Three

WAR AND PROSPERITY

World War I, for all its tragedies, brought prosperity to the Glendale area. The price of agricultural products soared. Cotton, especially, became a favorite crop; at one time it sold for $2 per pound. Perishable crops—melons, lettuce, and so forth—were also in high demand, and shipping them kept the Glendale Ice Company (later, Crystal Ice Company) busy icing the rail cars that carried the produce east and west. It was not just farmers who prospered. The whole area was seeing boom times and the creation of new businesses such as the Pacific Creamery and the Southwest Flour and Feed Company.

After the war, although slack times for some farmers, Glendale continued to move forward. By 1920, the population had swelled to 2,700, almost three times what it was 10 years earlier. More people meant more housing, which meant that suppliers of building materials and workmen to assemble them were kept busy. In downtown Glendale, many of the ever-popular bungalow-style homes were built in the Catlin Court residential area. Many downtown streets were paved, including Grand Avenue. Streets were renamed and numbered to post office specifications for free mail delivery in town. The high school was regularly graduating some two dozen students, new churches were gaining a foothold, and lodges and civic organizations were flourishing. The new U. S. Government Poultry Experimental Farm was set up south of town, and the whole town celebrated “Chicken Day” in honor of Glendale’s poultry businesses.

Baseball was the popular entertainment, especially when winning teams were fielded. Glendale’s second newspaper, the Saturday Shopper, was first published. And in 1928, to the delight of the whole town, Glendale’s first swimming pool, the Silver Pool, opened to the public. The focus of business was, as it always had been, the streets close to the town park (now Murphy Park). Among other businesses around the park were a hardware store, two dry-goods stores, five markets, a movie theater, and a real estate company.

In the 1930s, a new library was built in the park, and nearby a second grammar school was started. By mid-decade, after the repeal of Prohibition, alcohol-free Glendale permitted the sale of alcoholic beverages. The annual Mexican Independence Day fiesta continued to be a popular fall event, and dial telephones arrived in 1937. By 1940, Glendale’s population had grown to 4,869.

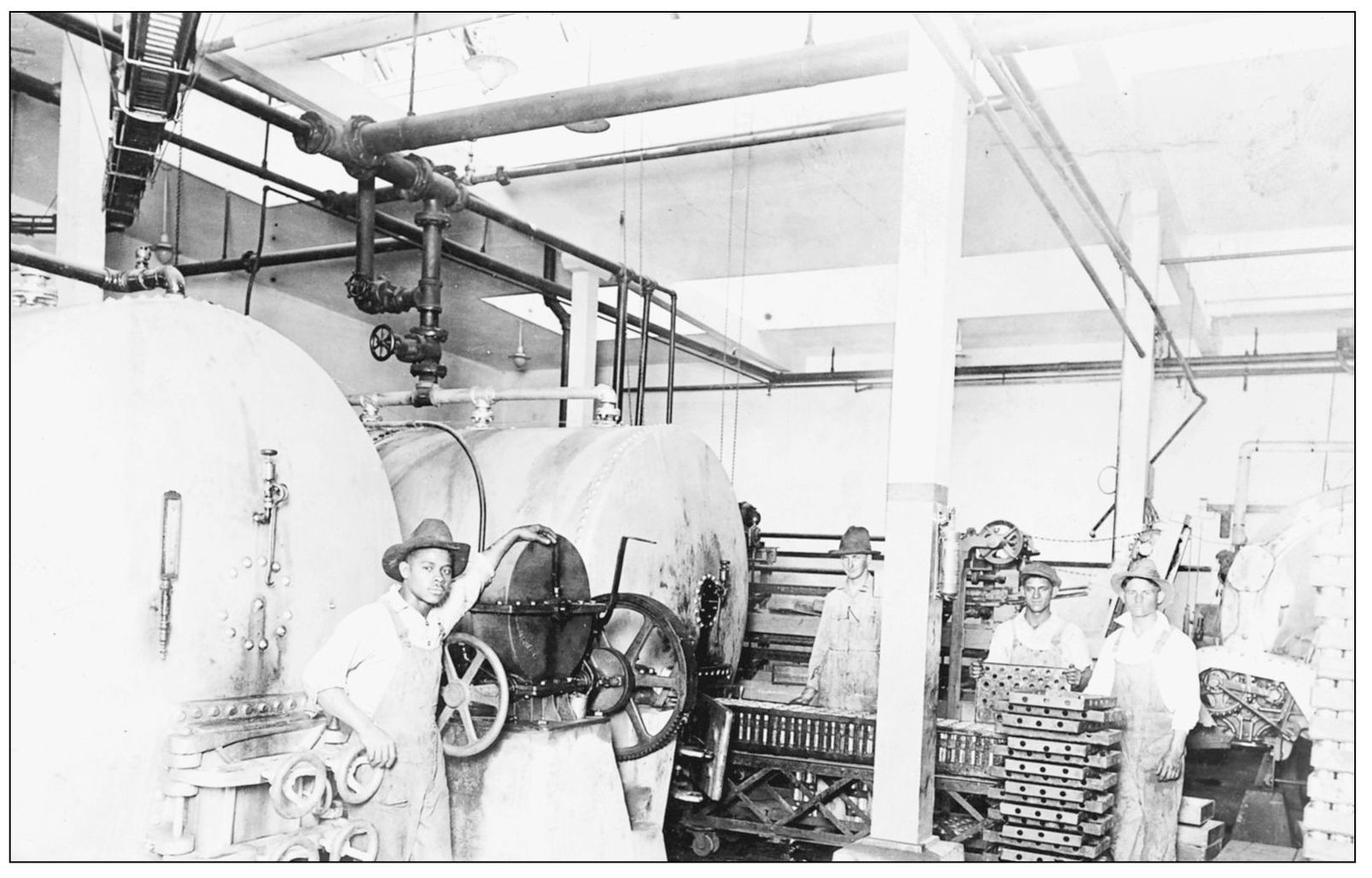

Construction of the Pacific Creamery Company’s milk-condensing plant, half a mile southeast of town, nears completion in 1916 (above). The plant was built in response to soaring milk production during World War I, and it cost more than $400,000 to complete. Its main product was “Armour” brand canned milk. Falling prices for milk after the war brought a decline in the dairy industry, and as a result, the company closed its milk-processing operations in 1920. The plant was reopened as Webster’s Associated Dairy Products Company in 1933 under the ownership of Dudley B. Webster. It operated under two other owners until 1971, when it was closed for good. A look inside the Pacific Creamery Company plant in 1917 (below) reveals a complex array of equipment.

By winning five of six stipulated games in 1916, the high-school boys’ baseball team, the Sugar Kings, were lionized as champions. The girls’ softball team, the Sugar Queens, also had a winning season. They won two of the three games (all against the Indian School team) they played, so they proclaimed themselves champions. The 1916 team consisted of Julia Campbell, pitcher; Vida Roberts, catcher; Frances Green, first base; Gail Campbell, second base; W. Long, shortstop; Ruth Forney, third base; Hazel Spillman, outfield; W. Champie, outfield; and Marguerette Brooks, outfield.

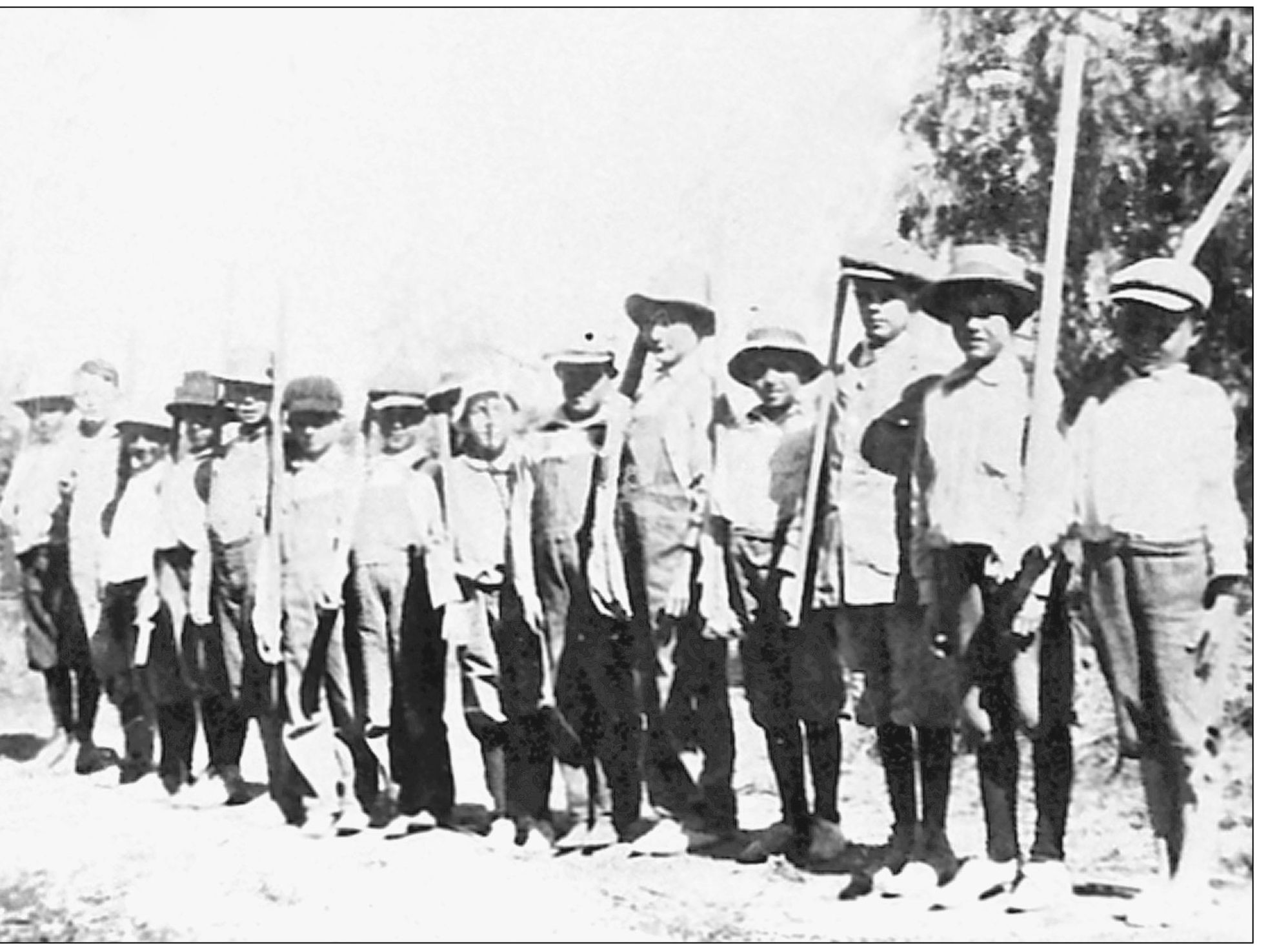

During World War I, Glendale residents bought Liberty Loan Bonds, raised extra crops, and supported the war effort in other ways. Children, as well as adults, found ways to show their patriotism during the war. Youngsters dressed in doughboy attire would routinely defeat the “Hun” on their homemade battlefields. An especially desirable accoutrement, if a boy had one, was a broad-brimmed, military-appearing hat. Toy airplanes were also popular for playing at war. Even though there was no threat of attack in Arizona, these neighborhood boys were prepared with sticks and pretend rifles to defend the home front in 1917.

In support of the war effort in 1917, Glendale residents observed meatless days, raised “victory gardens,” bought War Savings Stamps, and joined in parades to stimulate war awareness on the home front. This float was built on a Fitch four-wheel drive tractor, which is pulling a hay wagon. The Masons, Eastern Star, and Fitch agents Fred Walsh and Charles Juncker sponsored the float. Juncker, a local blacksmith, is second from right, and Bill Coffelt, his apprentice, is on the right. The other two men are unidentified. A short time after this parade to “Help Feed the Boys Over There,” Coffelt joined the Marines and went to Washington state for basic training, and Juncker went to work in a shipyard in San Francisco for several months.

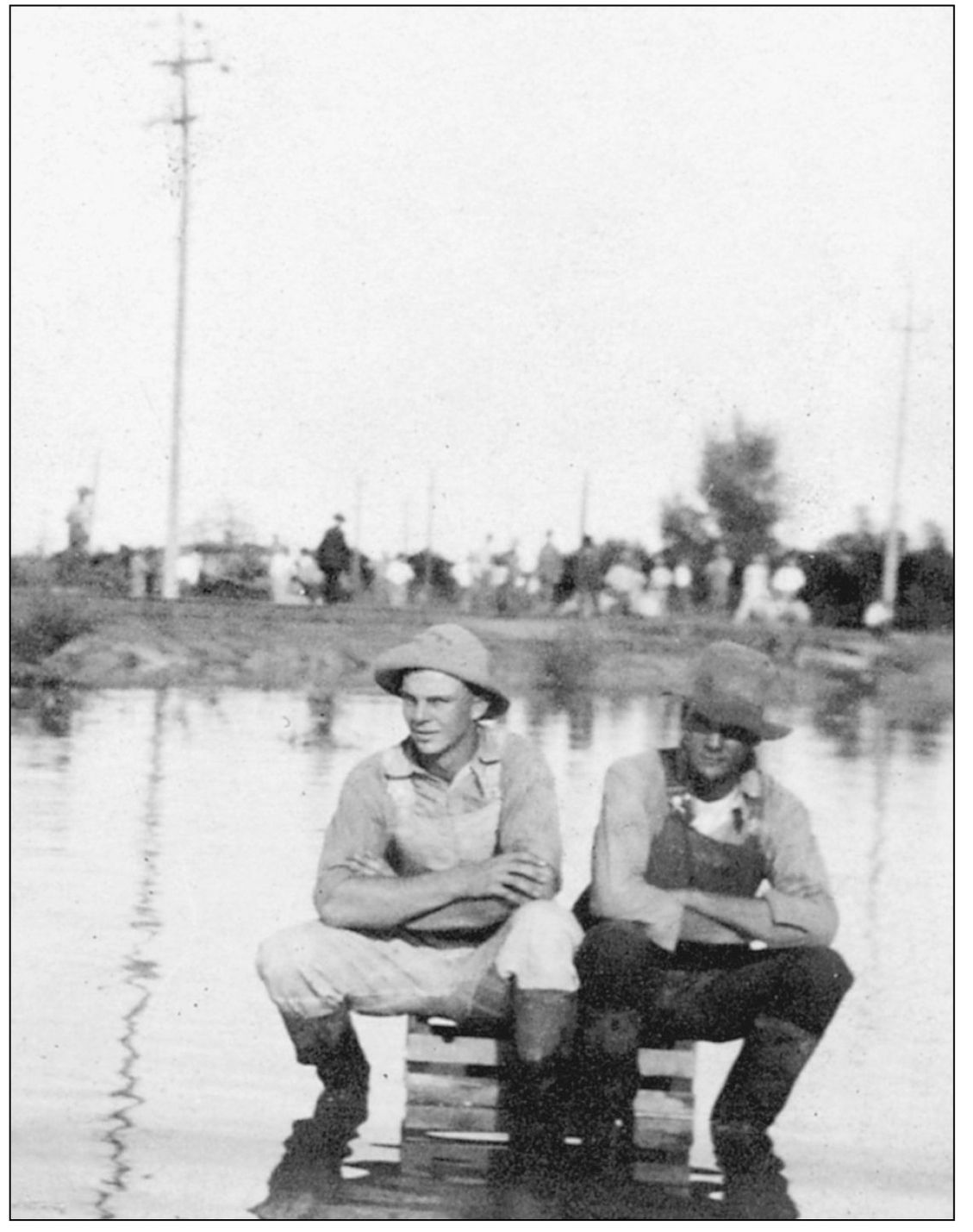

The most severe wind and rainstorm in Glendale for years, according to the Glendale News, occurred the evening of July 26, 1917. In the flooded aftermath, everyone pitched in to sandbag merchants’ shops and repair a washout of the railroad grade. Pictured at left, two local boys, Charlie Pitts (left) and Walter Grassie, worked as hard as anyone, but they took time out to have their picture taken while sitting in the middle of flooded Grand Avenue. Behind them is the railroad grade that was breached by the floodwaters. The image below is of the first engine across the repaired washout. The repair is visible below the rear wheel of the engine. Several months after this flood, Grassie died while serving in World War I.

As far as the farmers of Glendale were concerned, the most important businesses in town were the blacksmith shops. They made it possible to keep equipment in good repair and workhorses shod, which were critical needs at the times of seeding, harvesting, and marketing. Founded in 1911, Charles Juncker’s Blacksmith and Machine Shop was the most modern it could be. In 1919, he advertised that all of his saws, drills, emery sanders, planers, and forges were operated by electric-motor attachments. Juncker, of course, did the usual sort of work common to blacksmiths, but he also repaired and rebuilt automobiles and sold new tractors. The shop was especially known for its custom building of such farm equipment as hay derricks, rakes, wagons, and other farm machinery. The shop workers are, from left to right, Charles Juncker, Bill Coffelt, and an unidentified apprentice.

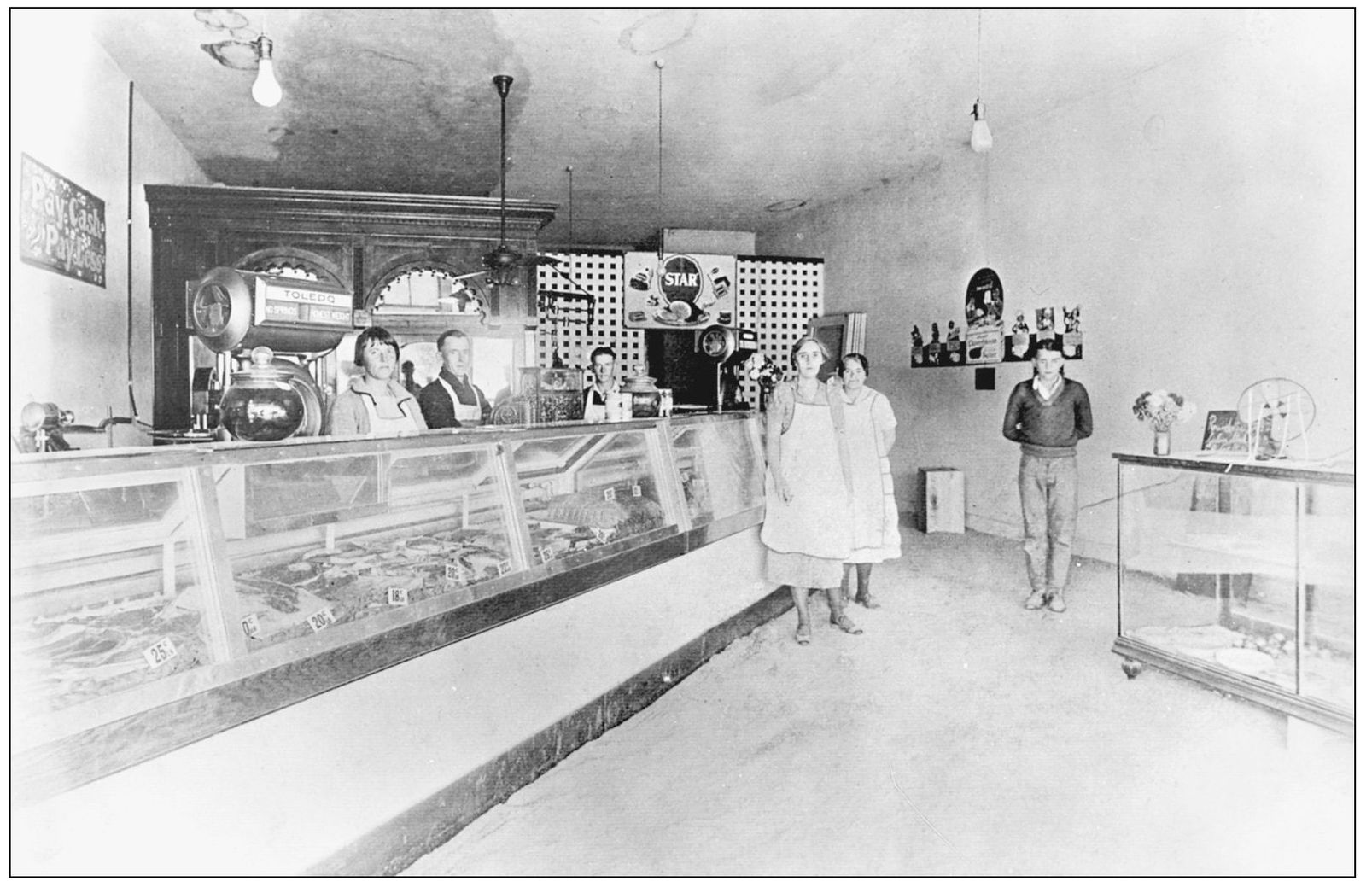

For a few years, beginning in January 1918, the Tharpe Building (above) on the corner of Washington Street (Glendale Avenue) and Second Avenue (Fifty-eighth Avenue) housed the U.S. post office in the corner of the building. After World War I, down the street on the far right, soldiers used one room to meet as they attempted to organize an American Legion post. Next door to the post office on the north (above, left) was the Post Office Meat Market (below), owned by Bessie and Ray Stockham. The sign on the wall of the meat market proclaims, “Pay Cash and Pay Less.” North of the market was the Pantatorium, a dry-cleaning establishment.

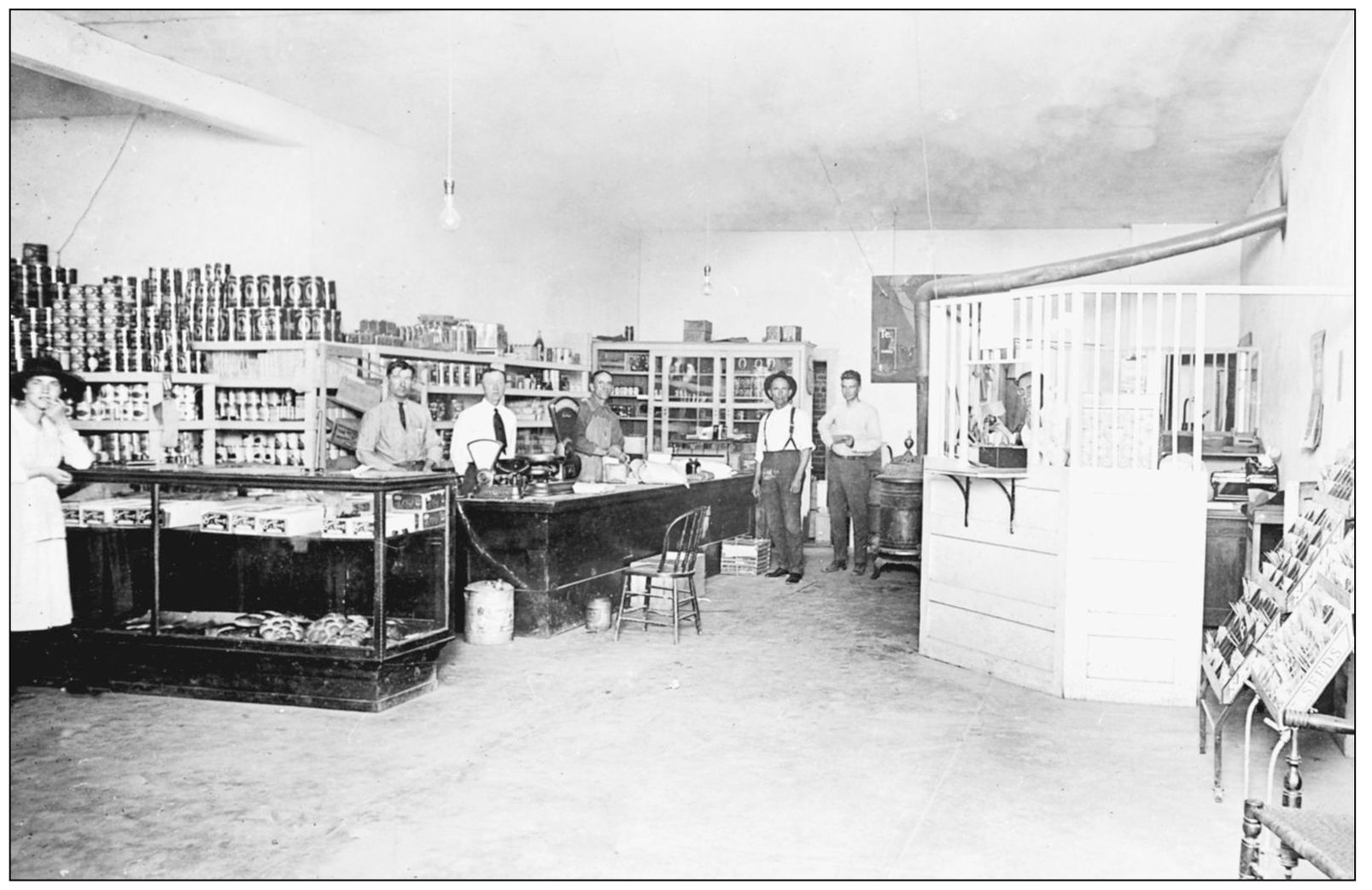

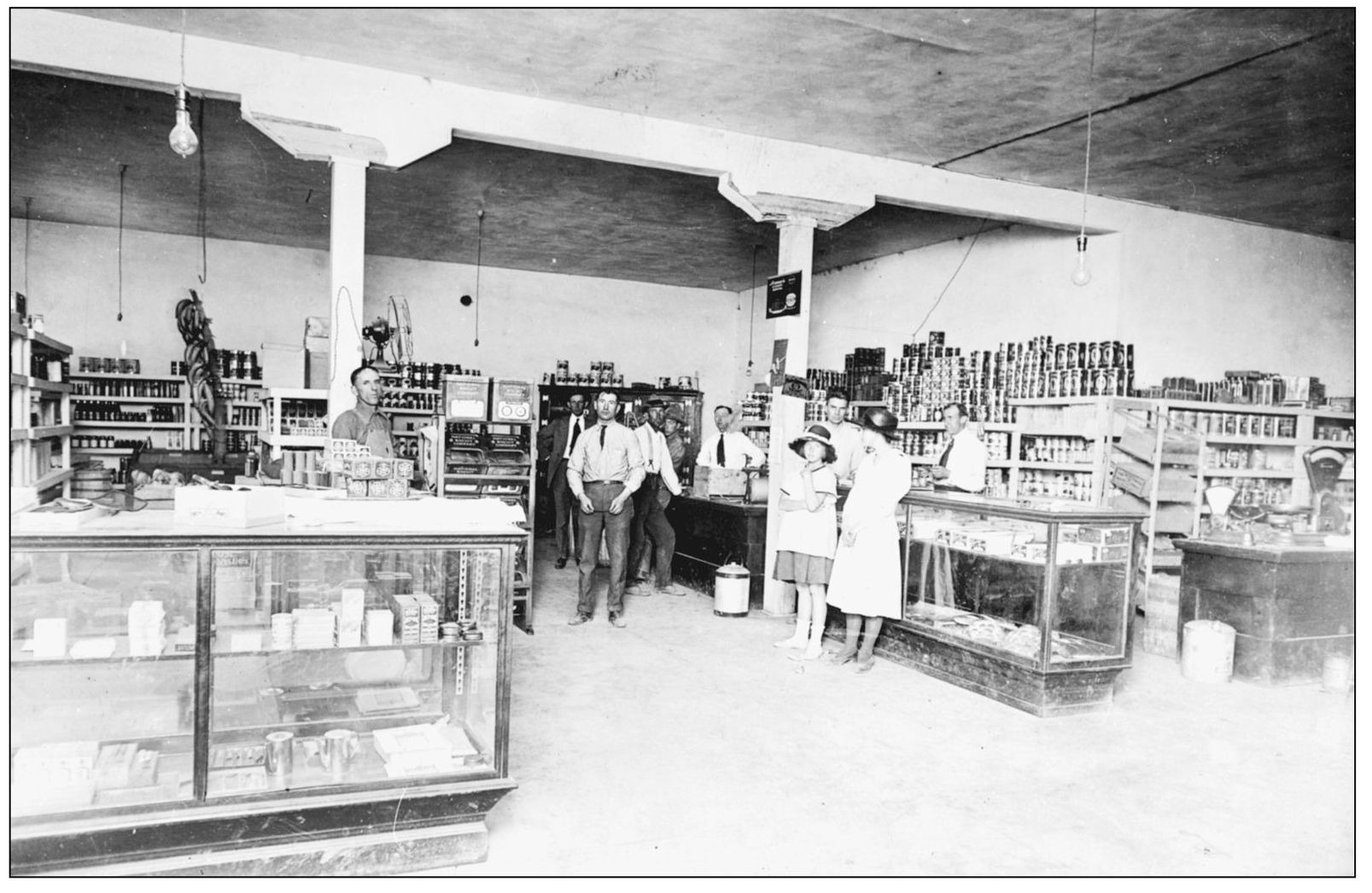

Kitty-corner from the town park in 1919 was Beaty’s Market, which carried “staple and fancy groceries; fresh fruits and vegetables brought in daily; and butter and eggs.” The bookkeeper’s cubicle on the right (above) is where items were purchased or added to the buyer’s account. Besides the usual market goods, James R. Beaty carried home-canned products bartered from customers. Note jars of home-canned food on the shelves at the back of the store (below). Beaty also took in trade, as was common practice in those days, eggs, butter, fruits, and vegetables. The rooms above the market were used as a hotel for several years.

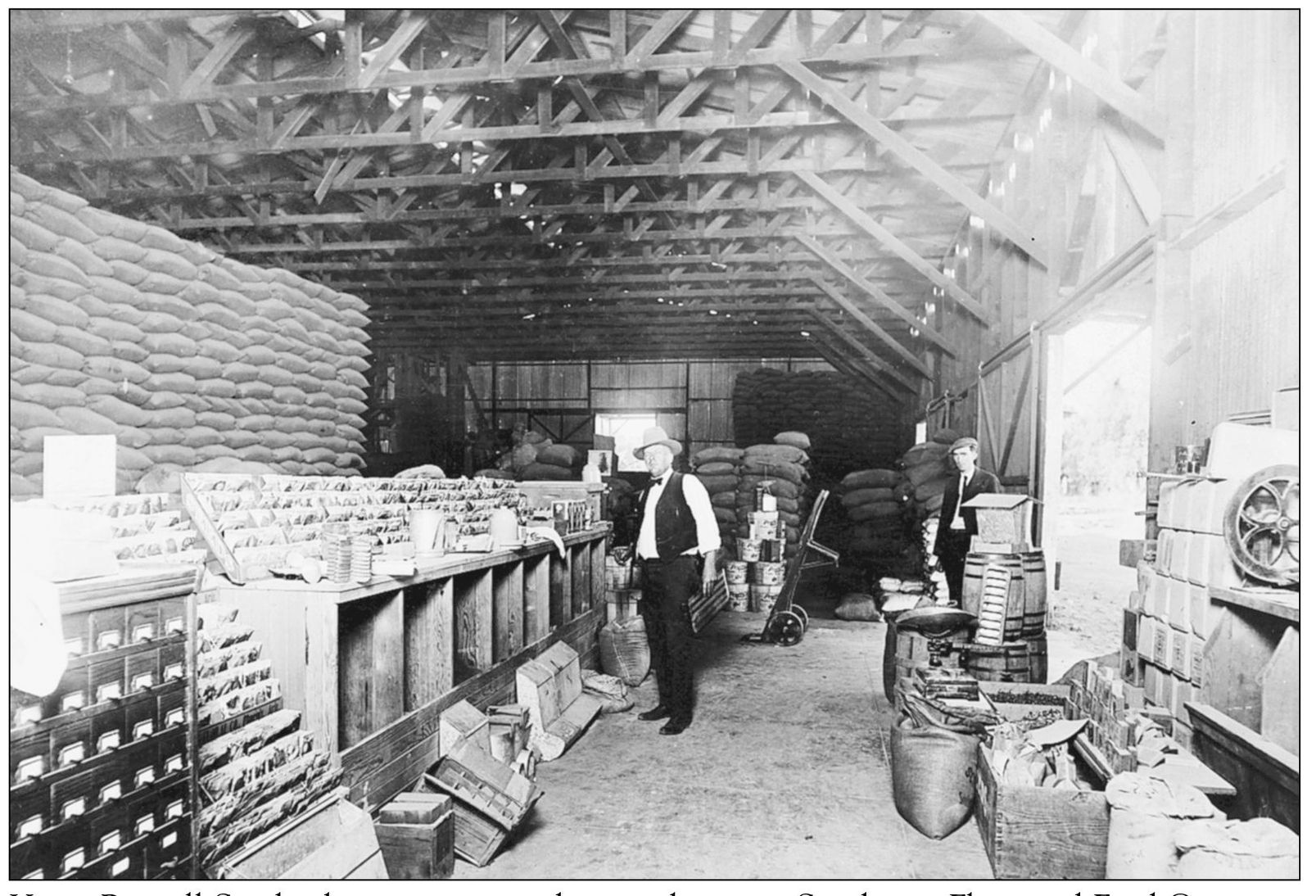

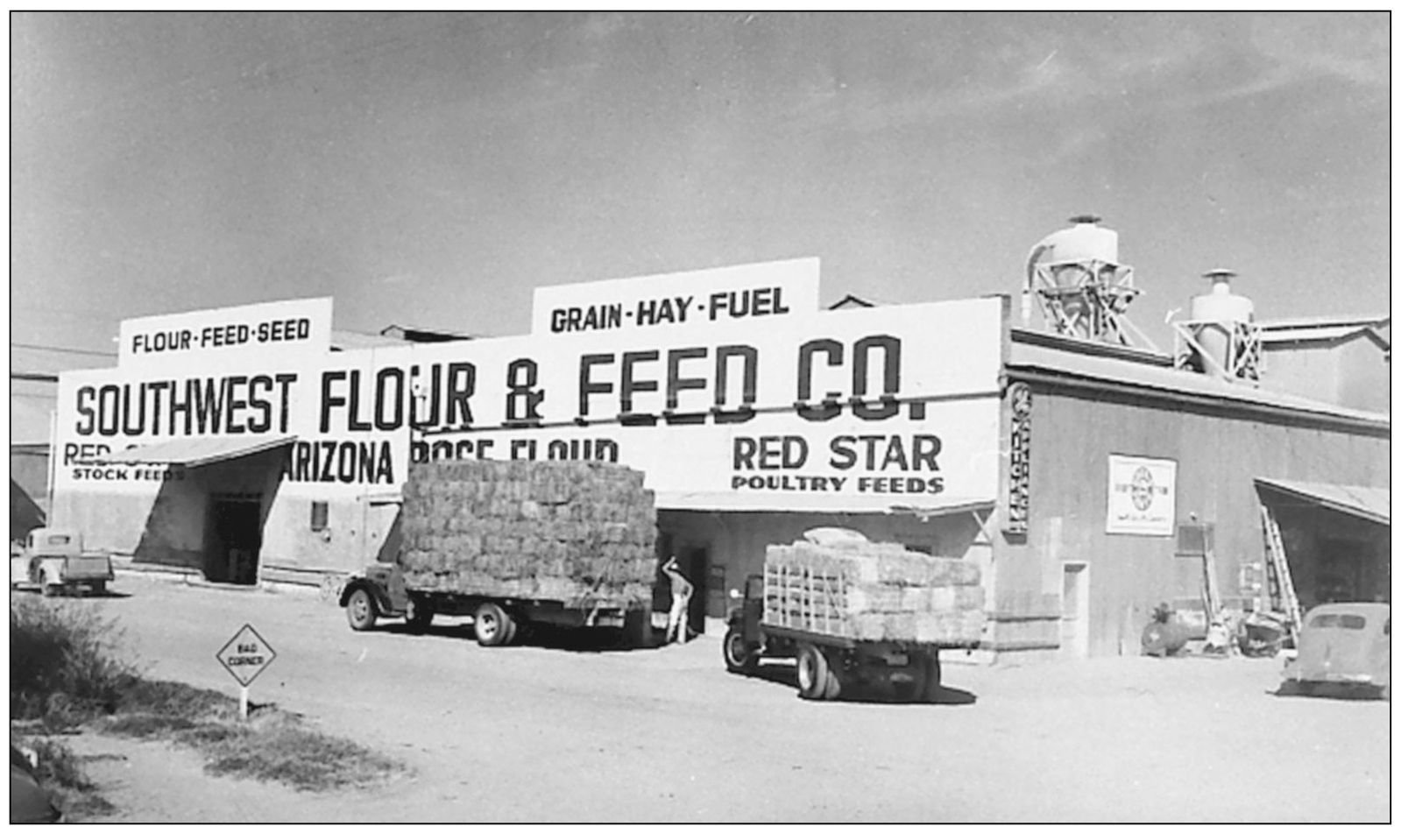

Harry Bonsall Sr. checks operations in his warehouse at Southwest Flour and Feed Company around 1920 (above). Southwest was one of Glendale’s leading businesses for decades, and Bonsall was a respected civic leader who was referred to by some as “Mr. Glendale.” Shortly after the plant opened in 1919, the Glendale News described it as “a modern and thoroughly complete plant for grinding and rolling feed.” And the farmer was assured that large tonnages of feed could be handled because the plant was “motor driven.” In addition to Red Star brand flour, Arizona Rose brand flour, and various feeds, Southwest stocked rock and block salt, coal, and wood. The warehouse (below) offered 10,000 square feet of space that could store up to 15 million pounds of grain.

Coming to Glendale in 1915, Charles M. Harper (above, left) established the Oasis News Company, which he soon expanded into Harper’s Drug Store. In 1918, he sold his drug store to Carroll M. Wood who changed its name to Wood’s Pharmacy (below). A few months later, in 1919, Harper bought Lower Furniture Store, located next to Grant McArthur’s secondhand store, from Delbert E. Lower and renamed it Harper’s Furniture Store. His stock included “moderate priced chairs, tables, rugs, dishes, stoves, beds, trunks, and many other items.” One of those “other items” was a lawn mower (above, left). Harper served as mayor of Glendale in 1934 and 1935. Harper’s partner, Holmes Sine (above, right), tries out a rocking chair.

Three young men (two barefoot) look over the wares offered by Stauffer’s general merchandise store in the early 1920s. Ray Stauffer grew up in Glendale and was one of the early businessmen in Glendale. He started with a small grocery and general merchandise store, but he always included a line of men’s furnishings and shoes as part of his stock. In 1917, he separated the men’s clothing department from the grocery and provisions department and added ladies and children’s shoes and stockings.

In 1920, after the Toggery moved into the building previously occupied by the Crystal Theater, something new appeared around the town square—a showcase storefront. Manager Bob Reynolds kept the window displays well outfitted with examples of the quality clothing lines he carried for women and children and for men and boys. Seen faintly in back of the building (right) is a storage tank for the municipal water system.

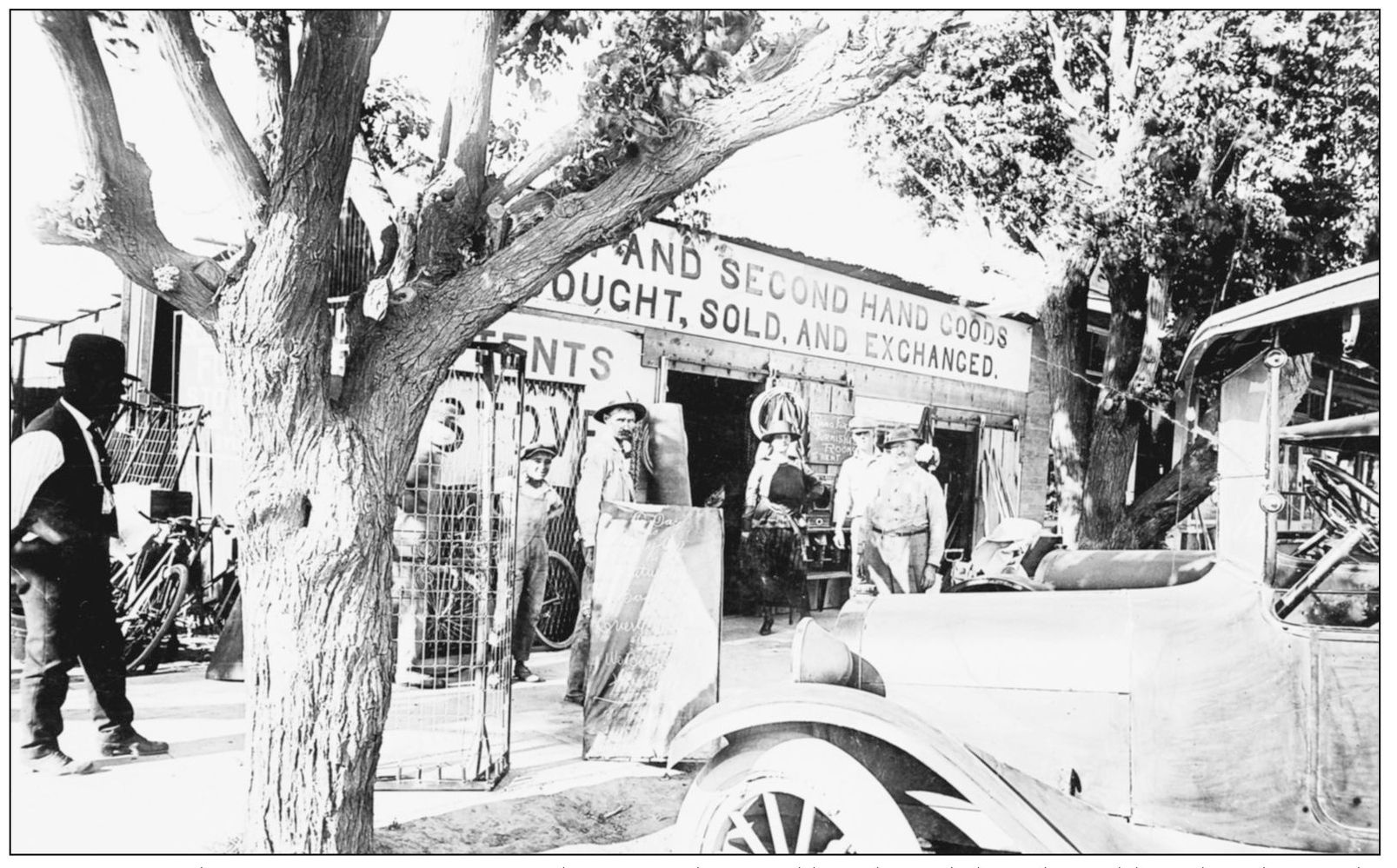

Grant McArthur’s corner in 1920 offered “new and second hand goods bought, sold, and exchanged.” McArthur died in 1920, after which his wife, Annie, ran the business for a short time before she sold out and moved away. McArthur’s was right downtown, located on the corner where Washington (Glendale) Avenue, Lateral 18 (Fifty-ninth Avenue), and Grand Avenue converge. Today part of the Municipal Office Complex parking structure sits atop the corner.

Irving “Irv” Thowson (center), standing behind the meat showcase of the Glendale Pay’n Takit (later Safeway), is ready to sell customers a slab of bacon from the six-deep pile on the showcase. When Thowson’s wife, Alma, helped at the market she brought her baby son, Gordon, with her. He was placed in a basket and put on a big shelf in the showcase, hopefully to sleep. Alma marked this 1921 image with an “X” (right of center) to indicate which was the baby’s case.

The McFadden/Morrell pool hall and cigar store was just one of several that came and went in the 1920s. Pool halls, or billiard parlors, were a favorite place of entertainment for some in the early days of Glendale. The proprietors of one pool hall, down the street from the town park, were James Ross “J. R.” McFadden and his brother-in-law, William “Bill” Morrell. In front was their cigar store and in a back room were the pool tables. The business partnership did not last long. J. R. was elected Maricopa County sheriff and in 1931 had the dubious honor of bringing the infamous “trunk murderess,” Winnie Ruth Judd, back to Phoenix from Los Angeles. When he lost his reelection bid in 1932, he blamed it on his participation in the Judd case. After McFadden and Morrell left the pool-hall business, the pool hall became a barbershop; in front was the barber and in back was a bathhouse. Thus a man could get a shave, a haircut, and his weekly bath all in one location.

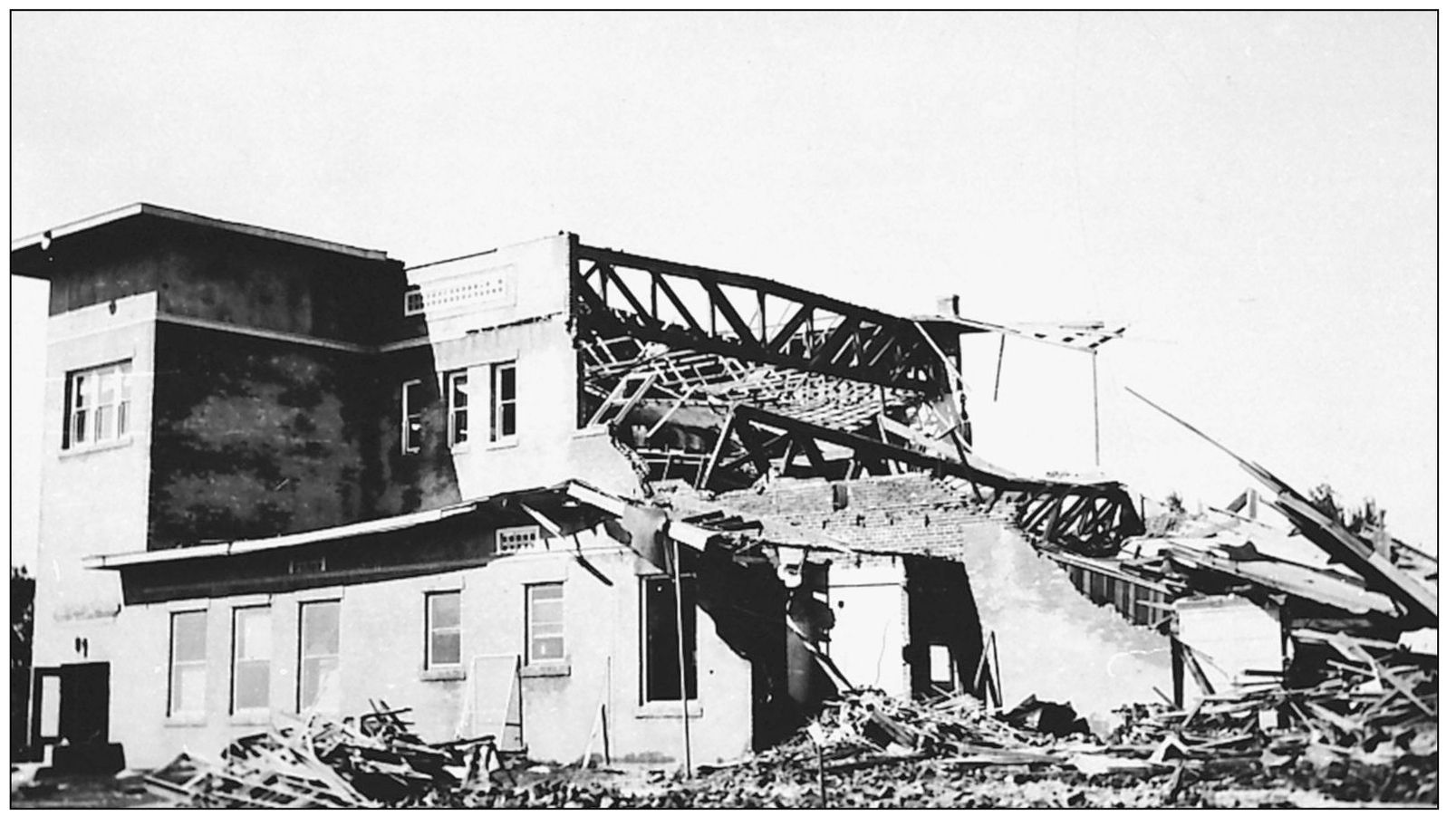

On August 19, 1921, Glendale was visited by the most destructive storm since its founding. The grammar-school auditorium (above and below) was particularly damaged. Its roof was almost completely blown off, and the north end of the building was demolished. The storm was described as a “miniature tornado.” It whipped Manistee Ranch, destroying a silo and drenching the home’s interior. It took out several houses in Catlin Court and narrowly missed the Methodist Church. The tornado ripped roofs off of Anderson’s Garage, Juncker’s Blacksmith Shop, Halstead Lumber Company, the warehouse of Glendale Ice Company, and other buildings. The water-pumping plant was put out of service, as was the electric company. Telephone service was also disrupted for hours, and in the downtown area many signs and awnings were cast loose.

Walter’s Café was located south of the Gillett Building in the early 1920s. Cafes came and went often, either because business was poor or the owner got tired of the daily routine. Over the years, there were several different cafes in this same location. Notice that on the counter by the cash register is a small “house.” It is an up-to-date weather predictor. If the white figure emerged from the house, it would be good weather, and if the black figure (often a witch) emerged, rain and bad weather could be expected. Devices such as this were popular well into the 1940s. They worked pretty well in Glendale, where seldom there was bad weather.

Texaco products were available in 1923 at the service station of Homer C. Ludden and Charlie E. Gillett. Gillett’s daughter Flora (Gillett) Statler was one of the attendants who pumped gas. Later she opened a real estate office in town with Ludden. Besides developing the Floralcroft Addition to Glendale, Statler and Ludden secured the agreements to purchase the Luke Field properties in 1940 to start development of the town of Surprise, Arizona.

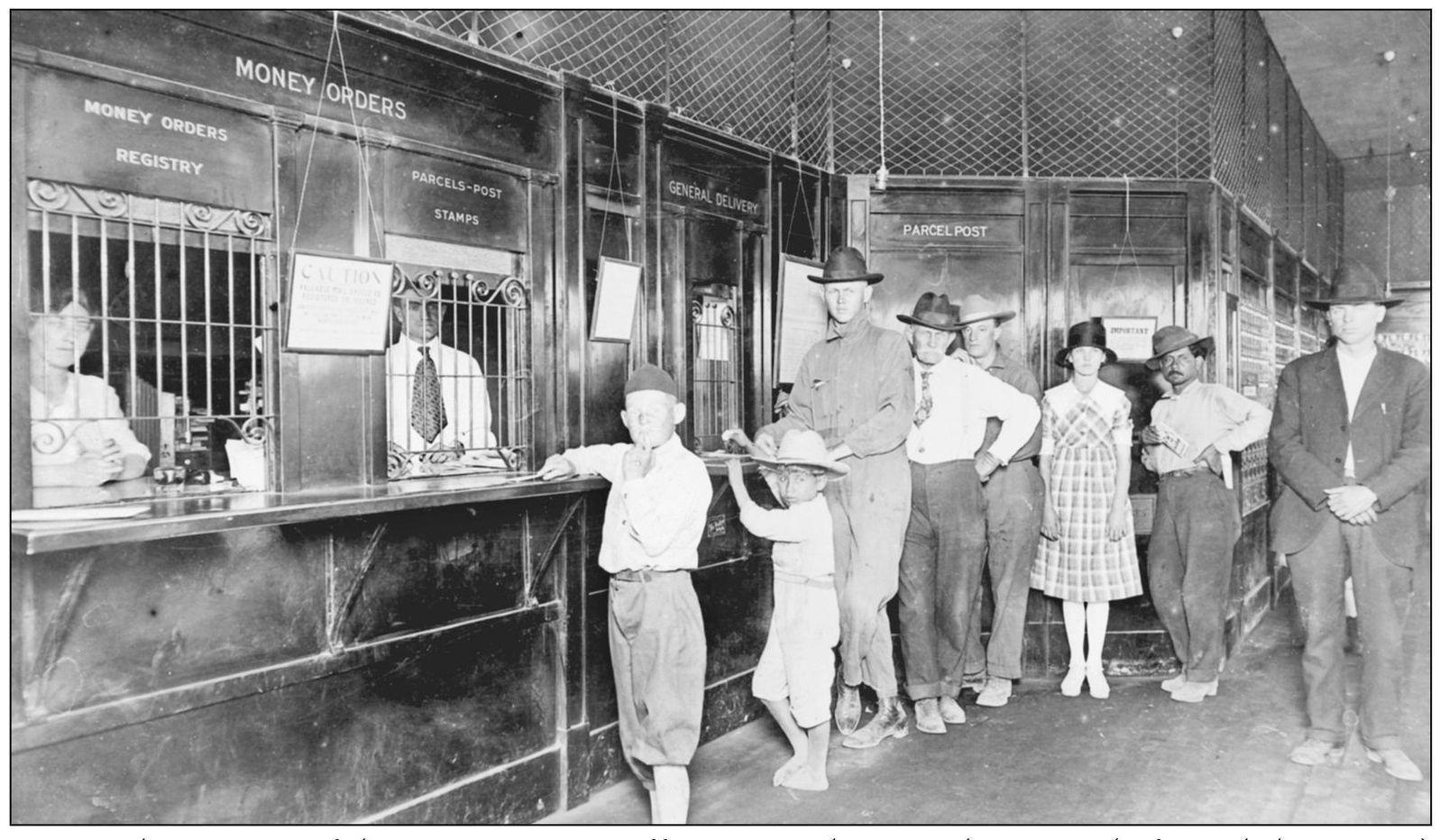

Here is the interior of the new U.S. post office on south Second Avenue (Fifty-eighth Avenue) in the early 1920s. Even the littlest customer wore a hat in those days. The barefoot boy at the front of the line is Frank Thuma. Moving post-office locations seems to correspond to national elections. A change in the political party controlling the government resulted in appointment of a new postmaster, and often the post office would be relocated. During Franklin Roosevelt’s years in office, there was only one postmaster in Glendale and one location for the post office.

Downtown Glendale in the 1920s had streets lined with the automobiles of shoppers. This image is looking south down First Avenue (Fifty-eighth Drive) toward the Crystal Ice Company warehouse. On the left is the town park (Murphy Park). South of the park is Newman’s Department Store and Sine Brothers Hardware. On the right are O. S. Stapley’s, a vacant lot, the police department and jail, and city hall.

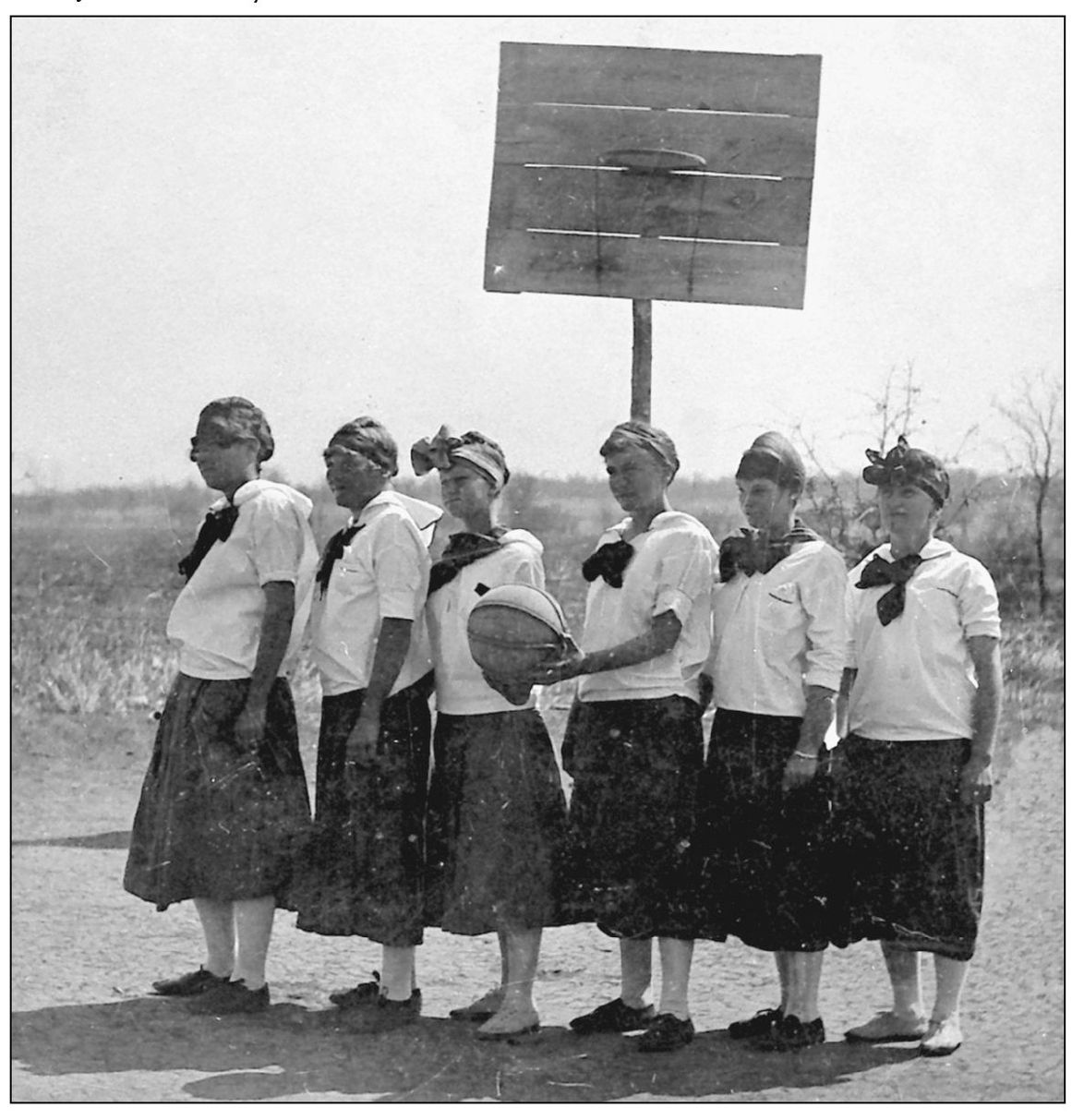

The boys were not the only athletes at Glendale Union High School in the early days. Although they did not participate in rough-and-tumble sports such as football, the high school girls did have a basketball team that competed with other teams. Perhaps practicing outdoors on a graveled court with a dilapidated basketball hoop and backboard made the girls tough. In the 1920–1921 season, the girls’ team won every game they played and claimed the state championship.

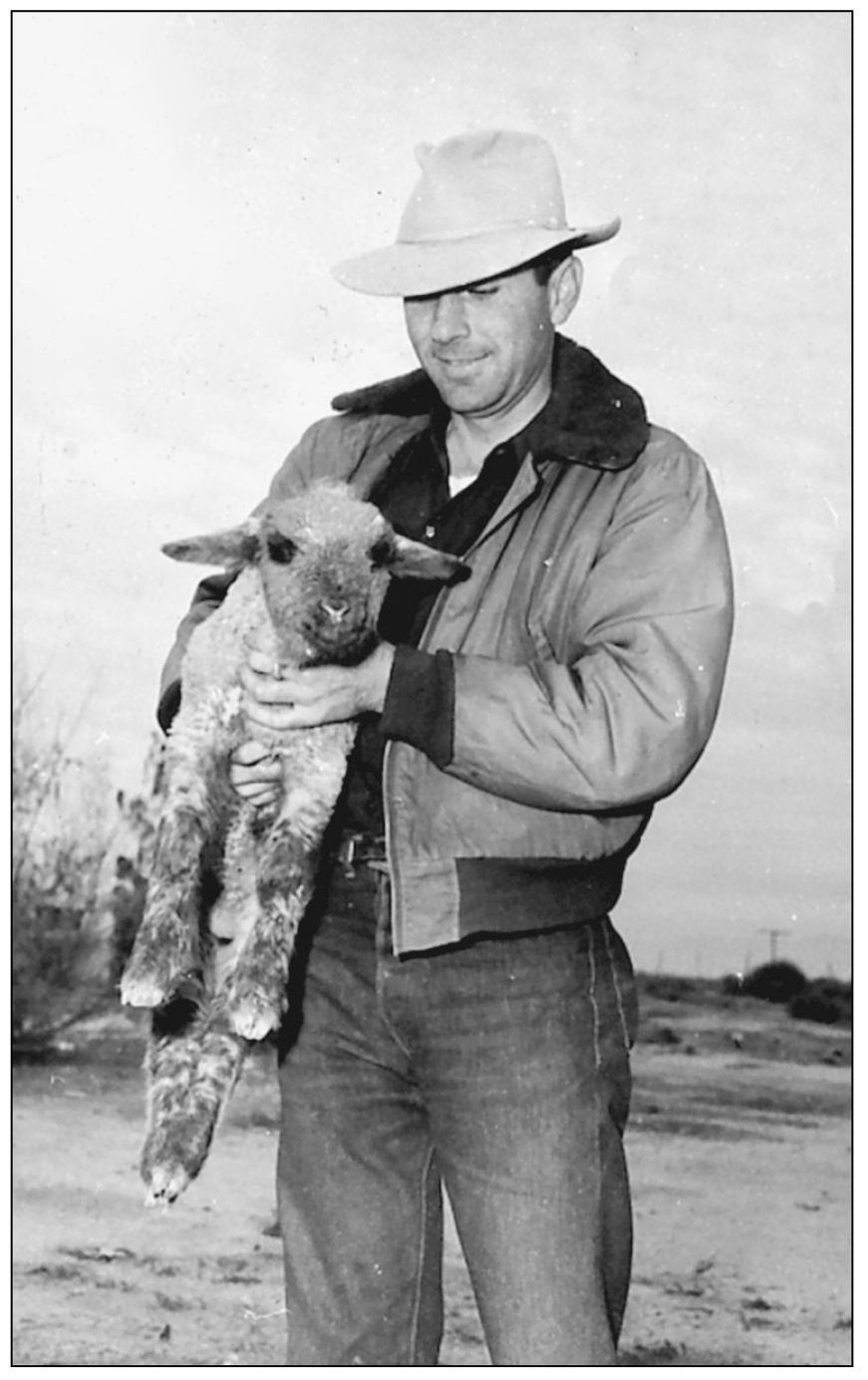

Joseph Ysidor Otondo (left), a Basque sheep rancher, had winter pasture for his flock in Glendale and summer pasture in the high country in northern Arizona. The Otondo family visits dad (below) and the herd on the move near Glendale. Several Basque families, among them the Ajas, Ipharrs, and Hidalgos, made Glendale their home. During the school year the families stayed in Glendale, but during summer vacations they lived in the sheep camps up north. Other ethnic groups that formed important segments of the Glendale community were the Japanese, Chinese, Hispanics, Russians, East Indians, and those of Middle Eastern descent.

On their parents’ farm west of Glendale, three Treguboff boys tweak the tail feathers of a turkey that soon took its revenge on the boys. But farm animals were not pets or toys, so the turkey eventually ended up in an oven.

Not every farmer had crops large enough to be shipped to distant markets in railroad car lots. The Darby family, for example, trucked produce from their small farm the few miles to Phoenix to sell at the farmer’s market. This day, in 1927, the truck is loaded with crates of lettuce.

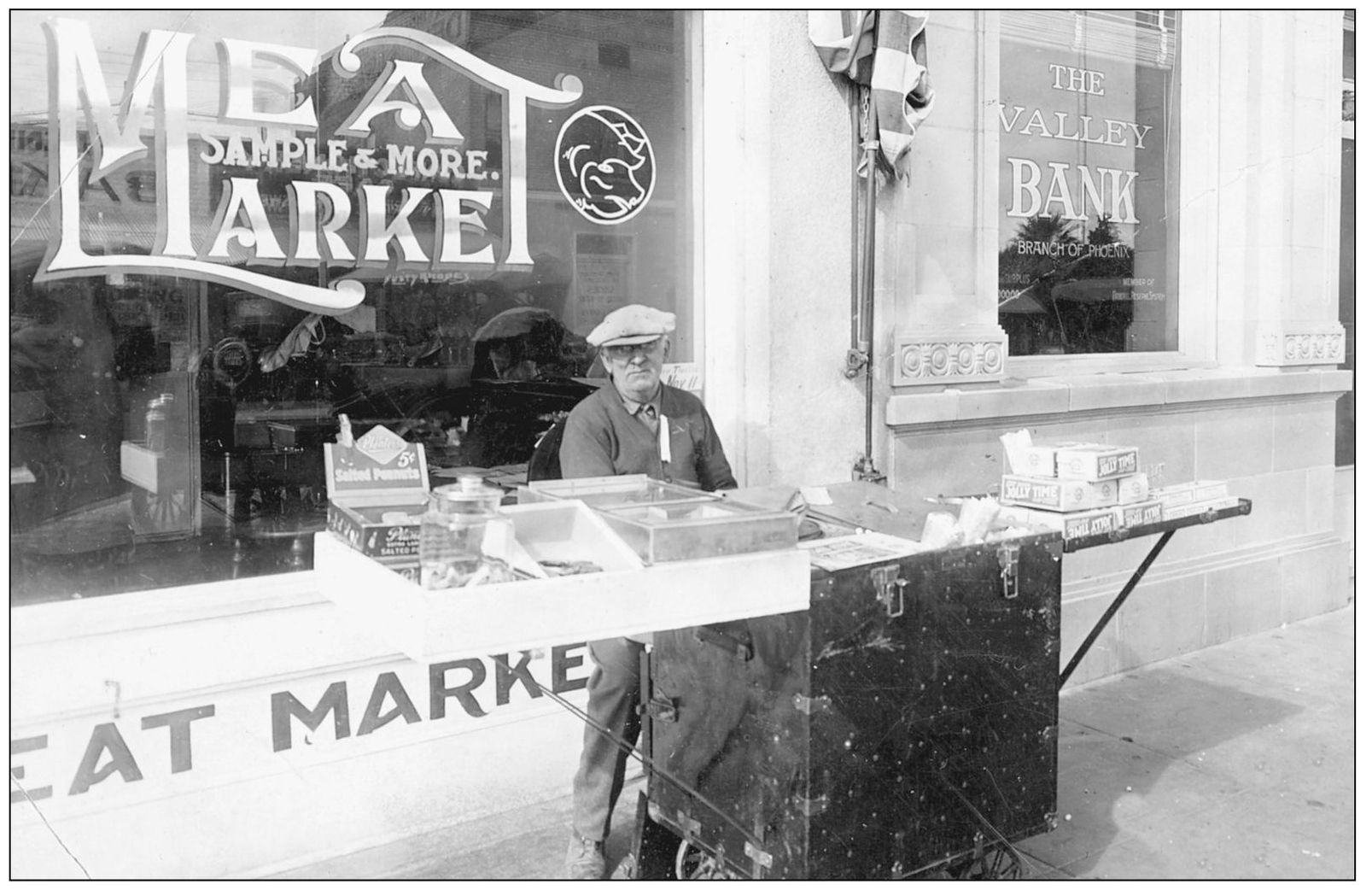

Sidewalk merchant Solomon O. Furrey for a few years was a fixture on First Avenue (Fifty-eighth Drive), just south of Glendale Avenue, in front of Sample and More’s meat market and next to the Valley (National) Bank. Listed in the city directory as operating a confectionary stand, Furrey, pictured here in 1924, offered candies, peanuts, newspapers, and other sundries to passers-by.

Members of the German Baptist Brethren (Church of the Brethren) visit with other members of the congregation following the morning worship services in this 1920s image. They were plain dressers by tradition. Elder Ola Gillett (hatless by the window) is dressed in a traditional collarless plain suit and not wearing a tie. Facing Ola, with her back to the viewer, is his wife, Minnie, wearing the traditional woman’s prayer-cap covering.

Children enrolled in the Daily Vacation Bible School of the Calvary Baptist Church stand washed and scrubbed for their photograph in front of their church in June 1927. Churches have always been an important part of Glendale’s social and cultural life. In the 1930s, there were more than a dozen denominations in town.

Jeff A. “Dad” Turner (left) and his wife came to town in 1919 from Missouri and opened a confectionery stand on the west side of the town park. In 1920, he took over the City Café down the street. In 1926, Turner was appointed postmaster at Wittman, 25 miles northwest of Glendale. He moved there and opened a café and service station. From earliest times in Glendale, there was always a café or restaurant on the square, even to the present day.

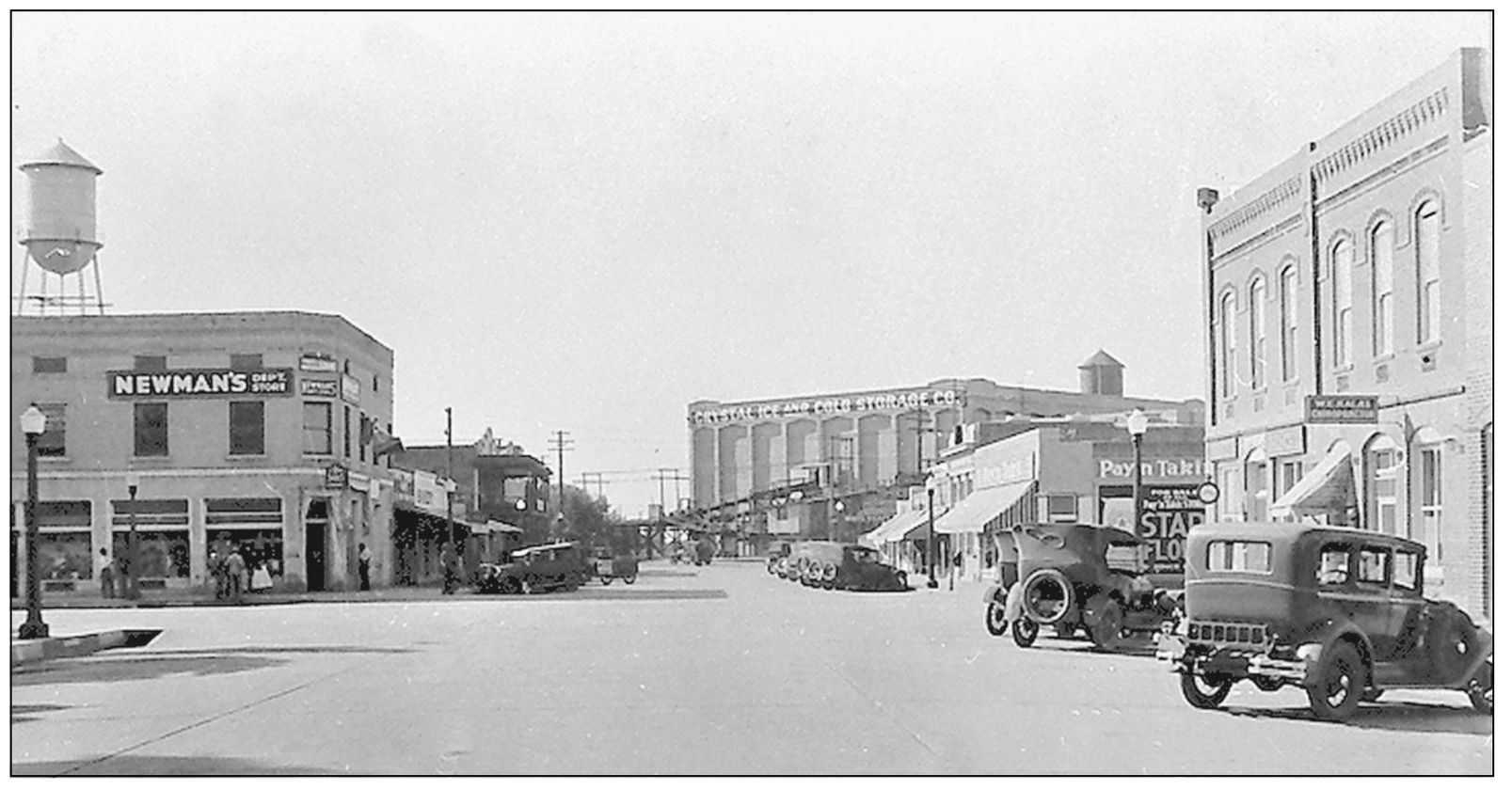

This is downtown Glendale, looking south along First Avenue (Fifty-eighth Drive), as it looked in the late 1920s. On the left is a storage tank of the municipal water system. Newman’s Department Store occupies the Gillett Building. The large building at the end of the street, which parallels Grand Avenue and the Santa Fe railroad tracks, is the Crystal Ice and Cold Storage Company plant.

The Valley National Bank in the mid- to late-1920s was a busy place, but hard times were ahead. The nationwide banking crisis of the early 1930s ruined many banks in Arizona and the nation. Valley National, however, survived and became a powerful Arizona bank. It continued until 1993, when Bank One acquired it.

An Arizona sleeping porch was little more than a screened room with canvas flaps of one sort or another to regulate the airflow through the openings. In the 1920s, the sleeping porch of Esther and Henry T. Burton had moveable flaps on two sides of the room. By propping open the flaps in hot weather, one would have a cooler place to sleep than in a bedroom. Besides, many small homes had only one bedroom and a sleeping porch. In that case, the whole family would sleep on the porch, and the bedroom would be saved for guests or when someone was sick. Evaporative coolers and air conditioning eliminated the need for sleeping porches.

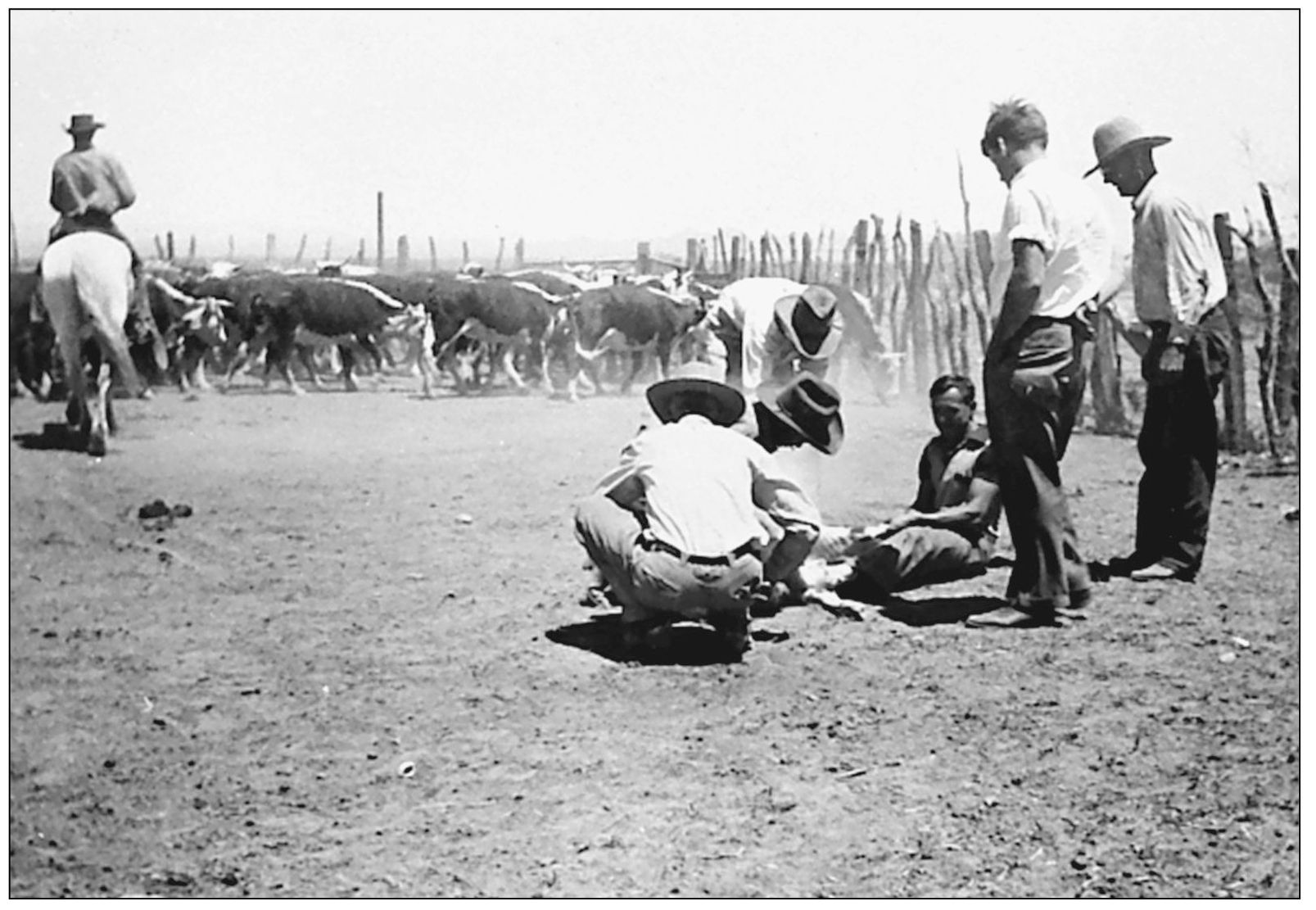

Branding young steers with the Sands “LS” mark in the 1930s at Manistee Ranch was a hot and dusty job for wranglers. Besides being used to raise crops, the ranch served as a feedlot to fatten cattle for market. Manistee Ranch was on the outskirts of Glendale until it was surrounded by a growing city. Half the ranch was sold off bit by bit in the years after World War II, but the rest was still used for ranching activities until 1996.

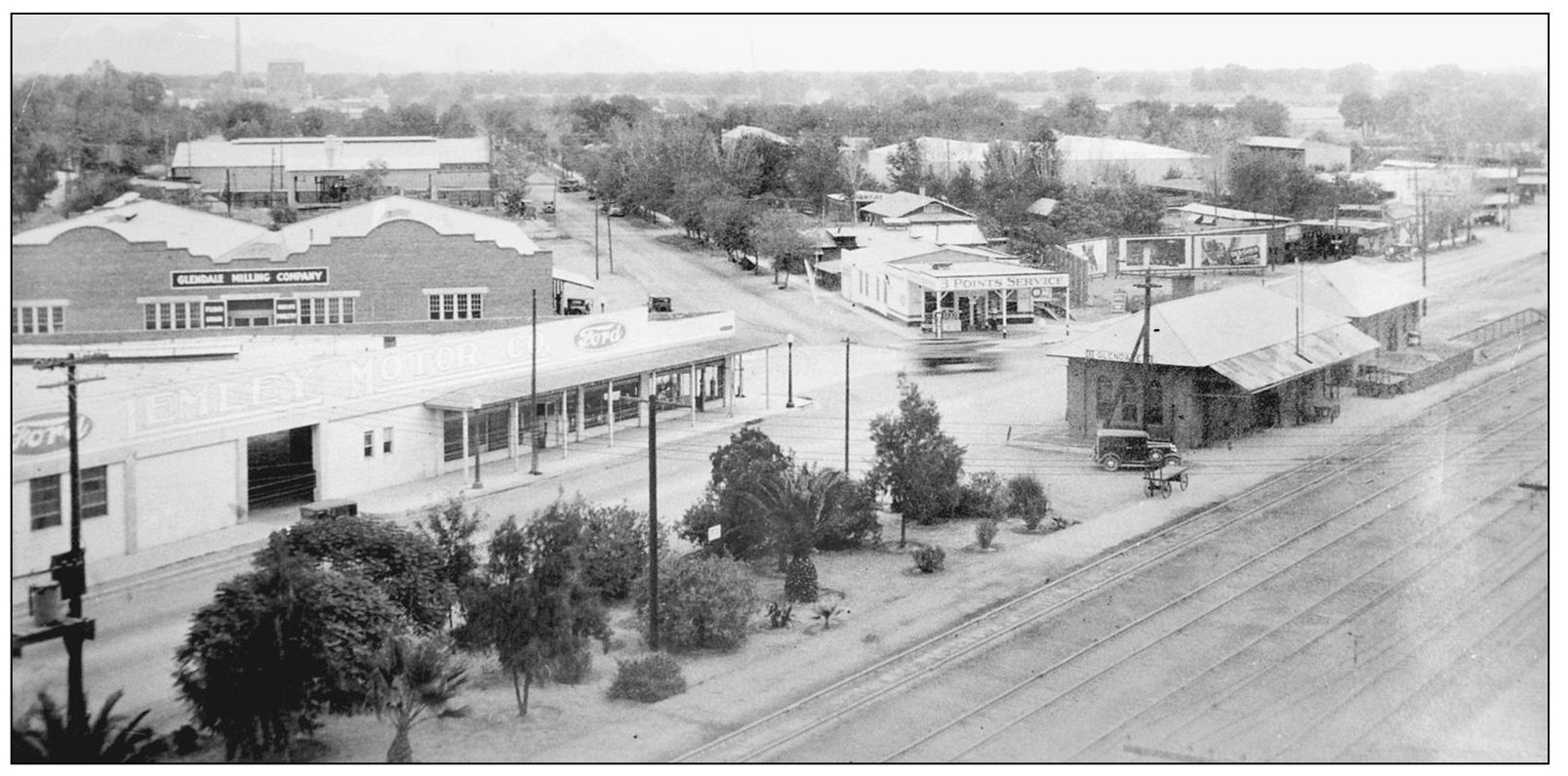

In 1930, the heart of Glendale centered on the all-important railroad tracks and Santa Fe depot visible in the right foreground of this image. On the left, across the street (Grand Avenue) from the trees, is Lemley’s Ford dealership. Behind the Ford building is Glendale Milling Company, and behind that is Southwest Flour and Feed Company. On the left skyline is the faint image of the Sugar Beet Factory and its landmark smokestack.

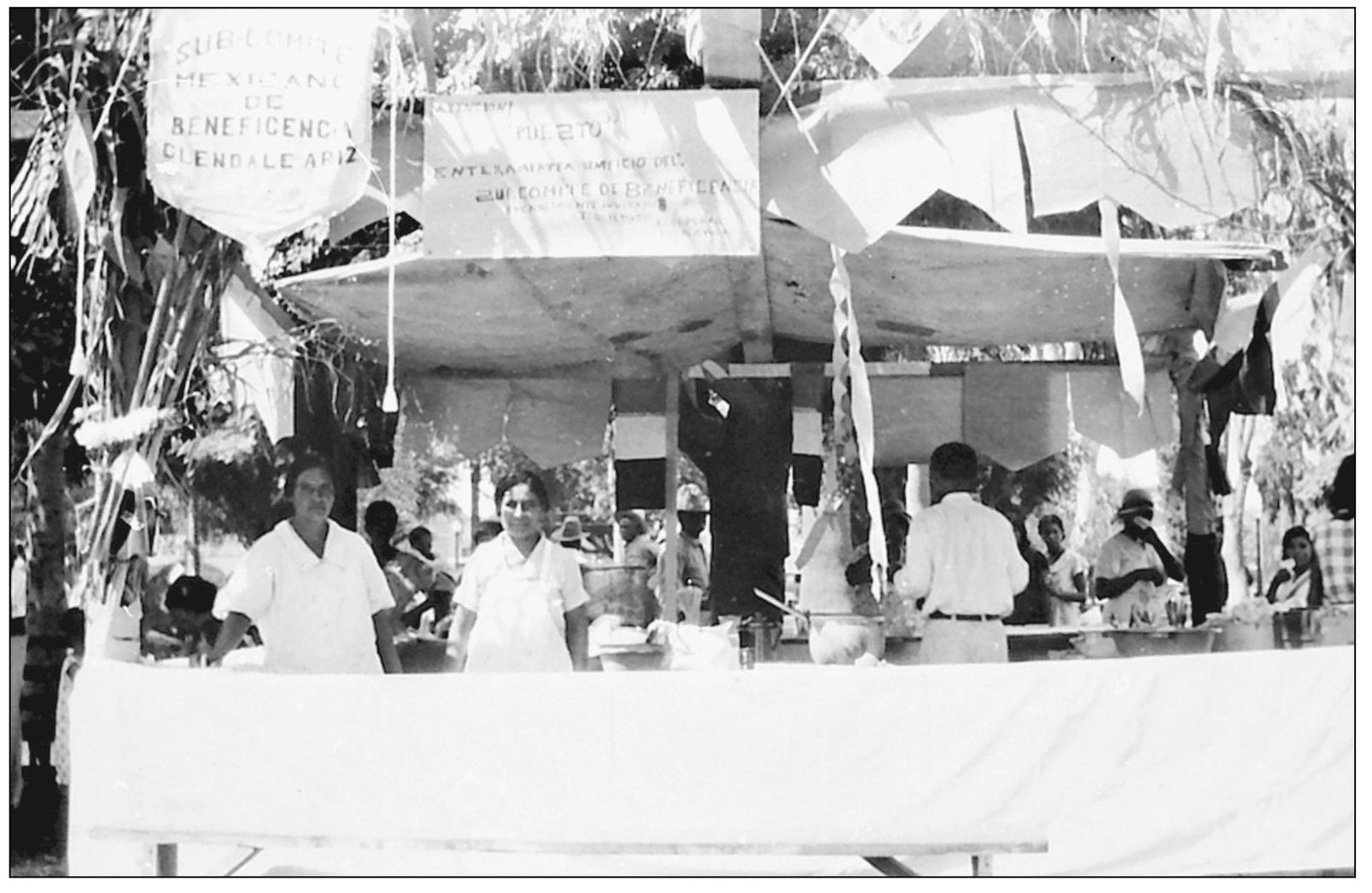

Fiestas Patrias, a celebration of Mexican independence from Spain, dates back to the early 1930s in Glendale and continues today each September. The celebration in and around the town park was a source of enjoyment for all of Glendale, not just the Hispanic community. A typical Fiestas Patrias would last two days and evenings, and it would include the crowning of a queen to reign over the colorful festivities, a parade (above), music, speeches, games, contests, and street dancing. Especially important were the food booths (below) set up in City Park, where, as the Glendale News put it, “real Mexican food was served.” Although suspended for a time during World War II, the fiesta was reinstated in 1947 to the delight of people all over the Salt River Valley. These images are from the 1932 Fiestas Patrias.

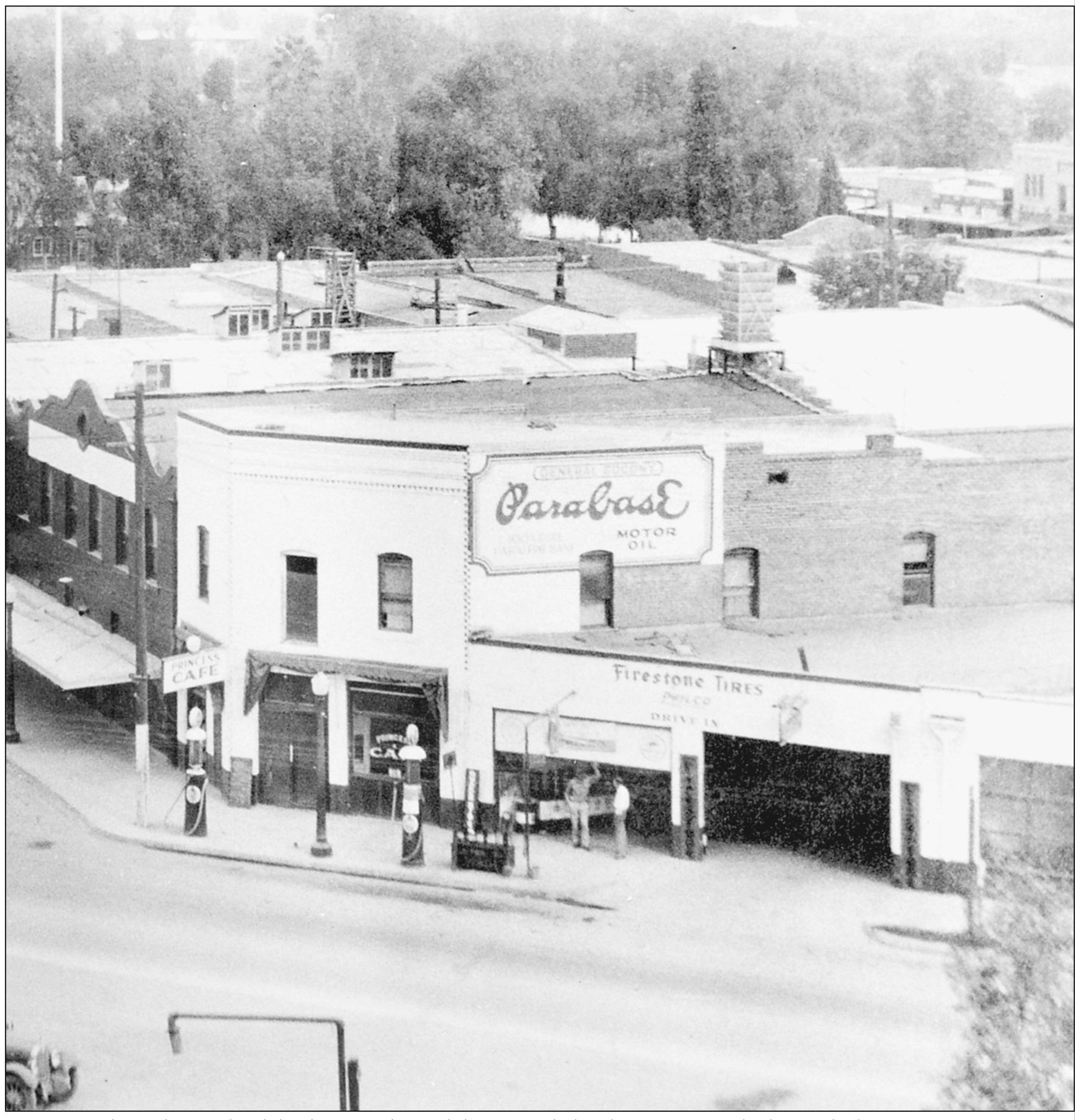

This is downtown Glendale as it looked around 1930. Grand Avenue is in the foreground, and the trees of City Park are seen beyond the buildings. In the middle of the park is a very tall flagpole.

Throughout Glendale’s history, the park has provided a place to rest and relax and a location for community activities and celebrations.

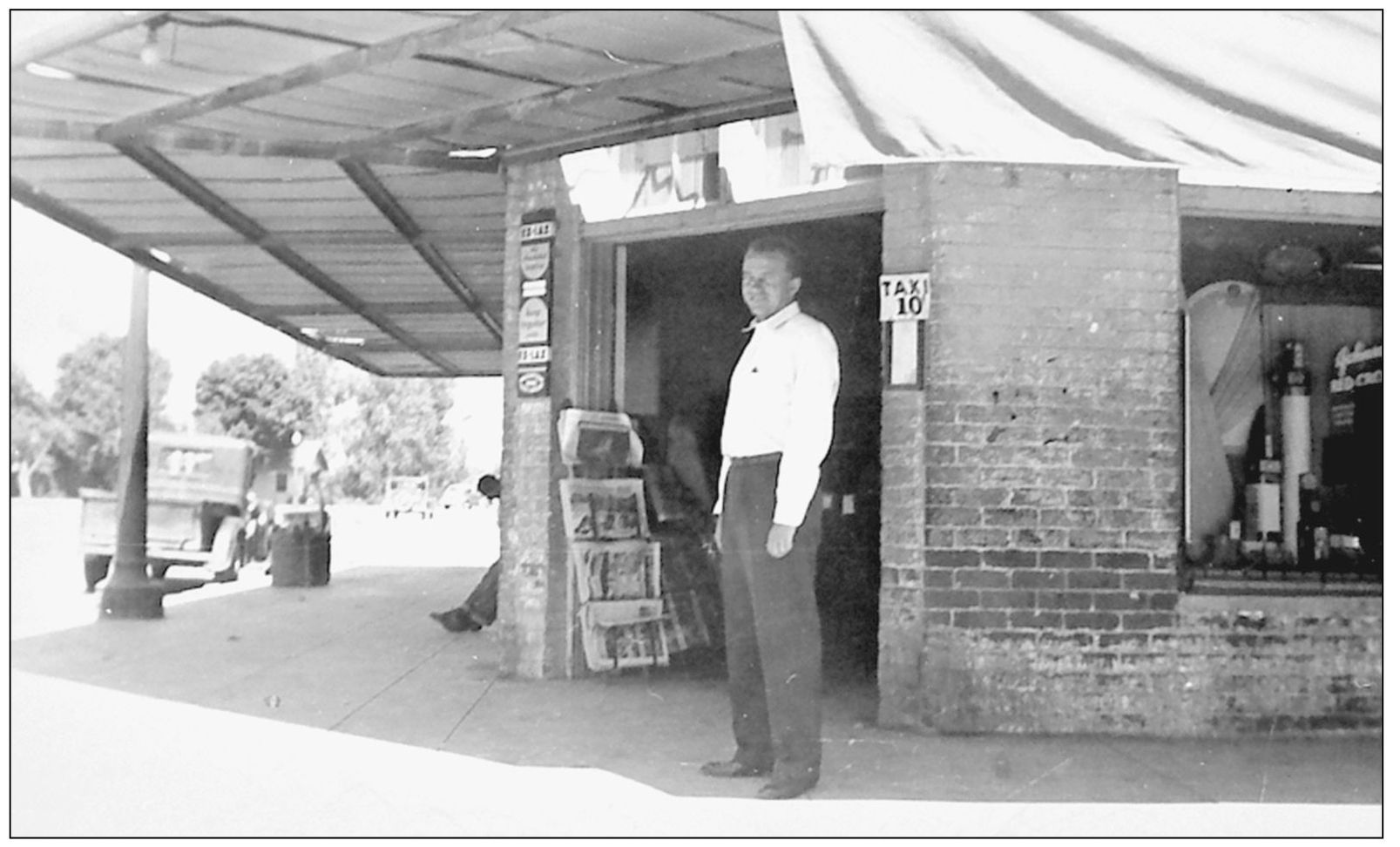

Attorney Richard S. Gilmore checks out the taxi stand in front of the Ever Ready Drug Store in the Hine Building in the mid-1930s. Built in 1913 by investor Alice Hine, the structure was added to in 1919 to accommodate Beaty’s Grocery. In 1928, Bill Betty opened the Ever Ready Drug Store in the corner store. By the 1940s, Ever Ready had been sold to Shel Neukom, who operated it for 25 years.

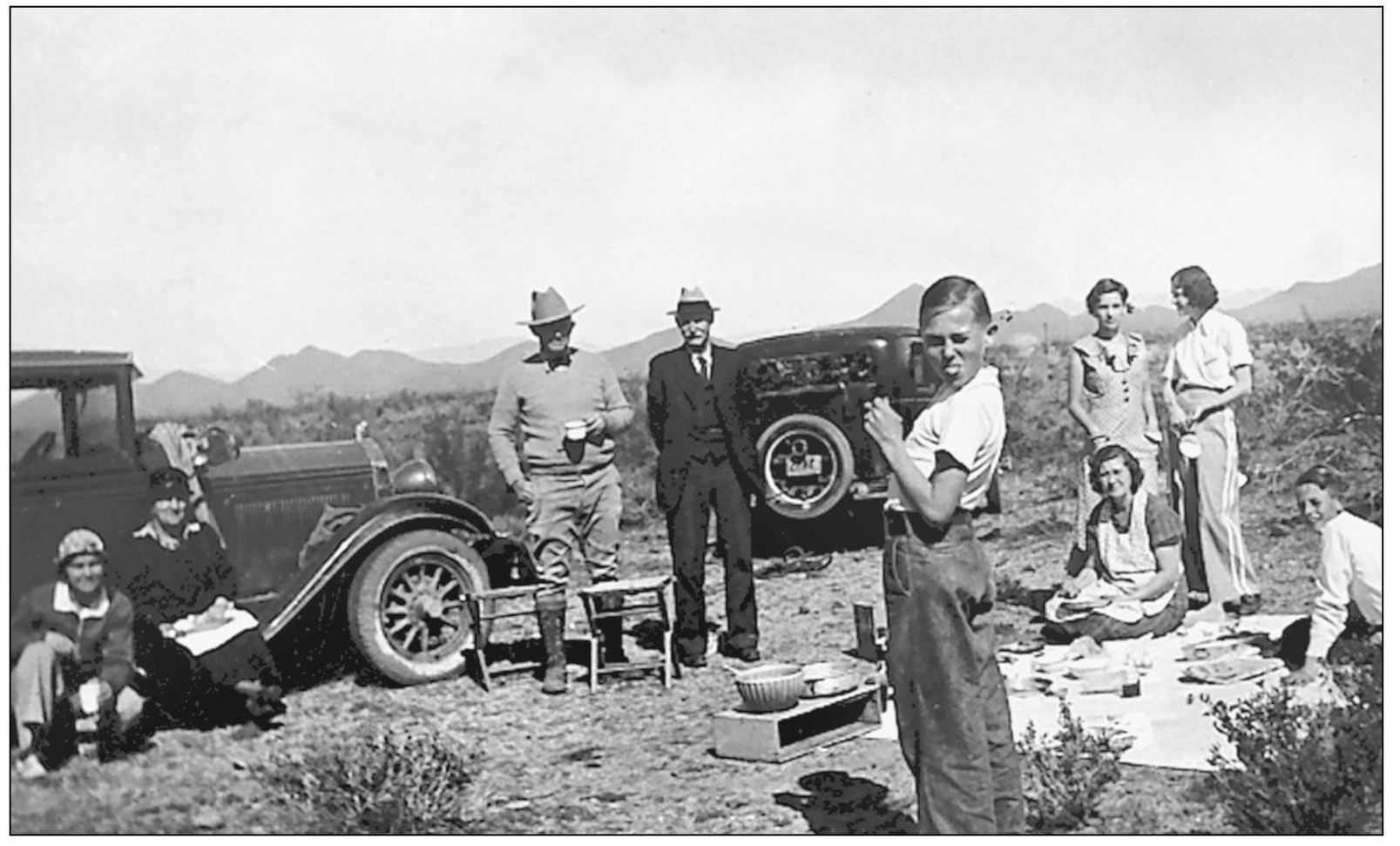

Picnicking on the desert was just as popular in the 1930s as it was in the 1920s. Around 1935, the Whitney and VanCamp families share a picnic excursion a few miles from Glendale. From left to right are Gladys Whitney, Maude Whitney (wife of Clarence), DeForest VanCamp, Clarence T. Whitney, Don VanCamp (sticking his tongue out), and Jean VanCamp (the wife of DeForest, sitting on the blanket).

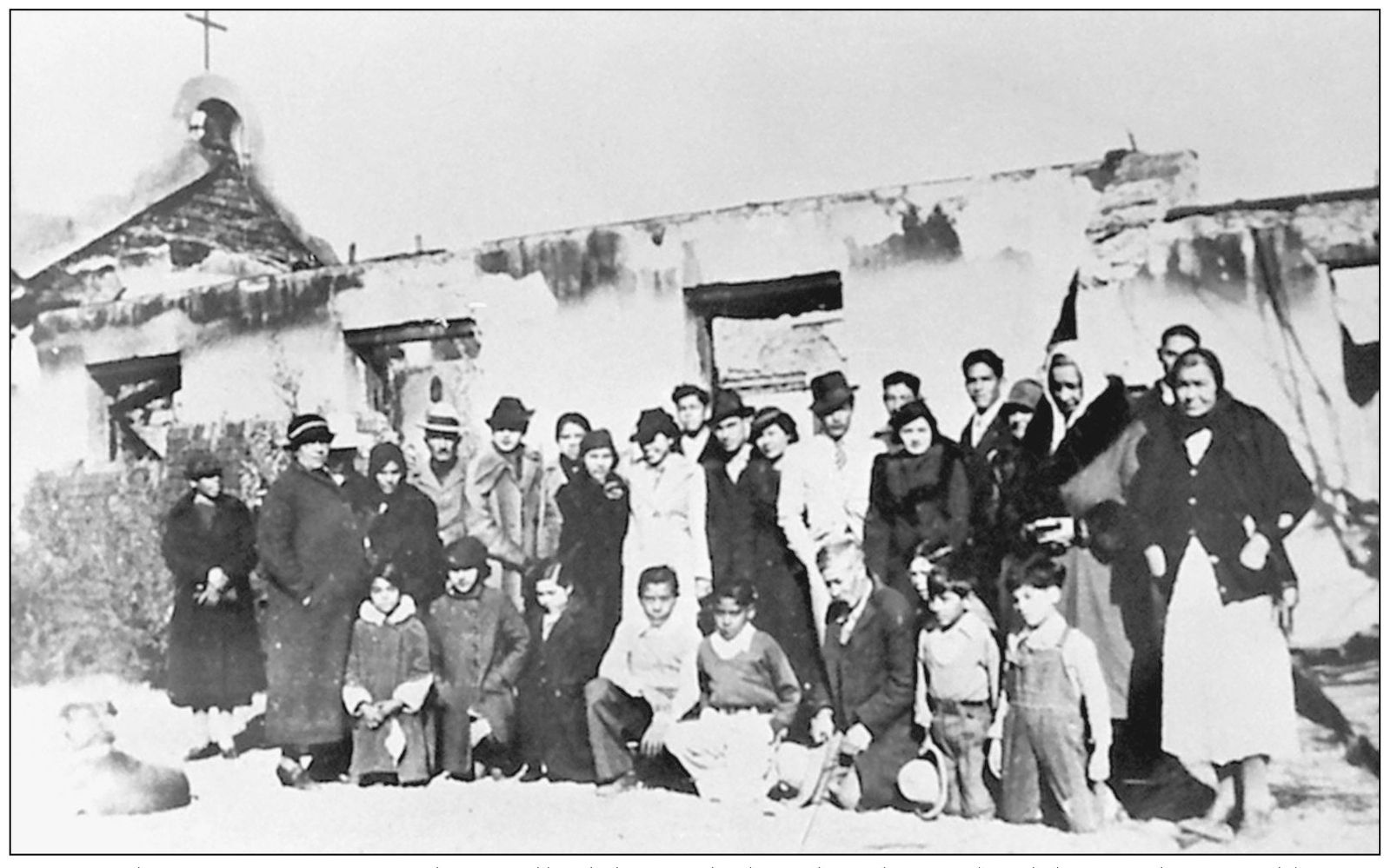

On Sunday, January 3, 1937, the small adobe Catholic Church in Glendale was destroyed by fire (above). The congregation, mostly Hispanic, was determined to rebuild their house of worship, but it would not be built of adobe, but stone. Black rocks were hauled by the congregants from the Salt River and the Black Canyon to build the new church. By the summer of 1937, the “Rock Church,” as it was known locally, was ready for services, although the interior was not finished. The new church (below) was given the name of Our Lady of Perpetual Help. In 1953, the church acquired 11 acres of Manistee Ranch on which they built a school. Over the next 20 years, other buildings were added and finally a new sanctuary was built to replace the old Rock Church, which was abandoned and torn down.

High school students often congregated after school in the late 1930s at a drug store soda fountain or café. Ezra Fike opened Fike’s Café on Glendale Avenue in 1937. He had operated a number of cafés in Glendale and Phoenix over the previous two decades. The students laughing from left to right, are Madge Slack, Jeanne Ipharr, Pat Adams, unidentified, Ruth Sparks, and Dean Smith.

Downtown Glendale, looking east down Glendale Avenue in the late 1930s, appeared to have few parking spaces left for shoppers. On the right is the Gillett Building, which is housing Wood’s Pharmacy. The trees on the left mark the south edge of City Park.

In “the good old days,” entertainments were quite different: no television, no malls to cruise, and no rock concerts. There were movies (silent until the late 1920s), and beginning in the early 1920s there was radio. From time to time, there was a Chautauqua or a circus in town. In small towns such as Glendale in the 1930s, most entertainments were homegrown. A band gave concerts in the park, the Glendale Grays matched their skills with another baseball team, and everyone went downtown on Saturday night. In October 1938, the Glendale Herald reported, “The most fashionable and elegant wedding of the year will take place . . . at the Glendale Grammar School [today’s Landmark School]. This Tom Thumb affair will be given by fifty tiny tots of the community.” This play, a mock wedding, had a practical purpose as well as entertainment, as it raised money for the school’s milk fund. Some of the Tom Thumb Wedding cast, from left to right, are Carol Coffelt (maid of honor), Nancy Stockham (matron of honor), and John Case (ring-bearer).

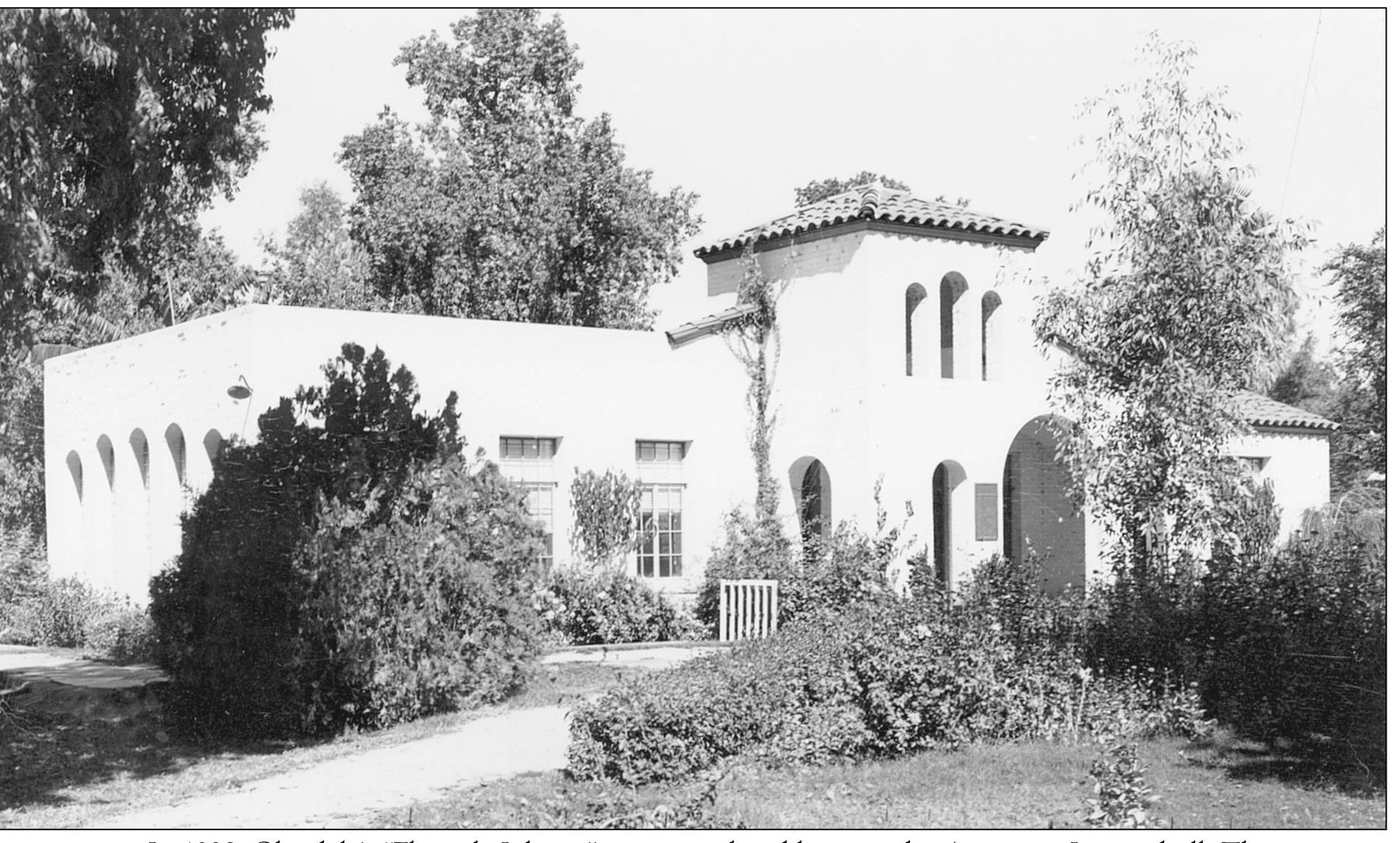

In 1938, Glendale’s “Flagpole Library” was moved and became the American Legion hall. The library was a wooden building erected in the town park (Murphy Park) in 1917, encircling the town’s single-piece, 110-foot wooden flagpole. A new, much larger brick library (above) was built in the park with Works Project Administration funds. The flagpole was not incorporated into the new structure but was moved and remained a prominent feature of the park until 1964 when it was replaced for safety reasons by a steel pole. The wooden flagpole had been fashioned from an Oregon tree and shipped to Glendale on three flatbed railroad cars in 1911. Originally intended for the Phoenix Y.M.C.A. grounds, the pole languished across from the Hotel Glenwood until 1912 because of the difficulty of moving it. Then Glendale acquired the pole, hauled it to the park with the help of the Sine Brothers, and erected it. The 1938 library was torn down in 1970 and replaced in 1971 by the current library building, the Velma Teague Library.