Administration

This has been a day of complaints and I am heartily tired of them.

Samuel Gregson, secretary to the Lancaster Canal Company, in a letter to

Archibald Millar, 9 April 1796

Samuel Gregson was to the administration of the Lancaster Canal what Archibald Millar was to the engineering, and, on reading through his correspondence, one gets the impression that every day was a ‘day of complaints’. He was the canal company’s professional worrier. During the period of canal construction, anyone who felt he had any sort of grievance against the company or against one of the company’s employees went, as a matter of course, to the representative of the canal Committee – the gentleman usually known as the secretary or as the Chief Clerk or Clerk Accountant. To simplify matters we shall call him just ‘the secretary’.

In theory, the organisation and administration of the canal was the responsibility of the elected Committee; in practice, the day-to-day handling of affairs was left in the hands of the secretary and his staff. The Committee took the major decisions, but relied on the expert advice of their engineers – or, to be more accurate, if they were sensible they relied on the expert advice of the engineer. The implementation of those decisions was the secretary’s responsibility, and he was left to get on with it. The Committee were, after all, part-time amateur administrators, and canal constructors had their own careers to attend to and their own affairs to manage. While they might be tempted to meddle in the glamorous activities of the engineer, they were unlikely to feel any great envy for the life of the administrator or feel any compulsion to take over such jobs as letter-writing, price negotiating, or pacifying angry farmers.

We know even less about the canal administrators as individuals than we do about the engineers, though, as they conducted so much of the company’s business, we do know quite a lot about their actual work. But it is possible to get at least an inkling of the sort of man that would be chosen as an administrator. The emphasis was first on respectability – the secretary was the company’s public face and it was considered essential that the face should be a respectable one. A great deal of emphasis was placed on sobriety.1 And, having got a suitably sober and respectable employee, the company would take steps to try to ensure that he stayed that way. The Huddersfield Canal Company had a rule, for example, that ‘no person who shall be employed as Book-keeper or overseer for the said Company shall be allowed to keep a publick House or to sale any victuals, or cloathing, to the workmen employed in or about the works of the said Canal.’2 It is not difficult to see why such a rule should be necessary, for the possibilities of corruption would otherwise have been enormous. There certainly was bribery and corruption among canal workers at all levels,3 though it is difficult to estimate just how much went on – by its nature, it was a secretive business and unlikely to find its way into the official records. But certainly some companies did operate a ‘truck’ system of payment, with all the abuses that that system almost inevitably entailed.

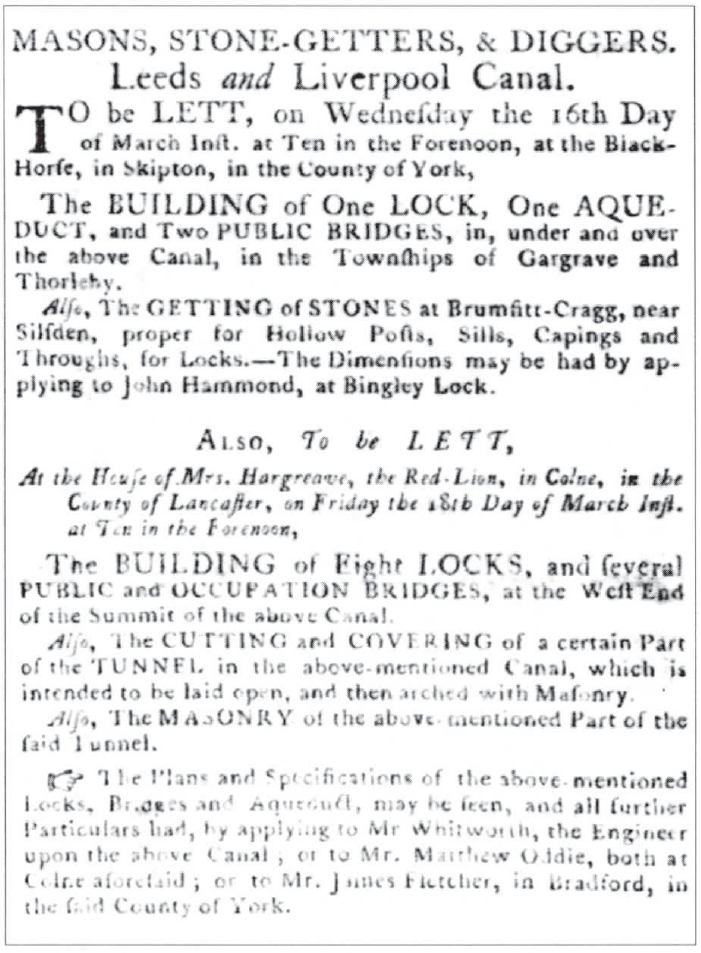

The first job of the administration was to advertise for contractors to undertake the work: this advert is from the Leeds Intelligencer. (British Museum)

The Committee and the staff needed permanent accommodation. An entry in the Warwick & Birmingham Minute Book suggests that their offices were rather more pleasant than the accommodation provided for Mr Exley at the Lune works. They rented a house and set out a list of the alterations that would have to be made to turn it into a properly appointed canal company office:

‘To put a skirting Board round the Room appointed to the use of the Committee and to put an Hearth stone and Chimney piece to the same.

To build a Brewhouse, Privy and Wall, to make the yard and Garden private and entire – To sink a well and put down a pump – to glaze the windows in the room to be occupied as an office.’

Warwick & Birmingham Canal Minute Book, 8 July 1793

The ‘brewhouse’ was not a standard item of company office equipment. However, having appointed a suitably respectable secretary and having provided him with an office and a suitably sober staff to man it, the Committee were then able to delegate a great deal of the company’s work. Some of the different aspects of the secretary’s job were similar to those of the resident engineer.4 Both men would be involved, for example, in land purchase; both would be expected to do their bit in bringing difficult contractors to heel, and both would be involved in work measurement. The first job which the secretary would tackle, and which was particularly his own, was that of agreeing terms with the contractors before work started. But here, too, he would seek the engineer’s advice – particularly the chief engineer’s, as he would be able to give an idea of the going rate in different parts of the country. Settling the rate for the job was a long and complicated matter. There were many different factors to be taken into consideration – what type of country was the canal passing through, were materials to be supplied by the company or by the contractor, how complicated was the work, would there be any side benefits for the contractor, and so on. Faced with so many variables, it was obviously easier to let out work in big lots and save on the paperwork; hence the deaf ear which greeted the engineers’ requests for smaller lots to be issued.

Once the contractors were in, the secretary and his staff were responsible for bookkeeping – which often turned out to be a somewhat livelier occupation than one would expect. The large contractors had their own book-keepers, and the two rival clerical forces came up with some very different sets of figures. The Lancaster Committee’s books, at one point, showed one set of contractors as having been overpaid by £180, while the contractors’ own books came out with a balance of £8,000 owing to themselves. The Lancaster Company finally agreed to pay over an extra £1,500 to avoid work coming to a halt.5

Money was a major preoccupation of almost everyone concerned with canal construction, and the major part of the worrying fell to the secretary. It was his responsibility to ‘call’ on the subscribers to provide the extra funds which their shares in the company specified that they should provide. When a call failed, it was then the secretary’s job to wheedle or threaten the non-payer until the funds were forthcoming. While he was trying, often with little success, to get the money from the shareholders, the secretary was also being pressed for money for the works – the engineers needed money to buy essential materials and supplies, the contractors needed money to meet their wage bills. As Archibald Millar, the engineer, remarked of the secretary, no doubt accurately: ‘Wood, iron’ Coals and Money will give Mr Gregson the Dry Belly Ake.’ The dry belly ache was an occupational hazard of hard-pressed secretaries. As the work progressed on the canal, their financial problems grew, and another aspect of finance appeared to occupy the secretary’s time – the company’s income.

The canal engineer worked on a project until the canal was completed and then moved on – the secretary, on the other hand, had a permanent post. When the construction period was ended, he still had the responsibility of looking after the returns from the tolls and traffic of the canal. This was a simple and straightforward arrangement, but, unfortunately for the hard-pressed secretary, the two periods usually overlapped, sometimes by many years. It was quite common, when a sufficient length of canal was navigable, for it to be opened to traffic. This provided the company with a double benefit: there was revenue from tolls and cheaper transport for the company’s own supplies. The former might be quite a small sum at first, but the savings on transport costs could be considerable:

‘The Coals by the Canal are sold here at 10d p Hund Weight. They cost us before (& do now, if they do not come by the Canal) about 13½d Hund Weight – So you see that we have already a considerable saving as Housekeepers. I have no doubt if we get fairly to work this Concern will do well, but it never will answer the desired purpose either to the publick or to the proprietors until we get over Ribble & communicate with the Coal Country.

Lancaster Canal Letter Book, Gregson to Rennie, 4 March 1798

Secretaries were always trying to find more money, but the situation became much easier once a section was in water and trade had started. This very heavily-laden boat is on the Coventry Canal. (Miss M.E.Waine)

This was all a great help to a company very short of money, but it all meant extra work for the secretary.

The secretary was liable to be involved in any and all canal activities. He spent as much time as the engineer in trying to control errant contractors. He had no direct authority over them, but he did have one weapon – money. As the representative of the Committee, he was able, if necessary, to withhold payment. It was a delicate problem, for he had to balance the possible gains of forcing the contractor to improve the quality of his work, with the possible losses if the contractor decided to retaliate by stopping work altogether. The secretary usually found that his threats were not particularly convincing. This was partly because so many companies began with a fine flurry of optimism, and quite cheerfully paid out advances to the contractors. When the secretary then began to make threatening noises, he would often discover that his threat was meaningless as the contractors were already overpaid. Accountancy, at that time, could not be described as an exact science. Samuel Gregson, in his long fight with the contractors Pinkerton and Murray, was reduced eventually to writing a despairing letter to Rennie to ask him to ‘devise some method either by fair means or compulsion which will enable us to get on’.6 Neither engineer nor secretary was able to find the perfect solution.

Although the secretary was supposedly concerned with the overall pattern of administration, his work constantly involved him in the minutiae of canal work – every problem seemed to end up on his desk. The Committee of the Coventry Canal Company passed over to their secretary the task of handling problems of theft from the workings and ordered him to ‘take the necessary measure for the prosecution of Francis Woodhouse charged by Mr Robinson with having stolen part of a plank’.7 (There is, unfortunately, no indication of how a man could steal part of a plank.) On the same day, he was ordered, without any reason being given, to sack part of the workforce.

The main problem, and the main source of complaints, came from outside the company. With hundreds of men spread over miles of previously peaceful and undisturbed countryside, it was only to be expected that there would be problems. The local dignitaries, the tenants, the landowners, the farmers, the mill-owners, all found their way to the canal office to tell their woes to the secretary. He had the double job of passing on the complaints to the engineers or the contractors, with suggestions for avoiding repetitions, and of pacifying the complainants. Pacification usually came in the form of cash – yet another drain on resources – and, where agreement could not be reached privately, a further expenditure of time and money had to go into taking the affair to arbitration. Arbitration was not popular with either side, as the loser would normally have to pay the costs for both parties. It was a gamble, and some cases that came up seem hardly to have warranted taking the chance. In March 1799, for example, a case was taken to the Commissioners for the Montgomeryshire Canal. Richard Pryce was complaining about loss of water to his mill. The company offered compensation of £19 12s, which the Commissioners eventually decided was fair: Pryce was then faced with having to pay the whole of the costs, which reduced his compensation by £7 1s 4d, almost half. It seems a great waste of time and effort. As a rule, the company was reasonable about compensation – in the long run it was easier and probably cheaper. The only case recorded by the Montgomeryshire Commissioners where the final figure was at wide variance with the original offer came in 1814: compensation of £83.62 was awarded against an original offer by the company of £21.75. An expensive day for the company, who also had to pay the costs.8 In general, both sides preferred to settle privately. Another role which the versatile secretary was expected to play was that of personnel manager. Staff problems came in two main categories: complaints about the staff and workers, and complaints by the staff. The former were the more frequent, and most frequent of all were the ones referring to drunkenness and riotous behaviour. If the complaint referred to the workmen, then it was generally accepted as true without further investigation (but usually with justification) and the standard reprimand was sent. It was regarded as an inevitable fact of life that workmen would get drunk. But if complaints referred to a member of either the office staff or the engineering staff, then that was a very different matter. There was no immediate acceptance of the accuracy of the complaint here: ‘Whereas several Reports have been Spread reflecting on the character & conduct of the Officers of this Company, ordered that no regard be had to such Reports unless the same are reduced into Writing.’9 But if the complaint was found to be justified, then the unfortunate ‘Officer’ would find the treatment he received rather different from that handed out to the Lune engine-man after his four-day binge. The man not only got the sack, he got a sermon to go with it:

‘Complaint having been made to the Canal Come of some bad and disorderly conduct in you on Saturday Evening last and being apprehensive that this is not the first … they have given me the disagreeable cross of discharging you from their Service … to keep you longer in their employ would only give you an Opportunity to lead others astray who perhaps influenced by your Example might become bad Servants to the company as well as bad members of Society.

I hope this business will be an example to yourself as well as to all other Agents of the company who may rest assured that no Encouragement whatever will be given to them where there are any Appearances of vice. But wherever sobriety and Strict Attention to the duty required from them is found in any Agent, the Committee will never lose sight of the Man, and his preferment will follow in proportion as he makes himself more useful to the Concern.’

Lancaster Canal Letter Book. Letter from Gregson to William Porteus, 5 May 1795

Complaints from the staff were, occasionally, departmental disputes which the secretary was expected to sort out; more commonly, they referred to the popular preoccupation – money. Confronted by a request for extra pay, the secretary’s attitude has all the hallmarks of his Victorian successor, combining, in equal proportions, paternalism, morality and economics. Here is Samuel Gregson writing to the young superintendent of cutting, Thomas Fletcher:

‘It is certainly the intention of the Committee to give you every reasonable Encouragement it you stay in their Employ. But if by Encouragement you mean an immediate advance in your Salary they give the answer as before (viz.) that an advance cannot be agreed to. If I might advise you as a friend, I would say that your future reputation and establishment as a professional man is of more consequence to you than an advance of Salary at present, you are yet very young and have much to learn. If you continue in a work like ours your abilities must improve and it will be much more to your credit to say you have stayd during the completion of a great work than to say you were present during the execution of some parts.’

Lancaster Canal Letter Book, 12 August 1796

The secretary’s job was far from being that of a desk-bound office man – he probably spent almost as much time travelling around the workings as the engineering staff did. Samuel Gregson’s letters give a picture of all these varied activities – inspecting and measuring work with the engineer, going to see landowners, setting payments, all interspersed with a few notes about falling off his horse or being confined to his bed with the rheumatics: by no means an easy life, but certainly a varied one. As a result of all these different activities, the secretary gained quite a reasonable working knowledge of engineering practice, which it was always possible he might be called upon to put to use.

The Warwick & Birmingham Company had troubles with their engineers and, like most other companies in the late 1790s, with money. At the end of 1795, the aqueduct over the River Blyth collapsed and the engineer was dismissed. A year later they were still having problems – the engineering works were in a bad way, and they were too short of money to employ a really competent man, even if one was to be had. It was suggested that the works be handed over to a sub-committee but, as the Committee recorded, although it was an attractive proposition, they would ‘find it extremely difficult to select any Gentlemen interested in the Canal who are willing and at leisure to give up a part of their time in such an Employment and are capable of forming an accurate Judgement upon the various Works.’10 By the spring of 1798, however, it finally dawned on them that their clerk-accountant, P.H.Witton, probably knew as much about the business as most people, and decided that an admirable solution to all their problems would be to add the post of engineer to his existing duties – an answer which said more about the Committee’s preoccupation with economics than their common sense. So, for the moderate salary of £250 per annum, Witton became clerk, accountant and engineer. It was only a month before the inevitable entry appeared in the minute book:

‘P.H.W. having stated to this Committee that the business he is engaged is more than he is capable of executing without an assistant in the outdoor business.

Resolved that John Hughes be continued as assistant to Mr Witton.’

Warwick & Birmingham Canal Minute Book, 22 May 1798

As a rule, however, the secretary stayed in his own domain, and left the engineering to the engineers.

Witton’s salary of £250 for his combination of jobs reflects the average salary of secretaries rather than that of engineers. In general, they were on a considerably lower pay scale. Samuel Gregson’s salary was also £250 per annum with expenses of 10s 6d a day for ‘horse hire and expenses when travelling on the business of the Committee’.11 This is the same as the salary received by the resident engineer’s principal assistant, although the secretary’s responsibilities are closer to those of the resident engineer himself. But the secretary had one advantage – security. Once the canal was completed, the engineering staff had to look for new jobs, but the secretary stayed where he was. He could look forward to a period of comparative calm and, hopefully, rising wealth as the expensive construction period came to an end and the revenue at last began to roll in.

In general the secretary’s main attribute was versatility – there was very little that went on in the canal business in which he could not expect, at some time or other, to find himself involved. The other members of the administrative staff had calmer and less varied lives. The company’s solicitor, unless he was involved in the nerve-tearing business of Parliamentary work, would perform the usual legalistic functions – drawing up contracts, giving advice on the many disputes that arose between the company and others, and so on. The junior accountants and clerks had their own, rather dull, jobs to attend to. The only excitement which could be expected to come their way would come on pay-days, when they would take the money to the contractors. It was not so much the fear of robbery that caused the excitement, though wage robberies were by no means unknown, as the situation that could and did arise when they had to face a crowd of navvies and explain exactly why there would be delays in the payment of wages. The reaction of the navvies in those circumstances was all too predictable.