-gloss paint has an almost mirrorlike sheen. Gloss paints are the most dirt-resistant and scrubbable choice for interior trim and most woodwork. Gloss enamels are particularly hard and are an excellent choice for doors, furniture, and cabinets because the surface can withstand heavy cleaning. Some gloss enamels, called deck or floor enamels, are specifically designed for wearing surfaces, such as floors.

Finding the Perfect Interior Stain

If you think that variety is the spice of life, you’re going to love shopping for wood stains. Stains are available in a wide variety of wood tones, as well as pastels. Your paint dealer probably has samples so that you can see how various stains look on real wood.

Let your decor and tastes determine which is best for you. For nicely grained wood, such as oak, a penetrating stain that enhances the grain pattern is a good choice. For furniture, cabinets, or moldings made of less attractive wood, or for mismatched pieces of wood, consider using a pigmented stain (a colored “wiping” stain) or a pastel stain; they conceal more.

You can also make your own pigmented stain by thinning alkyd paint with mineral spirits. For example, for a deep black stain, thin flat black alkyd paint with mineral spirits. Start with a 50-50 mix and add mineral spirits, testing often on a scrap of wood until you get just the result you want.

Estimating How Much Paint to Buy

To estimate the amount of paint you need for a project, first consider how much surface area you want to cover. Dust off a math formula that you probably learned in the fourth grade: length (in feet) × width (in feet) = area (in square feet).

The second factor in determining your paint needs is coverage. Virtually all paints and other coatings describe coverage in terms of the number of square feet (area) that 1 gallon covers. The coverage varies by product and is printed on the label. When estimating a smaller project, remember that there are 4 quarts in a gallon and 2 pints in a quart.

The third factor to consider is the condition of the surface. A rough, porous, unpainted surface absorbs much more paint than a primed or topcoated surface. Similarly, a six-panel door requires more paint than a smooth, flat door.

Estimating isn’t an exact science. Keep in mind that you can usually return standard colors, but not custom ones, so it’s more important to be accurate when using custom colors. Although you don’t want to waste paint, a reasonable amount of leftover paint is handy for touch-ups. If you’re like most people who fail to record custom paint colors in a safe place, keeping some extra paint is also the only way to know what color you used when you need to repaint!

Follow this process to figure out how much paint to buy:

1. Find the total area of the surface you want to paint.

For walls, just add together the length of all the walls and multiply the result by the height of the room, measured from the floor to a level ceiling. The number you get equals the total area.

Ceiling measurements are usually fairly straightforward — just multiply the room’s width by its length. Add this number to the area of the walls or leave it separate, depending on whether you’re planning to use different-colored paints for the ceiling and the walls.

If the room has a cathedral ceiling, it has some triangular wall sections (usually two identical ones on opposite walls). Dust off one more math formula: area (of a triangle) = 1/2 base × height. Measure from the top of the wall (usually 8 feet above the floor) to the peak of the triangle. Multiply that number (the height) by 1/2 the width of the wall (the base) to get the square footage of the triangle. If your room has two identical triangles, either double the number or multiply the height by the entire width.

Measuring a home’s exterior is more complex, but the procedure is basically the same. Just break up the surface into rectangles, multiply length by width for each rectangular area, and total them up.

Don’t bother to climb a ladder to measure the height of a triangular gable wall section; count the rows, called courses, of siding from the ground. Measure the exposure (the distance from the bottom of one course of siding to the bottom of the next course) on siding that you can reach easily, and then multiply that number by the number of courses to come up with the height measurement.

2. Account for windows and doors.

To figure how much of the total area is paintable area, you need to deduct for the openings — windows and doors. Unless you have unusually large or small windows or doors, you can allow 20 square feet for each door and 15 square feet for each window. Add up the areas of the openings and subtract that total from the total area.

On the exterior, however, don’t make any deductions unless an opening is larger than 100 square feet. This general rule helps to account for some of the typical exterior conditions described in Step 5.

If you plan to paint the doors, use the following rules. Allow 20 square feet for each door (just the door, not the trim); double that if you’re finishing both sides.

3. Calculate the total area of the trim.

This measurement is a little trickier because widths are usually measured in inches, and lengths are measured in feet. In many cases, you can add up a number of widths and round off the total to feet. For example, take door trim. The 3-inch inside casing + 6-inch jamb + 3-inch outside casing = 12 inches (1 foot) total width. The two sides and the head add up to roughly 17 feet in length. So 1 foot × 17 feet = 17 square feet.

Generally speaking, you can figure about 8 square feet to paint the sash and trim of a standard-sized window.

4. Make a preliminary calculation of gallons required.

Knowing the area to be covered, divide the total square footage of paintable area by the coverage per gallon, which is stated on the label. For example, if you’re painting walls with a paint that covers 350 square feet per gallon, you divide the paintable wall area by 350 to find the number of gallons of paint you need for the walls.

If you get a remainder of less than 0.5, order a couple of quarts to go with the gallons; if the remainder is more than 0.5, order an extra gallon.

5. Factor in surface conditions.

Out go the formulas for this final step. The coverage stated on the label applies under typical (if not ideal) circumstances. A quality latex topcoat applied over a primed or painted, smooth surface, for example, covers about 350 square feet. Just like get-rich-quick schemes or lose-weight-fast diets, though, results will vary. You rarely get as much coverage as the label claims.

Wood shingles and rough-sawn cedar siding require more than the stated coverage, in part because the surface is rough and loaded with joints and cracks. There’s also more area than first meets the eye. On lap or bevel siding (where horizontal boards overlap each other), you must factor in the underside. On a house with board-and-batten siding, you have many edges to paint in addition to the rough faces of the boards. That’s why you don’t deduct for doors and windows on exterior wall calculations.

Similarly, you use more paint if you’re painting interior walls or ceilings that are unfinished, heavily patched, or dark in color. Plan to apply a primer and a topcoat or two. Oddly enough, you may get better coverage with a cheap paint, but the finish won’t be as durable or washable, so pass up bargain paint.

You must make still further allowances for the following conditions:

• Weathered or dry surfaces

• Porous material

• Unprimed, unsealed, or unfinished surfaces

• Rough surfaces

• Molding with a complex or detailed profile

• Cornices or other trims that are assembled by using numerous pieces of lumber or molding

• Raised-panel doors

• Overlapping surfaces

• High contrast between base color and topcoat

Even the type of applicator and your skills can affect the amount of paint you use. A paint sprayer, for example, can waste 10 to 25 percent on surfaces other than the one you’re trying to paint, depending on the type of sprayer and the wind conditions.

If you’re painting problem surfaces, allow 25 to 50 percent extra in most cases. To allow 50 percent more paint, multiply your total painted area by 1.5. To allow 25 percent more paint, multiply the painted area by 1.25. On a large project, like painting or staining an entire house, seek the advice of experienced paint store personnel. If you’re using custom colors, which usually can’t be returned, be conservative and plan a second trip if you need more.

The Workhorses of Painting: Brushes and Rollers

Indoors or out, most painting tasks call for one or more of the big three applicators — brushes, rollers, and pads. (Actually, painting has four workhorses, but the fourth, the paint sprayer, is out in its own pasture. See the section, “Spraying Inside and Out,” later in this chapter.) You can use all three applicators with oil- or water-based finishes, so the surface you plan on painting is the primary determining factor. These applicators produce slightly different textures, which can be a second reason for choosing one type over another.

Brushes

After fingers, the brush is the world’s oldest painting tool. Brushes are made for every application, from the tiniest artist’s brush to super-wide wall brushes. Many brushes are intended for specialized tasks, such as decorative painting techniques.

A good brush gives you the desired result with the least amount of work. Price and feel are the best indicators of quality, and you need to consider the size, texture, and shape of the surface you’re finishing. Keep these points in mind:

Check to see that the ferrule, or the metal band that binds the brush fill to the handle, is made of noncorrosive metal; otherwise, rust may develop and contaminate the finish. The ferrule should be nailed to the handle.

Check to see that the ferrule, or the metal band that binds the brush fill to the handle, is made of noncorrosive metal; otherwise, rust may develop and contaminate the finish. The ferrule should be nailed to the handle.

Be sure the handle is made of unvarnished wood or a nonglossy material. The handle should feel comfortable in your hand.

Be sure the handle is made of unvarnished wood or a nonglossy material. The handle should feel comfortable in your hand.

Brush fill, as the brushing material on a paintbrush is called, is very important and falls into two main categories:

Natural bristle

brushes, sometimes called hog bristle or China brushes (the hogs are from China), are the best, but you can use them only for oil-based paints because the bristles soak up water and get ruined. Hog bristle has a rough texture that picks up and holds a lot of paint, and the ends are naturally split, or flagged. A flagged brush, which looks a bit fuzzy at the tip, allows each individual bristle or filament to hold more paint without dripping and to apply paint more smoothly.

Natural bristle

brushes, sometimes called hog bristle or China brushes (the hogs are from China), are the best, but you can use them only for oil-based paints because the bristles soak up water and get ruined. Hog bristle has a rough texture that picks up and holds a lot of paint, and the ends are naturally split, or flagged. A flagged brush, which looks a bit fuzzy at the tip, allows each individual bristle or filament to hold more paint without dripping and to apply paint more smoothly.

Synthetic brushes are made of nylon, polyester, or a combination of synthetic filaments. Nylon bristles are more abrasion-resistant than natural bristles, hold up to water-based paints, and apply a very smooth finish. Although you can use nylon brushes with oil-based paints, polyester brushes hold up much better to solvents, heat, and moisture and as such are better all-purpose brushes. The best synthetic brushes blend nylon and polyester filaments and are an acceptable compromise for use with exterior oil-based painting.

Synthetic brushes are made of nylon, polyester, or a combination of synthetic filaments. Nylon bristles are more abrasion-resistant than natural bristles, hold up to water-based paints, and apply a very smooth finish. Although you can use nylon brushes with oil-based paints, polyester brushes hold up much better to solvents, heat, and moisture and as such are better all-purpose brushes. The best synthetic brushes blend nylon and polyester filaments and are an acceptable compromise for use with exterior oil-based painting.

After you know what type of brush fill you want, you need to choose the right style. Brush width, the shape of the brush fill (angled or square), and the shape and size of the handle are the most obvious elements. Brush fill quality also varies. As fill qualities are less obvious, some brushes, such as the enamel/ varnish brush and the stain brush, are simply named according to their intended use.

Here are the four standard brush styles:

Enamel (varnish) brushes are generally available from 1 to 3 inches wide. The brush fill is designed to have superior paint-carrying capacity and has a chiseled tip for smooth application. Use these brushes for trim and woodwork.

Enamel (varnish) brushes are generally available from 1 to 3 inches wide. The brush fill is designed to have superior paint-carrying capacity and has a chiseled tip for smooth application. Use these brushes for trim and woodwork.

Sash brushes look like enamel brushes. They, too, are available in 1- to 3-inch widths, but the handle is long and thin for better control. Although laying paint on flat surfaces may be easier with a flat sash brush, an angular sash brush is okay for flat surfaces and is much better for cutting in (carefully painting up to an edge) and getting into corners.

Sash brushes look like enamel brushes. They, too, are available in 1- to 3-inch widths, but the handle is long and thin for better control. Although laying paint on flat surfaces may be easier with a flat sash brush, an angular sash brush is okay for flat surfaces and is much better for cutting in (carefully painting up to an edge) and getting into corners.

Wall brushes are designed for painting large areas, including exterior siding. Select a brush according to the size of the surface you’re painting, but avoid brushes over 4 inches wide. They can get awfully heavy by the end of the day.

Wall brushes are designed for painting large areas, including exterior siding. Select a brush according to the size of the surface you’re painting, but avoid brushes over 4 inches wide. They can get awfully heavy by the end of the day.

Stain brushes are similar to wall brushes, but they’re shorter and designed to control dripping of watery stains.

Stain brushes are similar to wall brushes, but they’re shorter and designed to control dripping of watery stains.

Rollers

A paint roller is great for most large, flat surfaces and is the runaway favorite for painting walls and ceilings. A roller holds a large amount of paint, which saves you time and the effort of bending and dipping. (The only bending and dipping we like to do while painting involves a bag of chips and a bowl of salsa.)

When you buy a roller, choose one made with a heavy wire frame and a comfortable handle that has an open end to accept an extension pole. This isn’t the time to be frugal. Don’t buy economy-grade rollers that tend to flex when you apply pressure and result in an uneven coat of paint. Choose a heavy, stiff roller that doesn’t flex and enables you to apply constant pressure.

A 9-inch roller is the standard size, but you can buy smaller sizes for smaller or hard-to-access surfaces. If you’re painting the town, you can find an 18-inch length.

The soft painting surface of a roller is called a sleeve or cover. It slides off the roller cage for cleaning and storage. Used properly, a quality roller sleeve leaves a nondirectional paint film that looks the same on an upstroke as it does on a downstroke. Clean a sleeve thoroughly after every job, and it’ll last for years.

You can buy two kinds of sleeves:

Natural sleeves, made of lambswool, are preferred for oils because they hold more paint.

Natural sleeves, made of lambswool, are preferred for oils because they hold more paint.

.jpg)

Lambswool shouldn’t be used with water-based paints because the alkali in water-based paints detans the sheep leather and makes it vulnerable to rot.

Synthetic sleeves, usually made of polyester, can be used for both oil- and water-based paints.

Synthetic sleeves, usually made of polyester, can be used for both oil- and water-based paints.

The nap length for the sleeve you choose depends on the type of job you’re undertaking. Check out Table 1-1 for pointers.

| Nap Length | Job | |

|---|---|---|

| 1/4 inch | For very smooth surfaces like flat doors, plastered walls, | |

| and wide trim | ||

| 3/8 or 1/2 inch | For slightly irregular surfaces like drywall and exterior | |

| siding | ||

| 3/4 inch or longer | For semi-rough surfaces like wood shingles | |

| 1 or 1 1/4 inch | For rough surfaces like concrete block and stucco |

Foam painting pads

Painting pads are rectangular or brush-shaped foam applicators, with or without fiber painting surfaces. Some people find them easier to use than brushes. They paint a nice, smooth coat on trim and leave no brush marks, and the larger pads work well on wood shingles. We especially like one that has rollers on the edge to guide the pad when cutting in ceilings and interior trim.

On the downside, pads tend to put paint on too thin. They don’t hold as much paint as rollers or brushes and aren’t as versatile. Using a pad makes it harder to control drips and to apply an even coat on a large surface. Given the time most people need to develop techniques, it may be better to stick with a brush and/or roller for most applications.

Considering Power-Painting Systems

If you plan to do a big painting job, you may want to check out the power-painting systems: power rollers (some include brush and pad accessories) or power brushes. Spray systems are fast, too, and they have several advantages unrelated to speed that make them desirable for many painting and fine finishing projects. (We discuss spray-painting later in this chapter.)

The advantage of power-painting gear is that, after you’re set up and properly adjusted, you can paint like crazy, putting on a lot of paint in record time. If you’re facing a major interior paint job, like when you move into an empty house, or if you plan to paint the exterior of your home with a roller, power rolling is definitely worthwhile. You may also get better results. Most people tend to brush or roll out paint too thin, perhaps to make the most of each time they load the applicator with paint. You’re less inclined to do so with a power-painting system.

Some power rollers have an electric pump that draws paint directly from the can. Others are hand-pumped and use air pressure to push the paint from a reservoir to the roller, where it seeps out of little holes in the roller-sleeve core and saturates the fabric. The techniques for a power roller and a manual one are the same except that you don’t have to reload a power roller. You just roll away and occasionally push a button or pull a trigger to feed more paint to the applicator. Instead of filling a roller tray with paint, you either fill a reservoir or pump directly from the can.

Other than cost, the principal downside of this equipment is the increased setup and cleanup time. You also end up with a fair amount of waste every time you clean. Unlike a brush, roller, or rolling pan that you can scrape to remove most of the paint, you have to wash the paint out of much of this equipment.

Brushing Up on Techniques

Knowing how to use a paintbrush is largely intuitive. Even someone who’s never seen a paintbrush and a can of paint can figure out how to get the desired results, namely to get the paint on the right surface. In this section, we show you a few techniques and tricks that can help you get better results with less fatigue.

It’s all in the wrist

Painting can feel awkward at first, but if you use the techniques we describe in this section, you can look like a pro even if you feel kind of weird.

To hold and load your brush:

1. Hold the brush near the base of the handle with your forefingers just barely extending over the ferrule (the metal band that binds the brush fill to the handle).

For detail work, you probably want to use your good hand, but otherwise swap hands often. Alternating hands takes a little getting used to, but the more you do it, the less fatigued your muscles become and the faster you paint. Changing bodies works well, too.

2. Dip your brush about a third of the way into the paint and tap it (don’t wipe it) on the side of the bucket to shake off excess.

To get the most bang for the buck, fully load your brush. Don’t overload it, but don’t shake off any more paint than necessary to get the brush to the surface without dripping. This brush-loading technique enables you to paint a larger area without having to move your setup.

To lay on an even coat of paint with a paintbrush:

1. Unload the paint from one side of the brush with a long stroke in one direction.

2. At the end of the first stroke, unload the paint from the other side of the brush.

Start in a dry area about a foot away from the first stroke and brush toward the end of the first stroke.

3. Keep the brush moving, varying the pressure of your stroke to adjust the amount of paint being delivered to the surface.

The more pressure you apply, the more paint flows out of the brush, so start with a fairly light touch and gradually increase the pressure as you move along. If you must press hard to spread paint, you’re probably applying it too thin.

4. Brush out the area as needed to spread the paint evenly.

Oil-based paint requires more brushing out than latex, but don’t overwork the finish, especially when using varnish.

Minimize brush marks and bubbles with a finishing stroke — a light stroke, as long as possible, in one direction and feathered at the end. To feather an edge with a brush:

1. Start your brush moving in the air, lightly touch down, and continue the stroke.

2. Slow down near the end of the stroke and, with a slight twisting motion, lift the brush from the surface.

3. Continue in the same fashion in an adjacent area.

4. Immediately brush the paint toward the previous wet feathered edge to blend those two surfaces.

5. Spread and level the paint with additional strokes and feather a new wet edge.

You can’t maintain a wet edge everywhere if you’re painting a large area, so start and finish at corners, edges, or anywhere other than the middle of a surface so that the transition won’t be noticeable. To slow drying, avoid painting in direct sunlight or on very windy days.

Secret weapon: Backbrushing

For some applications, you can take advantage of a roller’s speed, but you should follow up with a brush — a technique called backbrushing. Backbrushing smoothes out roller stipple, pushes out air bubbles, and works the paint into the surface for a better bond. These examples show you when to use this technique.

Rollers leave a slightly stippled paint film that’s fine for walls and siding, but you may not like it on a door or cabinet. A short-fiber pad or wide brush levels the finish on a door or trim nicely.

Rollers leave a slightly stippled paint film that’s fine for walls and siding, but you may not like it on a door or cabinet. A short-fiber pad or wide brush levels the finish on a door or trim nicely.

On exterior surfaces, where a good paint bond to the surface is important, a roller doesn’t do as good a job as a brush. Nothing works paint into a surface quite like a brush. We recommend backbrushing to work spray-applied penetrating and solid-color stains into exterior surfaces.

On exterior surfaces, where a good paint bond to the surface is important, a roller doesn’t do as good a job as a brush. Nothing works paint into a surface quite like a brush. We recommend backbrushing to work spray-applied penetrating and solid-color stains into exterior surfaces.

Backbrush immediately after you apply the finish and while it’s still wet. Dip your brush in the finish just once to condition it, but wipe it against the side of the can to remove the excess. You don’t need to add finish; just work what’s already there.

One final tip: When a project calls for backbrushing, use a team approach — one person with a roller and another with a brush. You’ll fly through the job. Don’t forget to swap tasks on big jobs to avoid the fatigue associated with each task.

May I cut in?

Cutting in describes two quite different painting techniques. In one sense, cutting in refers to the process of carefully painting up to an unpainted edge or an edge of a different color or sheen, such as the joint between trim and siding or between a wall and a ceiling.

Cutting in also refers to using a brush or other applicator to get into corners that a roller or larger applicator can’t get into, such as where the ceiling and wall meet. Accuracy isn’t an issue, so work quickly. Just remember to feather the edges and to paint to the feathered wet edges as soon as possible, especially when applying oil-based paint (see the preceding section).

When cutting in carefully up to an edge, remember that you have the best control if you use an angled sash brush. Use the edge of the brush, not the face, and follow these steps:

1. Lay the paint on close to, but not right on, the edge that you want to cut in.

Keep in mind that more paint is on your brush when you start a stroke, so apply less pressure and/or stay a little farther away at the outset. For the same reason, apply more pressure and move closer to the edge you want to cut in as you lay on the paint with a long stroke or two. Lay on the paint evenly and uniformly close.

2. Start a finishing stroke, varying the pressure to push the paint that you left on the surface in the first pass right up to the edge.

It may take a couple of passes, but with practice, you’ll be able to apply a finishing stroke in one long stroke.

Roller Techniques

The goal — getting paint from the can to the surface — is the same for a roller as for a brush. You just get done faster with a roller. The most important thing to remember is that a roller spreads paint so efficiently and easily that the tendency is to spread it far too thin.

The best way to ensure that you don’t spread the paint too thin is to use a methodical approach:

1. Load a roller fully by dipping it about halfway into your paint reservoir.

Roll the roller very lightly on either the sloped portion of your roller tray or the roller screen, depending on your setup. This technique coats the roller surface more evenly while removing excess that would otherwise drip on the way to the surface.

2. Unload and spread the paint in an area of about 10 square feet.

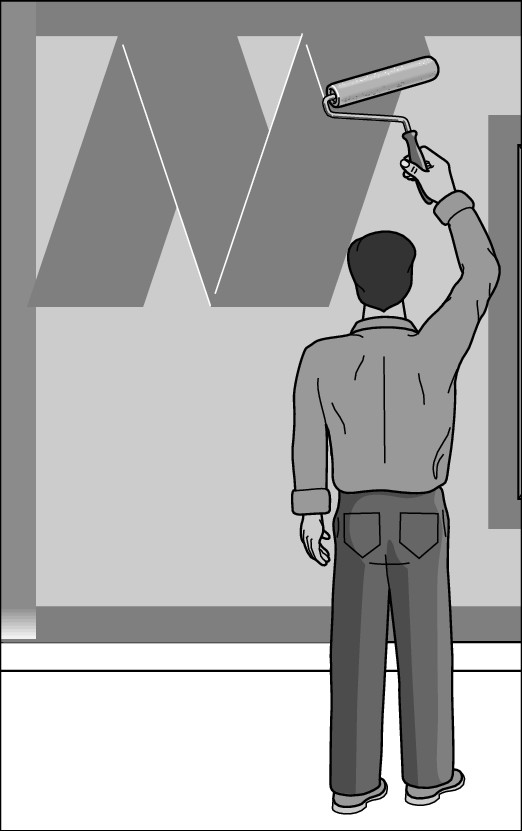

On large surfaces, especially rough ones, unload the paint in an N or other three- or four-leg zigzag pattern; then spread the paint horizontally and make your light finishing strokes vertically. Figure 1-1 shows this three-step zigzag process. Alternatively, you can roll out the paint in one straight line (or two straight lines next to each other), covering about the same area.

3. Reload the roller and unload another pattern that overlaps the just-painted area.

Spread the new paint, blend the two areas, and wind up with finishing strokes.

|

Figure 1-1: Lay on a zigzag pattern, roll it out horizontally, and finish with light vertical strokes. |

|

Normally, you don’t need to feather the wet edge when you’re rolling on paint because you overlap and blend each section before the paint dries. However, a few exceptions exist:

If you’re unable to start or finish an edge at a natural breaking point, such as a corner or the bottom edge of a course of siding, you may need to feather the edge.

If you’re unable to start or finish an edge at a natural breaking point, such as a corner or the bottom edge of a course of siding, you may need to feather the edge.

When you roll paint onto large surfaces where one painted area must sit while you’re working your way back to it, you may have difficulty blending if you don’t feather the edge.

When you roll paint onto large surfaces where one painted area must sit while you’re working your way back to it, you may have difficulty blending if you don’t feather the edge.

Although oil paint takes longer to dry than latex, blending one area with another is harder with oil paint unless you do it almost immediately.

Although oil paint takes longer to dry than latex, blending one area with another is harder with oil paint unless you do it almost immediately.

To roll a feathered edge:

1. Start the motion in the air, lowering the roller to the surface.

2. Roll with light pressure until you near the edge.

3. Gradually reduce pressure and lift the roller off the surface as you pass into the unpainted area.

Indispensable painting accessories

You need more than a brush or roller to paint. You need to accessorize. We’ve found the painting accessories listed here to be particularly helpful.

Swivel/pot hooks: A must for exterior house painting, a pot hook lets you securely hang a paint can or bucket on your ladder, and it swivels to allow you to rotate the can for convenient access.

Swivel/pot hooks: A must for exterior house painting, a pot hook lets you securely hang a paint can or bucket on your ladder, and it swivels to allow you to rotate the can for convenient access.

Extension poles: Spend a couple of bucks for an inexpensive handle extension that screws into the end of a roller handle. You can roll from floor to ceiling without bending and with less exertion, and you avoid constant trips up and down a ladder. Some poles have adjustable heads to which you can attach a paintbrush for hard-to-reach spots or a pole sander for sanding ceilings and walls.

Extension poles: Spend a couple of bucks for an inexpensive handle extension that screws into the end of a roller handle. You can roll from floor to ceiling without bending and with less exertion, and you avoid constant trips up and down a ladder. Some poles have adjustable heads to which you can attach a paintbrush for hard-to-reach spots or a pole sander for sanding ceilings and walls.

5-gallon bucket with roller screen: An alternative to a roller tray is a 5-gallon bucket with a roller screen, a metal grate designed to fit inside the bucket. The rig is ideal for large jobs because it saves you the time you’d spend refilling the paint tray. The bucket is easier to move around and not as easy to step into. At break time, drop the screen in the bucket and snap on the lid.

5-gallon bucket with roller screen: An alternative to a roller tray is a 5-gallon bucket with a roller screen, a metal grate designed to fit inside the bucket. The rig is ideal for large jobs because it saves you the time you’d spend refilling the paint tray. The bucket is easier to move around and not as easy to step into. At break time, drop the screen in the bucket and snap on the lid.

Trim guard: This edging tool is very useful for painting around windows, doors, and floor moldings. Press the metal or plastic blade of the guard against the surface you want to shield from fresh paint. Don’t forget to wipe the edges clean frequently to avoid leaving smears of paint.

Trim guard: This edging tool is very useful for painting around windows, doors, and floor moldings. Press the metal or plastic blade of the guard against the surface you want to shield from fresh paint. Don’t forget to wipe the edges clean frequently to avoid leaving smears of paint.

Aerosol spray-can handle/trigger: This inexpensive handle/trigger snaps onto any aerosol can. The comfort is astonishing, especially if you have a lot to do, but the device’s other value is that it makes it easier to hold the can at the proper angle.

Aerosol spray-can handle/trigger: This inexpensive handle/trigger snaps onto any aerosol can. The comfort is astonishing, especially if you have a lot to do, but the device’s other value is that it makes it easier to hold the can at the proper angle.

Clamp lamp: These inexpensive lamps let you direct light where you need it.

Clamp lamp: These inexpensive lamps let you direct light where you need it.

5-in-1 tool: The Swiss Army knife of painting tools, it can scrape loose paint, score paint lines for trim removal, loosen or tighten a screw, hammer in a popped nail or other protrusion prior to spackling, and scrape paint out of a roller sleeve.

5-in-1 tool: The Swiss Army knife of painting tools, it can scrape loose paint, score paint lines for trim removal, loosen or tighten a screw, hammer in a popped nail or other protrusion prior to spackling, and scrape paint out of a roller sleeve.

Paint mixer: This inexpensive drill attachment does a faster and more effective job than a paint stirring stick. It’s so easy that you’ll actually take the time to stir as often as the instructions say to!

Paint mixer: This inexpensive drill attachment does a faster and more effective job than a paint stirring stick. It’s so easy that you’ll actually take the time to stir as often as the instructions say to!

Spraying Inside and Out

If you love toys — oops, we mean tools — you’re going to love paint sprayers. They apply paint, and more of it, many times faster than brushes, rollers, and power rollers do. They’re also excellent for working on difficult or complex surfaces, such as rough-hewn cedar, concrete, shutters, fences, detailed roof trim, and wicker furniture. Painting or staining exterior siding usually involves applying the same color of paint to large areas, which makes siding a perfect candidate for spray-painting. In this section, we explain what you need to know to choose the right spray equipment, prepare the paint, and use a sprayer safely and effectively.

Keeping an eye on safety

Compressor-driven and airless sprayers atomize paint, which means that the paint breaks up into many tiny particles. These particles float in the air and can be carried for long distances on a breeze, polluting the air that other people breathe and landing on their property. Before you begin, make sure that municipal ordinances permit the use of spray equipment on exterior projects, and never spray on a breezy day or when parked cars or other buildings are nearby.

Personal and environmental risks also vary according to the type of sprayer and tip you use. Of the three types of power sprayers that we recommend for homeowners, only the airless system creates significant overspray. You must take precautions to reduce the risk of overspray, or it becomes a health and/or environmental risk.

.jpg)

Always wear a tight-fitting, organic vapor respirator when spraying solvent-based coatings indoors or outdoors and when spraying water-based coatings indoors. Masks note what they’re safe for — read the packaging to determine whether a mask is appropriate for the job you plan to do. Dust masks don’t offer adequate protection for most spray-painting applications.

Always wear a tight-fitting, organic vapor respirator when spraying solvent-based coatings indoors or outdoors and when spraying water-based coatings indoors. Masks note what they’re safe for — read the packaging to determine whether a mask is appropriate for the job you plan to do. Dust masks don’t offer adequate protection for most spray-painting applications.

Wear splash goggles (preferably a pair with interchangeable lenses), gloves, a hat, and clothing that covers your skin no matter what type of paint you’re using or what the ventilation conditions are.

Wear splash goggles (preferably a pair with interchangeable lenses), gloves, a hat, and clothing that covers your skin no matter what type of paint you’re using or what the ventilation conditions are.

Wear a painter’s hood to cover your head and neck.

Wear a painter’s hood to cover your head and neck.

Apply protective lotion or petroleum jelly to exposed skin.

Apply protective lotion or petroleum jelly to exposed skin.

Never point a sprayer at anyone in jest, and keep your own fingers away from the tip. The pressure of the spray is so great within a few inches of the tip that you may accidentally inject paint deep into your skin.

Never point a sprayer at anyone in jest, and keep your own fingers away from the tip. The pressure of the spray is so great within a few inches of the tip that you may accidentally inject paint deep into your skin.

.jpg)

Never spray flammable products in a hot room or near any source of ignition, such as a spark or standing gas pilot light.

Never spray flammable products in a hot room or near any source of ignition, such as a spark or standing gas pilot light.

Don’t smoke.

Don’t smoke.

Turn off or unplug all sources of ignition, including appliances such as refrigerators, coffee pots, and automatic fans.

Turn off or unplug all sources of ignition, including appliances such as refrigerators, coffee pots, and automatic fans.

Turn lights on or off and put tape over the switches.

Turn lights on or off and put tape over the switches.

Don’t activate any electrical switch until the vapors have cleared.

Don’t activate any electrical switch until the vapors have cleared.

The spray-painting process

You can’t just hook the sprayer up to the paint and start painting. Well, you can, but you won’t like the results. Spray-painting really involves four steps: preparing the work area, preparing the paint, practicing your technique, and, finally, painting the object, all the while adjusting your technique to fit your sprayer.

.jpg)

Prepare the work area

Make sure that the work area is clear and free of tripping hazards or objects that may snag the sprayer hoses.

Make sure that the work area is clear and free of tripping hazards or objects that may snag the sprayer hoses.

Protect nearby surfaces, such as windows, trim, and floors. In most cases, you want to mask off or cover these areas with dropcloths.

Protect nearby surfaces, such as windows, trim, and floors. In most cases, you want to mask off or cover these areas with dropcloths.

Stir and strain the paint or stain

Always stir paint well and then strain it to prevent clogs in the tip or at any internal filters. Clogging is the number-one complaint about spray-painting, but you can prevent nearly all clogs by straining the paint first. Paint suppliers carry a variety of strainers appropriate for different spray equipment. Figure 1-2 shows a typical setup.

|

Figure 1-2: Strain paint before spraying to prevent time-consuming clogs. |

|

Some paints must be thinned for use with most sprayers. Know what your particular situation requires. Paint that’s sprayed on too thick leaves a textured finish that looks like an orange peel, and paint that’s sprayed on too thin doesn’t cover well and tends to sag or run. To be sure that the paint is the right viscosity (thickness), you can buy a viscometer. This small cup has a calibrated hole in the bottom (or a similar device) that you fill with paint and time how long the paint takes to drain out.

Practice basic techniques

Painting practice makes perfect. Sharpen your spraying skills with the following techniques:

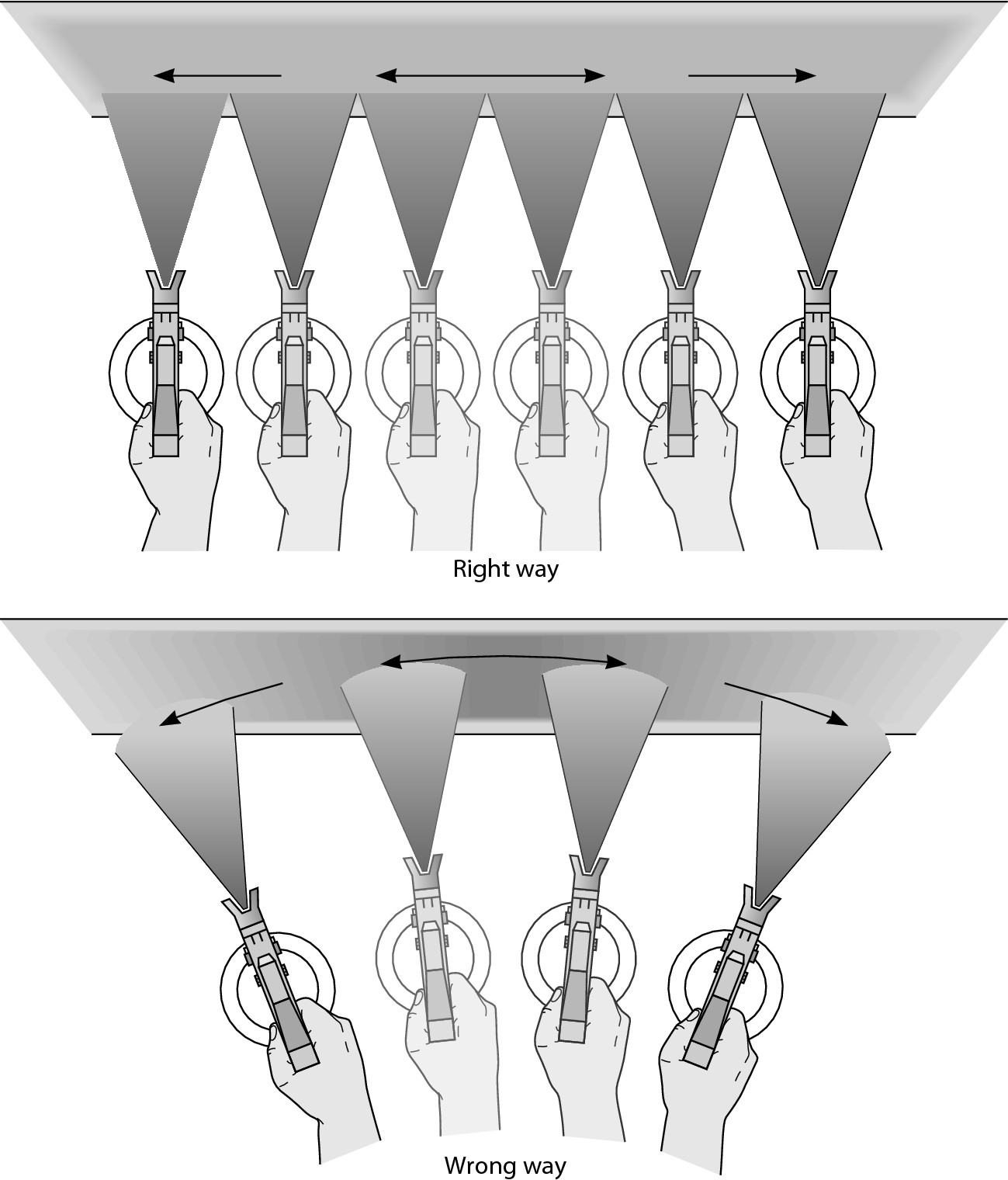

Start moving the gun before you start spraying and keep the gun moving in long, straight strokes. (See Figure 1-3.) Sprayers apply paint quickly, so you must use this technique to get an even coat that doesn’t run. Move as fast as you would brush out a stroke, or 2 to 3 feet per second.

Start moving the gun before you start spraying and keep the gun moving in long, straight strokes. (See Figure 1-3.) Sprayers apply paint quickly, so you must use this technique to get an even coat that doesn’t run. Move as fast as you would brush out a stroke, or 2 to 3 feet per second.

Hold the paint gun nozzle perpendicular to and 10 to 12 inches away from the surface. Even a slight change in this distance significantly affects the amount of paint being applied: If you hold the nozzle twice as close to the surface, you apply four times as much paint. Avoid tilting the sprayer downward or upward, which causes spitting and results in an uneven application.

Hold the paint gun nozzle perpendicular to and 10 to 12 inches away from the surface. Even a slight change in this distance significantly affects the amount of paint being applied: If you hold the nozzle twice as close to the surface, you apply four times as much paint. Avoid tilting the sprayer downward or upward, which causes spitting and results in an uneven application.

.jpg)

Keep the nozzle perpendicular to the surface as you move it back and forth. The natural tendency is to swing the gun in an arc, which results in an uneven “bowtie” application.

Keep the nozzle perpendicular to the surface as you move it back and forth. The natural tendency is to swing the gun in an arc, which results in an uneven “bowtie” application.

Overlap each pass half the width of the spray coverage area to avoid leaving light areas or creating stripes.

Overlap each pass half the width of the spray coverage area to avoid leaving light areas or creating stripes.

Test and adjust the spray equipment until you produce the pattern you want. If the pattern is too narrow, you could apply too much paint to the area, resulting in runs. With a pattern that’s too wide, you have to make more than two passes to get good coverage. A pattern that’s 8 to 12 inches wide is adequate for most large surfaces.

Test and adjust the spray equipment until you produce the pattern you want. If the pattern is too narrow, you could apply too much paint to the area, resulting in runs. With a pattern that’s too wide, you have to make more than two passes to get good coverage. A pattern that’s 8 to 12 inches wide is adequate for most large surfaces.

|

Figure 1-3: Use long, sweeping strokes and maintain a constant distance from the surface. |

|

Start painting

When you’re comfortable and getting the results you want on cardboard, move on to the real thing. Do the corners and any protrusions first and finish up with the large, flat areas. Indoors, for example, paint the two inside corners of one wall and then spray the wall between those two corners before moving on.

Spray corners with a vertical stroke aimed directly at the corner. Move a little quicker than usual, especially on outside corners, to avoid overloading the edges.

After you complete each area, or about every five minutes, stand back and look for light spots or missed areas. Touch up, making sure that you move the gun before spraying. Keep a brush or roller handy for touch-ups.

Most sprayers have a tip guard to protect you from injecting yourself with paint. Remove your finger from the trigger and wipe off the guards occasionally — with a rag, not your finger. Paint buildup at the tip may affect the spray pattern.

Some spray applications require backbrushing or back-rolling — that is, brushing or rolling in the sprayed-on finish to get a more even coat and better penetration. The sprayer, then, is just a fast way to get the paint to the surface. In particular, you should backbrush stain applications on unfinished or previously stained wood. Backbrushing is strongly recommended when applying primers and sealers as well. (Check out the sidebar, “Secret weapon: Backbrushing,” earlier in this chapter.)

The tools of the trade

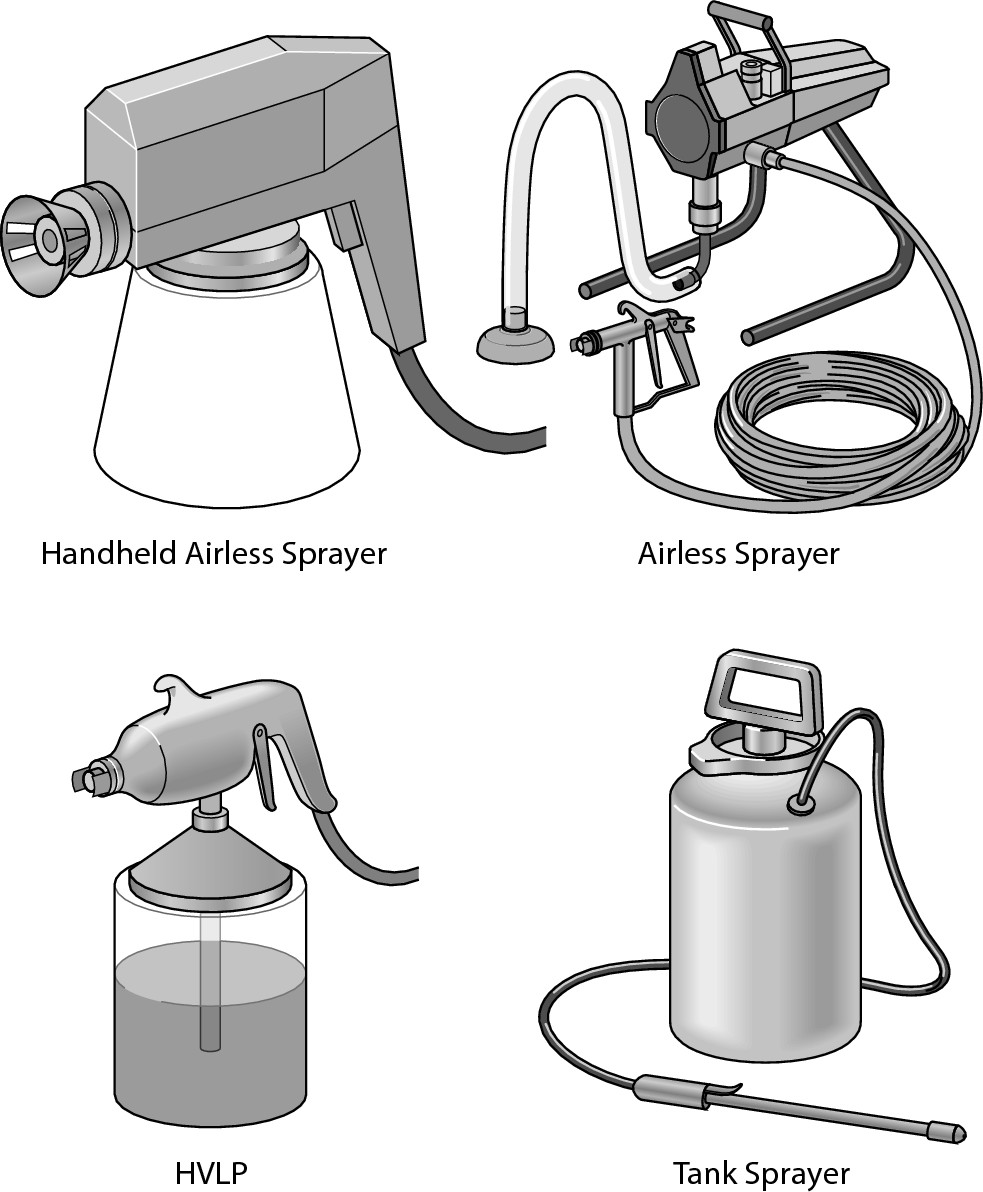

In the power arena, we recommend three types of sprayers for do-it-yourselfers: the tank sprayer, the airless sprayer, and the newer, HVLP (high-volume, low-pressure) sprayer. Figure 1-4 illustrates these types of sprayers. Learning to operate them takes just a few minutes. Conventional sprayers, which are powered by compressed air, require considerably more skill and training. They also create excessive overspray. For these reasons, conventional sprayers are best left to the pros.

Airless sprayers

Handheld airless sprayers won’t win any National Noise Pollution Control awards — they’re noisy little devils — but they’re popular with do-it-yourselfers because of their versatility and moderate price, which ranges from about $50 to $175. The higher-priced units have more power, more features and controls, and more tip options. With a high-powered unit, you can paint everything from a radiator to the entire exterior of your house.

With most models, you draw the paint from a paint cup attached at the base of the sprayer for small projects. On larger projects, you can draw paint from a backpack tank or directly from the can.

Pump airless sprayers are priced from about $250 for do-it-yourself models to as high as $900 for professional models. These sprayers draw paint from 1- or 5-gallon containers to a spray gun through a long hose. Although you can paint a house exterior with a handheld model, a high-productivity pump sprayer is a better choice. These units pump paint much faster, and the gun is much lighter to hold because no cup full of paint is attached to it.

|

Figure 1-4: Good spray-painters for the do-it-yourself painter include a handheld airless sprayer, a pump airless sprayer, an HVLP sprayer, and a tank sprayer. |

|

Operating an airless sprayer isn’t difficult, but you do need a bit of practice to be able to apply an even coat. Here are some tips on using an airless sprayer:

Keep your finger on the trigger, but snap your wrist as you reverse the direction to avoid overloading at the end of each stroke.

Keep your finger on the trigger, but snap your wrist as you reverse the direction to avoid overloading at the end of each stroke.

When using a handheld airless unit drawing paint from a cup, keep one hand on the trigger and the other hand under the cup to support the weight.

When using a handheld airless unit drawing paint from a cup, keep one hand on the trigger and the other hand under the cup to support the weight.

When using a gun, use your second hand to manage the hose, which is sometimes more difficult than handling the spray gun.

When using a gun, use your second hand to manage the hose, which is sometimes more difficult than handling the spray gun.

When buying or renting, ask for a reversible, self-cleaning tip, which flips open to clear a clog without having to be removed.

When buying or renting, ask for a reversible, self-cleaning tip, which flips open to clear a clog without having to be removed.

Tank sprayers

Tank sprayers are available in manual pump and battery-powered models. You can use this multipurpose sprayer to apply oil-based stain to wood decks, fences, and even wood siding. Although you usually need to brush in spray-applied stain (called backbrushing; see the sidebar, “Secret weapon: Backbrushing”), the sprayer does the hard part — getting the otherwise drippy finish onto the surface.

Here are some tips for using tank sprayers:

Never use tank sprayers to spray any liquid thicker than water, which means you shouldn’t use them to spray latex stains, but you can spray oil-based stains.

Never use tank sprayers to spray any liquid thicker than water, which means you shouldn’t use them to spray latex stains, but you can spray oil-based stains.

Adjust any available speed control — faster for large surfaces and slower for greater control when working on smaller surfaces.

Adjust any available speed control — faster for large surfaces and slower for greater control when working on smaller surfaces.

Adjust the spray tip to change the spray pattern — wide for large surfaces and narrow for detail work.

Adjust the spray tip to change the spray pattern — wide for large surfaces and narrow for detail work.

Backbrush as required to smooth drips or work the finish into the surface.

Backbrush as required to smooth drips or work the finish into the surface.

HVLP sprayers

An HVLP sprayer doesn’t atomize paint. Instead, it uses a high volume of air at very low pressure to propel paint onto the surface. As a result, you have virtually no overspray and no risk of explosion. You can produce a very narrow spray pattern, and you don’t need to cover and mask everything in the room or get dressed up like an astronaut — unless, of course, you’re into that sort of thing. Minimum personal protection — splash goggles, protective clothing, and gloves — is usually all that’s required, but use a respirator when using solvent paints or when ventilation is questionable.

HVLP sprayers, priced from $200 to $400 and up, are great for small projects and trim painting, indoors or out. They’re best used with low- to medium- viscosity finishes, such as lacquers, varnishes/enamels, oils, and stains. On models that claim to handle heavier-bodied finishes, such as acrylic latex, you usually must thin the paint. This requirement, combined with the low pressure and relatively small paint cup, makes the HVLP sprayer unsuitable for large projects, such as exterior house painting — unless it’s a doghouse.

Here are some tips on using HVLP sprayers:

Stop spraying momentarily at the end of every pass.

Stop spraying momentarily at the end of every pass.

Control the size of the pattern by moving the gun closer to or farther from the surface and vary the amount of trigger pressure.

Control the size of the pattern by moving the gun closer to or farther from the surface and vary the amount of trigger pressure.

Aerosol paint

Aerosol spraying (with a spray-paint can) is by far the most expensive approach to spray-painting on a per-square-foot basis, but it’s worth every penny on the right job. Aerosol paints dry very fast and are great for small, irregularly shaped objects that are difficult to brush, such as some furniture, iron railings, and exterior light fixtures.

Paint as wide an area as you can reach by using side-to-side strokes, starting closest to you and moving away. As you begin each stroke, point the nozzle to the side of the object you’re painting and start moving toward it. Just before you reach the object, start spraying. Stop spraying as you pass off the other side. Then spray the area again by using top-to-bottom strokes. Several light coats applied this way give uniform coverage without puddling or sagging.

Here are some tips on using aerosol cans:

Before you start painting, shake the can for a full two minutes after you hear the agitator (a little steel ball) rattling in the can. Spray only at room temperature — roughly 65 to 75 degrees. Avoid spraying continuously; use short bursts instead.

Before you start painting, shake the can for a full two minutes after you hear the agitator (a little steel ball) rattling in the can. Spray only at room temperature — roughly 65 to 75 degrees. Avoid spraying continuously; use short bursts instead.

Frequently wipe the tip clean to prevent spitting. When you’ve finished painting, turn the can upside down and spray-paint against a piece of cardboard until only clear propellant comes out. Then remove the tip and soak it in lacquer thinner.

Frequently wipe the tip clean to prevent spitting. When you’ve finished painting, turn the can upside down and spray-paint against a piece of cardboard until only clear propellant comes out. Then remove the tip and soak it in lacquer thinner.

A spray handle tool that snaps onto an aerosol can makes it easier to control and easier on your finger, too.

A spray handle tool that snaps onto an aerosol can makes it easier to control and easier on your finger, too.

.jpg)

Remove the tip from the aerosol can before you attempt to clear a clog.

Remove the tip from the aerosol can before you attempt to clear a clog.

Handy accessories

Quite a few different accessories can help make your painting project a little easier. Here are several that we recommend for spray-painting:

Filters: Set yourself up with a couple of extra paint buckets and paint screens or filters, available at paint outlet stores.

Filters: Set yourself up with a couple of extra paint buckets and paint screens or filters, available at paint outlet stores.

Spouts: With all the pouring back and forth, you’ll find a couple of inexpensive pouring spouts that snap into gallon-can rims and prevent dripping to be quite useful. Cans that have a pouring spout built right in are terrific for this job.

Spouts: With all the pouring back and forth, you’ll find a couple of inexpensive pouring spouts that snap into gallon-can rims and prevent dripping to be quite useful. Cans that have a pouring spout built right in are terrific for this job.

Earplugs: Airless sprayers are noisy, especially indoors. Protect your ears with inexpensive earplugs that conform to your ear canal.

Earplugs: Airless sprayers are noisy, especially indoors. Protect your ears with inexpensive earplugs that conform to your ear canal.

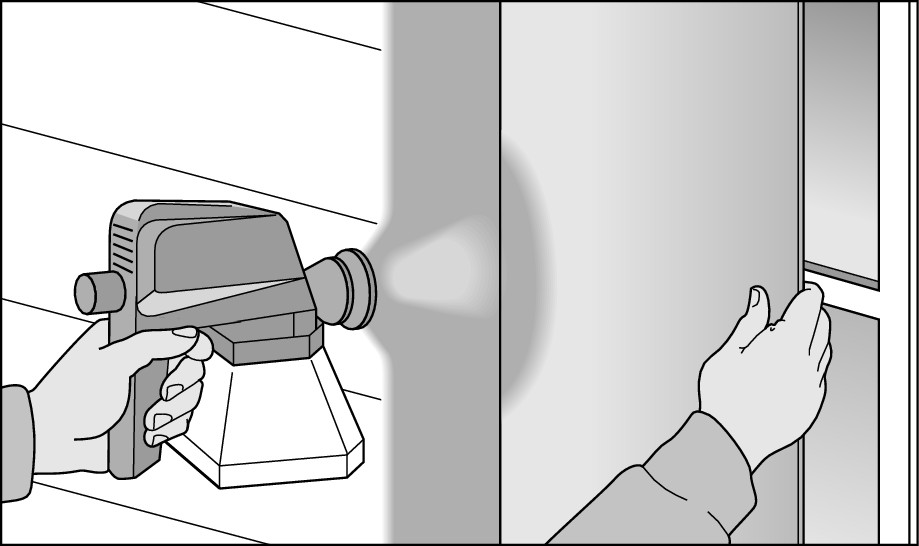

Spray shields: Use a spray shield on virtually every spray job. Pros use aluminum ones with handles. You can buy inexpensive disposable ones made from plastic or cardboard at paint stores (see Figure 1-5). You also can make your own with sheet aluminum, acrylic sheeting, or any other semirigid, lightweight material and a handle fashioned from a piece of wood. Old slats from a Venetian blind work well, too.

Spray shields: Use a spray shield on virtually every spray job. Pros use aluminum ones with handles. You can buy inexpensive disposable ones made from plastic or cardboard at paint stores (see Figure 1-5). You also can make your own with sheet aluminum, acrylic sheeting, or any other semirigid, lightweight material and a handle fashioned from a piece of wood. Old slats from a Venetian blind work well, too.

Spray pole extension: It can get pretty foggy when you’re using an airless sprayer indoors. Use a spray pole extension to move the working end of the tool away from your face. Extensions are available in sizes from 12 inches to 4 feet. By extending your reach, this accessory may also eliminate the need for constant up-and-down movement on a ladder.

Spray pole extension: It can get pretty foggy when you’re using an airless sprayer indoors. Use a spray pole extension to move the working end of the tool away from your face. Extensions are available in sizes from 12 inches to 4 feet. By extending your reach, this accessory may also eliminate the need for constant up-and-down movement on a ladder.

|

Figure 1-5: A large spray shield keeps paint off nearby surfaces. |

|

Should you buy or rent?

Now the money question: Should you buy or rent your spray-painting equipment? Well, it depends.

If you expect to spray-paint only occasionally, consider renting — especially if you’re doing a major interior or exterior job where a good spray unit may save you many hours of work. By renting, you can also step up to a professional-quality unit that applies paint faster and better than a do-it-yourself model that you can afford to buy.

Go where the pros go — to a paint store — to get the right equipment and expert advice on using the equipment. Ask to speak to the person who’s best informed about spray-painting. Describe what you want to paint and what type of finish you’re using so that the employee can recommend the best unit and appropriate spray tips for the job. Get a crash course in how to operate a rental unit and ask for any written material on using or cleaning the equipment. Cleaning is complex and important, so a checklist can come in handy. Also, if you don’t own or want to buy the necessary respirator, rent it.