Chapter 3

Drilling, Driving, and Fastening

In This Chapter

Holding your work together before you commit to it

Holding your work together before you commit to it

Finding the best drill to buy . . . and some to rent

Finding the best drill to buy . . . and some to rent

Figuring out which hammer is right for the job

Figuring out which hammer is right for the job

Exploring basic wrenches, pliers, and other gripping tools

Exploring basic wrenches, pliers, and other gripping tools

Creating a tight hold with clamps and glue

Creating a tight hold with clamps and glue

Looking down the barrels of stapling and caulking guns

Looking down the barrels of stapling and caulking guns

C arpentry and related work, such as hardware installation, invariably involves assembly and, one way or another, attaching things together. In this chapter, you find out about the tools and techniques involved in this work — and how to use them safely without gluing your fingers together or nailing your shoes to the floor.

Trial Assembly Pays Off

You may have heard the old tip “Measure twice and cut once.” The extra moment it takes to double-check your measurements often prevents disasters, or at least saves the time required to correct problems that arise from an error in measuring. The same principle applies to the assembly stage. Double-check your cut, positioning, or fit before final assembly. Make a habit of doing a trial assembly or dry fit before you nail, glue, or screw parts together.

If you’re nailing, a dry fit can be as simple as holding the work, such as a piece of trim or length of siding, in place to make sure that it fits well before driving any nails. In other situations, you may need to tack the piece in place, which is what carpenters call it when they secure a workpiece with a minimum number of nails, driven just deep enough to hold the work in place but shallow enough that they can be removed easily if the piece must be repositioned or recut.

Trial fitting is especially important when glue and adhesive are involved. After you apply glue or adhesive, you’re, well, stuck if the work doesn’t fit. At best, you’d have glue all over a piece you need to recut. At worst, you’d be dripping glue all over the place and then tracking it through the house. Always trial fit before assembling with contact cement (which sets instantly) and other fast-drying glues. Disassembly without damaging the work is difficult or impossible.

Don’t think you’re home free just because you’re using screws. Sure, you can easily remove them, but you’ve still got the holes you made in the process. Even if you can recut a too-long board or use a too-short board, the holes may not be where they need to be. Similarly, if the piece needs to be moved slightly, the holes in the base material may need to be plugged and redrilled. So hold, tack, brace, or clamp the work before you drill pilot holes or drive screws.

Drilling and Power Driving

Today’s 3/8-inch variable-speed reversible drill/driver, available in plug-in and cordless models, uses steel screw-driving tips to drive in or remove screws and various bits and accessories to drill holes, sand wood, mix piña coladas, and other important carpentry tasks.

For decades, the electric drill has been the top-selling power tool and the first power tool that most people buy. A while after the drill’s emergence, the makers added variable-speed triggers and reversing motors. This new tool, called a drill/driver, is more versatile. One tool performs both high-speed and low-speed drilling operations and, most significantly, drives and removes screws easily.

More recent improvements have put the drill/driver at the top of everyone’s power tool wish list. Batteries replace cumbersome and inconvenient electrical cords, adjustable clutches let you control the torque (driving force), and with a keyless chuck, you can change bits or accessories in a flash. Simply grasp the keyless chuck with one hand and activate the tool with the other, in forward or reverse, depending on whether you’re installing or removing a bit.

Having made driving screws almost as easy as pounding nails, the drill/driver brought on a parallel change in screw design and a dramatic reduction in swollen thumbs. Tapered, slotted-head wood screws have been widely replaced by straight-shank, Phillips-head screws. The changes also have spawned a line of screw-driving accessories, the most significant of which is the magnetic bit holder.

You may want or need to purchase or rent other drills for a particular task. A hammer drill, for example, adds a high-speed pounding force to the rotary action for drilling concrete, tile, your mother-in-law’s meat loaf, and other hard materials. A right-angle drill fits in tight places that a standard drill won’t because the shaft (and therefore the bit) is perpendicular to the body.

Accessorizing your drill/driver

Accessories turn this hole-drilling tool into a grinder, a sander, a carving tool, and even a fluids pump. Explore the possibilities, but start with these essentials:

An index of high-speed steel twist bits: Buy a large index (a metal box with labeled slots for various size bits). Then, depending on your budget and the amount of use you anticipate, either buy a small set of bits and add to them as needed or bite the bullet and go for a full 64-bit set. If you own a 3/8-inch drill (the size we recommend) and buy twist bits that are over 3/8-inch diameter, make sure that the chucked portion of the shaft is 3/8 inch in diameter or smaller.

An index of high-speed steel twist bits: Buy a large index (a metal box with labeled slots for various size bits). Then, depending on your budget and the amount of use you anticipate, either buy a small set of bits and add to them as needed or bite the bullet and go for a full 64-bit set. If you own a 3/8-inch drill (the size we recommend) and buy twist bits that are over 3/8-inch diameter, make sure that the chucked portion of the shaft is 3/8 inch in diameter or smaller.

A set of spade bits: These flat, wood-boring bits are required for deeper holes and holes with diameters larger than 1/2 inch. They work better at high speeds.

A set of spade bits: These flat, wood-boring bits are required for deeper holes and holes with diameters larger than 1/2 inch. They work better at high speeds.

A set of multibore or screw pilot bits: Although many situations allow you to drive screws without the necessity of drilling pilot holes, most often you try to avoid those loveliest of sounds — wood splitting and screw heads snapping off. These multi-duty combination drill bits eliminate the need to change bits because one bit bores the clearance (or shank) hole and the pilot (or lead) hole, and when called for, the countersink and counterbore, all in one easy step.

A set of multibore or screw pilot bits: Although many situations allow you to drive screws without the necessity of drilling pilot holes, most often you try to avoid those loveliest of sounds — wood splitting and screw heads snapping off. These multi-duty combination drill bits eliminate the need to change bits because one bit bores the clearance (or shank) hole and the pilot (or lead) hole, and when called for, the countersink and counterbore, all in one easy step.

An assortment of Phillips and standard bits and a magnetic bit holder: Start with the following five bits: Phillips (#1 and #2) and slotted (1/4, 3/16, and 7/32). Buy bits for more exotic screws, such as the Pozidrive, square-drive, and Torx, as needed. The purpose of the magnet is to hold the screw and free up your other hand for more important things, such as holding the work, digging for the next screw, or scratching your nose.

An assortment of Phillips and standard bits and a magnetic bit holder: Start with the following five bits: Phillips (#1 and #2) and slotted (1/4, 3/16, and 7/32). Buy bits for more exotic screws, such as the Pozidrive, square-drive, and Torx, as needed. The purpose of the magnet is to hold the screw and free up your other hand for more important things, such as holding the work, digging for the next screw, or scratching your nose.

A set of carbide-tipped masonry bits: Buy bits ranging from 1/8 inch to at least 3/8 inch. These bits usually come in a handy plastic storage box. Use masonry bits for concrete, brick, other masonry products, plaster, and tile. (Never use steel twist bits, which quickly become dull and produce more smoke than a cheap cigar.)

A set of carbide-tipped masonry bits: Buy bits ranging from 1/8 inch to at least 3/8 inch. These bits usually come in a handy plastic storage box. Use masonry bits for concrete, brick, other masonry products, plaster, and tile. (Never use steel twist bits, which quickly become dull and produce more smoke than a cheap cigar.)

The following are accessories that you may well need someday, but we suggest that you purchase them as the need arises:

Holesaw: A holesaw is primarily for cutting large holes in metal or wood. (If you thought that a holesaw is twice as big as a “half saw,” please put down this book before you hurt yourself.) One type has a cup-shaped cutter with teeth along the rim. Another has band-type blades. Each type of cutter fits on a spindle, called a mandrel, which also holds a pilot bit that enters the work and holds the holesaw in position as the large cutter enters the work. Holesaws come in several sizes, up to 5 inches or more, but the only application you’re likely to need one for is to bore a 2 1/8-inch-diameter hole in a door for a lockset. It’s the only practical, affordable tool to make that size hole.

Holesaw: A holesaw is primarily for cutting large holes in metal or wood. (If you thought that a holesaw is twice as big as a “half saw,” please put down this book before you hurt yourself.) One type has a cup-shaped cutter with teeth along the rim. Another has band-type blades. Each type of cutter fits on a spindle, called a mandrel, which also holds a pilot bit that enters the work and holds the holesaw in position as the large cutter enters the work. Holesaws come in several sizes, up to 5 inches or more, but the only application you’re likely to need one for is to bore a 2 1/8-inch-diameter hole in a door for a lockset. It’s the only practical, affordable tool to make that size hole.

Doweling jig: In many woodworking projects, wooden dowels reinforce joints. You drill holes in the mating pieces and insert a dowel. The doweling jig precisely locates the holes and sets the depth, so that when you join the pieces, they align perfectly. Today, professionals favor the biscuit jointer. It’s worth the investment if you do a lot of woodworking, but doweling is fine for the occasional woodworker.

Doweling jig: In many woodworking projects, wooden dowels reinforce joints. You drill holes in the mating pieces and insert a dowel. The doweling jig precisely locates the holes and sets the depth, so that when you join the pieces, they align perfectly. Today, professionals favor the biscuit jointer. It’s worth the investment if you do a lot of woodworking, but doweling is fine for the occasional woodworker.

Sanding, grinding, and other abrading tools: Take advantage of the drill’s versatility with these accessories that enable you to shape and smooth wood, clean and debur metal, remove paint, and perform a host of other tasks.

Sanding, grinding, and other abrading tools: Take advantage of the drill’s versatility with these accessories that enable you to shape and smooth wood, clean and debur metal, remove paint, and perform a host of other tasks.

Portable drill stand: Precision or repetitive drilling is ideally done on a drill press, a heavy piece of stationary equipment that few remodeling professionals even own. If you don’t have a drill press, lock your drill into one of these handy, portable stands for easier and more accurate drilling.

Portable drill stand: Precision or repetitive drilling is ideally done on a drill press, a heavy piece of stationary equipment that few remodeling professionals even own. If you don’t have a drill press, lock your drill into one of these handy, portable stands for easier and more accurate drilling.

Bit-extension tool: Lock a twist drill or spade bit into the end of an extension shaft to extend the reach or to drill very deep holes. This tool gets a lot of work when you rewire an old house. To fish wires from one place to another, you often need to drill holes at an angle through a wall, into a stud cavity, and through a floor or ceiling joist bay to the floor below or above — a distance of 12 inches or more.

Bit-extension tool: Lock a twist drill or spade bit into the end of an extension shaft to extend the reach or to drill very deep holes. This tool gets a lot of work when you rewire an old house. To fish wires from one place to another, you often need to drill holes at an angle through a wall, into a stud cavity, and through a floor or ceiling joist bay to the floor below or above — a distance of 12 inches or more.

Flexible shaft: You can literally drill around corners by securing your drill bit in the end of a flexible shaft. It’s not something you use every day, but it’s still great to own.

Flexible shaft: You can literally drill around corners by securing your drill bit in the end of a flexible shaft. It’s not something you use every day, but it’s still great to own.

Watch your speed!

After you determine the proper bit to use, it’s time to put on safety goggles and, if required, a dust mask. Then figure out the speed that you want that bit to turn and the amount of pressure to exert (called feed pressure ). We suppose you can memorize a chart full of specs on the optimal speed for drilling holes in dozens of common materials, but all you really need is one general rule, a little common sense, and some trial-and-error. In general, the larger the hole and the harder the material, the slower the speed you want to use; and if your drill doesn’t spin as fast as it should, ease up on the feed pressure and take a little more time.

In some cases, you may find it easier to start slow and pick up speed after you establish the location. Similarly, stepping up from smaller-diameter bits until you reach the desired hole diameter is a useful trick when drilling in concrete, masonry, metal, and other hard materials. Lubrication — oil for metal drilling and water for concrete or masonry drilling — cools the bits and improves the efficiency of the cutter.

Assuming that you’re using the proper bit/cutter and that it’s sharp and properly secured in the tool, adjust your drilling speed and feed pressure if any of the following warning signs pop up:

The bit or other cutter fails to do its job.

The bit or other cutter fails to do its job.

The bit or cutter jams or turns too slowly.

The bit or cutter jams or turns too slowly.

The bit or cutter overheats, as evidenced by smoke or blackening of the workpiece or bit.

The bit or cutter overheats, as evidenced by smoke or blackening of the workpiece or bit.

The drill motor strains or overheats.

The drill motor strains or overheats.

As long as you can maintain control, you can often drive screws at a drill/ driver’s maximum speed. A screw gun, a single-purpose professional tool designed exclusively for driving screws, operates at speeds two or three times faster than the fastest drill/driver. However, if a screw is going in at a bazillion miles a second, you can’t rely on the reaction of your trigger finger to stop the bit at just the right point. You’ll likely drive the screw too deep, strip the screw head, snap the screw in half, or damage your workpiece — or all the above. Better drill/drivers have an adjustable clutch, which limits the torque. Basically, when the screw is seated, the bit stops turning.

Drilling techniques

To accurately locate a hole, called spotting, it’s often helpful to create a small indentation to guide the bit’s initial cut and prevent it from spinning out of control like a drunken figure skater. The harder the surface and the greater the accuracy required, the more advisable it is to spot a hole before drilling. In soft wood, this step is as simple as pressing the bit or a sharp pencil point into the wood. In hard wood, you may want to use an awl. In metal, it’s virtually required that you use a hammer and center punch. To further prevent the bit from wandering off course, hold the tool perpendicular to the surface. If you need to drill at an angle, tilt the drill after the bit has started to penetrate, or clamp an angle-guide block onto your work.

Grip the drill firmly, with two hands if possible, for better control. Heavy drills have higher torque and may even include a side handle so that you can control the tool if the bit jams in the work and the drill keeps turning. Whenever possible, clamp workpieces that may not be heavy enough to stay put under a drilling load.

Driving Screws

Despite the overwhelming popularity of the drill/driver, screwdrivers are still an essential item for every homeowner. You’ve probably heard the saying “Use a tool only for its intended purpose.” Very often, you can injure yourself, ruin a tool, or damage your work if you fail to heed that advice. However, if using a screwdriver for a task other than driving screws were a crime and the punishment were banishment from hardware stores, the aisles would be empty.

The first rule for driving screws is to use a driver that matches the type and size screw you’re driving. The majority of screws are either Phillips screws, which have a cross-shaped recess in the head and require a Phillips screwdriver, or slotted screws, which have a single slot cut across the diameter of the screw head and require a standard driver.

You get the best deal and are prepared for most screwdriving situations if you buy an assortment of screwdrivers. At a minimum, you need two standard drivers, a 3/16-inch cabinet and a 1/4-inch mechanics, and two Phillips drivers, a 4-inch #2 and a 3-inch #1.

Alternately, you can buy a 4-in-1 or 6-in-1 driver. The 4-in-1 has a double-ended shaft, two 3/16-inch and 9/32-inch standard, and #1 and #2 Phillips interchangeable bits (tips). In the 6-in-1 model, the two ends of the shaft serve as a 1/4-inch and 5/16-inch nutdriver. Buy other size screwdrivers as needed. One advantage of these multidrivers is that they accommodate different bits; when you run across screws with square holes, star-shaped holes, or other tip configurations, you need to buy only the appropriate tip, not a whole other tool.

The way to use a screwdriver is essentially obvious, but we have a few points worth mentioning. First, don’t hold the tool between your knees or teeth — you’ll get lousy torque pressure. Always match the driver to the fastener. Failure to do so inevitably deforms the screwhead, sometimes to the point where you can no longer twist it out or in. This is particularly true with brass screws (which are easily damaged because brass is relatively soft) and when the screw is unusually tight or even stuck.

If you’re trying to draw and fasten two things together with a flathead screw, for example two pieces of wood, join the two pieces together and use one of the following approaches:

Clamp the two pieces together and, using a bit that’s a little smaller than the diameter of the screw, drill a pilot hole as deep as the screw is long. Finish by using a countersink bit to bore a conical hole that suits the screwhead. Clamping is necessary because the screw tends to force the two pieces apart as it enters the second piece.

Clamp the two pieces together and, using a bit that’s a little smaller than the diameter of the screw, drill a pilot hole as deep as the screw is long. Finish by using a countersink bit to bore a conical hole that suits the screwhead. Clamping is necessary because the screw tends to force the two pieces apart as it enters the second piece.

Alternately, bore the appropriate pilot, clearance, and countersink holes before driving the screw. Using a bit that’s a little smaller than the screw’s diameter, bore a pilot hole that’s equal to the screw’s length through both pieces. Then, using a bit that equals the diameter of the screw, bore a clearance hole through the top piece only. A screw pilot or multibore accessory bit bores all three holes at once and is available in sets to suit various screw sizes.

Alternately, bore the appropriate pilot, clearance, and countersink holes before driving the screw. Using a bit that’s a little smaller than the screw’s diameter, bore a pilot hole that’s equal to the screw’s length through both pieces. Then, using a bit that equals the diameter of the screw, bore a clearance hole through the top piece only. A screw pilot or multibore accessory bit bores all three holes at once and is available in sets to suit various screw sizes.

Predrilling for screws is always best and makes driving screws by hand much easier. Predrilling is essential for most finish work (where neatness is important) and to prevent splitting when screwing into hardwoods, plywood, end grain, or near the ends of a board. On many occasions, however, you may not need to drill pilot holes or countersinks, especially if you use a drill/driver. The best screws to use in wood without pilot holes have bugle heads (similar to flathead screws), straight shafts, and coarse threads.

Although you can buy a depth gauge for drill bits, a piece of tape (masking, electrical, duct, or whatever) wrapped around the shaft of a bit tells you when to stop drilling.

Sometimes, it’s hard for beginners to drill holes at the desired angle — usually perpendicular to the surface. If accuracy is critical, hold a combination square (or a block of wood that you know is cut square) on the surface and against the top of the drill. As long as you keep the drill centered on your guide and in contact with it, the hole will be accurate.

Whenever you need to bore many holes in identical locations in more than one piece of wood, use a template. Take, for example, drilling screw holes to locate knobs on a number of cabinet doors, or drilling a series of holes in the side of a bookcase for plug-in shelf supports. For knobs, the template may be a board with a hole drilled in it that fits over the corner of a cabinet door so that the hole lies in precisely the same spot on each door it’s placed on. For shelf supports, the template may be a 2-foot-long strip of 1/4-inch hardboard with a series of holes so that you only need to align the template with the front or back edge of the bookcase side to drill holes in the exact same spots every time.

You must locate hinges accurately if one half is to mate well with the other, and to ensure that the door is located precisely in its opening. Pilot holes for hinge screws must be exactly centered, or they tend to push the hinge off mark or the screwhead won’t sit flush with the hinge. Any irregularity in the wood grain can push an unguided drill or punch off the mark. A self-centering pilot drill or self-centering punch has tapered ends that fit into the countersink of a screw hole in the hinge, automatically centering the drill bit or punch. One size fits all for the punch, but the drill accessory comes in several sizes to suit #6, #8, and #10 screws.

The Nail Hammer: The Quintessential Carpentry Tool

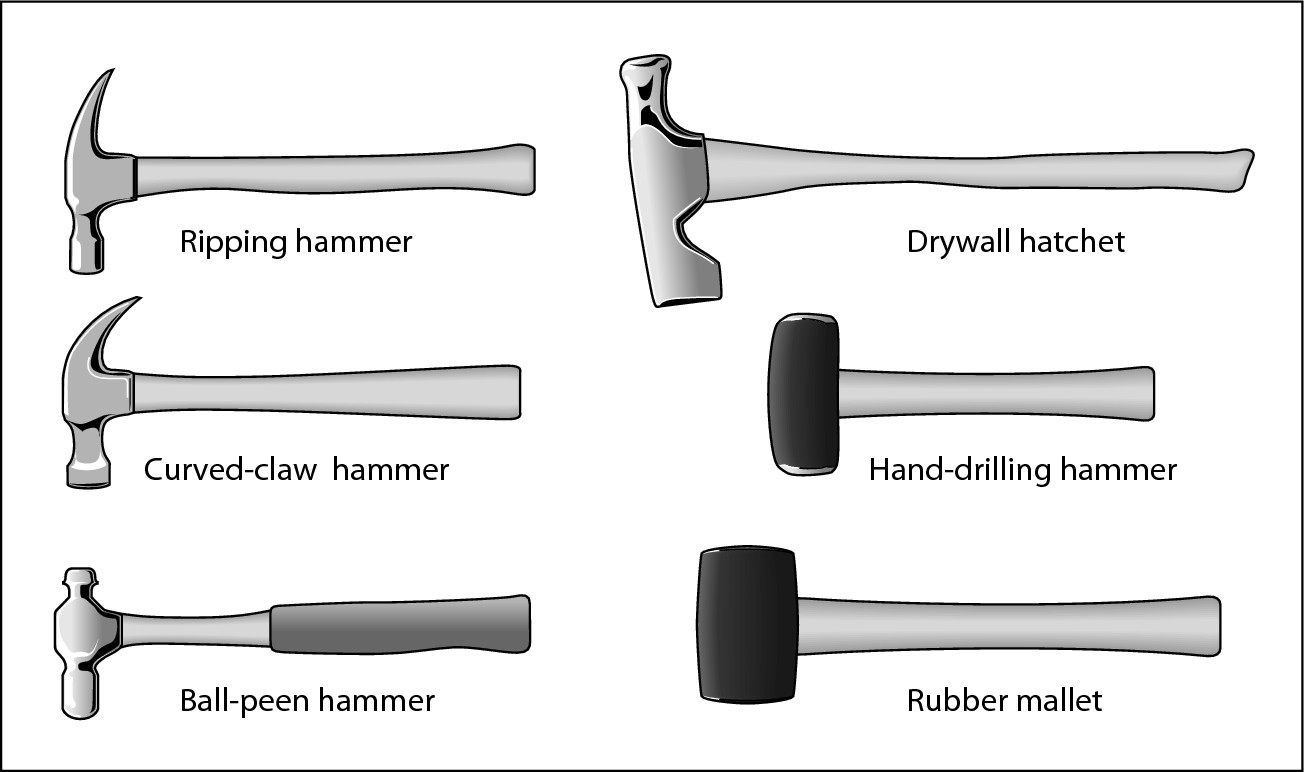

Nail hammers come in two basic types: the one you bought and the one you borrowed from your neighbor three years ago. Just kidding. Actually, the types include the curved-claw hammer, which has a curved nail-pulling claw, and the ripping-claw hammer, which has a straight claw.

For general use, we recommend a 16-ounce, curved-claw hammer with a fiberglass handle. Like wood, fiberglass cushions the vibrations to your hand and arm but has the added advantage that it won’t break under tough nail-pulling conditions. The curved claw on this hammer gives you good nail-pulling leverage (see the section “Pulling nails,” later in this chapter). It’s also heavy enough for most nailing projects, including framing work, as long as the project is modest in scope — such as studding a basement wall.

For a big framing project, you want a heavier hammer. Although it’s heavier to hold, the added weight (and usually a somewhat longer handle) of a 20-ounce ripping hammer does more of the work for you, whether you’re driving large nails, banging things apart, or fine-tuning a dented fender. When a project involves demolition, you can easily force the claw of a ripping hammer between two materials that are fastened or glued together.

Taking precautions

When you want to bang on something other than a nail, think twice before reaching for your nail hammer. When you need to “persuade” something into position but might damage it by using a metal hammer, reach for a rubber mallet.

.jpg)

For the same reason, don’t use a nail hammer to strike cold chisels, masonry chisels, punches, or other hard metal objects, with the exception of nail sets, which are designed to be struck with a nail hammer. Avoid using a nail hammer on concrete, stone, or masonry, too. As a general rule, don’t strike anything harder than a nail with a nail hammer.

Plus, such abuse ruins the face of a nail hammer. If you look closely at the face of a hammer, you see that it isn’t flat. A quality nail hammer has a shiny, slightly convex face with beveled edges to minimize surface denting. Some ripping or framing hammers have a milled face (checkered or waffled), which makes it less likely that you’ll slip off the head of a nail that you don’t strike squarely.

|

Figure 3-1: Use the right hammer for the job. |

|

Driving nails (into wood, not from the store)

Like all carpenters, we’ve had our share of smashed fingers and bent nails. But you can avoid them most of the time by driving nails the right way. Whether you’re nailing a hook for a picture or nailing a 2-x-4 to a garage wall, follow these basic steps for ouch-free installation:

1. To have proper grip, grasp a claw hammer almost at the end of the handle and with your thumb wrapped around the handle.

Thinking that they’ll gain more control, beginners often make the mistake of lining up their thumb on the handle. Not only does this grip fail to improve accuracy, but it’s also inefficient and may cause injury to your thumb. The one exception to this rule is when you’re nailing sideways across your body in a technique called nailing out.

2. Start the nail by tilting it slightly away from you and giving it one or two light taps. Then, move your fingers out of harm’s way and drive the nail with increasingly forceful blows.

You want the handle to be parallel to the surface at the point that it strikes the nail. For rough work, drive the nail home — that is, until the nail draws the pieces tight and is set slightly below the surface. For finish work, stop when the nail is just above the surface. Finish the task with a nail set so that you don’t risk damaging the wood. (See the section “Putting on the finishing touches,” later in this chapter.)

The rules are a little different for a 20-ounce ripping or framing hammer. Unlike a claw hammer, you grasp the handle a little higher — about a quarter of the way up from the end — and keep a little looser grip. Also, take a bigger backswing and use a more forceful downswing. With the heavier hammer and the added driving force, it becomes imperative to keep your other hand well out of harm’s way, preferably behind your back.

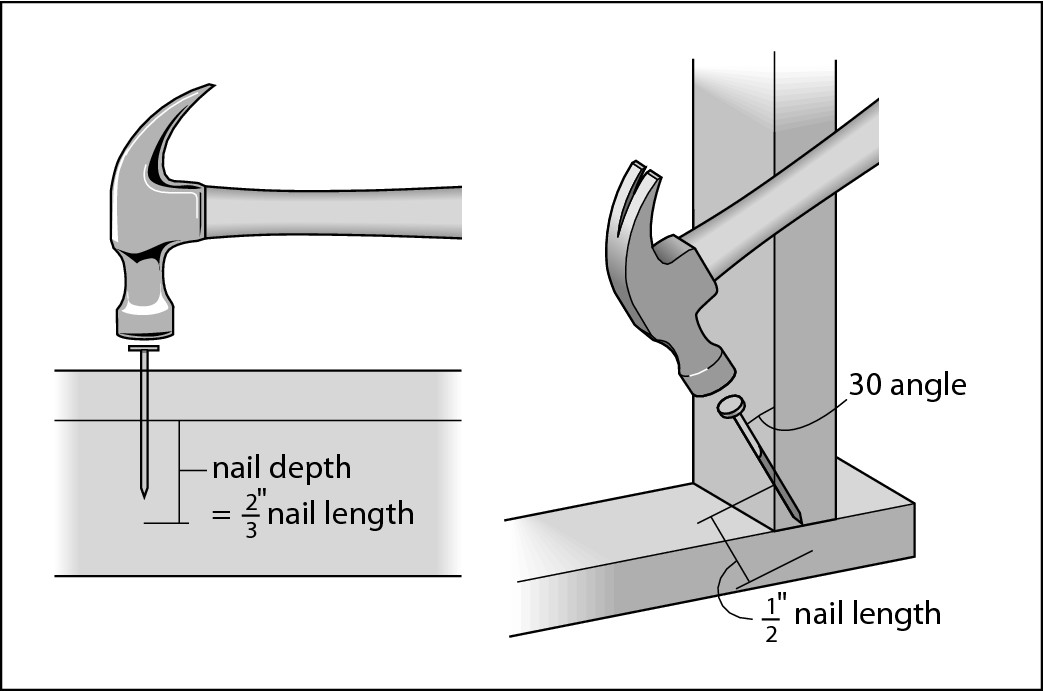

Face-nailing and toenailing

Face-nailing and toenailing (shown in Figure 3-2) aren’t horrible punishments that carpenters inflict on plumbers who cut too-big holes in their floor joists. Rather, they describe the two common ways of nailing objects together.

|

Figure 3-2: Most of the time, you either face-nail (left) or toenail (right). |

|

Most often, you nail through the face of a board and into the backing material. This is called face-nailing. As a general rule, nail through the thinner member into the thicker one whenever possible. The deeper that nail goes into the backing, the more holding power it has.

When you want to secure one piece of lumber to another at a 90-degree angle, such as a wall stud to a sole plate or top plate, you have one or two nailing options, depending on whether you have access to the top of the T. Face- nailing through one board into the end of the mating board is typically the easiest and preferred technique. If you don’t have access, or if the board is so thick that face-nailing through it would be impractical, you must toenail through the end of one board into the face of the other board.

Driving the first nail at such an angle tends to push the board off its mark, so as you drive the nail, you need to back up the board (typically with your foot). It also helps to drive the nail to where it just penetrates one board and then reposition it as necessary before driving one sharp blow. In fact, you may want to assume that driving will tend to push the board past its mark and compensate for that by positioning it a little to the opposite side of the marks.

Blind-nailing

Blind-nailing may sound dangerous, but it’s nothing to worry about. The term describes any nailing technique in which the nail is hidden from sight without the use of putty or wood fillers. In its most common form, the technique is used to secure tongue-and-groove boards, such as solid wood paneling. Nail into the tongued-edge of the board at a 45-degree angle. When you install the next board, its groove conceals the nail, and so on across the wall or floor. The first and last boards typically must be face-nailed as described in the preceding section.

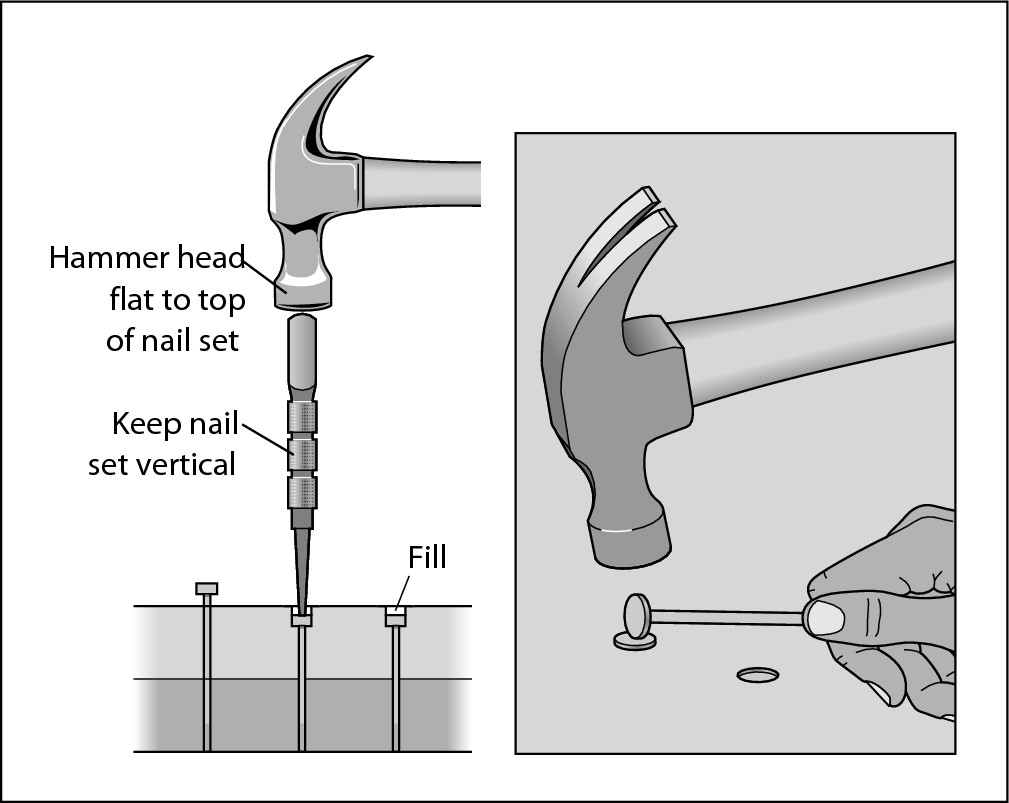

Putting on the finishing touches

In finish work, you generally want to sink the nail head slightly below the surface, as shown in Figure 3-3, and later fill the depression with putty, caulk, or wood filler. For this task, you need a nail set, which comes in sizes ranging from 1/32 to 3/16 inch in 1/32-inch increments to suit various nail head sizes. Buy a set of three and you’re ready for any nail you’re likely to encounter in home carpentry.

|

Figure 3-3: Two nail-setting approaches. |

|

Anytime you need to hold one tool and strike it with another, your fingers are vulnerable. (Theoretically, you can ask for nail-holding volunteers, but you won’t get much interest.) Generally, holding the nail as you hammer isn’t a problem when setting finish nails because you need a relatively minor blow to drive the nail. Such light hammering is easy to control and does less damage if the blow is off the mark.

Pulling nails

When it comes to pulling nails, you have many techniques and tools to choose from. The ones you choose will depend on whether you need to protect the surface, whether the situation allows you to pry the materials apart, whether you can talk someone else into doing this job, and several other factors. To be prepared for most situations, you need a nail hammer, one or two cat’s paw–style nail pullers, and a couple of pry bars.

Try one or more of the following techniques, according to your needs:

Remove the board and then the nails. Most often, the easiest way to take things apart is to either bang or pry them apart or give them to a two-year-old child. Take, for example, trim removal. To do this job while minimizing the damage to either the trim or the surface to which it’s nailed requires a pry bar with a straight, wide blade that’s thin enough to be driven between the materials — a trim bar. (You may want to grind the end of this tool to an even thinner taper to make it easier to insert.) Drive the tapered end of the trim bar behind the trim between two nailing locations. Pull gently toward you and work your way over toward the nailing locations. Then pry it still farther out, using the other end of the trim bar or a larger pry bar, working your way all along the board.

Remove the board and then the nails. Most often, the easiest way to take things apart is to either bang or pry them apart or give them to a two-year-old child. Take, for example, trim removal. To do this job while minimizing the damage to either the trim or the surface to which it’s nailed requires a pry bar with a straight, wide blade that’s thin enough to be driven between the materials — a trim bar. (You may want to grind the end of this tool to an even thinner taper to make it easier to insert.) Drive the tapered end of the trim bar behind the trim between two nailing locations. Pull gently toward you and work your way over toward the nailing locations. Then pry it still farther out, using the other end of the trim bar or a larger pry bar, working your way all along the board.

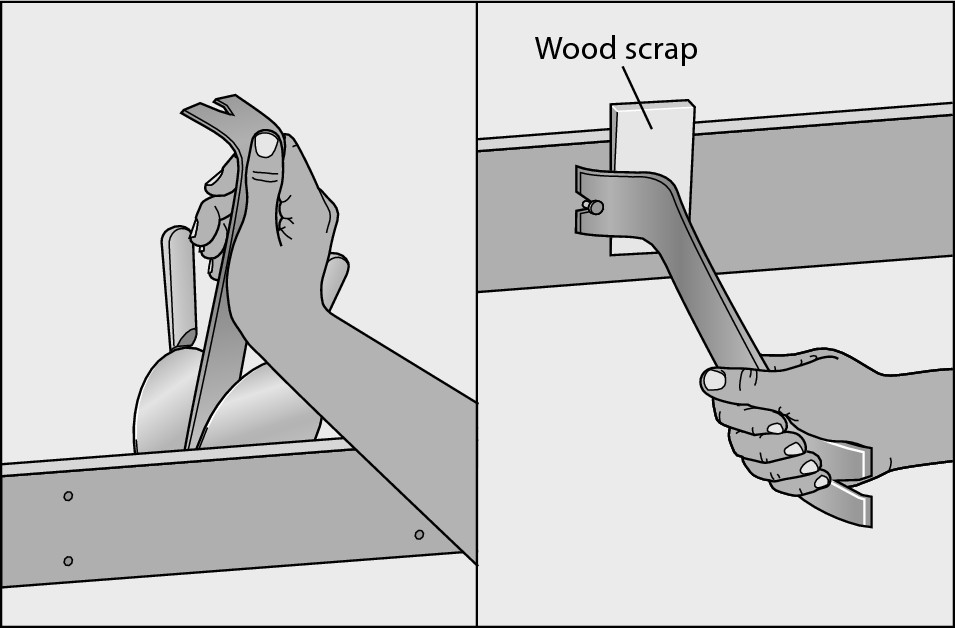

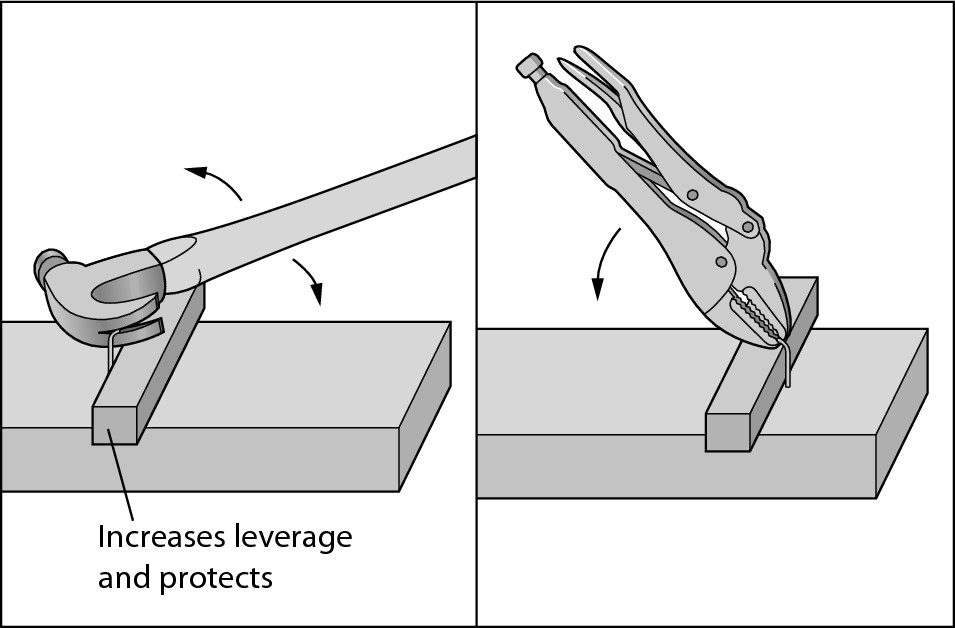

To protect the wall and increase leverage, insert a shim (shingle tip); a thin, stiff material, such as a stiff-blade putty knife; or a wood block between the pry bar and the wall, as shown in Figure 3-4.

Virtually all nailing, demolition, and nail-pulling operations require you to wear proper eye protection.

Pry nails from removed boards. If you’ve pried a board off a surface and nails remain in the board, tap the pointed ends to drive the heads above the opposite surface, at least enough so that you can pull them from the face with a hammer claw or the bent end of a pry bar. If you’re trying to avoid damaging the face of the board (as you might for trim that you’ve removed and plan to reuse), pull the nails through the backside. It’s easy for finishing nails, and with enough force (and soft wood, such as pine), you can pull common nails out backwards, too.

Pry nails from removed boards. If you’ve pried a board off a surface and nails remain in the board, tap the pointed ends to drive the heads above the opposite surface, at least enough so that you can pull them from the face with a hammer claw or the bent end of a pry bar. If you’re trying to avoid damaging the face of the board (as you might for trim that you’ve removed and plan to reuse), pull the nails through the backside. It’s easy for finishing nails, and with enough force (and soft wood, such as pine), you can pull common nails out backwards, too.

To pull the nail, use a hammer as described in the section “Side-to-side technique,” later in this chapter. Alternately, end-cutting pliers (sometimes called nippers) work well, especially with finishing nails. Grasp the nail shaft with the jaws of the pliers as close to the surface as possible. Roll the pliers over to one side, then the other, but don’t grip too hard or you’ll cut the nail.

Pry a little, then pull a little. If you want to protect the surface and can pry a board a little above the surface, do so. Then drive the board back with a sharp hammer blow. The goal is for the board to go back in place and leave the nails standing proud (or humiliated). Protect the surface from the hammer blow with a scrap of wood. Then pull out the nails with a pry bar.

Pry a little, then pull a little. If you want to protect the surface and can pry a board a little above the surface, do so. Then drive the board back with a sharp hammer blow. The goal is for the board to go back in place and leave the nails standing proud (or humiliated). Protect the surface from the hammer blow with a scrap of wood. Then pull out the nails with a pry bar.

Pull nails from the face. If you can’t get behind a board to pry it free, you must attack the nails from the face of the board. For this task, you need a claw-type nail-puller. For rough work, where damage to the surface isn’t a concern, a cat’s paw, which has a relatively wide head, works well. But to minimize damage, you need a puller with a narrower head and sharper jaws that don’t need to be driven so deeply into the wood in order to bite into the nail head. This style also has sharper claws that bite into the shaft of a nail; the wider paw generally needs a head to pull on. You can also find mini versions of these tools for small finish nails.

Pull nails from the face. If you can’t get behind a board to pry it free, you must attack the nails from the face of the board. For this task, you need a claw-type nail-puller. For rough work, where damage to the surface isn’t a concern, a cat’s paw, which has a relatively wide head, works well. But to minimize damage, you need a puller with a narrower head and sharper jaws that don’t need to be driven so deeply into the wood in order to bite into the nail head. This style also has sharper claws that bite into the shaft of a nail; the wider paw generally needs a head to pull on. You can also find mini versions of these tools for small finish nails.

Position the puller with the points of the claw just behind the nail and drive it down into the wood and under the head of the nail. Pull back on the tool with a steady, controlled motion to pull it at least 1/2 inch above the surface. Then use one of the following approaches with a hammer or pry bar.

• Standard approach: After the nail’s head is above the surface, hook onto it with a hammer claw (or with the V-notch on the bent end of a pry bar) and pull the handle of the tool toward you to pry out the nail.

.jpg)

Don’t jerk a hammer in an attempt to free a nail that’s too stubborn to be pulled out with a steady, smooth motion. With the loss of control comes increased risk of injury. The sudden force may break a wooden hammer handle or snap the head off the nail, making it even harder to remove. (Try the next technique if you accidentally snap the head off.) Instead, use a pry bar or nail puller, which gives you the additional leverage required.

• Side-to-side technique: If the nail is long or if you need to protect the surface, slip a scrap of wood under the hammer, as shown in Figure 3-5, to add leverage and enable you to pull out a long nail entirely. To pull large or headless nails, carefully swing the claw into the nail with enough force to make it bite into the shaft as close to the surface as possible. Then push the hammer over sideways, and the nail will come out about 1 inch. Reposition it and push sideways in the opposite direction to pull it another inch. If you have a good-quality hammer with a sharp claw, it won’t slip off the nail’s shaft. After you’ve sufficiently loosened the nail, use the standard pull-toward-you approach to pull it out the rest of the way.

|

Figure 3-4: Minimizing damage to a board being removed. |

|

|

Figure 3-5: A block of wood increases leverage and protects the surface. |

|

Fastening with Staples

A staple gun is handy for many remodeling projects, such as securing insulation, ceiling tile, or plastic sheeting, as well as for such household repairs and projects as recovering a seat cushion or rescreening a porch. The tool is available in manual and electric models. Each has pros and cons, but given the typical limited use, it probably doesn’t matter which you choose.

.jpg)

A dial on the hand-powered model regulates the force of the blow. The harder the material you’re stapling into and the longer the staple, the more force you need. To ensure that all the force that you set is delivered, press the stapler down firmly as you fire the staple. If an occasional staple stands proud, give it a tap with a hammer — not the stapler.

Getting Down to Nuts and Bolts

Product installations often involve nuts and bolts, and many carpentry projects make use of lag bolts and a variety of other metal anchors and fasteners that you can’t grab with a screwdriver or nail hammer. In addition, you’ll often find that you need a firm hold on a variety of nonfastener items such as pipes, product and machinery parts, wiring, hardware, and so on. These tasks all require one of the following gripping tools.

Pliers: Grippy, grabby, and pointy

Slip-joint pliers have toothed jaws that enable you to grip various-sized objects, like a water pipe, the top of a gallon of mineral spirits, or the tape measure you accidentally dropped into the toilet. Because its jaws are adjustable, slip-joint pliers give you leverage to grip the object firmly. This tool is on everyone’s basic list of tools, but to be honest, few people use it very often. Instead, we prefer locking pliers (commonly known by one brand name, Vise-Grip). Locking pliers easily adjust to lock onto pipes, nuts, screws, and nails that have had their heads broken off and practically anything that needs to be held in place, twisted, clamped, or crushed.

For occasional minor electrical work and repairs, every tool kit needs a pair of long-nose pliers (often mistakenly called needle-nose pliers, which have a much longer, pointier nose). Long-nose pliers cut wire and cable, twist a loop on the end of a conductor to fit under a screw fitting, and, turned perpendicular to the wires, do a fair job twisting wires together. If you find yourself doing more than occasional electrical work, pick up a pair of lineman’s pliers, too. This tool does a better job of twisting connections and cutting heavy cable. End-cutting pliers probably have some real electrical value that has eluded us for many years, but they’re invaluable nail pullers and cutters.

Wrenches: A plethora of options

Carpentry work often involves minor plumbing work, primarily the temporary removal of piping connections for work such as installing cabinets and fishing Timmy’s pet hamster out of the garbage disposal. And all sorts of projects involve nuts and bolts and similar fasteners. Wrenches are the primary tool for this work.

An adjustable wrench is included in most basic tool kits because it accommodates any size nut — metric or standard — and small to moderate-size pipe fittings. On the downside, they don’t grip as well as fixed-sized wrenches. Even better quality ones are marginal, so don’t waste your money on a cheap pair. Get a good automotive-quality tool.

For a better grip, choose a wrench that’s sized for the fastener or fitting. Combination wrenches, which have one open and one closed (boxed) end, are sold in standard and metric sets and in sets that include both. Standard is still far more common in carpentry work, so buy a standard set first. For most carpentry work, you need only a small assortment (six to ten).

If you find that you run across metric bolts only a couple of times a year, save the cost of buying a set of metric wrenches by buying one of those self-sizing wrenches like the “Metwrench” sold at Sears stores and on TV infomercials.

For many projects, you can avoid the standard/metric debate altogether by purchasing a nice combination set of socket wrenches. Socket wrenches not only are sized for specific fasteners (which helps fight the age-old rounding-off-the-hex-head problem), but they also offer a ratcheted handle that enables you to tighten or loosen a nut without repositioning the tool every half-turn or so, as is required for combination wrenches.

Set screws, fittings, and other fasteners have hexagonal-shaped recesses that require an Allen wrench (also called a hex key or hex wrench ). These metal bars come in several shapes — straight, L-shaped, and T-shaped (where the top of the T is a handle). Although you can buy Allen wrenches individually — they may even come with a product that requires one for assembly, adjustment, or maintenance — it’s best to start with a matching set or two. On the rare occasion that you need one that’s not included in a set, buy it separately. Straight-wrench sets fold into a handle like a pocketknife. L- and T-shaped sets come in a plastic case or little pouch. The L-shaped ones are more versatile because the shorter leg of the L gets into places that the longer straight or T-shaped ones can’t.

Clamping and Gluing

Clamping is an essential part of many carpentry projects. Clamps hold your work in place while you tool the workpiece with saws, drills, sanders, and other tools. They also hold together two or more objects in precise alignment while you drill pilot holes and install fasteners. In the final stages, clamps hold things together while you wait for glue/adhesives to cure, in some cases reducing the number of fasteners required or eliminating the need for them altogether. The number of clamps a project requires varies widely, but typically, you need one every 8 inches or so along the joint.

Types of clamps

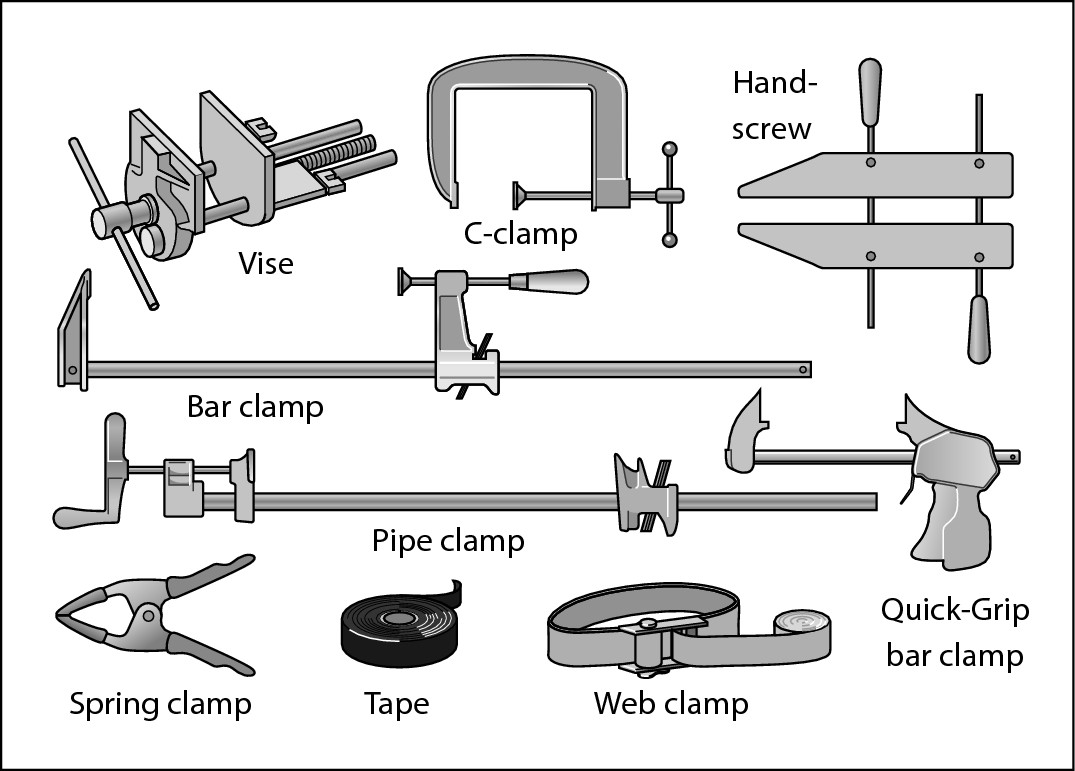

Because carpentry and woodworking projects assume an endless variety of shapes (flat, square, 90- and 45-degree corners, cylinders) and sizes (long, short, big, small), you need a variety of clamps and ones that offer versatil-ity. Dozens of types exist, but a few basic clamps have proven their worth. (See Figure 3-6.)

|

Figure 3-6: Get a grip with the right clamping tools. |

|

A C-clamp, named for its shape, comes in sizes that describe the maximum open capacity of the jaw, from 3/4 inch to 12 inches. It’s the primary clamp that woodworkers use. Most jobs require a minimum of two clamps, so make a practice of starting out with at least a pair of a particular size, and buy more as needed. C-clamps exert tremendous force: You never need to use anything other than your hand to tighten them. Prevent damage to your workpiece by placing a wood scrap between the clamp and the work. If they’re heavy enough, such boards also serve to distribute the force more evenly.

A C-clamp, named for its shape, comes in sizes that describe the maximum open capacity of the jaw, from 3/4 inch to 12 inches. It’s the primary clamp that woodworkers use. Most jobs require a minimum of two clamps, so make a practice of starting out with at least a pair of a particular size, and buy more as needed. C-clamps exert tremendous force: You never need to use anything other than your hand to tighten them. Prevent damage to your workpiece by placing a wood scrap between the clamp and the work. If they’re heavy enough, such boards also serve to distribute the force more evenly.

The edge C-clamp is a variation of the C-clamp. This clamp is designed to hold wood strips against the edge of another board, such as a plywood shelf or kitchen counter. To use it, lock the C onto the board and then tighten the edge screw against the edging strip.

The edge C-clamp is a variation of the C-clamp. This clamp is designed to hold wood strips against the edge of another board, such as a plywood shelf or kitchen counter. To use it, lock the C onto the board and then tighten the edge screw against the edging strip.

Pipe clamps consist of one fixed crank screw (head stock) and one movable jaw (tail stock) mounted on a pipe. The crank screw threads onto the end of the pipe, and the movable jaw slides over the pipe, locking onto the pipe when pressure is exerted. You can use any length pipe and easily move the clamps from one pipe to another to suit the project. Bar clamps

work like pipe clamps, but the bars aren’t interchangeable and therefore aren’t as versatile. Both types may be equipped with rubber pads to prevent them from damaging the work.

Pipe clamps consist of one fixed crank screw (head stock) and one movable jaw (tail stock) mounted on a pipe. The crank screw threads onto the end of the pipe, and the movable jaw slides over the pipe, locking onto the pipe when pressure is exerted. You can use any length pipe and easily move the clamps from one pipe to another to suit the project. Bar clamps

work like pipe clamps, but the bars aren’t interchangeable and therefore aren’t as versatile. Both types may be equipped with rubber pads to prevent them from damaging the work.

If you put all the movable jaws on one side of the workpiece, they tend to make the work bow up at the middle. Counter this tendency by alternating the clamps from one side to the other. If that doesn’t solve the problem, you can straighten a bowing surface by easing up on the clamp pressure just a bit, inserting a thick block of wood on the workpiece under the pipe at the midpoint, and tapping a shim between the block and the pipe. Check for straightness with the edge of a framing square or other straightedge.

If you need to use a pipe clamp for a nonrectangular workpiece, such as a round or triangular tabletop, cut a jig that, when clamped against the opposite edges of the work, yields a rectangular shape for the clamps to lock onto.

Spring clamps work like giant clothespins for quick clamping and releasing of projects where clamping is near the outer edge and the boards aren’t too thick.

Spring clamps work like giant clothespins for quick clamping and releasing of projects where clamping is near the outer edge and the boards aren’t too thick.

A handscrew has parallel wooden jaws that won’t damage wood workpieces as readily as a steel clamp. It exerts tremendous power with little effort on your part, but most important, it won’t apply twisting force, which tends to move your pieces out of alignment. The jaws also can adjust to accommodate work where the two faces are uneven or not parallel to each other.

A handscrew has parallel wooden jaws that won’t damage wood workpieces as readily as a steel clamp. It exerts tremendous power with little effort on your part, but most important, it won’t apply twisting force, which tends to move your pieces out of alignment. The jaws also can adjust to accommodate work where the two faces are uneven or not parallel to each other.

Web clamps wrap around irregular surfaces and exert inward pressure. Perhaps the most common application is gluing chair legs and the spindles that span between them. Loop the web around the work and thread it through a ratcheted metal fixture, much like you put a belt through its buckle. After you pull the band tight by hand, use a wrench or a large screwdriver to tighten the ratchet.

Web clamps wrap around irregular surfaces and exert inward pressure. Perhaps the most common application is gluing chair legs and the spindles that span between them. Loop the web around the work and thread it through a ratcheted metal fixture, much like you put a belt through its buckle. After you pull the band tight by hand, use a wrench or a large screwdriver to tighten the ratchet.

Real sticky stuff

If you’re using contact cement, the bond between the surfaces occurs — as the name suggests — on contact. Because of this bond, you must perfectly align the mating surfaces before you bring them together. Depending on the size and shape of the objects, try one of the following tricks to ensure correct alignment:

Rest the parts on a flat surface, with the bonding surfaces facing each other, and slide the pieces together. Doing so ensures that the bottom edges are in alignment. Tack a fence or guide to the worktable and keep the two pieces against both the guide and the tabletop as you slide. Then the two sides will be perfectly aligned.

Rest the parts on a flat surface, with the bonding surfaces facing each other, and slide the pieces together. Doing so ensures that the bottom edges are in alignment. Tack a fence or guide to the worktable and keep the two pieces against both the guide and the tabletop as you slide. Then the two sides will be perfectly aligned.

When the contact cement has dried sufficiently for bonding, lay dowels or other similar spacers on top of one piece. Then place the second piece on the dowels in proper alignment with the piece on the bottom. Then remove the dowels one at a time, allowing the glued faces to touch. With two boards, you may have just two or three dowels, depending on the length of the boards. For flexible material, such as plastic laminate or other veneers, you may need a dowel every 6 inches or so.

When the contact cement has dried sufficiently for bonding, lay dowels or other similar spacers on top of one piece. Then place the second piece on the dowels in proper alignment with the piece on the bottom. Then remove the dowels one at a time, allowing the glued faces to touch. With two boards, you may have just two or three dowels, depending on the length of the boards. For flexible material, such as plastic laminate or other veneers, you may need a dowel every 6 inches or so.

Sometimes, you can glue two objects together and then cut, plane, or sand both pieces simultaneously. This approach may eliminate any need for special care during assembly because you can correct any misalignment.

Sometimes, you can glue two objects together and then cut, plane, or sand both pieces simultaneously. This approach may eliminate any need for special care during assembly because you can correct any misalignment.

For more info on glue, see Chapter 2.

Guns for Pacifists

Caulk, adhesive, and glue are messy materials; whenever possible, it’s best that the containers that hold them also dispense them. Many such materials are available in squeezable containers, but sometimes dispensing tools (usually called guns of one sort or another) are required.

Hot-melt glue gun

No surprise here: A hot-melt glue gun does what its name suggests. Insert a stick of hard-cool glue in the back end, plug in the gun, wait for it to heat up, and squeeze the trigger. The trigger action forces the hard glue past the heating element, and out the nozzle comes burning-hot, melted glue.

.jpg)

Flip to Chapter 2 to find out when to use hot-melt glue.

Caulking gun

A caulking gun dispenses caulk and adhesives that are packaged in cardboard or plastic cartridges. The open-frame-style dispenser is easy to clean, but the most important feature to look for is a quick-release button on the back end. Press it with your thumb as you near the end of an application. If you have to fumble with an inconvenient or unreliable release system, adhesive will ooze out all over the place before you relieve the pressure.

You usually apply adhesive from a cartridge in straight ribbons, such as when you apply it to floor joists before installing plywood subfloor or to studs before hanging drywall. When using it on larger surfaces, such as on interior paneling that you’re installing over existing drywall, lay down squiggly lines. Just follow the installation instructions for the product.

Cut the tip of the cartridge at a 45-degree angle with a utility knife. How much you cut off depends on how wide a bead you want, but keep in mind that you can always cut off a little more if the bead is too small. You’re stuck with wider beads if you cut off too much.