Chapter 6

Rub a Dub Dub! Replacing a Tub

In This Chapter

Choosing and installing a new bathtub

Choosing and installing a new bathtub

Removing the old tub

Removing the old tub

Sprucing up an old tub that can’t be removed

Sprucing up an old tub that can’t be removed

T his is where remodeling a bathroom gets personal. Are you a tub person or a shower person — or both? Shrinks probably have theories about what people’s personal bathing preferences disclose about their personalities, but we’d rather leave that one alone. We do know that most people have definite preferences. If you’re a tub person who delights in soaking in bubbles or steaming in hot bathwater, you have a lot of options. Even if your space is limited or odd shaped, you can probably find a bathtub or whirlpool tub to fit your space and satisfy your desire for bathing luxury.

What if you have an old bathtub that can’t be removed? Sure, with a sledgehammer anything’s possible, but we discuss when it makes sense to leave an old tub in place, give it a cover-up, and improve the room around it.

Selecting a Bathtub

Want to soak and simmer in hot, steamy water? How about easing your aches and pains with a soothing massage? Or maybe you’re an in-and-out kind of bather who wants nothing more than hot water and plenty of it. Do some noodling about what you like and don’t like about your current tub and make a list of your preferences. After you nail down your bathing priorities, you’re in for a whole lot of choices. Options range from posh platform tubs to charming replica claw-foot tubs.

The typical bathtub is 5 feet long, 14 inches deep, and 32 inches wide, but there are variations on this theme. Longer, deeper tubs are available to accommodate different shapes and sizes of bathers. Many 6- and 7-foot tubs are sized for two bathers. Square or corner tubs range from 4 feet square and larger. Most tubs are configured with either a left- or right-hand outlet for the drain to accommodate different installations.

Bathtub manufacturers offer a rainbow of colorful shades, many of them coordinated with matching sinks and toilets. Whites and neutral shades are the least expensive and easiest to get. For resale purposes, real estate agents say that subtle neutrals are the best choice. But if your heart is set on taking a bubble bath in a navy blue bathtub, go for it.

Bathtubs are made from a variety of materials. Your budget will likely determine which material you choose:

Cast iron: A cast-iron tub is the most expensive option. The heaviest material, cast iron offers deep, rich colors and a glossy surface that can’t be matched. It’s the best you can buy.

Cast iron: A cast-iron tub is the most expensive option. The heaviest material, cast iron offers deep, rich colors and a glossy surface that can’t be matched. It’s the best you can buy.

Steel: Formed steel coated with enamel is a popular material for tubs. It’s lighter than cast iron but not as durable.

Steel: Formed steel coated with enamel is a popular material for tubs. It’s lighter than cast iron but not as durable.

Acrylic: Acrylic tubs are molded and shaped in any number of configurations and feature a durable easy-care surface.

Acrylic: Acrylic tubs are molded and shaped in any number of configurations and feature a durable easy-care surface.

Fiberglass: These lightweight tubs are easy to handle and are an economical alternative to acrylic.

Fiberglass: These lightweight tubs are easy to handle and are an economical alternative to acrylic.

Bidding Good Riddance to an Old Tub

Anyone who has remodeled a bathroom will tell you that the most difficult part of the project is removing the old tub. You have to remove all the plumbing fixtures, disconnect the plumbing lines — that’s the easy part — and then dislodge, cajole, and finally lift out the monster. The finale involves manhandling the tub (in one piece or many pieces) out of the bathroom, through the house, and to the trash. Everyone should experience this act of skill and brute force. The sense of relief is sheer bliss.

Built-in, platform, and footed tubs offer unique challenges. An old built-in may have layers of wallboard, tile, or surround material holding the tub in place, so removing the walls is the first job. (See the section “Taking out the tub,” later in this chapter, for those instructions.) That old charmer of a platform or footed tub is heavier than an elephant and just about as easy to move down a staircase. Sometimes the only way to get it out is to bust it up with a sledgehammer and remove it in pieces.

After the old tub is gone, the bathroom will appear to have grown in size, and you’ll probably discover (if you haven’t already) the key to unlocking the inner workings of your bathroom’s plumbing.

Gaining access to the plumbing

First, a word about working on the plumbing lines of a bathtub. If you’re lucky, your bathtub plumbing lines are accessible through an access panel, a removable inspection panel that’s often located in a hall or the closet of an adjoining room. The panel is a piece of plywood that’s framed in and fastened by screws that probably have been painted over. If you have one of these inspection panels, working on the tub, faucet, and valve will be much easier, and you won’t disturb the walls around the tub.

1. On the wall, mark off a 30-inch rectangle of wallboard that gives you full access to the tub’s pipes and fittings.

Use a carpenter’s level to mark off the rectangular outline so that the horizontal and vertical lines are square.

2. Use a drywall saw to cut the wallboard, following the outline to make the opening.

3. Make the panel by cutting a piece of 1/4-inch plywood a couple inches larger than the opening and sanding the edges.

4. Secure the corners of the panel with wood cleats or screws.

5. Paint your new access panel to match the wall.

Disconnecting the plumbing lines

All tubs connect to the plumbing lines in the same way. Turn off your water supply and then follow these steps to disconnect your lines:

1. Standing in the tub, unscrew the faucet handles from the valve body and remove the spout.

You may need a screwdriver or hex wrench if you find a hex nut under the spout.

2. Remove the screws holding the overflow plate in position and remove the plate.

You may have to pull the drain linkage mechanism out of the overflow along with the cover.

3. To loosen the tub drain, push the handles of a pair of slip-joint pliers into the tub drain, called the spud.

4. Put a large screwdriver between the handles of the pliers and turn the pliers counterclockwise to unscrew the drain from the pipe under the tub, called the shoe.

Taking out the tub

Now’s the time to bring in friends and neighbors with bulging biceps. Don’t attempt to do this job alone. Get two strong helpers to assist with the pulling, lifting, and carrying.

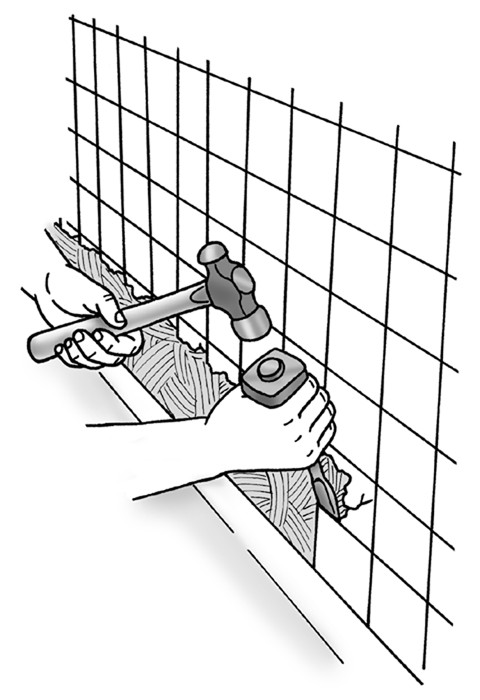

If the tub surround has tiles, use a cold chisel to chip away the lowest course of tile around the tub’s perimeter (see Figure 6-1). Remember to wear safety glasses. If the tub has a fiberglass enclosure, cut the enclosure 6 inches above the tub.

|

Figure 6-1: When removing a tub, carefully chip out the first row of tile with a cold chisel. |

|

To remove a built-in tub, follow these steps:

1. Use a screwdriver or pry bar to remove the screws or nails that attach the tub flange to the wall studs.

2. When the tub is free from the walls, use a pry bar to loosen the front of the tub from the floor.

Place the end of the bar between the floor and the tub and pry up to raise the tub off the floor. If your floors are tile, you may need to break out a course or two of floor tiles as you did for the walls tiles.

3. Insert several scraps of plywood or cardboard skid under the front edge of the tub.

The wood protects the floor and makes it easier to pull the tub out of its enclosure.

4. Slide the tub onto the plywood and pull the tub away from the wall (see Figure 6-2).

|

Figure 6-2: Use a wood or cardboard skid when removing a tub. |

|

The challenge is to lift and move the tub safely down a steep staircase. Be careful — making turns can get dicey.

If the tub won’t budge, you may have to cut it in pieces. A reciprocating saw with a metal cutting blade cuts through a steel or fiberglass tub. Use a sledgehammer to break up a cast-iron tub, but cover it with an old dropcloth first. To protect yourself, wear long sleeves, long pants, and heavy leather workgloves. And don’t forget safety glasses to protect your eyes.

Putting In a New Tub

Installing a tub isn’t an easy do-it-yourself project because it involves working with a large, heavy object in a small space. If you have any misgivings about doing it, hire a plumber who has the experience to install it and the license to hook up the fixtures.

If you want to do it yourself, inspect the new tub before you start the installation. Measure its dimensions and check them against the size of the opening. Make sure that the drain outlet is at the correct end of the tub. Look for signs of damage and then protect the tub surface with a dropcloth.

Before you get started on the installation, inspect the floor joists and look for joists that have been weakened by rot or were cut to remove pipes. Remove a rotten joist and replace it. Reinforce a bad joist by fastening a new joist to the existing one with machine bolts. Then install a new subfloor over the joists if necessary.

Gather the following tools and materials to install an acrylic or platform tub.

1-inch galvanized roofing nails

1-inch galvanized roofing nails

2 x 4s

2 x 4s

Carpenter’s level

Carpenter’s level

Construction adhesive

Construction adhesive

Electric drill and bits

Electric drill and bits

Measuring tape

Measuring tape

Mortar mix

Mortar mix

Pipe wrench

Pipe wrench

Plumber’s putty

Plumber’s putty

Screwdriver

Screwdriver

Silicone caulk

Silicone caulk

Trowel

Trowel

Wood shims

Wood shims

Woodworking tools

Woodworking tools

Installing an acrylic tub

An acrylic tub is set in a bed of cement — check the manufacturer’s recommendations. The sides are screwed or nailed through flanges into wall studs. The tub is supported on a 1-x-4-inch ledger nailed to the wall studs. In models with integral supports under the tub, you can shim under the supports to compensate for a slightly out-of-level floor. Then you connect the overflow assembly to the tub drain and main drain line, connect faucets to the water supply lines, and hook up plumbing pipes and drain lines.

Installing a ledger board

The first step in installing a tub is to set in place a ledger board that supports the edges of the tub that contact the walls of the tub enclosure. Follow these steps:

1. Push the tub into the enclosure to mark the top of the flange on the wall studs with a pencil.

2. Measure and mark the location for the top of the ledger, usually about 1 inch below the first mark.

Use the manufacturer’s specifications or measure the distance from the top of the flange to the underside of the tub; it’s usually 1 inch.

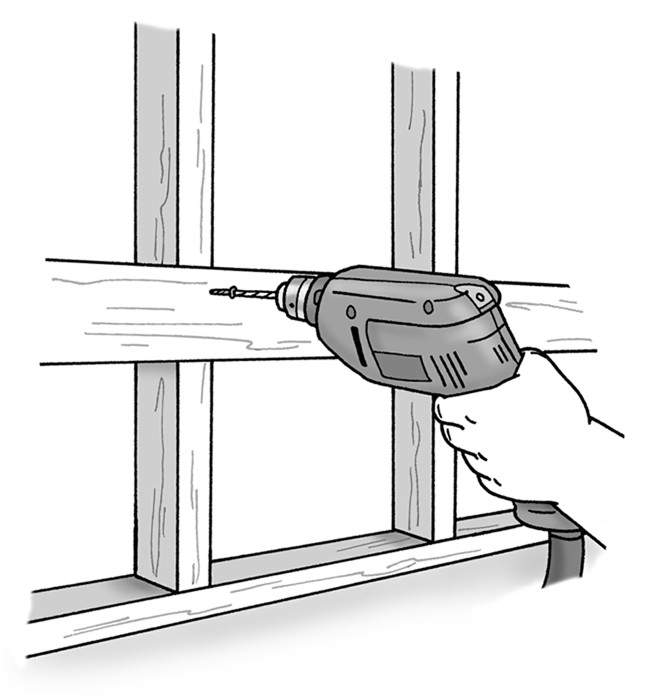

3. Use coarse drywall screws to fasten the ledger board horizontally and level across the back wall of the alcove (see Figure 6-3).

|

Figure 6-3: Installing a ledger around the perimeter of the tub enclosure. |

|

4. Fasten shorter ledger boards to the ends of the enclosure, level with the board you install on the back wall.

Doing so creates a continuous ledge on the tub enclosure wall for the tub to rest on.

Hooking up the plumbing

It’s easier to install the drain and overflow pipes on the tub before it’s permanently installed in the enclosure. Turn the tub over or rest it on its side and then follow these steps:

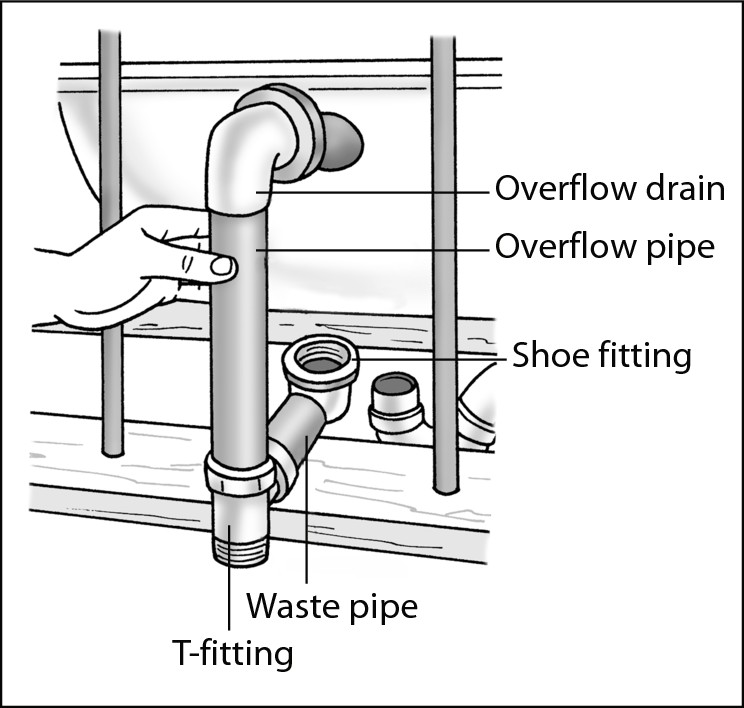

1. Follow the manufacturer’s directions and assemble the shoe fitting, which is placed under the tub and the waste pipe.

2. Assemble the overflow fitting with the overflow pipe.

Insert the ends of the overflow pipe and waste pipe in the T-fitting (see Figure 6-4).

|

Figure 6-4: Installing an overflow drain. |

|

3. Put this assembly in place to check that shoe and overflow align with the openings in the tub.

4. Place a bead of plumber’s putty around the drain flange and wrap Teflon pipe tape around the threads on its body.

5. Place a rubber washer on the shoe and position the shoe under the tub in alignment with the drain flange.

6. Screw the drain flange into the shoe.

7. Tighten the drain flange.

Place the handles of a pair of pliers in the drain flange. Insert the blade of a large screwdriver between the handles of the pliers and use it as a lever to tighten the drain flange.

8. Place a rubber washer on the overflow drain and install the overflow cover with the screws provided.

You may want to leave the drain linkage and pop-up assembly out of the tub until you set it in place.

Securing the tub

Follow these steps to apply mortar to the subfloor of the tub:

1. Mix a batch of mortar according to the package directions.

2. With a notched trowel, spread a 2-inch layer of mortar on the subfloor where the tub will sit.

3. Lift the tub in place and position it so that it’s tight against the walls.

Hold a carpenter’s level on the tub and check that it’s level. If not, adjust it by placing wood shims under the tub.

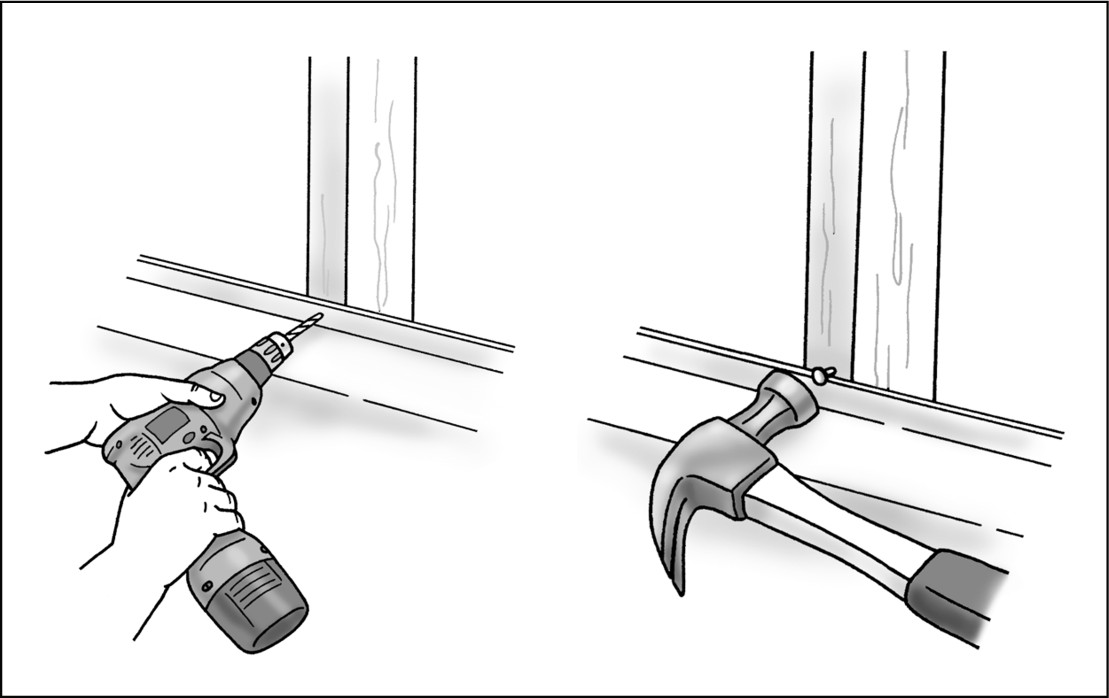

Finishing up

After the tub is level, you secure it to the enclosure to keep it that way. Secure the flange to the studs by driving 1-inch galvanized roofing nails through the holes in the flange (see Figure 6-5). If the tub is fiberglass, drill holes at each stud. If it’s a steel or cast-iron tub and it has no holes, or they don’t align with the studs, drive the nails above the top of the flange so that the head of each nail engages the flange. Hammer carefully so as not to damage the tub.

|

Figure 6-5: Securing the tub flange to the wall studs with roofing nails. |

|

Installing a platform tub

When a tub becomes the centerpiece of a bathroom, it’s often enclosed in a framed platform that’s given a surface of tile, wood, or other finishing material. The project may require reinforcing existing floor framing in addition to the construction skills and tools to build the platform and plumbing know-how and tools to install the unit, its water and drain lines and faucets. If you are so gifted, follow the tub manufacturer’s directions for the wiring and plumbing requirements and use these guidelines for building a platform. If you prefer to sit this one out, hire a contractor for all or part of the task. In either case, the following sections tell you what’s involved.

Doing the prep work

Follow the tub manufacturer’s suggestions and design a platform that’s at least a foot wider and longer than the tub and high enough to support it above the existing floor. Build the framework for the platform from 2 x 4s and 3/4-inch exterior grade plywood, using nails and deck screws to fasten them together. Keep in mind that the height of the platform should allow for the plywood decking plus the thickness of backerboard, thinset mortar, and tile and allow a 1/4-inch expansion gap between the tub and the finish material. If you’re installing a whirlpool tub, make an opening in the framework for an access panel for the pump and drain.

Constructing the platform for a tub isn’t difficult, but it requires accurate measuring and cutting. This project is very straightforward for a carpenter, so you may be well served to hire out this phase.

1. Check the height of the platform that your tub requires and calculate the height of the platform wall studs.

For example, if the tub requires a 36-inch-high platform, the studs should be cut to 31 3/4 inches. This length allows for the thickness of the top and bottom 2-x-4 plate, the 3/4-inch plywood, backerboard, mortar, and tile.

2. Nail the studs to the top and bottom plates to form the walls for the platform.

3. Secure the wall framework to the floor with nails, and use deck screws to cover the framework with plywood to make the deck.

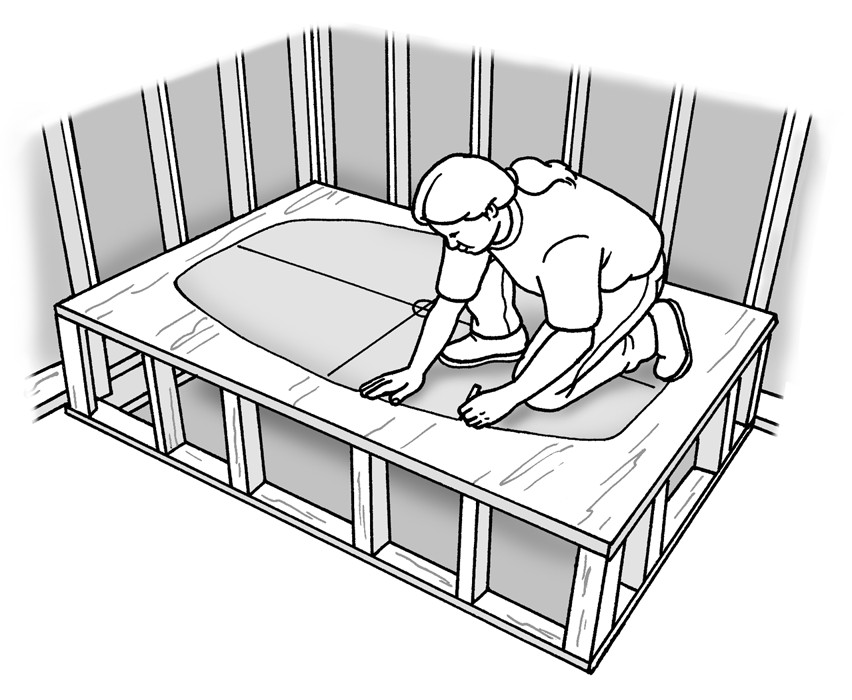

4. Use a jigsaw to cut an opening in the deck for the tub, either by using the template provided by the manufacturer or after carefully marking the dimensions for the rough opening (see Figure 6-6).

5. Follow the faucet manufacturer’s instructions for measuring and marking the rough-in locations for supply pipes.

6. Drill the holes in the deck and then rough in the water supply and drainpipes.

|

Figure 6-6: Laying out the outline of the tub so that it’s centered on the deck. |

|

Dropping in the tub

After the platform is built and the plumbing is roughed in, you place the tub in the platform. It’s easier to install a whirlpool tub after you’ve installed the tile on the top surface of the platform, but you may not have enough room to move the large tub around the bathroom as you build the partitions. If that’s the case, install the tub before the tile. Both options are discussed here.

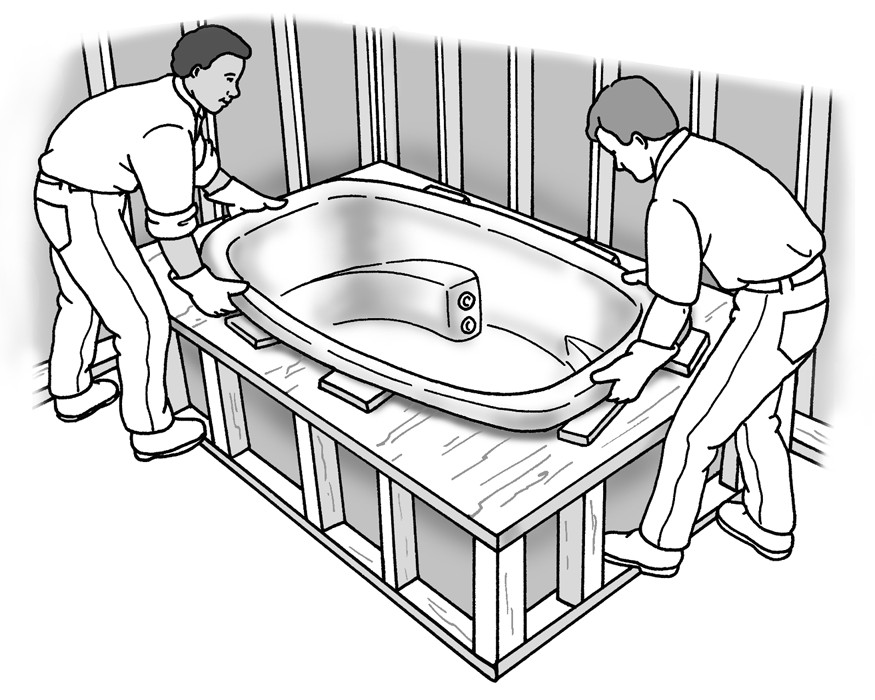

Follow these steps to secure the tub in the platform:

1. If the tub must be installed before the tile, place wood blocks on the platform along the perimeter of the cutout to support the tub at the correct height above the plywood deck.

The wood blocks should be the thickness of the thinset mortar, backer board, thinset mortar, and tile and be positioned as shown in Figure 6-7.

If the tub can be installed after the tile is installed on the plywood deck, the blocks are not needed. The tub will rest directly on the tile.

2. Apply a layer of mortar to the floor below the tub for additional support (following the manufacturer’s directions).

3. Carefully lift the tub by its rim and set it in the cutout hole, with the help of at least one other person (see Figure 6-7).

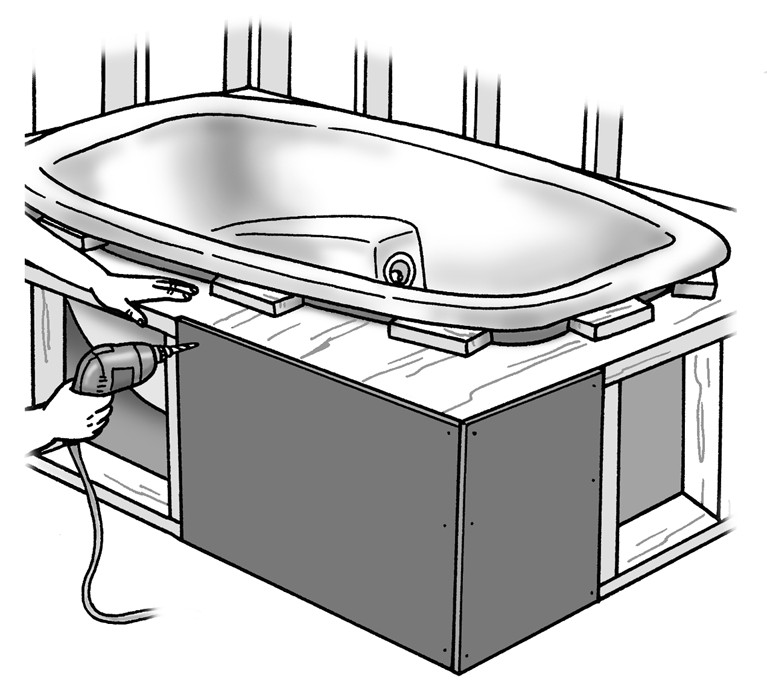

4. After the mortar has set, install the drain assembly and connect the wiring to the motor and controls.

5. Complete the installation by finishing the surface of the deck and platform.

Install backerboard to the sides and top of the platform with backerboard screws (see Figure 6-8). Apply thinset mortar and install the tile or other surface material.

|

Figure 6-7: Lifting the tub very carefully into position in the opening. |

|

|

Figure 6-8: Finishing the platform. |

|

6. Install the faucet on the deck of the platform. Run the riser tubes from the faucet to the rough-in water supply pipes.

7. After the tiling work is completed apply caulk to fill the joints between the tub and the tile and between the tiled base of the platform and the finished floor.

When Removing a Bathtub Is Mission Impossible

If you can’t remove an unattractive tub, you have two options: refinishing the surface or having a liner made to go over it. These aren’t do-it-yourself options. A new tub liner, which costs about $1,000, lasts longer than having a tub refinished, which costs anywhere from $200 to $500. To complete your tub’s transformation, replace the old fixtures with new ones.

Reglazing

If the overall tub surface is worn or damaged, one option is having it refinished through a process called reglazing. First, the technician thoroughly scrapes the surface of the bathtub and then applies an etching solution to dull the old finish. Then the technician sands it thoroughly, finishing up the project by spraying the surface with a new polyurethane finish and polishing it. Because of the heavy-duty sanding, this can be a messy job that sends sanding dust throughout your house unless proper precautions are taken, such as using a window exhaust fan and closing of adjacent rooms.

Adding a tub liner

The second choice in covering up an old tub’s surface is having a tub liner custom-made to fit over the surface of the old tub. An installer measures the old tub. Then a matching acrylic model is made, using the tub manufacturer’s specifications for the contours and the exact location of plumbing cutouts. The liner is trimmed to fit, slipped over the old tub, and fastened with adhesive. You can also have matching wall panels made and installed at the same time.