Chapter 3

Installing Countertops and Sinks

In This Chapter

Getting your tools together

Getting your tools together

Attaching a post-formed countertop

Attaching a post-formed countertop

Installing a sink and faucet

Installing a sink and faucet

Installing tile

Installing tile

A new countertop can add a finishing touch to a total kitchen remodel or stand alone as an upgrade that makes an outdated kitchen look like a million bucks. A new countertop doesn’t cost that much, either. Stock countertops cost as little as $3 to $4 per linear foot. Even custom-made and ceramic tile countertops and backsplashes aren’t that expensive — at least when compared to the cost of remodeling an entire kitchen.

A moderately skilled DIYer can handle the installation of a post-formed countertop, which is a seamless piece of laminate with a particleboard substrate (base) that covers the entire backsplash, flat surface, and front edge. A ceramic tile countertop isn’t too far beyond the skill level of most average to experienced DIYers, either, if you take your time and have some patience. However, leave installing solid-surface, granite, and concrete countertops to a pro.

The main focus of this chapter is on installing a post-formed countertop. We also show the basic steps for installing a ceramic tile countertop and backsplash. We don’t get into every possible problem or situation, but we do give you a solid primer on what to expect and where to go for assistance if you decide that installing a tile countertop is a project you want to tackle.

Gathering the Right Tools

We can’t stress enough how much easier you make your task by getting all the tools together for the entire project before you start. Set up a pair of sawhorses and a half sheet (4 x 4 feet) of plywood to act as a staging area for tools. With that setup, you have all the tools laid out so that they’re easy to grab when you need them. A well-laid-out staging area also makes your helper’s job easier if you send him off to get tools.

Here are the tools you need for installing countertops:

1/2-inch open-end wrench

1/2-inch open-end wrench

3/8-inch corded or cordless drill

3/8-inch corded or cordless drill

3/4-inch spade bit

3/4-inch spade bit

3/4-inch thick wood strip for support behind the laminate end cap

3/4-inch thick wood strip for support behind the laminate end cap

Belt sander (an 18-, 21-, or 24-inch model)

Belt sander (an 18-, 21-, or 24-inch model)

Carpenter’s wood glue or liquid hide glue

Carpenter’s wood glue or liquid hide glue

C-clamps

C-clamps

Clothes iron (for applying end caps to post-formed countertops)

Clothes iron (for applying end caps to post-formed countertops)

Compass (Check your kid’s geometry gear before you run out and buy one!)

Compass (Check your kid’s geometry gear before you run out and buy one!)

Drywall screws (1-, 1 1/4- and 1 1/2-inch)

Drywall screws (1-, 1 1/4- and 1 1/2-inch)

End-cap kit (for finishing ends)

End-cap kit (for finishing ends)

Fine-tooth steel plywood blade

Fine-tooth steel plywood blade

Hand file

Hand file

Heavy-duty extension cord

Heavy-duty extension cord

Heavy-duty work gloves and eye protection

Heavy-duty work gloves and eye protection

Household iron

Household iron

Levels (both 2-foot and 4-foot)

Levels (both 2-foot and 4-foot)

Masking tape

Masking tape

Package of wood shims

Package of wood shims

Phillips screwdrivers (medium-sized, straight-tip, and No. 2)

Phillips screwdrivers (medium-sized, straight-tip, and No. 2)

Portable circular saw

Portable circular saw

Powered jigsaw

Powered jigsaw

Pressure sticks (short lengths of 1 x 1 or 1 x 2 board or trim)

Pressure sticks (short lengths of 1 x 1 or 1 x 2 board or trim)

Rags or cardboard (to protect your countertop’s surface when you use squeeze clamps)

Rags or cardboard (to protect your countertop’s surface when you use squeeze clamps)

Sanding belts, sized for your belt sander (coarse, 60 grit; medium, 100 grit)

Sanding belts, sized for your belt sander (coarse, 60 grit; medium, 100 grit)

Sawhorses (two)

Sawhorses (two)

Scrap 1 x 4 board of short length (a 4-footer works)

Scrap 1 x 4 board of short length (a 4-footer works)

Squeeze clamps (at least one pair)

Squeeze clamps (at least one pair)

Tube of construction adhesive

Tube of construction adhesive

Tube of silicone caulk and a caulk gun

Tube of silicone caulk and a caulk gun

Utility knife

Utility knife

Installing a Countertop

Post-formed countertops are great for DIYers because the laminating step is eliminated and the mitered corners are precut. Stock countertops are available in 2-foot increments, so to complete an installation you have a bit of work ahead of you. First, you need to scribe it to fit against any end wall and then cut it to length; if it turns a corner, you’ll join the precut 45-degree mitered ends. After you’ve installed the countertop, you follow up the installation by cutting out a hole for your sink (if your countertop wasn’t already precut for a sink — certainly enough sawing and drilling to give you that DIYer’s high!

Ensuring a perfect fit: Scribing and trimming

Wouldn’t it be great if your walls were as straight and true as the edges of the countertop? Well, we haven’t seen a house in all our years of experience where this is the case.

1. Start in a 90-degree corner, measure out 3 feet, and mark that spot.

2. From the same corner, measure out 4 feet in the opposite direction and mark that spot.

3. Using a tape rule, measure the distance from the end marks of the 3- and 4-foot marks.

If the walls are square, the distance between the marks will be 5 feet.

To shape the edges of your countertop, you need to transfer the contour of the wall onto the countertop’s edge surface. Use a compass to scribe, or transfer, the wall’s contour onto the laminate.

1. Set the countertop in place where you plan to install it.

When installing any section of countertop, check that it’s level. Use a 2- or 4-foot level. If the countertop isn’t level, slide shims between the countertop and the support struts of the cabinet frame to level the countertop. The shims will remain in place and won’t move after you secure the countertop to the cabinets.

2. Set your compass to fit the tip in the widest gap between the countertop and the wall.

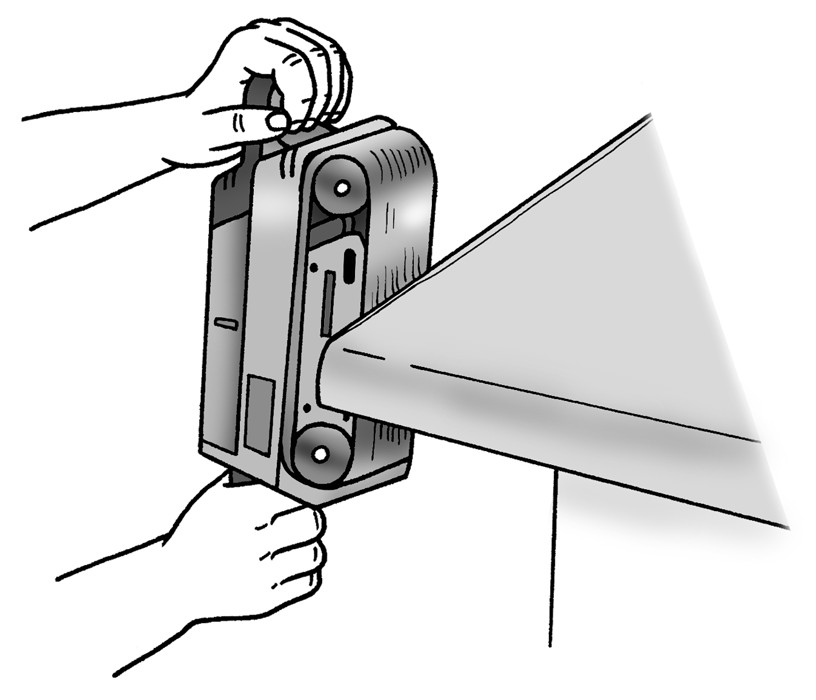

3. Move the compass along the wall to draw a pencil line on the countertop’s surface that matches the wall contour (see Figure 3-1).

Do so for both the backsplash and for any edge that’s against a wall.

|

Figure 3-1: Scribe a line on the countertop surface. |

|

4. Remove the countertop and set it on a pair of sawhorses.

5. Secure the countertop to the sawhorses with squeeze clamps.

Place a rag or piece of cardboard between the clamp jaws and the countertop’s surface to protect the surface.

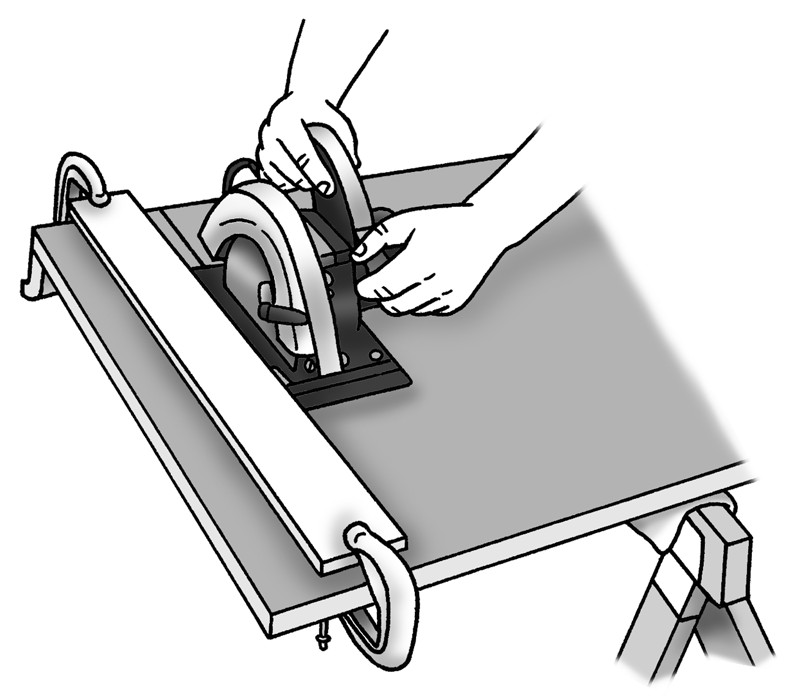

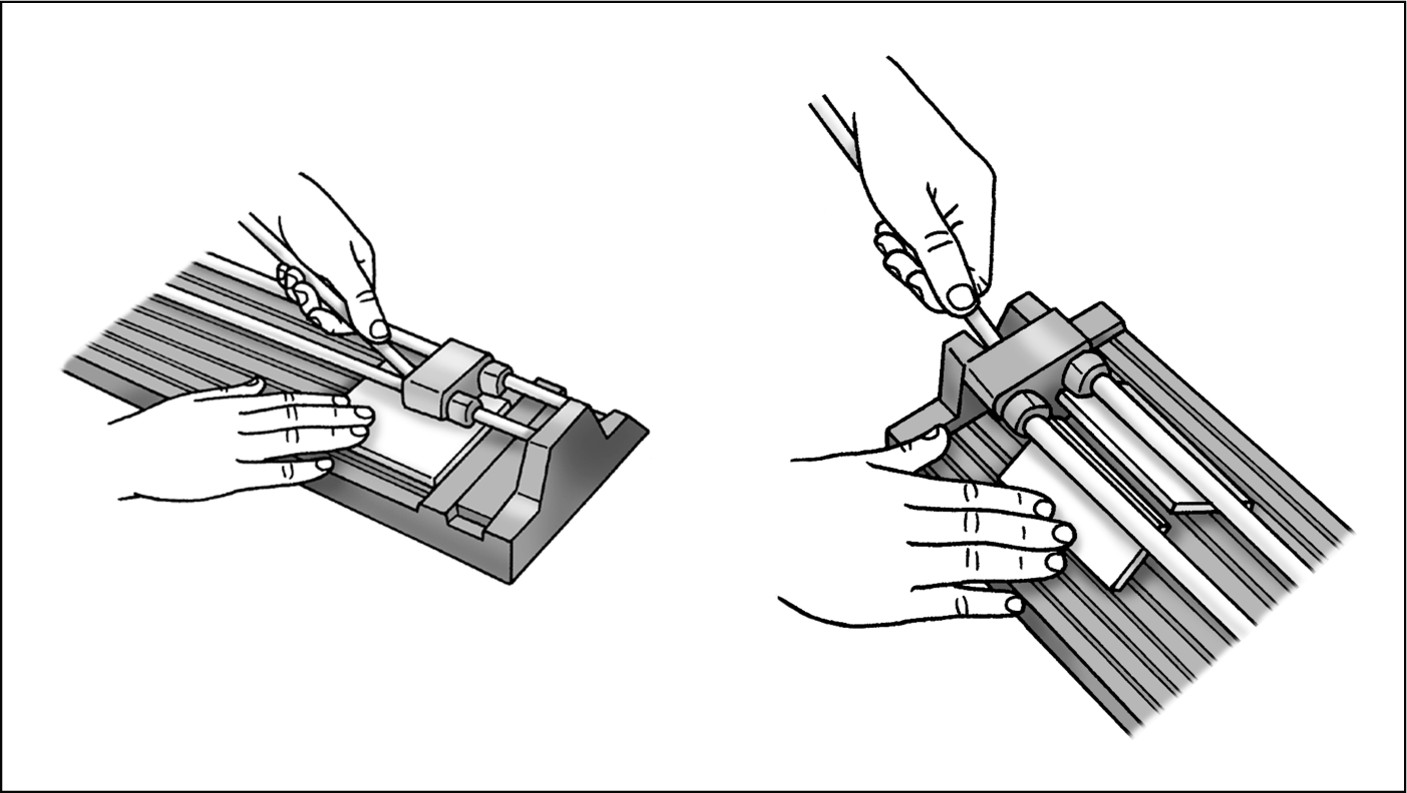

6. Remove the excess countertop (up to the pencil line) with a belt sander and a coarse (60-grit) sanding belt (see Figure 3-2).

A coarse belt works best because it removes laminate and the substrate quickly yet neatly. If you have a lot of excess countertop, say 1/8 inch or more, cut off most of it with a jigsaw and then use a belt sander to finish up to the pencil line.

Hold the sander as shown in Figure 3-2. Avoid an upward cut, which might chip or lift the plastic laminate.

|

Figure 3-2: Sand off excess laminate and substrate up to the scribed line. |

|

7. Reposition the countertop and check for any tight spots.

8. Touch up any tight spots with the sander and recheck the fit again before cutting it to length (as described in the following section).

You want the countertop to fit, especially if you’re installing it during the humid summer months when the wall is fatter with humidity. If you’re installing the countertop in the drier winter months, leave a gap of about 1/16 inch along the wall to allow for movement due to changes in temperature and humidity. Fill the gap with a bead of silicone caulk as one of the final steps in the remodel.

Sizing and finishing your countertop

Stock countertops are sold in 2-foot increments, so most folks have excess to cut off. Because most situations call for cutting, post-formed countertops are generally manufactured without end caps, which you need to apply.

Cutting off excess

The easiest way to cut off any extra length of a post-formed countertop is with a circular saw and fine-tooth steel plywood blade. Don’t use a carbide-tipped blade — those blades have larger teeth, which increase your chances of chipping the laminate. Just follow these steps:

1. Place the countertop upside down on a pair of 2 x 4s on sawhorses.

Be sure to extend the 2 x 4s under the entire countertop so that the cutoff is fully supported. You may want to clamp the countertop to the sawhorses for extra security; however, the weight of the countertop should be enough to keep it from moving.

2. Measure the length of countertop that you need and mark a cutting line on the substrate.

3. Cut and clamp scraps of 1 x 4 to the backsplash and to the underside of the counter to guide your cuts (see Figure 3-3).

The distance between the guide and the cut line varies according to the saw and blade that you use. Measure the distance from the edge of the saw shoe (base) to the inside edge of the blade to determine proper spacing.

|

Figure 3-3: Cut the countertop along your cutting guide. |

|

4. Make your vertical cut through the backsplash first and then cut from the rear of the countertop toward the front.

.jpg)

Support the cutoff end or have a helper hold it while you cut. Failure to do so will cause the piece to fall away before it’s completely cut and will break the laminate unevenly, ruining the countertop. If you have trouble finishing the cut with the circular saw, stop about 1 inch from the end and finish with a jigsaw or handsaw.

Applying end caps

If your countertop has an exposed end that doesn’t butt against a wall or into a corner, you need to finish it by applying a laminate end cap — a piece of the laminate surface that covers the exposed end of the countertop substrate.

1. Attach the provided wood strips to the bottom and back edges of the countertop with wood glue and brads, which the kit may also provide.

These strips support the end cap because the substrate alone isn’t thick enough. Make sure that the strips are flush with the outer edge.

2. Position the end cap on the cut end of the countertop and align the angle and corner with the contour of the countertop’s surface.

3. Maintain that alignment as you run a hot clothes iron over the end cap to activate the adhesive.

4. After the glue and end cap have cooled, finish the edges.

File off excess material that extends past the backing strips. Also, lightly file the top edge so it isn’t quite as sharp. A hand file works best. Push the file simultaneously toward the countertop and along its length.

.jpg)

Never remove excess by pulling the file — always push! Pulling breaks the glue bond, and the end cap will come off and may even break.

5. Reinstall the cabinet doors, put the drawers back in place, and you’re set.

Installing a mitered corner

If your countertop turns a corner, it probably has two pieces, each with a 45-degree angle, or miter cut. These cuts meet to form the 90-degree corner. Chances are good that you have to do some scribing and trimming of the backsplash to get it to fit against the wall without leaving gaps and to make the front edges of the two pieces meet without any of the substrate showing. Follow these steps:

1. Place the countertop pieces in the corner to assess the fit.

Align the two pieces so the mitered edges meet properly. Push the counters against the wall and into the corner as far as possible without misaligning them. At the same time, adjust them until the overhang at the cabinet face is exactly the same along the entire length of both tops.

2. Scribe and trim the back edges of each piece (as described in the “Ensuring a Perfect Fit: Scribing and Trimming” section) so that the rear mitered points fit exactly in the corner of the wall.

Typically, excess joint compound in the corners requires you to trim some material from this area. Additional trimming may be required to compensate for other wall irregularities.

3. Before you join the pieces, mark the ends where you need to cut them to length (as described in the preceding section).

4. After cutting the tops to length and applying the laminate ends, apply yellow carpenter’s glue or liquid hide glue to both edges of the mitered joint and reposition the two sections.

Either glue works well; however, carpenter’s glue sets up more quickly. If you use it, you need to work faster.

5. Connect the two pieces from the underside with the toggle bolts that came with the countertop.

Position the wings of the bolt into the slots on each piece. Tighten the bolt with an open-end wrench. As you do so, check the joint on the surface to make sure that the seam is perfectly flush. If it isn’t, adjust the countertop position and retighten the toggle bolts.

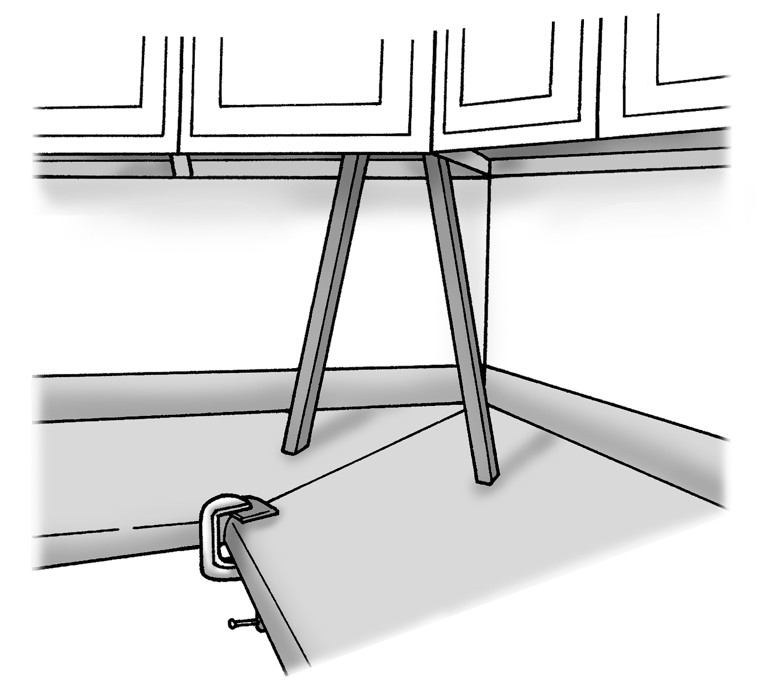

6. To ensure that the joint stays flush while it dries, place a C-clamp on the front edge joint and place pressure sticks on either side of the joint, as shown in Figure 3-4.

Pressure sticks are simply two equal lengths of board (usually 1 square inch in thickness) that are slightly longer than the distance between the countertop and the bottom of the wall cabinets. They need to be longer than that distance so you can wedge them in place to force pressure onto the countertop.

|

Figure 3-4: Create a smooth seam with pressure sticks. |

|

Cutting a hole for the sink

You can order your countertops pre-cut, including a hole for the sink, but do so only if you know that all your measurements are absolutely, positively dead-on, with no chance of being off by even a little bit. And if you’re like us, that’s very unlikely. Cutting a hole in a post-formed countertop isn’t difficult. Just follow these steps and take your time for professional-looking results.

Using a template

Most sinks come with a paper or cardboard template to help outline the area you’re going to cut out. Quite often, the cardboard template is part of the shipping box for the sink. Use a utility knife to cut the template from the box. Just be careful not to cut yourself, and be sure to follow the line so that the template is as straight as possible.

1. Lay the sink upside down on the countertop where you’re going to install it.

2. Measure from the back edge of the sink to the backsplash to make sure that the sink is evenly positioned.

Make sure that the sink is back far enough — typically very close to the backsplash — so that when you install the sink, it will fit behind the cabinets with room for the mounting clips.

3. Trace around the outer edge of the sink with a pencil.

Have a helper hold the sink in place or tape it to ensure that it doesn’t shift while you’re tracing.

4. Measure the lip on the underside of the sink.

5. Mark the dimension of the lip in from the line you traced around the sink.

Mark it on the counter at several points inside the traced line and then draw straight lines connecting the marks. You can freehand the corners — just follow the same shape as the corners you traced by using the sink.

The distance between the two lines forms the lip on the countertop to support your sink. The inner line is the cutting line.

Making the sink cutout

To cut a hole for a sink, we always use a jigsaw, which allows for great control. ( Note: Always, always, always use a new jigsaw blade. An old or dull blade can chip the laminate along the cutting line.) Some people use a circular saw; however, doing so involves making a plunge-cut with the blade because you don’t have a starter hole to work with. Most folks find that a jigsaw is the easiest, most reliable, and safest saw to use. Wear heavy gloves and eye protection when making this cut.

1. Drill two starter holes in opposite corners just inside the cutting line. Use a 3/4-inch spade bit and drill through the laminate and substrate.

Don’t worry if the cut edge is rough. The rim of the sink will cover it. You’re cutting into sections that you’ll eventually cut out and toss (in the garbage; not just up in the air).

2. Place the blade of the jigsaw in the starter hole and line up the blade exactly on the cutting line (see Figure 3-5).

3. Cut slowly along the line.

Don’t be in a rush — let the saw do the work. Again, don’t worry about any little chips that may occur. The sink lip will cover them.

|

Figure 3-5: Insert the jigsaw blade in the starter hole and cut around the entire inner (or cutting) line. |

|

When it’s time to install the sink and faucet, move on to the “Installing a Sink and Faucet” section for all the information you need. You’ll find it easier to drill for and even install the faucet before you attach the countertop.

Attaching countertops other than corners

After you’ve scribed, trimmed, test fit and applied any end caps to the countertops and the glue has set at any mitered corners, you can begin the job of securing them to the base cabinets.

.jpg)

Follow these steps to attach a countertop to the base cabinets:

1. Position the countertop pieces on the cabinets.

2. Apply a bead of silicone caulk or construction adhesive along the top edge of all the cabinet parts that support the countertop.

Tip up a straight countertop to apply the adhesive. Insert shims under a mitered countertop rather than trying to tip it up — doing so is easier and is less likely to break the glue joint. The caulk or adhesive will hold all the parts in place after it dries.

3. Lower the countertop back into place or remove the shims.

4. Place pressure sticks every 12 to 18 inches to help the adhesive bond the countertop to the cabinets at the back edge and apply clamps to the front edge.

Be sure to place pressure sticks along the back corners (where the corner blocks are located) to get the countertop down tight.

5. Seal any gap between the backsplash and the wall or along the edges and the wall with a clear silicone acrylic caulk.

6. Reinstall the cabinet doors, put the drawers back in place, and go have another beer.

.jpg)

Installing a Sink and Faucet

Installing a sink and faucet in your kitchen is easy whether you’re doing a complete kitchen remodel or simply upgrading the look of your kitchen. The information in this chapter, coupled with the manufacturer’s instructions for both the sink and the faucet, will help you through the steps.

Gathering the right tools

The fewer trips you make to get tools and materials, the less time you waste and the faster you finish your project. Here are the tools you need to gather for installing your sink and faucet:

Groove-joint pliers

Groove-joint pliers

Adjustable wrench

Adjustable wrench

No. 2 Phillips screwdriver

No. 2 Phillips screwdriver

Medium-sized slotted (straight tip) screwdriver

Medium-sized slotted (straight tip) screwdriver

Caulk gun

Caulk gun

A tube of silicone caulk/adhesive

A tube of silicone caulk/adhesive

A small container of plumber’s putty

A small container of plumber’s putty

Spud wrench

Spud wrench

Bucket and rags

Bucket and rags

Of these tools, the spud wrench is the one you are least likely to own, but it’s one that will make the job easier. The spud wrench is engineered to fit the locknut that is used to secure the sink basket to the sink. A spud wrench costs under $10 and is available wherever plumbing tools are sold.

Setting the stage: Preparing to install your sink

Much of the work of sink installation actually takes place before you set the sink into the countertop. Taking your time with the preliminary work ensures a smooth installation.

.jpg)

Taking the measurements

In most cases, the old plumbing configuration will work with your new sink. But if you’re making a major change in the design of the new sink, be sure that the old plumbing fits the new sink’s requirements. So, before you buy or order a sink, take a few measurements.

Establishing the drain height

Make sure to measure the distance from the underside of the countertop to the center of the drain line that comes out of the wall. This distance is usually between 16 and 18 inches, which allows adequate space for the water to drop into the trap and still leaves enough space below the trap for storing items underneath the sink in the cabinet.

The drain height is usually not an issue unless you’re going from a very shallow sink to one that has very deep bowls (9 to 12 inches deep). Even if you do switch to deeper bowls, it may only be a problem if your old setup had a shallow bowl coupled with a high drain exit position. This may sound like a less than likely setup but it does happen.

Determining the shut-off valve heights

You should also measure the height of the shut-off valves. Measure from the floor of the sink base cabinet to the center of the valve.

Remember, though, that houses built before roughly 1980 were not required to have shut-offs on every sink supply line, so you may not have any at all. If your sink doesn’t have shut-off valves, install them now while you’re working on the system. If your kitchen didn’t have shut-offs when you tore out the old sink and faucet and you’ve been working on the sink installation for a few days, you better have installed individual shut-off valves by now or your family won’t be speaking with you. Where there are no shut-off valves and there are open pipes or lines, the only way to keep the water from running out is to shut down the entire water supply. Not a good idea when your daughter is getting ready for a big date.

Making sure to attach the faucet before installing the sink

Yes, the heading is correct. The easiest and best way to install a faucet is before the sink is in place. If you install the faucet before installing the sink, you won’t have to strain or reach because everything is completely open.

Getting to know your sink

Most sinks come with factory-drilled holes along the back edge or lip. The number of holes should be equivalent to the number of holes needed for your faucet, so pay close attention when buying your faucet and sink. If you have a single-lever faucet, you’ll want a single- or two-hole sink, depending on if your faucet needs a separate sprayer hose hole or if you want a soap dispenser on the sink.

Many sink and faucet combinations use four holes. In most cases, the first three holes from the left (as you face the front of the sink) are for the faucet. The hole furthest to the right is for a spray hose, separate water dispenser tap, or soap dispenser. Some newer sink designs have the holes positioned so that the dispenser hole is the one on the left, but this would be clearly marked on the carton or explained in the instructions. The first hole from the left and the third hole from the left are spaced 8-inches-on-center, which is commonly shown as 8-inches o.c.

Securing the faucet to the sink

Well, it’s time to begin the assembly process.

1. Place the faucet over the three holes on the left with the faucet’s water supply tailpieces (threaded pieces located directly beneath the faucet handles) going into the two outside holes.

2. Screw the plastic nuts onto the threaded tailpieces (which will later connect to the supply lines) and hand-tighten until snug.

3. Use groove-joint pliers to finish tightening the nuts.

Be careful not to over tighten the nuts. Plastic nuts are easy to strip or ruin with pliers.

4. Seal the area where the faucet meets the sink, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Some faucets come with a rubber gasket that goes on the bottom of the faucet body between it and the sink. Other faucet manufacturers recommend applying a bead of silicone tub-and-tile caulk on the bottom of the faucet body before positioning the faucet on the sink. Both methods keep water from getting underneath the faucet where it could run down the factory-drilled holes and drip onto the sink base cabinet floor.

.jpg)

Attaching water supply lines to the faucet

After the faucet is secured to the sink, you can attach the water supply lines that will eventually be connected to the shut-off valves on the main water supply pipes. Regardless of what your supply line is made of, it probably uses a coupling nut to secure it to the faucet tailpiece. Simply screw the coupling nut onto the tailpiece until it’s snug and then give it a couple of final snugs with groove-joint pliers.

.jpg)

Dealing with factory-attached tubes

Some faucets come with factory-attached soft-copper supply lines on both the hot- and cold-water tailpieces, which means the only attaching will be directly to the shut-off valves. You should, however, do a little preshaping of the soft-copper before setting the sink into position in the countertop.

Measure the distance between the water supplies under the sink and then gently bend the soft-copper supply tubes until they’re about the same distance apart as the water supply. They don’t have to be exact, just close.

.jpg)

Installing flexible copper supply tubes

Flexible copper supply tubes are similar to, if not the same as, the factory-attached soft-copper supply tubes found on some faucets. The same care is needed to bend and shape the copper tubes that you install. Try to shape the tube into position before attaching it to the sink’s tailpieces. After the tube has been shaped, secure it to the tailpiece with the coupling nut.

1. Position the tube between the tailpiece and the shut-off valve and mark the tube so that it will fit down into the valve after it has been cut.

2. Use a tubing cutter to cut off the excess.

3. Attach the tube to the tailpiece with a coupling nut and use the compression nut and ring to secure the other end of the tube to the shut-off valve.

Installing the newest tubes — Braided!

One of the best new plumbing products to come along is the line of braided steel supply lines. They’re constructed of a rubber supply (like a hose) wrapped in a steel-braided outer jacket. And what’s really great about them is their flexibility. You can take the excess length and simply put a loop in it and then connect it to the shut-off valve.

.jpg)

After you’ve attached the supply tubes, attach the spray hose if you have one. Slide the coupling nut end of the hose through the mounting ring and hole in the sink. The sprayer head rests in the mounting ring when not in use. Attach the coupling nut on the sprayer hose to the threaded outlet on the underside of the faucet, usually located under the center of the faucet body.

Other sink extras, such as a soap dispenser or hot water spigot, should be installed now. Follow the manufacturer’s installation instructions.

Putting things in position: Finishing your installation

Now that the plumbing supply stuff is in place, it’s finally time to put the sink in place and see how it looks. After the sink is in place, you can make the supply line and drain line connections that will transform the gaping hole in your countertop into a working sink.

Setting in your sink

.jpg)

1. First, dry-fit the sink to determine exactly the right spot.

Set the sink into the opening in the countertop. Remember to use the basket holes to grip the sink, not the faucet. Center the sink in the opening and then draw a light pencil line on both sides and along the front edge of the sink.

2. Lift out the sink and flip it over.

You don’t need to take the sink back to your shop to do this, either. Lay a piece of cardboard on the countertop to protect it (and the sink) from scratching and then flip the sink over so that the faucet handles and neck hang over the edge of the countertop.

3. Apply a bead of silicone caulk (about 1/4-inch wide) around the edge.

The caulk prevents water from getting between the sink and the counter, and it also holds the sink in place. Use a silicone-based tub-and-tile caulk, which usually contain mildew killers and stand up against the dirt, soap scum, and crud that you’re sure to find around the kitchen sink. Silicone caulks also remain somewhat flexible, which is helpful because the sink will actually drop very slightly when it’s filled with water and then lift when the water is drained. The movement is very slight, but over time this movement would cause a regular latex-based caulk to crack.

After the caulk has been applied, you need to keep the installation moving so the caulk doesn’t dry before you get the sink in place.

4. Lower the sink into position using the pencil lines to get it in the same location.

5. Let the sink rest for about 30 to 45 minutes before you install the sink baskets so that the caulk has time to set up or cure.

Installing the sink baskets

After the caulk has cured, install the sink baskets (the stainless steel catcher/ strainers we mentioned earlier).

1. Start by applying a 1/4-inch thick rope of plumber’s putty around the entire underside lip of the basket.

The putty seals the gap between the lip and the groove of the sink basket hole. Don’t put the putty on the groove — it’s too easy for it to get shifted out of position and then the basket will leak.

2. Now fit the baskets into the holes in the sink bowls and secure them to the sink using the rubber washer, cardboard gasket, and metal locknut that are supplied with the basket.

Make sure you install the rubber washer first, the cardboard gasket second, and the locknut last. If you don’t, water will leak under the basket lip.

3. After you’ve hand-tightened the locknut, use the spud wrench to finish securing the locknuts.

4. Finally, remove the excess putty that is forced out between the sink basket and the sink and beneath the sink.

.jpg)

Connecting the supply lines

No matter what type of material you use for your water supply lines, you want leak-free connections. The fastest connection to use is the screw-on nut and washer that’s on the ends of a steel-braided supply line. Simply tighten the nut onto the threaded outlet on the faucet tailpiece and the shut-off valve and you’re set to go.

Another commonly used type of connection is called a compression fitting. It consists of a coupling nut, which secures the fitting to the faucet tailpiece and the shut-off valve, and a brass compression ring, which forms the sealed connection between the supply line and the fitting it’s attached to. Compression fittings are a tighter connection than a screw-on nut and washer fitting. Here’s how to properly install a compression fitting:

1. Start by sliding the compression nut onto the supply line with the nut threads facing the valve.

2. Now slide the compression ring onto the supply line.

3. Place the end of the supply tube into the appropriate valve, making sure that it fits squarely in the valve opening.

If the supply line end doesn’t go in straight, the connection will leak, because the angle of the end of the supply line won’t allow the compression ring to sit or “seat” properly between the supply line and the valve fitting.

4. Reshape the tube until it fits squarely.

5. Once the tube is in place, pull the compression ring and nut onto the valve and screw it tight.

6. Open the shut-off valve to check the connection for leaks.

Keep some rags handy, just in case.

Hooking up the drain line

Drain kits come in different materials and configurations, but installing them is a snap. Choose the kit with the configuration for your sink type, and you’re halfway home!

Choosing the right kit

You have a couple of choices for drain kits: chromed metal kits and PVC drain kits. Both work well and are about equally easy to use. The main factor on deciding which one to use is cosmetic — will the drain line be visible? If it will be visible, you’ll want to use the chromed kit. If it’s out of sight in the sink base cabinet, which most kitchen drains are, then the good-old white plastic PVC kit is the way to go; PVC is cheaper.

Kitchen sink drain kits, whether they’re chromed or PVC, use nut and washer screw-together connections. Besides being easy to install, they also let you easily disconnect the assembly when it’s time to unclog a drain or quickly rescue that wedding ring that fell down the drain. A basic, single-bowl kit includes

A tailpiece, which connects to the bottom of the sink strainer

A tailpiece, which connects to the bottom of the sink strainer

A trap bend (or P-trap), which forms a water-filled block to prevent sewer gas from coming up through the sink drain

A trap bend (or P-trap), which forms a water-filled block to prevent sewer gas from coming up through the sink drain

A trap arm, which is connected to the downstream end of the P-trap and then to the drain line that leads to the main drainage line

A trap arm, which is connected to the downstream end of the P-trap and then to the drain line that leads to the main drainage line

A double-bowl drain kit will have everything the single-bowl kit has along with a waste-Tee connection and additional length of drain line to connect both bowls to a single P-trap.

If your sink is a triple-bowl, you need a third set of pieces for the third bowl. Individual traps, bends, tailpieces, and pipe sections, as well as slip nuts and washers, are sold separately, so finding the extra pieces is no problem. Availability of individual parts is also especially nice for occasions when, for example, you accidentally cut off too much of the tailpiece and it doesn’t reach the connecting waste-Tee. (Gee, does it sound like we may have some personal experience here?)

.jpg)

Making the connection

Assembling and connecting the drain kit is fairly simple.

The great thing about drain line kits is that the pieces are really quite easy to move and maneuver, so you can adjust them to fit almost any setup. Don’t expect the horizontal pieces to be in super-straight alignment with the tailpieces or the drainpipe. The only thing that matters is that they all eventually get connected together. Take a look at your old sink drain setup and you’ll see what we mean.

1. Start by attaching the tailpiece to the sink drain and tightening the slip nut and washer by hand.

If you have a multiple bowl sink, all of the drain tailpieces should be the same length for an easier installation.

2. Next, slip the trap onto the tailpiece and then position the trap’s horizontal piece next to the drain line coming out of the wall.

The horizontal piece must fit inside the end of the drain line. Remove the trap and cut the horizontal section to fit.

3. Reattach the trap to the tailpiece and into the drain line and tighten the slip nuts and washers.

Checking for leaks (Put on your raincoat first)

Before you do anything else, get the bucket and rags ready. Lay some rags directly below each connection so that, if there is a leak, the towels will immediately soak up the water. And leave the rags there for a couple of days, just in case a leak develops over time.

Have your helper turn on the water while you begin inspecting for leaks. Don’t open up the shut-off valve just yet. Let the water pressure build up to the shut-off valve so that there’s time for any slow-leak drips to occur. Leaving the valves closed for a few minutes should be long enough to know whether any water is leaking. Once you know the shut-off valve connection isn’t leaking, open the valve so that the water goes into the supply lines. Again, let the water pressure build in the supply lines for a few minutes and then inspect the supply connections at the faucet tailpieces.

Don’t be alarmed (or upset) if you have a joint that leaks. We’ve done a lot of plumbing projects and we still get the occasional leaky joint. Just shut off the water, take a deep breath, disassemble and reassemble the connection, and check again for leaks. No sense crying over spilled milk — or, in this case, a drippy plumbing joint.

Installing a Ceramic Tile Countertop

Another type of countertop that is quite popular and is a manageable DIY project for most homeowners is ceramic tile. Ceramic tile is not only attractive, but also very durable and resistant to spills and stains. Tile is available in a wide range of colors, sizes, and styles. A ceramic tile countertop is more expensive than a post-formed top and involves considerably more work, but the beauty of ceramic tile is usually enough to offset the extra cost and labor.

Gathering additional tools for tile

In addition to the tools listed at the beginning of this chapter, here’s what you need to install a tile countertop:

3/4-inch AC-grade plywood

3/4-inch AC-grade plywood

1 x 2 board (used for front edge build-up)

1 x 2 board (used for front edge build-up)

Framing square

Framing square

Grout and grout sealer

Grout and grout sealer

Latex underlayment filler

Latex underlayment filler

Notched trowel

Notched trowel

Plastic tile spacers

Plastic tile spacers

Rubber grout float

Rubber grout float

Tile adhesive (mastic) or thinset

Tile adhesive (mastic) or thinset

Tile backer board

Tile backer board

Tile cutter (available at rental stores)

Tile cutter (available at rental stores)

Tile nipper (special pliers used for cutting/nipping small pieces)

Tile nipper (special pliers used for cutting/nipping small pieces)

Tiles, straight and bull-nose (or countertop edge trim)

Tiles, straight and bull-nose (or countertop edge trim)

Constructing your ceramic countertop

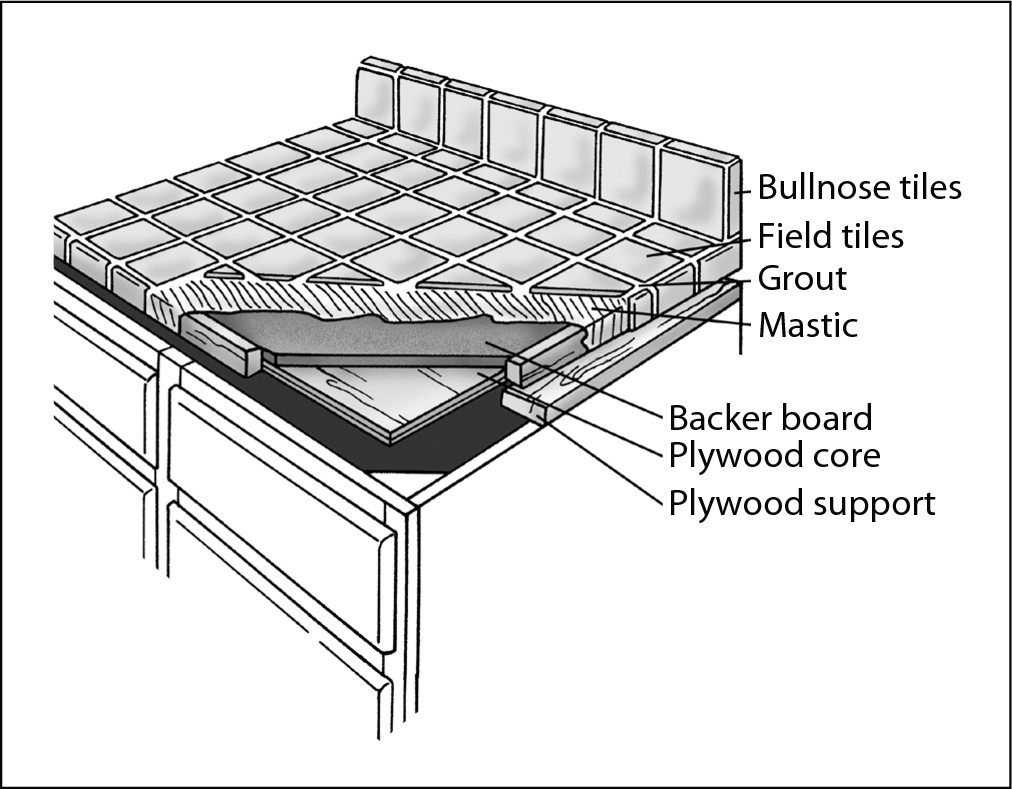

A ceramic tile countertop is made up of 3/4-inch exterior plywood and tile backer board (a cement or special gypsum panel) cut to the same size as the tops of the cabinets. You then edge the edges of the plywood and backer board sandwich with 1 x 2 strips of wood. You apply the tiles directly to the backer board and secure them with mastic or thinset mortar. Finally, you fill the gaps between the tiles with grout; you must seal these gaps to prevent moisture from getting under the tiles and loosening them.

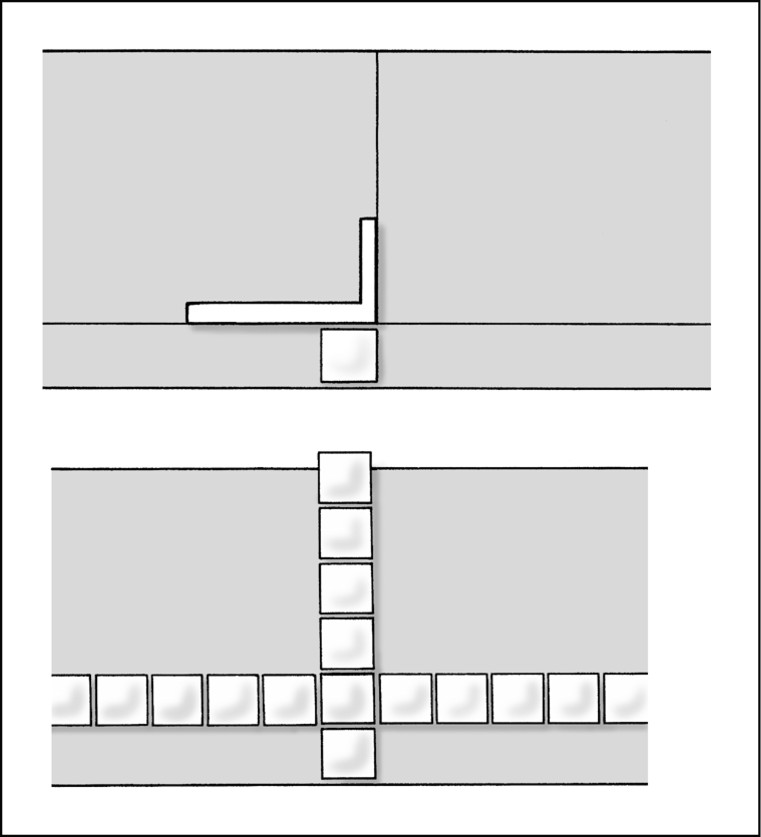

You need two styles of tile for a countertop: straight-edged, or field tiles, and bull-nose tiles. Bull-nose tiles come in two styles: a single rounded edge for use along a straight edge, and a double bull-nose (two adjacent rounded edges) for use on outside corners. Alternatively, you can use countertop edge trim tiles instead of bull-nose tiles. Using a wet saw, you must cut them to length and miter them to fit inside and outside corners. (Your tile dealer can usually make wet-saw cuts for you.) The backsplash on a ceramic tile top can be installed over a separate particleboard core (backerboard isn’t needed) or directly on the wall. The top of the backsplash can end with a bull-nose tile or extend to the underside of wall cabinets. Figure 3-6 shows how a ceramic tile countertop fits together.

|

Figure 3-6: The many layers of a ceramic tile countertop. |

|

Here’s a quick look at the basic steps for building a ceramic tile countertop:

1. Cut and position the plywood core so it fits against the wall flush with the face of the cabinets. Secure it to the cabinets with drywall screws.

Drill pilot holes through the plywood into the top edges of the cabinets. Measure carefully and pencil a line to guide (center) pilot hole placement. Lift the top to apply construction adhesive, and replace it to drive the screws.

2. Cut tile backer board, such as cement board, and test its fit.

To cut cement board, score the surface with a utility knife guided by a metal or wood straightedge; snap to break in along the scored line; and complete the cut of the reinforcing material with your utility knife.

3. Attach the backer board cement board screws or exterior-rated drywall screws, as suggested by the manufacturer.

For a more rigid installation, use a notched trowel to apply mastic or thinset mortar (available where tile is sold) over the plywood before attaching the backer board.

4. Apply self-adhering fiberglass mesh tape over any joints and fill in the screw-head holes with a latex underlayment filler or thinset.

Allow the filler to dry and then sand it smooth.

5. Attach a 1 x 2 board to the front edge, making sure it’s flush with the top of the backer board.

Nail and glue the board to the plywood with 4d finishing nails.

6. Determine the position of the first course and draw a line parallel to the front of the countertop to indicate where the back edge of the tiles will align.

Position bull-nose tile (or countertop edge trim tile) on the front edge and a field tile on the top separated by a tile spacer. Add more spacers on the back edge and place a board against it. Then trace a line along the board to mark the edge of the first course of field tiles.

7. Measure the length of the countertop and mark the centerline perpendicular to the line you just drew, as shown in Figure 3-7.

Align one leg of the square with the line and the other with the mark you made to indicate the centerline.

8. Dry-fit rows of tile along the lines using tile spacers, as shown in Figure 3-7.

On a straight counter, determine whether it’s best to center a tile on the centerline or align an edge with it. Choose whichever leaves you with the widest tile at the ends. If you have a countertop that turns a corner, lay out the tiles starting at the corner. On a countertop that wraps two corners, lay out tiles starting at the corners and plan the last (cut) tile to fall in the center of the sink.

|

Figure 3-7: Dry-fit rows of tile along the lines. Mark any tiles that need to be trimmed. |

|

9. Use a tile cutter to make straight cuts on field and bull-nose tiles (see Figure 3-8). If you have a countertop edge trim, have your supplier cut it with a wet saw after all tiles are in place.

|

Figure 3-8: Use a tile cutter to score and cut the tiles to fit. |

|

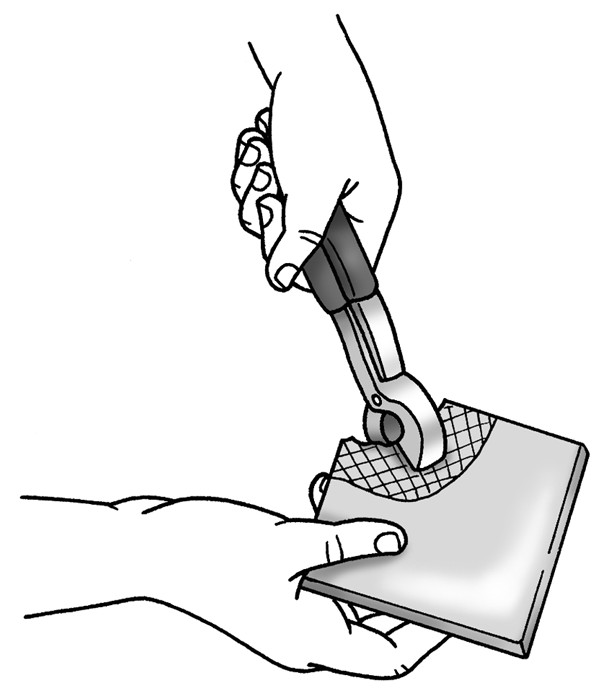

10. To make curved cuts, freehand score the area on the tile to be removed with a glass cutter. Then use a tile nipper to break off numerous small pieces until the cutout is complete (see Figure 3-9).

|

Figure 3-9: Remove small pieces of tile with a tile nipper. |

|

11. After you’ve dry-fit and cut all the tiles, secure them to the substrate with mastic or thinset mortar, as advised by your tile supplier.

Apply the mastic or thinset with a notched trowel to ensure a uniform coat and use plastic tile spacers between tiles to ensure even spacing. Allow the mastic or thinset to set up for at least 24 hours.

12. Fill the gaps between the tiles with grout by using a rubber grout float.

Hold the float at a 45-degree angle to the tiles and use a sweeping motion to force grout into the gaps. Wipe off any excess grout with a damp sponge. Let the grout dry for about an hour and then wipe off any haze on the tile. Don’t let grout on the tile dry too long or you’ll never get it off! After you clean the surface, allow the grout to dry per the instructions on the package.

13. Seal the grout with a penetrating silicone grout sealer.

Although sealing the grout seems like a tedious job (and it is!), it’s critical that you do it to keep the grout from staining and to extend its useful life.