The Chief Engineer

‘Civil-engineers are a self-created set of men, whose profession owes its origin, not to power or influence, but to the best of all protection, the encouragement of a great and powerful nation.’

Preface to Reports of the late John Smeaton, FRS, 1812

During Brindley’s own lifetime, there were other engineers at work on other canals, but their activities tended to be overshadowed by the work of Brindley himself. His was the ‘brand name’ that all canal proprietors wanted on their product. After his death, a new generation of engineers came forward, the men who built the canals that spread across the country throughout the mania years of the 1790s and on into the early 1800s. Work on canals made some of them famous; William Jessop, who was responsible for completing one of the main arms of the ‘cross’, the main canal system that linked the four great rivers of England, Trent, Mersey, Severn and Thames, with the construction of the Grand Junction Canal; Benjamin Outram, who travelled throughout England and Wales building ‘tramways’ (the names ‘tram’ and ‘Outram’ have no connection beyond happy coincidence); John Rennie, father of an equally famous son, chief engineer for canals as far apart as the Lancaster and the Kennet & Avon. Other engineers worked on canal projects, but made their names in other fields. John Smeaton, for example, first made his reputation when he built the Eddystone lighthouse. These were the men who became famous and rich. It would be impossible in the space available to give detailed biographical essays on all of them – it would also give an unbalanced view of canal building. True enough they were the ones whose names became linked with the more spectacular canal projects – we talk of Jessop’s Grand Junction or Outram’s Peak Forest – but to dwell exclusively on the chief engineers of these works would be grossly to undervalue the contribution of others, not least the men on the site who did most of the actual work. It would also be unjust to deal in detail with those few famous men at the expense of other equally competent, if less famous, engineers. So the object of this chapter is to give some idea of who the chief engineers were, but to concentrate more on the work they did and the kind of lives they led.

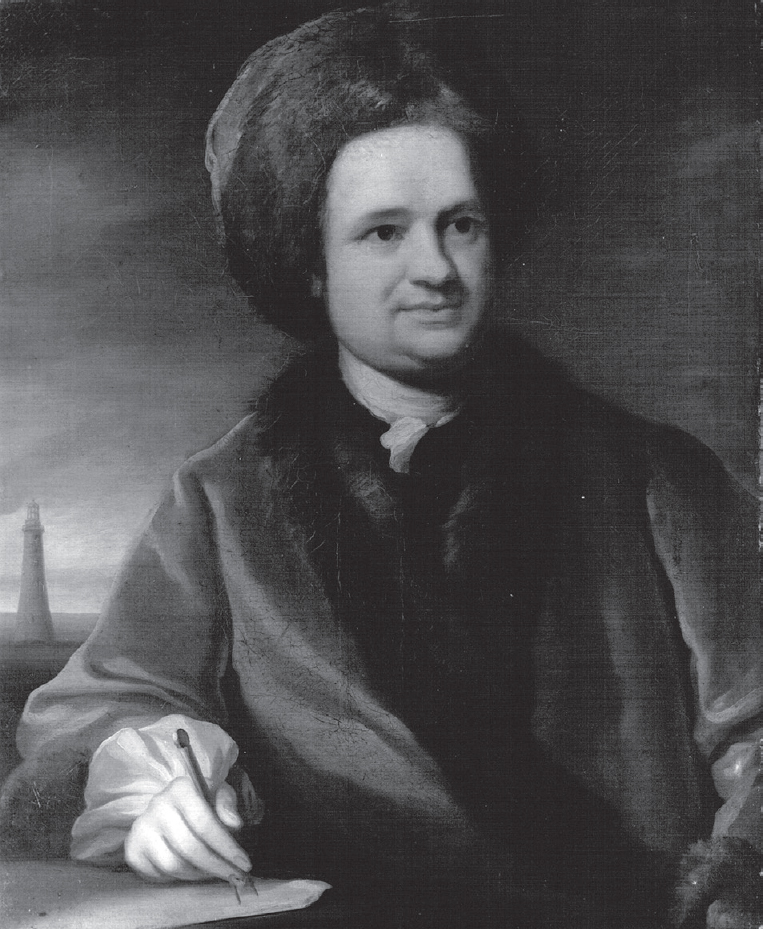

Throughout most of the canal-building periods there was still no recognised form of training for a canal engineer, or indeed for any other kind of engineer; so the chief engineer would have arrived at his exalted position by any one of a number of different routes. John Rennie, for example, followed a career that was very similar in some ways to that of Brindley, beginning as a craftsman and ending as a professional engineer. He had the advantage, however, of having had rather more education than the almost illiterate Brindley. John Smeaton, on the other hand, came from a quite different background and followed a quite different career. He was born in Austhorpe, near Leeds, in 1724, and even as a child seems to have been fascinated by mechanical objects. His father was an attorney, who tried to get his son to follow him into the law – but the young Smeaton persuaded him that such a course would not suit the ‘bent of his genius’. By the time he was eighteen he was a self-taught and proficient metal worker, who became interested in a whole range of scientific and technical subjects from instrument-making to astronomy. In 1753 he was elected to the Royal Society, and in 1759 he received the Society’s gold medal. His civil engineering career dated from 1755 when he was recommended by the Earl of Macclesfield, who was then President of the Royal Society, for the job of building a new Eddystone lighthouse after the old one had been burned down. From there he went on to a number of important civil engineering works: harbours, bridges and canals. For Smeaton, the work on canals was merely a part of a busy and varied professional career – a notable contrast to Brindley, who gave his canals all his time and enthusiasm. It is hardly surprising that the educated and urbane Smeaton had the self-confidence to stand up to Brindley, the acknowledged expert. The two men make a complete contrast in background and outlook: Brindley from a poor family, uneducated, devoted to canals; Smeaton from a wealthy family, with wide-ranging interests. They are the two extreme examples of canal engineer – most came somewhere in between.

John Smeaton. (National Portrait Gallery)

Just as the men who became engineers came from different backgrounds, so their entry into the engineering profession and their training and preparation for the position of chief engineer differed. At Brindley’s death, for example, a number of canal companies found themselves suddenly faced with the lack of a chief engineer, and men who had been surveyors or assistants suddenly found themselves promoted. As canal work became more common, men were able to get themselves taken on in junior posts, with the hope of learning the job as they went along and eventually finishing up in the chief engineer’s chair. There was virtually no theoretical training, and what there was was not considered to be of any great value to the practical engineer. Sir John Rennie described his own training and the views of his father, the canal engineer:

‘My father wisely determined that I should go through all the graduations, both practical and theoretical, which could not be done if I went to the University, as the practical parts, which he considered most important, must be abandoned; for he said, after a young man has been three or four years at the University of Oxford or Cambridge, he cannot, without much difficulty, turn himself to the practical part of civil engineering.’

Sir John Rennie, Autobiography, 1875

A view of university education not entirely unheard today.

By whatever route a man arrived at the job of chief engineer, the job itself should, in theory, have followed a well-established pattern. The chief engineer’s responsibility was for laying out the main line of the canal, designing its main engineering features, preparing the necessary plans and specifications, and handing those over to the men on the spot who would then get on with the job of building the canal. The chief engineer would then make occasional descents on the works, as though from some Olympian heights, to see how the work progressed and, if necessary, to issue fresh commandments. In practice, the chief engineer found that things seldom, if ever, went that smoothly.

The first problem that the canal engineer had to face was how to deal with the Committee. The engineer was the qualified expert whilst the Committee was composed of unqualified laymen – but the Committee were the employers, and the engineer, however grand, only the employee. William Chapman was one engineer who fell foul of his Committee. He became involved in an argument over who should have the responsibility of hiring the resident engineer – the chief engineer’s man-on-the-spot. Chapman argued that the decision was a matter of weighing up the applicants’ technical abilities, a job which he alone was competent to undertake. The Committee argued quite simply that they were the employers, and they would hire and fire exactly as they saw fit. The argument grew so heated that Chapman tried to bypass the Committee altogether, by appealing directly to the company’s shareholders for support. He wrote a pamphlet in which he stated his side of the argument, and quoted John Smeaton on the shortcomings of Committees in general: ‘the greatest difficulty is to keep committees from doing either too little or too much – too little when any case of difficulty starts, and too much when there are none.’1

Chapman had no great success in his attempt to go over the Committee’s head. Smeaton himself was just as forthright when it came to a Committee interfering in what he considered to be purely technical problems. He left them in no doubt as to how he viewed their different roles in the enterprise:

‘If, instead of making plans, I am to be employed in answering papers and queries, it will be impossible for me to get on with the business… All the favour I desire of the proprietors is, that if I am thought capable of the undertaking, I may go on with it coolly and quietly and whenever that to them shall appear doubtful, that I may have my dismission.’

Smeaton to the Forth and Clyde Committee, October 1768, in Reports of the late

John Smeaton, FRS, 1812

Smeaton had no worries in issuing a direct challenge, for he had many other sources of income. Others were not so fortunate. Most were aware that they were first in line for blame if things went wrong, and that they could be dismissed at any time. The wise engineer was careful to begin by establishing a good rapport between himself and the Committee. Usually he was successful.

The first part of the engineer’s work – the laying down of the line for the canal – was the part in which the individual stamp of an engineer can most clearly be seen. Brindley and the other early engineers aimed at the flattest, which in practice meant the longest and most devious, line. This was largely a matter of necessity. The technology of canal construction was in too rudimentary a stage of development to allow for any other course; the engineers, not knowing a great deal about how to go through or over a hill, or lacking the facilities to do so, went round it. Later engineers were able to take a more direct route – Samuel Smiles described the work on the Rochdale Canal, built between 1794 and 1804, though he wrongly ascribes to John Rennie an accomplishment that rightfully belongs to William Jessop:

‘In crossing the range at one place, a stupendous cutting, fifty feet deep, had to be blasted through hard rock. In other places, where it climbs along the face of the hill, it is overhung by precipices.

‘No more formidable difficulties, indeed, were encountered by George Stephenson, in constructing the railway passing by tunnel under the same range of hills, than were overcome by Mr Rennie in carrying out the works of this great canal undertaking.’

Samuel Smiles, op. cit., Vol.2, 1874

The personal preferences and technical abilities of the engineer would, in a perfect world, be sufficient for the determination of the best line for a canal to take. Unfortunately for the engineers the world was not that simple. Canals were not built across a deserted wasteland, and one of the first things that the engineer had to consider – or which, at any rate, the Committee would insist he had to consider – was the feelings of the more important of the local landowners. Sometimes the engineer would have to make a minor deviation: ‘frequently, when the canal passed in sight of any gentleman’s seat, [the engineers] have politely given it a breadth, or curvature, to improve the beauty of the prospect.’2 In other cases, the changes necessary to keep the peace with a really influential landowner could involve rather more than a polite curve. Discussion about the best line for the Oxford Canal, which had originally been surveyed by Brindley, went on after his death. His successor, Samuel Simcock, set out the arguments for allowing the canal virtually to circle the hill at Wormleighton – the shorter, direct route would, he said, be more expensive and rather difficult to cut. Then he got down to what sounds suspiciously like the real reason behind the decision: the short route would ‘be much more injurious to the Estate of Earl Spencer’, whereas, when he came to consider the long route, he was able to point out: ‘There is one pleasing circumstance in this part of the Navigation and that is, there will be no lock on the Canal thro’ the whole Lordship, the navigators will have no business to stop … so that the apprehended Danger from the inroads of the Bargemen will be the less upon that account.’3 The engineer was as aware as anyone else that the company had no desire to quarrel with Lord Spencer. The long route was taken without further argument.

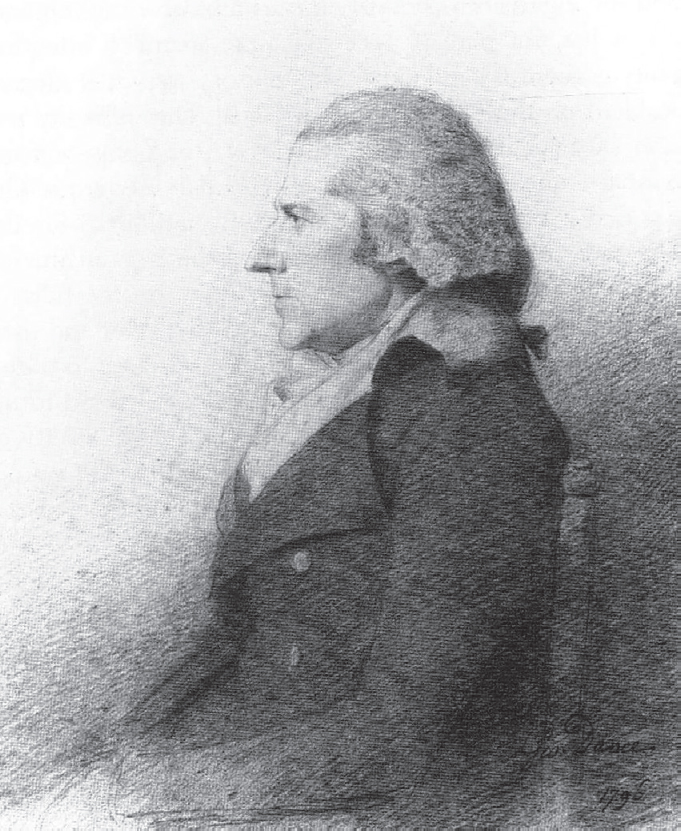

Even when it came to such matters as the design of an aqueduct, which could have reasonably been supposed to he entirely within the engineer’s province, local politics, the need to appease special interests, cash problems, all had to be taken into consideration. Some concessions were harmless enough. Sir Francis Shipworth was given permission to paint the aqueduct at Stretton to fit in with the view from his house (alas, there is no record of the colour scheme he chose). John Rennie, who was responsible for Britain’s finest masonry aqueducts, had his problems. When he was working for the Lancaster Canal Company, he found that the instructions he received about the bridges and aqueducts for the canal varied considerably. At times, the Committee were happy enough to indulge any whims and fancies, provided they were the whims of someone important: ‘Mr Cartwright was mentioning that you had expressed a wish to have an ornamental battlement placed on the Hale Bridge … the Committee will be very ready to give any directions of this kind which you may think will give pleasure to Lord Balcarray.’4 The Committee itself occasionally came in with a little advice on aesthetics:’ The flat cap on the top of the Pilaster at the Bulk Aqueduct will not have a good appearance. Could you not design something that will look more like a finished piece? The Work looks well and a little finish there would add to its beauty.’5 And when it came to Rennie’s masterpiece of canal engineering, the Lune Aqueduct, the Committee were prepared to defend any expenditure. Samuel Gregson, the Company secretary, wrote to Rennie:

‘I have had several letters of enquiry from Mr Horner … he had heard that a great deal of money had been wasted on our Masonry. I endeavoured to explain these false Jokes away and recommended him to wait upon you to examine the design of the Lune Aqueduct. Then he would be able to judge how far the Committee ought to be censored for expending £127! in ornamenting that great work.’

Lancaster Canal Company Letter Book, Letter from Gregson, 8 September 1800

John Rennie. (National Portrait Gallery)

Six months later there was a drastic drop in the company’s funds and Rennie found that the instructions received by himself and Jessop, who had been called in to help in the crisis, were of a rather different tone. They were asked to resurvey the Ribble valley. The original plan had called for an embankment, another fine masonry aqueduct and locks; now the Committee wanted to consider a plain, unadorned aqueduct, possibly of iron instead of stone, and, above all, they wanted to know ‘the best and cheapest mode of making a communication between Clayton Green & Preston, while an Aqued’ of some sort or other is carrying on’.6

An engineer’s life could be plagued by these social and financial pressures that reduced him to searching for compromises between the ideal construction; and that which politics and money would allow. From that point of view, the engineers working on the earliest canals were more fortunate, for their works were less often hit by financial difficulties. But they had to work with unskilled labour and inadequate tools, which imposed their own limitations. One of the features of the later period was the large amount of technical literature that appeared, together with reports of various inventions, such as dredgers, for easing the labour of canal construction. But, in spite of all the compromises, the canal engineers were still, quite often, able to build what they wanted in the way that they wanted. All the great engineers had their specialities.

John Rennie’s speciality was the aqueduct – the best of which, with their classical details, are among the eighteenth century’s most impressive monuments. One side of his ability that has not perhaps received quite so much attention is his mechanical ingenuity – there is a splendid example of a typically elegant Rennie solution to a problem on the Kennet & Avon Canal. The difficulty was the common one of water shortage. He decided to build two pumping stations, to pump water into the canal – one at Crofton and the second at Claverton. The Crofton pumping house used a conventional pair of steam engines to lift the water, but at Claverton he had a different idea. The pumping house was situated next to the River Avon, between the river and the canal higher up the hillside. Rennie’s scheme was delightfully simple: a stream was led off the river and used to turn a waterwheel; this was geared to a beam engine which was used to pump water up the hillside and into the canal. So the power of water was used to lift water – the next best thing to perpetual motion. It is a tribute to the quality of Rennie’s engineering, and to the craftsmanship of his workers, that the water-powered engine at Claverton was still regularly working in the middle of the twentieth century.

William Jessop’s speciality, if it could be called a speciality at all, was quietly, methodically and self-effacingly to organise a major canal project with the minimum of trouble to anyone else. He was many people’s idea of the ideal chief engineer. He was a calm, modest and immensely sensible man – an attitude reflected in his work. His great project, the Grand Junction, is singularly free of any dramatic flourishes – its great tunnels at Braunston and Blisworth have no heavily ornamented entrances, no imposing facades – everything is as sensible and workmanlike as the engineer himself. Apart from being modest about his successes, he was always ready to admit to his mistakes – the most serious of which involved aqueducts, which often seemed to have given Jessop trouble. Unfortunately this admirable and, among engineers of that time, rare quality, misled many into underestimating his ability. Mr Robert Mylne, an irate shareholder in the Gloucester & Berkeley Canal Company, wrote to the company’s secretary in 1802:7

‘Well, my Good Sir,

I had your 2 Summonses to attend general meetings of 29 Sept. & 12 Octr. – Is there nothing going forward with the Canal? Is it to lay Dorment in a deserted State for ever? – It always was in want of a Chancellor of the Exchequer, & a better Chairman – Till this time, I have not had leisure to reflect on the miserable and misguided State of it, and its lamentable fate – It is a work that requires other talent & knowledge than a common Canal Cutter – From the time of Jessop’s visit, I date its misfortunes. He and Dadford are mere drudges in that confined school; and both are without any sense of extended honour. The G. Junction is in a Dreadfull State, & required to have its difficult points all reconstructed. I have lately surveyed it. The Irish are advertising for a Resident Engineer. I think Dadford and they would fit one another to a T, for wrong heads and deficiency of knowledge.’

William Jessop. (National Portrait Gallery)

Mr Mylne may have been master of a fine vitriolic rhetoric, but he was considerably less than just in his criticism of both Jessop and Dadford. Jessop, far from being a drudge, was a man who learned from his own mistakes and took a deal of trouble to listen to the advice of others. Rennie described a meeting with him:

‘Since my last, Mr Jessop has been here and on conversing with him regarding the failure of the aqueduct over the River Darwin I find the lateral pressure of the water forced out the spandrill walls (which ultimately fell down) split the arch asunder longitudinally – this bridge has been repaired and they have adapted iron bars long and crossways same as I have drawn for the Lune … on showing him what I recommended in that way he said he so much approved of that mode he never would build an aqueduct of any magnitude without them.’

Letter to Gregson, 25 March 1795

Jessop was certainly willing to learn; if he had a fault, it was in his over-eagerness to don the hair shirt and take all the blame on to himself. Many of the troubles that beset him and all canal engineers came from the unavoidable gap between the instructions they issued and their execution, for they were seldom able to spend very much time overseeing the work themselves. Rennie stressed this point, whilst rather piously pointing out the superiority of his own methods over lesser engineers, particularly where they had had to skimp on materials:

‘I have hitherto made it a rule of my conduct to give such dimensions to works as to insure a certainty of success … many professional engineers have acted otherwise – hence the numerous failures that have lately happened in the various canal works &c throughout the kingdom … we have had no failure as yet, and trust while the plans are properly adhered to and the works well executed we shall have no occasion to be afraid.’

Letter to Gregson, 14 March 1795

Rare photographs of an Outram tramway in use. It carried coal from Denby, and horse-drawn trains ran on it until 1908. The top picture shows the iron rails on their stone sleepers: the lower shows the technique of ‘containerisation’ in use.

Jessop’s modesty led to his undervaluation by his contemporaries and, until recently, by posterity. Detailed work by Charles Hadfield and A.W. Skempton8 has shown that, apart from the canals on which he was chief engineer, he was adviser on many more. He was, it is now clear, the leading figure in canal engineering after Brindley’s death. In his biographers’ words: ‘Then came Jessop – alone – to tower over the period from 1785 to 1805.’

One engineer who became the complete specialist was Benjamin Outram. It became a common practice to build tramways, simple railways, between an industrial concern, such as a coal mine or iron works, and the nearest canal. When a tramway was being considered, Outram s name came up first. The usual tramway was made of rails laid on stone sleepers, on which carts could be pulled by a team of horses. Later, when so many canal companies were running out of funds, Outram found that his expertise was in even greater demand. It was very common for canals to be started from either end. When funds later ran out, the proprietors often found themselves with an embarrassing gap in the middle. One popular solution was to call in Outram to survey the canal and consider the feasibility of joining it together with a tramway. It is ironical that this solution, which seemed to offer salvation to hard-pressed canal proprietors, should prove to be the forerunner of their ruin – for it was on a tramway that Trevithick made his first successful experiments with a steam locomotive running on rails.

As well as planning and designing the canal, the chief engineer was expected to spend a certain amount of his time each year in inspecting the work in progress, reporting on what he found and attending general meetings of the company. This was all obviously necessary, but by the end of the century, when the mania was at its height, there was a huge increase in the numbers of canal projects – in the one year, 1793, authorisation was given for nineteen new canals to be built. It was easier to increase the numbers of canal projects than it was to increase the numbers of first-class engineers. Consequently, the men with big reputations found themselves constantly in demand – it was the Brindley’story all over again, but multiplied. Each Canal Committee, naturally enough, wanted its full share of its engineer’s time, and letters were sent continuously to keep him informed of progress, to ask advice and, with increasing frequency, to ask when he was coming to the works. As the Committee pursued the engineer with requests, the poor man himself was often trying to cope with a quite frighteningly hectic itinerary. When a letter from the Lancaster Committee finally caught up with him, Rennie wrote back on 13 November 1795 to explain why he had been such a long time in replying. He reported that he had just left Launceston in Cornwall, and had recently been at the Stourport and Birmingham canals, and had been to look at aqueducts on the Leominster Canal. He was, he said, at present at York, but had to return immediately to London. He hoped to be up in Lancaster early in the new year, but he did have first to attend at two general meetings on 5 and 8 January. Bearing in mind that he was travelling on atrocious roads, in the worst weather, often visiting remote workings that could only be reached on horseback – that adds up to a gruelling period of work.

The successful engineer had to work hard, and seldom had more than a minimum of staff to help with such work as surveying and drawing up plans. He was expected to involve himself in canal politics and canal finance. He even had to cope with the possibility of an early version of industrial espionage: a report was sent to the Oxford Canal Company, informing them of the activities of the engineers for the London & Birmingham Canal Company: ‘Mr Walker and Mr Thomas have been in the Field for a fortnight. Would it not be proper to employ a spy on their operations so that their parliamentary line may be known?’9

But if canal engineers were hard worked, they were also handsomely rewarded, gaining in terms of social status and hard cash. When Rennie debated the merits of a university education for his son, that in itself was a mark of the social progress that he had made. The engineer was able to move quite freely among, and associate on equal terms with, some of the best intellects of the age. He might not be equally at home in the fashionable and aristocratic world of London and Bath, but among the growing and increasingly influential groups of scientists, technologists and industrialists he more than held his own. When a portrait was painted of the most influential of these men, the canal engineers were fully represented.

The financial rewards for the successful engineer could be enormous. A man such as Jessop not only had his fees but was also a shareholder in various canal concerns and had shares in other industries as well. He had, for example, a considerable holding in a Derbyshire mining concern. Benjamin Outram’s profits came as much from the Butterley Ironworks, in which he had a partnership with Jessop, as they did from tramway construction. John Rennie’s account books covering the years 1794 to 1800 show an enormous increase in his income from approximately £7,000 per annum to £16,000. Out of this money he had, of course, to pay expenses, which were considerable, and salaries to his staff. Even so, the extent of his wealth can be judged by an entry for 1800, which showed that he paid out £11 for Christmas boxes. To earn £11, an ordinary canal labourer at that time would have had to work for six months. Brindley made a fortune but killed himself in getting it – later engineers were able to retire to live the lives of gentlemen.

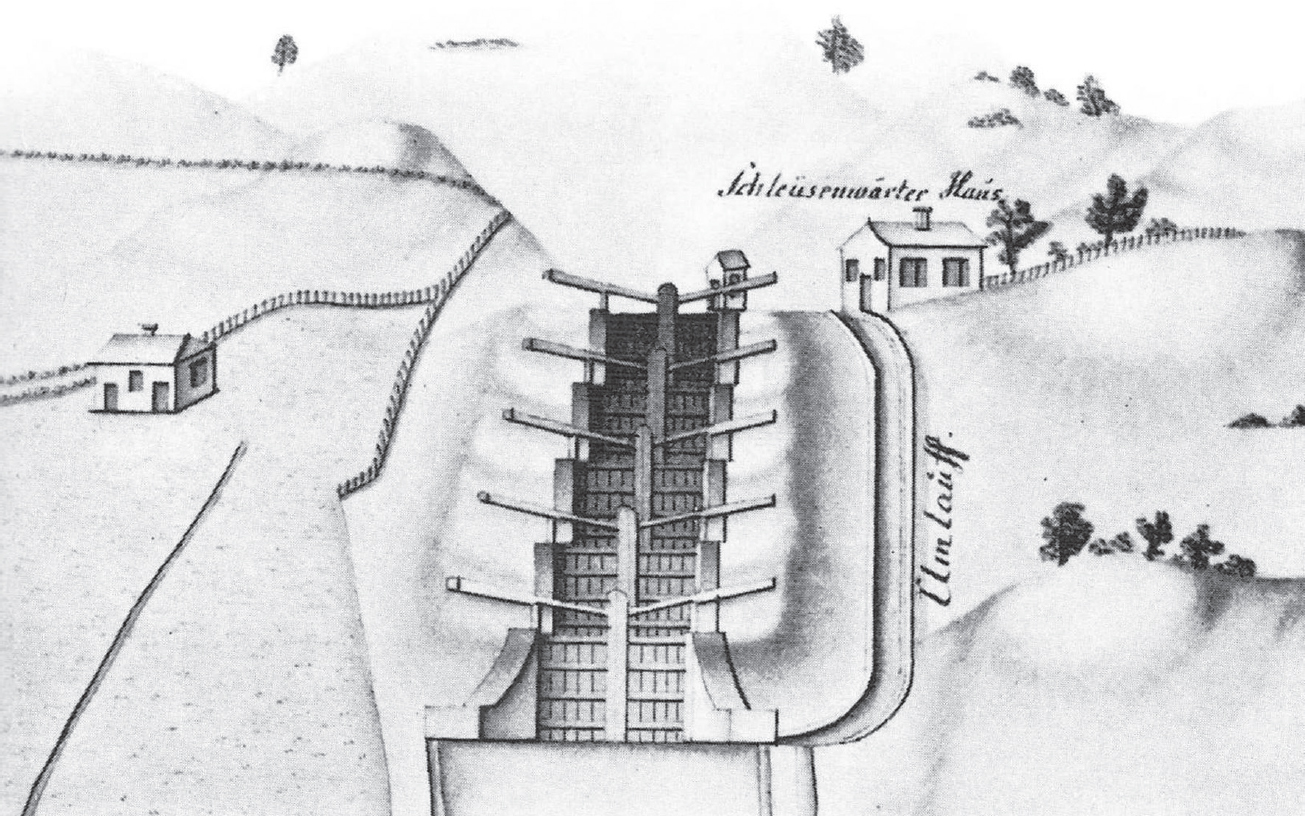

But not all engineers were Rennies or Jessops. Some gave all their time to one project and faced retirement in rather different circumstances. The engineer during the early years of work on the Leeds & Liverpool Canal had been Mr Longbottom. He left the works when they temporarily closed during the depression years, and never returned to his old job. On 6 June 1800, he wrote to his former employers:

‘Gentlemen Your Petitioner humbly presumes to lay before this General Meeting of the proprietors of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal such circumstances as he hopes will dispose them to take his case into consideration and to grant the object of his prayer.

Your Petitioner begs leave to remind this Company that he was for five years their Servant and Engineer. That during his Service he laboured with indefatigable Industry and exerted all his Abilities to promote the Interest of the Proprietors and he hopes he may say that when it is considered that in less than five years he compleated upwards of sixty Miles of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal for little more than one hundred and sixty thousand pounds his Abilities and Attention will not be called in question.

That since he was obliged to leave their service he has never been inattentive to their interest. He hopes he may state that the Proposals he has from time to time made to this Company of Particulars which he apprehended might be advantageous in completing the work will fully justify this sentiment …

Your Petitioner begs leave further to state that in the decline of life, without Employment his Means of Subsistence are extremely slender; that tho’ his Exertions thro’ Age are not equally vigorous as in youth yet he trusts they may still be useful to this company and therefore he humbly prays.

That this Company will have the Goodness to allow him a small annual stipend and he will very cheerfully be at the Command of this Company in any Services to which they may think proper to call him.’

Leeds & Liverpool Canal Committee Book

A rather curious view of the Bingley Five Rise on the Leeds & Liverpool Canal. The engineer, John Longbottom, ended his life in poverty. (British Museum)

The Committee agreed to see if there was not something that could be done for Mr Longbottom. It was the following spring before anyone got round to seeing the old man. He had died during the winter. This was the man who designed what is now known as ‘One of the Wonders of the Waterways’ – the Bingley Five Rise. Historians tend to dwell on the successful and famous. There were others.