It’s remarkable to think that just twenty years ago there were few common terms (most of which I either made up or filched from different sources) for even the most basic elements of an anchor, and there were even fewer standard protocols about how to build them. We venture into this new edition with most of the terms now known and used by all and with the basic protocols established and refined by millions of climbers in many lands.

And yet the majority of our anchoring techniques are provisional, not absolute. Furthermore, there are often trade-offs in choosing one technique over another. Lastly, while we’d like each anchor to conform to a wide-ranging evaluation criteria called SRENE (Solid, meaning the anchor is set in solid rock rather than crumbly choss, Redundant, Equalized, and No Extension), it’s the rare anchor that can accomplish this even close to 100 percent. If we could suggest a few protocols that would absolutely work in absolutely every situation, I could write this book in fifty pages. Instead it will take us five times as long to grasp an exceedingly fluid subject. Climbing anchors are largely a matter of compromises; the trick is developing a feel for what you should and should not compromise at a given place on the rock.

Of course the task of compiling a definitive text on anchors will always be lacking because of the inexhaustible variables found on the rock. There are also dozens of methods and as many ideas about how to execute most all the basic anchoring procedures. If we were to include even a fraction of these, this book would run a thousand pages long. While the material in this book is, strictly speaking, nothing more than our experiential opinion about a broad-reaching subject, that opinion has drawn heavily from manufacturers, instructors, guides, and leading climbers in the United States and beyond. Heeding current refinements and wrangling it all into one standardized modus operandi is the mission of this book. And the starting point for all of this is the philosophy underlying the entire subject of climbing anchors.

The great conundrum about the anchors has always been the same: What does “secure” actually mean? Or more accurately, what should “secure” mean? Not in a theoretical sense, but in the sense in which a real climber will confront a real situation on a real rock and must make decisions that will keep her alive. Without “cliff sense” and acceptance that skilled climbing is efficient climbing, some people consider the subject in terms of absolutes. “Secure” will then be defined and defended from a position of neurotic fear, resulting in needless overkill in the quest to achieve the impossible goal of absolute safety. Such thinking, if applied to freeway driving, would lead us all to rumble down the road in Abrams tanks. But it’s impractical to do so, so most of us are fine with driving a car with some— though not absolute—protective qualities. Yet as any experienced driver will tell you, the key to avoiding accidents is not to drive a tank, but to stay on the ball and avoid risky maneuvers.

Instead of improving one’s wherewithal on the cliff side, gym-trained sport-climbing has introduced a brand of climber prone to believe safety comes from the equipment and the systems themselves, instead of how these are used. This expectation can never be realized in the field. Secure climbing remains the product of experience, knowledge, judgment, and common sense, as opposed to the gear you employ. Our gear and our methods must be “good enough,” but unless we can accept that “good enough” can never be an absolute, we’ll keep looking for the climbing equivalent of that Abrams tank. Not only will we never find it, but we’ll also waste everyone’s time overbuilding anchors and exasperating our partners with specious arguments chasing the unreachable goal of total safety.

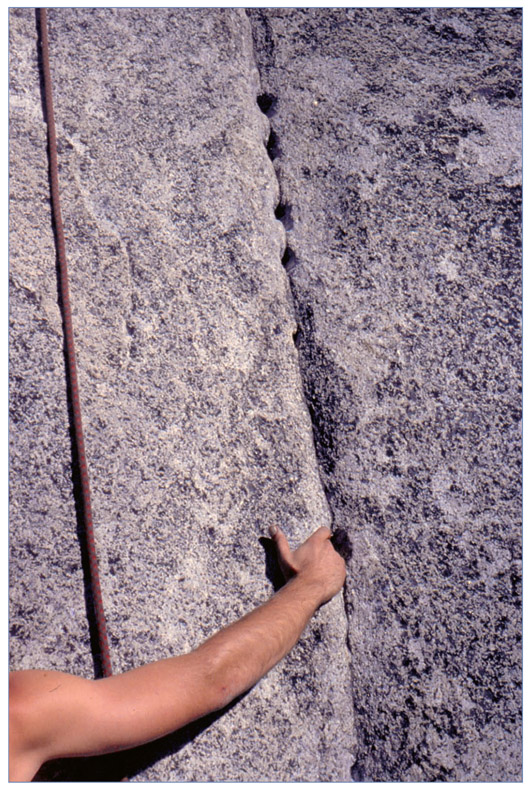

ANDREW BURR

In practical terms, “better” means “stronger” only if what you have is not “strong enough.”

Remember . . .

• A stronger belay anchor is not necessarily a better anchor.

• Climbing gear rarely breaks, but it often pulls out.

• Even the strongest primary placements are worthless unless they are securely unified into the roped safety system.

• Protection and the belay anchor work in tandem with judgment, experience, and belaying and climbing skill.

Hidetaka Suzuki finger jamming on The Phoenix, Yosemite, California.

“Good enough” means an anchor that will unquestionably hold the greatest forces a climbing team can place upon it. Additionally, every experienced climber factors in a safety margin of at least one fold, meaning the anchor is built to withstand at least twice as much impact as that generated by a factor 2 fall (explained later). “Good enough” does not mean an anchor capable of holding a celestial body, which has forces you can never generate on a rock climb. An anchor that can hold Neptune in orbit is not “better” than a “good enough” anchor because the former is safeguarding against purely imaginary forces. And we should know that even this advice is impossible to follow at least some of the time. It’s likely that at some point you will find yourself hanging from anchors you pray to God are good enough, while knowing that they are probably not. Once you start up a rock wall, there are no guarantees.

In short, this manual is geared to provide tangible, specific, comprehensive, and user-friendly information to climbers who are learning how to place protection and who arrive at the end of a pitch and have to construct an anchor to safeguard their lives. As Canadian big-wall icon Hugh Burton stated, “Without a bombproof anchor you have nothing.” The importance of sound anchors cannot be overstated.

Basic Anchor Building Facts

That much said, protection and the belay anchor are only parts of a hazard-mitigating system that works in tandem with judgment, experience, and belaying and climbing skill to protect the team from the potential dangers of falling. Here risk evaluation can only be broached in terms of placements (protection or “pro”) and anchors; the rest falls under leading skills, which is a separate study imperative for all aspiring climbers.

Clearly, the starting point of any anchor is setting bombproof primary placements. The means rigging, by which you connect the various components into an anchor matrix, should never be relied upon to provide the needed strength not found in the primary, individual placements. Furthermore, the goal is not simply strength, but security. More on this later.

Two common misconceptions arising from previous editions are A) if the anchor met the SRENE criteria, then it was automatically secure and fail-safe; and B) any anchor that did not meet the criteria was, without exception, a liability, as was the climber who placed it. Reality does not support either notion. There are far too many accounts of well-rigged anchors that failed for the simple reason that SRENE criteria cannot compensate for bad primary placements (again, bombproof placements remain the backbone of all sound anchors).

SRENE Anchors

• Solid

• Redundant

• Equalized

• No Extension

The fact is, even SRENE criteria cannot be met in absolute terms. No anchor is ever perfectly equalized; a well-equalized anchor commonly has some possibility of “extension” if one component in the anchor matrix fails; and few anchors feature textbook redundancy. The true value of SRENE is for use as an evaluation strategy, not as some ideal anchoring model you can and should attain. But even if someone, somewhere could build perfect SRENE anchors, we could never apply the criteria across the board and believe we had the danger licked. Though I would not recommend anyone violating the SRENE code, there are anchors out there that do not conform to SRENE, and yet these anchors are literally capable of holding a car.

Key SRENE Points

The basic concerns just discussed provide the basis for much of the material that follows. The mission of this guide is to provide the following:

• A simple, basic philosophy that guides the entire process

• A set of general, tangible motifs and rules-of-thumb to focus the overall process

• The general themes clarified through text, side-bars, and specific examples via pictures, illustrations, and breakdowns

Practical value remains the guiding principle of this manual. There’s no getting around the fact that this is a textbook, technical by nature. I’m not writing it for fun or amusement (though I hope some might find parts of the text amusing), and my impulse to make it flow like a short story has been sacrificed in an effort toward thoroughness. The sheer volume of information can sometimes overwhelm the beginner. Although the many side-bars break down each key topic into simple bullet points, there’s still no getting around doing some heavy lifting to get through the material, especially if the subject is somewhat new to you.

There are many topics more involved and complex than climbing anchors, but few where the concepts are so rigorously applied, and where slipshod workmanship can so quickly make you dead. This is the main reason to take your time with this material. We’ve all crammed for exams, then later walked from the classroom with all that we “knew” pouring from our beans like flour from a sieve. The material herein can never be absolutely mastered. Once you absorb the basic concepts, it comes down to experience and judgment, qualities that come in their own timeor not. Rock climbing is not for everyone, especially adventure or “trad” climbing, for which this guide is especially germane. Building anchors is a lifelong study, so pace yourself, and live long.

When Building Anchors, Always Remember . . .

If a modern-day rock climber could time-travel back forty years to the halcyon days in Yosemite, she would see equipment and techniques that few remember and fewer still ever used. Back then, boots, or Kletterschues, were more like clodhoppers, with their stiff uppers and rock-hard cleated soles. Ropes were adequate, but not nearly as versatile and durable as the modern article. Protecting the lead was a business of slugging home pitons and slinging the odd horn. Artificial chockstones (nuts) were available, but most were weird, funky widgets with limited utility. Save for really bombproof placements, these first nuts were far less reliable than pitons for securing the rope to the cliff.

In 1970 most nuts were European imports. The best came from England, where they were invented. Initially American climbers were suspicious of nuts, and most everyone considered them unacceptable as a general replacement for pitons. Clearly they weren’t as sound, and anyone making a hard sell for their use in the United States was thought to be a daredevil.

Things changed suddenly. In the early 1970s John Stannard wrote a seminal article illustrating how pitons were rapidly demolishing the rock, followed closely by Doug Robinson’s “The Whole Natural Art of Protection,” which appeared in Chouinard Equipment’s 1972 catalog. Royal Robbins also suggested nuts as the only alternative if the crags were to survive aesthetically. By this time, Chouinard Equipment (now Black Diamond) was mass-producing chocks, and almost overnight “clean climbing” became the rage. First “clean” ascents of popular big walls became fashionable. Climbers waxed poetic about “artful nutting” and “fair-means” climbing. By 1973 walking up to a free-climbing crag with hammer and pegs was akin to showing up at an Earth First! festival in a bearskin coat.

It is a wonderful thing that the climbing community was quickly won over to clean climbing. The sport was booming, and every classic climb was destined to become a ghastly string of piton scars unless nuts replaced pitons as the common means of protection. Within a couple of seasons, clean climbing had reduced a climber’s impact on the rock to chalk and boot marks. The benefits were clear, and the change was long overdue.

Unfortunately, the nuts available at the time still had serious limitations. Chouinard Equipment’s Stoppers and Hexentrics (Hexentrics appeared in ’71, Stoppers in ’72) were pretty much the whole shooting match, though one could flesh out a rack with oddball European imports that did little more than take up room on the sling.

Recall that in the ’70s, American climbing standards came principally from Yosemite, where cracks are generally smooth and uniform. The Stoppers worked well in cracks that were ultrathin up to an inch in width, but the first hexes (a name later adopted by other manufacturers and now used as a generic term) needed a virtual bottleneck for a fail-safe placement. On long, pumping Yosemite cracks, such constrictions often are few and far between, if present at all. From about 1971 to 1973, old test pieces became feared again—not so much for technical difficulties but because of the lack of protection provided by available nuts. There were a handful of routes where you simply couldn’t fall, though more than one climber did, and the scenes were not pretty. Clearly the limitations of these first nuts, coupled with climbing’s rising standards, made clean climbing on hard routes a bold prospect during that first phase of the hammerless era.

Nuts from the early 1970s.

Then in late 1973, Chouinard changed the symmetry of the hexentric, eliminating the radical taper. The resultant “polycentric” was a nut one could place in four different attitudes (including endwise), and each placement was far more effective than what could be achieved with the old design. These new hexes hinted at the camming to come and brought a degree of security back to the sport.

Subtle changes also were appearing in other chocks. Wire cable replaced rope and sling for the smaller-size nuts. Manufacturers entered the market with specialized gear—brass nuts, steel nuts, even plastic nuts were available for a short time. New-fangled homemade gear also began appearing, and the race was on for more diverse designs.

The pivotal breakthrough came in 1978, when Friends first became available commercially. The popular story is that Friends evolved from a simple camming device invented by Mike and Greg Lowe in 1967. Ray Jardine, a climber with a background in aerospace engineering, spent much of the ’70s refining the concept (the Lowes had the right concept but never produced a workable design), and the first spring-loaded camming device (SLCD) was the result. The era of super-specialized protection had finally arrived, and a protection revolution followed. In the ensuing ten years, SLCDs—more commonly called camming devices, or cams— became available from many manufacturers in various forms and sizes. Also component “sliding nuts” appeared that literally expanded in breadth when weighted in the direction of pull (explained in detail later). Sliding nuts never truly caught on, possibly because they were often difficult to remove.

As other companies sprang up and European companies airmailed ingenious, sometimes kooky contraptions into the American market, passive nuts were steadily improved and customized for specific applications. Sling materials likewise evolved, as did carabiner design and rope technology. Present-day novelties include the DMM revolver carabiner, with a built-in pulley, and the removable bolts now available from Climb Tech, to mention only a few. Yet since the SLCD first arrived on the scene in 1978, there hasn’t been any comparable breakthrough in protection technology. Refinements continue with every aspect of climbing tackle. Classic designs are regularly tweaked and buffed and reworked to effective ends. Cams themselves have undergone significant change, with some designs now offering greatly increased range of place ment. But the Next Great Thing has yet to appear.

All told, the current state of rock-climbing equipment makes memories of barrel-chested bruisers in lug-sole boots slugging home pitons almost quaint. To catalog all the viable equipment manufacturers would involve adding fifty pages to this guide. Simply understand there is fierce competition for your dollar, and to get it, companies are sparing nothing in both technology and research and development. The result is gear superior to most any other adventure sport.

Pin scars on Serenity Crack, Yosemite.