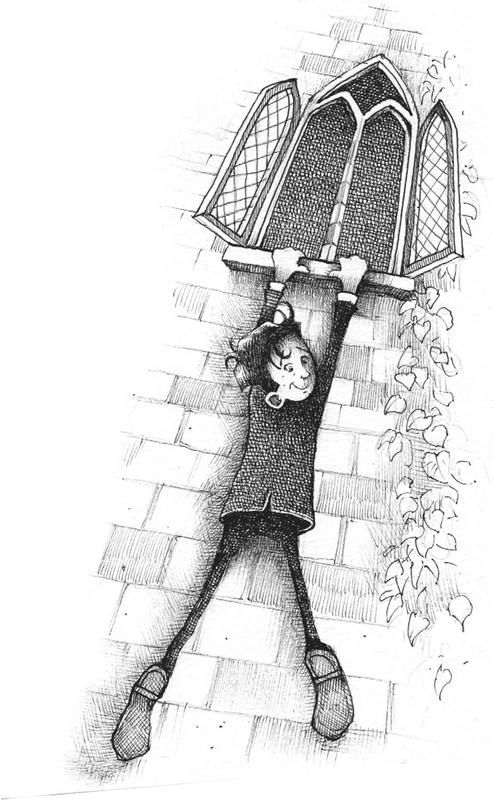

The first time I saw Henry Hunter he was hanging by his fingertips from the window sill of the headmaster’s study.

He looked down as I walked past, fixing me with his large, slightly protuberant blue eyes and said, “Could you spare a moment, old chap?” (Yes, he really does talk like that.)

I wasn’t really sure whether to answer or just ignore the boy dangling from the window. You see, I hadn’t been at St Grimbold’s School for Extraordinary Boys very long, and wasn’t sure of the protocol in such an event. But he did look as though he might fall at any moment.

“Um, can I help?” I asked.

“Well, could you be a good fellow and fetch the ladder from the gardener’s shed?” said Henry, beaming at me.

The gardener’s shed was just a short walk away, but since the situation seemed to call for it I ran all the way there and back. I leaned the ladder against the wall, angling it close enough for Henry to reach with his feet and climb down.

“Thanks!” he said rather breathlessly. Then he nodded towards the window of the headmaster’s study and added, “You might be better off not hanging around here for a while.”

“Okay… right… thanks,” I said, wondering what I was thanking him for. I found myself following Henry as he walked quickly away across the playing fields. He headed towards the elm trees which lined the drive up to the imposing cast-iron school gates.

I caught up with Henry and noticed he had a bundle of bright green cloth tucked into the front of his school blazer.

“So – um – what were you doing up there, anyway?” I ventured. I didn’t normally ask such direct questions, but somehow I knew the answer would be too intriguing to ignore.

Henry turned his bright blue eyes on me. “I’m not sure you’d believe me if I told you,” he said.

“Try me,” I answered. I was becoming fascinated by Henry’s odd behaviour and manner of speech.

“Okay,” said Henry. He looked around to make sure no one was watching, then pulled the mysterious bundle from his jacket, unwrapping the fabric at the edge for me to see what was inside. It looked a bit like a flute – but not the kind likely to be played in a school orchestra. This one was elaborately carved out of what looked like old bone (not, I hoped, human – but you never know).

I didn’t know what to say. “I-I’ve never seen anything like it before!” I stuttered.

“That’s not surprising,” said Henry, pushing back his slightly floppy hair, “because it’s one of a kind. Anyone who listens to it has to do whatever the person blowing it says! I didn’t think it was the sort of thing Dr Hossenfeffer should be in charge of.”

There it was. The sort of casual remark I would become very familiar with as I got to know Henry Hunter better. The sort that showed that he, a twelve-year-old (even in a school for extraordinary boys), thought nothing of challenging the headmaster. I’d soon discover that it was the kind of thing Henry Hunter did all the time.

Henry explained that Dr Hossenfeffer, the current headmaster of St Grimbold’s, had stolen the strange flute from a passing Himalayan priest. I suspect his reason may have had something to do with trying to control a hundred and fifty unusual boys. But in any case Henry had decided it was far too powerful an object to be in the hands of an ordinary schoolmaster – especially one who was supposed to be looking after us. So he’d picked the lock of Professor Hossenfeffer’s study, cracked the seven codes required to open the headmaster’s strongbox, taken the flute and was just about to leave when he heard the old boy coming. That’s when he climbed out of the window and found he was stuck. I came along and the rest, as they say, is history.

After the whole dangling-from-the-window-ledge event Henry and I became best friends. Although I’m still not quite sure why. Maybe it’s because every hero needs a sidekick – or at least someone to tell the story of their adventures. Since then, Henry has said to me on more than one occasion: “Every Sherlock Holmes needs his Watson, Dolf, and you are mine.”

At first, I thought this wasn’t very flattering – everyone knows Dr Watson isn’t the sharpest knife in the box – but I soon came to realise that almost no one is as bright as Henry Hunter, so I decided I could live with the comparison.

A few days after the incident of the flute, Henry came up to me in the quad and said in his rather high and nasal voice, “You’re Adolphus Pringle, aren’t you?”

I nodded, a bit surprised he knew my name – I hadn’t mentioned it during the window-sill rescue.

“I just wanted to thank you for helping me out of that spot of bother the other day,” Henry said, flashing me a toothy grin.

“You’re welcome,” I told him. “It was no problem.”

Henry and I stood in the corner of the quad, quiet for a moment – one of those rather awkward silences that sometimes happen when no one can think of what to say next.

Then Henry grinned again and said, “Listen, I’m just off to look for this rare bug. Like to come along?”

Looking back, I don’t know whether he really wanted me to come along or if it was just something to say, but that didn’t occur to me then and I jumped at the opportunity of doing something other than school lessons or homework. Of course he neglected to tell me that the bug he was looking for was a metre long and found only in the jungles of Africa, but that was Henry for you. I also didn’t know he’d chartered a Learjet, hired some local natives as guides, and that he was carrying a £30,000 video camera with which he intended to capture the bug on film.

As we tore through the skies at 50,000 feet in the Learjet, Henry explained that everything strange about his life began with his name. Having the surname Hunter got him interested in hunting for things – but not for just anything, like a great new sandwich or a book by his favourite author – but BIG THINGS, like legendary creatures and items that no one believed in, such as aliens, yeti, the Holy Grail, mummies, and the crown of Alexander the Great. At first it meant looking stuff up in books (Henry always did that instead of using the internet – which he said made you lazy) but in time he graduated to mounting actual expeditions in search of particular things.

He could afford to do this, and things like hiring the Lear, because his parents were rich – his dad had, years ago, invented the Cronos microchip, which revolutionised the gaming industry by making it possible for gamers to interact with their favourite characters more closely than ever before. Then he’d created the Cronopticon (voted Best Games Machine Ever for several years running) and after that the Cronopticon 2, the Cronopticon Gigantic and the Cronopticon Mini – until just about everyone in the world owned one or other of his consoles. His dad was clever – but not as clever as Henry who, by the time he was ten, had degrees in subjects most people have never even heard of. Astrophysics, lepidoptery and callisthenics are some of the ones I can remember.

Henry also told me that he could disappear on adventures like this because his parents weren’t around. His mother had suddenly got a bad attack of responsibility and decided that she and her husband should put their billions to good use. They were off in search of a particularly rare orchid, which it was rumoured could cure half the diseases in the world. At first they came home every month or so to see Henry, but after a bit all he saw of them was an occasional email and a video call on his birthday and at Christmas.

So that was how Henry had ended up at St Grimbold’s, which may sound a bit tough on him, but he said he liked having parents who were off doing something useful and exciting – and it meant he had the kind of freedom no one gets when they’re twelve.

I didn’t have much of an opportunity to tell Henry about my background. Which is just as well, because I’m not super-bright, and I don’t have an upper-class accent or designer clothes or any of that stuff. I just happen not to fit too well in the kind of school that insists on homework, the right kind of gym bag and shirts properly tucked in. My last headteacher told me, “Pringle, you have an overactive imagination. It is not welcome here.” Luckily St Grimbold’s has a trust fund to offer scholarships to kids like me, who are reasonably smart but whose parents are anything but rich, to get ‘a proper education’, as my dad calls it.

The Hunters were another matter; they forked over a pretty hefty sum to get Henry into St Grimbold’s, and made it a lot easier for Henry to indulge in his hobby.

You name it: Henry hunted it.

And most of the time, I was with him.

The rare bug adventure was actually pretty ordinary compared to some we’ve had since, though we did encounter a group of hunters who were just as keen as Henry to find the bug, and who were prepared to do anything to stop us. But, thanks to Henry’s amazing skill and encyclopaedic knowledge of lepidoptera, we managed to escape, and film the giant bug, without getting killed. But that’s a story for another time.

For now, I want to start with a different adventure, one that’s more important for you to know about. A story that still gives me goosebumps. Not The Story of the Great Lizard of Jambalaya, or The Adventure of the Curried Frogs. It’s one from Henry’s files, an adventure that I think might contain some vital clues that I need rather badly. Of course I was there, so I know what happened, but, dear reader, I need your help.

So please keep your eyes peeled, your ear to the ground, your mouth wide. Because this is the first of…