Chapter 5

Preparing Surfaces for Wallpapering

In This Chapter

Cleaning and setting up the room

Cleaning and setting up the room

Repairing and preparing wall surfaces for wallcoverings

Repairing and preparing wall surfaces for wallcoverings

Removing old wallpaper

Removing old wallpaper

M any of the preparations you need to make before hanging wallpaper are the same steps you take in preparation for interior painting. You want to set up a clear, well-lighted, and safe work area and then take the necessary steps to ensure that surfaces are smooth and in good condition. In most cases, you need to prime and seal the existing wall surface to ensure that the wallpaper adheres properly and that it can later be removed without damaging the wall.

Clearing and Cleaning the Room

To get the room ready for work, remove as much furniture as possible. Ideally, you want a completely empty room, but you can get by with a good 3 feet of work area in front of the walls. In addition, you need a work area where you can set up a table to roll out, measure, and cut wallpaper into strips.

Remove the covers on electrical receptacles and light switches and cover the face of each fixture with masking tape. Also, remove any heating grates or wall-mounted light fixtures.

.jpg)

Next, dust and clean the walls and woodwork. Remove any fuzzy-wuzzies and cobwebs from corners and, if the woodwork is dirty or greasy, wash it with a phosphate-free household cleaner according to the directions. Avoid using cleaners that contain phosphates such as TSP (trisodium phosphate); they’re bad for the environment and leave a residue on walls that prevents primer/sealers from bonding properly.

If you see any mildew, eliminate the source of the problem, such as moisture within a wall or a lack of proper ventilation. Then kill the mildew spores and remove the stain. To do this, use a solution of one part household bleach and three parts water with a little nonphosphate cleaner or detergent. Sponge or spray-mist the stains with the solution and let it sit for at least 15 minutes. Bleach is not good for painted surfaces, so after it has done the deed on the mildew, stop the bleaching action by rinsing well with a neutralizer, such as clean water or a vinegar-and-water solution. Repeat the bleaching and neutralizing processes, if necessary, until the stain is gone.

.jpg)

Remove other stains the best you can and seal any that remain by following the advice in the sidebar “A primer on primers.”

A primer on primers

The key to good wallpaper adhesion is the proper condition of wall surfaces. If you start with a perfectly clean, painted wall, you’re likely to get good results with any prepasted wall-paper. However, you’re guaranteed to get good results if you first apply an acrylic wallpaper primer/sealer to the wall. A primer/sealer not only promotes adhesion but also makes it easier to strip the paper off when you get tired of it or when the next owner prefers another wall finish. Primer/sealer makes it easier to position the wallpaper without stretching it, and that means fewer seams opening up when the paper dries.

If you’re papering over new drywall, applying a coat of primer/sealer is a must. If you don’t start with a primer/sealer, which soaks into and seals the paper surface of the drywall, you’ll never be able to remove the wallpaper without doing serious damage to the drywall. If your walls have ink, lipstick, crayon, nicotine, or other stains on them, seal the stains or they will bleed through both the primer/sealer and the wallpaper itself. For this task, you need an acrylic pigmented stain-killing primer/sealer. However, stain-killers are not wallpapering primer/sealers, so you must follow up with a primer/sealer made for wallcoverings.

Acrylic all-surface wallcovering primer/sealer goes on white but dries clear. Pigmented acrylic all-surface wallcovering primer/sealer is more expensive than the clear stuff, but it helps cover dark or patterned surfaces and helps prevent the color or pattern from showing through the paper. It’s a good idea to tint a primer to the approximate color and shade of the wallpaper background so that the wall color doesn’t show as much if the seams open slightly. Both primers perform equally well on porous and nonporous surfaces.

A coat of wallcovering primer/sealer takes two to four hours to dry, so paint it the day before papering or at least a few hours before you hang the paper. Be sure to read the instructions from the wallcovering and paste manufacturer and consult your wallpaper dealer regarding priming/sealing requirements for your project.

Preparing Wall Surfaces

You can apply wallpaper successfully to a variety of surfaces if you take the necessary steps to prepare the surface. You want smooth walls without any holes, cracks, popped nails, or other bumps that would show through the paper. In addition to following the surface preparation work described in that chapter, you need to be aware of some special preparation considerations for wallpaper.

In most cases, you apply wallpaper over painted drywall or plaster walls or over existing wallpaper on these same surfaces. But occasionally, you may want to apply wallpaper over problem surfaces, such as plywood, metal, prefinished paneling, concrete block, and ceramic tile. If you want to install wallpaper on these surfaces, we suggest that you get detailed instructions from your wallpaper dealer. In some cases, the task calls for hanging a liner paper to level the playing field. In other cases, covering the surface with drywall may be easier.

Smoothing painted walls

To guarantee good wallpaper bond and future removability, coat all painted walls with an acrylic wallpaper primer/sealer (see the sidebar “A primer on primers,” earlier in this chapter). Use 80- to 100-grit sandpaper to machine-sand oil-painted and glossy surfaces before sealing them, but be careful to not sand into the drywall paper covering. If you do, it gets fuzzy. If latex paint comes off when you rub it with a wet cloth, it is of poor quality, and you should use the pigmented variety. You must either machine-sand painted walls until they’re smooth or have them professionally skim-coated with joint compound and then prime them.

Sealing new drywall before papering

New drywall (including patched areas on existing walls) must be well sealed before you hang wallpaper over it. Apply a coat of oil or latex drywall primer/ sealer and then follow up with a pigmented wallpaper primer/sealer (see the sidebar, “A primer on primers,” earlier in this chapter).

Removing Wallpaper

If you want to feel a sense of power, stand in a large room with the world’s ugliest wallpaper and imagine that you can change the destiny of that room. (Dynamite is not an option.) In a perfect world, you could gently pull at a loose seam and the old paper would miraculously peel off the wall, leaving no residue or adhesive — just a nice, clean surface.

In the real world, that scenario is very unlikely. But you don’t have to dread the task of removing wallpaper. Although taking down wallpaper isn’t fun, it’s a good example of grunt work that any do-it-yourselfer can accomplish. The downside is that it’s a messy and time-consuming job.

Knowing what you’re up against

Before you can determine the best approach, you need to know the type of wallcovering and the type of wall surface that’s under the wallpaper. In most cases, walls are either drywall (gypsum sandwiched between layers of paper) or plaster smoothed over lath (either strips of wood or metal mesh). You can usually tell what you have by the feel (plaster is harder, colder, and smoother than drywall) or by tapping on it (drywall sounds hollow, and plaster doesn’t). When in doubt, remove an outlet cover to see the exposed edges.

What about the wallpaper? Be optimistic — assume that the paper is dry-strippable. Lift a corner of the paper from the wall with a putty knife. Grasp the paper with both hands and slowly attempt to peel it back at a very low angle. If it all peels off, you’re home free.

If the wallpaper doesn’t peel off, or if only the decorative surface layer peels off, you must saturate the wallpaper or the remaining backing with water and wallpaper remover solvent and then scrape it off.

Some papers, such as foils or those coated with a vinyl or acrylic finish, are not porous. If you’re removing such wallpapers, you must scratch, perforate, or roughen the entire surface to permit the solution to penetrate below the nonporous surface to the adhesive layer (see “Choosing a removal technique,” later in this chapter). You can test for porosity by spraying a small area with hot water and wallpaper remover. If the paper is porous, you should see the paper absorb the water immediately. After the paper is wetted, you can scrape it off.

Now that you know what you’re dealing with, you can choose an appropriate removal technique for the entire surface. Depending on your situation, choose one of three wallpaper-removal approaches: dry-stripping, wallpaper remover, or steam. Read the how-to for each approach later in this chapter in the section “Choosing a removal technique.”

Preparing for the mess

All wallpaper removal approaches are messy, so take the necessary precautions to protect your floors. For all removals except dry-stripping, we recommend that you lay down a 3-foot-wide waterproof barrier around the perimeter of the room.

You may find pretaped plastic drop cloths, such as adhesive polyethylene sheeting, convenient and reliable. To prevent the watery mess from getting on your floor, tape the plastic to the top edge of the baseboard or, even better, to the wall just above the baseboard, which prevents water from seeping behind the trim. (You can remove the tape when working on the bottom inch of the wall.) Cover the outer 2 feet of plastic with canvas drop cloths or a few old absorbent towels in the area where you’re working. Be careful where you step; the plastic sheeting is slippery.

.jpg)

Gathering tools and supplies for removing wallpaper

You need only a few basic tools and supplies for wallpaper removal. The following list describes the various tools that are available; see the following section for the specific tools you need based on the removal technique you plan to use.

Razor scraper: This push-type wallpaper-scraping tool (about 3 to 4 inches wide) looks like a putty knife but has a slot for replaceable blades so that you always have a sharp edge.

Razor scraper: This push-type wallpaper-scraping tool (about 3 to 4 inches wide) looks like a putty knife but has a slot for replaceable blades so that you always have a sharp edge.

Paper scraper: This nifty gadget can scrape and perforate wallpaper applied on drywall. It has a round, knoblike handle attached to a scraping blade that cuts the paper. Solvents or steam can then penetrate to the adhesive layer but can’t damage the drywall’s paper facing.

Paper scraper: This nifty gadget can scrape and perforate wallpaper applied on drywall. It has a round, knoblike handle attached to a scraping blade that cuts the paper. Solvents or steam can then penetrate to the adhesive layer but can’t damage the drywall’s paper facing.

Wallpaper remover: Although warm water may do the trick (and is certainly priced right), you can turn to commercial wallpaper removal solvents if you need to.

Wallpaper remover: Although warm water may do the trick (and is certainly priced right), you can turn to commercial wallpaper removal solvents if you need to.

Spray bottle or paint roller: Use one or both of these tools to get the water/remover solution onto the wall.

Spray bottle or paint roller: Use one or both of these tools to get the water/remover solution onto the wall.

Wallpaper steamer: Rent one (or buy a do-it-yourself model if you’ve just bought a fixer-upper!) to steam the wallpaper off of your walls.

Wallpaper steamer: Rent one (or buy a do-it-yourself model if you’ve just bought a fixer-upper!) to steam the wallpaper off of your walls.

Plastic and canvas drop cloths: You need both types to adequately protect your floors from the watery mess.

Plastic and canvas drop cloths: You need both types to adequately protect your floors from the watery mess.

Wide masking tape: Tape the plastic drop cloths to the base molding to avoid ruining your floors.

Wide masking tape: Tape the plastic drop cloths to the base molding to avoid ruining your floors.

Water bucket, towels, rags, and wall sponges: After removing the old wallpaper, wash down the walls well.

Water bucket, towels, rags, and wall sponges: After removing the old wallpaper, wash down the walls well.

Choosing a removal technique

The technique you use for removing the old wallpaper depends on what kind of paper you’re taking down and what kind of surface is underneath (refer to “Knowing what you’re up against,” earlier in this chapter). The following sections outline the steps involved in the different approaches.

Dry-stripping

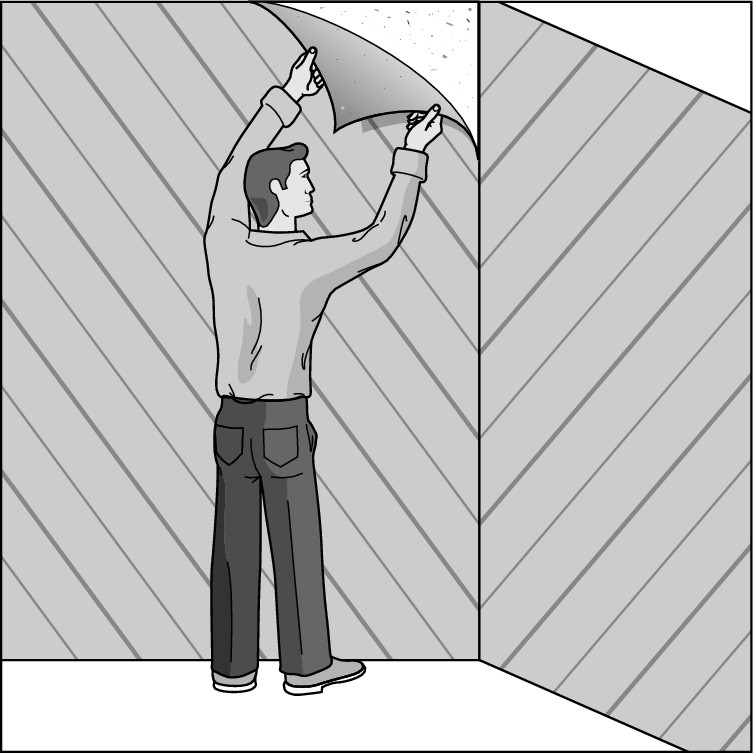

If a wallpaper is dry-strippable, you just need to loosen each strip at the corners with a putty knife and slowly peel it back at a 10- to 15-degree angle, as shown in Figure 5-1.

|

Figure 5-1: Starting from a corner, pull off strip-pable and peelable papers at a very low angle. |

|

.jpg)

After you remove all the paper, follow the adhesive removal procedures the next section describes. If only the top, decorative layer peels off, leaving a paper backing behind, it’s a peelable paper. Dry-strip the entire top layer and then follow the steps in the next section to take off the backing and adhesive.

Soaking and scraping it off

To remove nonstrippable paper or any paper backing that remains after dry-stripping a peelable paper’s decorative layer, turn first to warm water and wallpaper removal solvent. Soak the surface with a wallpaper remover solution. Although a spray bottle works, the most effective way to get the solution on the wall and not all over the floor is to use a paint roller or a spray bottle. Then scrape the sodden paper off with a wide taping knife or a wallpaper scraper.

Scrape off the wet wallpaper and let it fall to the floor. The canvas drop cloth or towels that you put down absorbs most of the dripping solution and keeps your shoe soles a little cleaner.

If the wallpaper is nonporous, you must roughen or perforate the surface so that the remover solution can penetrate and dissolve the adhesive. To roughen the surface, use coarse sandpaper on either a pad sander or a hand-sanding block. You can also use a neat gizmo called a Paper Tiger or another perforating tool devised for use on wallpaper applied over drywall. Rounded edges on these tools help ensure that you don’t cause damage that may require subsequent repair. Don’t use the scraper after the wallpaper is wet, though; you may damage the drywall.

If you’re successful in using the soak-and-scrape approach, skip to the “Winding up” section. If not, it’s time to pull out the big gun: a wallpaper steamer.

Giving it a steam bath

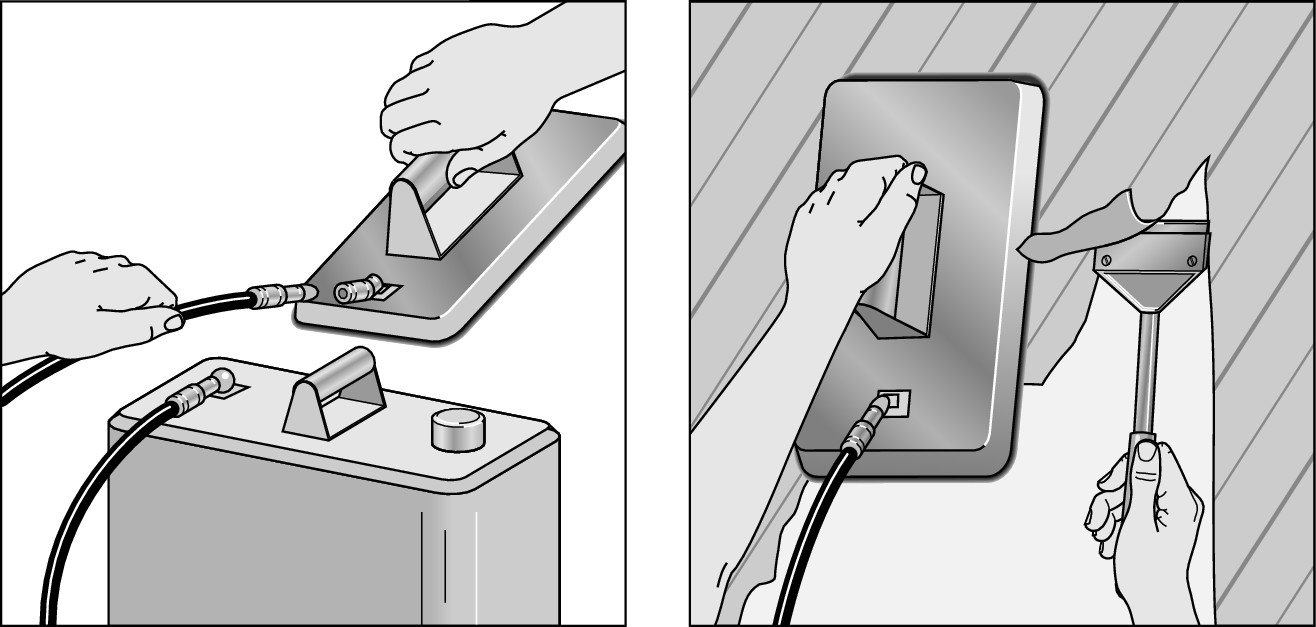

You’re talking major work if you must remove more than one layer of wall-paper or remove wallpaper that has been painted over. And if the wallpaper was not applied to a properly sealed surface, removing it without damaging the wall can be next to impossible. For these tough jobs, you may have to rent a wallpaper steamer (about $15 for a half-day) or buy a do-it-yourself model (about $50). A wallpaper steamer is a hotplate attached to a hose extending from a hot water reservoir that heats the water and directs steam to the hotplate, as shown in Figure 5-2.

|

Figure 5-2: Use a wallpaper steamer to steam and scrape away old paper. |

|

.jpg)

Before you start steaming, prepare the room (refer to “Preparing for the mess” earlier in this chapter) to protect the floor. Fill the steamer with water and let it heat up.

Starting at the top of the wall, hold the hotplate against the wall in one area until the wallpaper softens. Move the hotplate to an adjacent area as you scrape the softened wallpaper with a wallpaper razor scraper and let it fall onto the plastic as described in the preceding section. When you’re through scraping one area, the steamer usually has softened the next area, depending on the porosity of the paper.

.jpg)

Winding up

After you remove all the wallpaper and any backing, the walls are usually still quite a mess, with bits of backing and adhesive residue still clinging to them. Wash off any remaining adhesive residue with remover solution or with a nonphosphate cleaner in water, using a large sponge or sponge mop. You can use an abrasive pad or steel wool on plaster, but use caution on drywall. Avoid overwetting or abrading the paper facing.

Rinse your sponge often in a separate bucket of water, squeeze it out, and rewet it in the removal or cleaning solution. Continue washing this way until the walls are clean.

When the walls are completely dry, make any necessary repairs and do surface preparation work as we describe in the section “Preparing Wall Surfaces,” earlier in this chapter.